Abstract

Female mate rejection acts as a major selective force within species, and can serve as a reproductive barrier between species. In spite of its critical role in fitness and reproduction, surprisingly little is known about the genetic or neural basis of variation in female mate choice. Here, we identify fruitless as a gene affecting female receptivity within Drosophila melanogaster, as well as female Drosophila simulans rejection of male D. melanogaster. Of the multiple transcripts this gene produces, by far the most widely studied is the sex-specifically spliced transcript involved in the sex determination pathway. However, we find that female rejection behaviour is affected by a non-sex-specifically spliced fruitless transcript. This is the first implication of fruitless in female behaviour, and the first behavioural role identified for a fruitless non-sex-specifically spliced transcript. We found that this locus does not influence preferences via a single sensory modality, examining courtship song, antennal pheromone perception, or perception of substrate vibrations, and we conclude that fruitless influences mate choice via the integration of multiple signals or through another sensory modality.

Keywords: speciation, behavioural isolation, prezygotic isolation, fruitless, Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila simulans

1. Introduction

Female mate choice can impact both sexual selection within species and reproductive isolation between species. Females typically have a greater investment than males in reproduction resulting from a single mating [1–3], and thus benefit from fewer but higher-quality matings, which they achieve by displaying mate discrimination [4–6]. Female discrimination can select for higher-quality males within a species, and allow females to avoid maladaptive matings with males from other species. Since behavioural isolation due to mate choice divergence is likely to be the earliest factor to arise in the speciation process [7], these female preferences can contribute to the divergence and maintenance of species separation [8,9]. While a small number of loci have been identified as candidate genes for naturally-occurring variation in female preference behaviour both within [10–14] and between species [15–19], very few loci affecting female mating behaviour have been confirmed.

The Drosophila genus has multiple closely related species that are sexually isolated, making it a commonly used model for studying behavioural isolation [14,20]. Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans are two species that are behaviourally isolated: while D. melanogaster females mate at high frequencies with D. melanogaster males, D. simulans females do not [21,22]. However, hybrid females from the permissive cross between D. melanogaster females and D. simulans males [23,24] will mate with D. melanogaster males [25]. The receptivity of hybrid females towards D. melanogaster males therefore resembles D. melanogaster female behaviour, which suggests that D. melanogaster loci affecting female receptivity are likely to be dominant, or semi-dominant, over the corresponding D. simulans non-receptive loci. These D. simulans recessive loci are probably responsible for the rejection of D. melanogaster males.

D. melanogaster and D. simulans do not produce fertile hybrid offspring [23,26]. As a consequence, recombination mapping is not possible between these two species. Therefore, in a previous study we used deficiency mapping to identify small regions of the 3rd chromosome that influence species-specific female preference [19]. This uses pre-existing D. melanogaster lines that are missing a small portion of their genome (a deficiency); F1 inter-species hybrids produced from these lines contain one full set of both parents' genomes, with the exception of the deficient region, where only D. simulans genome is present (figure 1a). A key aspect of this assay is that it is not testing the effect of disrupting a gene's function, since the non-disrupted allele is functional. Instead, it is assessing naturally-occurring variation in the allele that is unmasked [28]. If hybrid females bearing a deficiency behave more like D. simulans females by rejecting D. melanogaster males rather than mating with them, the deficient region was further fine-mapped using smaller deficient regions. Here, we used this approach to identify a locus affecting inter-species female rejection behaviour: fruitless.

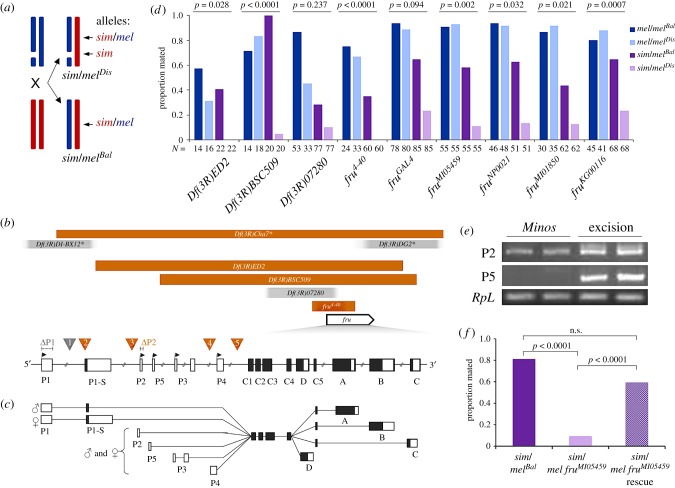

Figure 1.

Genetic mapping identifies the fruitless gene as influencing female rejection of heterospecific males. (a) Schematic of the 3rd chromosomes (blue and red lines) in deficiency complementation mapping. D. melanogaster (mel, top left) females bearing a deficiency or disruption (broken blue line) are crossed to D. simulans (sim, bottom left; red lines) produce hybrids inheriting intact chromosomes from both species (bottom right; sim/melBal) and hybrids inheriting a disruption in the D. melanogaster chromosome (top right; sim/melDis). Gene(s) within this disrupted region are only expressed from the sim homologue's alleles. (b) Genetic constructs used to assay female rejection of heterospecific males. Rectangular bars represent deficiencies; blurred ends represent imprecisely known breakpoints; scale is approximate. The three deficiencies at top (marked with asterisk) are from [19]. Orange is statistically significant (p < 0.05); grey is not statistically significant. Arrowed box represents location and direction of fru gene compared with the deficiencies; note that image is shown in orientation relative to fru. At bottom, fru is expanded and shown 5′–3′ to represent the fru P1–P5 first exons, common exons C1–C5, and 3′ exons A–D; boxes are exons, black boxes are coding. The relative locations of transposable element insertions are represented by numbered inverted triangles: 1 = fruGAL4, 2 = fruMI05459, 3 = fruNP0021, 4 = fruMI01850, 5 = fruKG00116; dashed lines represent targeted fruΔP1 and fruΔP2 deletion locations. Image not to scale. (c) Representation of fru transcripts. Adapted from [27]. (d) Proportion mated when paired with D. melanogaster males for control pure species females (1 h assay) without a disruption (mel/melBal), with a disruption (mel/melDis), and hybrid females (24 h assay) without a disruption (sim/melBal), when compared with hybrid females with a disruption (sim/melDis). Comparisons where sim/melDis females have a significant reduction in mating have p-values shown in bold. (e) Transcript presence in flies homozygous for the Minos insertion fruMI05459 compared with flies that have had the Minos element excised. The housekeeping gene RpL32 is used as a control. Each sample was done with a biological replicate. (f) Female receptivity is rescued when the Minos element within fruMI05459 is removed (n = 32). (Online version in colour.)

The frutless (fru) gene is best known for its role in sex determination. It has a highly conserved genetic sequence across the orders Diptera [29], Hymenoptera [30] and Blattaria [31], suggesting an ancient origin and a common function among different insects [32]. In D. melanogaster, the fru gene encodes a set of transcription factors generated via alternative exons at both the 5′ and 3′ ends (figure 1c) [33–36]. Transcripts begin with one of five first exons (P1–P5), followed by a central common region shared by all transcripts that contains a BTB (protein–protein interaction) domain, and ending with one of four final exons (A–D), three of which (A–C) contain a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain [37,38]. The function of fru has been primarily studied in relation to the P1 transcript group's role in generating male courtship behaviour [35,39–41]. P1 transcripts are sex-specifically spliced at the P1-S exon by the products of the transformer and transformer-2 genes to produce male- (fruM) and female- (fruF) specific transcripts (figure 1c) [37]. fruF transcripts are not translated into functional proteins, but are detectable in the central nervous system of wild-type females [38]. FruM proteins translated from fruM are expressed in approximately 3% of the neurons in the central nervous system [34,42] as well as the peripheral nervous system [37,43]. fruM behavioural phenotypes are specified by either a single, or combination, of isoforms [44,45], and FruM proteins overwhelmingly target genes involved in nervous system development [45].

The well-studied P1 transcript does not produce a functional protein in females and appears to not have a role in female mating behaviour [35]. While far less studied than the P1 transcripts, a subset of the non-sex-specifically spliced transcripts (P2–P5) are necessary for adult viability and external morphology [30,46,47]. The P2 transcript is most strongly expressed in the eye, while the P3 and P4 transcripts are expressed widely throughout development [36,48]. None of these other transcripts have been assayed for their effect on female behaviour. We show here that one of these non-sex-specifically spliced transcripts affects both intra- and inter-species female rejection behaviour.

2. Material and methods

(a). Drosophila strains and crosses

Flies were maintained on standard food medium (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) under a 14 : 10 light : dark cycle at 24°C and approximately 80% relative humidity. All Drosophila melanogaster disruption stocks are listed in electronic supplementary material, table S1. Deficiencies and gene disruptions were maintained over 3rd chromosome balancers (Bal) TM3 or TM6C. Unless otherwise noted, all stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, Indiana), as were line #3703 (w1118/Dp(1;Y)y+; CyO/nub1 b1 snaSco lt1 stw3; MKRS/TM6B, Tb1), frusat15 (Df(3R)frusat15/TM6B, Tb1), and the Minos transposase stock (w1118; snaSco/SM6a, P{hsILMiT}2.4). The fruGAL4 and fru4-40 lines were provided by Dr Barbara Taylor. The D. melanogaster stock with GFP-tagged sperm (w; P{w8, ProtA-EGFP, w+}19B(3)) was provided by Dr John Belote. The D. melanogaster fruΔP1 and fruΔP2 were made and provided by Dr Megan C. Neville at the Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, University of Oxford. Wild-type D. melanogaster BJS is an isofemale line collected by Dr Brent Sinclair. Wild-type D. simulans Florida City (FC) was provided by Dr Jerry Coyne (collected from Florida City, Florida; Coyne 1989); wild-type D. simulans 199 (stock # 14021-0251.199; Nanyuki, Kenya) and wild-type D. simulans 216 (stock # 14021-0251.216; Winters, California) were obtained from the Drosophila Species Stock Center (San Diego, California).

(b). Mating assays

Five to six Virgin D. melanogaster females bearing a disruption over a balancer (melDis/melBal) aged 5–7 days were crossed with 25–30 D. simulans FC or 3–4 D. melanogaster BJS non-virgin 5–10-day-old males to produce F1 hybrid sim/melDis and sim/melBal or mel/melDis and mel/melBal offspring, respectively. Assays were conducted as two replicates, whereby the flies used in assays were generated via two independent sets of crosses at slightly separate time points.

Virgin 5–7-day-old F1 females of the four genotypes produced above were paired with a 5–7-day-old virgin D. melanogaster GFP-sperm male in a no-choice mating assay. Assays were carried out at 24°C, approximately 50% relative humidity, and 1–2 h of ‘lights on’ in 30 ml plastic vials containing approximately 5 ml of standard food medium. All four genotypes (sim/melDis, sim/melBal, mel/melDis and mel/melBal) were assayed in equal numbers within any given assay to account for uncontrolled environmental effects that could influence mating activity (e.g. [49]). Flies were observed for 1 hour (‘1 h mating assay’) and scored for latency to courtship and latency to copulation. From these measures, the proportion that copulated out of those that were courted was calculated for pure species females. Assays involving F1 hybrid sim/melDis and sim/melBal females were left within the vials for an additional 24 h (‘24 h mating assay’), at which time the female was decapitated, her reproductive tract dissected and imaged with fluorescent microscopy, and scored for the presence or absence of fluorescently-labelled sperm. Hybrid females were scored as if all females were courted in the 24 h period. We compared the amount of copulation out of those that were courted in a 1 h assay for pure species females and the total proportion that copulated in a 24 assay for hybrid females. This comparison at different time scales was necessary due to the far lower level of receptivity of hybrid females towards these males. We found no difference in the occurrence of courtship for disruption versus intact hybrid females for all assays (electronic supplementary material, table S1; p > 0.05). The proportion that copulated was compared using logistic regression (α < 0.05) with the independent variables of species (mel/mel or sim/mel) and genotype (Dis or Bal) and the dependent variable of whether copulation occurred after courtship (yes or no). We considered a result biologically significant only if the sim/melDis females had reduced copulation compared with sim/melBal. Data were checked for overdispersion by comparing the null and residual deviances; no overdispersion was present. Analyses were done using R version 3.6.1 [46].

To test whether the reduction in receptivity due to fru occurs across D. simulans or is specific to strain FC, we repeated the above assays for fruMI01850 melDis/melBal crossed to D. simulans stock 199 and D. simulans stock 216, and analysed as above.

To test whether these females experience a general disruption in female receptivity, we paired fru4-40, fruGAL4 and fruKG00116 sim/melDis and sim/melBal females in no-choice mating assays as above, but using D. simulans FC males instead of D. melanogaster males, scoring for the presence or absence of sperm using a compound microscope. The proportion of females containing sperm for sim/melDis was compared with those for sim/melBal using a two-proportion Z-test (α < 0.05).

To test whether homozygous deletions induce changes in female receptivity in within-species assays, we paired homozygous fruΔP1 and fruΔP2 D. melanogaster females with D. melanogaster males in 1 h no choice mating assays and scored for courtship and copulation. Canton-S melanogaster females were used as a control.

To test whether females bearing a targeted deletion of the first exon of fru P2 (fruΔP2, see below) display active courtship rejection behaviours versus are passively non-receptive, we placed virgin F1 hybrid fruΔP2 females aged 5–7 days in single pairs with 5-day-old virgin D. melanogaster GFP-sperm males in a 10 min no-choice mating assay. We scored males for courtship latency, time spent actively courting, and number of copulation attempts, and scored females for number of ovipositor extrusions, times kicking, times displaying wing scissoring, and total time spent walking away from the male after he approached.

(c). RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from two biological replicates, each with 20 pure species or homozygous disruption 5–7-day-old females, using the TRIzol plus Purelink RNA purification kit (Thermofisher Cat# A33254). The fruMI05459 line is homozygous lethal, so was crossed with stock #3703 to create the genotype y1 w*; fruMI05459/TM6B, Tb1. Adult females were dissected out of late stage non-Tb1 pupal cases [33], which are homozygous for the disruption. RNA was quantified using a Nanophotometer P300 (Implen, Inc.) and 2 µg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with DsDNAase (Thermofisher, Cat# K1671) using oligo dTs. Two technical replicate were done for each biological replicate. RT-PCR was performed using a forward primer within each of the respective exons and a reverse primer within the common region of fru (electronic supplementary material, table S2). RpL32 was used as a control (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

(d). Excision of MiMIC insertion

The Minos mediated Integration Cassette (MiMIC) in fruMI05459 was excised by crossing to a Minos transposase stock using standard protocols [47,50]. Resulting males were screened for the excision of the MiMIC insertion by PCR genotyping using primers flanking the MiMIC insertion site (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Offspring produced from individuals with excisions were crossed together to create a stable stock with genotype y1 w*; [excised: Mi{MIC y+}fruMI05459]. The excisions were confirmed by sequencing the region flanking the MiMIC insertion site (electronic supplementary material table S2 and figure S2).

Five to six virgin females from the clean excision stock and virgin females from the original fruMI05459 Minos disruption stock were separately crossed with 25–30 non-virgin 5–10-day-old D. simulans FC males to create F1 hybrid sim/melDis+, sim/melDis, and sim/melBal females, where Dis+ indicates the excised Minos disruption. F1 hybrid females were aged 5–7 days and then paired separately with 5–7-day-old virgin D. melanogaster GFP-sperm males in 24 h no choice mating assays, as above.

(e). fruitless mutant lethality analysis

To test whether the MiMIC insertion in fruMI05459 disrupts P3 and P4 transcripts, we made ten separate crosses of 3 frusat15 males with 5 fruMI05459 females. We scored the proportion of offspring that were frusat15/ fruMI05459 that were produced across the first 10 days of offspring eclosion.

(f). Sensory modality assays

In all sensory modality assays, 5–7-day-old virgin females from the aforementioned interspecific crosses were paired with 5–7-day-old virgin D. melanogaster GFP-sperm males in 24 h no-choice mating assays, as described above. To test the effect of courtship song, males were anaesthetized and de-winged 48 h before the mating assays by clipping their wings (wing−) using dissection tweezers immediately distal to the hinge [51]. Control males were anaesthetized at the same time but were not de-winged (wing+). Males were given 48 h to recover then paired in no-choice mating assays. Assays were first conducted with fruMI05459 sim/melDis females and sim/melBal controls. The assays were conducted again with fruMI05459 and two additional deletions: fru4-40 and fruGAL4. A four-way comparison of copulation occurrence of males with or without wings when paired with sim/melDis or sim/melBal hybrid females were compared using logistic regression, as above. Copulation occurrence for wing+ versus wing− males in the additional disruption assays were compared using a two-proportion Z-test (α < 0.05).

To test whether fruitless is acting on female perception of olfactory or auditory signals, 48 h before the assay fruMI05459 sim/melDis females and sim/melBal control females were placed under CO2 anaesthesia and either left unaltered (ant+) or dissection tweezers were used to remove the last two segments of the females' antennae (ant−), which includes the aristae. Females were given 48 h to recover, then paired with males in no-choice mating assays with these females. The assays were conducted again with fruMI05459 and fruGAL4. A four-way comparison of copulation occurrence of sim/melDis or sim/melBal hybrid females with or without antennae were compared using logistic regression, as above. Copulation occurrence of ant+ versus ant− females in the additional disruption assays were compared using a two-proportion Z-test (α < 0.05).

To test whether substrate vibrations had an effect in female preference, 5–7-day-old virgin hybrid fruGAL4 sim/melDis and corresponding sim/melBal females were paired with 5–7-day-old virgin D. melanogaster GFP sperm males in a Plexiglas mating arena [52] placed on a granite base. The base, if left bare, does not allow transmission of the substrate vibrations produced by small insects [53]. The mating arena was coated with Insect-a-Slip Insect Barrier from BioQuip Products (Cat# 2871C), to prevent flies from climbing the walls or ceiling of the arena. For half of the chambers in the arena, the granite base was coated with 1% agarose gel approximately 2 mm thick to add a substrate for the control assays. The mating assays were performed for 24 h, as described above. A four-way comparison of copulation occurrence of sim/melDis and sim/melBal hybrid females with or without substrate were compared using logistic regression, as above.

3. Results and discussion

(a). Identification and confirmation of fruitless

We used overlapping, small deficiencies to fine-map one of the regions identified by Laturney & Moehring [19] to identify a small genomic region containing a single gene: fruitless (fru; figure 1b; electronic supplementary material, table S1). The small deletion fru4-40 has one breakpoint within the fru gene and is known to eliminate the sex-specific transcripts of fru [33]; the unrefined upstream breakpoint is encompassed by a non-significant deletion we tested (Df(3R)07280).

To confirm whether fru had an effect on female preference, we used the same conceptual approach as above, but using two alleles known to disrupt sex-specific fru expression (fruGAL4 and fruNP0021; [27,33,42,54,55]) and three transposable element insertions in fru that have yet to be fully characterized but may disrupt fru function (fruMI01850, fruKG00116 and fruMI05459 [56–58]). When there is an insertion in the D. melanogaster allele of fru in an inter-species hybrid, so that only the D. simulans fru allele is probably functional (sim/melDis), female receptivity towards D. melanogaster males was significantly reduced compared with controls in five of the six lines we tested (figure 1b,d; electronic supplementary material, table S1). The non-significant effect of fruGAL4 may be because its position in the 5′ region of the gene does not disrupt the causal transcripts. Combining the six independent tests of fru disruption (fru4-40, fruGAL4, fruNP0021, fruMI01850, fruKG00116 and fruMI05459) into a meta-analysis gives a very low meta-p value (Fisher's method: p < 10−8), supporting the conclusion that this locus affects female receptivity.

We then established that the effect on female receptivity is not due to aspects of the underlying genetic background. First, we observe that it is not due to hemizygosity, as fru hemizygous pure-species D. melanogaster females did not display a reduction in receptivity (figure 1d). In other words, the disruption itself does not generally affect female receptivity, and the effect depends on which allele is disrupted or ‘unmasked’.

The behaviour we observe is also not simply a general reduction in female receptivity towards all males due to removing the melanogaster allele and unmasking the simulans allele, rather than being due to the signals provided by D. melanogaster males in particular. We matched the fru allele being expressed to the species of the male in the assay by pairing sim/melDis females with D. simulans males. If the unmasking of the simulans allele does not affect general female receptivity, then when these females are tested with simulans males they should accept males at the same rate as control females. Females bearing any of the three melanogaster fru disruptions that we assayed mated similarly to the controls lacking this disruption (sim/melBal) when paired with D. simulans males (electronic supplementary material, table S3), indicating that females with only the simulans allele are not suffering a general reduction in receptivity. Further, our results are not due to defective fru processing causing masculinization of melDis females as this would be expected to reduce receptivity [59,60], which we did not observe in our control crosses; it also would induce aggression [61,62], which was not directly apparent in any of our assays.

To ensure that the effect of fru is species specific, we determined that this effect is not only present in a single strain of D. simulans by testing the fruMI01850 gene disruption in hybrids that were generated using two additional strains of D. simulans. As with the original strain, these strains of D. simulans produced the same significant effect of fru (p = 0.0001, p < 0.0001; electronic supplementary material, table S4). While this confirms the broad effect of this gene in more than one strain of simulans, we cannot rule out that some strains from the species' worldwide distribution may not display this effect; this warrants additional testing.

If fru is indeed involved in species-specific female preference behaviour, D. melanogaster-like female preference behaviour should be rescued after excising the transposable element insertion from one of the fru disruption lines. We chose to excise the fruMI05459 Minos element insertion as it showed a strong effect on female preference (figure 1d; electronic supplementary material, table S1). The fruMI05459 insertion disrupts at least some fru transcripts, as it qualitatively reduces transcription of P2 and eliminates transcription of P5 (figure 1e; electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and fruMI05459/fru4-40 males are behaviourally sterile (electronic supplementary material, table S5), as would be expected if the P1 transcript is functionally disrupted [33,34]. Homozygous deletion of P3 and P4 cause lethality; when we pair disruption fruMI05459 with a known fru null (frusat15), fruMI05459/frusat15 offspring are viable (25% expected, 24% seen: 86/357), indicating that this disruption does not appear to affect the functionality of transcripts P3 and P4. After excision, sequencing and RT-PCR to confirm a clean removal of the Minos element (figure 1e; electronic supplementary material, figure S2), we assayed female receptivity (figure 1f). Hybrid females with the excised Minos element mated significantly more (19/32) than hybrids bearing the disruption (3/32; p < 0.0001, Z = 4.21) and had only a slight non-significant reduction in mating frequency compared with control hybrids in which fru is intact (26/32; p = 0.0549, Z = 1.92). Thus, by removing the disruption in fru, we regained female receptivity towards D. melanogaster males, confirming the effect of fru on species-specific female preference.

(b). Identification of the fru transcript affecting female preference

To identify which fru transcript may be affecting female rejection behaviour, we first assessed the presence or absence of P1–P5 transcripts in females for five of the disruption lines we tested (electronic supplementary material, figure S1); fru4-40 was previously shown to disrupt P1 and P2 transcripts [33]. While the presence of fru transcript does not indicate functional transcript [34], most of the lines we tested had P1, P3 and P4 transcripts present, while several had reduced or absent P2 or P5. Based on these preliminary observations, and the potential to rule out P1, we then tested precise deletions of either the D. melanogaster fru P1 first exon or fru P2 first exon (fruΔP1 and fruΔP2, respectively) to determine if the transcripts from one of these exons are affecting inter-species female rejection. As we cannot be certain that a P2 deletion does not also subtly affect P5 expression, and to determine if a P2 transcript could plausibly affect behaviour via the female brain, we used RT-PCR to confirm that the P2 transcript, but not the P5 transcript, is expressed in female brains (figure 2d). Hybrid females bearing a melanogaster P1 or P2 disruption appear to be as attractive to D. melanogaster males as non-disruption females. Males initiate courtship (n = 32, p = 0.867, F = 3.094) and spend a total time courting (n = 32, p = 0.742, F = 0.299; electronic supplementary material, table S6) hybrid disruption females similarly to control females.

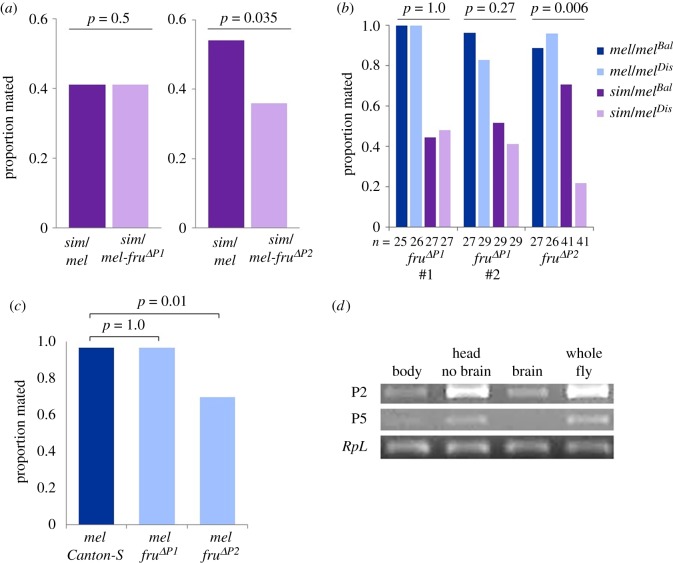

Figure 2.

Proportion of females mating when they contain fruΔP1 (independent deletions #1 and #2) or fruΔP2 targeted deletions of their melanogaster allele. Note that, for all hybrid females, the simulans fru allele is intact. (a) fruΔP1 (#1; n = 39) or fruΔP2 (n = 50) hybrid females, compared with hybrid Canton-S/simulans controls in a 24 h assay. (b) Hybrid females with a disruption (sim/melDis; light purple) compared with hybrid females without a disruption (sim/melBal; dark purple), pure species females with (mel/melDis; light blue) and without (mel/melBal; dark blue) a heterozygous disruption. Pure-species females assayed for 1 h; hybrid females assayed for 24 h. p-Values are for the interaction term between species (sim/mel versus mel/mel) and genotype (Dis versus Bal). (c) Pure species D. melanogaster females paired with D. melanogaster males for 1 h (n = 30); females are wild-type (Canton-S) or have a homozygous deletion (fruΔP1 or fruΔP2). (d) RT-PCR product from tissues taken from a female body (thorax and abdomen), head without the brain, brain, and whole fly for fru P2, fru P5, and the control gene RpL32. (Online version in colour.)

The receptivity of females was tested in two ways. First, for a comparison with the genetic background in which the deletions were made (Canton-S), hybrid females with the disruption were compared with hybrids made from wild-type Canton-S melanogaster (figure 2a). Second, to ensure that the disruption itself is not affecting behaviour, we tested the disruptions in the same manner as our original assays (figure 2b). Hybrid females bearing fruΔP1, and thus only expressing D. simulans P1 alleles, did not show reduced receptivity towards D. melanogaster males. In contrast, fruΔP2 hybrid females that only express D. simulans P2 alleles show reduced mating with D. melanogaster males (figure 2a,b; electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S7). Note that this finding does not rule out a potential role of other fru transcripts in female receptivity. Males actively court fruΔP2 hybrid females: during a 10 min assay males courted an average of 70% of the time and made 17 copulation attempts (n = 10; electronic supplementary material, table S8). The fruΔP2 hybrid females are also not simply lacking the display of copulation acceptance, but actively reject courting males an average of 26 times in a 10 min assay, via displays of ovipositor extrusion, kicking, and/or wing scissoring, and spent an average of 3 min in the 10 min assay actively moving away from the courting male (n = 10; electronic supplementary material, table S8). The effect of fruΔP2 on female receptivity is the first indication that one of the non-sex-specific fru transcripts may play an important role in behaviour. This finding challenges theoretical models that consider female preference genes to be separate from genes underlying the production of male traits, primarily due to the different morphological features involved in these two traits and the potential cost of intralocus sexual antagonism (e.g. [63,64]; but see [65,66]). The separate fru transcripts encoding female preference and male courtship traits may have facilitated this gene's preference-trait pleiotropy.

(c). Effect of homozygous P2 deletions in pure-species D. melanogaster females

We also tested whether the loss of P1 or P2 affects within-species female preference by assaying receptivity in pure species pairings. Male D. melanogaster court fruΔP1 and fruΔP2 homozygous deletion females for a similar amount of time as Canton-S control females (n = 30, p = 0.207, F = 1.606) but there is a difference in the time it takes for males to initiate courtship (n = 30, p = 0.0002, F = 3.103; electronic supplementary material, table S9). In pairwise comparisons, the latency to courtship is shorter for fruΔP1 (n = 30, p = 0.00028, t = 1.672) and fruΔP2 (n = 30, p = 0.0028, t = 1.672) females compared with the control, indicating that males are faster to initiate courtship with deletion females. However, although males court these females more rapidly, D. melanogaster females homozygous for the fruΔP2 deletion exhibit reduced mating with D. melanogaster males compared with fruΔP1 and Canton-S females (n = 30, p = 0.01, Z = 2.334; figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, table S9). When paired with D. simulans males in a 5-day mating assay period, there was no difference in copulation frequency among the homozygous deletions (P1: 1/15; P2: 0/15) compared with control (0/15; p = 0.154, Z = 1.017), but all three groups of females show very low mating in this inter-species assay, reducing our power to detect differences. These results suggest that the loss of D. melanogaster fru P2 significantly reduces female receptivity within species, but the loss of either fru P1 or fru P2 does not appear to increase female receptivity towards heterospecific males.

(d). Female evaluation of sensory signals via fru

Lastly, we wanted to assess whether the fru gene is involved in a female's assessment of an individual male courtship component, rather than in the integration of male courtship signals. Drosophila male courtship involves multimodal signals exchanged through a series of stereotypic courtship steps. During this exchange, the female assesses the male based on these signals and chooses to either copulate with or reject the male. The primary modalities that have historically been examined are the male auditory signal of courtship song produced by wing vibrations, which differs between these two species [67–69], and chemical pheromones, which also differ between these two species [70–72]. Removal or alteration of male song, or removal of female perception of song does not cause females to become fully receptive to heterospecific males [63,64], presumably because all of the other courtship components are still heterospecific, and a single negative courtship signal can be sufficient to induce female rejection. However, it is possible that the rejection induced by a single gene may result from the processing of a single component of courtship, and removal of that component might induce D. melanogaster-like receptivity in hybrid females bearing a fru disruption. Female hybrids bearing a disruption in another gene had their receptivity rescued upon removal of male courtship song [73], indicating that it is possible for single genes to affect receptivity via the presence of a single ‘negative’ signal.

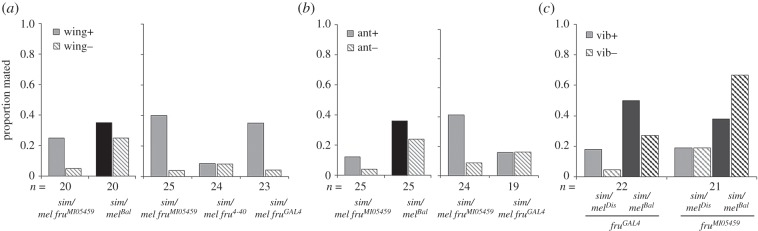

To test this, we attempted to remove or alter two primary individual components of either male courtship or female perception in mating assays involving female hybrids bearing a fru disruption that unmasks the D. simulans allele of fru. If fru is acting via only one of these sensory modalities, then removing that component will increase the receptivity of these hybrids towards D. melanogaster males. Removal of the wings of D. melanogaster males caused either no effect or a significant reduction in mating when these males were paired with hybrid females bearing a fru disruption (figure 3a; electronic supplementary material, tables S10 and S11), similar to what is seen when wings are removed in pure species matings of D. melanogaster [64,67]. Therefore, removal of this auditory signal does not rescue female receptivity in relation to the D. simulans fru allele. We then tested whether perception of auditory or olfactory information affects receptivity in the context of fru by removing the last two antennal segments and aristae of the female; these are the primary organs for sensing odorants and auditory signals, respectively [74]. We observed no significant difference in copulation upon removal of these organs (figure 3b; electronic supplementary material, tables S12 and S13). Lastly, we tested whether fru is acting via a recently discovered sensory modality: substrate-borne abdominal vibrations during courtship [75,76]. We used a granite surface to eliminate the transfer of these signals [53], but female receptivity did not increase upon removal of substrate vibrations in the context of fru (figure 3c; electronic supplementary material, table S14). Thus, fru does not appear to be acting through these single sensory modalities, and is probably either acting through the integration of multiple modalities, or via a signal or sensory organ other than the ones we assessed here.

Figure 3.

The removal of sensory modalities does not increase female receptivity towards D. melanogaster males. (a) Proportion of hybrid disruption fruMI05459 and control sim/melBal females that mate when paired with males with wings removed (wing−) versus those with wings intact (wing+). The assay was repeated for this disruption plus two additional disruptions (fru4-40, fruGAL4). (b) Proportion of hybrid disruption fruMI05459 and control sim/melBal females that mate when their last two antennal segments have been removed (ant−), which removes the primary sensory organs for both olfactory and auditory signals, compared with females with intact antennae (ant+). The assay was repeated for this disruption and fruGAL4. (c) Proportion of hybrid disruption fruMI05459 or fruGAL4 and control sim/melBal females that mated when placed on a vibrationless (vib−) versus control (vib+) substrate.

Identifying a genetic basis for behavioural isolation is critical for understanding the speciation process and the evolutionary history of such a reproductive barrier [77,78]. Here, we identify fru as a behavioural isolation gene that influences D. simulans female rejection of D. melanogaster males. This effect appears to be through the P2 group of transcripts of fru, the first behavioural role of a non-sex-specific transcript of this gene. Since the fru gene plays a role in sex determination and has highly conserved genetic sequence across multiple orders, it is possible that splice variants of this gene, and other genes involved in sex-differentiation pathways, may affect behavioural isolation in other species pairs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ben Rubin for statistical guidance and Laura Redondo assistance with vibration-less assays. We thank Megan Neville and Stephen Goodwin for helpful comments on the manuscript and providing the fruΔP1 and fruΔP2 deletion lines. Requests for fruΔP1 or fruΔP2 targeted deletion strains should be directed to Dr Stephen F. Goodwin, Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, University of Oxford.

Data accessibility

All data are provided in the manuscript and electronic supplementary material tables.

Authors' contributions

T.C., R.M.C. and A.J.M. designed all experiments. T.C., R.M.C. and K.B. performed behaviour assays. T.C. and A.J.M. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery grant and Ontario Early Researcher Award grant to A.J.M.

References

- 1.Bateman AJ. 1948. Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2, 349–368. ( 10.1038/hdy.1948.21) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trivers RL. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man (ed. Campbell B.), pp. 136–179. Chicago, IL: Aldine Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clutton-Brock T. 2007. Sexual selection in males and females. Science 318, 1882–1885. ( 10.1126/science.1133311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker G. 1983. Mate quality and mating decisions. In Mate choice (ed. Bateson PG.), pp. 141–166. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houde AE. 1987. Mate choice based upon naturally occurring color-pattern variation in a guppy population. Evolution 141, 1–10. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1987.tb05766.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houle D, Kondrashov AS. 2002. Coevolution of costly mate choice and condition-dependent display of good genes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 97–104. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1823) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne JA, Orr HA. 1997. ‘Patterns of speciation in Drosophila’ revisited. Evolution 51, 295–303. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03650.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson M, Simmons LW. 2006. Sexual selection and mate choice. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 296–302. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maan ME, Seehausen O. 2011. Ecology, sexual selection and speciation. Ecol. Lett. 14, 591–602. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01606.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto D, Jallon JM, Komatsu A. 1997. Genetic dissection of sexual behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42, 551–585. ( 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.551) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finley KD, Taylor BJ, Milstein M, McKeown M. 1997. dissatisfaction, a gene involved in sex-specific behavior and neural development of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 913–918. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.3.913) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki K, Juni N, Yamamoto D. 1997. Enhanced mate refusal in female Drosophila induced by a mutation in the spinster locus. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 32, 235–243. ( 10.1303/aez.32.235) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juni N, Yamamoto D. 2009. Genetic analysis of chaste, a new mutation of Drosophila melanogaster characterized by extremely low female sexual receptivity. J. Neurogenet. 23, 329–340. ( 10.1080/01677060802471601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laturney M, Moehring AJ. 2012. The genetic basis of female mate preference and species isolation in Drosophila. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 328392 ( 10.1155/2012/328392) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campesan S, Dubrova Y, Hall JC, Kyriacou CP. 2001. The nonA gene in Drosophila conveys species-specific behavioral characteristics. Genetics 158, 1535–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick MJ, Ben-Shahar Y, Smid HM, Vet LE, Robinson GE, Sokolowski MB. 2005. Candidate genes for behavioural ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 96–104. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moehring AJ, Llopart A, Elwyn S, Coyne JA, Mackay TF. 2006. The genetic basis of prezygotic reproductive isolation between Drosophila santomea and D. yakuba due to mating preference. Genetics 173, 215–223. ( 10.1534/genetics.105.052993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kronforst MR, Young LG, Kapan DD, McNeely C, O'Neill RJ, Gilbert LE. 2006. Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6575–6580. ( 10.1073/pnas.0509685103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laturney M, Moehring AJ. 2012. Fine-scale genetic analysis of species-specific female preference in Drosophila simulans. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 1718–1731. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02550.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanda P, Singh BN. 2012. Behavioural reproductive isolation and speciation in Drosophila. J. Biosci. 37, 359–374. ( 10.1007/s12038-012-9193-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barker J. 1967. Factors affecting sexual isolation between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Am. Nat. 101, 277–287. ( 10.1086/282490) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carracedo MC, Suarez C, Casares P. 2000. Sexual isolation between Drosophila melanogaster, D. simulans and D. mauritiana: sex and species specific discrimination. Genetica 108, 155–162. ( 10.1023/A:1004132414511) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sturtevant A. 1920. Genetic studies on Drosophila simulans. I. Introduction: hybrids with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 5, 488-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manning A. 1959. The sexual isolation between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Anim. Behav. 7, 60–65. ( 10.1016/0003-3472(59)90031-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis AW, Roote J, Morley T, Sawamura K, Herrmann S, Ashburner M. 1996. Rescue of hybrid sterility in crosses between D. melanogaster and D. simulans. Nature 380, 157–159. ( 10.1038/380157a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lachaise D, David JR, Lemeunier F, Tsacas L, Ashburner M. 1986. The reproductive relationships of Drosophila sechellia with D. mauritiana, D. simulans, and D. melanogaster from the Afrotropical region. Evolution 40, 262–271. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1986.tb00468.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stockinger P, Kvitsiani D, Rotkopf S, Tirián L, Dickson BJ. 2005. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell 121, 795–807. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasyukova EG, Vieira C, Mackay TF. 2000. Deficiency mapping of quantitative trait loci affecting longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 156, 1129–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis T, Kurihara J, Yoshino E, Yamamoto D. 2000. Genomic organisation of the neural sex determination gene fruitless (fru) in the Hawaiian species Drosophila silvestris and the conservation of the fru BTB protein-protein binding domain throughout evolution. Hereditas 132, 67–78. ( 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2000.00067.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertossa RC, van de Zande L, Beukeboom LW.. 2009. The fruitless gene in Nasonia displays complex sex-specific splicing and contains new zinc finger domains. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1557–1569. ( 10.1093/molbev/msp067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clynen E, Bellés X, Piulachs MD. 2011. Conservation of fruitless’ role as master regulator of male courtship behaviour from cockroaches to flies. Dev. Genes Evol. 221, 43–48. ( 10.1007/s00427-011-0352-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gempe T, Beye M. 2011. Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. Bioessays 33, 52–60. ( 10.1002/bies.201000043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anand A, et al. 2001. Molecular genetic dissection of the sex-specific and vital functions of the Drosophila melanogaster sex determination gene fruitless. Genetics 158, 1569–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin SF, Taylor BJ, Villella A, Foss M, Ryner LC, Baker BS, Hall JC. 2000. Aberrant splicing and altered spatial expression patterns in fruitless mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 154, 725–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryner LC, Goodwin SF, Castrillon DH, Anand A, Villella A, Baker BS, Hall JC, Taylor BJ, Wasserman SA. 1996. Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell 87, 1079–1089. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81802-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song H-J, et al. 2002. The fruitless gene is required for the proper formation of axonal tracts in the embryonic central nervous system of Drosophila. Genetics 162, 1703–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billeter JC, Rideout EJ, Dornan AJ, Goodwin SF. 2006. Control of male sexual behavior in Drosophila by the sex determination pathway. Curr. Biol. 16, R766–R776. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usui-Aoki K, et al. 2000. Formation of the male-specific muscle in female Drosophila by ectopic fruitless expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 500-506. ( 10.1038/35019537) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall JC. 1978. Courtship among males due to a male-sterile mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Behav. Genet. 8, 125–141. ( 10.1007/BF01066870) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siwicki KK, Kravitz EA. 2009. fruitless, doublesex and the genetics of social behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Opin Neurobiol. 19, 200–206. ( 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gailey DA, Hall JC. 1989. Behavior and cytogenetics of fruitless in Drosophila melanogaster: different courtship defects caused by separate, closely linked lesions. Genetics 121, 773–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee G, Foss M, Goodwin SF, Carlo T, Taylor BJ, Hall JC. 2000. Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. Dev. Neurobiol. 43, 404–426. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker BS, Taylor BJ, Hall JC. 2001. Are complex behaviors specified by dedicated regulatory genes? Reasoning from Drosophila. Cell 105, 13–24. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00293-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Philipsborn AC, Jörchel S, Tirian L, Demir E, Morita T, Stern DL, Dickson BJ. 2014. Cellular and behavioral functions of fruitless isoforms in Drosophila courtship. Curr. Biol. 24, 242–251. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neville MC, et al. 2014. Male-specific fruitless isoforms target neurodevelopmental genes to specify a sexually dimorphic nervous system. Curr. Biol. 24, 229–241. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; See https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arcà B, Zabalou S, Loukeris TG, Savakis C. 1997. Mobilization of a Minos transposon in Drosophila melanogaster chromosomes and chromatid repair by heteroduplex formation. Genetics 145, 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leader DP, Krause SA, Pandit A, Davies SA, Dow JAT. 2017. FlyAtlas 2: a new version of the Drosophila melanogaster expression atlas with RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq and sex-specific data. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D809–D815. ( 10.1093/nar/gkx976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Austin CJ, Guglielmo CG, Moehring AJ. 2014. A direct test of the effects of changing atmospheric pressure on the mating behavior of Drosophila melanogaster. Evol. Ecol. 28, 535–544. ( 10.1007/s10682-014-9689-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagarkar-Jaiswal S, et al. 2015. A genetic toolkit for tagging intronic MiMIC containing genes. Elife 4, e08469 ( 10.7554/eLife.08469) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krstic D, Boll W, Noll M. 2009. Sensory integration regulating male courtship behavior in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 4, e4457 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0004457) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dierick HA. 2007. A method for quantifying aggression in male Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2712–2718. ( 10.1038/nprot.2007.404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elias DO, Mason AC, Hoy RR. 2004. The effect of substrate on the efficacy of seismic courtship signal transmission in the jumping spider Habronattus dossenus (Araneae: Salticidae). J. Exp. Biol. 207, 4105–4110. ( 10.1242/jeb.01261) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimura K-I, Ote M, Tazawa T, Yamamoto D. 2005. fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature 438, 229-233. ( 10.1038/nature04229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kimura K, Hachiya T, Koganezawa M, Tazawa T, Yamamoto D. 2008. fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron 59, 759–769. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bellen HJ, et al. 2004. The BDGP gene disruption project. Genetics 167, 761–781. ( 10.1534/genetics.104.026427) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venken KJ, et al. 2011. MiMIC: a highly versatile transposon insertion resource for engineering Drosophila melanogaster genes. Nat. Methods. 8, 737–743. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1662) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gramates LS, et al. 2016. FlyBase at 25: looking to the future. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1), D663–D671. ( 10.1093/nar/gkw1016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aranha MM, Herrmann D, Cachitas H, Neto-Silva RM, Dias S, Vasconcelos ML. 2017. apterous brain neurons control receptivity to male courtship in Drosophila melanogaster females. Sci. Rep. 7, 46242 ( 10.1038/srep46242) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rideout EJ, Billeter J-C, Goodwin SF. 2007. The sex-determination genes fruitless and doublesex specify a neural substrate required for courtship song. Curr. Biol. 17, 1473–1478. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manoli DS, Foss M, Villella A, Taylor BJ, Hall JC, Baker BS. 2005. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature 436, 395-400. ( 10.1038/nature03859) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan Y-B, Kravitz EA. 2007. Specific subgroups of FruM neurons control sexually dimorphic patterns of aggression in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19 577–19 582. ( 10.1073/pnas.0709803104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ritchie MG, Halsey EJ, Gleason JM. 1999. Drosophila song as a species-specific mating signal and the behavioural importance of Kyriacou & Hall cycles in D. melanogaster song. Anim. Behav. 58, 649–657. ( 10.1006/anbe.1999.1167) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomaru M, Doi M, Higuchi H, Oguma Y. 2000. Courtship song recognition in the Drosophila melanogaster complex: heterospecific songs make females receptive in D. melanogaster, but not in D. sechellia. Evolution 54, 1286–1294. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00561.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marcillac F, Grosjean Y, Ferveur JF. 2005. A single mutation alters production and discrimination of Drosophila sex pheromones. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 303–309. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2971) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McNiven VT, Moehring AJ. 2013. Identification of genetically linked female preference and male trait. Evolution 67, 2155–2165. ( 10.1111/evo.12096) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ewing AW, Bennet-Clark H. 1968. The courtship songs of Drosophila. Behaviour 31, 288–301. ( 10.1163/156853968X00298) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moulin B, Rybak F, Aubin T, Jallon JM. 2001. Compared ontogenesis of courtship song components of males from the sibling species, D. melanogaster and D. simulans. Behav. Genet. 31, 299–308. ( 10.1023/A:1012231409691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moulin B, Aubin T, Jallon JM. 2004. Why there is a one-way crossability between D. melanogaster and D. simulans? Genetica 120, 285–292. ( 10.1023/B:GENE.0000017650.45464.f4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cobb M, Jallon JM. 1990. Pheromones, mate recognition and courtship stimulation in the Drosophila melanogaster species sub-group. Anim. Behav. 39, 1058–1067. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80778-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pardy JA, Rundle HD, Bernards MA, Moehring AJ. 2019. The genetic basis of female pheromone differences between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Heredity 122, 93–109. ( 10.1038/s41437-018-0080-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rouault JD, Marican C, Wicker-Thomas C, Jallon JM. 2004. Relations between cuticular hydrocarbon (HC) polymorphism, resistance against desiccation and breeding temperature: a model for HC evolution in D. melanogaster and D. simulans. Genetica 120, 195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Calhoun R. 2017. Genetics of female interspecific mate rejection in species of Drosophila. Electronic Dissertation Repository. Western University. 4621. See https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4621.

- 74.Vosshall LB, Stocker RF. 2007. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 505–533. ( 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094306) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mazzoni V, Anfora G, Virant-Doberlet M. 2013. Substrate vibrations during courtship in three Drosophila species. PLoS ONE 8, e80708 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0080708) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fabre CC, Hedwig B, Conduit G, Lawrence PA, Goodwin SF, Casal J. 2012. Substrate-borne vibratory communication during courtship in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 22, 2180–2185. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coyne JA, Orr HA. 2004. Speciation. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- 78.Moehring AJ, Boughman JW. 2019. Veiled preferences and cryptic female choice could underlie the origin of novel sexual traits. Biol. Lett. 15, 20180878 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0878) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in the manuscript and electronic supplementary material tables.