Abstract

Background

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) in pediatric populations accounts for more than half of pediatric strokes and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Pediatric AIS can present with nonspecific symptoms or symptoms that mimic alternate pathology.

Case Report

A 4-month-old female presented to the emergency department for fever, decreased oral intake, and “limp” appearance after antibiotic administration. She was febrile, tachypneic, and hypoxic. Her skin was mottled with 3-s capillary refill, her anterior fontanelle was tense, and she had mute Babinski reflex bilaterally but was moving all extremities. The patient was hyponatremic, thrombocytopenic, and tested positive for influenza A. A computed tomography scan of the brain revealed an acute infarction involving the right frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes in addition to hyperdensities concerning for thrombosed cortical veins. The patient was transferred for specialty evaluation and was discharged 2 weeks later on levetiracetam.

Why Should an Emergency Physician be Aware of This?

Pediatric AIS can present with nonspecific symptoms that mimic alternate pathology. A high level of suspicion is needed so as not to miss the diagnosis of pediatric AIS in the emergency department. A thorough neurologic assessment is warranted, and subtle abnormalities should be investigated further.

Keywords: cerebrovascular accident, influenza A, ischemic stroke, pediatric stroke, stroke

Introduction

Stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) can be ischemic, hemorrhagic, or both, and result in devastating neurologic injury. Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) usually results from arterial occlusion or venous occlusion of cerebral veins or sinuses, whereas hemorrhagic stroke is often caused by bleeding from rupture of a cerebral artery or hemorrhagic conversion into the site of an AIS.

Ischemic stroke accounts for 55% of strokes in children, and there is significant associated morbidity and mortality, with approximately 10–25% of cases resulting in death, ≤33% developing recurrence, and 66% with persistent neurologic deficits, seizure disorders, learning problems, or developmental problems 1, 2, 3. Population studies show a pediatric AIS incidence rate of 3.3 per 100,000 children, but this may actually be higher because pediatric AIS can be undiagnosed or misdiagnosed (3). The risk factors for pediatric AIS differ from those of adult AIS, with respiratory infections emerging as a risk factor for pediatric and young adult AIS.

The early recognition of pediatric AIS is imperative, but the diagnosis can be challenging because patients can present with subtle symptoms, symptoms can mimic alternate pathology, and clinicians may have a low level of suspicion, especially during respiratory season. This case highlights the importance of being clinicially vigilant so as not to miss the diagnosis of pediatric AIS.

Case Report

A 4-month-old female presented to the emergency department (ED) for fever, decreased oral intake, and “limp” appearance after antibiotic administration. She was seen in the ED 3 weeks earlier for wheezing, was diagnosed with respiratory syncytial virus and coronavirus HKU1 19 days before presentation, and began taking cefdinir that was prescribed by her pediatrician for otitis media 3 days before presentation. The child’s guardian noted that she appeared “limp” after each dose of cefdinir. The guardian noted that the child had a fever of 38.3°C and decreased oral intake (but did not specify exact intake amounts), which prompted this ED visit. The guardian had not witnessed any seizure-like activity or tonic–clonic jerking. The relevant medical history included remote intrauterine drug exposure, bilateral otitis media undergoing treatment with cefdinir, and no known cardiac abnormalities.

Vitals in the ED were notable for heart rate of 160 beats/min, temperature 38.2°C which improved to 36.8°C after acetaminophen, a respiratory rate of 48 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation 80%, improving to respiratory rate 27 breaths/min and oxygen saturation 100% on 2 L of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula. Her initial blood pressure was 99/61 mm Hg. The physical examination was notable for a tense fontanelle, mottled skin, and 3-s capillary refill but an appropriately interactive child with nontoxic appearance. Pupils were 4 mm bilaterally and extraocular muscles were intact. The child had normal strength in all extremities and a symmetric smile, but absent Babinski bilaterally. The initial venous blood gas showed a pH of 7.39 (normal 7.32–7.42), lactate 2.1 mmol/L (normal 0.90–1.70 mmol/L), glucose 73 mg/dL (normal 65–110 mg/dL), sodium 130 mmol/L (normal 137–145 mmol/L), ionized calcium 4.40 mg/dL (normal 4.5–5.3 mg/dL), and potassium 4.13 mmol/L (normal 3.5–5.3 mmol/L). Her white blood cell count was 14.7 K/uL (normal 6.0–17.0 K/uL) with 35% bands and platelets were 637 K/uL (normal 130–450 K/uL). Her blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio was 7:0.2 mg/dL (normal 4–19:0.16–0.39 mg/dL). The patient was started on a normal saline bolus and empiric coverage with ceftriaxone given that she was receiving cefdinir at home for otitis media. Her chest radiograph showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormality, urinalysis showed no infection, and urine drug screen was negative. The respiratory panel was positive only for influenza A.

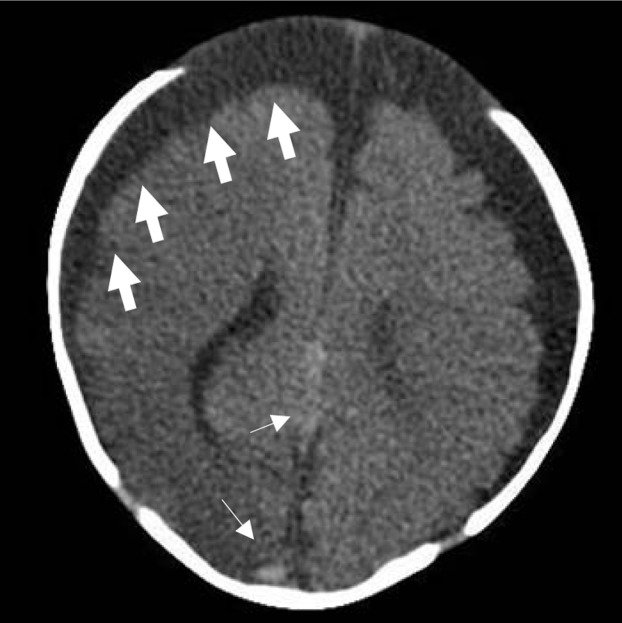

In the ED, the child was noted to have a brief nonsustained 3-s episode of twitching of the left thigh without tonic–clonic jerking. The basic metabolic panel returned with a sodium of 124 mmol/L (normal 136–145 mmol/L). The decision was made to obtain a computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain without contrast in the setting of reported “limp” appearance after antibiotics at home, and absent Babinski reflex bilaterally, with thigh twitching in the ED. The CT scan revealed a right cerebral hemisphere hypodensity concerning for acute infarction involving the right frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes in addition to hyperdensities concerning for thrombosed cortical veins (Figure 1 ). The patient was transferred for neurology and neurosurgical evaluation. A lumbar puncture was not performed in the ED because of the CT findings, and antivirals were not started in the ED because of the urgency of the patient’s condition. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain without contrast showed recent infarct without hemorrhagic conversion involving the territories of the right middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery territories, with additional findings suggestive of thromboembolic disease. MR angiography of the brain and neck showed no aneurysm, vascular malformation, or occlusion, and MR venography of the brain showed no evidence of venous sinus thrombosis. Further work-up at the outside hospital revealed no hypercoagulability with prothrombin time 12.6 s (normal 11.9–15.0 s), partial thromboplastin time 33.4 s (normal 25.1–36.5 s), and an international normalized ratio of 0.9. The patient was diagnosed with a small patent foramen ovale with trivial left to right shunt and asymmetric septal hypertrophy by cardiology, but this was not felt to be the underlying etiology for the patient’s AIS. No neurosurgical intervention was required during her 2-week admission, and the child was discharged home on levetiracetam.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the head showing right cerebral hemisphere hypodensity involving the right frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes (thick arrows) concerning for acute cerebral infarct in addition to hyperdensities (thin arrows) concerning for thrombosed cortical veins. There are prominent extra-axial spaces bilaterally, suggesting volume loss. The front of the skull is intact but is not visible in this image.

Discussion

Common causes of pediatric AIS include congenital heart disease, sickle cell anemia, coagulation disorders, extracranial carotid dissection, Haemophilus influenzae meningitis, and varicella infection, although in 33–65% of cases no definitive cause is found 2, 3, 4. While the exact pathophysiologic mechanism by which influenza causes AIS is poorly studied, published literature recognizes AIS as a neurologic complication of influenza infection. To our knowledge, 2 reported cases of pediatric AIS caused by influenza virus infection have been reported in the literature. A 4-year-old male with influenza A was diagnosed with a subacute infarct of the left middle cerebral artery, and a 9-month-old female diagnosed with influenza HIN1 was diagnosed with a left posterior middle cerebral artery stroke 5, 6. Infectious influenza virus has a prothrombotic effect by activating procoagulant pathways and inhibiting anticoagulant and fibrinolysis pathways, and this patient’s influenza A infection likely contributed to this patient’s AIS (7). Poor oral intake and dehydration may have been contributing complicating factors, although the patient’s blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio was normal on initial laboratory assessments. Fullerton et al. also found that infection transiently increased the risk of childhood AIS, with as many as 39% of patients with AIS reporting infection in the preceding 4 weeks and 18% in the preceding 1 week (adjusted odds ratio 6.5 [95% confidence interval 3.3–13] for infection in the previous week) (8).

Infants with AIS often present with nonspecific symptoms, making it challenging to diagnose AIS. AIS in children frequently presents with a focal neurologic deficit, and hemiplegia is present in ≤94% of cases (2). However, infants and toddlers may present with increased crying, sleepiness, irritability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, and sepsis-like symptoms 2, 9. These symptoms can easily be attributed to alternate pathology, resulting in the potential for a missed diagnosis. A thorough neurologic examination is necessary, and abnormal findings can be subtle. A tense anterior fontanelle on examination can be indicative of increased intracranial pressure, and should be investigated further (10). The published literature indicates that the extensor plantar reflex, commonly referred to as Babinski sign, is present in most infants, with transition to a flexor response at approximately 6 months of age 11, 12. The mute Babinski response in this case was a subtle clue warranting further evaluation.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

A high level of suspicion is needed in order to diagnose AIS in the pediatric population because patients with pediatric AIS can present with nonspecific symptoms, often resembling sepsis. Respiratory infections, including influenza, have been recognized as a cause of pediatric AIS. Early diagnosis can be life-saving, and therefore even subtle abnormalities on physician examination warrant further work-up.

Footnotes

Reprints are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Carvalho K.S., Garg B.P. Arterial strokes in children. Neurol Clin. 2002;20:1079–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(02)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsze D.S., Valente J.H. Pediatric stroke: a review. Emerg Med Int. 2011;2011:734506. doi: 10.1155/2011/734506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch J.K., Hirtz D.G., DeVeber G., Nelson K.B. Report of the national institute of neurological disorders and stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Sulaiman A., Bademosi O., Ismail H., Magboll G. Stroke in Saudi children. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:295–298. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell M.L., Buchhalter J.R. Influenza A-associated stroke in a 4-year-old male. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honorat R., Tison C., Sevely A., Cheuret E., Chaix Y., Claudet I. Influenza A (H1N1)-associated ischemic stroke in a 9-month-old child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:368–369. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31824dcaa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grau A.J., Urbanek C., Palm F. Common infections and the risk of stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:681–694. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fullerton H.J., Hills N.K., Elkind M.S., Dowling M.M., Wintermark M., Glaser C.A. Infection, vaccination, and childhood arterial ischemic stroke: results of the VIPS study. Neurology. 2015;85:1459–1466. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer-Heim A.D., Boltshauser E. Spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage in children: aetiology, presentation and outcome. Brain Dev. 2003;25:416–421. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roach E.S., Lo W.D., Heyer G.L., Roach E.S. 3rd ed. DemosMedical; New York: 2012. Pediatric stroke and cerebrovascular disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumhar G.D., Dua T., Gupta P. Plantar response in infancy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6:321–325. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3798(02)90620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gingold M.K., Jaynes M.E., Bodensteiner J.B., Romano J.T., Hammond M.T. The rise and fall of the plantar response in infancy. J Pediatr. 1998;133:568–570. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]