Abstract

This article discusses key concepts important for mucosal immunity. The mucosa is the largest immune organ of the body. The mucosal barrier (the tight junctions and the “kill zone”) along with the mucosa epithelial cells maintaining an anti-inflammatory state are essential for the mucosal firewall. The microbiome (the microorganisms that are in the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and reproductive tract) is essential for immune development, homeostasis, immune response, and maximizing animal productivity. Mucosal vaccination provides an opportunity to protect animals from most infectious diseases because oral, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and reproductive mucosa are the main portals of entry for infectious disease.

Keywords: Bovine, Mucosal, Immunology, Gastrointestinal, Respiratory, Reproductive, Microbiome

Key points

-

•

The largest organ of the immune system is the mucosa making the management of it essential for productivity and health.

-

•

The mucosal barrier consists of mucous, antimicrobial peptides, and IgA and is a “kill zone” to prevent microbial invasion of the epithelium.

-

•

The mucosal epithelial cells are key cells that maintain the “kill zone” and “mucosal firewall” and respond to metabolites and microbial components from the lumen and signals from immune cells to maintain tight junctions and prevent leaky gut.

-

•

The mucosal immune system has a unique circulatory system where immune cells that have activated in mucosal region recirculate to mucosal regions, a system termed the common mucosal system.

Introduction

In the last decade, there has been an explosion of knowledge on the mucosal immune system with substantial implications for cattle health. The concept of microbiome and its interaction with epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal (GI), reproductive, and mammary systems to influence immune function is discussed in detail by Diego E. Gomez and colleagues’ article, “The Cattle Microbiota and the Immune System: An Evolving Field,” in this issue. The use of nutraceuticals and their interaction with the microbiome and GI tract (GIT) is discussed in detail by Michael A. Ballou and colleagues’ article, “Neutraceuticals: An Alternative Strategy for the Use of Antimicrobials,” in this issue. In this article, we review key concepts important for mucosal immunity including epithelial cell immune function in the GI, respiratory, and reproductive tract; the common mucosal system; and vaccine and disease responses. It is now understood that the maturation of the immune responses begin where microorganisms and/or their products interact with epithelial cells of the mucosa in the neonatal calf (discussed in Diego E. Gomez and colleagues’ article, “The Cattle Microbiota and the Immune System: An Evolving Field,” elsewhere in this issue) and is necessary for proper development of the immune system and regulation and maintenance of immune homeostasis.

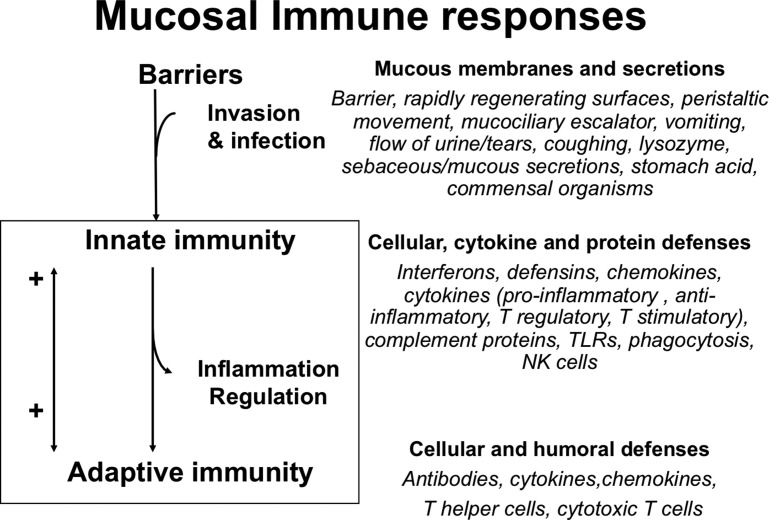

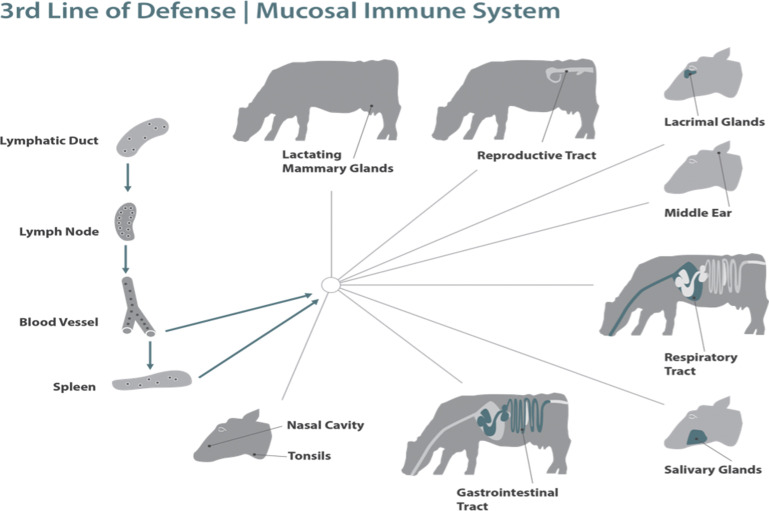

The mucosal immune system provides the first immune defense barrier for more than 90% of potential pathogens and represents the largest immune organ in the body. The mucosal immune system is an integrated system that fortifies the mucosal barrier with immune reinforcements from the innate and adaptive response and at the same time regulates and engages the immune system (Fig. 1 ) and has a greater concentration of antibodies than any other tissue in the body. It must not only protect against harmful pathogens but the mucosal system also tolerizes the immune system to dietary antigens and normal microbial flora. If the barrier is breached the next line of defense is the innate immune response in the lamina propria (LP) with phagocytic cells and production of various cytokines, chemokines, and proteins that not only provide antimicrobial protection but also recruit cells through the proinflammatory process and activate the acquired immune response (see Fig. 1). The acquired immune response with its myriad of B cells, T cells, cytokines, and antibodies provides the pathogen-specific memory with continued duration protective for subsequent infections with the same pathogen (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mucosal immune responses: the barrier, innate, and adaptive immune components. NK, natural killer cell; TLR, toll-like receptor.

(From C. Chase, Enteric Immunity Happy Gut, Healthy Animal. Elsevier. 2018; 34(1); with permission.)

Mucosal firewall: the mucous barrier, mucosal epithelial cells, and lamina propria

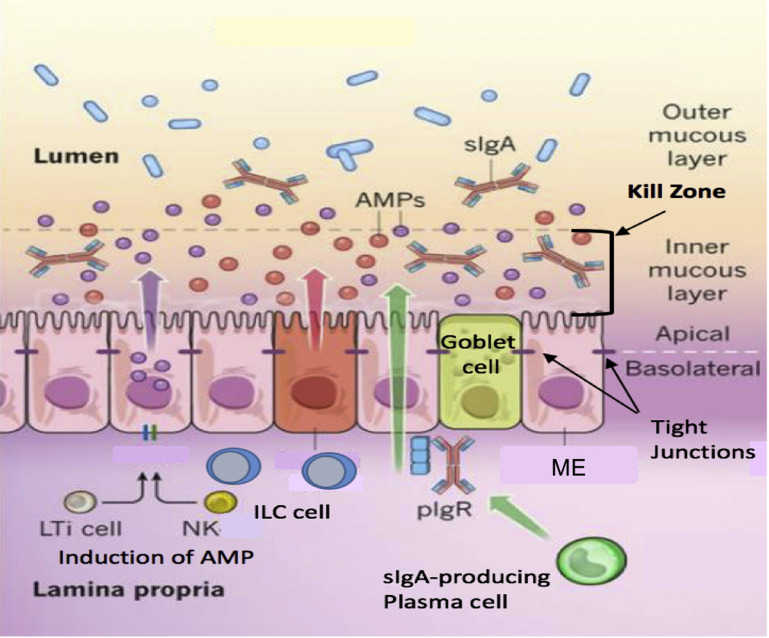

The health of the mucosa depends on three distinct structures: (1) the mucous barrier, (2) the mucosal epithelial cell, and (3) the immune cells of the LP. The mucous barrier consists of the mucous and mucins, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and IgA. The goblet cells in the mucosa secrete mucous and mucins that constitute the major portion of the barrier (Fig. 2 ).1, 2, 3 Mucins are also produced to a lesser degree by mucosa epithelial cells.4 The mucous barrier contains AMPs produced by the enterocytes and ciliated epithelial cells (CEC) (see Fig. 2; Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9 ). Secretory IgA (sIgA) is produced when dimeric IgA is secreted by the plasma cells in the LP and is transported to the mucosal surface of the epithelial cell. The inner mucous layer along with the AMPs and sIgA form a “killing zone” that few pathogens or commensals have evolved strategies to penetrate (see Fig. 2). This killing zone along with the tight junctions that knit the enterocytes and CEC form a barrier against pathogens.

Fig. 2.

The mucosal barrier. Distinct subpopulations of mucosal epithelial cells (ME) are integrated into a continuous, single cell layer that is divided into apical and basolateral regions by tight junctions. ME sense the microbiota and their metabolites to induce the production of AMPs. Goblet cells produce mucin and mucous, which is organized into a dense, more highly cross-linked inner proteoglycan gel that forms an adherent inner mucous layer, and a less densely cross-linked outer mucous layer. The outer layer is highly colonized by constituents of the microbiota. The inner mucous layer is largely impervious to bacterial colonization or penetration because of its high concentration of bactericidal AMPs, and commensals specific secretory IgA, which is moved from their basolateral surface, where it is bound by the receptor, to the inner mucous layer. Responding to the microbiotal components, innate lymphoid cells, lymphoid tissue inducer cells, and NK cells produce cytokines, which stimulate AMP production and maintain the epithelial barrier. ILC, innate lymphoid cells; LTi, lymphoid tissue inducer cells; pIgR, polymeric Ig receptor; sIgA, secretory IgA.

(Adapted from Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489(7415):231-241; with permission.)

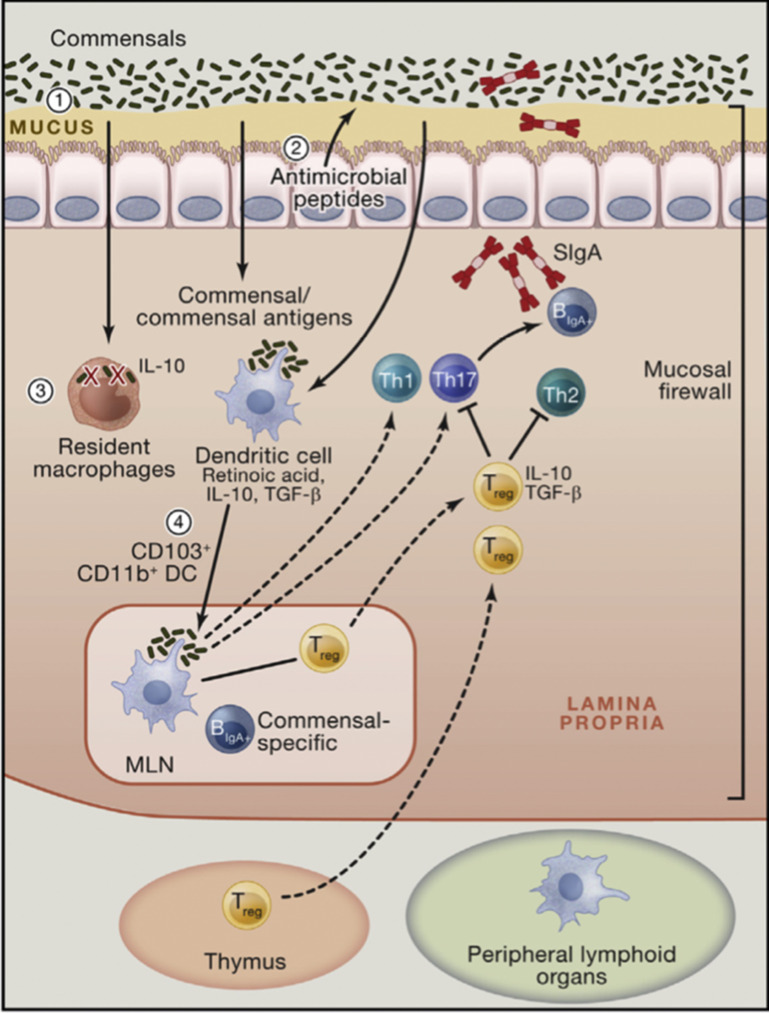

Fig. 3.

The mucosal firewall. (1) The mucus represents the primary barrier limiting contact between the microbiota and host tissue preventing microbial translocation. (2) Epithelial cells produce antimicrobial peptides that also play a significant role in limiting exposure to the commensal microbiota. (3) Translocating commensals are rapidly eliminated by tissue-resident macrophages. (4) Commensals or commensal antigens can also be captured by dendritic cells (DCs) that traffic to the mesenteric lymph node from the lamina propria but do not penetrate further. Presentation of commensal antigens by these DCs leads to the differentiation of commensal-specific regulatory cells, Th17 cells, and IgA-producing B cells. Commensal-specific lymphocytes traffic to the lamina propria and Peyer patches. In the Peyer patches, regulatory T cells can further promote class switching and IgA generation against commensals. The combination of the epithelial barrier, mucus layer, IgA, and DCs and T cells comprises the mucosal firewall, which limits the passage and exposure of commensals to the gut. IL, interleukin; MLN, mesenteric lymph nodes; TGF, transforming growth factor; Treg, regulatory T cells.

(Adapted from Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121-141; with permission.)

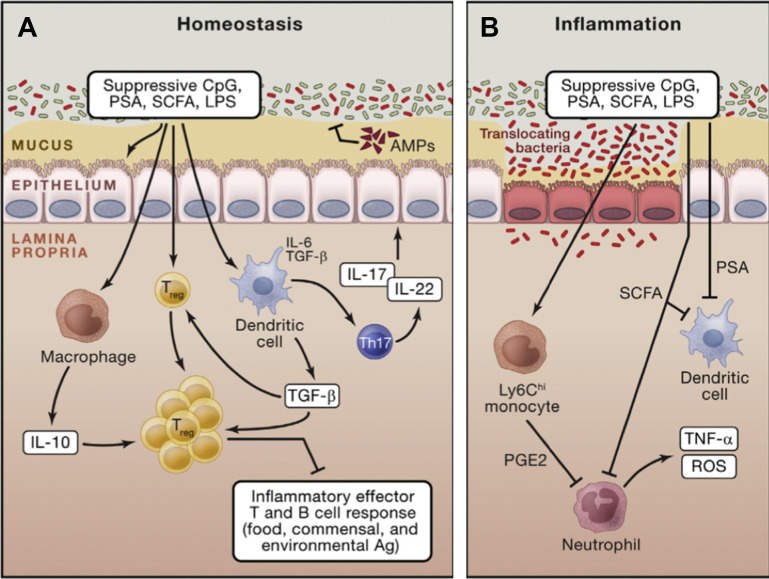

Fig. 4.

Mucosal immune regulation during homeostasis and inflammation. (A) Commensals promote the induction of regulatory T cells via direct sensing of microbial products or metabolites by T cells or dendritic cells. Further commensals promote the induction of Th17 cells that can regulate the function and homeostasis of epithelial cells. In the context of inflammation, similar mechanisms may account for the regulatory role of the microbiota. (B) Commensal-derived metabolites can also have a local and systemic effect on inflammatory cells. For example, short-chain fatty acids can inhibit neutrophil activation. On entrance in the tissue, inflammatory monocytes can also respond to microbial-derived ligands by producing mediators, such as prostaglandin E2, which limit neutrophil activation and tissue damage. CpG, cytosine-polyguanine nucleotides; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PSA, polysaccharide A; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

(Adapted from Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121-141; with permission.)

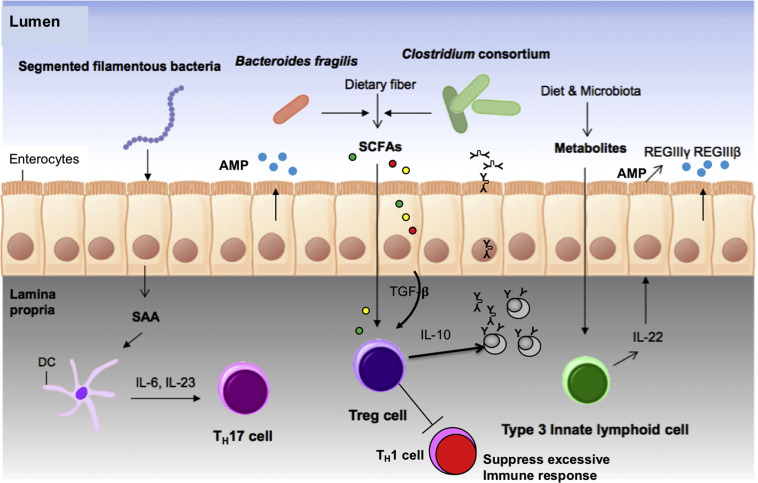

Fig. 5.

Contribution of commensals to ME cells and immunity. ME produce serum amyloid A protein after exposure to filamentous bacteria (related to Clostridium), which activates DCs to produce IL-6 and IL-23, resulting in the generation of Th17 cells that are important for T-cell development. Clostridium consortium and Bacteroides fragilis produce SCFAs from dietary carbohydrates that induce directly or indirectly by the production of TGF-β by the ME, the differentiation of Treg cells to enhance IgA production and to help minimize inflammatory response. Diet- or microbiota-derived metabolites upregulate the number of IL-22-secreting type 3 innate lymphoid cells that induce the production of antimicrobial peptides by the ME (AMP/HDP-REGIIIΒ and REGIIIγ) from epithelial cells. SAA, serum amyloid A.

(Adapted from Kim D, Yoo S-A, Kim W-U. Gut microbiota in autoimmunity: potential for clinical applications. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39(11):1565-1576; with permission.)

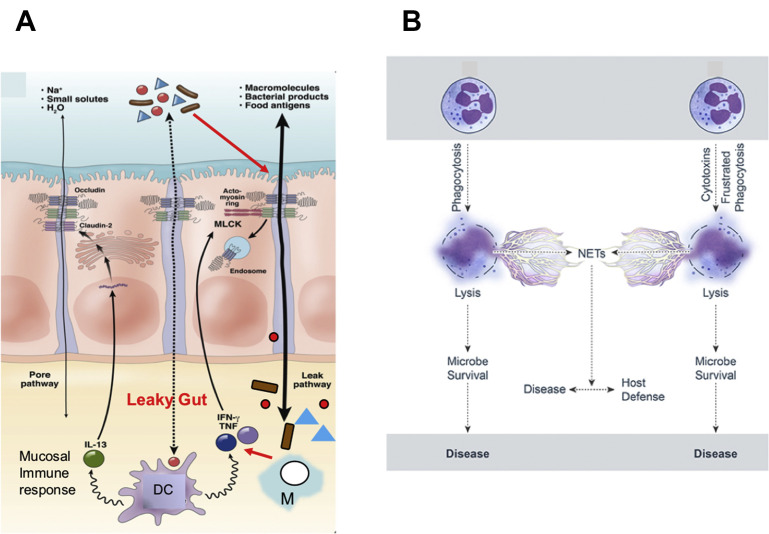

Fig. 6.

Innate immunity and the mucosa. (A) Pathogenesis of leaky gut. The mucosal barrier normally restricts passage of luminal contents, including microbes and their products, but a small fraction of these materials do cross the tight junction. This diagram shows how DCs and macrophages react to these materials. These innate immune cells release cytokines that exert proinflammatory (TNF and interferon-γ) and anti-inflammatory (IL-13) effects. If proinflammatory signals dominate and signal to the ME, MLCK can be activated to cause barrier dysfunction through the leak pathway, allowing an increase in the amount of luminal material presented to immune cells. In the absence of appropriate immune regulation, immune activation may cause further proinflammatory immune activation, cytokine release, and barrier loss, resulting in a self-amplifying cycle that can result in disease. (B) Neutrophil collateral damage from neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) formation. Neutrophil lysis after phagocytosis. Cytolysis is programmed (eg, necroptosis) or caused by direct damage. Neutrophil lysis is caused by cytolytic toxins, pore-forming agents, physical injury, or frustrated phagocytosis. This can result in the formation of NETs during neutrophil lysis. Hydrolytic enzymes–DNA complexes are released in the NETs, enhancing the proinflammatory response and tissue destruction, contributing to collateral damage and disease. IFN, interferon; M, macrophage; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase.

(Adapted from Odenwald MA, Turner JR. Intestinal permeability defects: is it time to treat? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11(9):1078, with permission; and Kobayashi SD, Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Influence of microbes on neutrophil life and death. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017;7(4):159, with permission.)

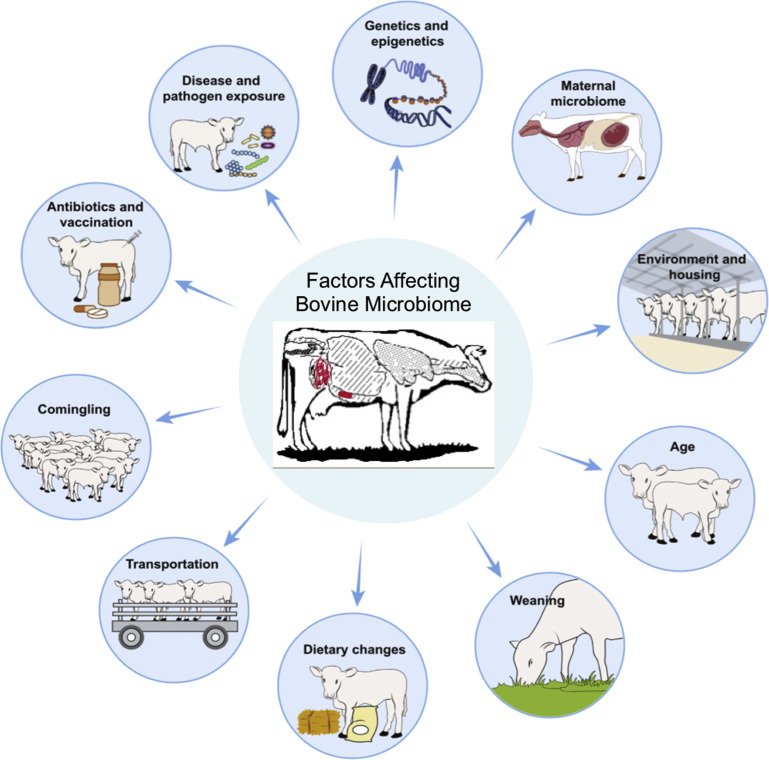

Fig. 7.

Factors affecting the development of the bovine microbiota. Microbiota developments are highly dynamic and are shaped by various host and environmental factors, including host genetics, mode of delivery, diet and the microbiota of the mother, environmental housing, weaning, feeding type, transportation, comingling, antibiotic treatment, vaccination, and pathogen exposure.

(Adapted from Zeineldin M, Lowe J, Aldridge B. Contribution of the Mucosal Microbiota to Bovine Respiratory Health. Trends Microbiol. May 2019; with permission.)

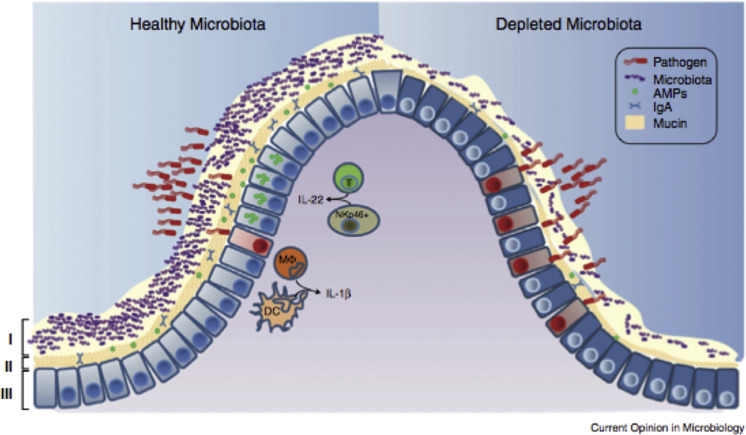

Fig. 8.

Healthy mucosal defenses and mucosal dysbiosis. The intestinal microbiota promotes three levels of protection against enteric infection. (I) Saturation of colonization sites and competition for nutrients by the microbiota limit pathogen association with host tissue. (II) Kill zone. Commensal microbes prime barrier immunity by driving expression of mucin, IgA, and AMPs that further prevents pathogen contact with host mucosa. (III) Finally, the microbiota enhances immune responses to invading pathogens. This is achieved by promoting IL-22 expression by T cells and NK cells, which increases epithelial resistance against infection, and priming secretion of IL-1b by intestinal monocytes (MΦ) and DCs, which promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells into the site of infection. In conditions where the microbiota is absent there is reduced competition, barrier resistance, and immune defense against pathogen invasion.

(From Khosravi A, Mazmanian SK. Disruption of the gut microbiome as a risk factor for microbial infections. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16(2):221-227; with permission.)

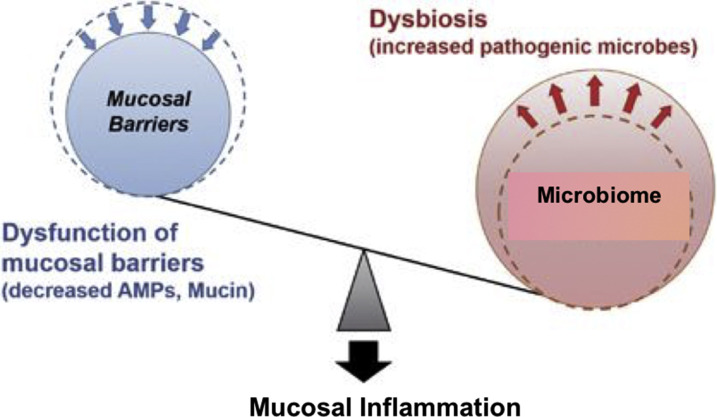

Fig. 9.

Microbial dysbiosis promotes susceptibility to mucosal inflammation. Dysfunction of mucosal barriers because of decreased production of AMPs and mucin allows intestinal bacteria to gain access to gut immune cells, thereby contributing to the development of intestinal inflammation. Dysbiosis induced by environmental factors, such as a high-fat diet and various antimicrobials and stressors, accelerates intestinal inflammation in situations where the mucosal barrier is disrupted.

(Adapted from Okumura R, Takeda K. Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(5):e338. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.20 with permission.)

The mucosal epithelium (ME) are the cells that line the GIT, uterus, and upper respiratory tract (URT). The ME is important not only for the animal’s health and productivity by their normal function (secretion and absorption in the gut, fetal development in the uterus, and oxygen exchange and clearance of particulate and pathogens for proper lung function in the URT), but these epithelial cells (known as enterocytes in the gut and CEC in the URT) are the first responders to microorganisms. The epithelial cells are coated with mucus-glycocalyx layer (see Fig. 2) that helps protect cells but are continually in contact with commensal and pathogenic organisms (see Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Because the ME is constantly in contact with microorganisms, their response is quite different.5 The mucous barrier is first line of defense and ME provide several defensive tools. One of the major defensive tools of the ME are AMP (host defense proteins) that are released into the mucous barrier and their ME production is stimulated by microbial components or products and/or the immune system (see Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, 8 and 9). AMPs are cationic molecules produced to defend the host against microbial pathogens. AMP act as lytic enzymes that disturb the microbial cell membrane.6 The AMPs go by different names (ie, defensins, REGIII, lactoferricin) and possess a wide spectrum of antimicrobial activity (at even low micromolar concentrations) against bacteria, fungi, and some enveloped viruses. AMPs attach to the microbial membrane and disrupt it by forming a pore that leads to the efflux of ions and nutrients.5 ME cells also export IgA and IgG produced by B cells in the LP to the mucous barrier. In addition to providing transport for immunoglobulin through the cell, the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor also adds a secretory component to IgA that lengthens the half-life of IgA (see Fig. 2).1 Secretory IgG (sIgG) in the nasal and URT and the reproductive tract is as or more important than sIgA.7 A third defensive component to the mucosal barrier that ME contributes are tight junctions (see Figs. 2 and 6).8 These structures consist of several highly regulated structural proteins that have the ability to contract or relax to affect the passage of molecules and ions through the space between cells. When the tight junctions breakdown, this allows the epithelium to become leaky and the inflammatory syndrome associated with it is referred to as “leaky gut”(see Fig. 6).9 This leakiness also occurs in the respiratory and reproductive tract.

ME have important immune regulatory functions that affect the mucous barrier, tight junctions, and the innate and adaptive immune cells in the LP.10 Like other immune cells, they use pattern-recognition receptors,11 including the toll-like receptors (TLR) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, to monitor pathogen-associated molecular patterns to recognize danger from microbes and induce different signaling pathways to activate the immune system against infection (discussed in Diego E. Gomez and colleagues’ article, “The Cattle Microbiota and the Immune System: An Evolving Field,” elsewhere in this issue). They do this by detecting microbial components, such as lipopolysaccharide (gram-negative bacteria) and cytosine-polyguanine nucleotides (found in bacteria and viruses) (see Fig. 4). However, ME express TLR not on their surface but rather inside the cell, and are only upregulated when the cell is infected.11 They also respond to microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (ie, butyrate) and many normal commensal microbial components, such as Bacteroides fragilis capsular polysaccharide A (see Fig. 4).12, 13 Unlike innate immune cells (ie, macrophages and neutrophils), which are proinflammatory and also first responders, ME respond with predominately an anti-inflammatory response. The normal response to TLR and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors like signaling is proinflammatory response through the nuclear factor-κB pathway. Metabolites, such as butyrate, and normal commensal components affect the mucous barrier by enhanced production of mucus by goblet cells. Their effect on ME results in increased production of AMPs, inhibition of nuclear factor-κB, and the production of the anti-inflammatory transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) by the ME.12, 13 The ME also express chemokines that are chemotactic and bind the chemokine receptor on mucosal system T cells. The production of chemokines by epithelial cells recruits these lymphocytes to the LP and into ME. These metabolites and normal commensal components also affect the immune response in the LP by increased production of sIgA by B cells; reduced expression of T cell–activating molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells (DCs); and increased number and function of regulatory T (Treg) cells and their production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β) and interleukin (IL)-10 (see Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).12, 13 The mucous barrier plus the immune regulatory function maintain tight junctions, blocking a major proinflammatory response while maintaining an anti-inflammatory environment that results in Treg cells (T cells that do not cause an inflammatory response), the production of IgA by the mucosal firewall results in homeostasis, the steady-state process where the function and integrity of the mucosa is maintained. Homeostasis is imperative for host survival. This process relies on a complex and coordinated set of barriers, innate and adaptive responses that selects and calibrates responses against self, food, commensals, and pathogens in the most appropriate manner. The interactions with commensals is key and is discussed later. ME have to integrate local cues, such as defined metabolites, cytokines, or hormones, allowing the induction of responses in a way that preserves the physiologic and functional requirements of each tissue (see Fig. 5). The regulatory pathways that are involved in the maintenance of a homeostatic relationship with the microbiota are tissue specific (see Fig. 4A).13 These same homeostatic processes also aid in repairing and limiting the damage in the face of inflammation (see Fig. 4B).13

A local increase of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 results in inhibition of the local proinflammatory response and increases eosinophils in the tissue. With only a proinflammatory response there is little resolution of disease and enhanced collateral damage and immunopathology.14 The proinflammatory/anti-inflammatory mucosal response increases with age and results in less disease. Neutrophils (eg, polymorphonuclear cells) die after a short time at sites of inflammation. Hydrolytic enzymes are released and contribute to the inflammatory response and tissue destruction contributing to collateral damage and enhanced disease. Neutrophil granule proteins induce adhesion and emigration of inflammatory monocytes to the site of inflammation. Neutrophils also create extracellular defenses by the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (see Fig. 6B).15, 16, 17 This neutrophil extracellular trap formation is induced by such agents as bacterial aggregates and biofilms, fungal hyphae, and protozoan parasites (cryptosporidia, Neospora, and coccidiosis) that cannot be phagocytized.18, 19, 20, 21 Neutrophils use the potent oxidative metabolism system to kill bacteria. This reaction is one of the most potent bactericidal mechanisms and is potentially fungicidal, parasiticidal, and viricidal. The eosinophil is capable of the same phagocytic and metabolic functions as the neutrophils but focuses the host’s defense against the tissue phase of parasitic infections. Basophils and mast cells have been associated primarily with allergic reactions because of their binding of IgE. They release inflammatory mediators necessary for the activation of the acquired immune response.22, 23 Alpha- and beta-interferon, the last component of this innate response, sets up an immediate wall against virus infections and also provides anti-inflammatory response. The second wave occurs a day or two later, when natural killer cells enhance AMP production,1, 5 kill parasites18, 19 and virally infected cells,24 but also produce cytokines to help the adaptive immune response.24

The adaptive phase occurs in the organized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT) (discussed later).25 MALT is the initial induction site for mucosal immunity for antigens that are sampled from mucosal surfaces. The DC are important because they are APC that help in discriminating between dietary antigens, commensal microflora, and pathogens, and interacting with T cells. Another T cell, Gamma delta T cells, are found in high levels in the mucosa and the LP in cattle have a unique role in ruminant immunology (discussed in Mariana Guerra-Maupome and colleagues’ article, “Gamma Delta T Cell Function in Ruminants,” elsewhere in this issue).

Microbiome and enteric immunity

The microbiome is essential for immune development in the neonatal calf and maintenance of health in the older animals. The microbiome-gut-immune-brain axis maintains the health of all animals.13, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 As the calf develops there is a succession of microbes that finally culminates in what is called a “climax” community that occurs as the GIT transitions to an anaerobic environment.29, 33 This succession is influenced by nutrition, stress, and environment. This microbial community of commensals and their metabolites control the health of the mucosa and the underlying immune cells in the LP (see Figs. 4 and 5).32, 34, 35 These commensal metabolites stimulate ME to produce TGF-β, which is essential for the development of Treg lymphocytes that produce anti-inflammatory IL-10 (see Figs. 4 and 5). The microbial components in the microbiome also stimulate ME to produce serum amyloid A, which stimulates DCs to activate another important mucosa Treg cell, TH17 cells (see Fig. 4).36 These microbial metabolites also directly stimulate a natural killer–like cell type 3 innate lymphoid cells to produce IL-22 to induce the enterocytes to produce more defensins (eg, REGIIIγ and REGIIIβ) (see Fig. 5). The composition of the microbiome varies by location with the numbers and diversity of populations being high in the rumen and increasing dramatically from the abomasum to the colon, with the ileum being a key organ for microbial-immune development. In URT, there are dramatic differences between the nasopharyngeal region and lung in numbers and diversity of populations.31, 37 These microbiome communities have evolved to help protect the animal by improving barrier and immune function; understanding the complexity of the microbial ecosystem is essential.38, 39

The stress of weaning, comingling, transportation, dietary changes, antimicrobial therapy, and abrupt diet changes results in major microbial population shifts in the luminal microbial ecosystem, the microbiome (see Fig. 7).26 This lowers the defenses against pathogen entry, leading to increased risk of disease. This leads to dysbiosis, the loss of good bacteria with an overgrowth of harmful organisms (see Fig. 8).35, 40 However, dysbiosis is not just the loss of microbiome, it results in depletion of the kill zone (see Fig. 2); the mucous layer becomes thinner and the amount of sIgA and AMP declines weakening the barrier, allowing pathogens to interact with the mucosa and cause disease. Commensal organisms that help stimulate the mucosa to be anti-inflammatory are no longer available so tight junctions become weakened, leaky gut occurs, and proinflammatory responses occur that further weaken the gut epithelium (see Figs. 6 and 9).30 One major factor leading to the dysbiosis and diarrhea that one can learn from pigs is low feed and water intake.41 Dysbiosis is also associated with susceptibility to Johne disease.40

Organized and diffuse mucosal lymphocytes

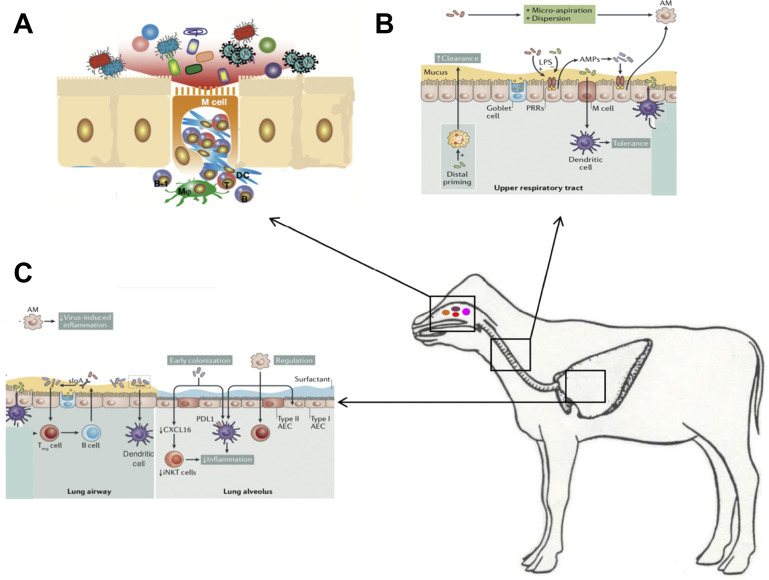

Organized MALT is widely distributed in mucosal surfaces throughout the body. MALT is the initial induction site for mucosal immunity for antigens that are sampled from mucosal surfaces and where the mucosal adaptive immune response develops. These mucosal aggregates or follicles (also known as lymphoid follicles [LF]) of B cells, T cells, and DCs and macrophages APCs are covered by epithelium that contains specialized epithelial cells called dome or M cells that are found in the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissues (BALT) (Fig. 10 ),42 gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) (Fig. 11 ),43 and in the uterus (Fig. 12 ).44 These dome cells pinocytose antigen and transport it across the ME (see Fig. 10A).45 The antigen may then be processed by APCs and presented to T and B lymphocytes; indeed, APCs play a central role in the induction and maintenance of mucosal immunity.46 The lymphocytes that emigrate from these LF into the surrounding LP are referred to as diffuse lymphocytes.47 The hallmark of this system is that local stimulation results in memory T and B cells in the nearby mucosal tissue but also in other mucosal tissues (Fig. 13 ).

Fig. 10.

Respiratory mucosal immune system. (A) The nasal associated lymphoid tissue including the tonsils is an important site for immune responses and microbiome interactions and respiratory pathogen carriage. Microfold cells (M cells) specialize in antigen uptake and are present throughout the respiratory and GI mucosal immune system. The cilia of M cells are shorter than those of conventional epithelium cells. These cells are like a window to the immune system and allow interaction with viruses, bacteria, and other components of the microbiome. On its basal side, the M cell develops a pocket-like structure that can hold immunocompetent cells. M cells, such as macrophages (MΦ), function in active antigen uptake. Because lysosome development in M cells is poor, in most cases the incorporated antigens are just passed through the M cells unmodified and then taken up by DCs, which then interact with T cells, which in turn interact with B cells. (B) URT and (C) lower respiratory tract (LRT). The URT mucous is thicker than the LRT and the ME are taller and decrease in size as one descends into the LRT and the alveoli. Resident microorganisms prime immune cells include ME, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, which all contribute to the clearance of pathogens. Moreover, microbial signaling is necessary for the recruitment and activation of regulatory cells, such as anti-inflammatory alveolar macrophages and Treg cells. The host responds to microbial colonization through the release of AMPs and sIgA. Sensing of the microbiota involves microfold (M) cells that activate tolerogenic dendritic cells. In addition, alveolar dendritic cells can directly sample luminal microorganisms. These pathways lead to the regulation of inflammation and the induction of tolerance in the respiratory tract. It is also likely that early bacterial colonization is key to long-term immune regulation, which is illustrated by the microbiota-induced decrease in CXC-16 (Cxcl16) gene, which prevents the accumulation of inducible natural killer T cells, and by the programmed death ligand 1–mediated induction of tolerogenic dendritic cells. This tolerant milieu, in turn, contributes to the normal development and maintenance of resident bacterial communities, which are also influenced by host and environmental factors. AEC, alveolar epithelial cell; AM, alveolar macrophages; iNKT, inducible natural killer T cells; PDL1, programmed death ligand 1; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; URT, upper respiratory tract.

(Adapted from Sato S, Kiyono H. The mucosal immune system of the respiratory tract. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(3):225-232 and Man WH, de Steenhuijsen Piters WAA, Bogaert D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-270; with permission.)

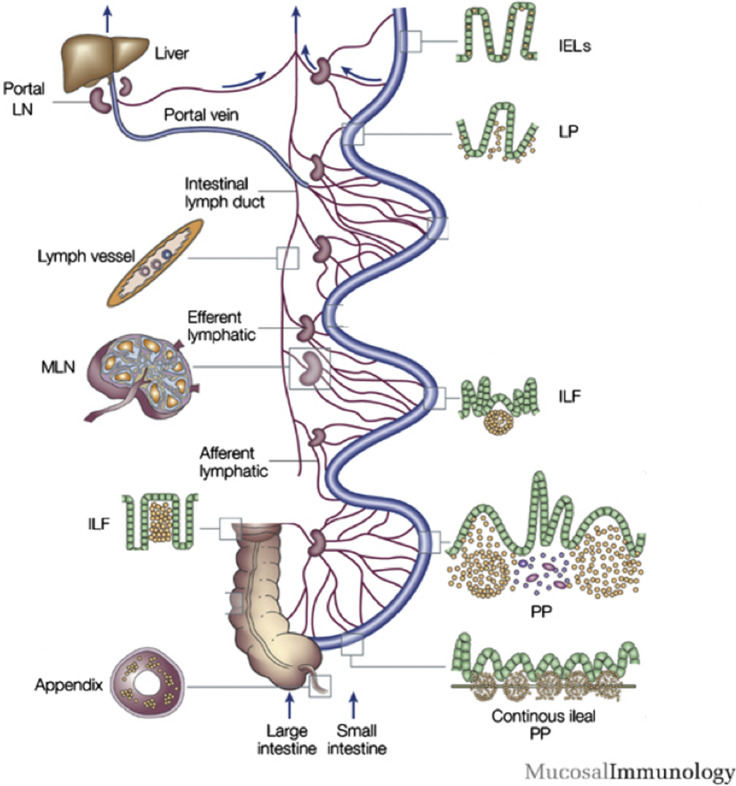

Fig. 11.

Gastrointestinal mucosal immune system. Lymphocytes can leave the surface epithelium (intraepithelial lymphocytes) or LP via draining afferent lymphatics to mesenteric lymph nodes, or via portal blood reaching the liver where induction of tolerance occurs. The M cells in the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyers patches (PPs) transport antigen to prime B cells in the isolated lymphoid follicles of the PPs of the jejunum, ileum, and the large intestine. The continuous ileal PP (IPP) are a primary lymphoid organ responsible for B-cell development. The IPP are up to 2 m long and constitute 80% to 90% of the intestinal lymphoid tissue. IEL, intraepithelial lymphocytes; ILF, isolated lymphoid follicles; LN, lymph node; MLN, mesenteric lymph nodes.

(Adapted from Brandtzaeg P, Kiyono H, Pabst R, Russell MW. Terminology: nomenclature of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(1):31-37; with permission.)

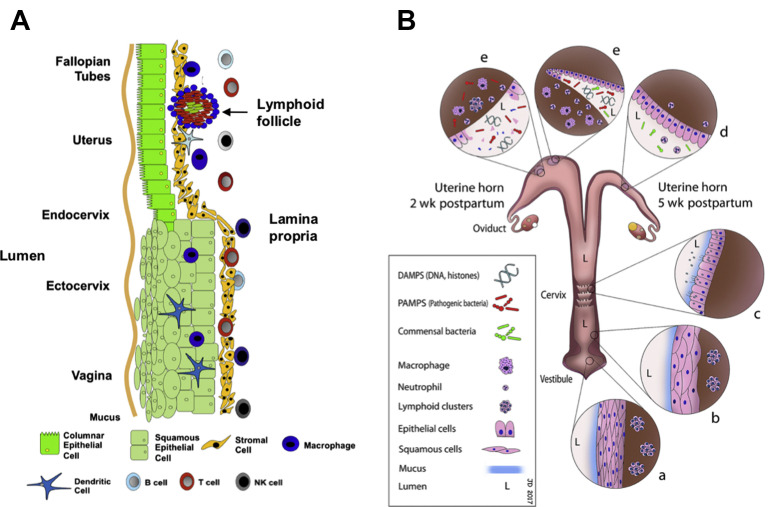

Fig. 12.

Reproductive mucosal immune system. (A) Schematic of the mucosal immune system throughout the nongravid female reproductive tract. The vagina and ectocervix are lined with squamous epithelial cells. Columnar mucosa epithelium is present throughout the upper female reproductive tract including the endocervix, uterine endometrium, and fallopian tubes. (B) Schematic of the mucosal immune system of postpartum female bovine reproductive tract. The vulvar opening acts as the portal for entry and clearance of microbial contaminants. Multiple epithelial layers in the vestibule (a) and vagina (b) prevent bacterial entry at these anatomic sites unless they have been breached because of laceration during delivery. The cervix (c), although still dilated after calving, provides another barrier to the entry of microbes into the uterus because of epithelial folding and secretion of mucus that flows outward to the vagina. Around the second week postpartum (e), the simple columnar uterine epithelial barrier is breached at the caruncles because of death of epithelial cells. For the next 3 weeks, the uterus responds to microbial contamination and colonization while re-establishing the integrity of the epithelial barrier (d).

(Adapted from Wira CR, Fahey JV, Rodriguez-Garcia M, et al. Regulation of mucosal immunity in the female reproductive tract: the role of sex hormones in immune protection against sexually transmitted pathogens. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(2):236-258 and from Dadarwal D, Palmer C, Griebel P. Mucosal immunity of the postpartum bovine genital tract. Theriogenology. 2017;104:62-71; with permission.)

Fig. 13.

Lymphocyte circulation and common mucosal immune system of the bovine. As illustrated on the left side of the figure, lymphocyte circulation with lymphocytes entering the lymph nodes by afferent lymphatics and exiting by efferent lymphatics. The common mucosal system involves the circulation of B and T cells between lymphoid tissues on mucosal surfaces.

Respiratory mucosal immune system

The respiratory mucosal immune system contains a large number of lymphocytes. Unlike the GI mucosal immune system, sIgG is an important mucosal defense mechanism of the nasopharyngeal associated lymphoid tissue (NALT). The NALT ME varies from squamous to more columnar ME in the tonsillar regions.28 NALT contains organized LF making it an optimal target for mucosal vaccines (Fig. 14 ).28, 42 The NALT microbiome contains commensals along with several possible pathogens including Mycoplasma bovis, Mannheimia haemolytica, Histophilus somni, and Pasteurella multicida.28, 37 The NALT, like the GALT and BALT, contains M cells (see Fig. 10A) that provide easy access for antigens to the immune system and induction of adaptive immune responses.45 The URT is lined by ciliated ME cells and has a major role in clearance of particulates via the mucociliary escalator (see Fig. 10B).48 The URT ME maintains the kill zone (see Fig. 10B).48 The URT ME also regulate the anti-inflammatory response in the LP. The URT also contains BALT that are active in the production of IgA and in tolerance against normal respiratory microbiome. The microbiome is less complex in the URT and contains fewer organisms than the NALT.28, 31, 48 The lower respiratory tract (LRT) contains the larger bronchial airways and the alveoli. ME in LRT are shorter and have the same functions as the ME of the URT (see Fig. 10C). In the alveoli, the mucous has been replaced by surfactant and the primary function of ME and the alveolar macrophages is to minimize inflammation (see Fig. 10C). The microbiome in the LRT is less complex than URT and contains fewer organisms. In healthy animals, there should be no microorganisms in the alveoli (see Fig. 10C).48

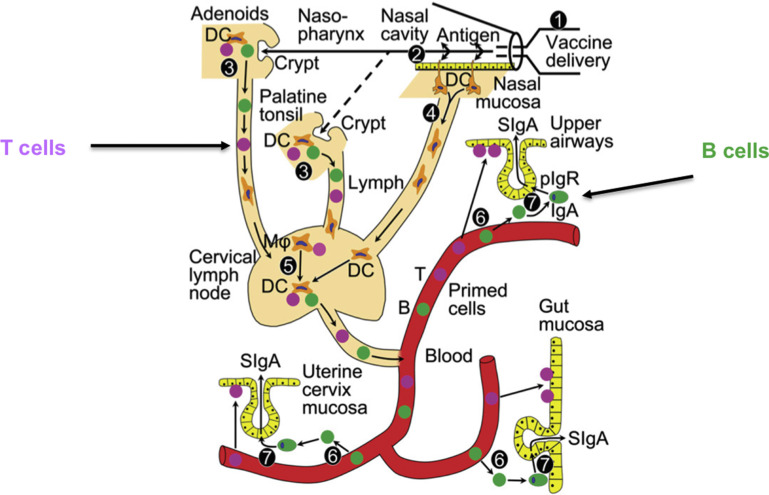

Fig. 14.

Induction immunity after nasal vaccine administration. (1) Delivery of nasal vaccine. (2) Uptake of vaccine antigen through nasal mucosa. (3) Immune induction in nasal-associated lymphoid tissue including tonsils. (4) Antigen targeting and migration of mucosal DCs to regional lymph node. (5) Immune induction and amplification in regional (cervical) lymph nodes by antigen-loaded DCs and macrophages (MΦ). (6) Compartmentalized homing and exit of nasal-associated lymphoid tissue–induced T and B cells to secretory effector sites in airways, gut, and uterine cervix. (7) Local production and pIgR-mediated external transport of dimeric IgA to generate sIgA.

(Adapted from Brandtzaeg P. Potential of nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue for vaccine responses in the airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(12):1595-1604; with permission.)

Gastrointestinal tract mucosal immune system

The GI mucosal immune system alone contains more than a trillion (1012) lymphocytes and has a greater concentration of antibodies than other tissue in the body. Mucous varies in depth and character throughout the length of the GIT with less viscous mucous being present in the upper GIT and a more viscous mucous in the lower GIT. The GI mucosal lymphoid organ system begins developing at 100 days of gestation when the mesenteric lymph nodes are present (see Fig. 11).25, 43 The jejunum contains the discrete Peyer patches and the continuous ileal Peyer patches (IPP) (see Fig. 11). There are also discrete LF distributed throughout the GIT; these are less developed than the Peyer patches and are often temporary as the result of a local immune response. IPP play a continual role in immune development particularly of B lymphocytes. The B lymphocytes present are almost exclusively IgM+ cells and if the IPP are removed, the animals remain deficient in B cells for at least 1 year because the IPP is the major source of the peripheral B-cell pool. Because the IPP is the site of proliferation and negative selection, IPP follicles are inferred as the major site49 for generation of the preimmune B-cell repertoire in ruminants,50 whereas the discreet Peyer patches, distributed throughout the jejunum, function as induction sites for the generation of IgA plasma cells (see Fig. 11).50 Unfortunately, the role of the rumen in mucosal immunity is unclear.

Female reproductive mucosal immune system

The female reproductive tract (FRT) is a dynamic immune system because of the cyclicity of hormonal regulation and pregnancy (see Fig. 12). The thickness and character of mucous varies by the anatomic location in the reproductive tract and time of the reproductive cycle. There are elevated levels of IgG and IgA in cervicovaginal mucus, and IgA, IgE, and IgG in the uterus. sIgG is an important mucosal defense mechanism for the FRT.7 Only the endocervix and uterus has the columnar ME and these cells are sloughed and repopulated during normal estrus cycle (see Fig. 12A).44 Following delivery of a calf, the FRT undergoes an active inflammatory process to clear cellular debris from the placenta and respond to bacterial contamination. The ME cells of the uterus completely slough. In healthy cows, uterine inflammation subsides by the fourth to fifth week postpartum. However, FRT (mainly of the uterus) repair is not complete until the sixth to eighth week postpartum (see Fig. 12B).27 The normal uterine ME are leakier than the GIT and URT. The LP of a healthy reproductive tract normally has fewer innate and adaptive cells with a few LF (see Fig. 12A). Following calving, activation of the innate immune system is essential for placental separation. During the first week postpartum, there is increased influx of neutrophils recruitment following normal parturition and this neutrophil recruitment is closely associated with increased cytokine secretion seen in clinically normal cows until 24 days in milk.51 Neutrophil levels decline by the fourth week postpartum when uterine involution is almost complete. Macrophages also provide a crucial component in phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and regulation of uterine inflammation. Once bacteria have been cleared, anti-inflammatory macrophages are present to aid in uterine involution. Isolated LF are found throughout the bovine genital tract (see Fig. 12). The LF located in the LP are believed to be immune induction sites because they have been observed following infection with bovine genital tract pathogens. T cells and B cells are also present in the lumen. Microflora of the FRT depend on fertility and parturition status of the animal. In the healthy FRT, the microbial flora are a combination of aerobic, facultatively anaerobic, and obligately anaerobic microorganisms.52 Following parturition, bacterial contamination of the uterus occurs for 2 to 3 weeks postpartum because of calving-associated relaxation of physical barriers, including an open cervix. Negative pressure events created by repeated uterine contraction and relaxation enhances bacterial contamination by a vacuum effect. Gram-negative bacteria predominate in bovine uteri during the first week after calving and are gradually replaced by gram-positive bacteria during the second and third week postpartum. Bacterial contamination is cleared in most cows by the end of the fourth week postpartum.27

Common mucosal system

Lymphocytes are divided into two populations: those that circulate between the bloodstream and the systemic lymphoid tissues, and those that circulate between the bloodstream and lymphoid tissues associated with mucosal surfaces. In the MALT, mature T cells and B cells that have been stimulated by antigen and induced to switch to produce IgA leave the submucosal lymphoid tissue and reenter the bloodstream (see Fig. 13).42, 43 These lymphocytes exit the bloodstream through high endothelial venule and locate in the LP (see Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12). B cells differentiate into plasma cells that secrete dimeric IgA. Many of these cells return to the same mucosal surface from which they originated but others are found at different mucosal surfaces throughout the body. This homing of lymphocytes to other MALT sites throughout the body is referred to as the “common immune system” (see Fig. 13). For example, oral immunization can result in the migration of IgA precursor cells to the bronchi and subsequent secretion of IgA onto the bronchial mucosa. There is a special affinity for lymphocytes, which have been sensitized in the gut to migrate to the mammary gland to become plasma cells and secrete IgA into the milk.

Mucosal vaccine responses

Protecting the animal from infection at mucosal surfaces, such as the GIT, respiratory tract, mammary glands, and FRT, is especially difficult for the systemic immune system. The antibodies responsible for humoral immunity and lymphocytes responsible for cell-mediated immunity are predominantly in the bloodstream and tissues; they are typically not found on the mucosal surfaces. Therefore, although lymphocytes assist in preventing systemic invasion through the mucosal surface, they are often not effective at controlling infection on the mucosal surface. Even in the lungs and the mammary gland, where IgG and lymphocytes are found in relative abundance, they are not able to function as effectively in mucosal tissues. Adaptive immune protection on mucosal surfaces is caused in large part by sIgA, cytotoxic T cells, and γδ T cells. The route of vaccine administration is important when attempting to induce mucosal immunity. To induce sIgA production at mucosal surfaces, it is best for the vaccine to enter the body via a mucosal surface. This is accomplished by administering the vaccine to mucosal surfaces by aerosolizing the vaccine so the animal inhales it (intranasal vaccination) or by feeding the vaccine to the animal (oral vaccination). Parenteral vaccines can generate mucosal responses that produce mucosal sIgA.53 Work in our laboratory has demonstrated mucosal immunity following parenteral vaccination in the face of maternal immunity, which generated bovine respiratory syncytial virus–specific mucosal IgA that protected against bovine respiratory syncytial virus disease.54

Intranasal vaccines have been used because of the high concentration of lymphoid tissue in the NALT,42 the induction of a rapid interferon response,55 the induction of immunity against bovine respiratory disease pathogens,28 and the lack of interference from maternal antibodies.56 Induction of the NALT also has implications for induction of other mucosal sites as a result of the common mucosal response (see Figs. 13 and 14).28, 42

The main portal of entry for oral vaccines is the lymphoid tissue in the NALT. Timing seems to be critical for immunization of GALT, like Peyers patches in the GIT. Administration of modified live virus vaccine within the first 24 hours after birth would be at risk of neutralization and inactivation by the colostral maternal antibody. Numerous studies have shown that rotavirus-coronavirus modified live virus vaccines studies fail to protect in the presence of maternal antibodies (Geoff Smith, personal communication, 2018). Once animals are 1 to 2 days of age or older, the harsh pH and proteolytic environment of GIT affect antigenicity of vaccines intended to induce GALT.

Summary

The mucosal immune system provides the first immune defense barrier. The health of the ME, is important not only for the growth and development of cattle, through secretion and absorption in the GIT, oxygen exchange and particulate removal in the respiratory tract, and fetal development in the FRT, but also provides the first immune response to microorganisms. The ME maintain a kill zone barrier to keep out pathogens in concert with the commensal microorganisms (microbiome) and other cells of the immune system. The microbiome functions best when it is in a stable condition resulting in immune homeostasis. Immunoregulation by the ME and microbiome results in the establishment of a mucosal firewall. Disruptions in the microbiome results in dysbiosis, which decreases the kill zone, allows leaky gut, and increases inflammation. This increased inflammation is seen as an important part of pathogenesis of infectious diseases of the GIT, respiratory, and reproductive tract. Delivery of vaccines to enhance mucosal immunity is a key strategy to protect animal health particularly with the decreased use of antibiotics. Maintaining the mucosal firewall and inducing mucosal immunity through vaccination are keys to maintaining animal health, increasing animal productivity, and reducing antimicrobial usage.

References

- 1.Maynard C.L., Elson C.O., Hatton R.D., et al. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelaseyed T., Bergström J.H., Gustafsson J.K., et al. The mucus and mucins of the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2014;260:8–20. doi: 10.1111/imr.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanin M., Baviskar P., Webster R., et al. The interaction between respiratory pathogens and mucus. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson M.E.V., Hansson G.C. Is the intestinal goblet cell a major immune cell? Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:251–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maldonado-Contreras A.L., McCormick B.A. Intestinal epithelial cells and their role in innate mucosal immunity. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L.-J., Gallo R.L. Antimicrobial peptides. Curr Biol. 2016;26:R14–R19. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horton R.E., Vidarsson G. Antibodies and their receptors: different potential roles in mucosal defense. Front Immunol. 2013;4:200. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchiando A.M., Graham W.V., Turner J.R. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvidera S.K., Dickson M.J., Abuajamieh M., et al. Intentionally induced intestinal barrier dysfunction causes inflammation, affects metabolism, and reduces productivity in lactating Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:4113–4127. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villena J J., Aso H., Rutten V.P.M.G., et al. Immunobiotics for the bovine host: their interaction with intestinal epithelial cells and their effect on antiviral immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:326. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katwal P., Thomas M., Uprety T., et al. Development and biochemical and immunological characterization of early passage and immortalized bovine intestinal epithelial cell lines from the ileum of a young calf. Cytotechnology. 2019;71:127–148. doi: 10.1007/s10616-018-0272-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troy E.B., Kasper D.L. Beneficial effects of Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharides on the immune system. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2010;15:25–34. doi: 10.2741/3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkaid Y., Hand T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angus K.W., Tzipori S., Gray E.W. Intestinal lesions in specific-pathogen-free lambs associated with a cryptosporidium from calves with diarrhea. Vet Pathol. 1982;19:67–78. doi: 10.1177/030098588201900110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi S.D., Malachowa N., Deleo F.R. Influence of microbes on neutrophil life and death. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:159. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Buhr N., Reuner F., Neumann A., et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation in the Streptococcus suis-infected cerebrospinal fluid compartment. Cellular Microbiology. 2017;19(2):e12649. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branzk N., Lubojemska A., Hardison S.E., et al. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald V., Korbel D.S., Barakat F.M., et al. Innate immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Parasite Immunol. 2013;35:55–64. doi: 10.1111/pim.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitch G.J., He Q. Cryptosporidiosis: an overview. J Biomed Res. 2012;25:1–16. doi: 10.1016/S1674-8301(11)60001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruns S., Kniemeyer O., Hasenberg M., et al. Production of extracellular traps against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in infected lung tissue is dependent on invading neutrophils and influenced by hydrophobin RodA. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000873. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behrendt J.H., Ruiz A., Zahner H., et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation as innate immune reactions against the apicomplexan parasite Eimeria bovis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010;133:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham S.N., St John A.L. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:440–452. doi: 10.1038/nri2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galli S.J., Tsai M. Mast cells in allergy and infection: versatile effector and regulatory cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1843–1851. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shekhar S., Yang X. Natural killer cells in host defense against veterinary pathogens. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2015;168:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebler-Tenorio E.M., Pabst R. MALT structure and function in farm animals. Vet Res. 2006;37:257–280. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeineldin M., Lowe J., Aldridge B. Contribution of the mucosal microbiota to bovine respiratory health. Trends Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dadarwal D., Palmer C., Griebel P. Mucosal immunity of the postpartum bovine genital tract. Theriogenology. 2017;104:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osman R., Malmuthuge N., González-Cano P., et al. Development and function of the mucosal immune system in the upper respiratory tract of neonatal calves. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2018;6:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-030117-014611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmuthuge N., Guan L.L. Understanding the gut microbiome of dairy calves: opportunities to improve early-life gut health. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:1–10. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura R., Takeda K. Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e338. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timsit E., Workentine M., van der Meer F., et al. Distinct bacterial metacommunities inhabit the upper and lower respiratory tracts of healthy feedlot cattle and those diagnosed with bronchopneumonia. Vet Microbiol. 2018;221:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taschuk R., Griebel P.J. Commensal microbiome effects on mucosal immune system development in the ruminant gastrointestinal tract. Anim Health Res Rev. 2012;13:129–141. doi: 10.1017/S1466252312000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malmuthuge N., Guan L.L. Gut microbiome and omics: a new definition to ruminant production and health. Animal Frontiers. 2016;6(2):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y.H., Nagata R., Ohtani N., et al. Effects of dietary forage and calf starter diet on Ruminal pH and bacteria in Holstein calves during weaning transition. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1575. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khosravi A., Mazmanian S.K. Disruption of the gut microbiome as a risk factor for microbial infections. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D., Yoo S.-A., Kim W.-U. Gut microbiota in autoimmunity: potential for clinical applications. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39:1565–1576. doi: 10.1007/s12272-016-0796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timsit E., Holman D.B., Hallewell J., et al. The nasopharyngeal microbiota in feedlot cattle and its role in respiratory health. Anim Front. 2016;6:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer E.A., Tillisch K., Gupta A. Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:926–938. doi: 10.1172/JCI76304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez D.E., Arroyo L.G., Costa M.C., et al. Characterization of the fecal bacterial microbiota of healthy and diarrheic dairy calves. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31:928–939. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derakhshani H., De Buck J., Mortier R., et al. The features of fecal and ileal mucosa-associated microbiota in dairy calves during early infection with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:426. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fouhse J.M., Zijlstra R.T., Willing B.P. The role of gut microbiota in the health and disease of pigs. Animal Frontiers. 2016;6(3):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandtzaeg P. Potential of nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue for vaccine responses in the airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1595–1604. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1783OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brandtzaeg P., Kiyono H., Pabst R., et al. Terminology: nomenclature of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:31–37. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wira C.R., Fahey J.V., Rodriguez-Garcia M., et al. Regulation of mucosal immunity in the female reproductive tract: the role of sex hormones in immune protection against sexually transmitted pathogens. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72:236–258. doi: 10.1111/aji.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato S., Kiyono H. The mucosal immune system of the respiratory tract. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inman C.F., Haverson K., Konstantinov S.R., et al. Rearing environment affects development of the immune system in neonates. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brandtzaeg P. 'ABC' of mucosal immunology. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2009;64:23–38. doi: 10.1159/000235781. [discussion: 38–43, 251–7] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Man W.H., de Steenhuijsen Piters W.A.A., Bogaert D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butler J.E. Immunoglobulin diversity, B-cell and antibody repertoire development in large farm animals. Rev Off Int Epizoot. 1998;17:43–70. doi: 10.20506/rst.17.1.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang G., Malmuthuge N., Bao H., et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals regional and temporal differences in mucosal immune system development in the small intestine of neonatal calves. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:602. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2957-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabler C., Fischer C., Drillich M., et al. Time-dependent mRNA expression of selected pro-inflammatory factors in the endometrium of primiparous cows postpartum. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:152. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y., Ametaj B.N., Ambrose D.J., et al. Characterisation of the bacterial microbiota of the vagina of dairy cows and isolation of pediocin-producing Pediococcus acidilactici. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su F., Patel G.B., Hu S., et al. Induction of mucosal immunity through systemic immunization: phantom or reality? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1070–1079. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1114195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolb et al. Protection against bovine respiratory syncytial virus in calves vaccinated with adjuvanted modified live vaccine administered in the face of maternal antibody. Vaccine, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Todd J.D., Volenec F.J., Paton I.M. Interferon in nasal secretions and sera of calves after intranasal administration of avirulent infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus: association of interferon in nasal secretions with early resistance to challenge with virulent virus. Infect Immun. 1972;5:699–706. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.699-706.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vangeel I., Antonis A.F., Fluess M., et al. Efficacy of a modified live intranasal bovine respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in 3-week-old calves experimentally challenged with BRSV. Vet J. 2007;174:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]