Highlights

-

•

We identify two SNPs and two variation sites in human IFITM1.

-

•

The expression level of IFITM1 mRNA is stable in the human digestive system.

-

•

The IFITM1 promoter SNP is associated with the transcriptional level of IFITM1.

-

•

The IFITM1 might be a candidate gene associated with the pathogenesis of UC.

Keywords: IFITM1, CD225, IBD, Ulcerative colitis, Polymorphism

Abstract

Interferon inducible transmembrane protein (IFITM) family genes have been implicated in several cellular processes such as the homotypic cell adhesion functions of IFNs and cellular anti-proliferative activities. We previously showed that the IFITM3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with susceptibility to ulcerative colitis (UC). The present study aimed to investigate whether the polymorphisms in the IFITM1 gene are associated with susceptibility to UC. We also evaluated the expression levels in the putative functional promoter polymorphisms to determine the change of their activity. Gene expression profiles in the tissues obtained from human digestive tracts by RT-PCR, and the possible variation sites and SNPs of IFITM1 were identified by direct sequencing method. Genotype analysis in the IFITM1 SNPs was performed by high resolution melting and TaqMan probe analysis, and the haplotype frequencies of IFITM1 SNPs for multiple loci were estimated using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. The expression levels in the putative functional promoter polymorphisms were evaluated by performing a luciferase reporter assay. We identified two SNPs and two variation sites, g.-1920G>A (rs77537847), g.-1547delA (novel) and g.-416C>G (rs11246062) in the promoter region, and g.364delA (rs200576757) in intron 1. The genotype and allele frequencies of the g.-1920G>A polymorphism of IFITM1 gene in the UC patients were significantly different from those of the healthy controls (P = 0.002 and 0.042, respectively). These results suggest that the g.-1920G>A polymorphism in IFITM1 may be associated with susceptibility to UC.

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) belong to the group of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract of unknown etiology [1]. IBDs are complex and multifactorial involving genetic, environmental and microbial factors [2], [3]. The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted by T cells is responsible for both initiation and perpetuation of IBD. Cytokine production in lamina propria CD4+ T lymphocytes differs between CD and UC. Whereas CD is associated with increased production of T helper 1 cell (Th1) type cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), UC is associated with T cells that produce large amounts of the Th2 type cytokine IL-5, however, IFN-γ production is not affected [4], [5], [6]. Th1 and Th2 cells cross-regulate one another in their differentiation.

Interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1, also known as CD225, 9–27 or LEU13) is a member of the IFITM protein family, which mediates cellular processes, including the homotypic cell adhesion functions of IFNs. Expression levels of IFITM genes have been found to be up-regulated in gastric cancer cell and colorectal tumors [7], [8]. The IFITM family potently inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) [9], SARS coronavirus [10], West Nile virus and dengue virus infections [11]. IFITM1 was initially cloned from a human lymphoid cell cDNA library [12], and is located on chromosome 11p15.5 [13]. IFITM1 proteins play separate roles in mouse primordial germ cell homing and repulsion [14], and also play an essential role in the anti-proliferative action of IFN-γ [15].

We have previously identified 7 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and multiple variation regions in the IFITM3 gene, another member of the IFITM family, and have suggested that IFITM3 polymorphisms are associated with a susceptibility to UC [16]. However, other IFITM family including the IFITM1 gene in the epipathogenesis of UC has not been elucidated. In an attempt to understand the genetic influences of IFITM1 on UC, we have identified possible variation sites and SNPs through the two exons of IFITM1 and their boundary intron sequences, including the ∼2.2 kb promoter regions. To determine whether or not these IFITM1 SNPs are associated with susceptibility to UC, genotype and allele frequencies of IFITM1 polymorphisms were analyzed on genomic DNAs isolated from UC patients and healthy controls. Furthermore, we investigated haplotype frequencies constructed by these SNPs in both groups. We also evaluated the expression levels in the putative functional promoter polymorphisms by performing a luciferase reporter assay to determine the change of their activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and DNA samples

The DNA samples used in this study were provided by the Biobank of Wonkwang University Hospital, a member of the National Biobank of Korea, which is supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare Affairs. On the basis of approval and informed consent from the institutional review board, we obtained the genomic DNAs from 126 UC patients (70 males and 56 females) and 529 healthy controls (332 males and 197 females). Mean ages of IBD patients and controls were 41.3 years and 40.8 years, respectively. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes by using a standard phenol-chloroform method or by using a Genomic DNA Extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea) according to the manufacturer's directions. IBD patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic at Wonkwang University Hospital. Patients were classified into the IBD group according to clinical features, endoscopic findings, and histopathologic examinations. Healthy controls were recruited from the general population, and had received comprehensive medical testing at the Wonkwang University Hospital. All subjects in this study were Korean.

2.2. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequence analysis

The entire coding regions of the IFITM1 gene, including the ∼2.2 kb promoter regions, were partially amplified by PCR using the two primer pairs (Table 1 ). PCR reactions were prepared by previously described procedures [17]. Amplification was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 thermocycler (PE Applied Biosystem, USA) at 95 °C for 5 min in order to pre-denature the template DNA, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 68 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 2.0 or 2.5 min. The final extension was completed at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products purified by use of a PCR purification kit (Millipore, USA) were used template DNA for sequencing analysis. Purified PCR products were sequenced using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing system (PE Applied Biosystems, USA) on the ABI 3100 automatic sequencer (PE Applied Biosystem). Both sense and antisense strands of PCR products were directly sequenced using the same primers used for the PCR amplification, and seven primers were additionally used to sequence the promoter and intron 1 region (Table 1). SNPs and variation sites of the IFITM1 gene were detected by direct sequence analysis. The reference sequence for the IFITM1 gene was based on the sequence of human chromosome 11, clone RP13-317D12.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for PCR amplification, sequencing analysis and genotyping in this study.

| Applications | Primers | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR analysis | IFITM1-PF1 | ATCCTCCAGCCGCGTGACTCCT | Promoter and exon 1 |

| IFITM1-PR1 | ACACAAGTCCCCACCCCAGGCA | ||

| IFITM1-PF2 | TGCGACAAGTGAGGTGAGGGCT | Exon 1, 2 and intron 1 | |

| IFITM1-PR2 | AGAGGAGGGATACGGCTGTGCA | ||

| Sequencing analysis | IFITM1-SF1 | TCAGGTAGGAAGGGGGCTTG | Promoter |

| IFITM1-SF2 | TCCTCGATGTCTCAGAGCACGCT | Promoter | |

| IFITM1-SF3 | ACATGAACGTGAAAAGCATTTAGGCT | Promoter | |

| IFITM1-SF4 | ACCCTCCAGGTCTCTCCTGCAT | Promoter | |

| IFITM1-SR1 | AGCCTAAATGCTTTTCACGTTCATGTGA | Promoter | |

| IFITM1-SR2 | AGCCGCGTGCTATGGCTCCGT | Intron 1 | |

| IFITM1-SR3 | TGTCTCAGGACTAGGCCGGGA | Exon 2 | |

| TaqMan analysis | IFITM1-TF1 | TGCAAAGGTGGTTTCAGTTCCAT | g.-1920G>A |

| IFITM1-TR1 | AGAAACTGCAGGGCACAAGA | ||

| IFITM1-TVI1 | TCAGAATCCTATCTCCC | ||

| IFITM1-TFA1 | CAGAATCCTGTCTCCC | ||

| PCR-RFLP | IFITM1-RF1 | CTTATTAAAGATTCTACTTA | g.-1275C>T |

| IFITM1-RR1 | GCTCTGATTTTTCCTTTATG | ||

| High resolution melt (HRM) | IFITM1-HF1 | ACCCGCACAGAGCAGGACTGCA | g.-416C>G |

| IFITM1-HR1 | TCTGTCCACCCCAGGCCAGCA | ||

| RT-PCR | IFITM1-MF1 | TGAACTGGTGCTGTCTGGGCT | mRNA |

| IFITM1-MR1 | AGAGCCGAATACCAGTGACAGGA | ||

| Luciferase assay | IFITM1-LF1 | CAGGGTACCTCTCTCCAGATTAGTTTAGGC | Promoter |

| IFITM1-LR1 | CAGCTCGAGGGTTTGAGAAGTGTGGTTTTC | ||

2.3. mRNA expression level

The expression level of IFITM1 mRNA in various tissues was determined using MTC multiple tissue cDNA panels (Clontech, CA, USA), and IFITM1-MF1 and IFITM1-MR1 primers were used for RT-PCR (Table 1). The image of RT-PCR was analyzed using ImageJ 1.4 (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

2.4. Genotype analysis by TaqMan probe

The assay reagents for g.-1920G>A (rs77537847) in the IFITM1 gene was designed by Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems, USA). The reagents consisted of a 40X mix of un-labeled PCR primer and TaqMan MGB probes were labeled with the FAM dye and the other with the fluorescent VIC dye [18]. The reaction in 10 μl was optimized to work with 0.125 μl 40× reagents, 5 μl 2× TaqMan Genotyping Master mix (Applied Biosystems, USA), and 2 μl (50 ng) of genomic DNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle at 95°C for 15 min; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 45 s. The PCR was performed in the Rotor-Gene thermal cycler RG6000 (Corbett Research, Australia). The samples were read and analyzed by using the Rotor-Gene 1.7.40 software (Corbett Research, Australia).

2.5. Genotype analysis by high-resolution melting analysis

Genotype analysis was performed by high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis for the g.-416C>G (rs1124662) in the IFITM1 gene. The 10 μl reaction mixture comprised 2 μl of genomic DNA (50 ng), 1 μl of primer mix (containing 5 pmol of the forward and reverse primers), 0.25 μl of EvaGreen solution (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) and 5 μl of a QuantiTect Probe PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). PCR cycling and HRM analysis were performed on the Gene™ 6000 (Corbett Research). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 15 min; 45 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s; annealing conditions at 60 °C for 10 s; and 72 °C for 30 s. After a completion of 45 cycles, melting curve data were generated by increasing the temperature from 77 to 95 °C at 0.1 °C/s and recording fluorescence. HRM curve analysis was performed using the Rotor-Gene 1.7.40 software and the HRM algorithm that was provided.

2.6. Luciferase assay

The promoter region of the human IFITM1 gene carrying either the g.-1920G or g.-1920A allele was inserted upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the pGL3 basic plasmid vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and this was verified by DNA sequencing. To make these constructs, we amplified the target sequence by PCR using a forward primer with KpnI and a reverse primer with XhoI (Table 1). These promoter plasmids were co-transfected into the SW480 cells (ATCC, USA) with a pRL-TK control vector (Promega), using Lipofectamin 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assays for firefly luciferase activity and Renilla luciferase activity were performed 24 h after the transfection of the cells using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) with a microplate luminometer LB 96V (BERTHOLD, Australia). To normalize the transfection efficiency, the luminescence value of the pGL3-basic vector was standardized with the value of the pRL-TK vector. Each experiment was repeated three times, and each sample was studied in triplicate.

2.7. Statistic analysis

UC patients and healthy control groups were compared using case–control association analysis. The χ 2 test was used to estimate Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Allele frequency was defined as the percentage of individuals carrying the allele among the total number of individuals. Logistic regression analyses were used to calculate odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for SNP sites. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analyses by pair-wise comparison of biallelic loci and haplotype frequencies of the IFITM1 gene for multiple loci were estimated using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm with SNPAlyze software (DYNACOM, Japan). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered an indication of statistical significance.

3. Results

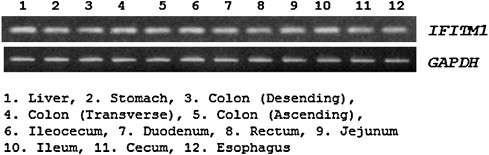

We examined expression patterns of IFITM1 mRNA in the various tissues of the human digestive system (Fig. 1 ). Our results showed that the expression level of IFITM1 mRNA was somewhat higher in tissues of the ileocecum than those in other tissues of the digestive system (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the expression level of IFITM1 gene is stable in normal digestive system.

Fig. 1.

Expression patterns of the IFITM1 mRNA by RT-PCR in the tissues of human digestive system.

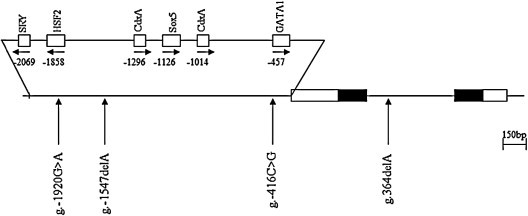

To determine the possible variation sites, in the entire coding regions, and the boundary intron sequences of IFITM1 that include about 2.2 kb of the promoter region, we scanned the genomic DNAs isolated from 24 unrelated UC patients and 24 healthy controls. We identified two SNPs and two variation sites by direct sequencing methods, g.-1920G>A (rs77537847), g.-1547delA (novel) and g.-416C>G (rs11246062) in the promoter region, and g.364delA (rs200576757) in intron 1 (Fig. 2 ). The LD coefficients (|D′|) between all SNP pairs were calculated, and there was no absolute LD (|D′| = 1 and r 2 = 1) among the SNPs of the IFITM1 gene (data not shown). Among the identified polymorphisms, two SNPs (g.-1920G>A and g.-416C>G) were selected for large sample genotyping. The SNP, g.-1275C>T (rs79441268, but not detected in our study), from the NCBI SNP database, was also genotype analyzed by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis. However, when 192 samples were analyzed, there was only a genotype. These results indicate that the g.-1275C>T (rs79441268) of IFITM1 might be a very rare polymorphism or monomorphism in the Korean population.

Fig. 2.

Locations of each single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and variation sites in IFITM1. Coding exons are marked by black blocks and 5′- and 3′-UTR by white blocks. The positions of SNPs were calculated from the translation start site. Putative transcription factor sites were searched at http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html. The reference sequence for IFITM1 was based on the sequence of human chromosome 11, clone RP13-317D12.

To determine whether the IFITM1 SNPs identified are associated with UC susceptibility, the genotypes of the IFITM1 polymorphisms were analyzed by the HRM or TaqMan probe method, and the genotype and allelic frequencies between the groups were compared. Although the genotype and allelic frequencies of the IFITM1 g.-416C>G in the UC patient group were not significantly different from those of the healthy control group, the genotype and allelic frequencies of the IFITM1 g.-1920G>A between the UC patients group and the healthy controls group were significantly different (Table 2 , P = 0.002 and 0.04, respectively). These results suggest that the g.-1920G>A identified in IFITM1 appear to be associated with UC susceptibility. To determine the possible correlation between the haplotypes associated with g.-1920G>A and g.-416C>G of the IFITM1 gene and UC susceptibility, we further analyzed haplotype frequencies of the SNPs in the UC patients and the healthy controls (Table 3 ). While the major (AC) haplotypes explaining more than 62.1% of the distributions were identified in the healthy controls, the AC haplotypes (57.8%), out of four possible haplotypes, were identified in the UC patients. However there are no significant differences between the groups (P = 0.239). These results suggest that the haplotype frequency of IFITM1 polymorphisms might be not associated with UC susceptibility.

Table 2.

Genotype and allele analyses of the IFITM1 gene polymorphisms in the UC patients and the healthy controls.

| Positiona | Genotype/allele | Control n (%) |

UC n (%) |

Odds ratiob (95% CI) | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g.-1920G>A (rs77537847) | AA | 198 (38.8) | 46 (36.8) | 1.00 | 0.002 |

| AG | 248 (48.6) | 48 (38.4) | 0.83 (0.53–1.30) | ||

| GG | 64 (12.5) | 31 (24.8) | 2.09 (1.22–3.56) | ||

| A | 644 (63.1) | 140 (56.0) | 1.00 | 0.04 | |

| G | 376 (36.9) | 110 (44.0) | 1.35 (1.02–1.78) | ||

| g.-416C>G (rs11246062) | CC | 322 (64.1) | 69 (59.5) | 1.00 | 0.35 |

| CG | 180 (35.9) | 47 (40.5) | 1.22 (0.81–1.84) | ||

| GG | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | ||

| C | 824 (82.1) | 185 (79.7) | 1.00 | 0.40 | |

| G | 180 (17.9) | 47 (20.3) | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | ||

Calculated from the translation start site.

Logistic regression analyses were used for calculating OR (95% CI; confidence interval).

Value was determined by Fisher's exact test or χ2 test from a 2 × 2 contingency table.

Table 3.

Haplotype frequencies between UC patients and healthy controls in IFITM1 SNPs.

| Haplotype |

Frequencya |

Chi-square | Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs77537847 | rs11246062 | Control | UC | ||

| A | C | 0.621 | 0.578 | 1.389 | 0.239 |

| G | C | 0.197 | 0.222 | 0.722 | 0.396 |

| G | G | 0.177 | 0.200 | 0.644 | 0.422 |

| Others | 0.005 | 0.000 | – | – | |

Values were constructed by EM algorithm with genotyped SNPs.

Values were analyzed by Chi-square.

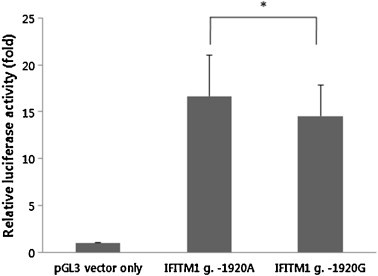

To evaluate the putative functional polymorphisms, we assessed actual promoter activity with the luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 3 ). We prepared two reporter constructs that contained the A or G allele of the human IFITM1 gene g.-1920G>A polymorphisms. In the SW480 cells, the luciferase activity in the cells with the A allele in the IFITM1 g.-1920G>A polymorphism was significantly higher than that in the cells with the G allele (P = 0.05). This result suggests that the g.-1920A allele might affect the increased transcriptional activity of the IFITM1 gene in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Relative luciferase activities between the A allele and the G allele of the IFITM1 g.-1920G>A. IFITM1 g.-1920A and IFITM1 g.-1920G represent luciferase activities in two constructs with a major allele (g.-1920A) and a minor allele (g.-1920G), respectively. Control represents luciferase activity without polymorphism as a standard (pGL3). Data were obtained from multiple independent experiments and are represented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.05.

4. Discussion

IBD is a chronic disease that is frequently encountered in the gastrointestinal tract and it can profoundly affect the quality of life. Although great advances have been made in the management of IBD with the introduction of immune-modulators and monoclonal antibodies, the precise etiology of IBD is unclear. However, IBD is thought to be the result of an aberrant intestinal immune response to bacterial microflora and this occurs in genetically susceptible individuals. Multiple IBD susceptibility loci (referred to as IBD 1–9) have been implicated in genomic studies in human. The most extensively studied genetic region, associated with IBD, among these loci is the IBD1 locus (16p13.1–16q12.2). The NOD2 gene, which has been widely shown to influence both the susceptibility and phenotype of patients with CD, is located at the IBD1 locus [19], [20], [21]. Most studies have shown an association between NOD2 mutations and the susceptibility to CD, but not to UC. We previously reported that an exon 4 variation of the Tim-1 gene and the SNPs of the IL27, TNFRSF17 and EED genes were associated with UC in a Korean population [18], [22], [23], [24].

The human IFITM1 gene, a member of the IFITM family, consists of two exons and one intron. IFITM proteins were first discovered in T98G neuroblastoma cells that express the proteins in response to interferon stimulation [25]. We have previously identified 7 SNPs in IFITM3 and have suggested that the IFITM3 polymorphism is associated with a susceptibility to UC [16]. The IFITM1 gene was selected as a candidate gene for UC by our cDNA microarray analysis (our unpublished data) because the expression level of the IFITM1 gene was more increased in the UC mouse model than that of the healthy control mouse. These results were led us to determine whether or not the IFITM1 SNPs are associated with susceptibility to UC in this study.

We showed that the expression level of IFITM1 mRNA was stable in the human digestive system (Fig. 1), and identified a total of four polymorphisms (two SNPs and two variations) in the IFITM1 gene (Fig. 2). The genotype frequency of g.-1920G>A polymorphisms in UC patients was significantly different from that of the healthy control group (Table 2). This result strongly suggests that SNPs of IFITM1 may be associated with susceptibility to UC. These results led us to think it is interesting to know that IFITM1 gene polymorphism (g.-1920G>A) may have some influence on the susceptibility to UC. This may happen because the polymorphisms within the binding site of the promoter region may influence the expression level by suppression or activation of binding between the specific transcriptional binding site and transcription factor. Due to its implication, we decided to investigate the role of the g.-1920G>A polymorphism in the IFITM1 by luciferase reporter assay. Our result shows that the luciferase activity for the A allele with g.-1920G>A polymorphism was higher than that for the G allele in the SW480 cells (Fig. 3). This result indicates that the g.-1920G allele might affect the decreased transcriptional activity level of the IFITM1 gene in vivo, and it might have an influence on the susceptibility to UC.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not check the expression levels of IFITM1 in UC patients and did not show the clinical impact of IFITM1 SNPs on UC. It will be also interesting to show the expression levels of the IFITM1 in the colon tissues of UC patients by further studies. Our results suggest a possibility that IFITM1 SNPs may be involved in inflammation by an unknown pathway in UC pathogenesis.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that the IFITM1 gene might be a candidate gene associated with the pathogenesis of UC. Although it is not clear how the IFITM1 polymorphisms are related to the susceptibility of UC, our results provide useful information for further functional studies of the IFITM1 gene or IFITM gene family, and gastrointestinal disease such as colorectal cancer and inflammatory responses.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2010-0002842).

References

- 1.Blumberg R.S., Saubermann L.J., Strober W. Animal models of mucosal inflammation and their relation to human inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:648–656. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podolsky D.K. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuss I.J., Neurath M., Boirivant M., Klein J.S., de la Motte C., Strong S.A. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plevy S.E., Landers C.J., Prehn J., Carramanzana N.M., Deem R.L., Shealy D. A role for TNF-alpha and mucosal T helper-1 cytokines in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. J Immunol. 1997;159:6276–6282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targan S.R., Deem R.L., Liu M., Wang S., Nel A. Definition of a lamina propria T cell responsive state. Enhanced cytokine responsiveness of T cells stimulated through the CD2 pathway. J Immunol. 1995;154:664–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y., Lee J.H., Kim K.Y., Song H.K., Kim J.K., Yoon S.R. The interferon-inducible 9-27 gene modulates the susceptibility to natural killer cells and the invasiveness of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2005;221:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreu P., Colnot S., Godard C., Laurent Puig P., Lamarque D., Kahn A. Identification of the IFITM family as a new molecular marker in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1949–1955. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J., Pan Q., Rong L., He W., Liu S.L., Liang C. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol. 2011;85:2126–2137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang I.C., Bailey C.C., Weyer J.L., Radoshitzky S.R., Becker M.M., Chiang J.J. Distinct patterns of IFITM-mediated restriction of filoviruses, SARS coronavirus, and influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(1):e1001258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brass A.L., Huang I.C., Benita Y., John S.P., Krishnan M.N., Feeley E.M. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewin A.R., Reid L.E., McMahon M., Stark G.R., Kerr I.M. Molecular analysis of a human interferon-inducible gene family. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange U.C., Saitou M., Western P.S., Barton S.C., Surani M.A. The fragilis interferon-inducible gene family of transmembrane proteins is associated with germ cell specification in mice. BMC Dev Biol. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S.S., Yamaguchi Y.L., Tsoi B., Lickert H., Tam P.P. IFITM/Mil/fragilis family proteins IFITM1 and IFITM3 play distinct roles in mouse primordial germ cell homing and repulsion. Dev Cell. 2005;9:745–756. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang G., Xu Y., Chen X., Hu G. IFITM1 plays an essential role in the antiproliferative action of interferon-gamma. Oncogene. 2007;26(4):594–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo G.S., Lee J.K., Yu J.I., Yun K.J., Chae S.C., Choi S.C. Identification of the polymorphisms in IFITM3 gene and their association in a Korean population with ulcerative colitis. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42:99–104. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.2.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chae S.C., Song J.H., Pounsambath P., Yuan H.Y., Lee J.H., Kim J.J. Molecular variations in Th1-specific cell surface gene Tim-3. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:274–278. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae S.C., Yu J.I., Oh G.J., Choi C.S., Choi S.C., Yang Y.S. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TNFRSF17 gene and their association with gastrointestinal disorders. Mol Cells. 2010;29:21–28. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampe J., Cuthbert A., Croucher P.J., Mirza M.M., Mascheretti S., Fisher S. Association between insertion mutation in NOD2 gene and Crohn's disease in German and British populations. Lancet. 2001;357:1925–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugot J.P., Chamaillard M., Zouali H., Lesage S., Cézard J.P., Belaiche J. Association of NOD2 leucinerich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogura Y., Bonen D.K., Inohara N., Nicolae D.L., Chen F.F., Ramos R. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C.S., Zhang Q., Lee K.J., Cho S.W., Lee K.M., Chae S.C. Interleukin 27 polymorphisms are associated with inflammatory bowel diseases in a Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1692–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park Y.R., Choi S.C., Lee S.T., Kim K.S., Chae S.C., Chung H.T. The association of eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3 gene polymorphisms in a Korean population with ulcerative colitis. Exp Mol Med. 2005;37:553–558. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J.I., Kang I.H., Seo G.S., Choi S.C., Yun K.J., Chae S.C. Promoter polymorphism of the EED gene is associated with the susceptibility to ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(6):1537–1543. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman R.L., Manly S.P., McMahon M., Kerr I.M., Stark G.R. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of interferon-induced gene expression in human cells. Cell. 1984;38:745–755. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]