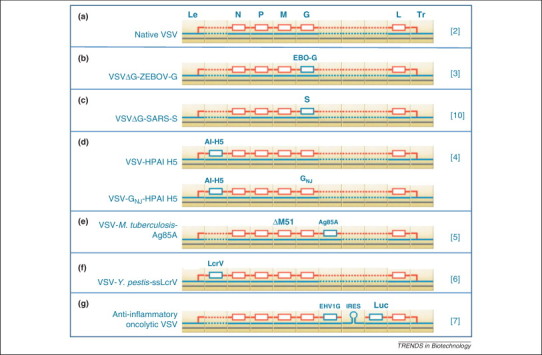

Recent advances in synthetic biology have opened up the possibility of finely engineering viral genomes with the goal to understand and prevent viral diseases [1]. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is one of the most promising viruses for engineering vaccines and oncolytic therapies [2]. Its genome is able to accept large foreign sequences (Figure 1 ). VSV also remains viable as a pseudotyped virus (an enveloped virus expressing foreign glycoproteins in place of the native surface proteins) [3]. The broad tissue tropism allows for many different routes of administration, such as nasal sprays or intramuscular injection. VSV can be reliably grown to high titers in cell types approved for vaccine production. Finally, negligible pre-existing immunity to this vector exists in the general population.

Figure 1.

Logical representation of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) genome structure. The natural VSV genome (a) is composed of five open reading frames bounded by a 3′ leader sequence (Le) and a 5′ trailer region (Tr). Sequences coding for foreign antigens can be inserted in 3′ of the nucleoprotein (N) gene and between the glycoprotein (G) and large polymerase protein (L) genes. These locations are indicated by broken lines in (a). The Ebola vaccine was designed by replacing the VSV G protein with the Ebola G protein, leading to a replicating pseudotyped vector (b). Similarly, a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) vaccine was designed by replacing the VSV G protein with the SARS spike (S) protein (c). The avian influenza vaccine relies on the insertion of a sequence coding for the H5 antigen immediately next to the leader sequence (d). Interestingly, the booster vaccine carries a different variant of the VSV G protein to escape the anti-VSV immune response acquired during the primary immunization. The tuberculosis vaccine relies on the insertion of an antigen between G and L (e). The Yersinia pestis vaccine is structurally comparable to the avian influenza vaccine (f). Finally, the anti-inflammatory oncolytic VSV has a large insert between G and L. The insert includes an anti-inflammatory glycoprotein (EHV1G) and a reporter gene (Luc) separated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (g). These logical maps were generated using GenoCAD [11].

Protection against viral infections

VSV-vectored vaccines have been explored as a strategy to protect against many emerging viral infections, exhibiting exceptional safety and efficacy. Of particular interest is a study in which VSV expressing the H5 antigen from highly pathogenic avian influenza induced sterilizing immunity against heterologous challenge in mice [4]. In this experiment, it was impossible to detect challenge virus in lungs 3 days post-challenge. One study vaccinated and challenged macaques immunocompromised by simian–human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infection [3]. The vaccine was well tolerated, and protected 67% of the vaccinated subjects from lethal Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV) challenge. All unvaccinated animals succumbed by day 10 post-challenge. Only the most severely immunocompromised vaccinated subjects succumbed to ZEBOV challenge. This demonstrates the safety and efficacy potential of VSV when live virus vaccination would otherwise be contraindicated.

Protection against bacterial infections

Although viral vectors are not traditionally utilized for vaccination against bacterial agents, they do have the potential for protection against intracellular bacteria. A significant level of protection has been reported against challenge with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice 2 weeks post-vaccination [5]. This protection coincided with elevated but short-lived CD8+ T cells and interferon (IFN)-γ-producing T cells following intramuscular injection. Even more promising, recombinant VSV expressing a secreted form of a virulence factor protein for Yersinia pestis, LcrV, induced high levels of LcrV-specific antibodies, protecting 90% of the mice challenged with 10 LD50 [6].

Protection against cancerous cells

VSV is known to be exquisitely sensitive to IFN. Many cancerous cells, unlike normal cells, are deficient in their IFN responses. Therefore, it is possible for VSV to kill tumor cells, leaving healthy tissue at tumor margins unharmed. VSV is highly immunogenic, therefore, it can be detected and neutralized by the immune system before tumors are sufficiently destroyed. Introducing the anti-inflammatory glycoprotein from equine herpesvirus 1 into the VSV genome helped the virus to replicate more effectively in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma [7]. This resulted in a significant increase of the area of necrotic cells within the tumor. It also increased the survival of the animals.

Safety first

The safety of VSV has been demonstrated in immunocompromised macaques [3]. The neurovirulence observed in some VSV infections has been a source of concern. However, researchers have identified mutations erasing neurological signs 8, 9. Surprisingly, it has also been demonstrated that a replication-deficient vector may be a more potent vaccine than a replication-competent one [10]. This observation addresses many safety issues related to the use of replicating viruses.

A more significant milestone is the start of the first clinical trials of vaccines derived from VSV. Two clinical trials are recruiting healthy, HIV-free volunteers to examine the safety of potential HIV vaccines. These Phase I studies will use either VSV expressing the HIV Gag protein as a primary vaccine (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01438606), or VSV-HIV Gag as a booster to primary vaccination with DNA expressing HIV Gag and interleukin-12 as an adjuvant (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01578889). Successes of these trials will dramatically increase the viability of VSV derivatives in clinical applications.

Future of VSV as a synthetic biology chassis

In light of promising successes in a wide variety of laboratory studies, it seems as though VSV will become a chassis of choice for engineering therapeutic viruses targeting a broad range of diseases. The genome is small enough to be manipulated in bacterial plasmids. Its structure is simple enough to be modeled using Computer Assisted Design software applications for synthetic biology. For instance, GenoCAD [11] was used to generate the logical representations of the therapeutic viruses reviewed in this letter (Figure 1). The coalescence of progress in synthetic biology and VSV biology are likely to result in the development of a new generation of prophylactic and therapeutic viruses against a broad range of infectious and oncologic diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Science Foundation Award EF-0850100 and a seed grant from the Virginia Tech Institute for Critical Technologies and Applied Science.

References

- 1.Wimmer E. Synthetic viruses: a new opportunity to understand and prevent viral disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:1163–1172. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichty B.D. Vesicular stomatitis virus: re-inventing the bullet. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geisbert T.W. Vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola vaccine is well-tolerated and protects immunocompromised nonhuman primates. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000225. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz J.A. Potent vesicular stomatitis virus-based avian influenza vaccines provide long-term sterilizing immunity against heterologous challenge. J. Virol. 2010;84:4611–4618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02637-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roediger E.K. Heterologous boosting of recombinant adenoviral prime immunization with a novel vesicular stomatitis virus-vectored tuberculosis vaccine. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay A. Single-dose, virus-vectored vaccine protection against Yersinia pestis challenge: CD4(+) cells are required at the time of challenge for optimal protection. Vaccine. 2008;26:6329–6337. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altomonte J. Exponential enhancement of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus potency by vector-mediated suppression of inflammatory responses in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:146–153. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J.E. Neurovirulence properties of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors in non-human primates. Virology. 2007;360:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozduman K. Peripheral immunization blocks lethal actions of vesicular stomatitis virus within the brain. J. Virol. 2009;83:11540–11549. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02558-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapadia S.U. SARS vaccine based on a replication-defective recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus is more potent than one based on a replication-competent vector. Virology. 2008;376:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czar M.J. Writing DNA with GenoCAD (TM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W40–W47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]