Summary

To achieve the greatest output from their limited genomes, viruses frequently make use of alternative open reading frames, in which translation is initiated from a start codon within an existing gene and, being out of frame, gives rise to a distinct protein product. These alternative protein products are, as yet, poorly characterized structurally. Here we report the crystal structure of ORF-9b, an alternative open reading frame within the nucleocapsid (N) gene from the SARS coronavirus. The protein has a novel fold, a dimeric tent-like β structure with an amphipathic surface, and a central hydrophobic cavity that binds lipid molecules. This cavity is likely to be involved in membrane attachment and, in mammalian cells, ORF-9b associates with intracellular vesicles, consistent with a role in the assembly of the virion. Analysis of ORF-9b and other overlapping genes suggests that they provide snapshots of the early evolution of novel protein folds.

Introduction

To achieve expression of viral proteins during infection, viruses exploit many aspects of the host biology, such as transcription (McKnight and Tjian, 1986), RNA export (Harris and Hope, 2000), capping and methylation (Cougot et al., 2004), as well as translation (Sonenberg and Dever, 2003). Viruses also use specific strategies, such as RNA editing (Turelli and Trono, 2005) and splicing (Pongoski et al., 2002), to enrich the diversity of viral proteins produced from the usually rather small viral genome. A particularly bizarre phenomenon, especially in RNA viruses, is the use of multiple start codons within a gene which gives rise to different protein products (Samuel, 1989). The presence of these so-called alternative open reading frames (ORFs) and their translation has been shown to occur by several mechanisms (reviewed in Jackson, 1996): leaky scanning, where the usual start codon of a gene is in an unfavorable sequence context, so that a fraction of ribosomal scanning complexes fail to initiate and continue scanning to the next start codon; internal ribosome entry sites; ribosomal shunting (where, during scanning, ribosomal complexes translocate to a remote position on the mRNA and initiate translation there); and translational reinitiation after termination.

Alternative ORFs and their mechanisms of translational initiation have been described in many viral systems, including influenza B (Shaw et al., 1983), Sendai virus (Giorgi et al., 1983), and reovirus (Ernst and Shatkin, 1985, Jacobs and Samuel, 1985), as well as group 2 coronaviruses, such as mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and bovine coronavirus (BCV) (Fischer et al., 1997, Senanayake and Brian, 1997). So far, most of the research on alternative ORFs has focused on the mechanisms for initiation of translation, while the molecular structures and functions of the corresponding proteins have received little attention. This is somewhat surprising, given that the special nature of such proteins (each arising from a “gene inside another gene”) is likely to give new insights into protein structure and evolution.

Recently, a coronavirus was identified as the causative agent of an emerging disease, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Ksiazek et al., 2003). During its first outbreak in 2003, SARS led to at least 8000 infections and over 750 fatalities (Donnelly et al., 2003). The SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) genome consists of approximately 29,700 nucleotides encoding a predicted 28 proteins (Marra et al., 2003, Rota et al., 2003), including several alternative ORFs. These occur in the 3′ region of the genome, which encodes structural and accessory proteins that are involved in the assembly of the virus particle (see Figure 1). Although the precise details of coronavirus assembly are not well understood, the consensus model is that the RNA genome is packaged in the cell cytoplasm by multiple copies of the relatively well conserved (Stadler et al., 2003) N-protein to form the nucleocapsid. The nucleocapsid then associates with the viral membrane proteins M, S, and E in the ER-to-Golgi intermediate compartment, where virus particles assemble and bud into the Golgi. In SARS-CoV, as in other group 2 coronaviruses, an additional protein is synthesized (called ORF-9b in SARS-CoV and internal or I-protein otherwise) from an alternative reading frame of the N-gene. In BCV, the I-protein is produced in an exact molar ratio with the N-protein (Senanayake and Brian, 1997) and in MHV it is present in the assembled virion, suggesting that it acts as an accessory structural protein in viral assembly (Fischer et al., 1997). The MHV I-protein is not essential for the production of viable virus; however, it does confer a selective advantage for virus growth (Fischer et al., 1997). Although little is known about the equivalent protein in SARS Co-V, antibodies against ORF-9b have been found in patients, demonstrating that it is produced during infection (Qiu et al., 2005).

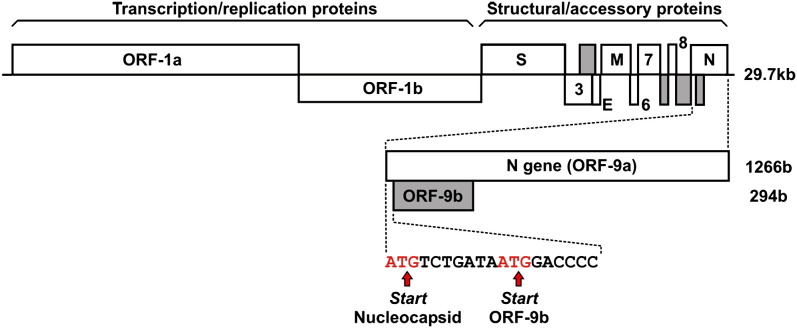

Figure 1.

The Structure of the SARS-CoV Genome

Alternative open reading frames (ORF-3b, -7b, -8b, and -9b) are highlighted in gray. The nucleocapsid (N) gene including its internal alternative open reading frame, ORF-9b, is shown in an enlarged representation. S, spike protein; 3, ORF-3; E, envelope protein; M, membrane protein; 6, ORF-6; 7, ORF-7; 8, ORF-8; N, nucleocapsid protein (adapted from Snijder et al., 2003; genome representation is not to scale).

We are pursuing an investigation into the structures of proteins from SARS-CoV (Sutton et al., 2004). Here we report the crystal structure of ORF-9b, which we demonstrate functions as an unusual lipid binding protein and possesses a novel fold. In addition, we show that ORF-9b expressed in mammalian cells colocalizes with cellular vesicles, indicating a role in virus assembly via membrane association. To our knowledge, the structure represents the first example of a viral protein translated as an alternative open reading frame elucidated at high resolution, and we suggest that its unusual features may reflect its recent evolutionary origin.

Results and Discussion

Structure Determination

The structure of ORF-9b was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) analysis of a selenomethionated form of the protein expressed in Escherichia coli (see Experimental Procedures and Table 1 for details). The crystals diffracted X-rays weakly (overall B factor 84 Å2), limiting the analysis to Bragg spacings of 2.8 Å (R = 26.6%, Rfree = 28.9%), and a significant portion of the structure is not well ordered. Nevertheless, due to the presence of 8-fold noncrystallographic symmetry, we can be confident that the interpretation of the structure is reliable.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data Recording, Model Building, and Refinement Statistics

| Data Collection | |

|---|---|

| Experiment | Single-wavelength anomalous dispersion |

| X-ray source | ESRF BM14 |

| Wavelength | 0.97903 |

| Resolution (Å) | 19.9–2.8 (2.9–2.8) |

| Unique reflections | 22,040 |

| Redundancy | 14.9 (15.1) |

| Completeness | 99.8 (100) |

| Rmergea (%) | 11.1 (b) |

| I/σ(I) | 22.8 (1.3) |

| Space group | P42 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 140.1, c = 45.2 |

| No. of molecules (AU) | 8 |

| Solvent content (%) | 52 |

| Refinement | |

| R value (%) | 26.6 (40.4) |

| Free R value, random 5% (%) | 28.9 (43.2) |

| Rmsd bond length (Å) | 0.009 |

| Rmsd bond angle (°) | 1.8 |

| Rmsd B, bonded atoms (Å2) | 7 |

| Rmsd Cα, corec (Å) | 0.25 |

| Rmsd Cα, overallc (Å) | 4.6 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Allowed regions | 97.3% |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.5% |

| Disallowed regions | 1.3% |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shells.

Rmerge = ΣhΣi |Ii (h) − <I(h)>| / ΣhΣi<Ii (h) >, where Ii (h) is the ith measurement and <I(h)> is the weighted mean of all measurements of Ii (h).

The R factor for the highest resolution shell exceeds 100%, as expected from the extreme weakness of the data (B factor from the Wilson plot, 84 Å2); however, the very high redundancy (15) allows some useful data to be obtained in this shell.

Core regions exclude the flexible ∼4 N-terminal residues and flexible loops: 24–41 (residues 26–37 are not modeled), 48–52, 64–71, 89–91.

The Protein Fold

The crystal structure reveals ORF-9b to be a 2-fold symmetric dimer constructed from two adjacent twisted β sheets ( Figure 2A). Each of these sheets is formed from β strands contributed by both monomers which form a highly interlocked architecture reminiscent of a handshake (Figure 2B). These extensive interactions bury over 1500 Å2 of surface area of each subunit on formation of the dimer (calculated with NACCESS; Hubbard et al., 1991), typical of the contact area of protein dimers (Lesk, 2004), strongly suggesting a biologically relevant interaction. The hydrodynamic properties of the protein in solution (determined by dynamic light scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation; see the Supplemental Data available with this article online) are consistent with it being a dimer.

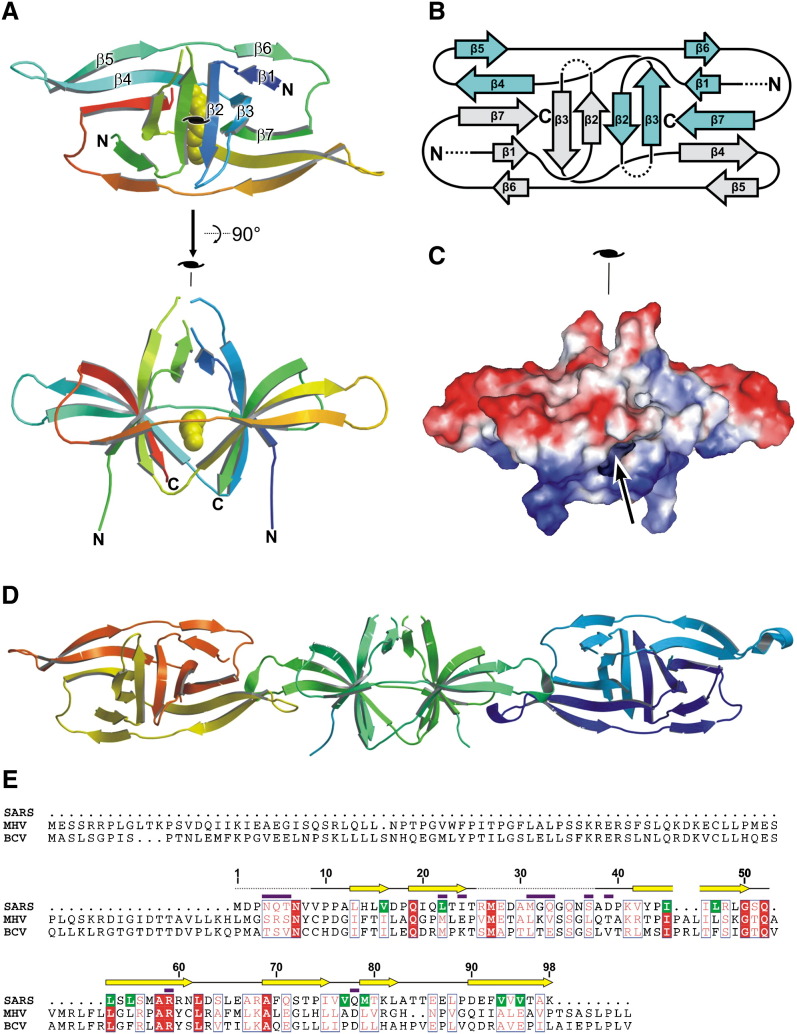

Figure 2.

The Crystal Structure of the SARS-CoV ORF-9b Protein

(A) Cartoon representation. Two orthogonal views are presented. In the electron density map, residues 9–25 and 38–98 are resolved. The secondary structural elements are labeled for one subunit in the upper image, β1 13–16, β2 19–24, β3 42–50, β4 53–61, β5 69–75, β6 79–82, and β7 90–98. The lipid ligand is shown as yellow van der Waals radii spheres. The 2-fold symmetry axis is indicated.

(B) Topology diagram illustrating the interlocked architecture of the dimeric structure. Monomers are colored gray and cyan. Disordered regions are represented as dashed lines.

(C) Surface electrostatic representation. In this view, the top of the structure is predominantly negatively charged (red), and the bottom is mainly positively charged (blue). The arrow indicates the opening of the hydrophobic tunnel.

(D) Crystal contacts between ORF-9b molecules. Neighboring dimers are rotated ∼90° around their longest axis, and pack end to end via their β4β5 and β6β7 loops. This gives rise to an assembly reminiscent of a twisted rope.

(E) Sequence alignment of SARS coronavirus ORF-9b and its homologs in mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and bovine coronavirus (BCV). The alignment was performed using MultAlin (Corpet, 1988) and due to the very low level of sequence similarity should be regarded as provisional, pending a proper structure-based analysis. Residue numbering refers to the ORF-9b protein from SARS-CoV. Protein secondary structure is represented as yellow arrows (β strands), solid lines (random coil conformation), and dotted lines (disordered regions). Residues which line the hydrophobic tunnel of ORF-9b are highlighted in green. Magenta bars indicate residues which vary between different SARS isolates (see Supplemental Data for a detailed alignment). The figure was produced with ESPript (Gouet et al., 1999).

The interdigitated nature of the ORF-9b dimer rests on a highly unusual topology of largely antiparallel β sheets in which monomers wrap around each other (Figure 2B). A search of the protein database with both the monomer and dimer using Dali (Holm and Sander, 1993) and SSM (Krissinel and Henrick, 2004) gave no significant structural hits. This suggests that the structure represents a novel fold.

Analysis of the surface electrostatics of ORF-9b shows a highly polarized distribution, in which one side of the molecule is predominantly negatively charged while the other is positively charged (Figure 2C). It is interesting to note that in the electron density map, two regions near the N terminus (residues 1–8 and 26–37) are not resolved. Both of these disordered segments are located on the periphery of the structure, whereas the inner core of the protein is reasonably well ordered.

The crystal of the protein is built up from twisted chains of ORF-9b dimers that form an open three-dimensional mesh, via end-to-end packing of dimers via the β4β5 and β6β7 loops (Figure 2D), to occlude some 700 Å2 of surface area from each dimer.

A Hydrophobic Tunnel

The β sheets of ORF-9b form a tent-like structure which contains a 22 Å long central cavity, lined by hydrophobic side chains, which spans the molecule and is open at both ends (Figures 2E, 3A, and 3B). Within this tunnel, the experimentally phased map shows a finger of electron density (Figure 3A) straddling the molecular dyad, separate from the protein portion of the map. Given the hydrophobic nature of the cavity, we interpreted this feature as an aliphatic molecule bound within the ORF-9b dimer. For the purpose of crystallographic model building and refinement, we have represented this ligand as a hydrocarbon molecule (the resolved electron density is consistent with an unbranched chain of ten carbon atoms; see Figures 3A and 3B).

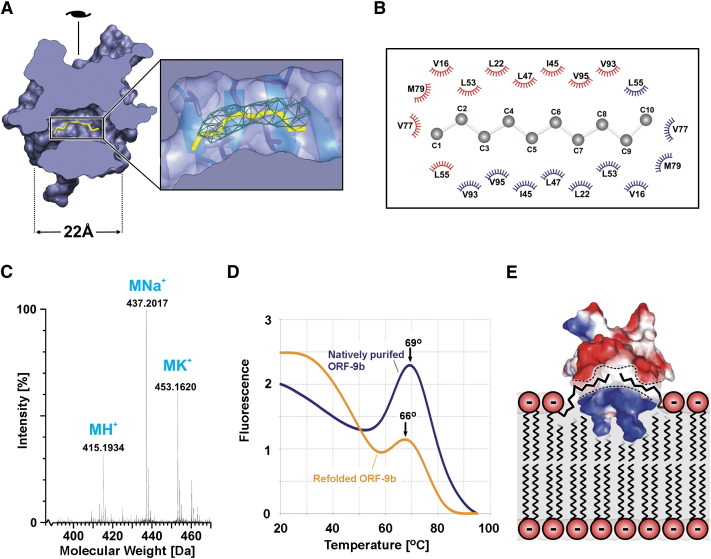

Figure 3.

Lipid Binding of ORF-9b

(A) The protein structure is cut in the center and viewed along its longest axis to reveal the central hydrophobic tunnel. The crystallographically resolved portion of the ligand is shown in yellow; the experimentally phased electron density (contoured at 1σ) is shown in green. The 2-fold symmetry axis lies in the plane of the paper, as indicated.

(B) Cartoon of the residues lining the lipid binding pocket. The lipid is shown in ball-and-stick representation and the residues contributed by the two subunits are distinguished by the color of their contact symbols.

(C) Mass spectrum of the extracted ligand molecule (designated M). Its molecular weight is 414 Da. In the mass spectrum, three significant peaks are observed, suggestive of proton (+1 Da), sodium (+23 Da), and potassium (+39 Da) adducts of a fatty acid molecule. The observed mass is consistent with a saturated long-chain hydroxy fatty acid C25H50O4 (mass 413 Da), such as dihydroxy-pentacosanoate, or a nonhydroxy fatty acid ester C25H50O4 (mass 413 Da) (Christie, 1982).

(D) ThermoFluor assay result for natively purified (lipid-containing) and refolded (lipid-free) ORF-9b. In both cases, there is a strong fluorescence peak at 65°C–70°C, which presumably represents the collapse of the dimeric ORF-9b structure. Refolded ORF-9b peaks at 66°C, whereas natively purified ORF-9b has a peak at 69°C, demonstrating that lipid-containing ORF-9b is slightly more stable than ORF-9b without lipid, suggesting that the lipid has a thermodynamically stabilizing effect on the protein.

(E) Proposed mode of ORF-9b membrane interaction (protein structure represented as in Figure 2B, but rotated by 90° around the vertical 2-fold symmetry axis). The positively charged side of the protein (shown in blue) could interact with the negatively charged lipid head groups, while the hydrophobic pocket (indicated by dashed lines) binds one or more lipid tails.

In order to identify the molecule bound in the tunnel, we carried out a mass spectrometry analysis (shown in Figure 3C) which revealed a single molecular species of molecular weight 414 Da, significantly larger than expected from the visible electron density. The mass spectrometry data suggest that the ligand is a fatty acid (or fatty acid ester) containing approximately 25 carbon atoms. This is entirely consistent with the open architecture of the hydrophobic pocket of ORF-9b, which would allow such large hydrophobic molecules to be accommodated, with atoms hanging from the end(s) of the tunnel (invisible in our crystallographic analysis due to flexibility). The mass analysis is incompatible with the ligand being derived from the detergent present during cell lysis. This suggests that the ligand was picked up from the bacterial expression host and is tightly bound so that it remains associated with the ORF-9b protein during purification. In order to establish whether this was an artifact of the expression system used, refolding experiments (see Experimental Procedures) were performed, which demonstrated that—in the absence of lipid—the protein folds into molecules with hydrodynamic properties identical to those of the lipid-bound structure. Furthermore, thermostability assays (see Figure 3D) show that refolded, lipid-free ORF-9b is slightly less stable than that purified from E. coli, consistent with lipid binding representing a thermodynamic phenomenon.

Given the width of the tunnel, it is likely that ORF-9b can accommodate bulkier or irregularly shaped molecules (for instance, unsaturated lipid chains). In fact, in the crystal structure presented here, the bound ligand occupies under half of the volume of the pore. This is considerably less than for other lipid binding proteins, which have more tight-fitting hydrophobic pockets (see Table 2).

Table 2.

A Comparison of the Hydrophobic Pockets of Different Types of Lipid Binding Proteins

| Protein Structure | PDB Code (Literature Reference) | Type of Ligand | Volume of the Pore (Å3) | Volume of the Ligand in the Pore (Å3) | Percentage of Pore Occupied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV ORF-9b | 2CME | Long-chain fatty acid | 365 | 166 | 45% |

| Human CD1b | 1GZP (Gadola et al., 2002) | Ganglioside GM2 (glycolipid) | 1564 | 881 | 56% |

| Poliovirus | 2PLV (Filman et al., 1989) | Sphingosine (long-chain amino alcohol) | 292 | 176 | 60% |

An Unusual Type of Membrane Binding Protein

Expression in mammalian cells (see Experimental Procedures) reveals that ORF-9b is membrane bound and appears to be associated with intracellular vesicular structures ( Figures 4A and 4B). Given that expression of the protein in E. coli gives soluble protein, this suggests that ORF-9b specifically recognizes and binds to intracellular membranes in eukaryotes.

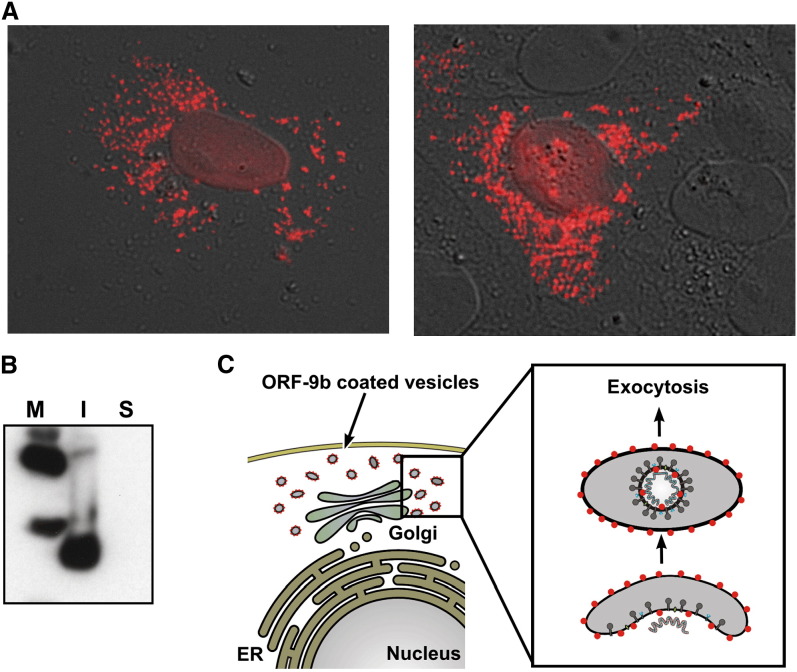

Figure 4.

Expression and Intracellular Location of ORF-9b in 293T Mammalian Cells

(A) Differential interference contrast microscopy (gray) overlapped with epifluorescence using an anti-His fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody (red). The protein is associated with intracellular vesicular structures.

(B) Partitioning experiment, in which the 293T cells expressing ORF-9b were fractionated into soluble (cytosolic) and insoluble/noncytosolic (nuclear, intravesicular, membrane-associated) phases. Western blotting with a specific antibody shows that ORF-9b is in the insoluble fraction, most likely membrane attached as suggested by (A). M, molecular weight markers; I, insoluble phase; S, soluble phase.

(C) Cartoon representation of the intracellular localization of ORF-9b (red dots) and its possible function in the assembly of the SARS coronavirus. In this model, ORF-9b is located on the cytosolic side of intracellular vesicles, serving as an attachment point for components of the nascent virus and/or as a modulator of membranes. Currently it is unknown whether ORF-9b is present in the assembled virus particle; however, the homologous protein is known to be present in particles of MHV (Fischer et al., 1997).

Considering the polarized surface and hydrophobic tunnel of the protein, it is most likely that the ORF-9b molecule immerses itself in the lipid head groups of the membrane and becomes anchored by internalizing one or more lipidic tails (illustrated in Figure 3E). This would be the opposite of the more usual covalent attachment of lipid tails to proteins, and would represent an unusual mode of membrane interaction. Indeed, we are aware of only one similar example in the literature—that of the conserved eukaryotic protein bet3, which appears to interact with the Golgi by binding myristate chains of the phospholipid bilayer in a well-defined pocket (Kim et al., 2005).

Function of the Protein in the Life Cycle of the SARS Virus

At present, there is little published work on ORF-9b, so the precise function of the protein remains uncertain. Most of our current knowledge comes from homologous gene products in other coronaviruses, most importantly the work on MHV and BCV discussed above, where the protein has been shown to be present as a structural component in the virus particle (Fischer et al., 1997) and is likely to be an accessory protein in virus assembly. Because the protein occurs as an alternative open reading frame of the viral nucleocapsid gene, it has been suggested to serve as an interaction partner of the corresponding N-protein (Senanayake and Brian, 1997).

Combining these observations with our structural and functional studies, it seems plausible that ORF-9b has a role in membrane interactions during the assembly of the virus (although other possible functions cannot be ruled out). It could act as an attachment point onto the membrane for other proteins, such as the N-protein, which is known to bind to membranes via protein-protein interactions, even though the details are not well understood at present (de Haan and Rottier, 2005). Alternatively, ORF-9b could act as a modulator of membranes themselves, for example by promoting vesicle formation and budding (both of which are key stages in the assembly of coronaviruses). In this regard the higher order assembly of ORF-9b in the crystal, as interconnected twisted ropes (see Figure 2D), may be partially recapitulated at the membrane surface, imparting some torque on the membrane. The possible role of ORF-9b in the assembly of the SARS virus is illustrated in Figure 4C.

The Evolution of ORF-9b and Homologs in Other Coronaviruses

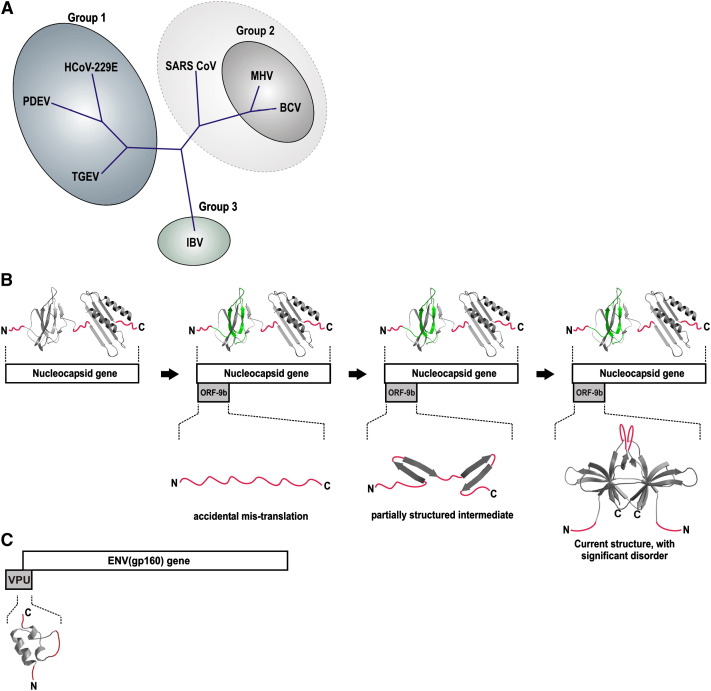

The sequence of ORF-9b is well conserved in different SARS isolates (see Supplemental Data). As discussed above, several other, mainly group 2, coronaviruses (e.g., MHV and BCV) also have an alternative ORF in their nucleocapsid gene. There is good sequence conservation of the alternative ORF in these group 2 coronaviruses, but rather little similarity with SARS-CoV ORF-9b (see Figure 2E). This intermediate relationship reflects the evolution of SARS-CoV, which has been suggested to be an early split-off from the group 2 coronavirus subfamily (see Figure 5A) (Snijder et al., 2003). Functionally, the ORF-9b homolog of MHV acts as an accessory structural protein that is not essential for viral infection but confers a small growth advantage (Fischer et al., 1997), presumably explaining why non-group 2 coronaviruses can function without the protein. Taken together, these observations argue that the internal ORF of the N-gene of group 2 coronaviruses evolved after the N-protein (which, in contrast, is present and reasonably conserved in all coronaviruses; Stadler et al., 2003). The most likely mechanism by which such an alternative ORF could arise would be as an “accidental” mistranslation of the N-gene that subsequently evolved into a structured and functional protein (Figure 5B). This hypothesis is consistent with the crystal structure presented here, as, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that it resembles any other known protein fold.

Figure 5.

The Structural Evolution of Alternative Open Reading Frames in Viruses

(A) The evolution of coronaviruses (adapted from Snijder et al., 2003). Based on their genome sequence, coronaviruses fall into three main groups. SARS-CoV is thought to be an early split-off from the group 2 lineage (indicated by a dashed circle). Alternative open reading frames of the nucleocapsid gene are found only in group 2 viruses, such as MHV and BCV (Senanayake and Brian, 1997), as well as group 2-related viruses, including SARS-CoV. BCV, bovine coronavirus; HCoV-229E, human coronavirus 229E; IBV, infectious bronchitis virus; MHV, murine hepatitis virus; PDEV, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; TGEV, transmissible gastroenteritis virus.

(B) A model for the structural evolution of ORF-9b within the SARS-CoV N-gene. Starting from an N-gene without an alternative ORF, the protein first arises as an “accidental” translation product, which is mostly unstructured. By gradual constrained evolution, it becomes increasingly structured, eventually attaining its present fold. In this scheme, disordered regions (colored in red) are a relict of the evolutionary trajectory of the protein. The N-protein is represented as a composite of two NMR structures of its well-conserved N- and C-terminal domains (Chang et al., 2005a, Huang et al., 2004), which are thought to be surrounded by flexible linkers (Chang et al., 2005b) (colored in red). The region of the N-terminal domain which overlaps with ORF-9b is shown in green.

(C) For comparison, an illustration of the HIV1 vpu and env genes, which partially overlap. The NMR structure of the overlapping portion of VPU (Willbold et al., 1997) (PDB code: 1VPU) is shown. This protein is relatively poorly ordered (rmsd = 1.6 Å between multiple determinations of the fold, for all Cα atoms). The least ordered regions (rmsd > 2 Å) are highlighted in red.

Implications for the Structural Evolution of Alternative Open Reading Frames

Alternative open reading frames are coupled to their corresponding “conventional” reading frame on a genetic level (in the case of ORF-9b, the conventional ORF is the SARS-CoV N-protein). Changes in the DNA sequence will therefore affect both the conventional and alternative ORF, limiting the rate and extent to which the corresponding proteins can evolve. The result will be a “constrained evolution,” an idea which has been demonstrated for regions of viral genes which (partially) overlap (Mizokami et al., 1997). Because ORF-9b is entirely contained within its corresponding conventional gene, the constraint applies to the entire protein. The properties of coupled gene products are likely to be suboptimal compared to proteins that can evolve independently. In the early stages of the evolution of the alternative reading frame, this protein might be expected to be rather poorly folded, whereas eventually there would presumably be a balance, struck by selection, with both protein products being somewhat compromised. Thus, the structural disorder observed in ORF-9b (evinced in the considerable divergence of the eight noncrystallographically related molecules; see Table 1) may reflect its relatively recent invention and the hindrance to its rapid evolution imposed by the coupling to the essential N-gene.

Support for this general hypothesis comes from a system which shares some similarity with the case presented here: in lentiviruses, the vpu and env genes—although not strictly alternative ORFs—share a considerable overlapping region (Figure 5C). Similar to ORF-9b, vpu encodes a small accessory protein which is present only in a subfamily of lentiviruses (namely, human immunodeficiency virus type 1, HIV-1). Although various molecular functions have been described for the protein, its precise role in HIV-1 pathogenesis remains unclear (Hout et al., 2004). In the vpu gene, the region which overlaps with the neighboring env gene encodes its cytoplasmic domain, whose structure has been determined by NMR (Willbold et al., 1997). This small domain shows two well-defined helical regions and, like ORF-9b, a considerable amount of poorly defined structure (Figure 5C).

Conclusions

The structure of ORF-9b, an intertwined dimer with an amphipathic outer surface and a long hydrophobic lipid binding tunnel, suggests how this protein may interact, via an unusual anchoring mechanism, with compartments of the ER-Golgi network to act as an accessory protein during the assembly of the SARS virion. These unusual structural and functional properties are probably a reflection of the distinct evolutionary trajectory of alternative open reading frames. Indeed, we propose that the constraints under which alternative open reading frames evolve give rise to characteristic structural features, most importantly the potential for novel folds and structural disorder. While further studies and structures will be required to test this hypothesis, alternative open reading frames provide powerful model systems to test ideas about protein folding and evolution.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning and Production of Selenomethionine-Labeled Protein for Structural Studies

The coding sequence of SARS-CoV ORF-9b was amplified by PCR (forward primer: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCGAAGGAGATAGAACCATGCATCACCATCACCATCACATGGACCCCAATCAAACCAACG-3′; reverse primer 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTCATTTTGCCGTCACCACCACG-3′). The forward primer encodes a start codon and hexahistidine tag N-terminal to the gene and both forward and reverse primers contain the attB site of the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen). The PCR fragments were subcloned into the pDEST14 plasmid (Invitrogen). For expression of the selenomethionine-labeled protein, the pDEST14 plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain Rosetta pLysS (Novagen). Cultures were grown in selenomethionine media (Molecular Dimensions) spiked with 1% glucose as well as lysine, threonine, and phenylalanine (100 μg/ml each) and leucine, isoleucine, valine, and selenomethionine (50 μg/ml each). Cells were grown at 310 K until an OD595 nm of 0.6 was reached, and then cooled to 293 K for 30 min. Expression was induced by the addition of isopropylthiogalactoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and the cultures were grown for a further 20 hr at 293 K. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 1% Tween-20, 10 mM imidazole. The cells were lysed using a cell disruptor (Constant Systems) and the sample was clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min. To the supernatant, 2 ml of Ni-NTA superflow (Qiagen) was added and the sample was stirred for 2 hr at 4°C. The Ni-NTA beads were subsequently washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and protein was eluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole. The eluted material was further purified by gel filtration in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences). Full selenomethionine incorporation of the purified protein was confirmed by mass spectrometry (data not shown).

Crystallization and Data Collection

Crystallization was carried out using a Cartesian robotic dispensing system (Genomic Solutions) (Walter et al., 2005) and crystal growth was monitored using the OPPF storage and imaging system (Mayo et al., 2005). Diffraction quality crystals grew within 1–2 days in 300 nl sitting drops containing 6.3 mg/ml purified ORF-9b protein, 11% PEG-3350, 66 mM MgCl2, 33 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 20 mM NAD equilibrated against a reservoir solution of 32% PEG3350, 200 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2).

Crystals were cryoprotected in perfluoropolyether oil PFO-X125/03 (Lancaster) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen (100 K). Single-wavelength anomalous diffraction data were collected at the ESRF beamline BM14 (Grenoble, France) and processed using the programs DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The data were weak, especially at higher resolution, as reflected in the poor R factors (Table 1); however, the high redundancy means that the merged data were reasonably reliable.

Model Building and Refinement

The selenium substructure was solved using the programs HKL2MAP and SHELXD (McRee, 1999, Pape and Schneider, 2004, Schneider and Sheldrick, 2002, Sheldrick, 2002). Phase refinement was carried out using SHARP (de La Fortelle and Bricogne, 1997), maps were calculated using CCP4 programs (CCP4, 1994), solvent-flattened using Pirate (Cowtan, 2000), and averaged using GAP (J.M.G. and D.I.S., unpublished program). The presence of partially disordered regions, together with the complex topology of the protein, made the interpretation of the crystallographic data challenging. Model building and refinement used the programs Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and CNS (Brünger et al., 1998). Initial refinement imposed strict 8-fold noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) constraints. In further rounds of refinement, 8-fold NCS restraints were used. Data processing, refinement, and model building statistics are shown in Table 1.

Calculation of the Hydrophobic Pore Dimensions and Ligand Occupancy

The dimensions of the pockets of the structures of ORF-9b, poliovirus (Filman et al., 1989), and human CD1b (Gadola et al., 2002) were determined as the volume accessible to solvent probe with a diameter of ∼1.4 Å. For the calculation of the ligand volume, only those ligand atoms located within the pore were included (atom diameter, ∼1.4 Å). All calculations were carried out using the program VOLUMES (R.M. Esnouf, unpublished computer program, personal communication).

Characterization of the Lipid Ligand by Mass Spectrometry

Concentrated purified ORF-9b protein was added to a chloroform-water two-phase mixture and vortexed. After a 5 min equilibration at room temperature, the hydrophilic phase was removed. The hydrophobic phase containing the ligand molecule was diluted into a mixture of chloroform, methanol, and water (10:10:3) and analyzed by positive ion electrospray mass spectrometry on a Waters-Micro Q-TOF mass spectrometer.

Purification under Denaturing Conditions, Refolding, and Biophysical Experiments

ORF-9b protein was expressed in E. coli as described in Experimental Procedures. The protein was then purified under denaturing conditions as follows: cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 1% Tween-20, 10 mM imidazole. The cells were lysed by sonication and the sample was clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min. To the supernatant, 2 ml of Ni-NTA superflow (Qiagen) was added and the sample was stirred for 2 hr at 4°C. The Ni-NTA beads were then washed with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and protein was eluted in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole.

The protein was refolded by rapid dilution into 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 M L-arginine, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride and incubated for 24 hr at 4°C. The refolding mixture was then concentrated and purified by gel filtration in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences). The elution position of refolded ORF-9b was identical to that of natively purified protein.

Mass spectrometry analysis confirmed that refolded ORF-9b contained only trace amounts of the lipid ligand (data not shown). Dynamic light scattering revealed that both refolded and natively purified protein have similar hydrodynamic behavior (Rhnatively purified = 2.27; Rhrefolded = 2.23) and analytical ultracentrifugation of refolded ORF-9b gave a profile similar to that shown in Supplemental Data.

To test the effect of the lipid removal on the stability of the protein, we carried out a ThermoFluor assay (Lo et al., 2004, Pantoliano et al., 2001). In this experiment, ORF-9b was heated from 20°C to 95°C in the presence of a fluorescent dye, SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes). As the protein unfolds, hydrophobic residues become solvent exposed, leading to an increase in the fluorescence of the dye, measured in a real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad Opticon 2).

ORF-9b Expression in Mammalian Cells

N- and C-terminally hexahistidine-tagged ORF-9b constructs were prepared by PCR and subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pLEXm (Aricescu et al., 2006) for transient expression tests. For the subcellular localization analysis, the ORF-9b constructs were transfected into COS7 cells grown on four-well BD Falcon glass culture slides (BD Biosciences) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). The cells were processed for immunofluorescence 48 hr later. Briefly, the procedure was as follows: cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked with a mixture of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.25% Triton X-100 (all solutions were made in PBS [pH 7.4], and all incubations were done at room temperature). The His-tagged ORF-9b was detected using the penta-His Alexa Fluor 555 monoclonal antibody (Qiagen) diluted 1:150 in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.05% Triton X-100. The slides were washed, mounted in FluorSave reagent (Calbiochem), and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000U inverted microscope. Differential interference contrast and epifluorescence images were taken using a 60× oil objective with a Hamamatsu Orca 285 CCD camera and processed with IP Lab imaging software.

ORF-9b expression was also analyzed by Western blotting. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the ORF-9b His-tagged constructs, collected 48 hr later, and lysed by repeated passage through a 22G needle and centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 g. Samples were loaded in a 15% acrylamide gel, separated by SDS-PAGE, and electroblotted onto a Hybond-C nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology). The membrane was blocked overnight in 5% skimmed dry milk in PBS and probed for 1 hr at room temperature with the penta-His monoclonal antibody (Qiagen; 1:1000 dilution). The secondary antibody used was goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc-specific) horseradish peroxidase (Sigma; 1:2000 dilution). Chemiluminescence detection was performed using the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology).

Figures

Figures were generated with Bobscript (Esnouf, 1997) and PyMOL (DeLano, 2002) and rendered with POV-Ray (Persistence of Vision Ltd., Williamstown, Victoria, Australia).

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Walsh and the staff of BM14, the UK MAD beamline at Grenoble, for assistance, Robert Esnouf and Karl Harlos for help with X-ray data collection, Joanne Nettleship for assistance with mass spectrometry, the Structural Genomics Consortium for access to analytical ultracentrifugation equipment, and Stuart Siddell and Andrew Davidson for helpful discussions. C.M. is funded by a Wellcome Trust studentship. A.R.A. is supported by Cancer Research UK, J.M.G. and R.J.C.G. by the Royal Society, and D.I.S. and the Oxford Protein Production Facility by the UK Medical Research Council and European Commission grant number QLG2-CT-2002-00988 (SPINE).

Published: July 18, 2006

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include analytical ultracentrifugation results and sequence alignments and are available with this article online at http://www.structure.org/cgi/content/full/14/7/1157/DC1/.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates and structure factors of SARS-CoV ORF-9b have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), ID code 2CME.

Supplemental Data

References

- Aricescu A.R., Lu W., Jones E.Y. A time- and-cost efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006 doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Clore G.M., DeLano W.L., Gros P.N., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Jiang J.-S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N.S. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.K., Sue S.C., Yu T.H., Hsieh C.M., Tsai C.K., Chiang Y.C., Lee S.J., Hsiao H.H., Wu W.J., Chang C.F., Huang T.H. The dimer interface of the SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein adapts a porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus-like structure. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5663–5668. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.K., Sue S.C., Yu T.H., Hsieh C.M., Tsai C.K., Chiang Y.C., Lee S.J., Hsiao H.H., Wu W.J., Chang W.L. Modular organization of SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. J. Biomed. Sci. 2005;13:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9035-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie W.W. Second Edition. Pergamon; Oxford: 1982. Lipid Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot N., van Dijk E., Babajko S., Seraphin B. ‘Cap-tabolism.’. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. General quadratic functions in real and reciprocal space and their application to likelihood phasing. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2000;56:1612–1621. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900013263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan C.A., Rottier P.J. Molecular interactions in the assembly of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2005;64:165–230. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(05)64006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Fortelle E., Bricogne G. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for the multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly C., Ghani A., Leung G., Hedley A., Fraser C., Riley S., Abu-Raddad L., Ho L., Thach T., Chau P. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst H., Shatkin A.J. Reovirus hemagglutinin mRNA codes for two polypeptides in overlapping reading frames. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnouf R.M. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1997;15:132–134. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filman D.J., Syed R., Chow M., Macadam A.J., Minor P.D., Hogle J.M. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 1989;8:1567–1579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer F., Peng D., Hingley S.T., Weiss S.R., Masters P.S. The internal open reading frame within the nucleocapsid gene of mouse hepatitis virus encodes a structural protein that is not essential for viral replication. J. Virol. 1997;71:996–1003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.996-1003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadola S.D., Zaccai N.R., Harlos K., Shepherd D., Castro-Palomino J.C., Ritter G., Schmidt R.R., Jones E.Y., Cerundolo V. Structure of human CD1b with bound ligands at 2.3 Å, a maze for alkyl chains. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:721–726. doi: 10.1038/ni821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C., Blumberg B.M., Kolakofsky D. Sendai virus contains overlapping genes expressed from a single mRNA. Cell. 1983;35:829–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D.I., Metoz F. ESPript: multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.E., Hope T.J. RNA export: insights from viral models. Essays Biochem. 2000;36:115–127. doi: 10.1042/bse0360115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L., Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout D.R., Mulcahy E.R., Pacyniak E., Gomez L.M., Gomez M.L., Stephens E.B. Vpu: a multifunctional protein that enhances the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Curr. HIV Res. 2004;2:255–270. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Yu L., Petros A.M., Gunasekera A., Liu Z., Xu N., Hajduk P., Mack J., Fesik S.W., Olejniczak E.T. Structure of the N-terminal RNA-binding domain of the SARS CoV nucleocapsid protein. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6059–6063. doi: 10.1021/bi036155b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S.J., Campbell S.F., Thornton J.M. Molecular recognition. Conformational analysis of limited proteolytic sites and serine proteinase protein inhibitors. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;220:507–530. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R.J. A comparative view of initiation site selection mechanisms. In: Hershey J.W.B., Mathews M.B., Sonenberg N., editors. Translational Control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1996. pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs B.L., Samuel C.E. Biosynthesis of reovirus-specified polypeptides: the reovirus s1 mRNA encodes two primary translation products. Virology. 1985;143:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.G., Sohn E.J., Seo J., Lee K.J., Lee H.S., Hwang I., Whiteway M., Sacher M., Oh B.H. Crystal structure of bet3 reveals a novel mechanism for Golgi localization of tethering factor TRAPP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:38–45. doi: 10.1038/nsmb871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E., Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek T., Erdman D., Goldsmith C., Zaki S., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J., Lim W. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesk A. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. Introduction to Protein Science: Architecture, Function, and Genomics. [Google Scholar]

- Lo M.C., Aulabaugh A., Jin G., Cowling R., Bard J., Malamas M., Ellestad G. Evaluation of fluorescence-based thermal shift assays for hit identification in drug discovery. Anal. Biochem. 2004;332:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra M., Jones S., Astell C., Holt R., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y., Khattra J., Asano J., Barber S., Chan S. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo C.J., Diprose J.M., Walter T.S., Berry I.M., Wilson J., Owens R.J., Jones E.Y., Harlos K., Stuart D.I., Esnouf R.M. Benefits of automated crystallization plate tracking, imaging, and analysis. Structure. 2005;13:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight S., Tjian R. Transcriptional selectivity of viral genes in mammalian cells. Cell. 1986;46:795–805. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee D.E. XtalView/Xfit—a versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J. Struct. Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami M., Orito E., Ohba K., Ikeo K., Lau J.Y., Gojobori T. Constrained evolution with respect to gene overlap of hepatitis B virus. J. Mol. Evol. 1997;44:S83–S90. doi: 10.1007/pl00000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoliano M.W., Petrella E.C., Kwasnoski J.D., Lobanov V.S., Myslik J., Graf E., Carver T., Asel E., Springer B.A., Lane P., Salemme F.R. High-density miniaturized thermal shift assays as a general strategy for drug discovery. J. Biomol. Screen. 2001;6:429–440. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape T., Schneider T.R. HKL2MAP: a graphical user interface for phasing with SHELX programs. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2004;37:843–844. [Google Scholar]

- Pongoski J., Asai K., Cochrane A. Positive and negative modulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev function by cis and trans regulators of viral RNA splicing. J. Virol. 2002;76:5108–5120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5108-5120.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M., Shi Y., Guo Z., Chen Z., He R., Chen R., Zhou D., Dai E., Wang X., Si B. Antibody responses to individual proteins of SARS coronavirus and their neutralization activities. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota P., Oberste M., Monroe S., Nix W., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel C.E. Polycistronic animal virus mRNAs. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1989;37:127–153. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60697-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T.R., Sheldrick G.M. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake S.D., Brian D.A. Bovine coronavirus I protein synthesis follows ribosomal scanning on the bicistronic N mRNA. Virus Res. 1997;48:101–105. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(96)01423-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M.W., Choppin P.W., Lamb R.A. A previously unrecognized influenza B virus glycoprotein from a bicistronic mRNA that also encodes the viral neuraminidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:4879–4883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G.M. Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Z. Kristallogr. 2002;217:644–650. [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Dobbe J.C., Thiel V., Ziebuhr J., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Rozanov M., Spaan W.J., Gorbalenya A.E. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N., Dever T.E. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors and regulators. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler K., Masignani V., Eickmann M., Becker S., Abrignani S., Klenk H.D., Rappuoli R. SARS—beginning to understand a new virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:209–218. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton G., Fry E., Carter L., Sainsbury S., Walter T.S., Nettleship J., Berrow N., Owens R., Gilbert R., Davidson A. The nsp9 replicase protein of SARS-coronavirus, structure and functional insights. Structure. 2004;12:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli P., Trono D. Editing at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Science. 2005;307:1061–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.1105964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter T.S., Diprose J.M., Mayo C.J., Siebold C., Pickford M.G., Carter L., Sutton G.C., Berrow N.S., Brown J., Berry I.M. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:651–657. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willbold D., Hoffmann S., Rosch P. Secondary structure and tertiary fold of the human immunodeficiency virus protein U (Vpu) cytoplasmic domain in solution. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;245:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.