Abstract

Viruses in the genus Coronavirus are currently placed in three groups based on antigenic cross-reactivity and sequence analysis of structural protein genes. Consensus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers were used to obtain cDNA, then cloned and sequenced a highly conserved 922 nucleotide region in open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the polymerase (pol) gene from eight coronaviruses. These sequences were compared with published sequences for three additional coronaviruses. In this comparison, it was found that nucleotide substitution frequencies (per 100 nucleotides) varied from 46.40 to 50.13 when viruses were compared among the traditional coronavirus groups and, with one exception (the human coronavirus (HCV) 229E), varied from 2.54 to 15.89 when compared within these groups. (The substitution frequency for 229E, as compared to other members of the same group, varied from 35.37 to 35.72.) Phylogenetic analysis of these pol gene sequences resulted in groupings which correspond closely with the previously described groupings, including recent data which places the two avian coronaviruses—infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) of chickens and turkey coronavirus (TCV)—in the same group [Guy, J.S., Barnes, H.J., Smith L.G., Breslin, J., 1997. Avian Dis. 41:583–590]. A single pair of degenerate primers was identified which amplify a 251 bp region from coronaviruses of all three groups using the same reaction conditions. This consensus PCR assay for the genus Coronavirus may be useful in identifying as yet unknown coronaviruses.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Polymerase gene, Consensus PCR

The genus Coronavirus is in the family Coronaviridae in the order Nidovirales (Cavanagh, 1997). Viruses of this order have linear, non-segmented, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genomes with similar genomic organization and a nested set of subgenomic mRNAs. Members of the genus Coronavirus infect birds and mammals, causing respiratory, enteric, cardiovascular and neurological disease (Holmes and Lai, 1996). The coronaviruses were originally divided into three groups based on antigenic relatedness of the structural proteins (Sturman and Holmes, 1983, Siddell, 1995), which include the haemagglutinin-esterase (HE), spike (S), integral membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. Genes encoding these proteins are clustered at the 3′ end of the 27–31 kb coronavirus genome. However, the most highly conserved genomic sequences are found in the 20 kb polymerase (pol) gene, which covers the 5′ two-thirds of the coronavirus genome (Snijder and Spaan, 1995). The pol gene contains two large open reading frames (ORFs), ORF 1a and ORF 1b. Within ORF 1b, there are very highly conserved regions encoding conserved functions (e.g. polymerase and helicase activity) which, combined with similarities in replication and expression strategies, demonstrate an evolutionary link among coronaviruses, arteriviruses, and toroviruses. These similarities form the rationale for placing these viruses in the order Nidovirales (Snijder et al., 1990, Snijder et al., 1991, den Boon et al., 1991, Godeny et al., 1993, Snijder and Spaan, 1995, Cavanagh, 1997). Therefore, the highly conserved structure and function of viral polymerases make the pol a logical region for making phylogenetic comparisons, as well as for developing a consensus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay which could be used for the identification of novel coronaviruses. This strategy has been used with other viruses, particularly papillomaviruses (Bernard et al., 1994, Astori et al., 1997). Such an assay would be useful because possible novel coronaviruses have been tentatively identified (e.g. using electron microscopy) in association with a variety of human and animal diseases, but further characterization and definitive identification of these agents as coronaviruses has been difficult (Resta et al., 1985, Myint, 1995, Guy et al., 1997).

For these reasons a highly conserved 922 nucleotide region in ORF 1b of the pol gene of eight coronaviruses were recently cloned and sequenced using consensus PCR primers. This region has previously been completely sequenced for two group 1 viruses, human coronavirus (HCV)-229E (Herold et al., 1993) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) of swine (Elequet et al., 1995), two different isolates of a single group 2 virus, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (Pachuk et al., 1989, Lee et al., 1991), and the single group 3 virus, infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) of chickens (Boursnell et al., 1987). Degenerate oligonucleotide primers were selected by identifying the most conserved regions from the published IBV and MHV pol sequences (Boursnell et al., 1987, Lee et al., 1991). These primers were used to derive clones from three group 1 viruses—feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV; UCD2 strain provided by Nils Pedersen, University of California, Davis), TGEV of swine (provided by David Brian, University of Tennessee, Knoxville) and canine coronavirus (CCV; 1–71 strain from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), catalog no. VR-809, Rockville, MD), and five group 2 viruses, hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus of swine (HEV; ATCC catalog no. VR-741), bovine coronavirus (BCV) (provided by David Brian), HCV-OC43 (provided by Ortwin Schmidt, University of Oklahoma School of Osteopathic Medicine, Tulsa), sialodacryoadenitis virus of rats (SDAV; provided by Trenton Schoeb, University of Florida, GA, from a stock originally derived from ATCC) and turkey enteric coronavirus (TCV) obtained directly from ATCC (ATCC VR-911). Two genome-sense primers were used in the PCR reactions. The 5′-most primer was 8p, 5′-TATGA(GA)GG(TC)GG(GC)TGTATACC-3′, the 5′ end of which was 52 nucleotides upstream from the second genome-sense primer 1Ap, 5′-GATAAGAGTGC(TA)GGCTA(TC)CC-3′. One antigenome-sense primer was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis and for the subsequent PCR; 7m, 5′-ACTAGCATTGT(AG)TGTTG(AT)GAACA-3′. The region amplified by these primers (1Ap/7m) (including the primer sequences) corresponds to nucleotides 13 833 through 14 797 of IBV (Boursnell et al., 1987) and 15 118 through 16 082 of MHV (Lee et al., 1991). The 1Ap/7m primer combination, which produced a 965 bp product, was used for all of the indicated viruses except for HEV and TCV. For these viruses, the 8p/7m primer combination was used, which produced a 1013 bp product. The 922 nucleotides internal to the 1Ap/7m primers (919 in the case of IBV and TCV, which contain a three nucleotide deletion) were sequenced and analysed. These primers were also used in an attempt to characterize the putative rabbit coronavirus (RbCV), which was first described from rabbits with pleural effusion disease and has tentatively been considered a coronavirus (Small et al., 1979). However, this classification is not definitive (Siddell, 1995) and the virus is poorly characterized. The primer pairs (1Ap/7m, 8p/7m) did not amplify any identifiable sequences from a standard infectious serum (ATCC VR-920) derived from a rabbit with pleural effusion disease.

Viral RNA was prepared (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987) from tissue culture supernatants or cellular extracts. First strand cDNA was synthesized using avian myeloblastoma virus reverse transcriptase (RT, Promega, Madison, WI) or Maloney murine leukemia virus RT (SuperscriptI or II, Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, MD). PCR was performed with 0.25 μM primers, from 0.025 to 0.04 U/μl Taq polymerase (Promega), manufacturer’s buffer containing 1.5 mM Mg, and deoxynucleotide triphosphates (0.1 mM each). PCR profiles involved an initial denaturation for 1 min at 98°C followed by 32–40 cycles of annealing at 45°C for 1 to 2 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min, and melting at 94°C for 1 min. In some cases, the final 20 cycles were performed using a 50°C annealing temperature. Amplification products were subcloned into the pCR1000 or 2000 vector using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Inserts were sequenced completely in both directions with Sequenase 2.0 (US Biochemical, Cleveland, OH), plasmid region primers, the PCR primers, and additional sequencing primers (not shown). Sequence alignment was performed using the Lineup and Pileup programs from the Genetics Computer Group software (Devereux et al., 1984).

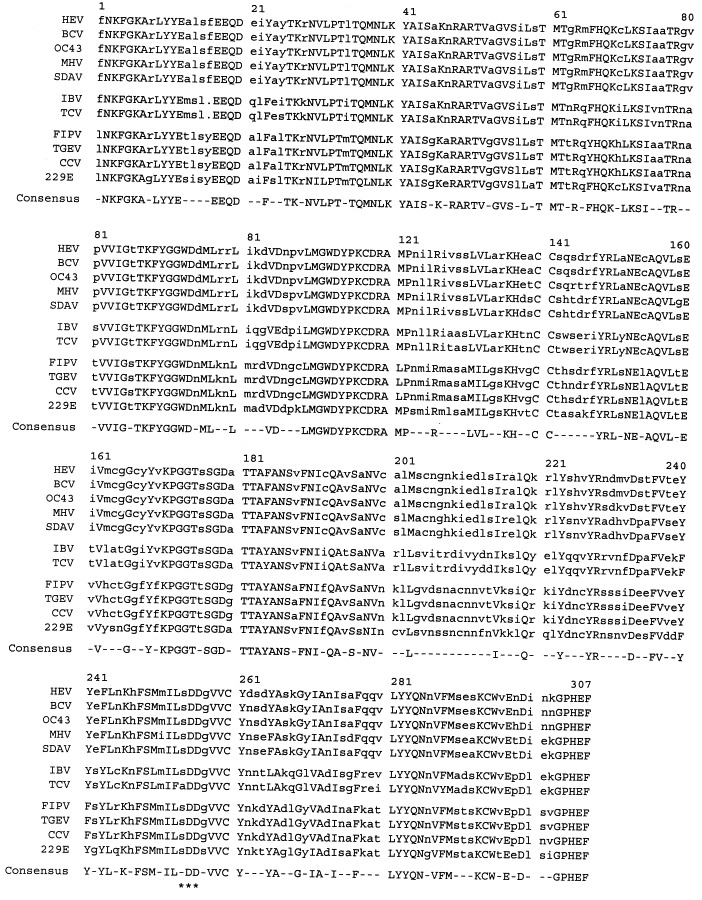

The deduced amino acid sequences for this region of ORF 1b of the pol gene for the 11 coronaviruses align precisely (Fig. 1 ) and correspond to the highly conserved region surrounding the SDD or GDD polymerase motif common to viral RNA-dependent polymerases (Poch et al., 1989). The only gaps in the alignment are attributable to a single amino acid deletion at position 16 in both IBV and TCV. All coronaviruses show the SDD sequence at the putative active site of the polymerase, except TCV, which, unusually for a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, has an ADD sequence. The percent amino acid and nucleotide sequence identities among these 11 viruses are shown in Table 1 and reveal identities which are similar to the patterns described by the three groups, with the single exception that the TCV sequence is much more similar to IBV than to any other coronavirus. For example, within the group 2 cluster of five viruses the maximum substitution frequency is 16/100 nucleotides (comparing MHV to HEV) while among the four group 1 viruses the frequency among CCV, FIPV and CCV is <5/100 nucleotides. However, 229E differs from these three by an average of 36 substitutions/100 nucleotides, which is consistent with the weaker antigenic relationship of 229E to these viruses (Sanchez et al., 1990). The TCV sequence is very similar to IBV, showing a substitution frequency of only 7.2/100 nucleotides, clearly suggesting that these viruses should fall within the same group.

Fig. 1.

Deduced amino acid sequence of the polymerase motif region from open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the pol gene of 11 coronaviruses. The mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) and 229E sequences are derived from published sequences (see text). The first amino acid in this figure corresponds to amino acid 466 of the IBV ORF 1b (Lee et al., 1991). Amino acids 79 through 307 correspond to 228 of the 258 amino acids representing the conserved polymerase motif common to coronaviruses, toroviruses and arteriviruses (see Fig. 5 in den Boon et al., 1991). The highly conserved SDD or GDD polymerase motif (Poch et al., 1989) is identified by asterisks. Capitalized letters indicate amino acids which are conserved in all 11 sequences.

Table 1.

Amino acid (italics; on top, right-hand side) and nucleotide substitution rates (per 100 residues) in a highly conserved region of open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the pol gene of 11 coronaviruses

| HEV | BCV | OC43 | MHV | SDAV | IBV | TCV | FIPV | TGEV | CCV | 229E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEV | 0.98 | 2.99 | 8.27 | 7.19 | 38.38 | 40.56 | 44.90 | 45.48 | 44.32 | 48.45 | |

| BCV | 2.54 | 1.98 | 8.27 | 7.19 | 38.38 | 40.56 | 43.75 | 44.32 | 43.18 | 48.45 | |

| OC43 | 3.21 | 3.33 | 9.01 | 7.91 | 38.38 | 40.56 | 44.90 | 44.90 | 44.32 | 48.45 | |

| MHV | 15.89 | 15.09 | 15.35 | 0.98 | 38.92 | 41.11 | 47.85 | 47.85 | 47.85 | 50.28 | |

| SDAV | 14.16 | 13.51 | 14.03 | 4.12 | 37.84 | 40.01 | 46.65 | 46.65 | 46.65 | 49.05 | |

| IBV | 49.50 | 49.08 | 48.25 | 49.50 | 47.01 | 3.00 | 45.68 | 46.27 | 45.68 | 47.46 | |

| TCV | 49.92 | 49.92 | 48.66 | 50.13 | 48.04 | 7.19 | 47.46 | 48.06 | 47.46 | 49.28 | |

| FIPV | 50.11 | 49.06 | 49.90 | 49.69 | 47.82 | 46.40 | 48.25 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 24.03 | |

| TGEV | 49.06 | 48.85 | 48.65 | 49.27 | 48.03 | 47.63 | 48.87 | 3.33 | 0.65 | 24.48 | |

| CCV | 48.23 | 47.82 | 48.03 | 49.27 | 47.00 | 47.22 | 49.92 | 4.01 | 4.58 | 24.48 | |

| 229E | 49.48 | 48.44 | 48.44 | 50.54 | 49.69 | 48.87 | 48.04 | 35.37 | 35.72 | 35.54 |

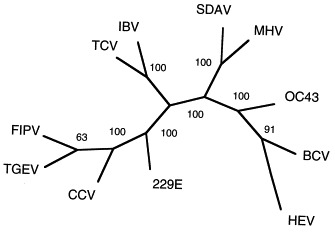

To further characterize the phylogenetic relationships among these viruses, a dendogram was created with PAUP (version 3.0) using the maximum parsimony method. A branch and bond algorithm was used to identify the single most parsimonious tree. Only one tree was identified. The three nucleotides missing in the IBV and TCV sequences (which represent a single amino acid deletion) were each treated as a separate character state rather than as missing data. The resulting unrooted tree is shown in Fig. 2 . The consistency index of the tree was 0.818 and the rescale consistency index was 0.711. Bootstrap analysis was also performed and the resulting values are shown at branch points in the figure. An identical tree and essentially identical bootstrap values were also derived using the Kimura two-parameter method for calculating distances and the neighbor-joining method to construct the tree (using the Clustal W program). Again, this analysis reveals that published IBV sequence and the TCV sequence presented here are very closely related. In addition, the three group I viruses FIPV, TGEV and CCV are found on a common branch with HCV-229E being more distantly related. The group 2 viruses fall into two groupings, with SDAV and MHV being closely related to one another and the remaining three viruses in this group—HCV-OC43, BCV and HEV forming a separate branch.

Fig. 2.

Unrooted dendogram showing Kimura’s distances (represented by branch lengths) for cDNA sequences from a 922 nucleotide region of open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the pol gene of 11 coronaviruses (see text for details). Numbers represent the results of a bootstrap analysis and indicate the number of times out of 100 iterations that these branch points were identified. Sequence for the eight coronavirus sequences reported here is available from GenBank under the following accession numbers: bovine coronavirus (BCV), AF124985; canine coronavirus (CCV), AF124986; feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), AF124987; hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus of swine (HEV), AF124988; OC43, AF124989; sialodacryoadenitis virus of rats (SDAV), AF124990; turkey coronavirus (TCV), AF124991; transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), AF124992.

This phylogenetic analysis conforms closely to results from antigenic studies of these coronaviruses, with the single exception that the analysis indicates that TCV and IBV are closely related viruses. Coronaviruses have traditionally been divided into three groups (Sturman and Holmes, 1983, Siddell, 1995), including two groups of primarily mammalian coronaviruses (groups 1 and 2, although TCV was recently included in group 2, Siddell, 1995) and a separate, single-member group for the avian coronavirus IBV (group 3). The antigenic characterization of the second avian coronavirus, TCV, has been controversial. Serologic studies (Dea and Tijssen, 1989, Dea et al., 1990) and sequence analysis of the N and M genes (Verbeek and Tijssen, 1991) from a cell culture-adapted clone of the Minnesota strain of TCV indicate that TCV is closely related to the group 2 mammalian coronaviruses, particularly BCV and HCV-OC43. However, recent serologic studies with both polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (Guy et al., 1997) indicate that the Minnesota strain of TCV, as well as additional field isolates of TCV, are close antigenic relatives of IBV. The data agree with this latter conclusion. Since the pol gene product is not involved in the determination of antigenic cross-reactivity among viruses, the data do not directly address the discrepancy between the results of Guy et al. (1997) and Dea et al. (1990), but do indicate that further work is necessary to resolve the contradictory finding with regard to the characterization of TCV.

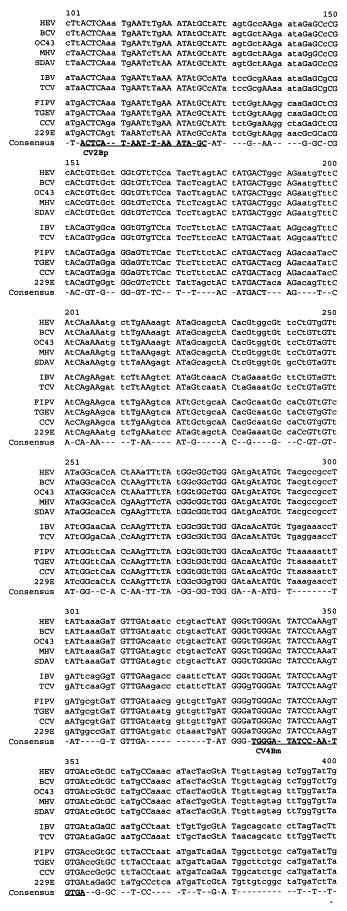

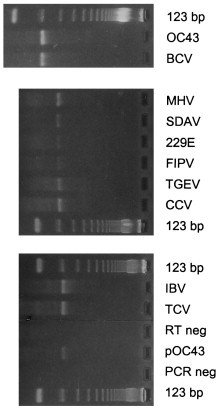

A goal of the sequence analysis described above was to identify conserved regions which could be targeted for the development of a consensus PCR assay for the genus Coronavirus. Since neither primer pair used in cloning these pol gene regions (1Ap/7m or 8p/7m) detected all 11 coronaviruses used in this study, the 922 (919 in the case of IBV and TCV) nucleotide region internal to the 1Ap/7Bm primers was compared to identify regions with greater sequence identity. As shown in Fig. 3 , two regions were selected to serve as targets for two degenerate oligonucleotide primers: primer 2Bp, 5′-ACTCA(A/G)(A/T)T(A/G)AAT(T/C)TNAAATA(T/C)GC-3′; and primer 4Bm, 5′-TCACA(C/T)TT(A/T)GGATA(G/A)TCCCA-3′. After testing different reaction conditions, a protocol was selected in which the RT and PCR portions of the assay were performed essentially as described above, using the 4Bm oligonucleotide to prime cDNA synthesis. Annealing conditions during the PCR assay were also modified slightly from those described above, namely: in the first five cycles the annealing temperature was 40°C (2 min), followed by 35 cycles at 50°C (1.5 min). The sensitivity of this protocol was tested using a plasmid containing the 965 bp HCV-OC43 pol sequence. The limit of detection for this plasmid on an ethidium bromide-stained gel was 6000 plasmid copies (data not shown). Then this assay was tested on representative coronaviruses from each group. As shown in Fig. 4 , these primers amplified the expected 251 bp region in four group 1 viruses (229E, FIPV, TGEV, CCV), four group 2 viruses (OC43, BCV, MHV, SDAV), the single, currently recognized, group 3 virus (IBV), and TCV, which is currently placed in group 2. In addition, these primers detected a fifth group 2 virus, HEV (data not shown). After repeated attempts, these primers did not detect the pol target sequence in infectious serum from a rabbit with pleural effusion disease (containing 4×105 rabbit infectious units; ATCC VR-920). Thus this assay will detect all ten of the well-characterized coronaviruses studied here, will also detect TCV, but will not detect the putative RbCV. This result suggests that the putative RbCV is not a member of the genus Coronavirus. However, slight variations in the target sequences for these primers, or a lack of sensitivity of this assay, could also explain this negative result.

Fig. 3.

cDNA sequences for a subregion of the 922 nucleotides from open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the pol gene used for the analysis shown in Fig. 2. (Nucleotide number 1 of this 922 nucleotide-long region corresponds to nucleotide number 13 853 in the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) pol sequence (Boursnell et al., 1987). This Figure shows nucleotides number 101 through 400. The regions targeted by the two degenerate primers (CV2Bp and CV4Bm, see text for sequence) used in the consensus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for the genus Coronavirus are underlined.

Fig. 4.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products for ten coronaviruses [OC43, bovine coronavirus (BCV), mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), sialodacryoadenitis virus of rats (SDAV), 229E, feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), canine coronavirus (CCV), infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), turkey coronavirus (TCV)] using the consesus PCR primers (2Bp and 4Bm, see text for sequence) for the genus Coronavirus. Twenty μl of reaction product were run on a 4% agarose gel (NuSieve 3:1, FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) and stained with 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide. Also included on the gel were: reaction product from PCR using 1 pg of plasmid containing target sequence from human coronavirus (HCV)-OC43 as positive control (pOC43); reaction products from negative control samples (water only) which were carried through both the reverse transcriptase (RT) and PCR steps (RT neg) or the PCR step alone (PCR neg); 1 μg of 123 bp molecular size standards (Bethesda Research Labs, Bethesda, MD).

Coronaviruses infect a variety of animal hosts and many uncharacterized coronaviruses have been implicated in a variety of diseases, particularly enteric (Resta et al., 1985, Guy et al., 1997) and respiratory (Myint, 1995) infections. The consensus PCR approach described here has already provided novel information on the identity of one little-studied coronavirus (TCV), suggesting that it should be classified with IBV in group 3. In the future, this consensus PCR approach should prove useful in identifying and characterizing additional members of the genus Coronavirus.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Public Health Service Grant P40 RR00463 and by a grant from the Thrasher Research Fund. We thank Ms Sharon Blount for technical assistance and Drs Thomas R. Uunasch and Elliot J. Lefkowitz for assistance with preparation of the dendrogram.

References

- Astori, G., Arzese, A., Pipan, C., de Villiers, E.M., Botta, G.A., 1997. Characterization of a putative new HPV genomic sequence from a cervical lesion using L1 consensus primers and restriction fragment length polymorphism. Virus Res. 50, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernard, H.U., Chan, S.Y., Manos, M.M., Ong, C.K., Villa, L.L., Delius, H., Peyton, C.L., Bauer, H.M., Wheeler, C.M., 1994. Identification and assessment of known and novel human papillomaviruses by polymerase chain reaction amplification, restriction fragment length polymorphisms, nucleotide sequence, and phylogenetic algorithms [see comments] [published erratum appears in J. Infect. Dis. 1996 Feb;173 (2):516]. J. Infect. Dis. 170, 1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boursnell M.E.G., Brown T.T.K., Foulds I.J., Green P.D., Tomley F.M., Binns M.M. Completion of the sequence of the genome of the coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1987;68:57–77. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch. Virol. 1997;142:629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by guanidiniumthiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea S., Tijssen P. Detection of turkey enteric coronavirus by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and differentiation from other coronaviruses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1989;50:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea S., Verbeek A.J., Tijssen P. Antigenic and genomic relationships among turkey and bovine enteric coronaviruses. J. Virol. 1990;64:3112–3118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3112-3118.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon J.A., Snijder E.J., Chirnside E.D., DeVries A.A.F., Horzinek M.C., Spaan W.J.M. Equine arteritis virus in not a togavirus but belongs to the coronavirus superfamily. J. Virol. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J., Haeberli P., Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acid Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elequet J.F., Rasschaert D., Lambert P., Levy L., Vende P., Laude H. Complete sequence (20 kilobases) of the polyprotein-encoding gene 1 of transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Virology. 1995;206:817–822. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godeny E.K., Chen L., Kumar S.N., Methven S.L., Koonin E.V., Brinton M.A. Complete genomic sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus LDV. Virology. 1993;194:585–596. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy J.S., Barnes H.J., Smith L.G., Breslin J. Antigenic characterization of a turkey coronavirus identified in poult enteritis- and mortality syndrome-affected turkeys. Avian Dis. 1997;41:583–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold J., Raabe T., Schelle-Prinz B., Siddell S.G. Nucleotide sequence of the human coronavirus 229E RNA polymerase locus. Virology. 1993;195:680–691. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K.V., Lai M.M. Coronaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B.N., Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Virology. 3r edition. Raven Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.J., Shieh C.K., Gorbalenya A.E., Koonin E.V., LaMonica N., Tuler J., Bagdzhadzhyan A., Lai M.M.C. The complete sequence (22 kilobases) of murine coronavirus gene 1 encoding the putative proteases and RNA polymerase. Virology. 1991;180:567–582. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90071-I. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint S.H. Human coronavirus infections. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Pachuk C.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Zoltick P.W., Spaan W.J.M., Weiss S.R. Molecular cloning of the gene encoding the putative polymerase of mouse hepatitis coronavirus, strain A59. Virology. 1989;171:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poch O., Sauvaget O.I., Delarue M., Tordo N. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 1989;8:3867–3874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta S., Luby J.P., Rosenfeld C.R., Siegel J.D. Isolation and propagation of a human enteric coronavirus. Science. 1985;229:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.2992091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C.M., Jimenez G., Laviada M.D., Correa I., Sune C., Bullido M.J., Gebauer F., Smerdou C., Callebaut P., Escribano J.M., Enjuanes L. Antigenic homology among coronaviruses related to transmissible goastroenteritis virus. Virology. 1990;174:410–417. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddell S.G. The coronaviridae: an introduction. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Small J.D., Aurelian L., Squire R.A., Strandberg J.D., Melby E.C., Jr., Turner T.B., Newman B. Rabbit cardiomyopathy associated with a virus antigenically related to human coronavirus strain 229E. Am. J. Pathol. 1979;95:709–729. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., Spaan W.M.J. The coronavirus-like superfamily. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., den Boon J.A., Bredenbeek P.J., Horzinek M.C., Rijnbrand R., Spaan W.J. The carboxyl-terminal part of the putative Berne virus polymerase is expressed by ribosomal frameshifting and contains sequence motifs which indicate that toro- and coronaviruses are evolutionarily related. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4535–4542. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., den Boon J.A., Horzinek M.C., Spaan W.J.M. Comparison of the genome organization of toro- and coronaviruses: evidence for two nonhomologous RNA recombination events during Berne virus evolution. Virology. 1991;180:448–452. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90056-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman L.S., Holmes K.V. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1983;28:35–112. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek A., Tijssen P. Sequence analysis of the turkey enteric coronavirus nucleocapsid and membrane protein genes: a close genomic relationship with bovine coronavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:1659–1666. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]