Graphical abstract

Inhibitory activity appeared to be associated with the presence of an apigenin moiety at position C-3′ of flavones, as biflavonoid had an effect on SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity.

Abbreviations: SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; CoV, coronavirus; IC50, concentration producing a 50% reducing in activity; Ki, inhibition constant; Vmax, maximum velocity; Km, Michaelis-Menten constant; RFUs, relative fluorescence units

Keywords: SARS-CoV 3CLpro, Torreya nucifera, Biflavonoid, Amentoflavone

Abstract

As part of our search for botanical sources of SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors, we selected Torreya nucifera, which is traditionally used as a medicinal plant in Asia. The ethanol extract of T. nucifera leaves exhibited good SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity (62% at 100 μg/mL). Following bioactivity-guided fractionation, eight diterpenoids (1–8) and four biflavonoids (9–12) were isolated and evaluated for SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition using fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis. Of these compounds, the biflavone amentoflavone (9) (IC50 = 8.3 μM) showed most potent 3CLpro inhibitory effect. Three additional authentic flavones (apigenin, luteolin and quercetin) were tested to establish the basic structure–activity relationship of biflavones. Apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin inhibited 3CLpro activity with IC50 values of 280.8, 20.2, and 23.8 μM, respectively. Values of binding energy obtained in a molecular docking study supported the results of enzymatic assays. More potent activity appeared to be associated with the presence of an apigenin moiety at position C-3′ of flavones, as biflavone had an effect on 3CLpro inhibitory activity.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a contagious and often fatal respiratory illness, was first reported in Guandong province, China, in November 2002.1, 2 Its rapid and unexpected spread to other Asian countries, North America, and Europe alarmed both the public and the World Health Organization (WHO). SARS is caused by the novel coronavirus (CoV), SARS-CoV.3, 4 SARS-CoV is a positive-strand RNA virus whose genome sequence exhibits only moderate homology to other known coronaviruses.5 SARS-CoV encodes a chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), which is also called the main protease (Mpro) because it plays a pivotal role in processing viral polyproteins and controlling replicase complex activity.6 This enzyme is indispensable for viral replication and infection processes, thereby making it an ideal target for the design of antiviral therapies. The 3CL active site contains a catalytic dyad in which a cysteine residue (Cys145) acts as a nucleophile and a histidine residue (His41) acts as the general acid-base.6 To date, SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors have been reported from both synthetic peptidyl compound libraries and natural product derived libraries.7 Inhibitory synthetic compounds include C2-symmetric diols,8 quinolinecarboxylic acids,9 isatins,10 and anilides.11 Natural-derived inhibitors include betulinic acid,12 indigo,13 aloeemodin,13 luteolin,7 and quinine-methide triterpenoids; the latter are products of our latest investigation 3CLpro inhibitor from Tripterygium regelii.14 These natural molecules were found to have IC50 values ranging from 3 to 300 μM in the enzyme assays.

As part of an ongoing investigation of potential SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors from medicinal plants, we performed an initial screen of ethanol extracts of the leaves of Torreya nucifera using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay. T. nucifera, a Taxaceae tree found in snowy areas near the Sea of Jeju Island in Korea that has been used in traditional Asian medicine as a remedy for stomachache, hemorrhoids, and rheumatoid arthritis, was chosen as the starting material by virtue of its observed 3CLpro inhibition (62% at 100 μg/mL). We isolated 12 phytochemicals—eight diterpenoids and four biflavonoids—with SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity from the ethanol extracts of the leaves of T. nucifera. All isolated compounds were examined for their 3CLpro inhibitory activities by enzymatic inhibition assay. Of the isolated compounds, biflavonoid amentoflavone (9) was identified as a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV 3CLpro, exhibiting an IC50 value of 8.3 μM. We also report on enzyme-inhibition mechanisms ascertained using kinetic plots and molecular docking experiments.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Isolation and identification of SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory compounds

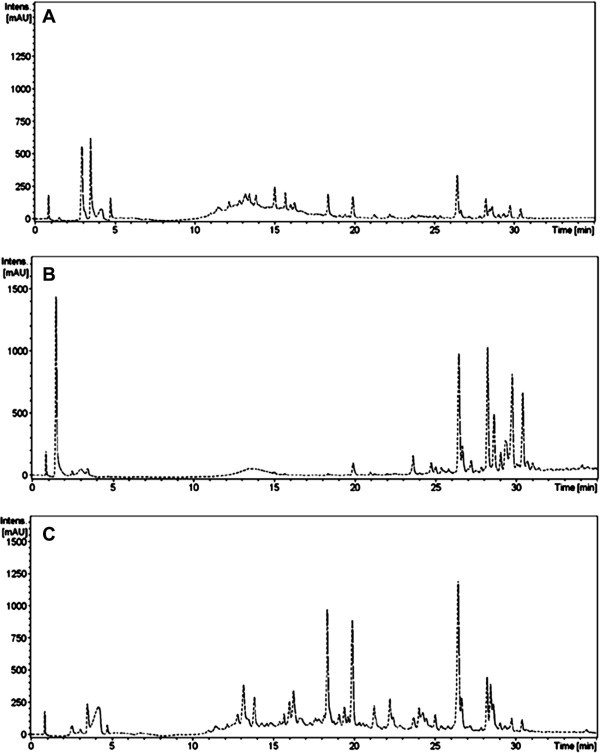

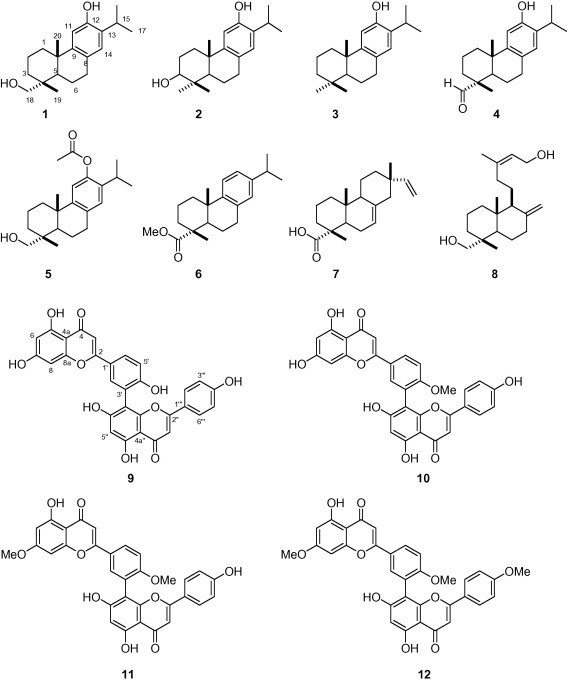

The crude ethanol extracts of the leaves of T. nucifera were directly analyzed by HPLC chromatography. As shown in Figure 1 , more than 15 principal secondary metabolite peaks were detected in the chromatogram by photodiode array (PDA) at 210 nm. As a first step toward relating biological activity to principle metabolites, we assessed the SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory effects of the T. nucifera EtOH extract, along with n-hexane and EtOAc fractions. The results indicate that n-hexane (27% at 50 μg/mL, Fig. 1B) and EtOAc fractions (53% at 50 μg/mL, Fig. 1C) have good 3CLpro inhibitory activity. We then used repeated open silica gel column, RP-18 gel, and Sephadex (LH-20) chromatography to isolate bioactive compounds from both fractions for further phytochemical investigation. Their chemical structures were unambiguously assigned on the basis of a comprehensive spectral analysis of mass spectrometry and 1D, 2D NMR data, and a comparison to previously published data.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Compounds isolated from the n-hexane fraction (1–8) were identified as the known diterpenoid species 18-hydroxyferruginol (1), hinokiol (2), ferruginol (3), 18-oxoferruginol (4), O-acetyl-18-hydroxyferruginol (5), methyl dehydroabietate (6), isopimaric acid (7), and kayadiol (8). The EtOAc fraction yielded four biflavonids (9–12), which were identified as amentoflavone (9), bilobetin (10), ginkgetin (11), and sciadopitysin (12) (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 1.

(A) HPLC total chromatogram of EtOH extract of T. nucifera. HPLC chromatograms of hexane (B) and EtOAc fraction (C) of T. nucifera leaves extract.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of isolated compounds (1−12) from leaves of the T. nucifera.

2.2. Effects of isolated compounds on the activity of SARS-CoV 3CLpro

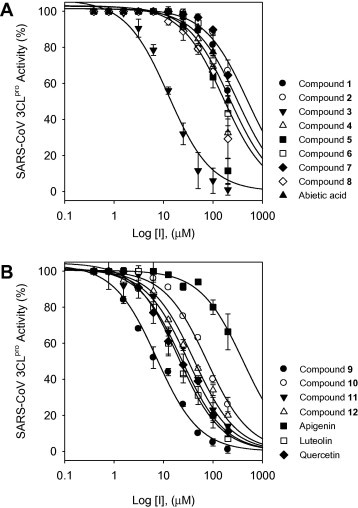

To investigate the relative inhibitory potency of the 12 compounds (1–12) against SARS-CoV 3CLpro, we measured SARS-CoV 3CLpro activity in the presence or absence of test compounds using fluorogenic methods. Unless otherwise stated, all compounds were first tested at a single maximum concentration of 300 μM, after which IC50 determinations were made using twofold serial dilutions stating from 300 μM, following a previously described protocol. The 12 tested phytochemicals inhibited SARS-CoV 3CLpro in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 3 . The inhibitory effects of isolate compounds (1–12) on 3CLpro activity, in vitro are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 .

Figure 3.

Effects of diterpenoids (1–8, A) and biflavones (9–12, B) on the activity of SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

Table 1.

SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activities of isolated diterpenoids (1−8)

| Compound | Inhibitiona (%) | IC50b (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45.8 ± 5.0 | 220.8 ± 10.4 |

| 2 | 39.1 ± 11.6 | 233.4 ± 22.2 |

| 3 | 92.7 ± 3.7 | 49.6 ± 1.5 |

| 4 | 70.5 ± 1.3 | 163.2 ± 13.8 |

| 5 | 78.6 ± 8.8 | 128.9 ± 25.2 |

| 6 | 46.7 ± 7.2 | 207.0 ± 14.3 |

| 7 | 28.9 ± 2.2 | 283.5 ± 18.4 |

| 8 | 75.2 ± 5.4 | 137.7 ± 12.5 |

| Abietic acidc | 58.0 ± 4.8 | 189.1 ± 15.5 |

SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition rate for compounds concentration at 200 μM.

All compounds were examined in a set of duplicated experiment; IC50 values of compounds represent the concentration that caused 50% enzyme activity loss.

This compound was used as diterpenoid positive control.

Table 2.

SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activities of isolated biflavonoids (9−12) and commercial flavonoids

| Compound | IC50a (μM) | Inhibition type (Ki, μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 8.3 ± 1.2 | Noncompetitive (13.8 ± 1.5) |

| 10 | 72.3 ± 4.5 | Noncompetitive (80.4 ± 4.0) |

| 11 | 32.0 ± 1.7 | Noncompetitive (30.2 ± 2.6) |

| 12 | 38.4 ± 0.2 | Noncompetitive (35.6 ± 1.1) |

| Apigeninb | 280.8 ± 21.4 | NDc |

| Luteolinb | 20.0 ± 2.2 | ND |

| Quercetinb | 23.8 ± 1.9 | ND |

All compounds were examined in a set of triplicate experiment; IC50 values of compounds represent the concentration that caused 50% enzyme activity loss.

These compounds were used to SAR study and positive control for biflavonoids.

ND = not determined.

Table 1 displays the inhibitory activities of the eight in-house diterpenoid libraries against SARS-CoV 3CLpro. The inhibitory potencies and capacities were not affected by subtle changes in structure. A recent study by Shyur and co-workers12 showed that naturally occurring diterpenoid inhibit SARS-CoV 3CLpro activity at concentrations of less than 100 μM. In the present study, we found that these compounds also possessed similar inhibitory effects toward 3CLpro, with over half of the tested compounds (1, 2, and 4–8) inhibiting SARS-CoV 3CLpro at concentrations up to 100 μM. One exception was ferruginol (3), which exhibited significantly greater inhibitory effects on 3CLpro (IC50 = 49.6 μM) in our laboratory assay system than was found in this previous study. Notably, ferruginol (3) was nearly a fourfold more potent inhibitor than the parent abietan diterpenoid, abietic acid (IC50 = 189.1 μM).

In separate experiments, we assessed the biflavonoid derivatives (9–12) for inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro. As shown in Table 2, we found that the IC50 values of the biflavonoid derivatives 9–12 against SARS-CoV 3CLpro ranged from 8.3 to 72.3 μM. Of these compounds (9–12), amentoflavone (9) (IC50 = 8.3 μM) was the most potent SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitor. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the biological activity of biflavonoid derivatives toward SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

2.3. Structural–activity relationships (SARs) of biflavones 9–12

We next performed a qualitative analysis of the structural–activity relationships of compounds 9−12. A comparison of biflavone amentoflavone (9) with biflavone derivatives revealed that methylation of 7-, 4′-, and 4′′′-hydroxyl groups diminished inhibitory activity, whereas a naked biflavone, as in amentoflavone (9), increased inhibitory activity. Thus, compounds 10–12, which have methoxy groups, were less potent (IC50 = 32.0–72.3 μM) than compound 9, which lacks a methoxy group. We also found that the location of the methoxy group within these compounds was positively correlated with the potency of the compounds against SARS-CoV 3CLpro. The terminal methoxy groups in C-4′ and -4′′′ were not required for 3CLpro inhibition, as shown by compounds 10 and 12, which exhibited moderated potency against 3CLpro. However, substitution of a methoxy group at C-7 appeared to enhance the potency of the compound. For example, the C-7 methoxy group of compounds 11 (IC50 = 32.0 μM) and 12 (IC50 = 38.4 μM) might be responsible for twofold increase in the SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity relative to compound 10 (IC50 = 72.3 μM). The rank order of potency of these derivatives was compound 9 (8.3 μM) > compound 11 (32.0 μM) > compound 12 (38.4 μM) > compound 10 (72.3 μM).

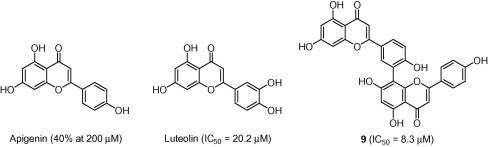

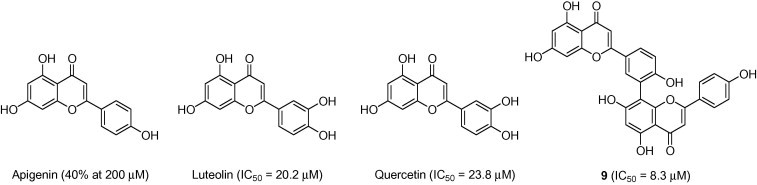

To investigate the 3CLpro-inhibitory profile of biflavones in detail and to elucidate their structure–activity relationships, we accessed a series of authentic flavones (apigenin, luteolin and quercetin) (Fig. 4 ). The most potent inhibitor (9) exhibited an IC50 value toward SARS-CoV 3CLpro of 8.3 μM, making this compound about 30-fold more potent than the parent compound apigenin, which had a threshold value of 40% at 200 μM in this experiment (Table 2). Moreover, this activity was higher than that of another flavone, luteolin (IC50 = 20.2 μM). In the case of flavones, flavones with a C-3′-substituted hydroxyl group, as in luteolin, were more potent inhibitors than apigenin. Thus, these data suggested that substitution of the apigenin motif within the flavone as in biflavonoid (9) may play a pivotal role in SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition. This relationship was also supported by quercetin (IC50 = 23.8 μM), which has a hydroxyl group at the C-3′ position in the flavones (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of apigenin, luteolin, quercetin, and amentoflavone (9).

2.4. Mechanistic analysis and molecular docking experiment

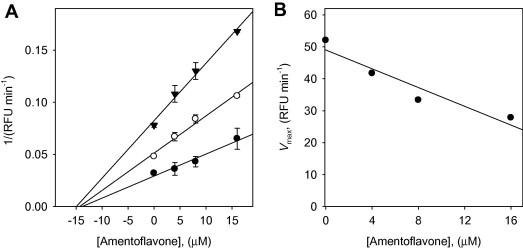

We also characterized the inhibitory mechanism of the isolated biflavonoids against SARS-CoV 3CLpro activity. A representative example is illustrated in Figure 5 , which shows the inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro by the most effective compound, amentoflavone (9). The enzyme inhibition mechanisms of biflavonoids were modeled using double-reciprocal plots (Lineweaver-Burk and Dixon plots). As shown in Figure 5A, the Dixon plot of [I] versus 1/V (RFU/min−1) results in a family of straight lines with the same x-axis intercept, as illustrated for the three fluorogenic substrate concentrations [S], 1/2[S], and 1/4[S], respectively. This indicates that biflavonoids (9–12) exhibit noncompetitive inhibition characteristics toward 3CLpro because V max decreased without a change in K m value in the presence of increasing concentrations of inhibitors (Fig. 5B). The K i values of these biflavonoids were easily calculated from Dixon plot with a common intercept on the x-axis (corresponding to −K i).

Figure 5.

(A) Dixon plot for inhibition of amentoflavone (9) on 3CLpro for the proteolysis of substrate. In the presence of difference concentrations of substrate: 2.5 μM (▾), 5.0 μM (○), and 10.0 μM (●). (B) The plot of Vmax versus inhibitor concentrations for determining the inhibition type.

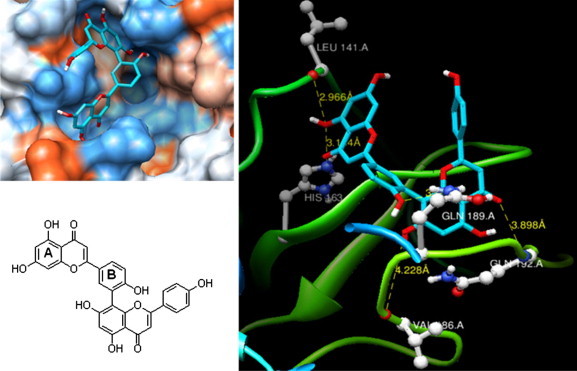

To further elucidate the interaction of SARS-CoV 3CLpro with biflavone 9, we employed in silico docking simulation. The three-dimensional structure of SARS-CoV 3CLpro in complex with a substrate-analogue inhibitor (coded 2z3e)24 obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/) was used for modeling analysis. Computer docking analysis revealed that biflavone 9 nicely fits in the binding pocket of 3CLpro. As shown in Figure 6 , the C5 hydroxyl group of 9 formed two hydrogen bonds with the nitrogen atom of the imidazole group of His163 (3.154 Å) and OH of Leu141 (2.966 Å) which are belonging to S1 site of 3CLpro. Additionally, the hydroxyl group in the B ring of 9 forms hydrogen bonds with Gln189 (3.033 Å) which is belonging to S2 site of 3CLpro. Our studies of structure–activity relationships implicated interactions with Val186 (4.228 Å) and Gln192 (3.898 Å) as one of the key chemotypes in this inhibitor. Moreover, the potencies of the inhibitors amentoflavone (9) and apigenin correlated well with their binding energies: amentoflavone (9) = −11.42 kcal/mol; apigenin = −7.79 kcal/mol. These differences in binding energy apparently manifest as a 30-fold smaller IC50 value of amentofalvone (9) toward 3CLpro compared with apigenin. Thus, this docking experiment supports the inferences drawn from the enzymatic assay, revealing an important inhibitory action of biflavones on SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

Figure 6.

The binding pose of amentoflavone (9) in SARS-CoV 3CLpro. Ribbon plot of 9 complexed to 3CLpro with hydrogen bonding.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, our results confirm that amentoflavone (9), isolated from T. nucifera, is an effective inhibitor of SARS-CoV 3CLpro and is more effective than the corresponding flavones (apigenin and luteolin) and biflavonoid derivatives containing various numbers of methoxy groups. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to describe the inhibitory effects of amentoflavone (9) against 3CLpro. The IC50 value of this inhibitor, although higher than those of peptide-derived 3CLpro inhibitors, is nonetheless in the low micromolar range. Thus, we believe that this compound may be a good candidate for development as a natural therapeutic drug against SARS-CoV infection.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. General apparatus and chemicals

1H and 13C NMR along with 2D NMR data were obtained on JNM-ECA 400, 500 and 600 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) spectrometer using CDCl3, DMSO-d 6, acetone-d 6, and methanol-d 3 with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Melting points were measured on a Thomas Scientific Capillary Melting Point Apparatus (Electronthermal 9300, UK), and are uncorrected. Optical rotation values were measured using a Perkin-Elmer 343 polarimeter and [α]D-values are given in units of 10−1 deg cm2 g−1. Chromatographic separations employed thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Merck, Darmastdt, Germany) using commercially available glass plate pre-coated with silica gel; products were visualized under UV light at 254 and 366 nm. Column chromatography was carried out using 230–400 mesh silica gel (Kieselgel 60, Merck, Germany). RP-18 (ODS-A, 12 nm, S-150 mM; YMC), and Sephadex LH-20 (Amersham Biosciences).

4.2. Plant material

The leaves of Torreya nucifera were collected at Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, in October 2003. A voucher specimen was deposited in the author’s laboratory in the KRIBB (Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology).

4.3. Extraction and isolation

Dried leaves (1.8 kg) of T. nucifera were extracted three times (2.0 L each) with ethanol (EtOH) at room temperature for 4 days. The ethanol extracts (228 g) were suspended in H2O, and the resulting aqueous layer was successively partitioned with n-hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and H2O to yield a hexane fraction (98 g), an EtOAc fraction (69 g), and aqueous fraction (44 g). The hexane-soluble fraction was subjected to silica gel column chromatography, with elution using a stepwise gradient mixture of n-hexane/EtOAc (100:0→10:1), to yield eight fractions (HF1-8). Fraction HF4 (10.6 g) was loaded onto a silica gel column, and eluted with a mixture of n-hexane/EtOAc (80:0→10:1) as the mobile phase to yield six fractions (HF4A-4F). Fraction HF4B (1.2 g) was further fractionated using a silica gel column; elution with a mixture of n-hexane/EtOAc (80:0→10:1) yielded compounds 3 (40 mg) and 4 (70 mg). Fraction HF4C (2.0 g) was chromatographed on a column of RP C-18 (75C18-PREP), and eluted with 70% acetonitrile–H2O, to yield compounds 1 (11 mg), 2 (20 mg), 6 (12 mg), 7 (34 mg), and 8 (43 mg). Fraction HF4C was further purified by silica gel chromatography and eluted with n-hexane/CH2Cl2 (80:20, v/v) to yield compound 5 (17 mg).

The EtOAc fraction of T. nucifera was subjected to column chromatography over a silica gel; eluting with a chloroform-to-acetone gradient yielded nine fractions (EF1-9). Fraction EF2 (8.8 g) was chromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column and eluted with methanol to yield five sub-fractions (EF2A-2E). Sub-fraction EF2A (1.4 g) was purified by silica gel chromatography and eluted with n-hexane/EtOAc (60:0→1:1) to yield compound 12 (30 mg). Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography was used to isolate compound 9 (50 mg) from fraction EF2C (0.9 g) using identical solvent conditions. This sub-fraction was subsequently separated through chromatography on a preparative-HPLC to yield compounds 10 (12 mg) and 11 (18 mg).

4.3.1. 18-Hydroxyferruginol (1)

Colorless prisms; = +109.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); mp: 175−180 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3H, s, H-19), 1.18 (3H, s, H-20), 1.21 (3H, d, H-16), 1.22 (3H, d, H-17), 1.36 (1H, m, H-1α), 1.42 (1H, m, H-3), 1.59 (1H, m, H-5), 1.64 (1H, m, H-6), 1.71 (1H, m, H-2), 2.16 (1H, m, H-1β), 2.80 (2H, m, H-7), 3.09 (1H, m, H-15), 3.21 (1H, d, J = 10.9 Hz, H-18α), 3.45 (1H, d, J = 11.0 Hz, H-18β), 6.61 (1H, s, H-11), 6.81 (1H, s, H-14); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.6 (C-19, t), 18.8 (C-6, t), 19.2 (C-2, t), 22.7 (C-16, q), 22.9 (C-17, q), 25.4 (C-20, q), 27.0 (C-15, d), 29.6 (C-7, t), 35.2 (C-3, t), 37.5 (C-10, s), 38.0 (C-4, s), 38.6 (C-1, t), 44.0 (C-5, d), 72.4 (C-18, t), 111.1 (C-11, d), 126.8 (C-14, d), 127.3 (C-8, s), 131.7 (C-13, s), 148.5 (C-9, s), 150.9 (C-12, s).

4.3.2. Hinokiol (2)

Colorless crystal; = +8.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); mp: 218−222 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3H, s, H-18), 1.04 (3H, s, H-19), 1.15 (3H, s, H-20), 1.20 (3H, d, H-16), 1.22 (3H, d, H-17), 1.28 (1H, dd, J = 11.7, 2.1 Hz, H-15), 1.51 (1H, ddd, J = 26.8, 13.1, 4.1 Hz, H-1α), 1.72 (1H, m, H-2α), 1.74 (1H, m, H-6α), 1.77 (1H, m, H-2β), 1.84 (1H, m, H-6β), 2.17 (1H, m, H-1β), 2.75 (1H, m, H-7α), 2.86 (1H, dd, J = 16.5, 5.5 Hz, H-7β), 3.08 (1H, m, H-15), 3.27 (1H, dd, J = 11.6, 4.8 Hz, H-3), 6.59 (1H, s, H-11), 6.81 (1H, s, H-14); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 15.6 (C-18, q), 19.2 (C-6, t), 22.7 (C-16, q), 22.9 (C-17, q), 25.0 (C-20, q), 27.0 (C-15, d), 28.2 (C-20, q), 28.4 (C-2, t), 30.2 (C-7, t), 37.2 (C-1, t), 37.5 (C-10, s), 39.2 (C-4, s), 78.9 (C-3, d), 111.2 (C-11, d), 126.8 (C-14, d), 127.3 (C-8, s), 131.9 (C-13, s), 148.0 (C-9, s), 150.9 (C-12, s).

4.3.3. Ferruginol (3)

Colorless oil; = +1.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (3H, s, H-19), 0.91 (3H, s, H-18), 1.15 (3H, s, H-20), 1.80 (1H, m, H-3α), 1.21 (3H, d, H-16), 1.22 (3H, d, H-17), 1.29 (1H, dd, J = 12.4, 2.1 Hz, H-5), 1.36 (1H, m, H-1α), 1.42 (1H, m, H-3β), 1.56 (1H, m, H-2α), 1.64 (1H, m, H-6α), 1.71 (1H, m, H-2β), 1.83 (1H, m, H-6β), 2.14 (1H, m, H-1β), 2.78 (2H, m, H-7), 3.09 (1H, seq, H-15), 6.61 (1H, s, H-11), 6.81 (1H, s, H-14); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 19.4 (C-2, t), 19.5 (C-6, t), 21.8 (C-19, q), 22.7 (C-16, q), 22.9 (C-17, q), 25.0 (C-20, q), 27.0 (C-15, d), 29.9 (C-7, t), 33.5 (C-18, q), 33.6 (C-10, s), 37.7 (C-4, s), 39.1 (C-1, t), 41.8 (C-3, t), 50.5 (C-5, d), 111.2 (C-11, d), 126.8 (C-14, d), 127.5 (C-8, s), 131.5 (C-13, s), 148.9 (C-9, s), 150.8 (C-12, s).

4.3.4. 18-Oxoferruginol (4)

Colorless prisms; = +0.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); mp: 120−125 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.13 (3H, s, H-19), 1.20 (3H, s, H-20), 1.22 (6H, d, H-16, 17), 1.27 (1H, m, H-1α), 1.31 (1H, m, H-2α), 1.44 (2H, m, H-3), 1.76 (2H, m, H-6), 1.78 (1H, m, H-2β), 1.88 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 12.4 Hz, H-5), 2.21 (1H, m, H-1β), 2.79 (2H, m, H-7), 3.10 (1H, m, H-15), 6.62 (1H, s, H-11), 6.82 (1H, s, H-14), 9.23 (COH); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 14.2 (C-19, q), 17.9 (C-2, t), 21.7 (C-6, t), 22.7 (C-16, q), 22.9 (C-17, q), 25.2 (C-20, q), 26.9 (C-15, d), 29.2 (C-7, t), 32.1 (C-3, t), 36.4 (C-10, s), 38.0 (C-1, t), 42.9 (C-5, d), 50.1 (C-4, s), 111.0 (C-11, d), 126.9 (C-14, d), 127.1 (C-8, s), 132.2 (C-13, s), 147.3 (C-9, s), 151.1 (C-12, s), 206.6 (C-18, s).

4.3.5. O-Acetyl-18-hydroxyferruginol (5)

White powder; = +11.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); mp: 155–160 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3H, s, H-19), 1.16 (3H, s, H-20), 1.18 (3H, d, H-17), 1.20 (3H, d, H-16), 1.31 (1H, dd, J = 3.4, 13.0 Hz, H-1β), 1.37 (2H, m, H-3), 1.58 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 12.3 Hz, H-5), 1.64 (2H, m, H-6), 1.73 (2H, m, H-2), 2.11 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz, H-1α), 2.15 (3H, s, H-22), 2.77 (2H, m, H-7), 3.11 (1H, m, H-15), 3.20 (1H, d, J = 11.0 Hz, H-18β), 3.45 (1H, d, J = 10.9 Hz, H-18α), 6.61 (1H, s, H-11), 6.79 (1H, s, H-14); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.5 (C-19, q), 18.8 (C-2, t), 19.1 (C-6, q), 22.7 (C-16, q), 22.9 (C-17, q), 25.3 (C-20, q), 26.8 (C-15, d), 29.5 (C-7, t), 31.1 (C-22, q), 35.2 (C-3, t), 37.4 (C-4, s), 37.9 (C-10, s), 38.5 (C-1, t), 43.9 (C-5, d), 72.3 (C-18, t), 111.1 (C-11, d), 126.7 (C-14, d), 127.0 (C-13, s), 131.8 (C-8, s), 148.3 (C-9, s), 151.0 (C-12, s), 207.7 (C-21, s).

4.3.6. Methyl dehydroabietate (6)

Colorless oil; = −0.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.18 (3H, s, H-20), 1.19 (6H, d, H-16, 17), 1.20 (3H, s, H-19), 1.13−1.50 (2H, m, H-6), 1.59−1.74 (2H, m, H-1), 1.66−1.83 (2H, m, H-2), 1.83−2.28 (2H, m, H-3), 2.22 (1H, dd, J = 2.8, 13.1 Hz, H-5), 2.80 (1H, m, H-15), 2.86 (2H, m, H-2), 3.64 (3H, s, H-18OMe), 6.86 (1H, s, H-14), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz, H-12), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 1.2 Hz, H-11); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 16.7 (C-19, q), 18.7 (C-2, t), 21.9 (C-6, t), 24.2 (C-16, -17, q), 25.3 (C-20, q), 30.2 (C-7, t), 33.6 (C-15, d), 36.8 (C-3, t), 37.1 (C-10, s), 38.1 (C-1, t), 45.0 (C-5, d), 47.8 (C-4, s), 52.1 (C-18OMe, s), 124.1 (C-11, d), 124.3 (C-12, d), 127.0 (C-14, d), 134.9 (C-8, s), 145.9 (C-13, s), 147.1 (C-9, s), 179.3 (C-18, s).

4.3.7. Isopimaric acid (7)

Colorless prisms; = −0.9 (c 0.1, CHCl3); mp: 150−160 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3H, s, H-19), 0.88 (3H, s, H-20), 1.12 (1H, m), 1.24 (3H, s, H-17), 1.36 (2H, m), 1.54 (3H, m), 1.63−2.00 (9H, m), 4.84 (1H, dd like, J = 12.9 Hz, H-16β), 4.91 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 21.2 Hz, H-16α), 5.30 (1H, d like, H-17), 5.78 (1H, dd, J = 12.8, 21.2 Hz, H-15); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 15.5 (C-20, q), 17.3 (C-19, q), 18.1 (C-2, t), 20.2 (C-11, t), 21.7 (C-17, q), 25.4 (C-6, t), 35.2 (C-10, s), 36.3 (C-12, t), 37.0 (C-3, t), 37.2 (C-13, s), 39.0 (C-1, t), 45.2 (C-5, d), 46.3 (C-4, s), 46.5 (C-14, t), 52.2 (C-9, d), 109.5 (C-16, t), 121.2 (C-7, d), 135.9 (C-8, s), 150.5 (C-15, d), 185.3 (C-18, s).

4.3.8. Kayadiol (8)

Colorless prisms; = +43.8 (c 1.4, CHCl3); mp: 112 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.69 (3H, s, H-20), 0.72 (3H, s, H-19), 1.64 (3H, s, H-16), 0.98−1.80 (15H, m), 1.97−2.12 (2H, m), 2.35 (1H, m, H-9), 3.07 (1H, d, J = 10.3 Hz, H-18α), 3.40 (1H, d, J = 10.9 Hz, H-18β), 4.13 (2H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H-15), 4.49 (1H, s, H-17β), 4.81 (1H, s, H-17α), 5.35 (1H, t, J = 6.1 Hz, H-14); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 15.5 (C-20, q), 16.5 (C-16, q), 17.8 (C-2, t), 18.8 (C-11, t), 21.9 (C-6, t), 24.3 (C-19, q), 35.6 (C-3, t), 38.1 (C-1, t), 38.2 (C-12, t), 38.5 (C-10, s), 38.7 (C-7, t), 39.7 (C-4, s), 48.6 (C-5, d), 56.4 (C-9, d), 59.6 (C-15, t), 72.2 (C-18, t), 106.6 (C-17, t), 123.2 (C-14, d), 140.7 (C-13, s), 148.5 (C-8, s).

4.3.9. Amentoflavone (9)

Pale yellow amorphous powder; mp: 230 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ 6.18 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-6), 6.37 (1H, s, H-6′′), 6.45 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-8), 6.70 (2H, s, H-3, 3′′), 6.80 (2H, s, H-3′′′, 5′′′), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, H-5′), 7.58 (2H, s, H-2′′′, 6′′′), 8.00 (1H, dd, J = 2.3, 8.6 Hz, H-6′), 8.02 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-2′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ 94.0 (C-6′′, d), 98.8 (C-6, 8, d), 102.6 (C-3′′, d), 102.9 (C-4a, s), 103.5 (C-3, d), 103.7 (C-8′′, s), 104.2 (C-4a′′, s), 115.7 (C-3′′′, 5′′′, d), 116.4 (C-5′, d), 120.3 (C-1′′′, s), 120.7 (C-1′, s), 121.4 (C-3′, s), 127.7 (C-6′, d), 128.2 (C-2′′′, 6′′′, d), 131.4 (C-2′, d), 154.5 (C-8a′′, s), 157.4 (C-8a, s), 160.0 (C-5′′, s), 160.5 (C-5, s), 160.9 (C-4′, s), 161.4 (C-7′′, s), 162.7 (C-4′′′, s), 163.6 (C-2, s), 163.8 (C-2′′, s), 164.1 (C-7, s), 181.7 (C-4′′, s), 182.1 (C-4, s).

4.3.10. Bilobetin (10)

Pale yellow amorphous powder; mp: 225 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ 3.78 (OMe), 6.18 (1H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-6), 6.37 (1H, s, H-6′′), 6.47 (1H, s, H-8), 6.71 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-3′′′, 5′′′), 6.78 (1H, s, H-3′′), 6.91 (1H, s, H-3), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-5′), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-2′′′, 6′′′), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-2′), 8.16 (1H, m, H-6′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ 55.8 (OMe), 94.1 (C-8, d), 98.7 (C-6, d), 98.9 (C-6′′, d), 102.4 (C-3, 3′′, d), 103.4 (C-4a′′, s), 103.6 (C-8′′, 4a, s), 111.6 (C-5′, d), 115.7 (C-3′′′, 5′′′, d), 121.2 (C-1′′′, s), 121.6 (C-3′, s), 122.4 (C-1′, s), 127.9 (C-2′, d), 128.1 (C-2′′′, 6′′′, d), 130.9 (C-6′, d), 154.3 (C-8a′′, s), 157.4 (C-8a, s), 160.4 (C-5′′, s), 160.6 (C-4′, s), 161.1 (C-4′′′, s), 161.4 (C-5, s), 162.6 (C-7′′, s), 163.1 (C-2, s), 163.3 (C-7, s), 164.3 (C-2′′, s), 181.7 (C-4′′, s), 182.0 (C-4, s).

4.3.11. Ginkgetin (11)

Pale yellow amorphous powder; mp: 235 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d 6) δ 5.74 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz, H-6), 5.96 (1H, s, H-6′′), 6.03 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz, H-8), 6.46 (2H, H-3′′′, 5′′′), 6.47 (1H, s, H-3′′), 6.48 (1H, s, H-3), 6.89 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-5′), 7.16 (2H, H-2′′′, 6′′′), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H-2′), 7.73 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 9.2 Hz, H-6′); 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d 6) δ 55.9 (OMe), 56.4 (OMe), 94.9 (C-8, d), 99.7 (C-6, d), 99.8 (C-6′′, d), 104.2 (C-3, 3′′, d), 104.4 (C-4a′′, s), 104.8 (C-8′′, s), 105.5 (C-4a, s), 111.5 (C-5′, d), 115.4 (C-3′′′, 5′′′, d), 116.8 (C-1′′′, s), 117.5 (C-3′, s), 122.8 (C-1′, s), 124.3 (C-2′, d), 128.8 (C-2′′′, 6′′′, d), 132.2 (C-6′, d), 154.3 (C-8a′′, s), 158.9 (C-8a, s), 160.4 (C-5′′, s), 162.0 (C-7′′, s), 162.1 (C-4′, s), 162.3 (C-4′′′, s), 163.0 (C-5, s), 163.5 (C-2, s), 163.6 (C-2′′, s), 165.0 (C-7, s), 183.1 (C-4′′, s), 183.4 (C-4, s).

4.3.12. Sciadopitysin (12)

Pale yellow amorphous powder; mp: 273 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d 3) δ 6.18 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz, H-6), 6.46 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz, H-8), 6.66 (1H, s, H-6′′), 6.90 (2H, H-3, 3′′), 6.93 (2H, H-3′′′, 5′′′), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-5′), 7.61 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2′′′, 6′′′), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-2′), 8.17 (1H, dd, J = 2.6, 8.5 Hz, H-6′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d 3) δ 55.5 (OMe), 55.9 (OMe), 56.5 (OMe), 94.1 (C-8, d), 95.5 (C-6, d), 98.9 (C-6′′, d), 103.2 (C-3′′, d), 103.7 (C-4a′′, s), 103.8 (C-3, d), 104.1 (C-8′′, s), 104.6 (C-4a, s), 111.8 (C-5′, d), 114.5 (C-3′′′, 5′′′, d), 121.2 (C-3′, s), 122.6 (C-1′, s), 122.7 (C-1′′′, s), 127.9 (C-2′′′, 6′′′, d), 128.3 (C-2′, d), 153.4 (C-6′, d), 157.4 (C-8a′′, s), 160.3 (C-8a, 5′′, s), 161.4 (C-4′, s), 161.5 (C-5, s), 162.3 (C-4′′′, s), 162.6 (C-7′′, s), 163.1 (C-2, s), 163.4 (C-2′′, s), 164.3 (C-7, s), 181.7 (C-4′′, s), 182.3 (C-4, s).

4.4. SARS 3C-like protease (3CLpro) inhibition assay

The inhibitory effect of ethanol extract compounds on SARS-CoV 3CLpro (Lifesensors Co., USA) was measured using a FRET method developed by us as described previously.14 In this assay, the fluorogenic peptide Dabcyl-KNSTLQSGLRKE-Edans (Anygen Co., Republic of Korea) is used as a substrate, and the enhanced fluorescence due to substrate cleavage is measured at 360/40 nm and recorded as relative fluorescence units (RFUs). The IC50 value of individual compounds was measured in a reaction mixture containing 10 μg/mL of the 3CLpro (final concentration, 2.5 μg) and 10 μM fluorogenic 14-mer peptide substrate in 20 mM Bis-Tris buffer. Reactions were run for 60 min at room temperature with continuous monitoring of fluorescence with a FLx 800 (BioTeck Instrument Inc., USA). The inhibition ratio was calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

where C is the fluorescence of the control (enzyme, buffer, and substrate) after 60 min of incubation, C 0 is the fluorescence of the control at zero time, S is the fluorescence of the tested samples (enzyme, sample solution, and substrate) after incubation, and S 0 is the fluorescence of the tested samples at zero time. To allow for the quenching effect of the samples, the sample solution was added to the reaction mixture C, and any reductions in fluorescence were assessed. Kinetic parameters were obtained using various concentrations of FRET peptide in the fluorescent assay. The maximal velocity (V max = 44.4 ± 6.2 intensity min−1), Michaelis-Menten constant (K m = 9.7 ± 0.2 μM), and inhibition constant (K i) were calculated from the Lineweaver-Burk and Dixon plots.

4.5. Molecular docking study of SARS-CoV 3CLpro with selected inhibitors

Molecular docking with SARS-CoV 3CLpro was simulated and analyzed using Autodock 3.0.5 software.25 The SARS-CoV 3CLpro Crystal structure {PDB code 2Z3E with inhibitor KCQ, (3S)-3-[(2s)-2-amino-3-oxyobutyl]pyrrolidin-2-one} at 2.3 Å was prepared for docking and post-docking refinement.25 For docking experiment of each biflavone with 2Z3E, all water molecules and the inhibitor (KCQ) located in the active site of 2Z3E were removed, and the structure information containing only the amino acid residues of the 3CLpro enzyme was used. AutoDockTools software was used for the addition of polar hydrogen atoms to the macromolecule to correct calculation of partial atomic charges. Aspartic and glutamic acids were deprotonated, lysine and arginine were protonated, and histidine was neutral. Kollman charges were assigned for all atoms. Three dimensional affinity grid size with 60 × 60 × 60 on active size with 0.375 Å spacing was calculated for each atom type by using of AutoGrid 3. The docking parameters for Lamarckian genetic algorithm between 3CLpro with different biflavones were as follows: population size of 250 individuals, random starting position and conformation, translation step ranges of 2.0 Å, maximum of 10,000,000 energy evaluations, number of top individuals to survive to next generation 1, maximum of generations 27,000, mutation rate of 0.02, rate of crossover 0.8, local search rate 0.06, 50 docking runs. The maximum number of iteration per local search was set to 300. Each docking job produced 50 docked conformations. Binding energy between the three-dimensional structure of SARS-CoV 3CLpro and biflavones was then calculated. The docking results were ranked according to docking energy scores.

4.6. HPLC apparatus and chromatographic conditions

The extracts (5 mg/mL) and fractions (5 mg/mL) were passed through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore, MSI, Westboro, MA, USA) before chromatographic separation using an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a quaternary HPLC pump, degasser, autosampler and UV detector (VWD). The mobile phase for HPLC consisted of water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The solvent gradient was as follows (starting with 100% solvent A): 0 min, 0% B; 10 min, 30% B; 20 min, 60% B; 30 min, 100% B; 35 min, 100% B. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, the injection volume was 10 μL and eluent was detected at 210 nm. All HPLC analyses were performed at 30 °C.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Research Foundation grant funded by Korea government (MEST) (No. 2010-0002047) and KRIBB Research Initiative Program, Republic of Korea. Molecular docking study was partly supported by the EU Framework Program (EU-FP) (Grant No. 2009-50283).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.035.

Supplementary data

HPLC chromatograms, Spectra of bisflavonoids (NMR and LC/Ms data), Spectra of diterpenoids (NMR and LC/MS data) and Molecular docking study of biflavones (9–12).

References and notes

- 1.Berger A., Drosten C., Doerr H.W., Sturmer M., Preiser W. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;29:13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stadler K., Masignani V., Eickmann M., Becker S., Abrignani S., Klenk H.D., Rappuoli R. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:209. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., Berger A., Burguiere A.M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N., Grywna K., Kramme S., Manuguerra J.C., Muller S., Rickerts V., Sturmer M., Vieth S., Klenk H.D., Osterhaus A.D., Schmitz H., Doerr H.W. N. Eng. J. Med. 2003;348:1967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Lancet. 2003;361:1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.-H., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., De Risi J.L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D.D., Peret T.C.T., Burns C., Ksiazek T.G., Rollin P.E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen-Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Gunther S., Osterhaus A.D.H.E., Drosten C., Pallansch M.A., Anderson L.J., Bellini W.J. Science. 2003;300:1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwang P., Mesturs J.R., Hilgenfield R. Science. 2003;300:1763. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cinatl J., Jr., Michaelis M., Hoever G., Preiser W., Doerr H.W. Antiviral Res. 2005;66:81. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C.-Y., Jan J.-T., Ma H.-H., Kuo C.-J., Juan H.-F., Cheng Y.-S.E., Hsu H.-H., Huang H.-C., Wu D., Brik A., Liang F.-S., Liu R.-S., Fang J.-M., Chen S.-T., Liang P.-H., Wong C.-H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao R.Y., Tsui W.H.W., Lee T.S.W., Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Huang J.-D., Hu L., Chen G., Chen Z., Zhang L., He T., Chan K.-H., Tse H., To A.P.C., Ng L.W.Y., Wong B.C.W., Tsoi H.-W., Yang D., Ho D.D., Yuen K.-Y. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1293. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L.-R., Wang Y.-C., Lin Y.-W., Chou S.-Y., Chen S.-F., Liu L.-T., Wu Y.-T., Kuo C.-J., Chen T.S.-S., Juang S.-H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:3058. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shie J.-J., Fang J.-M., Kuo T.-H., Kuo C.-J., Liang P.-H., Huang H.-J., Yang W.-B., Lin C.-H., Chen J.-L., Wu Y.-T., Wong C.-H. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4469. doi: 10.1021/jm050184y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen C.-C., Kuo Y.-H., Jan J.-T., Liang P.-H., Wang S.-Y., Liu H.-G., Lee C.-K., Chang S.-T., Kuo C.-J., Lee S.-S., Hou C.-C., Hsiao P.-W., Chien S.-C., Shyur L.-F., Yang N.-S. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4087. doi: 10.1021/jm070295s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin C.-W., Tsai F.-J., Tsai C.-H., Lai C.-C., Wan L., Ho T.-Y., Hsieh C.-C., Chao P.-D.L. Antiviral Res. 2005;68:36. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryu Y.B., Park S.-J., Kim Y.M., Lee J.-Y., Seo W.D., Chang J.S., Park K.H., Rho M.-C., Lee W.S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1873. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison L.J., Asakawa Y. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:1211. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J.-W., Orihara Y. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1265. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S.-Y., Wu J.-H., Shyur L.-F., Kuo Y.-H., Chang S.-T. Holzforschung. 2002;56:487. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son K.-H., Oh H.-M., Choi S.-K., Han D.C., Kwon B.-M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:2019. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto T., Imai S., Ondo K., Takeyama N., Kataoka H., Yamamoto Y., Fukui K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1982;55:891. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antkowiak W., Apsimon J.W., Edwards O.E. J. Org. Chem. 1962;27:1930. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miura H., Kihara T., Kawano N. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1969;17:150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S.-H., Zhang H.-J., Niu X.-M., Yao P., Sun H.-D., Fong H.S.S. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:1002. doi: 10.1021/np030117b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanrahan J.R., Chebib M., Davucheron N.L.M., Hall B.J., Johnston G.A.R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:2281. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin J., Niu C., Cherney M.M., Zhang J., Huitema C., Eltis L.D., Vederas J.C., James M.N. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasam V.Z.M., Maass A., Schwichtenberg H., Wolf A., Jacq N., Breton V., Hofmann-Apitius M. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:1818. doi: 10.1021/ci600451t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HPLC chromatograms, Spectra of bisflavonoids (NMR and LC/Ms data), Spectra of diterpenoids (NMR and LC/MS data) and Molecular docking study of biflavones (9–12).