Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; DIEA, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; DIC, N,N-diisopropylcarbodiimide; Fmoc, 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl; HBTU, 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TIS, triisopropylsilane

Keywords: Glycoprobes, Surface-based interaction studies, Aminooxy-peptide, Coupling reagent

Abstract

An improved procedure for solid phase coupling of Boc-aminooxyacetic acid to peptides is described. By avoiding base-containing activation mixtures which cause over-acylation, it practically suppresses this unwanted side reaction and leads to near quantitative yields of Aoa-peptides, useful as glycoprobe precursors in glycomic studies.

With the ever-increasing awareness of the importance of protein glycosylation as a key player in inter- and intracellular communication,1, 2, 3, 4 the need for powerful chemical tools to document sugar–protein cross-talk is rising. One reason for such interest in carbohydrate–protein interactions is their implication in the targeting of enveloped viruses such as HIV, influenza-, and coronavirus,5, 6 an understanding of which will facilitate the design of carbohydrate-binding agents capable of neutralizing viral fusion and transmission. Different biophysical techniques have been used to monitor sugar–protein interactions,7, 8 including NMR, X-ray crystallography, and more recently, surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The latter is fast gaining recognition because of its sensitivity, low sample consumption, and capability for real-time monitoring. In this technique, one of the two interacting entities (protein or sugar) is immobilized onto the surface of a sensor chip, the other one is flown across and the resulting read-out enables both quantitation and kinetic analysis of the interaction

Among the two immobilization approaches possible, the sugar-on-chip option has demonstrable advantages9, 10 but requires a sugar in highly purified form and attached to the chip surface in a chemically well-defined manner. While the synthesis of complex carbohydrate structures is a fast expanding field,11, 12, 13, 14, 15 the structural diversity encountered in nature cannot yet be fully met in the laboratory. Thus, some glycans (e.g., bacterial polysaccharide repeating units, elongated mucin-type glycans or complex N-glycans) cannot be efficiently produced for lack of suitable synthetic chemistries or glycosyltransferases/glycosidases,16 and must be purified from natural sources. As the amount of material available is scarce, the immobilization chemistry to the sensor chip surface must be optimal to avoid losses of precious material. Although a direct aldehyde coupling has been described,17 its efficiency is questionable.

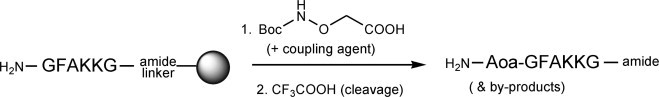

Recently, we reported a practically universal approach to carbohydrate immobilization on carboxymethyl dextran chips via standard peptide-bond chemistry, subsequent to chemical ligation of the sugar to a tailor-made peptide module.18 A chemospecific oxime linkage between the reducing end of the first monosaccharide and the peptide is achieved (Scheme 1 ) through the introduction of an N-terminal aminooxyacetic acid (Aoa) residue in the latter.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of oxime ligation between an N-terminal Aoa-containing peptide and a carbohydrate ligand. See Ref. 18 for further details.

Over the last decade, oxime chemistry has been proven as one of the most successful approaches to peptide chemical ligation.19, 20 Moreover, applications to sugar–peptide conjugation have also been described.21, 22 Despite the obvious advantages of this chemistry,23 it has as a main drawback that over-acylation of the NH–O nitrogen leads to undesired heterogeneity.24 To resolve this problem, deprotection of Aoa25 or use of N-trityl protection26 has been advocated; however, neither of these two approaches utilizes commercially available reagents.

In this work, we have explored the feasibility of minimizing Aoa over-acylation using Boc-protected Aoa and conventional coupling chemistry. Our study is based on two starting peptide substrates, the hexapeptide GFAKKG-amide18 (A) and a version N-terminally elongated with an ε-amino hexanoic acid (Ahx) spacer, Ahx-GFAKKG-amide27 (B), both acylated with Boc-Aoa-OH28 under different conditions (Fig. 1 , Table 1 ).

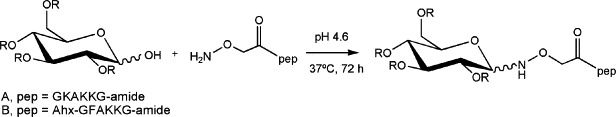

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of different conditions for Aoa-GFAKKG-amide [entries A(i–iii)] and Aoa-Ahx-GFAKKG-amide [entries B(i–iii)] synthesis. (i) Boc-Aoa-OH/HBTU/DIEA (3:3:6 equiv), 40 min; (ii) Boc-Aoa-OH/DIC (10:10 equiv), 60 min; (iii) Boc-Aoa-OH/DIC (8:8 equiv), 10 min. Peak assignations: a: target Aoa-peptides; b: starting peptide; c: diacylated peptide; d: triacylated peptide; e: N-terminal guanidine byproduct (uronium capping); f: oligomeric impurities. HPLC conditions: Phenomenex Luna C8 column; elution with linear 0–30% [panels A(1–iii)] and 0–40% [panels B(1–iii)] gradient of acetonitrile (+0.036% TFA) into water (+0.045% TFA) over 15 min; flow rate: 1 mL/min.

Table 1.

Acylation of substrates A and B with Boc-Aoa-OH using different coupling conditions

| Substrate | Entry | Boc-Aoa-OH (equiv) | Coupling agent (equiv) | DIEA (equiv) | Time (min) | Product distribution |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | ||||||

| A | i | 3 + 1.5 | HBTU (3 + 1.5) | 6 | 40 | 45 | 4 | 22 | 13 | 9 | 7 |

| A | ii | 10 | DIC (10) | — | 60 | 93 | 2 | 5 | — | — | — |

| A | iii | 8 | DIC (8) | — | 10 | 97 | 0 | 3 | — | — | — |

| B | i | 3 + 1.5 | HBTU (3 + 1.5) | 6 | 40 | 63 | 17 | 7 | — | 8 | 5 |

| B | ii | 10 | DIC (10) | — | 60 | 80 | 16 | 4 | — | — | — |

| B | iii | 8 | DIC (8) | — | 10 | 94 | 5 | 1 | — | — | — |

% Estimated by integration of HPLC peaks at 220 nm.

In line with previous work,24 we reasoned that the presence of base at the coupling step would favor over-acylation. Indeed, as shown on panels A(i) and B(i), otherwise efficient HBTU-mediated coupling conditions in this particular case generated a rather complex product mixture which, after TFA cleavage/deprotection,29 was shown by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analysis to contain the target Aoa-peptide (peak a, Fig. 1) accompanied by the di- and tri-acylated byproducts (peaks c and d, Fig. 1), plus the product of N-terminal guanidine capping,30 plus other peaks assumed to be higher-order oligomers.

In contrast, couplings relying on carbodiimide (DIC) activation were considerably cleaner (Fig. 1, panels A(ii, iii) and B(ii, iii)). Thus, substantial improvements in the yield of target Aoa-peptides (45% to 93% and 63% to 80%) for A and B, respectively, panels A(ii) and B(ii)) were observed when 10 equivalent of both Boc-Aoa-OH and DIC was used for 60 min. Interestingly, a shorter reaction time and a slight reduction in the excess of acylating agent led to even better results, amounting to practically quantitative conversion of both substances into the Aoa-derivatives (Table 1).

In conclusion, carbodiimide-based Boc-Aoa coupling, in conjunction with short reaction times, appears to provide a straightforward, efficient way to the Aoa-functionalized peptides required to prepare well-defined, lectin-capturing glycoprobes, by subsequent chemoselective oxime ligation. Using the optimized procedure described above, the Aoa-peptide (in any of its A or B versions) does not require any HPLC purification (see Supplementary Information pages) before the oxime ligation reaction, thus considerably contributing to an efficient preparation of sugar-functionalized sensor surfaces.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (Grant BIO2005-07592-C02-02 to D.A. and predoctoral fellowship BES-2006-12879 to C.J.C.) and from Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR 00494).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.090.

Supplementary data

References and notes

- 1.Taniguchi N., Miyoshi E., Gu J., Honke K., Matsumoto A. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:561. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitoma J., Bao X., Petryanik B., Shaerli P., Gaughet J.M., Yu S.Y., Kawashima H., Saito H., Ohtsubo K., Marth J.D., Khoo K.H., Von Adrian U.H., Lowe J.B., Fukuda M. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:409. doi: 10.1038/ni1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scanlan C.N., Offer J., Zitzmann N., Dwek R.A. Nature. 2007;446:1038. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varki A. Nature. 2007;446:1046. doi: 10.1038/nature05816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balzarini J. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:237. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balzarini J. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2007;18:1. doi: 10.1177/095632020701800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K., Hiki Y., Odani H., Shimozato S., Iwaze H., Sugiyama S., Usuda N. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:580. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto H. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:2954. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haseley S.R., Kamerling J.P., Vliegenhart J.F.G. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002;218:93. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duverger E., Frison N., Roche A., Monsigny M. Biochimie. 2003;85:167. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hölemann A., Seeberger P.H. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004;15:615. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeberger P.H., Werz D.B. Nature. 2007;446:1046. doi: 10.1038/nature05819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werz D.B., Seeberger P.H. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:3194. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson S.R., Hsu T.L., Weerapana E., Kishikawa K., Simon G.M., Cravatt B.F., Wong C.H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7266. doi: 10.1021/ja0724083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond M.R., Kohler J.J. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:52. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H., Chokhawala H.A., Huang S., Cheng X. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2485. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satoh A., Matsumoto I. Anal. Biochem. 1999;275:268. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vila-Perelló M., Gutiérrez Gallego R., Andreu D. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1831. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canne L.E., Ferré-D’Amaré A.R., Burley S.K., Kent S.B.H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:2998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y., Kent S.B.H., Chait B.T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:1629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peri F., Dumy P., Mutter M. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:12269. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peri F., Nicotra F. Chem. Commun. 2004;6:623. doi: 10.1039/b308907j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decostaire I.P., Lelièvre D., Zhang H., Delmas A.F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7057. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brask J., Jensen K.J. J. Peptide Sci. 2000;6:290. doi: 10.1002/1099-1387(200006)6:6<290::AID-PSC257>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wahl F., Mutter M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;3:6861. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Both peptides were synthesized by Fmoc-based solid phase synthesis on a Rink MBHA resin (0.70 mmol g−1) using Fmoc chemistry at 0.1 mmol scale. An aliquot of each peptide–resin was deprotected and cleaved prior to the study, to ensure the sequence was satisfactorily assembled. In both cases, a highly homogeneous product (>95% by HPLC, m/z 606 and m/z 719, corresponding to the [M + H]+ ion of A and B, respectively) was obtained.

- 28.From Novabiochem (Läufelfingen, Switzerland).

- 29.Peptide–resin was treated with 95% TFA, 2.5% TIS, 2.5% H2O for 90 min at rt. After filtering off the resin, the cleavage solution was diluted with chilled tert-butyl methyl ether to precipitate the peptide, which was separated by centrifugation, solubilized in water, and lyophilized.

- 30.Gausepohl H., Kraft M., Frank R.W. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1989;34:287. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1989.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.