Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is an emerging viral infectious disease. The SARS outbreak in Singapore started in mid-March 2003. Emergency departments, being the primary portal of entry into the hospitals, had to come up with rapid strategic changes and modifications to accommodate and manage this public health problem effectively. This report discusses the changes in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Singapore General Hospital, the largest public, teaching and tertiary hospital in Singapore, during this outbreak. It will highlight the safety aspects and universal precautions undertaken, the changes to the triage system, working hours, admission policies, as well as the fluctuations in the patient load.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), outbreak, infectious disease, emergency department

Pneumonia, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases, malaria, measles and HIV/AIDS annually account for half of all premature deaths from infectious diseases. The situation is of course more urgent in developing countries. More ominous is the fact that the World Health Organization (WHO) has, in the last 20 years, reported 30, either new or re- emerging diseases. These include infections with Hantavirus, Marburg and Ebola viruses, diphtheria, meningitis, dengue and typhus. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) represents one such newly emerging illness.1

SARS represent a newly identified clinical illness linked to an outbreak of atypical viral pneumonia in the Guangdong province in China. The agent causing SARS is tentatively identified as a coronavirus. The incubation period is between 2 and 10 days and the illness begins with a prodrome of fever, often accompanied by headache, malaise, myalgia, and mild respiratory symptoms. This then progresses to a lower respiratory phase with dry nonproductive cough and/or dyspnea, which may be accompanied by or progress to hypoxemia. Between 10% to 20% of patients may require intubation and mechanical ventilation. The clinical picture is variable especially in the presence of comorbidity, amongst those on steroids, with immunocompromised states as well as advanced age.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

In Singapore, there are 6 public general hospitals and one of these is entirely dedicated for women and children. Singapore General Hospital is the largest public, teaching hospital in Singapore, which offers tertiary, multidisciplinary care. Services such as Neurosurgery, Cardiothoracic Surgery, and 24-hour percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty are available. The emergency department (ED) at Singapore General Hospital is one of the busiest in the country and handles approximately 120,000 visits annually. The ED is staffed by 12 emergency physicians, 22 medical officers, and 108 nursing staff. The department has 24-hour consultant coverage and it sees a wide range of cases, which include trauma, medical and surgical emergencies, as well as urgent ambulatory problems. There is a 30-bed short-stay emergency observation ward and an 8-bed Emergency Cardiac Care Unit, run by the emergency physicians.

As Singapore lies at the crossroads of Asia, and is one of the busiest air and sea hubs in the region, tourism is one of the major industries. As such, a certain proportion of the patients seen at the ED includes tourists and foreigners. There are also many expatriates working in the cosmopolitan city.

With the declaration by the WHO on the March 12, 2003 that SARS was recognized as a worldwide health threat, the ED has undergone some major reorganization. It was realized that the globalization and its unprecedented interconnectedness, made possible by fast, high volume international travel, is now making the spread of a new communicable disease a pressing issue.

Reorganization

With the public awareness it was expected that the ED would now have to handle a significantly increased workload. As such, the shift work system was changed from an 8-hour one to a 12-hour rotating one for all staff with immediate effect. The shifts were staggered to provide maximum cover during the expected peak periods. The roster was also made flexible such that with any major incidents, the departmental action plan could be activated without too much disruption. There were also a few reserved staff members who could be recalled at any time. All leave and off-duty days were put on hold temporarily.

It is interesting to note that as the department was adjusting to the new rigor and increased workload, the public’s perception began to change. As the epidemic situation apparently worsened, and as a cluster of SARS cases among health care workers was disclosed, the public became more reluctant to visit hospitals. This change in trend was immediately responded to and the shift system was changed to the usual 8-hour one, with the department staff being distributed into 4 groups. The staff were now working based on a team concept and there was minimal or no interaction between the groups. This was to minimize intergroup contact as much as possible and thus, reduce any possibility of the spread of infection between groups as well.

Personal protective equipment which included impervious gowns, scrubs, N95 masks (N95 masks are health care particulate respirator and surgical masks designed to provide respiratory protection for the user. There is filter efficiency level of 95% or greater against particulate aerosols free of oil. They are fluid resistant and disposable and satisfy the CDC criteria for M tuberculosis exposure control. They reduce the exposure to airborne particles ranging from 0.1 to >10.0 microns. N95 masks provide >99% bacterial filtration efficacy (BFE) against user-generated microorganisms.), protective eyewear, head covers, and gloves were made readily available in a central location within the department and it was mandatory for everyone to be properly attired at all times. There was also an increase in the number of biohazard disposal bags and bins provided throughout the department. Infection control specialists gave compulsory briefings to everyone to reinforce correct and safe practices. “Seal checks” for masks was also performed for all staff.

It was also compulsory for all medical and nursing staff performing certain duties to use the powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). These duties included resuscitation, intubation, extubation, insertion of a nasogastric tube, suctioning of respiratory secretions and obtaining laryngeal or throat swabs, because there was risk of transmission of infection during these procedures. The PAPR is a powered respirator system, which protects against the inhalation of harmful materials. Filtered air from a blower is generated at greater than 120 L/min and delivered via a hose to the face hood. Air exits through the exhalation valve. The PAPR is used over the N95 mask, eye goggles, and head cover. Relevant instructions on donning, removal, cleaning, and maintenance of the PAPR were also taught to all staff.

Two areas were designated for the consultation of cases suspected of SARS. The first was in the ambulatory consultation area, in a corner room, where the air-conditioning system had been turned off and the windows opened for better ventilation. Fans were used to cool and ventilate the room. The other area consisted of 2 cubicles in the critical care area (CCA). These were more suitable for nonambulatory patients. The heavy sliding doors between these cubicles and the other cubicles were kept closed at all times. Staff entering these areas and treating patients with suspected SARS changed their gowns, masks, and gloves upon exit. Two medical officers per shift were scheduled to provide consult for these suspected cases. This was done to minimize contact of such cases with staff members. As the number of patients with fever, cough, dyspnea, and a history of SARS exposure increased, more consultation rooms were required. As such, rapid retrofitting and redesign was performed in the ED to create and partition separate areas for these patients to be seen and treated. An entirely new “fever wing” was created in this way. This concept made it less likely for those with fever to mingle with the rest of the ED patients and personnel. These areas were also installed with a separate ventilation system.

All suspected and confirmed cases of SARS were transported to Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), another public hospital which has been designated by the Ministry of Health in Singapore, as the hospital for treatment of SARS patients. The public could call a specially designated SARS ambulance service, initiated by the Ministry of Health, to transport a suspected SARS patient to TTSH. This service was free with an easy access telephone number. The transport for suspected Singapore General Hospital ED patients would be done in specified Singapore General Hospital ambulances, where the driver and accompanying staff had to take universal precautions. On return, the ambulances were cleaned and wiped with disinfectant and then aired for at least 30 minutes.

Cleaning was stepped up in the department, as facility and equipment protection from contamination was a consideration here. The floors were now mopped at least once every hour by the housekeeping staff. All contaminated items were placed immediately in biohazard bags for disposal. All cleaners were also required to don protective gear.

Hospital task force

Singapore General Hospital set up a SARS taskforce immediately after the declaration of the outbreak. The Chairman of the hospital’s Medical Board chaired it. There were also representatives from various departments such as the ED, Staff Clinic, Intensive Care Units, Nursing, Infectious Diseases, Resource Acquisition, as well as Operations and Communications. The taskforce has the responsibility to command all elements and resources, and make necessary decisions on issues pertinent to the SARS outbreak. An operations center was set up and it functioned from 9 am till 10 pm daily. A hotline number was also introduced for any queries and issues pertaining to the subject.

The taskforce members and hospital staff helped to set up some isolation wards with reverse barrier nursing. Certain ICU beds were reserved for critically ill SARS/suspected SARS patients. Administrative staff on the taskforce helped to set up a “SARS corner” on the hospital intra- and internet. Here, the information was updated daily and all the latest issues, articles and census were included. The taskforce members worked closely with the national committee from the Ministry of Health. Daily temperature census, newsletters with incident updates and group paging with safe practices messages now became the norm. Announcements pertaining to the safe practices were also highlighted through the hospital announcement system several times a day, to reinforce these to all staff.

Staff management

Risk assessment, which included the evaluation of the possible hazards and vulnerabilities of all staff were undertaken by senior members of the ED. Besides the change in shift hours, all staff had to use impervious gowns, N95 masks and scrubs when performing clinical duties. They were to change at the designated area immediately on entering the department. Those not adequately attired were not allowed in the patient care areas. These included doctors, nurses, radiographers, health care attendants, clerical staff, and research associates. Universal precautions guidelines were applicable to everyone without exceptions. Practices such as use of disposable equipment, disinfecting the chest piece of the stethoscope with alcohol swabs after every encounter with any patient and inanimate objects became the norm for everyone.

Staff on duty had to have their temperature checked when coming on and going off duty, and whenever they felt unwell. They had to change their gowns and masks every 6 hours when on duty or whenever there was contamination. Extra changing rooms and shower areas were provided. Meals had to be taken in a special lounge area in the department and no one was allowed to go to the hospital cafeteria during their shifts.

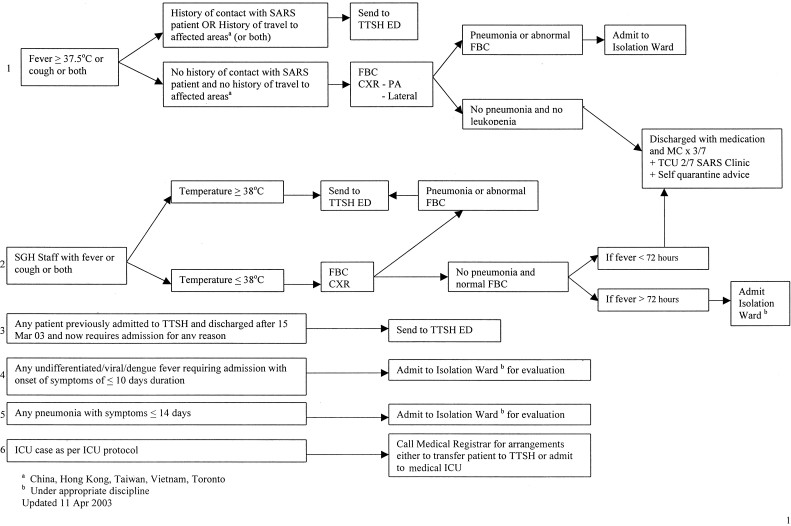

Any staff with fever and upper respiratory tract infection symptoms had to report sick immediately and was seen in the staff clinic. Here, their management had to adhere to the hospital’s guidelines (Fig 1). Administrative surveillance of all staff was a serious issue. Any staff who had managed high risk or suspected SARS cases would be monitored closely for 2 weeks for the development of symptoms. Their names were entered into a register in the department which was updated daily. A hundred percent compliance required extra effort initially, but with discipline and reinforcements this was achieved.

FIGURE 1.

SGH EDs algorithm for the management of the potential SARS case. TTSH, the designated “SARS hospital.”

Thermometers were issued to all staff so they could monitor their own temperatures even when they were at home. Notification of suspected and probable cases of SARS was mandatory under the Infectious Diseases Act. This was done electronically or by faxing the details to the Ministry of Health, as soon as the patient had been seen. Contact tracing was performed at both the departmental as well as the national level. This was made possible and more accurate as all the staff of the ED was given contact log books for them to chart all their contacts and visitations on a timely basis.

The staff clinic

This was set up in 1995 to attend to sick staff at Singapore General Hospital. During the SARS crisis, its role had to be expanded to include provision of screening for some public members as well as relatives with the history of contact with the patients who were admitted to the hospital. The daily attendance increased significantly and the operation hours were extended up to 10 pm, from the usual 5 pm. Doctors and nurses in this clinic were subjected to the same universal precautions and dress code as the rest of the staff in the ED.

Triage

Temperature taking stations were set up at the entry points into the department. Paramedical staff and health care assistants were given instructions pertaining to the hospital’s regulations. When taking body temperature at triage, the aural route (tympanic membrane temperature) was now used instead of the oral route to reduce contamination with respiratory droplets and secretions. Those with fever (≥37.5°C) had to be reassessed with further details before being allowed entry into the department. Nurses performing triage had the same dress code as everyone else in the department. The nurses performing triage were briefed on their history taking techniques so as to be able to identify high risk and suspected cases of SARS. Guidelines from the WHO,7 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA,8 the Ministry of Health, Singapore and the SARS Taskforce of Singapore General Hospital were taken into account.9 A questionnaire to assess risk factors was constructed for use at triage on all patients and accompanying relatives (Table 1). On identification of a high-risk or suspected SARS patient, doctors were alerted and the patient was then sent to the respective designated areas for complete consultation and examination. The appropriate investigations were also done. Several suspected cases were identified by the use of this questionnaire. All patients in the department had to use the surgical mask immediately at triage. Educational information and pamphlets were also distributed to enhance awareness.

TABLE 1.

SARS Screening Questionnaire

| To the best of my knowledge, in the past 2 weeks; | |

|---|---|

| Had fever. If Yes, state date and temperature. | Yes/No |

| Had cough. If Yes, state date. | Yes/No |

| Had contact with any SARS patient or “suspected SARS” cases. Give relationship and date. | Yes/No |

| Had traveled overseas. State country and dates. | Yes/No |

| Visited Tan Tock Seng Hospital or Communicable Diseases Centre. If Yes, State date and reasons. | Yes/No |

| Been to any of the public hospitals/private hospitals/polyclinics/private clinics. Specify date and reasons. | Yes/No |

Note. Tan Tock Seng Hospital is the local hospital designated for the treatment of SARS patients. These questions were repeated for all accompanying persons as well.

After triage, patients were classified as, “suspected SARS”, “caution case,” or a “normal risk patient.” The definitions are as follows:

-

I“suspected SARS”Those with unexplained fever (≥38°C) and

-

Aa history of close contact, within 10 days of onset of symptoms, with a person who has been diagnosed with SARS OR

-

Bhistory of travel within 10 days of onset of symptoms, to an area with reported foci of transmission of SARS.

-

A

-

II

“caution case”Those with unexplained fever (≥38°C).

-

III

“normal risk cases”There is no fever or fever <38°C and mild upper respiratory tract infection symptoms such as cough.

Workload

The daily attendance at the ED increased from an average of 330 to about 500 during the early period of the outbreak. Despite this increase of about 30%, the department was able to improve waiting times for all categories of patients. The reason for this was the rapid implementation of the 12-hour rotating shift system once the outbreak was declared. The attendance at the ED now consisted of (1) the usual group of patients seeking emergency treatment, (2) an increase in emergency ambulance case workload, and (3) an increase in the number of public seeking treatment for respiratory tract symptoms. The number of patients arriving via the emergency ambulance service was higher during this period as one of the public hospitals in Singapore, had been designated as the hospital for treatment and hospitalization of SARS patients only. As such, this hospital did not take in any of the emergency ambulance cases. These were then diverted to other public hospitals and Singapore General Hospital, being one of the major public hospitals, received a bigger share of these patients. For the period March 20 to April 10, inclusive (ie, 21 days), the department received a total of 1,518 emergency ambulance cases. This gave an average of about 72 emergency ambulance cases per 24 hours.

With this increased workload, extra staff members were seconded from some of the other departments in the hospital to help in the ED. To maintain order with the greater number of people in the ED overall, security and police officers helped with patient flow. They also set up checkpoints at all the entrances to the ED to screen arrivals.

As more SARS cases were diagnosed among health care workers, the number of visits to the ED was reduced, averaging around 200 patients per day. This was the result of the change in the public’s perception and hence, the reluctance to visit hospitals. This dwindling numbers did not last for long, as after a week, the attendance soared once more.

During this outbreak, all patients with a history of fever and chest infection were admitted to isolation wards, even though not suspected of having SARS, to cater for missed diagnosis. The Ministry of Health implemented and the hospitals enforced a “no visitor” rule for all patients during this period. A virtual visitors’ center was set up for relatives to communicate with their loved ones via videophones.

Supplies and logistics

There was a need to ensure adequate existing medical caches and equipment. Personnel equipment (eg, gowns and masks) needed to be supplied to all staff. Stockpiles could be depleted rapidly and thus, early anticipation of the expected increased demand alerted relevant personnel to purchase the items in timely fashion. During that time, alternative sources were sought.

During peak periods, demand for trolleys and wheelchairs exceeded the numbers available in the department. As such, there was an action plan to obtain some of these items from the operating theatres. Other products where utilization rates had gone up included biohazard bins and bags, antiseptic wipes, and cleaning solutions.

Teaching and other programs

Singapore General Hospital is the largest teaching hospital in Singapore and as such, with the SARS outbreak, numerous programs and teaching sessions had to be postponed, curtailed, or cancelled. Teaching in the ED was restricted to minimal and activities such as journal clubs and case conferences were cancelled. In March and April 2003, the ED had to delay attachments for some of the following;

-

1.

Basic trainee nurses attachment

-

2.

Masters in Nursing students

-

3.

Overseas and local elective medical students

-

4.

Fourth year medical students’ Emergency Medicine rotation and

-

5.

Premedical college students’ attachment

This was made possible with the cooperation and understanding of the deans and heads of these institutions of higher learning. Training programs and classes such as Basic Cardiac Life Support and First Aid also had lower attendance. A planned mass Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) training session for the public had to be delayed as well. Several members of the research staff were requested to stay away form the hospital during this outbreak.

Conclusions

As in most disasters or major incidents, the ED always bears the brunt of accepting and treating patients with any major health problems. The ED represents the primary portal of entry into any hospital. Thus, emergency physicians and all ED staff play a crucial and central role in the identification, subsequent management and correct referral to a designated SARS hospital. The ability to expeditiously respond to such an event depends on the state of preparedness of the ED and its staff. Their ability to adapt rapidly to the changes in working hours, dressing style, as well as functional and structural reorganization in the ED, is sine qua non. The close surveillance, extra efforts, and full-hearted compliance with protocols by everyone played a crucial role in the control of SARS in Singapore.

Hospitals and EDs must be prepared to handle unanticipated health and medical crisis, both on short- and long-term basis. Implementation of infection control measures is an important requirement for all health care workers. The practices described here were common to all the public hospitals and EDs. During this outbreak, with the timely and strict implementation of these practices, we are happy to report that no staff from the ED contracted SARS.

References

- 1.Gopalakrishna G., Choo P., Leo Y.S. SARS transmission and hospital containment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(3):395–400. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with SARS. New Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. Accessed from URL: www.nejm.org on 20 April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peiris J., Lai S., Poon L. Coronavirus as a possible cause of SARS. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Update: Outbreak of SARS worldwide, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:241–246. 248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78:86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78:81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2003. Accessed April 3, 2003 at www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Case definitions for surveillance of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) WHO; Geneva: 2003. Accessed April 3, 2003 at www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefinition. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health, Singapore Information for Healthcare Professionals. 2003 Available at app.moh.gov.sg. Accessed April 4. [Google Scholar]