Graphical abstract

A series of 2-substituted benzoxazinones were synthesized and showed significant effect to anti-human coronavirus and ICAM-1 expression inhibition.

Keywords: Benzoxazinones, Anti-HCoVs, ICAM-1

Abstract

A series of 2-substituted benzoxazinones were synthesized and subjected to anti-human coronavirus and ICAM-1 expression inhibition assays. Among them, compounds 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 exhibited significant anti-HCoV activities, and the IC50 value of these compounds are 6.08, 5.06, 6.83, 1.92, 7.59, and 5.79 μg/mL, respectively. Furthermore, compounds 1 and 6 showed significant inhibitory effect on ICAM-1 expression, the ED50 values of 1 and 6 are 1.00 and 0.50 μg/mL, respectively.

1. Introduction

Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) are major causes of upper respiratory tract illness in humans. Recently, a novel HCoV was found to induce severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) by action of the spike protein of coronavirus to mediate infection of target cells.1 Patients with SARS-associated coronavirus infection could develop atypical pneumonia with fulminant pulmonary edema. Additionally, more than 2000 people have died of this disease during the last two years. Therefore, research and development of an anti-HCoV agent is an important way to control disease. Generally, there are three targets for developing anti-viral agents,2 (1) inhibitors of virus entry and membrane fusion, (2) protease inhibitors to inhibit cleavage of the viral polymerase protein and viral RNA synthesis, and (3) nucleoside inhibitors to block viral replication. Among them, the inhibitors of HCoV (or SARS-CoV) proteinase and anti-HCoV agents are attractive targets for treating SARS now.3 Therefore, L-700,417, a HIV-1 protease, and sabadinine, a natural product isolated from Veratrum sabadilla, were considered as inhibitors of the SARS-CoV proteinase based on computational modeling evaluation.[4], [5] Additionally, glycyrrhizin, a natural component of traditional Chinese medicine from Glycyrrhiza uralensis, was demonstrated to inhibit the replication of SARS-CoV.6 On the other hand, HCoVs and their associate viruses usually induced pulmonary inflammation. While the inflammation was induced by virus, a key event (leukocyte extravasation through the endothelium) is the local activation of endothelial cells, as indicated by the expression of adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin.7 Therefore, in our research on anti-HCoV and anti-inflammatory agents from natural sources and their derivatives, we found the dianthranthramide derivatives, benzoxazinones, exhibited anti-HCoV and anti-inflammatory effects.

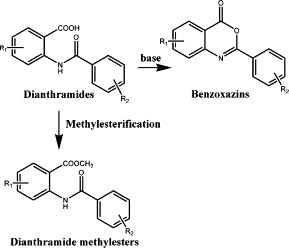

Dianthramides as phytoalexin were isolated from Dianthus species of Caryophyllaceae, while these plants were infected by Phytophthora parasitica.8 The carboxylic function of the anthranilic acid in dianthramides skeleton can be free (dianthramide A), methylesterified (dianthramide B), or implicated in a 2-substituted benzoxazinone heterocycle (dianthalexin) (Fig. 1 ).9 Among them, all analogues exhibited in vitro antifungal activity against P. parasitica.8 The 2-substitution benzoxazinones are also known as mechanism-based inhibitors of standard serine proteases of the chymotrypsin superfamily[10], [11] and inhibit by formation of an acyl–enzyme complex through attack of the active site serine on the carbonyl group.[12], [13] Therefore, the 2-substituted benzoxazinones showed bioactivities on human leukocyte elastase,[11], [14] C1r serine protease of the complement system,[15], [16] cathepsin G,17 human chymase,14 and tissue factor VIIa.18 Furthermore, there is interest that 2-substituted benzoxazinones could also be virtual protease inhibitors against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) protease18 and hCMV protease.20 As mentioned, we tried to research and develop 2-substituted benzoxazinones as anti-HCoV agents, and fortunately we found some analogues of benzoxazinones exhibited significant effect against HCoVs. In here, we report the preparation and preliminary screen data of anti-HCoV and ICAM-1 expression inhibition of these 2-substituted benzoxazinone analogues (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 1.

Dianthramides skeleton transformation.

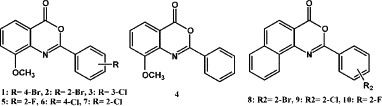

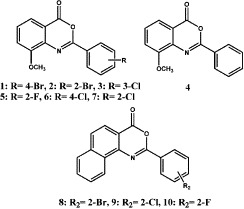

Figure 2.

The compounds 1–10 synthesized.

2. Chemistry

2-Phenyl-8-methoxy-benzoxazinones derivates, compounds 1–7 were prepared by reaction of 2-amino-3-methoxy-benzoic acid with corresponding substituted benzoyl chlorides. Compounds 8–10 were synthesized by reaction of 1-amino-naphthalene-2-carboxylic acid or 3-amino-naphthalene-2-carboxylic acid with corresponding substituted benzoyl chlorides. All products were fully characterized using spectral data (1H NMR, UV, IR, and MS).[21], [22]

3. Pharmacological evaluation and discussion

3.1. Anti-HCoV assays

Seventy microliters of MRC-5 cells (human fibroblasts cells, 1.0 × 105 cells/mL, in 3% FBS-DMEM medium) were cultured in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. 20 μL of HCoV (strain 229E, 20 TCID50/well) was added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Ten microliters of drug was added in triplicate in various concentrations. An XTT assay was used to determine the level of cell viability after 4 days incubation at 37 °C. Actinomycin D was used as a positive control.

3.2. ICAM-1 expression assays

This assay was performed using methods as described previously.7

3.3. Structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies

All synthesized 2-phenyl-benzoxazinone analogues were tested in parallel with Actinomycin D against HCoV, and the data are summarized in Table 1 . The active compounds were tested in ICAM-1 expression assays in advance. Among them, compounds 1 and 6 exhibited significant inhibition activities to ICAM-1 activation, the ED50 were 1.00 and 0.50 μg/mL, respectively. Furthermore, compounds 3, 4, 5, and 7 were inactive (ED50 > 10 μg/mL). According to these results, some structure–activity relationship could be proposed:

-

1.

2-Phenyl-benzoxazinones showed good anti-HCoV activity. Among them, compound 5 had the most potency on anti-HCoV assay.

-

2.

The bioactivities of anti-HCoV compounds decreased according to 2-phenyl group ortho-halogen substitution in the order F > Cl > Br

-

3.

The anti-HCoV activities of 2-phenyl naphtho[1,2-d][1,3] oxazin-4-ones 8, 9, and 10, which fused a benzene ring on the 7,8 positions of benzoxazinones, were nil.

-

4.

4′-Chloro- and 4′-bromo-2-phenyl benzoxazinones showed significant inhibitory effects to ICAM-1 expression. Ortho- and meta-halogen substituted analogues had no activity.

Table 1.

Anti-human coronavirus activity of compounds 1–10

| IC50 (μg/mL)a | |

|---|---|

| Actinomycin D | 0.02 |

| 1 | 6.08 ± 1.54 |

| 2 | Inactivity |

| 3 | 5.06 ± 0.08 |

| 4 | 6.83 ± 2.83 |

| 5 | 1.92 ± 0.36 |

| 6 | 7.59 ± 3.66 |

| 7 | 5.79 ± 1.12 |

| 8 | Inactivity |

| 9 | Inactivity |

| 10 | Inactivity |

The IC50 values are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

In conclusion, the compounds 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 exhibited significant activities to against human coronavirus. Moreover, compounds 1 and 6 were also showed impressive effects in the inhibition of ICAM-1 expression. This is the first report for benzoxazins as ICAM-1 inhibitors, and they also serve as anti-HCoV agents. These results propose a lead compound on research and development of anti-HCoV and ICAM-1 inhibition agents.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC92-2751-B-037-004-Y).

References and notes

- 1.Holmes K.V.N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1948–1951. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes K.V. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1605–1609. doi: 10.1172/JCI18819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziebuhr J., Herold J., Siddell S.G. J. Virol. 1995;69:4331–4338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4331-4338.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Higenfol R. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toney J.H., Navas-Martin S., Weiss S.R., Korller A. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1079–1080. doi: 10.1021/jm034137m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang C.H., Huang Y., Issekutz A.C., Griffith M., Lin K.H., Anderson R. J. Virol. 2002;76:427–431. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.427-431.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurosaki F., Naishi A. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:669–672. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponchet M., Favre-Bonvin J., Hauteville M., Ricci P. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:725–730. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedsrom L., Moorman A.R., Dobbs J., Abeles R.H. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1753–1759. doi: 10.1021/bi00303a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krantz A., Spencer R.W., Tam T.F., Liak T.J., Copp L.J., Thomas E.M., Rafferty S.P. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:464–479. doi: 10.1021/jm00164a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bode W., Meyer E., Jr., Powers J.C. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1951–1963. doi: 10.1021/bi00431a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers J.C., Asgian J.L., Ekici O.D., James K.E. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4639–4750. doi: 10.1021/cr010182v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann U., Schechter N.M., Gütschow M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:947–954. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hays S.J., Caprathe B.W., Gilmore J.L., Amin N., Emmerling M.R., Michael W., Nadimpalli R., Nath R., Raser K.J., Stafford D., Watson D., Wang K., Jaen J.C. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1060–1067. doi: 10.1021/jm970394d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmore J.L., Hays S.J., Caprathe B.W., Lee C., Emmerling M.R., Michael W., Jaen J.C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann U., Gütschow M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1997;5:1935–1942. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakobsen P., Pedersena B.R., Persson E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000;8:2095–2103. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvest R.L., Parratt M.J., Debouck C.M., Gorniak J.G., Jennings L.J., Serafinowska H.T., Strickler J.E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:2463–2466. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abood N.A., Schretzman L.A., Flynn D.L., Houseman K.A., Wittwer A.J., Dilworth V.M., Hippenmeyer P.J., Holwerda B.C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997;7:2105–2108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.General experimental procedure for the synthesis of compounds 1–7. To a pyridine solution of 2-amino-3-methoxy-benzoic acid (1.0 mmol) was added with corresponding substituted benzoyl chlorides. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h, respectively. The solvent was evaporated at reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Si-Gel) using CHCl3/Hexane (1:2∼1:1) mixture to afford the products. The 1H spectrum was recorded at 200 MHz using CDCl3 or CD3OD as solvent. 1: 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.86 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.60 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.22 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 155.9 (s, 3 × C), 134.8 (s), 132.7 (d, 3 × C), 130.5 (d, 2 × C), 128.0 (d), 127.6 (s), 127.0 (s), 123.2 (s), 116.2 (d), 56.7 (q); UV: 208, 238, 303 nm; IR (KBr): 1666, 1583, 1505, 1477, 1456, 1261, 1055, 1006, 747 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 333 (4), 31[M]+ (4); HREI-MS m/z: 330.9843 (calcd 330.9844). 2: 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.86 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 7.2 Hz, Ar–H), 7.84 (1H, dd, J = 1.2, 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.71 (1H, dd, J = 1.2, 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.52 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.42 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 7.2 Hz, Ar–H), 7.37 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.34 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 7.2 Hz, Ar–CH2), 4.02 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.8 (s), 156.3 (s), 154.4 (s), 136.5 (s), 133.8 (d), 132.6 (s), 132.0 (d), 131.5 (d), 129.2 (d), 127.2 (d), 121.7 (s), 119.5 (d), 117.8 (s), 117.5 (d), 56.5 (q); UV: 208, 223, 233, 276, 333 nm; IR (KBr): 1761, 1622, 1581, 1484, 1333, 1309, 1274, 1078, 1018, 752 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 331 [M]+ (7), 333 (7); HREI-MS m/z: 330.9852 (calcd 330.9844). 3: 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.16 (1H, br s, Ar–H), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.66 (1H, dd, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.41–7.10 (4H, m, Ar–H), 3.89 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.9 (s), 154.9 (s), 154.3 (s), 136.4 (s), 134.8 (s), 132.7 (s), 132.4 (d), 129.8 (d), 129.5 (s), 129.0 (d), 128.2 (d), 126.3 (d), 119.7 (d), 117.3 (d), 56.4 (q); UV: 206, 217, 245, 277 (sh), 292, 305, 345 nm; IR (KBr): 1762, 1616, 1573, 1484, 1330, 1306, 1275, 1229, 1060, 1023, 754 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 287 [M]+ (10), 289 (4); HREI-MS m/z: 287.0350 (calcd 287.0349. 4: 1H NMR(CDCl3): δ 8.40–8.30 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.81 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.62–7.50 (3H, m, Ar–H), 7.43 (1H, d,J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 4.03 (3H, s, OMe); UV: 205, 215, 245, 278 (sh), 290, 302, 331 (sh), 343, 358 (sh) nm; IR: 1749, 1617, 1574, 1484, 1451, 1336, 1277, 1228, 1054, 1026, 755, 687 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 253 [M]+ (34); HREI-MS m/z: 253.0735 (calcd 253.0739). 5: 1 H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.14 (1H, td, J = 1.8, 7.6 Hz, Ar–H), 7.83 (1H, dt, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.60–7.42 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.36–7.16 (3H, m, Ar–H), 4.04 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.9 (s), 158.9 (s), 154.4 (s), 154.3 (s), 137.0 (s), 133.8 (d), 131.1 (d), 129.0 (d), 124.2 (d), 124.1 (d), 124.0 (s), 119.6 (d), 117.9 (s), 117.5 (d), 56.6 (q); UV: 206, 213, 242, 288, 301 (sh), 339 nm; IR: 1757, 1612, 1575, 1484, 1452, 1333, 1274, 1220, 1105, 1023, 753 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 271 [M]+ (22); HREI-MS m/z: 271.0641 (calcd 271.0645). 6: δ 8.30 (1H, t, J = 1.4 Hz, Ar–H), 8.09 (1H, dt, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, Ar–H), 7.64 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, Ar–H), 7.54 (1H, ddd, J = 8.0, 2.0, 1.4 Hz, Ar–H), 7.34 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.24 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.19 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, Ar–H), 3.91 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.0 (s), 154.5 (s), 154.1 (s), 135.1 (s), 131.9 (s), 130.8 (C × 2, d), 129.9 (C × 2, d), 128.8 (d), 126.5 (d), 122.5 (s), 119.4 (d), 117.5 (s), 56.6 (q); UV: 211, 241 (sh), 278 (sh), 292, 305, 332 (sh), 345 nm; IR (KBr): 1766, 1692, 1615, 1575, 1561, 1483, 1333, 1304, 1272, 1229, 1057, 1024, 756 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 287 [M]+ (3), 289 (1); HREI-MS m/z: 287.0342 (calcd 287.0349). 7: 1H NMR(CDCl3): δ 7.85 (1H, br d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.78 (1H, dd, J = 0.8, 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.52–7.28 (5H, m, Ar–H), 3.97 (3H, s, OMe); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.9 (s), 155.7 (s), 154.4 (s), 136.3 (s), 133.3 (s), 132.0 (d), 131.4 (d), 131.4 (s), 130.7 (d), 129.2 (d), 126.7 (d), 119.5 (d), 117.9 (s), 117.5 (d), 56.5 (q); UV: 218, 239, 279 (sh), 333 nm; IR (KBr): 1757, 1621, 1578, 1486, 1332, 1309, 1275, 1226, 1082, 1022, 754 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 287 [M]+ (24), 289 (8); HREI-MS m/z: 287.0358 (calcd 287.0349)

- 22.General experimental procedure for the synthesis of compounds 8–10 To a pyridine solution of 1-amino-naphthalene-2-carboxylic acid or 3-amino-naphthalene-2-carboxylic acid (1.0 mmol) was added with corresponding substituted benzoyl chlorides. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h, respectively. The solvent was evaporated at reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Si-Gel) using CHCl3/hexane (1:3) mixture to afford the products. The 1H NMR spectrum was recorded at 200 or 400 MHz using CDCl3 as solvent. 8: 1H NMR: δ 8.97 (1H, m, Ar–H), 8.10 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 8.05 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.90 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 7.80–7.65 (3H, m, Ar–H), 7.47 (1H, dt, J = 1.2, 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.37 (1H, td, J = 7.8, 2.0 Hz, Ar–H); 13C NMR: δ 159.7 (s), 157.0 (s), 145.5 (s), 137.1 (s), 134.8 (C × 2, s, d), 132.4 (d), 131.8 (d), 131.4 (s), 130.2 (d), 129.2 (s), 129.0 (d), 127.8 (d), 127.6 (d), 127.4 (d), 125.6 (d), 122.1 (d), 112.9 (s); UV: 207, 253, 313, 324, 354 nm; IR (KBr): 1757, 1698, 1609, 1558, 1465, 1388, 1262, 1006, 757, 725 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 351 [M]+ (63), 353 (62); HREI-MS m/z: 350.9899 (calcd 350.9895). 9: 1H NMR δ 8.97 (1H, m, Ar–H), 8.14 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.92 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar–H), 7.80–7.69 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.68–7.40 (3H, m, Ar–H); 13C NMR: δ 159.6 (s), 156.6 (s), 145.6 (s), 137.1 (s), 133.9 (s), 132.4 (d), 131.7 (d), 131.5 (s), 130.2 (d), 129.6 (s), 129.2 (s), 129.0 (d), 127.9 (d), 127.6 (d), 126.8 (d), 125.6 (d), 122.2 (d), 112.9 (s); 207, 254, 312, 24, 354 nm; IR (KBr): 1762, 1612, 1561, 1471, 1389, 1263, 1012, 757, 729 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 307 [M]+ (89), 309 (24); HREI-MS m/z: 307.0397 (calcd 307.0400). 10: 1H NMR: δ 8.92 (1H, m, Ar–H), 8.29 (1H, dt, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, Ar–H), 8.09 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.94–7.84 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.80–7.57 (3H, m, Ar–H), 7.42–7.30 (2H, m, Ar–H); 13C NMR: δ 164.1 (s), 159.2 (s), 158.9 (s), 145.5 (s), 136.8 (s), 134.1 (d), 131.0 (d), 130.0 (d), 128.9 (s), 128.6 (d), 127.7 (d), 127.4 (d), 125.2 (d), 124.2 (d), 122.1 (d), 118.8 (s), 117.5 (d), 112.9 (s); UV: 207, 259, 312, 326, 356 nm; IR (KBr): 1751, 1616, 1561, 1454, 1305, 1217, 1017, 762, 742 cm−1; EI-MS m/z: 291 [M]+ (100); HREI-MS m/z: 291.0685 (calcd. 291.0696)