Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in older adults remains to be established.

Methods

Pneumonia patients aged ≥65 years who visited a study hospital in Chiba, Japan, were prospectively enrolled from February 2012 to January 2014. Sputum samples were collected from participants and tested for influenza virus by polymerase chain reaction assays. Influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia was estimated by a test-negative design.

Results

Among a total of 814 pneumonia patients, 42 (5.2%) tested positive for influenza: 40 were positive for influenza A virus, and two were positive for influenza B virus. The IVE against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia was 58.3% (95% confidence interval, 28.8–75.6%). The IVE against influenza pneumonia hospital admission, severe pneumonia, and death was 60.2% (95% CI, 22.8–79.4%), 65.5% (95% CI, 44.3–78.7%), and 71% (95% CI, −62.9% to 94.8%), respectively. In the subgroup analyses, the IVE against influenza pneumonia was higher for patients with immunosuppressive conditions (85.9%; 95% CI, 67.4–93.9%) than for those without (48.7%; 95% CI, 2.7–73%) but did not differ by patients’ statin use status.

Conclusion

IIV effectively reduces the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in older adults.

Keywords: Inactivated influenza vaccine, Vaccine effectiveness, Influenza pneumonia, Test-negative case-control design

1. Introduction

Influenza is a major public health concern for older adults. Influenza infections generally cause self-limited illnesses but can result in severe disease such as pneumonia in older adults with and without underlying conditions. Older age is associated with a higher risk of pneumonia and mortality in influenza patients [1]. Based on our recent estimates, the incidence of influenza pneumonia and its related mortality among people aged ≥65 years in Japan were 210 and 24 per 100,000 persons/year, respectively [2].

Cumulative evidence has suggested that influenza vaccines are effective at reducing the risk of medically attended influenza in children and adults [3], [4]. Currently, seasonal influenza vaccination is recommended for older adults in more than 90 countries [5]. However, its clinical benefit has long been discussed because vaccine responses are reduced by an age-related decline in adaptive immunity [6], [7]. Positive results have been reported from recent meta-analyses: influenza vaccines reduce medically attended influenza by 20–44% [8] and influenza-associated hospitalization by 37% in older adults [9]. However, evidence is lacking for the protective effect of influenza vaccination on influenza pneumonia, including primary influenza pneumonia and secondary bacterial pneumonia. In a study by Grijalva et al, influenza vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization from laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia by 56.7%, although the majority of their patients were people aged <65 years [10]. Therefore, the influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in older adults remains to be established.

We conducted this study to investigate the effectiveness of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and its related outcomes in adults aged ≥65 years. We also conducted subgroup analyses to explore differences in IVE by patient characteristics, particularly those related to immunosuppressive status.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and patients

This single-center prospective study was conducted at Kameda Medical Center (KMC), Kamogawa, Chiba, Japan, as part of the Adult Pneumonia Study Group-Japan (APSG-J) Study [2], [11], [12], [13]. The APSG-J Study was a multicenter prospective study of adult pneumonia conducted at four community-based hospitals in Japan from September 2011 to August 2014. To investigate IVE, influenza vaccination history was systematically collected at KMC. In this study, pneumonia patients aged ≥65 years who visited KMC from February 2012 to January 2014 were included. The diagnosis of pneumonia was made by staff physicians according to clinical signs, symptoms, and radiological findings. Demographic and clinical information was collected from patients and medical charts. Sputum samples were collected from patients at the time of enrollment. If the patient was unable to cough up sputum, sputum was induced with the inhalation of hypertonic saline solution. Details of study settings and designs have been described previously [2], [13].

2.2. Laboratory confirmation of influenza and other viruses

Gram staining and sputum culture were performed on site. Sputum samples were transferred to the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, and tested by in-house multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays to identify the influenza virus (A and B) and 11 other viral pathogens (respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], human metapneumovirus, human parainfluenza virus types 1–4, human rhinovirus [HRV], human coronavirus 229E/OC43, human adenovirus, and human bocavirus) [14]. The detection limits of the multiplex PCR assays were 10–100 copies per reaction as reported previously [14]. Influenza virus subtyping was performed for influenza A-positive samples via RT-PCR of the influenza HA genes using previously published methods [15], [16].

Patients were defined as having laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia if their sputum sample tested positive for influenza A or B virus by PCR. Influenza pneumonia patients were classified as having influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia if their sputum samples were microscopically purulent (i.e., Geckler's classification groups 4 and 5) and tested positive for bacterial pathogens by culture or PCR; otherwise, they were classified as having primary influenza pneumonia.

2.3. Cases and controls

A test-negative design (TND) case-control study was applied to estimate IVE [17]. Unlike the conventional case-control design, the TND does not require non-disease controls; instead, in this study design, researchers collect clinical samples from patients with a specific condition (eg, influenza like illnesses) and classify the patients into cases (i.e., influenza tested positive patients) and controls (i.e., influenza tested negative patients) according to the influenza test results. The TND is less susceptible to bias due to differences in health care-seeking behavior among cases and controls and provides reliable IVE estimates [18], [19]. Recently, TND studies have been widely used to estimate IVE against medically attended influenza and influenza-associated hospitalization [8], [9].

In the current study, our primary outcome was laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia. Cases were pneumonia patients who tested positive for influenza A or B, and controls were pneumonia patients who tested negative for both influenza A and B. The odds of vaccination were compared between cases and controls, and IVE was expressed as (1-odds ratio) × 100%. Our secondary outcomes were (1) primary influenza pneumonia, (2) influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia, (3) influenza pneumonia-related hospital admission, (4) severe influenza pneumonia, and (5) influenza pneumonia death.

2.4. Influenza vaccination status

In Japan, all adults aged ≥65 years are recommended by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare to receive one dose of the seasonal influenza vaccine [20]. The trivalent IIV vaccine was used during the study period (2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 seasons); the quadrivalent IIV vaccine was introduced in the 2015–16 season. High-dose or adjuvanted IIVs have not been licensed in Japan. The compositions of the trivalent IIV vaccines used during the study seasons and their antigenic match status are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Influenza vaccination histories were collected from medical records and confirmed by patients and/or their guardians. Patients were considered vaccinated for influenza if they had received at least one dose of influenza vaccine in the 12 months before the hospital visit. Because the duration from influenza vaccination to the hospital visit was recorded as a monthly data, all patients who had been vaccinated within a month were considered vaccinated in our primary analysis. Patients were considered as having unknown influenza vaccination statuses if their influenza vaccination histories were not recorded in medical charts and could not be confirmed by the patients or their guardians; this group was excluded from our primary analysis.

2.5. Procedures

Patients were categorized into three age groups: 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and 85 years or older. Patient disability status was evaluated using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score [21]. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was classified as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), or overweight (≥25.0). Chronic conditions included diabetes mellitus, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, liver disease, renal disease, neurological disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, and previous tuberculosis disease. Immunosuppressive status included cancer, oral steroid use, and immunosuppressive drug use. Patients were considered to have severe pneumonia if they required oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, or a vasopressor after admission. The period from November to April was considered the influenza season.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The characteristics of patients were compared according to influenza infection status (i.e., influenza pneumonia vs. non-influenza pneumonia) and influenza vaccination status (i.e., vaccinated vs. unvaccinated) using chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for numerical variables. IVE was estimated using logistic regression models. Pre-specified confounding factors were sex, age, the presence of chronic conditions, the presence of immunosuppression, smoking status, the duration from onset to hospital visit, and the period of the study, and all these variables were included in the final multivariable logistic regression models. We also considered the performance status score and BMI category as potential confounders and examined if IVE estimates changed after adjusting for these variables. Confidence intervals (CIs) were adjusted for the residential area level clustering of patients using robust standard errors.

We conducted sensitivity analyses as follows: (1) restricting the analysis to patients who visited during influenza seasons; (2) excluding patients vaccinated <1 month prior to hospital visit; (3) excluding patients vaccinated >6 months prior to hospital visit; (4) using patients who were negative for influenza virus but positive for non-influenza respiratory viruses as controls; (5) using patients who were negative for all viruses as controls [22]; (6) using propensity scores for adjustment; and (7) including patients with unknown vaccination status using multiple imputation.

Stratified analyses were conducted to investigate the potential effect modifications by patient characteristics (i.e., sex, age group, underlying condition, immunosuppressive status, and statin use status). Stratum-specific IVE estimates were compared using a likelihood ratio test (test for interaction).

2.7. Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan and the IRB of Kameda Medical Center, Chiba, Japan. Anonymized data were used in this study.

3. Results

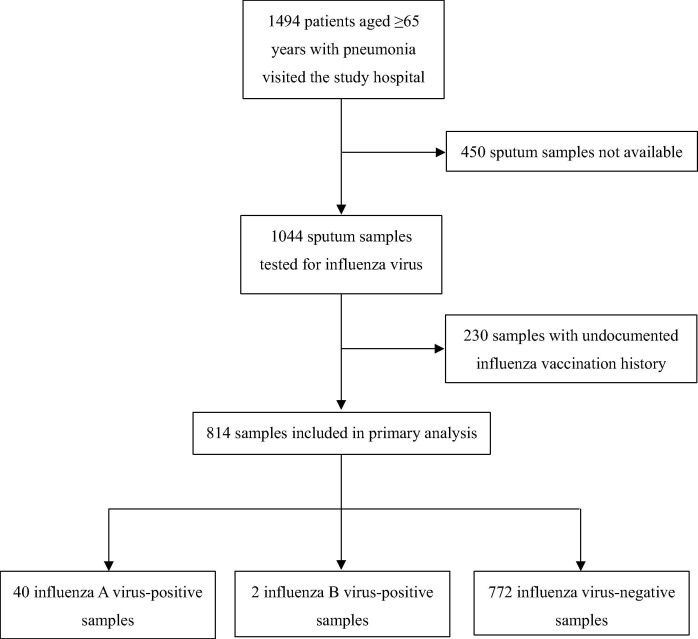

During the study period, a total of 1494 pneumonia patients aged ≥65 years were enrolled in the study. Among them, sputum samples were obtained from 1044 patients (70%). After excluding 230 patients whose influenza vaccination history were unavailable (22% of patients with sputum samples), a total of 814 patients were eligible for our analyses (Fig. 1 ). Among them, 42 (5%) tested positive for influenza virus by PCR: 40 were positive for the influenza A virus, and the other two were positive for the influenza B virus. Among the 26 influenza A-positive samples that were subtyped (65% of all influenza A-positive samples), all were positive for the H3N2 strain. Non-influenza viruses were detected in 178 patients: HRV was the leading virus detected (n = 77, 9%), followed by RSV (n = 36, 4%). Non-influenza viruses were co-detected in 6 of the 42 influenza-positive patients (14%) and detected in 172 of the 772 influenza-negative patients (22%). Bacterial pathogens were co-detected in 26 of the 42 influenza-positive patients (62%).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between influenza pneumonia patients (i.e., cases) and non-influenza pneumonia patients (i.e., controls) (Tables 1 and 2 ). Cases were more frequently found in winter seasons than controls, but other characteristics were similar between cases and controls.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants by influenza infection and vaccination status.

| By case status, n (%) |

By vaccination status, n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-influenza pneumonia (n = 772) | Influenza pneumonia (n = 42) | P valuea | Unvaccinated (n = 289) | Vaccinated (n = 525) | P valuea | |

| Age group, years | ||||||

| 65–74 | 199 (25.8) | 8 (19.1) | 0.619 | 78 (27.0) | 129 (24.6) | 0.732 |

| 75–84 | 333 (43.1) | 20 (47.6) | 124 (42.9) | 229 (43.6) | ||

| 85+ | 240 (31.1) | 14 (33.3) | 87 (30.1) | 167 (31.8) | ||

| Female sex | 306 (39.6) | 21 (50.0) | 0.182 | 106 (36.7) | 221 (42.1) | 0.131 |

| No. of children aged <5 y at home | ||||||

| 0 | 673 (87.2) | 36 (85.7) | 0.636b | 253 (87.5) | 456 (86.9) | 0.959 |

| 1+ | 49 (6.4) | 4 (9.5) | 18 (6.2) | 35 (6.7) | ||

| Unknown | 50 (6.5) | 2 (4.8) | 18 (6.2) | 34 (6.5) | ||

| Long-term care needed | 191 (24.7) | 11 (26.2) | 0.832 | 67 (23.2) | 135 (25.7) | 0.424 |

| Period of hospital visit | ||||||

| Feb 2012-Apr 2012 | 62 (8.0) | 11 (26.2) | <0.001b | 23 (8.0) | 50 (9.5) | 0.668 |

| May 2012-Oct 2013 | 157 (20.3) | 3 (7.1) | 61 (21.1) | 99 (18.9) | ||

| Nov 2012-Apr 2013 | 233 (30.2) | 25 (59.5) | 97 (33.6) | 161 (30.7) | ||

| May 2013-Oct 2013 | 202 (26.2) | 2 (4.8) | 66 (22.8) | 138 (26.3) | ||

| Nov 2013-Jan 2014 | 118 (15.3) | 1 (2.4) | 42 (14.5) | 77 (14.7) | ||

Chi-square tests were performed unless otherwise indicated.

Fisher’s exact test.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of study participants by influenza infection and vaccination status.

| By case status, n (%) |

By vaccination status, n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-influenza pneumonia (n = 772) | Influenza pneumonia (n = 42) | P valuea | Unvaccinated (n = 289) | Vaccinated (n = 525) | P valuea | |

| Home oxygen therapy used | 71 (9.2) | 3 (7.1) | 1b | 12 (4.2) | 62 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| BMI categories | ||||||

| Underweight | 205 (26.6) | 12 (28.6) | 0.87b | 84 (29.1) | 133 (25.3) | 0.251 |

| Normal | 372 (48.2) | 21 (50.0) | 126 (43.6) | 267 (50.9) | ||

| Overweight | 91 (11.8) | 3 (7.1) | 35 (12.1) | 59 (11.2) | ||

| Unknown | 104 (13.5) | 6 (14.3) | 44 (15.2) | 66 (12.6) | ||

| Current/ex-smoker | ||||||

| Yes | 427 (55.3) | 20 (47.6) | 0.482b | 154 (53.3) | 293 (55.8) | 0.285 |

| No | 329 (42.6) | 21 (50.0) | 126 (43.6) | 224 (42.7) | ||

| Unknown | 16 (2.1) | 1 (2.4) | 9 (3.1) | 8 (1.52) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Bronchial asthma | 56 (7.3) | 6 (14.3) | 0.094 | 21 (7.3) | 41 (7.8) | 0.78 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 201 (26.1) | 12 (28.6) | 0.716 | 56 (19.4) | 157 (30.0) | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 74 (9.6) | 4 (9.5) | 1b | 33 (11.4) | 45 (8.6) | 0.187 |

| Heart failure | 118 (15.3) | 10 (23.8) | 0.139 | 38 (13.1) | 90 (17.1) | 0.134 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 194 (25.1) | 7 (16.7) | 0.215 | 74 (25.6) | 127 (24.2) | 0.654 |

| Chronic renal disease | 70 (9.1) | 5 (11.9) | 0.536b | 23 (8.0) | 52 (9.9) | 0.358 |

| Chronic liver disease | 26 (3.4) | 2 (4.8) | 0.651b | 14 (4.8) | 14 (2.7) | 0.103 |

| Cancer | 159 (20.6) | 5 (11.9) | 0.171b | 57 (19.7) | 107 (20.4) | 0.823 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 153 (19.8) | 8 (19.0) | 0.903 | 58 (20.1) | 103 (19.6) | 0.877 |

| Dementia | 109 (14.2) | 7 (16.7) | 0.646 | 36 (12.5) | 80 (15.2) | 0.277 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Oral steroids | 86 (11.1) | 6 (14.3) | 0.531 | 29 (10.0) | 63 (12.0) | 0.397 |

| Immunosuppressants | 16 (2.1) | 1 (2.4) | 0.597b | 7 (2.4) | 10 (1.9) | 0.621 |

| Statins | 129 (16.7) | 7 (16.7) | 0.994 | 51 (17.7) | 85 (16.2) | 0.594 |

| Time from disease onset to hospital visit ≥4 days | 287 (37.2) | 17 (40.5) | 0.667 | 111 (38.4) | 193 (36.8) | 0.642 |

| Influenza vaccinated ≤12 months prior to the hospital visit | 506 (65.5) | 19 (45.2) | 0.007 | |||

| Time from influenza vaccination to hospital visit, months, median (IQR) | 5 (6) | 3 (2) | 0.003c | 5 (6) | ||

Chi-square tests were performed unless otherwise indicated.

Fisher’s exact test.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Among 814 patients, 525 (65%) had been vaccinated for influenza. Vaccinated patients more frequently had received home oxygen therapy and had been diagnosed with chronic respiratory obstructive disease than unvaccinated patients, while other characteristics were similar between two groups (Tables 1 and 2).

After adjusting for confounders, the IVE against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia was 58.3% (95% CI, 28.8–75.6%) (Table 3 ). The change in IVE estimates was marginal after additional adjustment for performance status (58.9%; 95% CI, 30.6–75.7%) or BMI category (58.0%; 27.6–75.6%); therefore, these variables were not included in the final models. The sensitivity analyses showed similar results. IVE was relatively higher (68.9%; 95% CI, 46.4–81.9%) when we used patients who were negative for influenza but positive for non-influenza viruses as controls, but the value was almost identical to the primary analysis when we used patients who were negative for all viruses (57.8%; 95% CI, 26.9–75.7%).

Table 3.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness and sensitivity analyses.

| Cases who were vaccinated, No./Total No. | Controls who were vaccinated, No./Total No. | Crude vaccine effectiveness (95% CI) | Adjusted vaccine effectiveness (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Influenza pneumonia | 19/42 | 506/772 | 56.6 (25.8–74.6) | 58.3 (28.8–75.6) |

| Sensitivity analysis | ||||

| Restricted to influenza season (Nov-Apr) | 17/37 | 271/413 | 55.5 (19.1–75.5) | 57.1 (20.1–77) |

| Excluded patients vaccinated <1 month prior to hospital visit | 19/42 | 485/751 | 54.7 (22.1–73.6) | 55.8 (23–74.6) |

| Excluded patients vaccinated >6 months prior to hospital visit | 19/42 | 313/579 | 29.8 (−20.6 to 59.1) | 48 (8.4–70.5) |

| Controls positive for non-influenza viruses | 19/42 | 118/172 | 62.2 (32.2–78.9) | 68.9 (46.4–81.9) |

| Controls negative for all viruses | 19/42 | 388/600 | 54.9 (22.5–73.7) | 57.8 (26.9–75.7) |

| Propensity score-adjusted analysisb | 19/42 | 506/772 | 56.6 (25.8–74.6) | 60.1 (35.1–75.5) |

| Included patients with unknown vaccination statusc | Imputed/49 | Imputed/995 | 55.4 (27.2–72.6) | 59.2 (31.5–75.7) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Primary influenza pneumonia (without bacterial infection) | 6/16 | 506/772 | 68.5 (20.8–87.4) | 70.1 (19.8–88.9) |

| Influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia | 13/26 | 506/772 | 47.4 (13.1–68.2) | 49.1 (17.1–68.7) |

| Influenza pneumonia admission | 12/30 | 345/550 | 60.4 (25.3–79) | 60.2 (22.8–79.4) |

| Influenza severe pneumonia | 6/17 | 151/241 | 67.5 (46.8–80.1) | 65.5 (44.3–78.7) |

| Influenza pneumonia death | 2/7 | 27/47 | 70.4 (−40.7 to 93.8) | 71 (−62.9 to 94.8) |

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for sex, age, smoking status, chronic conditions, immunosuppressive conditions, duration of symptoms, and period of hospital visit.

Propensity scores were created using 34 variables including those for demographic characteristics and 15 comorbidities.

Two hundred thirty pneumonia patients whose influenza vaccination histories were not documented were included in the analysis. The vaccination histories of these patients were considered missing data, and multiple imputations were performed.

For the secondary outcomes, the IVE against primary influenza pneumonia (70.1%; 95% CI, 19.8–88.9%) was higher than that against influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia (49.1%; 95% CI, 17.1–68.7%). The IVE against influenza pneumonia-related hospital admission (60.2%; 95% CI, 22.8–79.4%) and severe influenza pneumonia (65.5%; 95% CI, 44.3–78.7%) was comparable to that against influenza pneumonia. The point estimate of IVE against influenza pneumonia death was also high (71%; 95% CI, −62.9% to 94.8%), but its CI was wide because of the limited sample size.

Stratified analyses are shown in Table 4 . The IVE against influenza pneumonia was higher in patients with immunosuppressive conditions (85.9%; 95% CI, 67.4–93.9%) than in those without these conditions (48.7%; 95% CI, 2.7–73%; test for interaction, p = 0.001). IVE did not differ by sex. The point estimate of IVE decreased with increased age, but the difference did not reach a statistically significant level (test for interaction, p = 0.17). Patients’ chronic conditions and statin use status did not modify IVE.

Table 4.

Stratified analysis of the influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza pneumonia.

| Cases who were vaccinated, No./Total No. | Controls who were vaccinated, No./Total No. | Adjusted vaccine effectivenessa (95% CI) | P value (test for interaction) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall estimate | 19/42 | 506/772 | 58.3 (28.8–75.6) | |

| Stratified by sex | ||||

| Male | 9/21 | 295/466 | 62.3 (12.7–83.7) | 0.802 |

| Female | 10/21 | 211/306 | 56.6 (13.7–78.2) | |

| Stratified by age group, years | ||||

| 65–74 | 3/8 | 126/199 | 80.2 (61.8–89.7) | 0.17 |

| 75–84 | 9/20 | 220/333 | 64.3 (4.8–86.6) | |

| 85+ | 7/14 | 160/240 | 38.3 (−27.4 to 70.1) | |

| Stratified by chronic conditionsb | ||||

| With chronic conditions | 16/35 | 418/632 | 57.2 (27–74.9) | 0.986 |

| Without chronic conditions | 3/7 | 88/140 | 70.2 (−51.5 to 94.1) | |

| Stratified by immunosuppressive conditionsc | ||||

| With immunosuppressive conditions | 3/10 | 158/234 | 85.9 (67.4–93.9) | 0.001 |

| Without immunosuppressive conditions | 16/32 | 348/538 | 48.7 (2.7–73) | |

| Stratified by statin use status | ||||

| Statin use | 2/7 | 83/129 | 74.2 (−39.9 to 95.3) | 0.617 |

| No statin use | 17/35 | 423/643 | 57.1 (24–75.8) | |

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for sex, age, smoking status, chronic conditions, immunosuppressive conditions, duration of symptoms, and period of hospital visit.

Chronic conditions included diabetes mellitus, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, liver disease, renal disease, neurological disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, and previous tuberculosis disease.

Immunosuppressive status included cancer, oral steroid use, and immunosuppressive drug use.

4. Discussion

IIV effectively reduced the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in adults aged ≥65 years. IVE was higher among patients with immunosuppressive conditions, while statins did not modify IVE. To our knowledge, this is the first study that confirmed the beneficial effect of seasonal influenza vaccination against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in older adults.

4.1. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in older adults

The benefit of seasonal influenza vaccination in older adults is still debated [3], [23]. In this age group, the age-related decline in adaptive immunity results in reduced responses to influenza vaccination [6], [7]; moreover, multiple chronic conditions and frailty may also contribute to weak immune responses [24]. However, despite an observed lower antibody response compared with that of younger adults [25], recent evidence supports the protective effect of influenza vaccination against medically attended influenza in older adults. According to a systematic review by Belongia et al, the pooled IVE was 24% (95% CI, −6% to 45%) for the H3N2 strain, 63% (95% CI, 33–79%) for type B, and 62% (95% CI, 36–78%) for the H1N1pdm09 strain among adults aged >60 years [4]. Darvishian et al conducted an individual participant data meta-analysis of TND studies and demonstrated that influenza vaccination is moderately effective against laboratory-confirmed influenza in this age group during epidemic seasons but not during non-epidemic seasons [8].

On the other hand, evidence is still limited for the beneficial effect of influenza vaccination against influenza-related severe outcomes such as pneumonia. Previous studies have estimated the IVE against all-cause pneumonia or influenza-related hospitalization in older adults [9], [26], [27], [28]; however, these studies used less specific outcomes and may have underestimated the true IVE [17]. The TND study by Grijalva et al demonstrated that the overall estimate of IVE against hospitalization with laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia was 56.7% (95% CI, 31.9–72.5%) [10]. However, their study included all age groups, and only 16% of their patients were aged ≥65 years. In their analysis restricted to patients aged ≥65 years, IVE showed a positive effect but did not reach a statistically significant level (48.4%; 95% CI, −33.3% to 80%). Therefore, the authors concluded that additional studies were needed to establish the IVE against pneumonia in older adults. Our study targeted this age group and demonstrated that the vaccine effectively reduces the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia by 58.3% (95% CI, 28.8–75.6%).

Our IVE estimates against influenza pneumonia in older adults may be higher than generally expected values. IVE is commonly lower for severe outcomes than for medically attended influenza and is lower in older adults than in children [3], [9]. In addition, IVE is usually lower for the H3N2 stain than for the H1N1pdm09 strain [4]. However, our estimates are not dissimilar to those of previous reports: in the study by Grijalva et al, the IVE against influenza pneumonia related to the H3N2 strain in all age groups was 45.1% (95% CI, −9.3% to 72.4%) [10], and in another study conducted during the 2011–12 influenza season when H3N2 was the dominant circulating strain, the IVE against influenza hospitalization in adults aged ≥65 years was 58.0% (95% CI, 34.2–73.2%) [29]. The use of sputum samples in our study may also explain our high IVE estimate. Identification of influenza from sputum samples may be more sensitive and specific than that from upper respiratory tract samples in diagnosing influenza pneumonia and may provide less biased IVE estimates [17], [30], [31]. Consistent findings in our sensitivity analyses also support the robustness of our IVE estimates.

4.2. Primary influenza pneumonia and secondary bacterial pneumonia

Although a higher IVE estimate was observed for primary influenza pneumonia, IIV was also effective at preventing influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia (49.1%; 95% CI, 17.1–68.7%). This finding is important because influenza-bacterial co-infection increases the risk of severe outcomes [32]. Our finding also suggests that IIV may be effective at preventing influenza pneumonia death; however, the association did not reach a statistically significant level because of the limited sample size.

4.3. Immunosuppressive conditions and statins

It was unexpected that the IVE was significantly higher among people with immunosuppressive conditions (85.9%; 95% CI, 67.4–93.9%) than among those without (48.7%; 95% CI, 2.7–73%). The opposite finding was observed in the study by Grijalva et al, which included children and adults (−21.9% vs. 73.4%) [10]. This difference might be, at least partially, explained by a lower HIV prevalence in our patients. Although seasonal influenza vaccinations have been recommended for adults with immunosuppressive conditions [33], only a few studies have evaluated the IVE against clinical outcomes among this population [34]. Our finding provides supporting evidence for the current recommendations but needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Recent studies have suggested that statins may reduce the IVE against medically attended influenza among older adults by their immunomodulatory effects [35], [36], [37], [38]. However, such an effect has not been observed in our study. Although the degree of its effect remains controversial, statins are also known to modify the risk of pneumonia and pneumonia-related outcomes [39], [40], [41]. The impact of statin use on the IVE may be different according to influenza outcomes.

4.4. Implications and future studies

Influenza infection is a threat to older adults because of its potential to cause pneumonia and secondary bacterial infections [13]. The burden of pneumonia is rapidly increasing in high-income countries such as Japan because of the aging population [2]. Therefore, the prevention of influenza pneumonia is an important public health measure in controlling pneumonia. The moderate effectiveness observed in our study supports the current seasonal influenza vaccination policy. In Japan, the proportion of people vaccinated against influenza among adults aged ≥65 years has been increasing but still remains approximately 60% [42]. In addition to improving vaccination coverage, an introduction of newer vaccines such as the more immunogenic high-dose influenza vaccine must be considered [43], [44]. On the other hand, it must be noted that only 5% of pneumonia cases have influenza pneumonia, and thus, the impact of influenza vaccination on all-cause pneumonia is limited [45]. Newer multidimensional approaches are needed to reduce the pneumonia burden in the aging population.

5. Limitations

Our study has limitations. Influenza vaccination history was not documented for 22% of our patients. However, our sensitivity analysis using multiple imputations showed very robust estimates. We believe that the exclusion of this patient group did not affect our IVE estimates. Although all potential confounders were considered, unmeasured confounders may have remained. Recently, Andrew et al argued that frailty must be considered in estimating IVE for older adults [29]. We have not measured the frailty of our patients but measured their performance status and BMI. We confirmed that the inclusion of performance status or BMI category in the final model did not change the IVE estimates. Our observation is based on the analyses of older patients aged ≥65 years and therefore may not be generalizable to younger adults. Finally, our sample size was too small to estimate subtype-specific IVE.

6. Conclusion

Seasonal influenza vaccination is moderately effective against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia in adults aged ≥65 years. Considering the increasing burden of pneumonia in an aging population, we must improve influenza vaccination coverage and establish newer approaches.

Conflicts of interest

Konosuke Morimoto reports speaker fees from Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, and Asahi Kasei Pharma. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MS KM. Data collection: NAK NOK MY NH YO MA KM. Analyzed the data: MS NAK MNL LMY KM. Wrote the paper: MS NAK KM.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the Adult Pneumonia Study Group-Japan contributors. We would like to thank Professor Koya Ariyoshi, Dr. Eiichiro Sando, and Dr. Tomoko Ishifuji for their contribution to the study. We also thank Rina Shiramizu, Kyoko Uchibori for performing the PCR and Yumi Araki for administrative work.

Funding sources

This study was supported by Nagasaki University and Pfizer Japan, Inc.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.037.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Mertz D., Kim T.H., Johnstone J., Lam P.P., Science M., Kuster S.P. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2013;347:f5061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morimoto K., Suzuki M., Ishifuji T., Yaegashi M., Asoh N., Hamashige N. The burden and etiology of community-onset pneumonia in the aging Japanese population: a multicenter prospective study. PloS One. 2015;10:e0122247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osterholm M.T., Kelley N.S., Sommer A., Belongia E.A. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belongia E.A., Simpson M.D., King J.P., Sundaram M.E., Kelley N.S., Osterholm M.T. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system; 2017.

- 6.Plowden J., Renshaw-Hoelscher M., Engleman C., Katz J., Sambhara S. Innate immunity in aging: impact on macrophage function. Aging Cell. 2004;3:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lord J.M. The effect of ageing of the immune system on vaccination responses. Hum Vaccines Immunotherap. 2013;9:1364–1367. doi: 10.4161/hv.24696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darvishian M., van den Heuvel E.R., Bissielo A., Castilla J., Cohen C., Englund H. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in community-dwelling elderly people: an individual participant data meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies. Lancet Resp Med. 2017;5:200–211. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rondy M., El Omeiri N., Thompson M.G., Leveque A., Moren A., Sullivan S.G. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in preventing severe influenza illness among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies. J Infect. 2017;75:381–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grijalva C.G., Zhu Y., Williams D.J., Self W.H., Ampofo K., Pavia A.T. Association between hospitalization with community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and prior receipt of influenza vaccination. Jama. 2015;314:1488–1497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishifuji T., Sando E., Kaneko N., Suzuki M., Kilgore P.E., Ariyoshi K. Recurrent pneumonia among Japanese adults: disease burden and risk factors. BMC Pulmonary Med. 2017;17:12. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0359-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki M., Dhoubhadel B.G., Ishifuji T., Yasunami M., Yaegashi M., Asoh N. Serotype-specific effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults aged 65 years or older: a multicentre, prospective, test-negative design study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:313–321. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katsurada N., Suzuki M., Aoshima M., Yaegashi M., Ishifuji T., Asoh N. The impact of virus infections on pneumonia mortality is complex in adults: a prospective multicentre observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:755. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2858-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida L.M., Suzuki M., Yamamoto T., Nguyen H.A., Nguyen C.D., Nguyen A.T. Viral pathogens associated with acute respiratory infections in central vietnamese children. Pediatric Infect Dis J. 2010;29:75–77. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181af61e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki M., Minh le N., Yoshimine H., Inoue K., Yoshida L.M., Morimoto K. Vaccine effectiveness against medically attended laboratory-confirmed influenza in Japan, 2011–2012 Season. PloS One. 2014;9:e88813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le M.N., Yoshida L.M., Suzuki M., Nguyen H.A., Le H.T., Moriuchi H. Impact of 2009 pandemic influenza among Vietnamese children based on a population-based prospective surveillance from 2007 to 2011. Influenza Other Resp Viruses. 2014;8:389–396. doi: 10.1111/irv.12244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orenstein E.W., De Serres G., Haber M.J., Shay D.K., Bridges C.B., Gargiullo P. Methodologic issues regarding the use of three observational study designs to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:623–631. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Wu XW, Ambrose CS. The test-negative design: validity, accuracy and precision of vaccine efficacy estimates compared to the gold standard of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = Eur Communicable Dis Bull 2013;18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Sullivan S.G., Tchetgen Tchetgen E.J., Cowling B.J. Theoretical basis of the test-negative study design for assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:345–353. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito N., Komori K., Suzuki M., Morimoto K., Kishikawa T., Yasaka T. Negative impact of prior influenza vaccination on current influenza vaccination among people infected and not infected in prior season: a test-negative case-control study in Japan. Vaccine. 2017;35:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oken M.M., Creech R.H., Tormey D.C., Horton J., Davis T.E., McFadden E.T. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki M., Camacho A., Ariyoshi K. Potential effect of virus interference on influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates in test-negative designs. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:2642–2646. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferson T., Di Pietrantonj C., Al-Ansary L.A., Ferroni E., Thorning S., Thomas R.E. Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004876.pub3. CD004876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer J.M., De Castro A., Bosco N., Romagny C., Diekmann R., Benyacoub J. Influenza vaccine response in community-dwelling German prefrail and frail individuals. Immun Ageing: I & A. 2017;14:17. doi: 10.1186/s12979-017-0098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin K., Viboud C., Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster D.A., Talsma A., Furumoto-Dawson A., Ohmit S.E., Margulies J.R., Arden N.H. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalization for pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:296–307. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monto A.S., Hornbuckle K., Ohmit S.E. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among elderly nursing home residents: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:155–160. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichol K.L., Nordin J.D., Nelson D.B., Mullooly J.P., Hak E. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in the community-dwelling elderly. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:1373–1381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrew M.K., Shinde V., Ye L., Hatchette T., Haguinet F., Dos Santos G. The importance of frailty in the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization in elderly people. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:405–414. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falsey A.R., Formica M.A., Walsh E.E. Yield of sputum for viral detection by reverse transcriptase PCR in adults hospitalized with respiratory illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:21–24. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05841-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong J.H., Kim K.H., Jeong S.H., Park J.W., Lee S.M., Seo Y.H. Comparison of sputum and nasopharyngeal swabs for detection of respiratory viruses. J Med Virol. 2014;86:2122–2127. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia L., Xie J., Zhao J., Cao D., Liang Y., Hou X. Mechanisms of severe mortality-associated bacterial co-infections following influenza virus infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:338. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez A., Mariette X., Bachelez H., Belot A., Bonnotte B., Hachulla E. Vaccination recommendations for the adult immunosuppressed patient: a systematic review and comprehensive field synopsis. J Autoimmun. 2017;80:10–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eliakim-Raz N., Vinograd I., Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A., Leibovici L., Paul M. Influenza vaccines in immunosuppressed adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008983.pub2. CD008983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black S., Nicolay U., Del Giudice G., Rappuoli R. Influence of statins on influenza vaccine response in elderly individuals. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1224–1228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omer S.B., Phadke V.K., Bednarczyk R.A., Chamberlain A.T., Brosseau J.L., Orenstein W.A. Impact of statins on influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean H.Q., Chow B.D., VanWormer J.J., King J.P., Belongia E.A. Effect of statin use on influenza vaccine effectiveness. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1150–1158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascitelli L., Goldstein M.R. How regulatory T-cell induction by statins may impair influenza vaccine immunogenicity and effectiveness. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1857. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janda S., Young A., Fitzgerald J.M., Etminan M., Swiston J. The effect of statins on mortality from severe infections and sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2010;25(656):e7–e22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chopra V., Rogers M.A., Buist M., Govindan S., Lindenauer P.K., Saint S. Is statin use associated with reduced mortality after pneumonia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2012;125:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Havers F., Bramley A.M., Finelli L., Reed C., Self W.H., Trabue C. Statin use and hospital length of stay among adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis: Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2016;62:1471–1478. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nobuhara H., Watanabe Y., Miura Y. Estimated influenza vaccination rates in Japan. [Nihon koshu eisei zasshi] Jpn J Publ Health. 2014;61:354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shay D.K., Chillarige Y., Kelman J., Forshee R.A., Foppa I.M., Wernecke M. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines among US medicare beneficiaries in preventing postinfluenza deaths during 2012–2013 and 2013–2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:510–517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gravenstein S., Davidson H.E., Taljaard M., Ogarek J., Gozalo P., Han L. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination on numbers of US nursing home residents admitted to hospital: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Resp Med. 2017;5:738–746. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferdinands J.M., Gargiullo P., Haber M., Moore M., Belongia E.A., Shay D.K. Inactivated influenza vaccines for prevention of community-acquired pneumonia: the limits of using nonspecific outcomes in vaccine effectiveness studies. Epidemiology. 2013;24:530–537. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182953065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.