Abstract

Spring viraemia of carp virus (SVCV) causes high morality in several economically important cyprinid fishes, but there is no approved therapy up to now. To address the urgent need for therapeutics to combat SVCV infection, we investigated the anti-SVCV activities of 12 natural compounds and 7 common antiviral agents using epithelioma papulosum cyprini (EPC) cells in this study. From the 19 compounds, we identified arctigenin (ARG) has the highest inhibition on SVCV replication, with maximum inhibitory percentage on SVCV > 90%. And the 48 h half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of ARG on SVCV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein were 0.29 (0.22–0.39) and 0.35 (0.29–0.41) mg/L respectively. In addition, ARG significantly reduced SVCV-induced apoptosis and recovered SVCV-activated caspase-3/8/9 activity. Further, cellular morphological damage induced by SVCV was blocked by ARG treatment. Mechanistically, ARG did not affect SVCV infectivity. Moreover, ARG could not induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which plays an antiviral role on SVCV. Interestingly, SVCV-induced autophagy which is necessary for virus replication was inhibited by ARG treatment. These results indicated that the inhibition of ARG on SVCV replication was, at least in part, via blocking SVCV-induced autophagy. Taken together, ARG has the potential to work as an agent for protecting economically important fishes against SVCV.

Keywords: SVCV, EPC cells, Apoptosis, ROS, Autophagy

Highlights

-

•

Anti-SVCV activities of 12 natural compounds and 7 common antiviral agents were investigated.

-

•

ARG showed the highest inhibition on SVCV replication.

-

•

ARG could inhibit reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis induced by SVCV.

-

•

Autophagy induced by SVCV, which is required for virus replication, was inhibited by ARG treatment.

-

•

ARG has the potential to work as an agent for protecting economical fishes against SVCV.

1. Introduction

Spring viraemia of carp virus (SVCV), belonging to the family Rhabdoviridae, is responsible for the highly lethal spring viraemia of carp (SVC) and is a grave viral threat that continues to infect cyprinids, especially common carp (Cyprinus carpio) (Shao et al., 2015). Until now, SVCV has widely spread to Asia, Europe, America and Russia, and this implies that SVCV infection is rapidly expanding along with the increasingly frequent national and international trade (Goodwin, 2002, Dikkeboom et al., 2004, Warg et al., 2007, Miller et al., 2007, Phelps et al., 2012). Notably, in addition to spread among fish, SVCV infection can also be spread through parasitic and fomites invertebrates (Fijian, 1984, Ahne et al., 2002). Thus, it is difficult to eradicate the virus from affected ponds, and the only effective treatment to block SVCV infection is elimination and sanitation of all infected aquatic life (Ahne et al., 2002, Shao et al., 2015, Ashraf et al., 2016).

Effective treatment of fish viral disease is too a large extent still elusive in aquaculture and limited to cases for which vaccines against viral infectious agents have been developed (Ashraf et al., 2016). Traditionally, DNA or oral vaccine is an important way to resolve viral diseases in aquaculture (Zhu et al., 2014, Emmenegger and Kurath, 2008, Cui et al., 2015). However, their use in aquaculture is still restricted due to the handling stress on fish, as well as high labour and production costs (Life, 2008). Moreover, RNA-mediated interference has also been reported to inhibit SVCV infection in vitro (Gotesman et al., 2015), but it takes a long time for this new technology to be put into production (Chen et al., 2015). Hence, there is no effective treatment for controlling SVCV in aquaculture up to now (Ashraf et al., 2016).

Recently, more and more natural compounds that are extracted from natural plants were found with antiviral activity. For example, saikosaponin A and C extracted from Radix bupleuri, and arctigenin (ARG) from Fructus Arctii showed antiviral activities against human coronavirus 229E and human immunodeficiency virus type-1, respectively (Cheng et al., 2006, Vlietinck et al., 1998); meanwhile, dioscin and angelicin isolated from Psoralea corylifolia inhibited the replication of adenovirus and gammaherpesviruses, separately (Liu et al., 2013, Cho et al., 2013). Remarkably, the application of natural compounds to control viral disease in aquaculture has attracted increasing attention due to their demonstrable efficacy and low environmental hazard. Chen et al. (2017) discovered that magnolol and honokiol extracted from Magnolia officinalis demonstrated a notably antiviral activity against grass carp reovirus. Additionally, ribavirin and other common antiviral agents have been reported to block a variety of virus infection (Butt and Kanwal, 2011, Yau and Yoshida, 2014, Debing et al., 2014), including aquatic animal virus (Yu et al., 2016, Zhu et al., 2015). However, antiviral agent against SVCV is still scarce until now (Shao et al., 2016). Hence, it is feasible to find anti-SVCV agents from natural compounds and common antiviral agents.

In an effort to discover anti-SVCV agents, in this study, the anti-SVCV activities of 12 natural compounds and 7 common antiviral agents, listed in Table 1 , were investigated using epithelioma papulosum cyprini (EPC) cells. ARG, the active compound, was chosen for further potential mechanism study, we analyzed the effect of ARG on i) the infectivity of SVCV; and ii) on the antiviral host response, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and autophagy. The results set foundation for the development of anti-SVCV agents and the further functional mechanism exploration of the antiviral agents.

Table 1.

List of all the compounds used in the study, their CAS numbers, purities, concentrations and effects on the expression of SVCV glycoprotein. Each value represents mean ± standard error.

| Category | Compound name | CAS number | Purity (%) | Concentration (mg/L) | Expression of SVCV glycoprotein (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural compounds | Angelicin | 523-50-2 | 98 | 40 | 84.96 ± 1.21 |

| Arctigenin | 7770-78-7 | 98 | 2 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | |

| Dioscin | 19057-60-4 | 98 | 50 | 89.53 ± 5.94 | |

| Gracillin | 19083-00-2 | 98 | 1.25 | 58.82 ± 1.28 | |

| Honokiol | 35354-74-6 | 98 | 5 | 61.36 ± 7.37 | |

| Kaempferol | 520-18-3 | 98 | 5 | 50.75 ± 4.37 | |

| Magnolol | 528-43-8 | 98 | 5 | 89.82 ± 6.81 | |

| Psoralidin | 18642-23-4 | 98 | 50 | 66.91 ± 8.09 | |

| Psoralen | 66-97-7 | 98 | 20 | 84.50 ± 2.43 | |

| Saikosaponin A | 20736-09-8 | 98 | 5 | 61.44 ± 4.35 | |

| Saikosaponin C | 20736-08-7 | 98 | 100 | 111.01 ± 5.72 | |

| Sanguinarine | 2447-54-3 | 98 | 0.625 | 64.94 ± 4.25 | |

| Common antiviral agents | Acyclovir | 59277-89-3 | 99 | 50 | 57.23 ± 1.57 |

| Amantadine | 768-94-5 | 99 | 20 | 51.39 ± 0.82 | |

| Cytarabine | 147-94-4 | 98 | 25 | 58.11 ± 3.69 | |

| Ganciclovir | 82410-32-0 | 98 | 50 | 113.72 ± 3.53 | |

| Moroxydine hydrochloride | 3160-91-6 | 99 | 100 | 90.02 ± 1.81 | |

| Ribavirin | 36791-04-5 | 98 | 100 | 77.08 ± 1.70 | |

| Vidarabine | 24356-66-9 | 99 | 12.5 | 116.64 ± 2.49 |

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines, virus and compounds

Epithelioma papulosum cyprinid (EPC) cells (kindly provided by Prof. Ling-bing Zeng in Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute, Wuhan, Hubei, China) were cultured at 25 ± 0.5 °C in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, and maintained in Medium 199 (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ZETA LIFE, USA). SVCV (strain 0504) was kindly provided by Professor Qiang Li in Key Laboratory of Mariculture, Agriculture Ministry, PRC, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian, China. ARG and seven common antiviral agents were purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Kaempferol, saikosaponin A and saikosaponin C were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Llc. Gracillin, honokiol, magnolol, psoralen and sanguinarine were purchased from Nanjing spring & autumn biological engineering Co., Ltd. Dioscin, psoralidin and angelicin were extracted from Dioscorea collettii and Psoralea corylifolia based on the previous studies (Liu et al., 2015a, Song et al., 2015). The CAS numbers and purities of all the 19 compounds were shown in Table 1.

2.2. Detection of mRNA expression by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.2.1. Anti-SVCV activity assay of 19 compounds

As shown in Fig. S1, each of the 19 compounds was diluted to six concentrations and the cell viability was measured using trypan blue exclusion dye staining test. Under the premise that cell viability was > 80%, the highest concentrations used in this test were chosen as the concentrations for anti-SVCV activity assay.

To detect SVCV by qRT-PCR, EPC cells were seeded into 12-well culture plates for 24 h, and then infected with 100TCID50 SVCV for 2 h. After that, the medium was replaced with cell maintenance medium (medium 199 supplemented with 5% FBS) containing 19 compounds and incubated at 25 ± 0.5 °C for 48 h. Afterwards, viral RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR were performed as described with some modifications (Yu et al., 2016). The primers for SVCV glycoprotein and EPC cell β-actin were shown in Table S1. The expression of SVCV glycoprotein related to β-actin gene was measured. The cycling conditions were 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min.

2.2.2. Dose effect of ARG on SVCV replication

ARG was diluted to seven concentrations (1.60, 1.00, 0.63, 0.40, 0.25, 0.16 and 0.10 mg/L) using cell maintenance medium. DMSO at 0.08‰ was served as vehicle control. Virus infection and ARG treatment were in the method of Section 2.2.1. The expression of SVCV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein related to β-actin gene was measured. The primers for SVCV nucleoprotein were also shown in Table S1. The cycling conditions were 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min. The inhibition of cell proliferation after treatment of ARG for 48 h was measured using cell counting kit-8 assay (CCK-8, Beyotime, China) at 450 nm following the manufacturer's protocol.

2.3. Virus titration and cytopathic effects (CPE) reduction assays of ARG

Virus multiplication and titration assays were performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2015b).

The protection efficiency of ARG on the viability of EPC cells was measured using CCK-8 Kit. EPC cells were cultured in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) for 24 h. Then, the medium was replaced with 100 μL cell maintenance medium containing 100TCID50 SVCV. After 2 h of infection, the medium was replaced again with maintenance medium containing 1.60 mg/L ARG. Each sample was directly observed and photographed under an inverted microscope. EPC cells viability was measured after 48 and 72 h incubation using a fluorescence plate reader (TECAN infinite M200, TECAN), respectively.

2.4. Cellular apoptosis and caspase activity assays

Cells seeded in 6-well culture plates were infected with 100TCID50 SVCV for 2 h, after that the medium was replaced with new maintenance medium containing 1.6 mg/L ARG and incubated for 48 and 72 h. Apoptosis assay was performed using Annexin V/PI (Vazyme, China) staining (Zhu et al., 2016). The activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9 was measured using caspase assay kits (Beyotime, China) (Zhu et al., 2015).

2.5. Cell nuclear damage assay and ultrastructural observation

For cell nuclear damage assay, cells were seeded on the sterile sheet glass in 12-well culture plates for 24 h and were infected with 100 TCID50 SVCV for 2 h. Later the medium was replaced with new medium containing ARG (1.6 mg/L). After 48 and 72 h of incubation, the cells were washed with 0.1 M PBS for three times and subsequently dyed with 1 mg/L DAPI, 5 mg/mL Dil. Fluorescence was observed with an upright fluorescence microscopy (Leica-DM5000, Germany).

For ultrastructural observation, cells were infected with 100TCID50 SVCV for 2 h, and then the medium was replaced with new maintenance medium containing 1.6 mg/L ARG. The SVCV-infected and drug-treated EPC cells were collected at 48 and 72 h post infection (p.i.), and fixed with 2.5% glutaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. According to the study of Shen et al. (2014), EPC cells were observed by a field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, S-4800, Hitachi, Japan) at 10 kV.

2.6. Fluorescence assay of ROS

ROS in both SVCV-infected and ARG-treated EPC cells was observed through the 2′,7′–dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) oxidant-sensitive probe to assess the intracellular ROS levels following the instructions of ROS kit (Beyotime, China). The product DCF was observed with an upright fluorescence microscopy (Leica-DM5000, Germany) and measured with a fluorescence plate reader (TECAN infinite M200, TECAN).

2.7. Autophagy detection

EPC cells were harvested and detected by autophagy assay kit (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) under the manufacturer's instructions. After incubation, the medium was removed and 100 μL of the autophagosome detection reagent working solution was added to each well. EPC cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. The fluorescence intensity (λex = 360/λem = 520 nm) was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (TECAN infinite M200, TECAN).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by probit analysis which was used for calculating the inhibitory concentration at half-maximal activity (IC50) of the compound at the 95% confidence interval by using the SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. an IBM Company). Drug response curves were represented by a logistic sigmoidal function with a maximal effect level (Amax) and a Hill coefficient representing the sigmoidal transition, which was performed with Origin 8.1. Values were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA), using one-way ANOVA after normalization to determine significance. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, **, p < 0.01 and *, p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Anti-SVCV activities of the 19 compounds

The anti-SVCV activities of the 12 natural compounds and 7 common antiviral agents were presented in Table 1, respectively. Compounds were considered active if the expression of SVCV glycoprotein was lower than 50%. Regrettably, there was no effective anti-SVCV agent in the seven common antiviral agents. Surprisingly, among the 12 natural compounds tested, ARG with an inhibitory percentage of > 90% proved to be the most effective.

3.2. Antiviral activity of ARG against SVCV

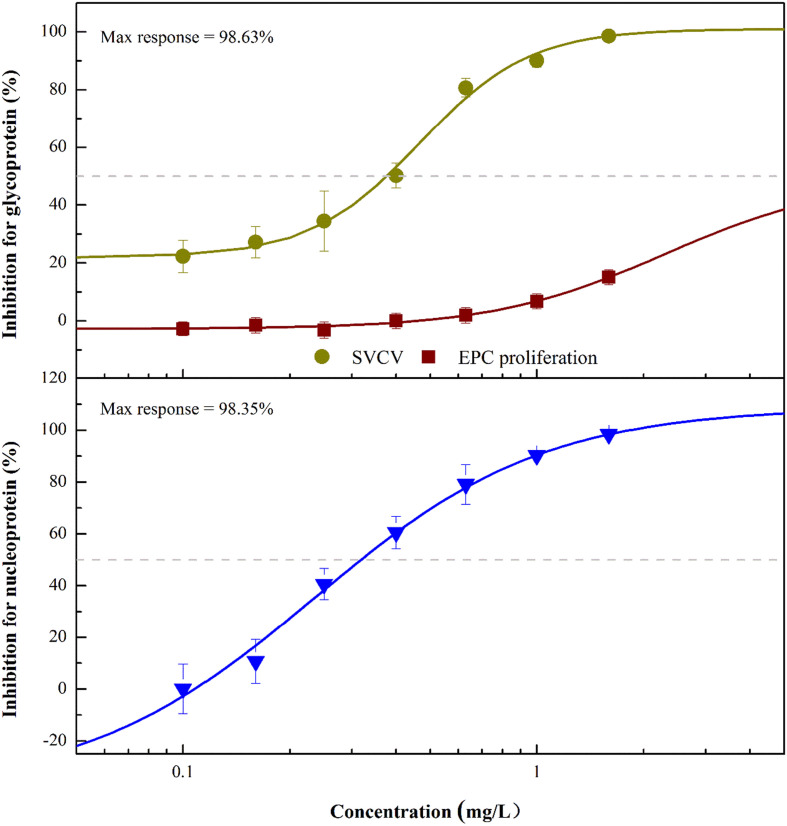

Due to the high antiviral activity of ARG against SVCV, the dose effect of ARG on SVCV replication was investigated. As shown in Fig. 1 , ARG had a concentration-dependent inhibition on the expressions of SVCV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein. The 48 h IC50 of ARG on SVCV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein were 0.29 (0.22–0.39) and 0.35 (0.29–0.41) mg/L, respectively. Additionally, the maximum responses of the inhibition were 98.63% and 98.35% for glycoprotein and nucleoprotein under the condition of 1.6 mg/L ARG. It should be noted that 1.6 mg/L ARG had no significant influence on the viability of EPC cells.

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory seven-point dose-response curves for antiviral activities of arctigenin (ARG) in EPC cells. The percent cytotoxicity of ARG on the uninfected host cells was shown in wine, and the percent inhibition of ARG in the SVCV of glycoprotein and nucleoprotein expression assay was shown in dark yellow and blue, respectively. The maximum percent inhibition observed (Max response) of SVCV were indicated. Data were shown as mean ± SD. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

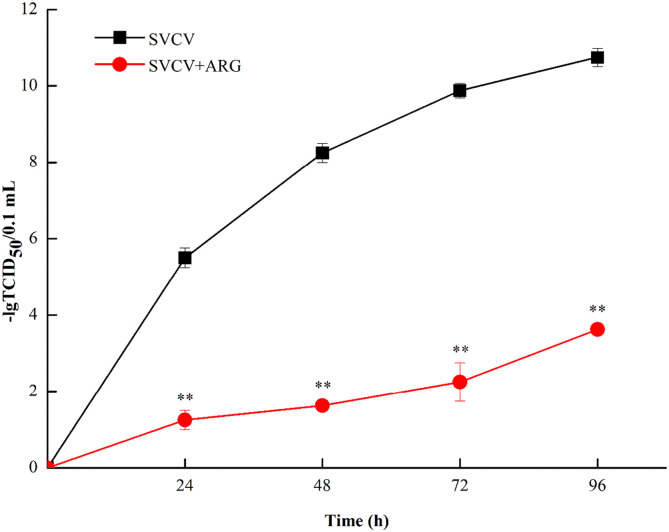

In addition, significant inhibition of SVCV was shown in ARG-treated EPC cells in the measurement of the viral titer (Fig. 2 ). The results indicated that SVCV titers were 105.5 (24 h p.i.), 108.3 (48 h p.i.), 109.9 (72 h p.i.) and 1010.8 (96 h p.i.) TCID50/0.1 mL. By contrast, the virus titers were much lower in the presence of 1.6 mg/L ARG, with SVCV titers were 101.3 (24 h p.i.), 101.6 (48 h p.i.), 102.3 (72 h p.i.) and 103.7 (96 h p.i.) TCID50/0.1 mL.

Fig. 2.

ARG reduced the titers of SVCV in EPC cells. EPC cells were infected with SVCV with (shown in red) or without 1.6 mg/L ARG (shown in black). Viral titers were determined by TCID50 at the indicated times. Error bars indicate the SD. Results were from a minimum of three replicates. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

To further confirm the antiviral activity of ARG against SVCV, the protective effect of ARG on the viability of EPC cells was measured. The result in Fig. S2 showed that CPE appeared in EPC cells after SVCV infection for 48 h and CPE-induced cell death occurred at 72 h. Importantly, ARG blocked SVCV-induced CPE and cell death, and could maintain the normal growth of EPC cells. The cell viabilities of ARG-treated EPC cells were 89.7 ± 2.5% and 79.4 ± 1.8% when the cell viabilities of SVCV-treated group were 40.1 ± 2.2% and 30.2 ± 3.3% at 48 and 72 h p.i., respectively.

3.3. ARG could inhibit the apoptosis induced by SVCV

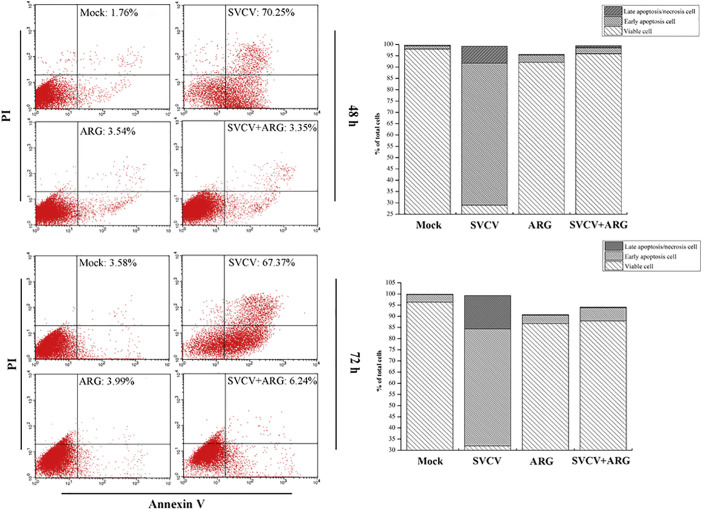

Apoptosis plays an important role in normal development and regulation of various physiological processes (Nikoletopoulou et al., 2013). Previous study indicated that SVCV induced apoptosis in EPC cells (Björklund et al., 1997, Yuan et al., 2014). In the current study, Annexin V/PI was used for evaluating the anti-apoptotic effect of ARG by measuring the percentage of viable cells and apoptotic cells. As shown in Fig. 3 , SVCV infection caused significant apoptosis in EPC cells, with a large percentage (62.74%) of EPC cells were undergoing early apoptosis at 48 h p.i. (Fig. 3A) and 14.98% of cells were in the condition of late apoptosis/necrosis at 72 h p.i. (Fig. 3B). Specially, ARG exhibited a positive inhibition on the apoptosis induced by SVCV, with the percentage of viable cells were 95.83% and 87.94% after 48 and 72 h p.i. These results suggested that treatment with ARG could block the occur of apoptosis in SVCV-infected cells.

Fig. 3.

ARG inhibited SVCV-induced apoptosis in EPC cells. The percentage of viable, early apoptosis and late apoptosis/necrosis cells was assessed by Annexin V/PI staining at 48 (A) and 72 (B) h post-infection.

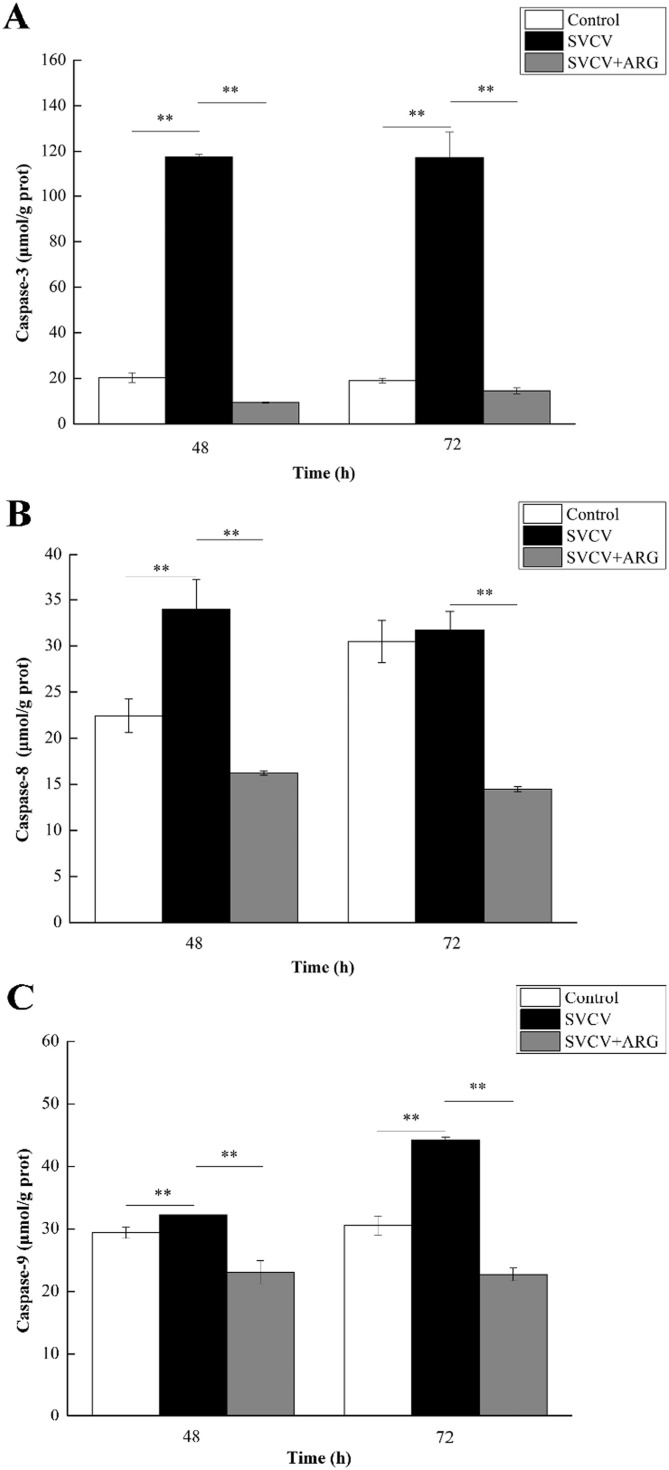

To explore the potential mechanism of SVCV induced apoptosis and protective response of ARG, the activity of caspase 3, 8 and 9 was evaluated at 48 and 72 h. As shown in Fig. 4 B, a significant increase of caspase-8 was observed after infection with SVCV for 48 h. In addition, a significant increase was also observed in caspase-3 and -9 after infection with SVCV for 48 and 72 h (Fig. 4A). Instead, a significant decrease of caspases was found in response to 1.6 mg/L ARG versus the SVCV treatments, decreasing 108.17–102.78 μmol/g prot (48–72 h p.i.) for caspase-3, 17.76–17.26 μmol/g prot for caspase-8 and 9.15–21.54 μmol/g prot for caspase-9, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Induction of caspase-3 (A), − 8 (B) and − 9 (C) activities in EPC cells after exposure to various treatment of 100TCID50 SVCV and 1.6 mg/L ARG for 48 and 72 h. Value represents the mean ± SD of three replicate samples. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

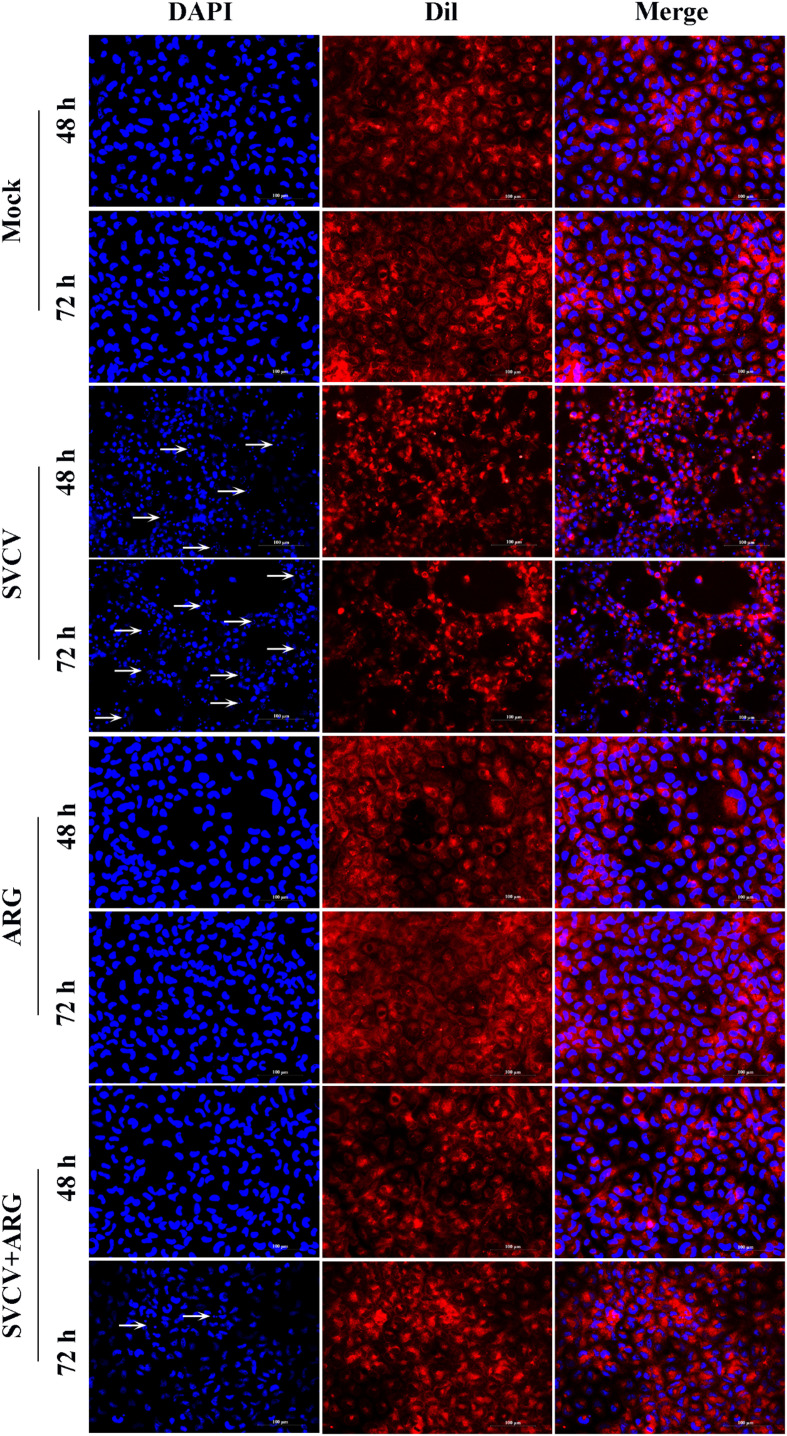

3.4. ARG had morphologically protective effect on EPC cells

In accordance with the results of flow cytometry, fluorescence observation of EPC cells stained by Dil/DAPI also confirmed the anti-apoptotic effect of ARG. As shown in Fig. 5 , SVCV-infected cells were found with typical apoptotic features, such as cellular morphology disappearance, cytoplasmic degradation and nuclear fragmentation. Due to the anti-apoptotic effect of ARG, the apoptotic features were weakened in ARG treatments where the quantity of apoptosis body was reduced sharply and the nucleus remained in a normal spindle shape. It should be noted that ARG weakened SVCV-induced apoptosis, which further confirmed the inhibition effect of ARG on SVCV.

Fig. 5.

ARG reduced the quantity of apoptosis body in EPC cells. EPC cells in 12-well plate were treated in the presence of 1.6 mg/L ARG with SVCV infection (100TCID50). The cells were collected after 48 and 72 h post infection and apoptosis body was detected as arrows indicating.

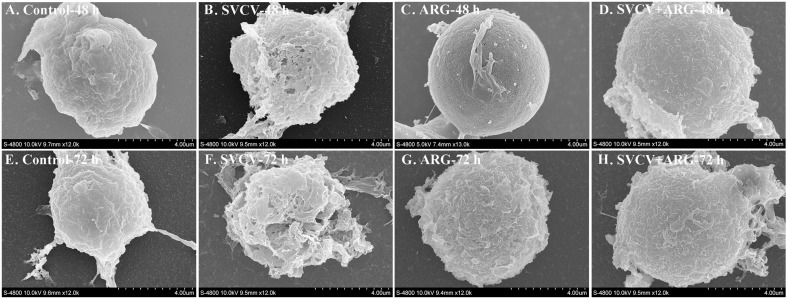

Additionally, scanning electron micrographs of the EPC cells reflected that normal cells were round, plump and intact, and retained spherical shape (Fig. 6 A and E). By contrast, after 48 and 72 h infection with SVCV, EPC cells were significantly shrunk and appeared typical apoptotic features including cell shrinkage, volume reduction and cell blebbing (Fig. 6B and F). Through inhibiting SVCV replication, the SVCV-induced morphological changes were not observed in ARG-treated EPC cells (Fig. 6D and H). It should be noted that ARG had morphologically protective effect on EPC cells, which further confirmed that ARG was highly effective against SVCV infection.

Fig. 6.

Scanning electron microscopy image showed the morphological effect of SVCV infection and antiviral activity of 1.6 mg/L ARG after 48 (A–D) and 72 (E–H) h.

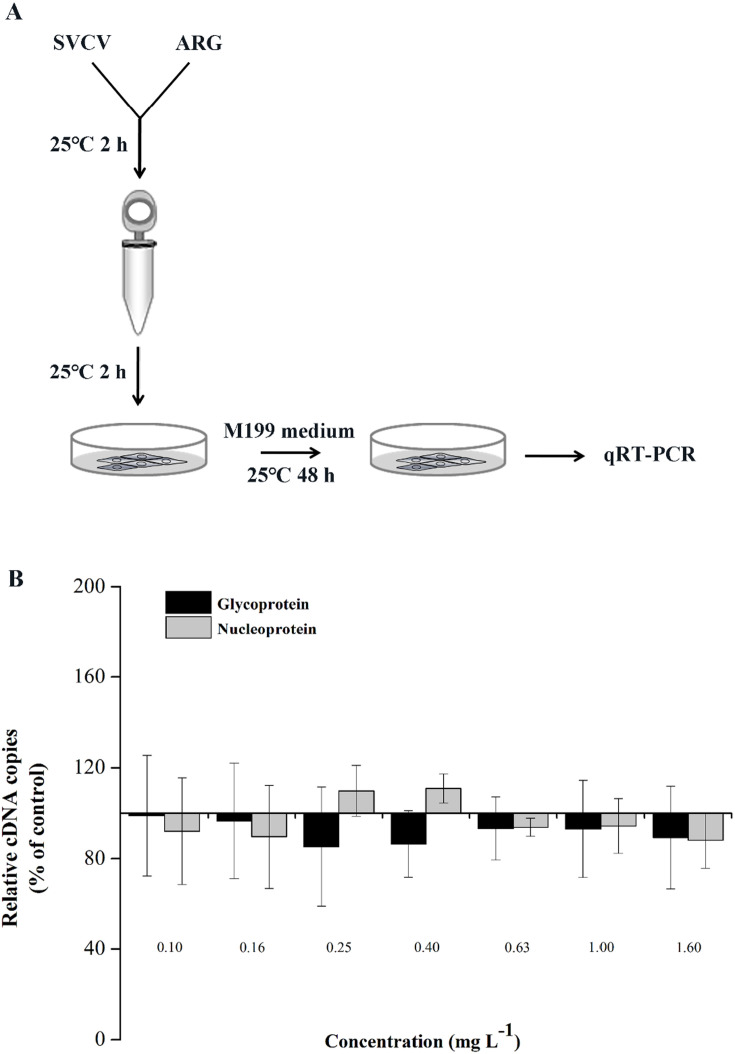

3.5. ARG had no effect on the infectivity of SVCV

To better understand the mechanism by which ARG inhibit SVCV replication, we investigated the effect of ARG on SVCV infectivity. To interrogate if ARG could affect the infectivity of SVCV, 100TCID50 SVCV were incubated with 0.10 to 1.60 mg/L ARG at 25 ± 0.5 °C in cell maintenance medium for 2 h, then this mixed solution was added to EPC cells in 12-well culture plates. After incubation for 2 h, the medium was replaced with new maintenance medium. After 48 h of incubation, the remaining infectivity of SVCV was analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7B, no significant effect was observed on SVCV infectivity exposed to all the concentrations of ARG.

Fig. 7.

The infectivity of SVCV was not affected by ARG. (A) Workflow of the experimental design followed in (B). Briefly, 100TCID50 SVCV were incubated with 0.10 to 1.60 mg/L ARG at 25 ± 0.5 °C in cell maintenance medium for 2 h, then the medium containing SVCV and ARG was added to EPC cells growing in monolayer at 90% of confluence and incubated for 2 h. Afterwards, the cells were washed with PBS for three times and new maintenance medium was added to cells. After incubation for 48 h, the cells were collected and were analyzed using qRT-PCR. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of glycoprotein and nucleoprotein encoding gene. (C) Workflow representing the experimental design for (D). SVCV stock (100TCID50) was treated with ARG (1.6 mg/L) or DMSO control for 4 h at 25 ± 0.5 °C. Subsequently, samples were ultracentrifuged at 33000 g for 1.5 h at 4 °C and the pellets were resuspended with maintenance medium. Then EPC cells were infected with above treated virus, the remaining infectivity were detected after 48 h infection using qRT-PCR. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of glycoprotein and nucleoprotein encoding gene. Bars represent mean ± SD of triplicate readings from one sample and the data are representative of two independent experiments.

To further confirm that ARG had no effect on the infectivity of SVCV indeed, we incubated SVCV with 1.6 mg/L ARG for 4 h in vitro and recovered the virion particles by ultracentrifugation before inoculation of cultures (Fig. 7C). The results in Fig. 7D showed that incubation of the virus with ARG did not significantly reduce its infectivity in EPC cells.

3.6. ARG did not induce ROS generation in EPC cells

Our pervious study has shown that SVCV infection induced ROS generation and ROS played an antiviral role in SVCV infection (Liu et al., 2017). Hence, we decided to investigate if the antiviral role of ARG in SVCV replication was the result of inducing ROS generation. After 2 h of SVCV infection, the medium was replaced with 1.6 mg/L ARG and incubated at 25 ± 0.5 °C for 48 h (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8B and C, ARG did not induce ROS generation, and in contrast, ROS were slightly inhibited by treated with ARG alone. In addition, ROS induced by SVCV was inhibited by ARG treatment in EPC cells, which confirmed the antiviral activity of ARG against SVCV. Altogether, the inhibition of ARG on SVCV was not via inducing ROS generation.

Fig. 8.

ARG could not induce ROS generation but inhibited SVCV-induced ROS generation in EPC cells. (A) Workflow representing the experimental design followed in (B) and (C). Briefly, EPC cells were infected with SVCV for 2 h, then the medium was replaced with new medium containing 1.6 mg/L ARG. After incubation for 48 h, the cells were stained with 2′,7′–dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) oxidant-sensitive probe for ROS detection. (B) Fluorescence observation of ROS in EPC cells treated with or without ARG. (C) The value of ROS fluorescence in EPC cells treated with or without ARG. Value represents the mean ± SD of three replicate samples. Significance between control and exposure groups are indicated by **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

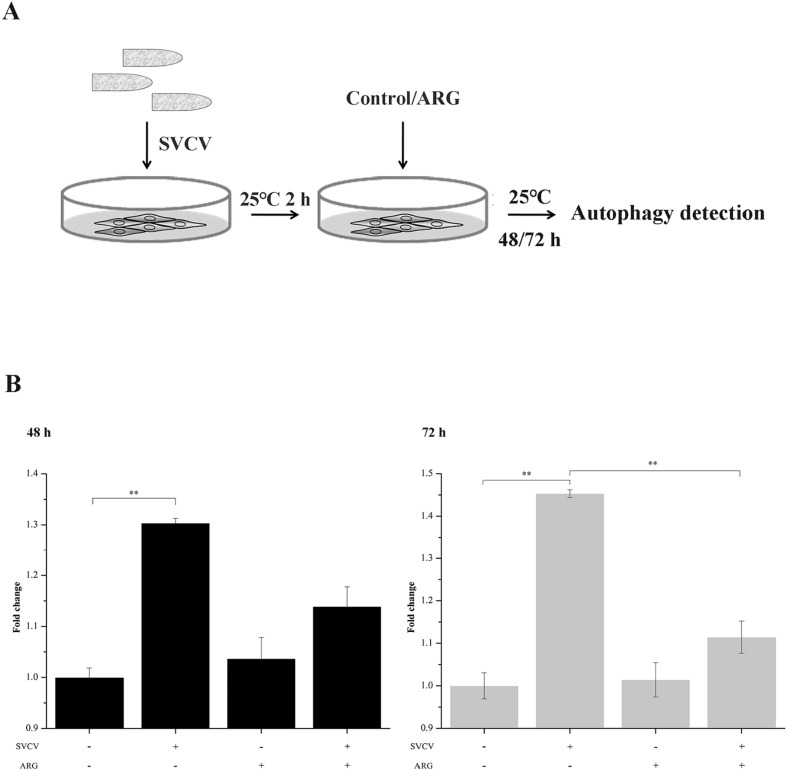

3.7. ARG inhibited SVCV-induced autophagy which is required for necessary viral replication

Since autophagy was induced by SVCV for necessary viral replication in EPC cells (Liu et al., 2015b), we further investigated the effect of ARG on autophagy. EPC cells were infected with SVCV for 2 h, afterwards, the medium was replaced with new medium containing 1.6 mg/L ARG and incubated for 48 and 72 h at 25 ± 0.5 °C (Fig. 9A). As expected, SVCV induced autophagy in EPC cells (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, the autophagy induced by SVCV was significantly inhibited by ARG although ARG alone slightly enhanced the host autophagic response (Fig. 9B). Taken together, these results suggested that the inhibition of ARG on SVCV infection is, at least in part, through inhibiting SVCV-induced autophagy.

Fig. 9.

Autophagy induced by SVCV was inhibited by ARG. (A) Workflow representing the experimental design followed in (B). EPC cells were infected with SVCV for 2 h and subsequently treated with new medium containing 1.6 mg/L ARG. After 48 h incubation, cells were stained with autophagosome detection reagent. (B) The value of autophagy fluorescence in EPC cells treated with or without ARG. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and each value represented mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Outbreaks of SVC usually caused mass mortality and brought substantial economic loss to aquaculture industry, for example, the annual loss of carp was estimated to be as high as 4000 metric tons in Europe (Teng et al., 2007, Walker and Winton, 2010). Unfortunately, no approved agent could be used for controlling SVCV currently. The present study for the first time explored the antiviral activity of 12 natural compounds and 7 common antiviral agents against SVCV, and found that ARG had the highest inhibition on SVCV replication. Further study focusing on the antiviral mechanism of ARG demonstrated that ARG did not affect the infectivity of SVCV and did not induce ROS generation. In contrast, ARG inhibited the autophagy induced by SVCV, which is necessary for SVCV replication (Liu et al., 2015b).

Apoptosis can be triggered through two general mechanisms: from within (intrinsic) or from outside (extrinsic) the cell (Best, 2008, Clarke and Tyler, 2009). SVCV infection had been demonstrated to induce apoptosis through TNF mediated extrinsic pathway and the mitochondrial pathway (Yuan et al., 2014). In accordance with pervious study (Yuan et al., 2014), caspase-3, -8 and -9 activities were significantly up-regulated in this study. Importantly, ARG treatment inhibited apoptosis and recovered caspase-3, -8 and -9 activities. This indicated that the intrinsic and extrinsic pathway were both not activated because of the antiviral activity of ARG. Additionally, apoptosis plays a crucial role in host defense against viral infections (Chattopadhyay et al., 2016). For example, soft-shelled turtle iridovirus and largemouth bass virus induced the occurrence of apoptosis which in turn defensed virus infection in some extent (Huang et al., 2014). Apoptosis occurred during SVCV infection and ARG treatment could inhibited apoptosis. This indicated that the host cells did not need to induce apoptosis to combat SVCV infection because of the antiviral effect of ARG.

The full genome of SVCV, one negative-sense single-stranded RNA virus, contains 5 segments encoding 5 proteins: Glycoprotein, Nucleoprotein, Matrix protein, Phosphoprotein and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Glycoprotein is on the surface of the virus and is the most important viral antigenic protein that determines the infectivity and serological properties (Johnson et al., 1999). Because ARG was highly effective to SVCV, we first speculated if ARG could damage the structure of glycoprotein and affect SVCV infectivity. However, we found that ARG had no effect on SVCV infectivity. This indicated that the structure of glycoprotein cannot be damaged by ARG directly in vitro. Linked with the study of Hayashi et al. (2010) which found the targets of ARG are the early events of influence virus type A replication after penetration into cells, we speculated that the antiviral effect of ARG was most likely due to inhibition effect on one or multiple intracellular replication events of SVCV.

ROS played a broad role in host defense against microbial invasion (Narayanan et al., 2014), including SVCV. Our pervious study had shown that ROS generation could suppress SVCV replication (Liu et al., 2017). Thereby, we investigated whether ARG inhibited SVCV replication through activating ROS generation. However, ARG caused a slight reduction of ROS rather than induced ROS generation in EPC cells, which indicated that the antiviral activity of ARG was not due to ROS generation. On the other hand, oxidative stress was confirmed as a mediator of apoptosis in virus-infected cells (Li et al., 2016). In this study, we found that SVCV-induced ROS production was inhibited by ARG treatment, which might be related to the anti-apoptosis effect of ARG. In addition, ROS was known to trigger the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis mediated by caspase-9, in accordance with this, the activated caspase-9 activity was recovered by ARG treatment.

Autophagy has diverse physiological functions, such as routine organelle and protein turnover, cellular adaption to stress, and innate immunity against viruses (Orvedahl and Levine, 2008). Some viruses inhibited this pathway for their survival, while others enhanced to benefit this pathway (Sir and Ou, 2010). SVCV had been found inducing autophagy in EPC cells, which is required for necessary viral replication (Liu et al., 2015b). Here, we found that the autophagy induced by SVCV was inhibited by ARG treatment. This inhibition on autophagy might be caused by the following two reasons: 1) ARG had a direct effect on autophagy and then inhibited SVCV replication; 2) ARG inhibited SVCV-induced autophagy via suppressing SVCV first. By treating EPC cells with ARG alone, we found that ARG did not inhibit autophagy directly, and thus, its inhibition on SVCV-induced autophagy was mainly caused by the second reason. Since SVCV glycoprotein, rather than viral replication, activates autophagy pathway (Liu et al., 2015b), it should be important to emphasize that ARG had no effect on SVCV infectivity, which implied ARG could not damage the structure of SVCV glycoprotein. These also indicated that ARG could not inhibit SVCV-induced autophagy directly. Although autophagy was not the primary molecular target of ARG, the inhibition of ARG on SVCV-induced autophagy occurred indeed, and this could be beneficial to the host cell to combat virus infection in some extent.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that ARG could inhibit SVCV replication and block SVCV-induced ROS generation and apoptosis. Mechanistically, ARG had no effect on SVCV infectivity and did not induce ROS generation. However, ARG suppressed the autophagy induced by SVCV. Taken together, ARG is regarded as a compound with high anti-SVCV activity and is expected to be a therapeutic agent against SVCV infection. Our further work will pay attention to the antiviral activity of ARG in vivo.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

The toxicity of all the 19 compounds on EPC cells. (A) The toxicity of 12 natural compounds to EPC cells. (B) The toxicity of 9 common antiviral agents to EPC cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Morphological effect and cell viability of ARG against SVCV in EPC cells. Each value was represented as mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Ling-bing Zeng in Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute for providing EPC cells and Professor Qiang Li in Key Laboratory of Mariculture, Agriculture Ministry for providing SVCV strains. This work was supported by the Shaanxi Science and Technology Co-ordination Innovation Engineering Project (2015KTTSNY01-02) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2452017078).

Reference

- Ahne W., Bjorklund H., Essbauer S., Fijan N., Kurath G., Winton J. Spring viremia of carp (SVC) Dis. Aquat. Org. 2002;52:261–272. doi: 10.3354/dao052261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf U., Lu Y., Lin L., Yuan J., Wang M., Liu X. Spring viraemia of carp virus: recent advances. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:1037–1051. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best S.M. Viral subversion of apoptotic enzymes: escape from death row. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:171–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund H.V., Johansson T.R., Rinne A. Rhabdovirus-induced apoptosis in a fish cell line is inhibited by a human endogenous acid cysteine proteinase inhibitor. J. Virol. 1997;71:5658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5658-5662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt A.A., Kanwal F. Boceprevir and telaprevir in the management of hepatitis C virus infected patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. Cir. 2011;774:1–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S., Kuzmanovic T., Ying Z., Wetzel J.L., Sen G.C. Ubiquitination of the transcription factor IRF-3 activates RIPA, the apoptotic pathway that protects mice from viral pathogenesis. Immunity. 2016;44:1151. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Li W., Jin E., He Q., Yan W., Yang H., Gong S., Guo Y., Fu S., Chen X., Ye S., Qian Y. The antiviral activity of arctigenin in traditional Chinese medicine on porcine circovirus type 2. Res. Vet. Sci. 2015;106:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Hu Y., Shan L., Yu X., Hao K., Wang G.X. Magnolol and honokiol from Magnolia officinalis enhanced antiviral immune responses against grass carp reovirus in Ctenopharyngodon idella kidney cells. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;63:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P.W., Ng L.T., Chiang L.C., Lin C.C. Antiviral effects of saikosaponins on human coronavirus 229E in vitro. Chin. Exp. Pharmacol. P. 2006;33:612–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H.-J., Jeong S.-G., Park J.-E., Han J.-A., Kang H.-R., Lee D., Song M.J. Antiviral activity of angelicin against gammaherpesviruses. Antivir. Res. 2013;100:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P., Tyler K.L. Apoptosis in animal models of virus-induced disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:144–155. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.C., Guan X.T., Liu Z.M., Tian C.Y., Xu Y.G. Recombinant lactobacillus expressing G protein of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) combined with ORF81 protein of koi herpesvirus (KHV): a promising way to induce protective immunity against SVCV and KHV infection in cyprinid fish via oral vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33:3092–3099. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debing Y., Emerson S.U., Wang Y., Pan Q., Balzarini J., Dallmeier K., Neyts J. Ribavirin inhibits in vitro hepatitis E virus replication through depletion of cellular GTP pools and is moderately synergistic with alpha interferon. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:267–273. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01795-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikkeboom A.L., Radi C., Toohey-Kurth K., Marcquenski S., Engel M., Goodwin A.E., Way K., Stone D.M., Longshaw C. First report of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) in wild common carp in North America. J. Aquat. Anim. Health. 2004;16:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Emmenegger E.J., Kurath G. DNA vaccine protects ornamental koi (Cyprinus carpio koi) against North American spring viremia of carp virus. Vaccine. 2008;26:6415–6421. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijian N. Vaccination of fish in European pond culture: prospects and constraints. Symp. Biol. Hung. 1984;23:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin A.E. First report of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) in North America. J. Aquat. Anim. Health. 2002;14:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gotesman M., Soliman H., Besch R., El-Matbouli M. Inhibition of spring viraemia of carp virus replication in an Epithelioma papulosum cyprini cell line by RNAi. J. Fish Dis. 2015;38:197–207. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Narutaki K., Nagaoka Y., Hayashi T., Uesato S. Therapeutic effect of arctiin and arctigenin in immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice infected with influenza A virus. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010;33:1199–1205. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Wang W., Huang Y., Xu L., Qin Q. Involvement of the PI3K and ERK signaling pathways in largemouth bass virus-induced apoptosis and viral replication. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;41:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M., Maxwell J.P., Leong J. Molecular characterization of the glycoproteins from two warm water rhabdoviruses: snakehead rhabdovirus (SHRV) and rhabdovirus of penaeid shrimp (RPS)/spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) Virus Res. 1999;64:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Xu X., Leng X., He M., Wang J., Cheng S., Wu H. Roles of reactive oxygen species in cell signaling pathways and immune responses to viral infections. Arch. Virol. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Life M. Development of an oral vaccine for immunisation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) against viral haemorrhagic septicaemia. Vaccine. 2008;26:837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wang Y., Wu C., Pei R., Song J., Chen S., Chen X. Dioscin's antiviral effect in vitro. Virus Res. 2013;172:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Shen Y.F., Liu G.L., Fei L., Liu X.Y., Hu K., Yang X.L., Wang G.X. Inhibition of dioscin on Saprolegnia in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015;362 doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhu B., Wu S., Lin L., Liu G., Zhou Y., Wang W., Asim M., Yuan J., Li L., Wang M., Lu Y., Wang H., Cao J., Liu X. Spring viraemia of carp virus induces autophagy for necessary viral replication. Cell. Microbiol. 2015;17:595–605. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Tu X., Shen Y.F., Chen W.C., Zhu B., Wang G.X. The replication of spring viraemia of carp virus can be regulated by reactive oxygen species and NF-κB pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;67:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller O., Fuller F.J., Gebreyes W.A., Lewbart G.A., Shchelkunov I.S., Shivappa R.B., Joiner C., Woolford G., Stone D.M., Dixon P.F., Raley M.E., Levine J.F. Phylogenetic analysis of spring virema of carp virus reveals distinct subgroups with common origins for recent isolates in North America and the UK. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2007;76:193–204. doi: 10.3354/dao076193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A., Amaya M., Voss K., Chung M., Benedict A. Reactive oxygen species activate NFkappaB (p65) and p53 and induce apoptosis in RVFV infected liver cells. Virology. 2014;449:270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoletopoulou V., Markaki M., Palikaras K., Tavernarakis N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy ☆. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:3448–3459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvedahl A., Levine B. Autophagy and viral neurovirulence. Cell. Microbiol. 2008;10:1747. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps N.B., Armien A.G., Mor S.K., Goyal S.M., Warg J.V., Bhagyam R., Monahan T. Spring viremia of carp virus in Minnehaha Creek, Minnesota. J. Aquat. Anim. Health. 2012;24:232–237. doi: 10.1080/08997659.2012.711267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L., Xiao Y., He Z.K., Gao L.Y. An N-targeting real-time PCR strategy for the accurate detection of spring viremia of carp virus. J. Virol. Methods. 2015;229:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J.H., Huang J., Guo Y., Li L.J., Liu X.Q., Chen X.X., Yuan J.F. Up-regulation of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) represses the replication of SVCV. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;58:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.F., Liu L., Gong Y.X., Zhu B., Liu G.L., Wang G.X. Potential toxic effect of trifloxystrobin on cellular microstructure, mRNA expression and antioxidant enzymes in Chlorella vulgaris. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014;37:1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sir D., Ou J.H. Autophagy in viral replication and pathogenesis. Mol. Cell. 2010;29:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0014-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K.G., Ling F., Huang A.G., Dong W.J., Liu G.L., Jiang C., Zhang Q., Wang G.X. In vitro and in vivo assessment of the effect of antiprotozoal compounds isolated from Psoralea corylifolia against Ichthyophthirius multifiliis in fish. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2015;5:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y., Liu H., Lv J.Q., Fan W.H., Zhang Q.Y., Qin Q.W. Characterization of complete genome sequence of the spring viremia of carp virus isolated from common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in China. Arch. Virol. 2007;152:1457–1465. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-0971-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlietinck A.J., De Bruyne T., Apers S., Pieters L.A. Plant-derived leading compounds for chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Planta Med. 1998;64:97–109. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker P.J., Winton J.R. Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp. Vet. Res. 2010;41:51. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warg J.V., Dikkeboom A.L., Goodwin A.E., Snekvik K., Whitney J. Comparison of multiple genes of spring viremia of carp viruses isolated in the United States. Virus Genes. 2007;35:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s11262-006-0042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau A.H.L., Yoshida E.M. Hepatitis C drugs: the end of the pegylated interferon era and the emergence of all-oral, interferon-free antiviral regimens: aconcise review. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;28:445. doi: 10.1155/2014/549624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.B., Chen X.H., Ling F., Hao K., Wang G.X., Zhu B. Moroxydine hydrochloride inhibits grass carp reovirus replication and suppresses apoptosis in Ctenopharyngodon idella kidney cells. Antivir. Res. 2016;131:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Yang Y., Nie H., Li L., Gu W., Lin L., Zou M., Liu X., Wang M., Gu Z. Transcriptome analysis of epithelioma papulosum cyprini cells after SVCV infection. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1(2014-10-25)):935. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Liu G.L., Gong Y.X., Ling F., Song L.S., Wang G.X. Single-walled carbon nanotubes as candidate recombinant subunit vaccine carrier for immunization of grass carp against grass carp reovirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;41:279–293. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Liu G.L., Ling F., Wang G.X. Carbon nanotube-based nanocarrier loaded with ribavirin against grass carp reovirus. Antivir. Res. 2015;118:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Zhu B., Huang A.G., Hu Y., Wang G.X., Ling F. Toxicological effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the uptake kinetics and mechanisms and the toxic responses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;318:650–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The toxicity of all the 19 compounds on EPC cells. (A) The toxicity of 12 natural compounds to EPC cells. (B) The toxicity of 9 common antiviral agents to EPC cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Morphological effect and cell viability of ARG against SVCV in EPC cells. Each value was represented as mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Primers used in this study.