Abstract

Oral administration of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) has attracted considerable attention as a means of controlling infectious diseases of bacterial and viral origin. Oral administration of IgY possesses many advantages compared with mammalian IgG including cost-effectiveness, convenience and high yield. This review presents an overview of the potential to use IgY immunotherapy for the prevention and treatment of terrestrial and aquatic animal diseases and speculates on the future of IgY technology. Included are a review of the potential application of IgY for the treatment of livestock diseases such as mastitis and diarrhea, poultry diseases such as Salmonella, Campylobacteriosis, infectious bursal disease and Newcastle disease, as well as aquatic diseases like shrimp white spot syndrome virus, Yersina ruckeri and Edwardsiella tarda. Some potential obstacles to the adoption of IgY technology are also discussed.

Keywords: Egg yolk immunoglobulin, IgY, Terrestrial, Aquatic, Disease control

1. Introduction

Antibiotics have been used in animal agriculture for growth promotion (sub-therapeutic doses), disease prevention (prophylactic doses) and for the treatment of infection for over 50 years (Turner et al., 2001 ). Years of research and practical experience have shown that antibiotic use significantly improves animal performance and health status (Cromwell, 2002). However, the use and misuse of in-feed antibiotics have led to problems with drug residues in animal products and increased bacterial resistance (Khachatourians, 1998). As a result, the sub-therapeutic use of antibiotics has been totally banned in European countries since January 2006 (Casewell et al., 2003) and other countries are seriously considering a similar ban. Therefore, alternatives to antibiotics are urgently needed.

A wide range of products have been tested as potential alternatives to antibiotics including organic and inorganic acids (Kim et al., 2005), oligosaccharides (Flickinger et al., 2003), probiotics (Kritas and Morrison, 2005, Taras et al., 2007), herbal extracts (Windisch et al., 2008) and antibodies (Cook, 2004). Among these, oral immunotherapy (passive immunization) with antibodies is a highly attractive and effective alternative approach due to its high specificity. Oral administration with antibodies derived from mammalian serum and colostrum and even monoclonal antibodies have been used successfully (Kuhlman et al., 1988). However, with this technique, it is prohibitively expensive to obtain the large amount of antibody required to prevent and treat disease.

Recently, chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin, referred to as immunoglobulin Y (IgY) has attracted considerable attention as a means to prevent and control disease as it possesses a large number of advantages compared with treatment with mammalian IgG including cost-effectiveness, convenience and high yield (Carlander et al., 2000). Under natural conditions, the serum IgY of laying hens is deposited in large quantities in the egg yolk in order to protect the developing embryo from potential pathogens (Janson et al., 1995). Thus, it is possible to immunize the hen against specific foreign pathogens thereby allowing the production of IgY with activity against these specific disease conditions.

Oral administration of specific IgY antibody has been shown to be effective against a variety of intestinal pathogens such as bovine and human rotaviruses, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), bovine coronavirus, Salmonella spp., Edwardsiella tarda, Yersinia ruckeri, Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas (Mine and Kovacs-Nolan, 2002). This review presents an overview of the potential to use immunotherapy with specific IgY for the prevention and treatment of terrestrial and aquatic animal diseases and speculates on the future of IgY technology.

2. Characteristics of chicken immunoglobulin Y (IgY)

2.1. Advantages of IgY

The use of chickens for the production of polyclonal antibodies provides many advantages over production methods using mammals (Table 1 ). The most significant advantage is that the collection of antibodies is non-invasive. In contrast to conventional methods where animals are often sacrificed in order to collect a sufficient amount of blood to obtain antibodies, production of antibodies in laying hens requires only the collection of eggs, and the high and long-lasting titers produced in chickens reduce the need for frequent booster injections. Another advantage is that due to the phylogenetic distance between chickens and mammals, chickens often more successfully produce antibodies against highly conserved mammalian proteins than do other mammals and require much less antigen to induce an efficient immune response.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of mammalian IgG and chicken IgY.

| Parameter | Mammalian IgG | Chicken IgY |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody sampling | Invasive | Non-invasive |

| Source of antibody | Blood serum | Egg yolk |

| Antibody amount | 200 mg IgG/bleed (40 ml blood) | 50–100 mg IgY/egg (300 eggs/year) |

| Frequency of collection | Every two weeks | Every day |

| Amount of antibody/year | 5200 mg | 22,500 mg |

| Amount of specific antibody | ~ 5% | 2–10% |

| Protein–A/G binding | Yes | No |

| Interference with mammalian IgG | Yes | No |

| Interference with rheumatoid factor | Yes | No |

| Activation of mammalian complement | Yes | No |

Adapted from Schade et al. (2005).

A hen can be considered as a small “factory” for antibody production. A hen usually lays about 300 eggs per year and the egg yolk (15 ml) contains 50–100 mg of IgY of which 2 to 10% are specific antibodies (Rose et al., 1974). Therefore, one immunized hen produces more than 22,500 mg of IgY per year which is equivalent to the production of 4.3 rabbits over the course of a year (Schade et al., 2005). The maintenance costs for keeping hens are also lower than those for mammals such as rabbits (Schade et al., 2005). Therefore, egg yolk provides a more hygienic, cost-efficient, convenient and rich source of antibodies compared with the traditional method of obtaining antibodies from mammalian serum. In contrast to antibiotics, the use of IgY is environmentally-friendly and elicits no undesirable side effects, disease resistance or toxic residues (Coleman, 1999).

2.2. Structure and function of chicken IgY

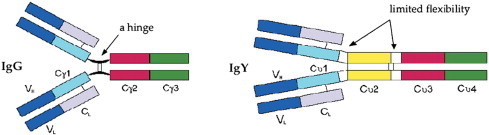

Initially, IgY antibodies were thought to be similar to IgG immunoglobulins, whereas they are now considered to be an evolutionary ancestor to mammalian IgG and IgE and also to IgA (Warr et al., 1995). Although chicken IgY is the functional equivalent of mammalian IgG, there are some profound differences in their structure. The general structure of the IgY molecule is the same as the IgG molecule with two heavy (H) chains and two light (L) chains but IgY has a molecular mass of 180 kDa which is larger than that of mammalian IgG (150 kDa) (Fig. 1 ). The molecular mass (67–70 kDa) of the H chain in IgY is larger than the H chain from mammals (50 kDa). The greater molecular mass of IgY is due to an increased number of heavy-chain constant domains and carbohydrate chains (Warr et al., 1995). IgG has 3 C regions (Cγ1–Cγ3), while IgY has 4 C regions (Cυ1–Cυ4) and the presence of one additional C region with its two corresponding carbohydrate chains logically results in a greater molecular mass of IgY compared with IgG.

Fig. 1.

Structure of IgG and IgY.

From Narat, 2003.

Other differences in structure include the fact that the hinged region of IgY is much less flexible compared with mammalian IgG. It has also been suggested that IgY is a more hydrophobic molecule than IgG (Davalos-Pantoja et al., 2000). Finally, IgY has an isoelectric point of pH 5.7–7.6, whereas that of IgG lies between 6.1 and 8.5 (Davalos-Pantoja et al., 2000, Sun et al., 2001).

Unlike mammalian IgG, IgY does not fix mammalian complement and does not interact with mammalian Fc and complement receptors (Carlander et al., 2000). As well, IgY does not bind to protein A, protein G or rheumatoid factor, so no false positives are obtained on immunoassay which is a problem with IgG-based mammalian assays (Davalos-Pantoja et al., 2000). These differences provide significant advantages to the application of IgY technology in many areas of research such as diagnostics (Erhard et al., 2000), antibiotic-alternative therapy (Carlander et al., 2000) and xenotransplantation (Fryer et al., 1999).

2.3. Storage stability of IgY

The stability of IgY during storage is reasonably good under specified conditions. IgY solutions may be stored at 4 °C for periods ranging from months to a few years provided 0.02% NaN3, 0.03% w/v thimerosal or 50 μg/ml gentamicin has been added to retard microbial growth (Schade et al., 2005). Dried IgY preparations were stored for five to ten years at 4 °C without significant loss of antibody activity and the preparations also retained activity for six months at room temperature and for one month at 37 °C (Larsson et al., 1993). While lyophilization minimizes bacterial growth and maintains better structural integrity of purified IgY, spray-drying is more economical (Yokoyama et al., 1992). Collectively, these unique biological attributes make IgY an effective natural food antimicrobial system and immunotherapeutic agent.

3. Mode of action

The exact mechanisms through which IgY counteracts pathogen activity have not been determined. However, several mechanisms have been proposed to express how specific IgY counteracts pathogen activity and these are outlined below.

-

(i)

Agglutination. Tsubokura et al. (1997) suggested that the inhibition of bacterial growth or colonization observed as a result of treatment with IgY can be the result of bacterial agglutination, causing a reduction in CFU rather than actual direct effects on individual bacteria. Although agglutination may be one mediator of growth inhibition, it is unlikely to be the most important mediator because cross-linking of bacteria is precluded by the steric hindrance of the two Fab arms of IgY (Gallagher and Voss, 1974).

-

(ii)

Adherence-blockade. Several in vitro studies have suggested that inhibition of adhesion is the dominant mechanism by which specific IgY counteracts pathogen activity (Jin et al., 1998, Lee et al., 2002). Jin et al. (1998) showed that IgY functions to prevent the adherence of E. coli K88 to the intestinal mucus of piglets. Particular components exposed on the Gram-negative bacteria surface such as outer membrane protein, lipopolysaccharide, fimbriae (or pili), and flagella, which are crucial factors for bacterial colonization, may be recognized and bound by related polyclonal antibody such as IgY (Sim et al., 2000). This binding may block or impair the functions of growth-related bacterial components and lead to bacterial growth inhibition. It is also possible that specific IgY binding to bacteria could alter cellular signaling cascades that could result in decreased toxin production and release.

-

(iii)

Opsonization followed by phagocytosis. Nie et al. (2004) determined that IgY improved the phagocytosis of S. aureus by neutrophils. Similarly, Zhen et al. (2008b) showed that phagocytic activity of E. coli by either milk macrophages or by polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocytes increased significantly in the presence of IgY. These results suggest that IgY enhanced phagocytic activity. Structural alterations were observed on the surface of S. typhimurium (Lee et al., 2002) and E. coli O111 (Zhen et al., 2008b) by binding with specific IgY. These changes could be explained by the variation of the electron cloud and/or electric field on the bacterial surface (Lee et al., 2002), resulting in greater vulnerability of the bacterial cells to phagocytosis.

-

(iv)

Toxin neutralization. S. aureus capsular is a major virulence factor involved in the onset of bovine mastitis. Wang et al. (2011) studied the effectiveness of IgY against encapsulated S. aureus. Their results showed that IgY could prevent S. aureus internalization by mammary epithelial cells suggesting toxin neutralization activity, rather than direct growth inhibition as the means through which IgY acts to control mastitis.

4. Applications for IgY administration

The potential applications for using orally administered IgY in the control of enteric and non-enteric infections of either bacterial or viral origin in humans and animals have been studied at length and are summarized in Table 2, Table 3 .

Table 2.

Investigations on the use of specific IgY for the control of enteric diseases.

| Pathogens | Effects of IgY | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Rotavirus | Protecting calves from bovine rotavirus-induced diarrhea | Kuroki et al. (1994) |

| Preventing murine rotavirus in mice | Yolken et al. (1988) | |

| Preventing human rotavirus-induced gastroenteritis in mice | Ebina (1996) | |

| Prevention and treatment of rotavirus-induced gastroenteritis in murine model | Hatta et al. (1993) | |

| Prevention of rotavirus infection in vitro, using IgY against recombinant HRV coat protein, VP8* | Kovacs-Nolan et al. (2001) | |

| Coronavirus | Protecting neonatal calves from bovine coronavirus (BCV)-induced diarrhea | Ikemori et al. (1997) |

| Escherichia coli | Preventing K88+, K99+, 987P + ETEC infection in neonatal piglets | Yokoyama et al. (1992) |

| Protecting neonatal calves from fatal enteric colibacillosis by K99-pilated ETEC | Ikemori et al. (1992) | |

| Inhibiting adhesion of ETEC K88 to piglet intestinal mucus | Jin et al. (1998) | |

| Prevention of ETEC K88+ infection in neonatal and early weaned piglets | Marquardt et al. (1999) | |

| Salmonella | Protecting mice challenged with S. enteritidis or S. typhimurium from salmonellosis | Yokoyama et al. (1998) |

| Preventing fatal salmonellosis in neonatal calves exposed to S. typhimurium or S. dublin | Yokoyama et al. (1998) | |

| Inhibiting adhesion of S. enteritidis to human intestinal cells | Sugita-Konishi et al. (1996) | |

| Yersinia | Protection of rainbow trout against Y. ruckeri infection | Lee et al. (2000) |

| Edwardsiella | Preventing Edwardsiellosis of Japanese eels infected with Edwardsiella tarda | Stevenson et al. (1993) |

| IBDV | Protecting chicks from infectious bursal disease virus | Gutierrez et al. (1993) |

| Staphylococcus | Inhibiting the production of S. aureus enterotoxin-A | Sugita-Konishi et al. (1996) |

| Pseudomonas | Inhibiting the growth of P. aeruginosa | Sugita-Konishi et al. (1996) |

Table 3.

Investigations on the use of specific IgY in the control of non-enteric diseases.

| Pathogens | Effects of IgY | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus mutans | Protecting rats from S. mutans-induced dental caries | Hamada et al. (1991) |

| Snake venoms | Neutralizing the toxic and lethal components of the venoms | Meenatchisundaram et al. (2008) |

| SARS coronavirus | Prevention of SARS-coronavirus infection in vitro | Fu et al. (2006) |

| Avian influenza virus | Protecting birds from avian influenza Subtype H9N2 | Rahimi et al. (2007a) |

4.1. Application of IgY in the control of livestock diseases

4.1.1. Bovine mastitis

Bovine mastitis is a costly disease for the dairy industry. In the United States alone, the annual costs of mastitis have been estimated to be $1.5–2.0 billion ($US). Numerous pathogens can cause mastitis and these can be classified into contagious pathogens (primary Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae) or environmental pathogens (primary E. coli; Riffon et al., 2001).

In our research, we have reported that specific IgY produced by hens immunized with S. aureus and/or E. coli was effective in controlling experimental and clinical mastitis (Zhen et al., 2008a, Zhen et al., 2008b, Zhen et al., 2009). An in vitro study conducted in our laboratory indicated that IgY could inhibit the growth of bacteria by altering the bacterial cell surface thereby reducing the ability of bacteria to adhere to mammary epithelial cells (Zhen et al., 2008b). In a further study, the efficacy of specific IgY to reduce clinical and experimental mastitis caused by S. aureus was demonstrated by improving milk quality through a decrease in somatic cell and bacterial counts in milk (Zhen et al., 2009). The cure rates resulting from the use of IgY for clinical and experimental mastitis were dramatically higher than for untreated animals (Table 4 ). Although conducted with very few animals, these studies indicate that specific IgY has considerable potential as a therapeutic treatment for mastitis in dairy cows.

Table 4.

Comparison of IgY and penicillin for the treatment of experimental and clinical mastitis caused by S. aureusa.

| Treatment | Experimental mastitisb |

Clinical mastitisc |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of mastitic quarters | No. of cured quarters | No. of mastitic quarters | No. of cured quarters | |

| IgY | 6 | 5 (83.3%)⁎ | 6 | 3 (50.0%)⁎ |

| Penicillin | 6 | 4 (66.7%)⁎ | 6 | 2 (33.3%)⁎ |

| No treatment | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

p < 0.05 compared with no treatment in the same group.

Ten milliliters of IgY, at a concentration of 20 mg ml− 1, or penicillin, at a concentration of 100 mg ml− 1, were infused into the mammary glands immediately after the cow's morning and evening milking for six consecutive days.

Mammary glands selected for clinical mastitis treatment met the following criteria: obvious clinical signs of mastitis were detected, S. aureus counts of the milk samples were 100–200 CFU ml− 1, somatic cell counts were more than 5 × 105 cells ml− 1.

Mammary glands selected for inducing experimental mastitis met the following criteria: no clinical signs of mastitis were detected, S. aureus counts of the milk were less than 10 CFU ml− 1 and no other bacteria were detected, somatic cell counts were less than 1 × 105 CFU ml− 1. Experimental mastitis was induced by mammary infusion with 107 CFU ml− 1 of S. aureus.

From Zhen et al. (2009).

4.1.2. Diarrhea in piglets

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is by far the most common cause of enteric colibacillosis encountered in neonatal and post-weaned pigs (Yokoyama et al., 1992). The strains of E. coli associated with intestinal colonization which cause severe diarrhea are the K88, K99 and 987P fimbrial adhesins. Among the ETEC, those expressing the K88+ fimbrial antigen are the most prevalent forms causing E. coli infection world-wide (Rapacz and Hasler-Rapacz, 1986). It has been estimated that K88+ ETEC are responsible for more than half of the piglet mortality which occurs each year (Waters and Sellwood, 1982), causing significant economic loss for the pig industry.

IgY is recognized as an alternative source of antibodies for the prevention of ETEC coli infection because it has been found to inhibit binding of E. coli to the intestinal mucosa (Jin et al., 1998). IgY has been orally administered to piglets and offers a potential prophylactic and therapeutic approach for controlling E. coli-induced diarrhea. Yokoyama et al. (1992) showed that orally administered IgY generated against E. coli K88, K99, or 987P fimbriae was protective against infection from each of the three homologous strains of E. coli in a dose-dependent manner. E. coli K88, K99, and 987P strains adhered equally to porcine epithelial cells from the duodenum and ileum but failed to so in the presence of homologous anti-fimbrial IgY.

A group of researchers at the University of Manitoba (Winnipeg, Canada) have carried out some excellent studies on the passive protective effect of IgY against ETEC K88 fimbriae in the control of neonatal and early-weaned piglets in vitro and in vivo (Jin et al., 1998, Marquardt et al., 1999). In an animal feeding study, 21-day old pigs were challenged with 5 ml of ETEC K88 at a dose of 1012 CFU ml− 1 per piglet. IgY was administered to piglets three times a day for two days. Control piglets (treated with IgY from non-immunized hens) developed severe diarrhea within 12 h and 30% of the pigs died. In contrast, the pigs given IgY from immunized hens exhibited no signs of diarrhea when observed 24 and 48 h after treatment (Table 5 ). Furthermore, the field study showed the suppression of the incidence and severity of diarrhea in 14–18-day-old weaned piglets fed specific IgY powder, which was much lower than in those fed a commercial diet containing an antibiotic. The number of pigs in this study was not large and it would be desirable to repeat this study with a greater number of animals.

Table 5.

Clinical response of 21-day-old pigs after challenge with ETEC K88+ MB and treatment with egg-yolk antibodies.

| Treatmenta | No. of pigs | No. of pigs with diarrhea (FC scoreb) after |

Weight gain (g) | % of pigs dead | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | ||||

| E. coli challenged | 10 | 3/10 | 8/10 | 4/7 | − 36.2 | 30.0% |

| (1.0) | (2.0) | (3.0) | ||||

| E. coli challenged + IgY | 10 | 5/10 | 0/10 | 1/10 | + 90.6 | 0.0% |

| (1.6) | (0.0) | (0.5) | ||||

All the 21-day-old piglets were challenged orally two times (at 0 and 5 h) with a dose of 1012 CFU ml− 1 of viable organism per piglet. Piglets in the E. coli challenged + IgY group were treated with 0.5 g of egg yolk antibodies, three times a day (− 1, 4 and 9 h after the first ETEC challenge) for the first day and once a day for the next two days after the first ETEC challenge.

FC score is the mean fecal consistency score: 0, normal; 1, soft feces; 2, mild diarrhea; 3, severe diarrhea. Pigs with a fecal score of ≤ 1 were considered not to have diarrhea.

From Marquardt et al. (1999).

ETEC can cause severe diarrhea in young animals by proliferation in the small intestine and through the production of two types of enterotoxins including a heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and a family of heat-stable enterotoxins (ST) that includes STa and STb (Dubreuil, 1997). These enterotoxins are crucial virulence factors and therefore effective programs for immunological protection against ETEC-mediated diarrhea should include antitoxic immunity (Cardenas and Clements, 1993). Because of their small size, enterotoxins STa and STb are poorly immunogenic, but they can attain immunogenicity when coupled chemically or genetically to an appropriate carrier (Clements, 1990, Dubreuil et al., 1996).

Antitoxinic antibodies were shown to be important in the prevention of E. coli-induced diarrhea. Considering the limited number of classes of enterotoxins, enterotoxin-based vaccines should provide broad-spectrum protection against various ETEC. In order to make the useful toxoids, polyvalent enterotoxin STa–LTB–STb DNA and protein vaccines endowing immunogenicity to both STa and STb were constructed (You et al., 2011). We immunized laying hens with DNA vaccines and obtained antitoxic antibodies from egg yolks and this was confirmed by indirect ELISA. The polyvalent DNA vaccine pCI–STa–LTB–STb expressed the STa–LTB–STb fusion peptide in vitro in cultured Hela cells. These egg yolk antibodies were able to neutralize the biological activity of ST and LT (You, 2011). Therefore, the trivalent fusion enterotoxin STa–LTB–STb has the potential to serve as a useful toxin-based vaccine which can provide broad protection against ETEC-induced diarrhea.

4.1.3. Diarrhea in calves

Neonatal calf diarrhea caused by bovine rotavirus (BRV) is a common disease and causes high mortality in cattle (Lee et al., 1995). Anti-BRV IgY has been shown to successfully provide protection against BRV infection in calves (Kuroki et al., 1994).

Bovine corona virus (BCV) is an important enteric pathogen that is responsible for both neonatal calf diarrhea and acute diarrhea in adult cattle. BCV may be more severe than BRV as it replicates in the epithelium of both the small and large intestine whereas BRV infects only the small intestine. Ikemori et al. (1997) examined the efficacy of specific IgY antibodies and cow colostrum antibodies to BCV-induced diarrhea in calves. They found that control calves which received no antibodies developed severe diarrhea resulting in all calves dying within 6 days of BCV challenge whereas calves treated with milk containing egg yolk or colostrum had positive weight gains and none of these calves died (Table 6 ). This study was conducted with very few animals and a larger study should be conducted to confirm these findings. However, these results do indicate that orally administered egg yolk or colostral antibodies have the potential to passively protect calves against BCV infection and the effect of IgY was higher than that of colostrum alone indicating that the passive immunization strategy with IgY provided a more efficacious alternative to existing treatments for BCV. The passive protective effects of using anti-ETEC IgY administration on fatal enteric colibacillosis in neonatal calves have also been studied (Ikemori et al., 1992). Calves fed milk containing IgY had only transient diarrhea, 100% survival and exhibited good body weight gains during the course of the study. In contrast, the controls which received no antibody had severe diarrhea and all died within 6 days of infection.

Table 6.

Clinical response of calves to challenge exposure with bovine coronavirus and subsequent treatment with egg yolk powder.

4.2. Applications of IgY in the control of poultry diseases

4.2.1. Salmonellosis

Salmonella infections are thought to be responsible for a variety of acute and chronic diseases of poultry. It has been shown that specific IgY against Salmonella enteritidis or Salmonella typhimurium inhibits bacterial growth in vitro (Lee et al., 2002). Studies have demonstrated that egg derived anti-S. entritidis IgY antibody had a beneficial effect in reducing the colonization of Salmonella in market-aged broilers (Rahimi et al., 2007b, Tellez et al., 2001) (Table 7 ). Whether or not this translates into improvements in broiler performance has not been determined.

Table 7.

Effect of specific IgY on the concentration of Salmonella in the cecum of broiler chickens.

| Age of bird | Log10Salmonella per gram cecal contents |

|

|---|---|---|

| Control | IgY | |

| Day 21 | 5.26b | 1.23a |

| Day 28 | 3.98b | 0.27a |

a,b Means in the same row lacking a common superscript differ significantly (p < 0.01).

From Rahimi et al. (2007b).

The use of whole egg powder (containing antibody) as a feed additive may be an alternative way to reduce the rate of Salmonella contamination of eggs. Gurtler et al. (2004) found that in the experimental group, 13.3% of the eggs were Salmonella positive, which was significantly lower than the 29.4% Salmonella-positive eggs in the control group (p ≤ 0.001) (Table 8 ). However, it must be pointed out that the majority of the Salmonella was found on the shell and there were only modest differences in Salmonella numbers in the albumen and yolk. Whether or not this translates into any less health risk for consumers of egg products is not known at this time.

Table 8.

Rate of Salmonella isolation in eggs laid by hens after oral application of IgY egg powder.

| Parts | % Eggs with Salmonella |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgY | Control | p value | |

| Whole eggs | 13.3 | 29.4 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Egg shell | 13.3 | 29.2 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Albumen | 0.3 | 0.5 | n.s. |

| Yolk | 0.6 | 2.4 | p ≤ 0.05 |

From Gurtler et al. (2004).

4.2.2. Campylobacteriosis

Campylobacter jejuni has become a major concern to the commercial broiler, turkey and commercial egg-producing flocks in all countries. Tsubokura et al. (1997) used egg yolk antibodies for prophylactic and therapeutic applications in Campylobacter-infected chickens. In a prophylaxis experiment, it was found that these antibodies caused a 99% decrease in the number of Campylobacter observed, whereas in a therapy trial (antibodies were given after establishment of the infection), the number of bacteria in the feces was 80–95% lower. Unfortunately, bird performance was not monitored in this study.

4.2.3. Infectious bursal disease

Infectious bursal disease (IBD) is an acute, highly contagious disease of young chickens caused by IBD virus (Chettle et al., 1989). Early sub-clinical infections which usually result in immunosuppression are the most important form of this disease because of the large economic loss that results from their presence. Chickens immunosuppressed by early IBD infections do not respond well to vaccination and show increased susceptibility to other diseases such as bacterial infection with E. coli or viral infections like bronchitis or inclusion body hepatitis (Muhammad et al., 1996). Antibiotic therapy is the most readily-available approach for controlling IBD-induced secondary bacterial infections in affected flocks. It has been shown that specific IgY has a great potential as an alternative to antibiotics for IBD. Muhammad et al. (2001) demonstrated that yolks from hyper-immunized hens can be used to control IBD in commercial laying hens. The IBD infected broilers (28 days old) treated with the yolk induced 80% recovery while all the control (untreated) birds died.

4.2.4. Newcastle disease

Newcastle disease is a severe viral infection causing a respiratory nervous disorder in several species of poultry including chickens and turkeys. This disease is endemic in commercial poultry from many countries and can cause great economic loss due to high mortality rates (Lancaster, 1976). Vaccination has been used to prevent this disease in endemic areas, but vaccines are not always effective and vaccinated flocks may still be infected. When outbreaks of Newcastle disease occur in a commercial poultry flock, antibiotics may be given to prevent secondary bacterial infections which are usually triggered by this disease. It has been shown that egg yolk antibodies conferred protection in chickens against Newcastle disease (Box et al., 1969, Wills and Luginbuhl, 1963). Wills and Luginbuhl (1963) have found that subcutaneous administration of egg yolk containing high levels of IgY antibody specific to Newcastle disease protected 80% of the birds during a four-week study period.

4.3. Applications of IgY in the control of aquatic diseases

4.3.1. Shrimp white spot syndrome virus

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) is a virulent pathogen causing high mortality and significant economic loss in cultured shrimp operations worldwide (Wongteerasupaya et al., 1995). As with other invertebrates, shrimp lack a true adaptive immune response system (Kimbrell and Beutler, 2001). However, shrimp may exhibit a quasi-immune response which possibly shows WSSV-specific effects (Witteveldt et al., 2004, Wu et al., 2002). WSSV can be neutralized by chicken IgY produced against a truncated fusion protein of VP28 and VP19 (Kim et al., 2004) and therefore, passive immunization with IgY against WSSV has potential for immunotherapeutic application to prevent WSSV infection in shrimp.

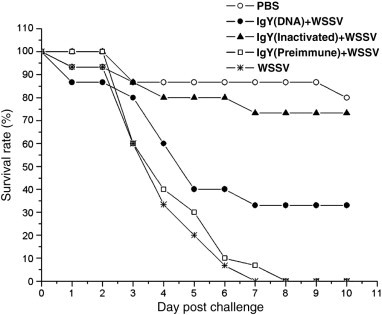

Some researchers have demonstrated passive immunization by anti-viral egg yolk antibodies (IgY) (Arasteh et al., 2004, Kweon et al., 2000). However, our research work (Lu et al., 2008) represents the first report of the passive immunization of shrimp with IgY obtained from the egg yolk of chickens vaccinated with a DNA vaccine comprising genes encoding structural proteins of WSSV or with inactivated WSSV. Our work showed that IgY antibodies have a high affinity for WSSV and maintained good biological and neutralization activity especially when induced by the traditional inactivated vaccine. IgY antibody induced by the DNA vaccine was also able to neutralize disease in shrimp experimentally challenged with WSSV but was still inferior to inactivated WSSV (Lu et al., 2008). Using specific IgY from hens immunized with inactivated WSSV and DNA vaccine to neutralize WSSV, the challenged shrimp had 73.3 and 33.3% survival, respectively (Fig. 2 ). As well, the effectiveness of IgY provided by intramuscular injection, oral administration, and immersion was investigated in crayfish (Procambius clarkiaii) challenged with WSSV (Lu et al., 2009). Our results showed that immunization of specific IgY antibodies through intramuscular injection, oral administration or immersion were all effective means of protecting crayfish against WSSV. Unfortunately, these are labor intensive techniques and may have limited application under commercial aquaculture conditions where crayfish are raised in the ocean.

Fig. 2.

Effect of IgY on the survival rate of shrimp challenged with white spot syndrome virus.

From Lu et al., 2008.

Egg yolk antibodies can be harvested in a more cost efficient and convenient manner compared with production of antibody from mammals (Mine and Kovacs-Nolan, 2002). IgY in egg yolk could be prepared in different forms such as egg yolk powder, purified powder and liquor which may provide a feasible and significant way forward in research using antibodies against WSSV.

4.3.2. Y. ruckeri

The effectiveness of IgY in passive immunization of rainbow trout against Y. ruckeri infection has been studied (Lee et al., 2000). Y. ruckeri is the aetiological agent of enteric red mouth disease, a systemic bacterial septicaemia, principally affecting farmed rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Stevenson et al., 1993). Y. ruckeri could persist for long periods in carrier fish and are shed in feces, representing a continuing source of infection. If a population of asymptomatic carrier fish could be adequately cleared by oral administration of anti-Y. ruckeri antibody, such treatment might be a cost-effective alternative approach to the slaughter of a stock of fish with a potential health risk. Rainbow trout fed with anti-Y. ruckeri IgY, 2 h before an immersion challenge with Y. ruckeri, showed a lower mortality rate after 8 days than did fish fed unsupplemented IgY feed before the challenge (Lee et al., 2000). The fish fed IgY also appeared to have fewer infections after 8 days, based on organ and intestinal cultures. In a subsequent trial, the IgY-fed fish had lower mortality than fish receiving unsupplemented IgY feed (Lee et al., 2000). The percentage of IgY-fed fish carrying Y. ruckeri in their intestinal samples appeared to be lower than in the untreated controls, regardless of whether the IgY containing feed was given before or after the challenge. The oral administration of specific IgY against fish pathogens could provide an alternative method to antibiotics and chemotherapy for prevention of bacterial diseases of fish in fish farm.

4.3.3. E. tarda

E. tarda is another important fish pathogen which is spread by infection through the intestinal mucosa (Noga, 1996). Edwardsiellosis in Japanese eels has become a serious problem for the eel farming industry (Wakabayashi and Egusa, 1973). Egg yolk antibodies have been investigated for the prevention of this infectious disease because the use and misuse of antibiotics has led to growing problems with drug residues in fish products and increased bacterial resistance (Gutierrez et al., 1993, Hatta et al., 1994). Anti-E. tarda IgY were simultaneously administered orally to Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica) with the pathogenic bacteria (105–106 CFU per fish). The non-treated infected eels died within 15 days whereas the eels receiving IgY survived and no disease symptoms were observed, suggesting that anti-E. tarda IgY is effective in preventing edwardsiellosis (Gutierrez et al., 1993). Again limited numbers of eels were used in this study and a repeat with greater numbers would certainly be welcomed.

5. Limitations of IgY technology

There are limitations to the use of IgY for oral passive immunotherapy due to its susceptibility to proteolysis. IgY is fairly resistant to digestion by intestinal proteases (Hatta et al., 1993, Shimizu et al., 1988). However, it was found that the activity of IgY was decreased at pH 3.5 and completely lost at pH 3.0 (Shimizu et al., 1988). IgY has a serum half-life of 1.85 days in newborn pigs. This is shorter than the reported serum half-life of 12 to 14 days for homologous IgG (colostral antibodies). The fraction of IgY absorbed into the circulation when administered in pigs decreased with increasing age of pigs (Yokoyama et al., 1993).

Since the primary target site of IgY is the small intestine, in order for it to function it is essential to find an effective method to protect IgY against peptic digestion and acidity in the stomach. It has been shown that microencapsulation can be an effective method for protecting IgY from gastric inactivation (Chang et al., 2002, Cho et al., 2005, Kovacs-Nolan and Mine, 2005, Li et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009), but this process will undoubtedly add additional costs. Additional study will be needed before microencapsulation can be applied under commercial conditions.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that IgY is effective against many Gram-negative bacteria. In contrast, inhibition activity of IgY on Gram-positive bacteria has only occasionally been reported (Sugita-Konishi et al., 1996, Zhen et al., 2008a, Zhen et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2011). This may be due to the fact that Gram-positive bacteria have a more compact cell wall compared with Gram-negative bacteria. However, this clearly limits the types of diseases that can be treated with IgY technology.

The objective to treatment with IgY is not always prevention of a disease but sometimes simply a reduction of infectious agents (Kuroki et al., 1993). Unlike mammalian IgG, IgY does not bind complement or acts as an opsonin in phagocytosis. Therefore, IgY are unable to kill bacteria directly. It was also shown that IgY antibodies were not able to displace E. coli K88+ MB once bound to the mucosal receptor. This indicates that the antibodies have a lower affinity for the receptor than that of K88+ fimbriae. Since IgY could not remove previously bound E. coli K88+ MB from the mucus, a prophylactic use for IgY is suggested (Jin et al., 1998). However, therapeutic effects of IgY in the control of infections have been reported, such as E. coli K88 in piglets (Yokoyama et al., 1992, Wiedemann et al., 1991), C. jejuni in chickens (Tsubokura et al., 1997) and Salmonella in mice (Yokoyama et al., 1998).

At present, the production cost of high quality IgY antibodies is higher than the cost of routine antibiotics (Casadevall and Scharff, 1994). Therefore, the development of methods for large-scale production of IgY with high recovery and purity are needed. The method should be simple, economical and requires few chemicals. In addition, there is no consensus on the most suitable IgY extraction method for commercial application (Schade et al., 2005) and this requires further study.

6. Conclusions

Oral administration of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin appears to have considerable potential as a means of controlling infectious diseases of bacterial and viral origin and may be the disease treatment of the future. To date, IgY technology has been used for the treatment of livestock diseases such as mastitis and diarrhea, poultry diseases such as Salmonella, Campylobacteriosis, infectious bursal disease and Newcastle disease, as well as aquatic diseases like shrimp white spot syndrome virus, Y. ruckeri and E. tarda. Some advantages of IgY in the control of animal diseases are:

-

1.

They are highly effective.

-

2.

They are cost effective.

-

3.

Collection of eggs is non-invasive.

-

4.

The treatment is safe and live organisms are not used.

-

5.

The procedure is environmentally friendly.

-

6.

No toxic residues are produced and there is no development of resistance.

-

7.

The treatment can be used to control many different types of pathogens.

Acknowledgments

The work from our laboratory that is reviewed here was supported by funds from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30371053; 30871806; 31001053). The authors gratefully thank Professor Philip A. Thacker from University of Saskatchewan for his valuable suggestion and for revising the manuscript.

References

- Arasteh N., Aminirissehei A.H., Yousif A.N., Albright L.J., Durance T.D. Passive immunization of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins (IgY) Aquaculture. 2004;231:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Box P.G., Stedman R.A., Singleton L. Newcastle Disease: I. The use of egg yolk derived antibody for passive immunisation of chickens. J Comp Pathol. 1969;79:495–506. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(69)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlander D., Kollberg H., Wejaker P.E., Larsson A. Peroral immunotherapy with yolk antibodies for the prevention and treatment of enteric infections. Immunol Res. 2000;21:1–6. doi: 10.1385/IR:21:1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas L., Clements J.D. Development of mucosal protection against the heat-stable enterotoxin (ST) of Escherichia coli by oral immunization with a genetic fusion delivered by a bacterial vector. Infect Immunol. 1993;61:4629–4636. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4629-4636.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A., Scharff M.D. Serum therapy revisited: Animal models of infection and development of passive antibody therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1695–1702. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casewell M., Friis C., Marco E., McMullin P., Phillips I. The European ban on growth-promoting antibiotics and emerging consequences for human and animal health. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:159–161. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.M., Lee Y.C., Chen C.C., Tu Y.Y. Microencapsulation protects immunoglobulin in yolk (IgY) specific against Helicobacter pylori urease. J Food Sci. 2002;67:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chettle N.J., Stuart C., Wyeth P.J. Outbreak of virulent infectious bursal disease in East Anglia. Vet Rec. 1989;125:271–272. doi: 10.1136/vr.125.10.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.H., Lee J.J., Park I.B., Huh C.S., Baek Y.J., Park J. Protective effect of microencapsulation consisting of multiple emulsification and heat gelation processes on immunoglobulin in yolk. J Food Sci. 2005;70:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Clements J.D. Construction of a nontoxic fusion peptide for immunization against Escherichia coli strains that produce heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1159–1166. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1159-1166.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. Using egg antibodies to treat diseases. In: Sim J.S., Nakai S., Guenter W., editors. Egg Nutr Biotechnol. CAB International; Wallingford: 1999. pp. 351–370. [Google Scholar]

- Cook M.E. Antibodies: alternatives to antibiotics in improving growth and feed efficiency. Appl Poult Res. 2004;13:106–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell G.L. Why and how antibiotics are used in swine production. Anim Biotechnol. 2002;13:7–27. doi: 10.1081/ABIO-120005767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos-Pantoja L., Ortega-Vinuesa J.L., Bastos-Gonzalez D., Hidalgo-Alvarez R. A comparative study between the adsorption of IgY and IgG on latex particles. Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11:657–673. doi: 10.1163/156856200743931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil J.D., Letellier A., Harel J. A recombinant Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin b (STb) fusion protein eliciting neutralizing antibodies. FEMS Immunol Med Mic. 1996;13:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil J.D. Escherichia coli STb enterotoxin. Micro. 1997;143:1783–1795. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebina T. Prophylaxis of rotavirus gastroenteritis using immunoglobulin. Arch Virol Suppl. 1996;12:217–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhard M.H., Schmidt P., Zinsmeister P., Hofmann A., Munster U., Kaspers B. Adjuvant effects of various lipopeptides and interferon-gamma on the humoral immune response of chickens. Poult Sci. 2000;79:1264–1270. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger E.A., Van Loo J., Fahey G.C. Nutritional responses to the presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of domesticated animals: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2003;43:19–60. doi: 10.1080/10408690390826446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer J., Firca J., Leventhal J., Blondin B., Malcolm A., Ivancic D. IgY antiporcine endothelial cell antibodies effectively block human antiporcine xenoantibody binding. Xenotransplantation. 1999;6:98–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.1999.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C.Y., Huang H., Wang X.M., Liu Y.G., Wang Z.G., Cui S.J. Preparation and evaluation of anti-SARS coronavirus IgY from yolks of immunized SPF chickens. J Virol Methods. 2006;133:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J.S., Voss E.W. Conformational state of chicken 7S immunoglobulin. Immunochem. 1974;11:461–465. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(74)90081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtler M., Methner U., Kobilke H., Fehlhaber K. Effect of orally administered egg yolk antibodies on Salmonella enteritidis contamination of hen's eggs. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2004;51:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M.A., Miyazaki T., Hatta H., Kim M. Protective properties of egg yolk IgY containing anti-Edwardsiella tarda antibody against paracolo disease in the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica Temminck & Schlegel. J Fish Dis. 1993;16:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada S., Horikoshi T., Minami T., Kawabata S., Hiraoka J., Fujiwara T. Oral passive immunization against dental caries in rats by use of hen egg yolk antibodies specific for cell-associated glucosyltransferase of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4161–4167. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4161-4167.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta H., Tsuda K., Akachi S., Kim M., Yamamoto T., Ebina T. Oral passive immunization effect of anti-human rotavirus IgY and its behavior against proteolytic enzymes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1077–1081. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta H., Mabe K., Kim M., Yamamoto T., Gutierrez M.A., Miyazaki T. Prevention of fish disease using egg yolk antibody. In: Sim J.S., Nakai S., editors. Egg Uses and Processing Technologies: New Developments. CAB International; Wallingford: 1994. pp. 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ikemori Y., Kuroki M., Peralta R.C., Yokoyama H., Kodama Y. Protection of neonatal calves against fatal enteric colibacillosis by administration of egg yolk powder from hens immunized with K99-piliated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Am Vet Res. 1992;53:2005–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemori Y., Ohta M., Umeda K., Icatlo F.C., Kuroki M., Yokoyama H. Passive protection of neonatal calves against bovine coronavirus-induced diarrhea by administration of egg yolk or colostrum antibody powder. Vet Microbiol. 1997;58:105–111. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00144-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson A.K., Smith C.I., Hammarstrom L. Biological properties of yolk immunoglobulins. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371:685–690. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1941-6_145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L.Z., Samuel K., Baidoo K., Marquardt R.R., Frohlich A.A. In vitro inhibition of adhesion of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 to piglet intestinal mucus by egg yolk antibodies. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachatourians G.G. Agricultural use of antibiotics and the evolution and transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;159:1129–1136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.K., Jang I.K., Seo H.C., Shin S.O., Yang S.Y., Kim J.W. Shrimp protected from WSSV disease by treatment with egg yolk antibodies (IgY) against a truncated fusion protein derived from WSSV. Aquaculture. 2004;237:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.Y., Kil D.Y., Oh H.K., Han I.K. Acidifier as an alternative material to antibiotics in animal feed. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2005;18:1048–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrell D.A., Beutler B. The evolution and genetics of innate immunity. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:256–267. doi: 10.1038/35066006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Nolan J., Sasaki E., Yoo D., Mine Y. Cloning and expression of human rotavirus spike protein, VP8* in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:1183–1188. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Nolan J., Mine Y. Microencapsulation for the gastric passage and controlled intestinal release of immunoglobulin Y. J Immunol Methods. 2005;296:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritas S.K., Morrison R.B. Evaluation of probiotics as a substitute for antibiotics in a large pig nursery. Vet Rec. 2005;56:447–448. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.14.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman R., Wiedemann V., Schmidt P., Wanke R., Linckh E., Losch U. Chicken egg antibodies for prophylaxis and therapy of infectious intestinal diseases. I. Immunization and antibody determination. J Vet Med B. 1988;35:610–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1988.tb00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki M., Ikemori Y., Yokoyama H., Peralta R.C., Icatlo F.C., Jr, Kodama Y. Passive protection against bovine rotavirus-induced diarrhea in murine model by specific immunoglobulins from chicken egg yolk. Vet Microbiol. 1993;37:135–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90188-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki M., Ohta Y., Ikemori Y., Peralta R.C., Yokoyama H., Kodama Y. Passive protection against bovine rotavirus in calves by specific immunoglobulins from chicken egg yolk. Arch Virol. 1994;138:143–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01310045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweon C.H., Kwon B.J., Woo S.R., Kim J.M., Woo G.H., Son D.H. Immunoprophylactic effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) in piglets. J Vet Med Sci. 2000;62:961–964. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster J.E. A history of Newcastle disease with comments on its economic effects. World Poult Sci J. 1976;32:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A., Balow R., Lindahl T.L., Forsberg P. Chicken antibodies: taking advantage of evolution—a review. Poult Sci. 1993;72:1807–1812. doi: 10.3382/ps.0721807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Babiuk L.A., Harland R., Gibbons E., Elazhary Y., Yoo D. Immunological response to recombinant VP8* subunit protein of bovine rotavirus in pregnant cattle. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2477–2483. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.B., Mine Y., Stevenson R.M.W. Effects of hen egg yolk immunoglobulin in passive protection of rainbow trout against Yersinia ruckeri. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:110–115. doi: 10.1021/jf9906073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.N., Sunwoo H.H., Menninen K., Sim J.S. In vitro studies of chicken egg yolk antibody (IgY) against Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium. Poult Sci. 2002;81:632–641. doi: 10.1093/ps/81.5.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.Y., Jin L.J., McAllister T.A., Stanford K., Xu J.Y., Lu Y.N. Chitosan–alginate microcapsules for oral delivery of egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:2911–2917. doi: 10.1021/jf062900q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.Y., Jin L.J., Uzonna J.E., Li S.Y., Liu J.J., Li H.Q. Chitosan–alginate microcapsules for oral delivery of egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY): in vivo evaluation in a pig model of enteric colibacillosis. Vet Immunol Immunopharmacol. 2009;129:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.N., Liu J.J., Jin L.J., Li X.Y., Zhen Y.H., Xue H.Y. Passive protection of shrimp against white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) using specific antibody from egg yolk of chickens immunized with inactivated virus or a WSSV–DNA vaccine. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;25:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.N., Liu J.J., Jin L.J., Li X.Y., Zhen Y.H., Xue H.Y. Passive immunization of crayfish (Procambius clarkiaii) with chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) against white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;159:750–758. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt R.R., Jin L.Z., Kim J.W., Fang L., Frohlich A.A., Baidoo S.K. Passive protective effect of egg-yolk antibodies against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88+ infection in neonatal and early-weaned piglets. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;23:283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenatchisundaram S., Parameswari G., Michael A., Ramalingam S. Neutralization of the pharmacological effects of cobra and krait venoms by chicken egg yolk antibodies. Toxicon. 2008;52:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine Y., Kovacs-Nolan J. Chicken egg yolk antibodies as therapeutics in enteric infectious disease: a review. J Med Food. 2002;5:159–169. doi: 10.1089/10966200260398198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad K., Anwar M.S., Yaqub M.T. Failure of vaccines to control infectious bursal disease in commercial poultry. Pak Vet J. 1996;16:119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad K., Rabbi F., Hussain I., Riaz A., Saeed K., Hussain T. Passive immunization against infectious bursal disease in chicks. Int J Agric Biol. 2001;3:413–415. [Google Scholar]

- Narat M. Production of antibodies in chickens. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2003;41:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nie R., Wu D., Hu G., Zhang J., Yang H., Wen Z. Effect of specific egg yolk immunoglobulins on phagocytosis by neutrophils. Chin J Vet Med. 2004;12:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Noga E.J. Fish disease: diagnosis and treatment. Mosby-Year Book Inc.; St. Louis: 1996. pp. 147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi S., Salehifar E., Ghorashi S.A., Grimes J.L., Torshizi M.A.K. The effect of egg-derived antibody on prevention of avian influenza subtype H9N2 in layer chickens. Int J Poult Sci. 2007;6:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi S., Salehifar E., Ghorashi S.A., Grimes J.L., Torshizi M.A.K. Prevention of Salmonella infection in poultry by specific egg-derived antibody. Int J Poult Sci. 2007;6:230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rapacz J., Hasler-Rapacz J. Polymorphism and inheritance of swine small intestinal receptors mediating adhesion of three serological variants of Escherichia coli-producing K88 pilus antigen. Anim Genet. 1986;17:305–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1986.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffon R., Sayasith K., Khalil H., Dubreuil P., Drolet M., Lagace J. Development of a rapid and sensitive test for identification of major pathogens in bovine mastitis by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2584–2589. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2584-2589.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M.E., Orlans E., Buttress N. Immunoglobulin classes in the hen's eggs: their segregation in yolk and white. Eur J Immunol. 1974;4:521–523. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830040715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade R., Calzado E.G., Sarmiento R., Chacana P.A., Porankiewicz-Asplund J., Terzolo H.R. Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgY-technology): a review of progress in production and use in research and human and veterinary medicine. Altern Lab Anim. 2005;33:129–154. doi: 10.1177/026119290503300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Fitzsimmons R.C., Nakai S. Anti-E. coli immunoglobulin Y isolated from egg yolk of immunized chickens as a potential food ingredient. J Food Sci. 1988;53:1360–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Sim J.S., Sunwoo H.H., Lee E.N. Ovoglobulin IgY. In: Naidu A.S., editor. Natural food antimicrobial systems. CRC Press; New York: 2000. pp. 227–252. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson R.M.W., Flett D., Raymond B.T. Enteric redmouth (ERM) and other enterobacterial infections of fish. In: Inglis R., Roberts J., Bromage N.R., editors. Bacterial diseases of fish, V. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1993. pp. 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sugita-Konishi Y., Shibata K., Yun S.S., Hara-Kudo Y., Yamaguchi K., Kumagai S. Immune functions of immunoglobulin Y isolated from egg yolk of hens immunized with various infectious bacteria. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:886–888. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., Mo W., Ji Y., Liu S. Preparation and mass spectrometric study of egg yolk antibody (IgY) against rabies virus. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:708–712. doi: 10.1002/rcm.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taras D., Vahjen W., Simon O. Probiotics in pigs—modulation of their intestinal distribution and of their impact on health and performance. Livest Sci. 2007;108:229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tellez G., Petrone V.M., Escorcia M., Morishita T.Y., Cobb C.W., Villaseñor L. Evaluation of avian-specific probiotic and Salmonella enteritidis-, Salmonella typhimurium-, and Salmonella heidelberg-specific antibodies on cecal colonization and organ invasion of Salmonella enteritidis in broilers. J Food Prot. 2001;64:287–291. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubokura K., Berndtson E., Bogstedt A., Kaijser B., Kim M., Ozeki M. Oral administration of antibodies as prophylaxis and therapy in Campylobacter jejuni-infected chickens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:451–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.3901288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.L., Dritz S.S., Minton J.E. Review: alternatives to conventional antimicrobials in swine diets. Prof Anim Scient. 2001;17:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi H., Egusa S. Edwardsiella tarda (Paracolobactrum anguillimortiferum) associated with pond-cultured eel disease. Bull Jpn Soc Sci Fish. 1973;39:931–936. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.H., Li X.Y., Jin L.J., You J.S., Zhou Y., Li S.Y. Characterization of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins (IgYs) specific for the most prevalent capsular serotypes of mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus. Vet Microbiol. 2011;149:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr G.W., Magor K.E., Higgins D.A. IgY: clues to the origins of modern antibodies. Immunol Today. 1995;16:392–408. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J.R., Sellwood R. The 2nd world congress on genetics applied to livestock production, Madrid. 1982. Aspects of genetic resistance to K88 E. coli in pigs; p. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann V., Linckh E., Kuhlmann R., Schmidt P., Losch U.. Chicken egg antibodies for prophylaxis and therapy of infectious intestinal diseases. V. In vivo studies on protective effects against Escherichia coli diarrhea in pigs. J Vet Med B. 1991;38:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1991.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills F.K., Luginbuhl R.E. The use of egg yolk for passive immunization of chickens against Newcastle disease. Avian Dis. 1963;7:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windisch W.M., Schedle K., Plitzner C., Kroismayr A. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(Suppl):E140–E148. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witteveldt J., Vlak J.M., van Hulten M.C.W. Protection of Penaeus monodon against white spot syndrome virus using a WSSV subunit vaccine. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004;16:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongteerasupaya C., Vicker J.E., Sriurairatana S., Nash G.L., Akarajamorn A., Tassanakajon A. A non-occluded, systemic baculovirus that occurs in cells of ectodermal and mesodermal origin and causes high mortality in the black tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon. Dis Aquat Organ. 1995;21:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.L., Nishioka T., Mori K., Nishizawa T., Muroga K. A time-course study on the resistance of Penaeus japonicus induced by artificial infection with white spot syndrome virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2002;13:391–403. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2002.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Peralta R.C., Diaz R., Sendo S., Ikemori Y., Kodama Y. Passive protective effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins against experimental enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in neonatal piglets. Infect Immun. 1992;60:998–1007. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.998-1007.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Peralta R.C., Sendo S., Ikemori Y., Kodama Y. Detection of passage and absorption of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs by use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and fluorescent antibody testing. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:867–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Umeda K., Peralta R.C., Hashi T., Icatlo F.C., Jr, Kuroki M. Oral passive immunization against experimental salmonellosis in mice using chicken egg yolk antibodies specific for Salmonella enteritidis and S. typhimurium. Vaccine. 1998;16:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)80916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yolken R.H., Leister F., Wee S.B., Miskuff R., Vonderfecht S. Antibodies to rotavirus in chickens' eggs: a potential source of antiviral immunoglobulins suitable for human consumption. Pediatrics. 1988;81:291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J.S., Xu Y.P., He M.L., McAllister T.A., Thacker P.A., Li X.Y. Protection of mice against enterotoxigenic E. coli by immunization with a polyvalent enterotoxin comprising a combination of LTB, STa, and STb. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:1885–1893. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You JS. Recombinant polyvalent enterotoxin vaccines against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis, Dalian University of Technology, China; 2011.

- Zhen Y.H., Jin L.J., Guo J., Li X.Y., Li Z., Fang R. Characterization of specific egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) against mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;105:1529–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen Y.H., Jin L.J., Guo J., Li X.Y., Lu Y.N., Chen J. Characterization of specific egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) against mastitis-causing Escherichia coli. Vet Microbiol. 2008;130:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen Y.H., Jin L.J., Li X.Y., Guo J., Li Z., Zhang B.J. Efficacy of specific egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) to bovine mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Vet Microbiol. 2009;133:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]