The emergence and spread of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from Wuhan, China, have become a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, designated by World Health Organization. As of February 26, 2020, the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China has received a total of 77,663 confirmed cases from across China.1 As of February 26, 126 confirmed cases were reported from Hong Kong (HK), Macao, and Taiwan, and 1804 from 37 countries worldwide.1 During the previous outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in HK and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in South Korean, very few pediatric patients were reported, respectively.2 , 3 Despite a high mortality rate of SARS and MERS in the adults, there were no fatalities in the pediatric patients.2 , 3 Children appeared to have a milder form of the disease caused by the coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2.2 , 3

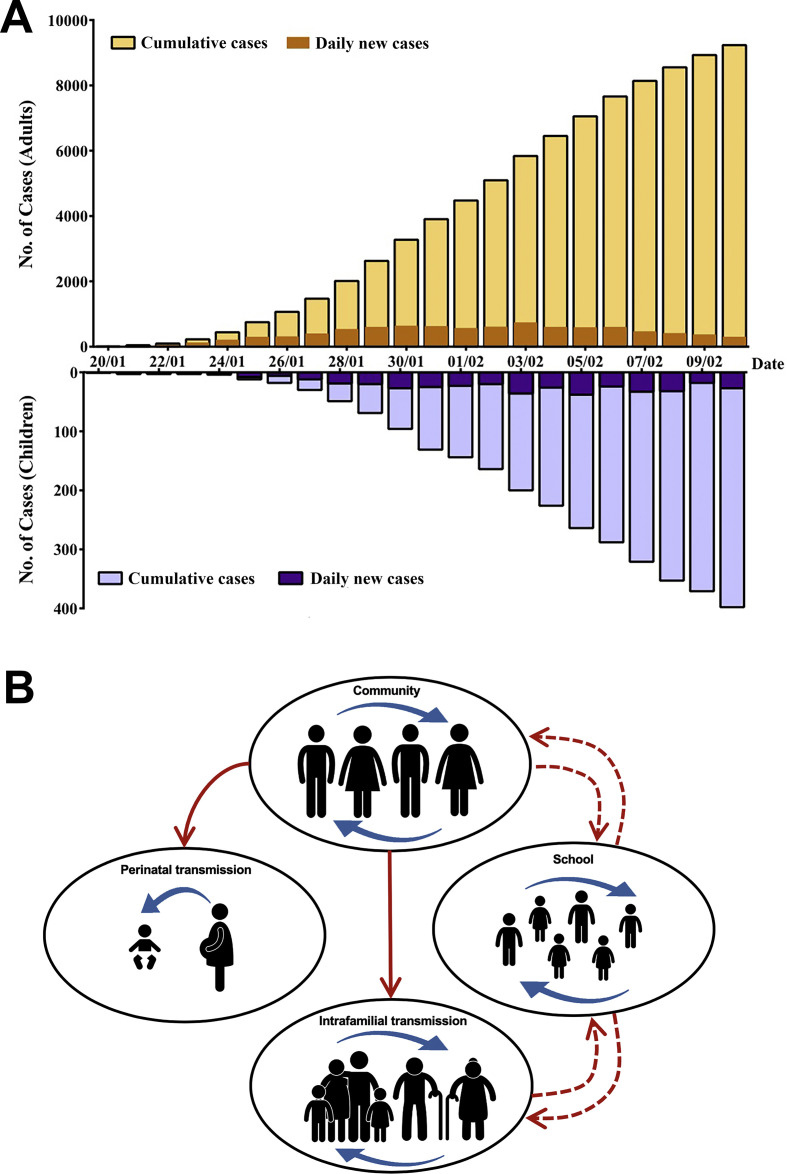

The first confirmed pediatric case of SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported in Shenzhen on January 20.4 As of February 10, a total of 398 confirmed pediatric cases and 10,924 adult cases were reported nationwide, excluding the Hubei province (Fig. 1 A). The data from Hubei province was incomplete because children were rarely screened for SARS-CoV-2 initially. However, a recent study that analyzed 44,672 laboratory-confirmed cases from across China as of February 11, 2020, only 416 (0.9%) were less than 10 years of age and 549 (1.2%) between 10 and 20 years of age.5 In this outbreak, with the increase in the number of adult contacts who turned out to be the infected, the number of pediatric infections also increased concomitantly. With more diagnostic detection done, the proportion of mild infections mainly in children and young adults became higher.5 The formation of the so-called “second-generation” infections in a short period of time indicates that the virus is highly contagious.

Figure. 1.

Accumulated and daily new case numbers of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in children in China and the transmission dynamics. (A) Accumulated and daily new case numbers in China outside Hubei province between January 20 and February 10, 2020. Upper panel shows total case number of adults; lower panel the case number of children. (B) Transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. During the emerging stage of the COVID-19, the infection starts from person-to-person transmission in the community, almost exclusively in adults. The virus further spreads to the family to cause intrafamilial transmission, especially to the elderly and children, who are vulnerable to the infection. Perinatal infection can occur if the baby is born to a pregnant woman with confirmed infection via vaginal delivery. If the disease further extends without being contained, the outbreak may go into the explosion stage, when the school transmission mixed with a wider community spread can occur. The children at that stage can become a main spreader of the virus. The red lines indicate the transmission route with confirmed evidence in the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in China, and the red dotted lines indicate the transmission route that may happen if the outbreak becomes more extensive afterwards.

Humans can be infected readily by respiratory droplets containing the virus. Natural infections are therefore assumed to occur through respiratory route. Coronavirus can also be transmitted by contact with contaminated objects, such as toys and doorknobs. A previous SARS outbreak occurred at a housing complex in HK where more than 300 residents were infected, suggesting airborne or aerosol transmission can sometimes occur.6 As shown in Fig. 1B, during the emerging stage of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, the infection was disseminated by person-to-person transmission in the community almost exclusively among adults. After the stage, likely after mid-January, 2020, the virus further spread to the family via infected adults to cause intrafamilial transmission, especially transmission to the elderly and children, who are vulnerable to the infection. The first pediatric case was identified at that time in a familial cluster.4 With the progression of the outbreak, the first infant case was reported from Xiaogan, Hubei province.7 This is a 3-month-old female infant who had fever for one day. She was admitted on January 26, 2020 with the following blood testing results: white blood cell (WBC) count 9680/mm3 (neutrophil 45% and lymphocyte 44%). Throat swab test for influenza was negative. Chest radiograph taken on admission and CT 3 days later showed only mildly increased infiltrates at bilateral lung. Before she was admitted, her parents were symptomless. Her father started to have fever and fatigue on February 2, 8 days after she was admitted. A chest CT showed a ground glass opacity at lingulate lobe of left lung, and his throat swab was also positive for SARS-CoV-2. The infant's mother had no fever, cough or diarrhea, but the mother's throat swab testing showed positive for the virus on two consecutive days, February 3 and 4. The infant was tested positive by throat swab on January 27 (day 2), January 30 (day 5), and negative on February 3 (day 9), 5 (day 11), and 9 (day 15). The infant's urine, stool and sputum were tested negative; however, on February 9, a test on stool was positive. After appropriate supportive treatment, she was discharged uneventfully on February 10, 2020. This report showed an infant who was diagnosed to have the infection prior to the onset of the illness in her parents. A recent study on 9 hospitalized infants also found families of these infants had at least 1 infected family member, with the infant's infection occurring after the family member's infection.8 The infant case report by Zhang et al. therefore raised a question if the infant showed a shorter period of incubation than adults or her parents actually acquire the infection from the baby. Nevertheless, all these children belonged to familial cluster circles, so aggregative onset is an important feature in pediatric cases, and this is also a strong indicator that the virus is highly contagious.

The first pediatric case outside Hubei province was reported from Shanghai, China.9 This is a 7-year-old boy who complained fever for 1 day. The boy with his father returned from Wuhan on January 11. His father also had fever since January 14. The father was admitted to a hospital because of fever and progressive cough, and soon was diagnosed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on January 19. Blood test showed WBC 16,000/mm3 (neutrophil 70% and lymphocytes 23%) and normal platelet and hemoglobulin. Nasal and throat swabs taken on January 19 were positive for SARS-CoV-2. Follow-up testing for SARS-CoV-2 on January 24 (day 5) and January 28 (day 9) were still positive but turned negative on January 31 (day 12) and February 1 (day 13). He recovered gradually after supportive treatment. The child's mother, who did not go to Wuhan but came to hospital to take of him was tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by nasal and throat swabs. The mother remained symptomless throughout his admission. The case reported by Cai et al. probably was the first evidence indicating children as a source of adult infection.9

Perinatal infection can occur if the baby is born to a pregnant woman with confirmed infection (Fig. 1B). A recent study by Chen et al. reported the clinical characteristics of nine livebirths born to nine pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 via cesarean section; all nine neonates were later confirmed negative for the infection.10 We assume that neonates born to infected mothers via vaginal delivery could still be at risk for the infection due to close baby-mother contact during the delivery. The retrospective case report by Chen et al., however, still suggests that there is no evidence of intrauterine infection.10 As of February 20, 2020, there were 3 neonatal cases in China.1 The first case was a 17-day-old male newborn, who contracted the infection via contact with his parents, who have had fever and cough for 3 days.11 The baby, also from Wuhan, was found to have runny nose and vomiting for one week before he was brought to the hospital. He was then tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by a throat swab test. The initial WBC count was 7660/mm3 (neutrophil 15% and lymphocyte 73%). Chest CT showed mildly increased bilateral linear opacities. The patient was given supportive treatment and recovered gradually. Another 30-h-old neonate, born to an infected mother, initially presented with respiratory distress without fever, and later was confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2, according to a news report by China News Service.

If the disease went further extension without being efficiently contained, the outbreak might go into an explosion stage, when the school transmission mixed with a wider community spread could occur (Fig. 1B). Children at that stage can further become the main spreader of SARS-CoV-2 because their infection is usually mild. At this stage, temporary school closure may be necessary to contain the spread of the infection. The situation is similar to what we have seen in influenza outbreak, where school children are the driver for the dissemination of influenza virus either in the household or in the community. In Fig. 1A, 398 pediatric cases outside the Hubei province have been identified before February 10, 2020, indicating that the epidemic in China has spread widely in many regions in addition to the Hubei province and reached the explosion stage. The positive correlation of the accumulated cases from adult and pediatric populations strongly supports the transmission dynamics of pediatric patients we described (Fig. 1B).

Infected children may be asymptomatic or have fever, dry cough and fatigue; some patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Most infected children have mild clinical manifestations and usually have a good prognosis. Usually they recover within 1–2 weeks after the onset of the disease.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Having said that, we noticed that there were 2 severe pediatric cases in Wuhan. A 1-year-old infant with severe COVID-19 was reported by Chen et al. in Wuhan Children's Hospital.12 The child presented with fever and respiratory distress for 1 day and vomiting and diarrhea for 6 days.12 Chest radiography and CT showed pneumonia, and he was admitted to intensive care unit and intubated immediately. After the treatment, including assisted ventilation and continuous venovenous hemofiltration, he recovered gradually. So far, there has been no mortality among the children with COVID-19 in China.

Adults with COVID-19 usually showed a significant or progressive decrease in the absolute number of peripheral blood lymphocytes at the early stage of the disease. T lymphocyte subsets showed a decrease in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an early and reliable indicator for the development of severe COVID-19, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 can consume lymphocytes, which may also be an important reason for the virus to proliferate and spread in the early stage of the disease.13 Severe cases in adults usually progress 7–10 days after the onset of disease, likely due to rapid virus replication, inflammatory cell infiltration, and an increased proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine response, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a fatal acute lung injury.13 In children, however, white blood cell count and absolute lymphocyte count were mostly normal, and no lymphocyte depletion occurred, suggesting less immune dysfunction after the SARS-CoV-2 infection.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 On the other hand, the mild disease in children may be related to trained immunity. Trained immunity, as a new immune model, refers to the use of certain vaccines such as Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) to train innate immunity to generate immune memory.14 BCG has been proved to provide nonspecific protection of mice against influenza virus infection probably by the induction of trained immunity.14 Most, if not all, of the infants received regular immunizations, including BCG, in China and other Asian countries, and it is well known that influenza can cause more ARDS in the adults, yet very less in children.

In conclusion, understanding the role of pediatric population in the transmission dynamics of the outbreak is important, as children may become a significant spreader at the explosion stage of the outbreak. Further studies to unveil why sick children have a milder form of disease may help to the future development of immunotherapy and vaccines for the SARS-CoV-2.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Health Commission of Hubei Province, Wuhan, Hubei National Health commission of the People's Republic of China. http://wjw.hubei.gov.cnhttp://www.nhc.gov.cn [Beijing, People’s Republic of China (in Chinese)]

- 2.Lau J.T.F., Lau M., Kim J.H., Tsui H.Y., Tsang T., Wong T.W. Probable secondary infections in households of SARS patients in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:235–243. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfig J.A., Assiri A., AlRabiah F.A., Al Hajjar S., Albarrak A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:904–906. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y.P. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2020;41:145–151. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. Coronavirus infections ‒ More than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y.H., Lin D.J., Xiao M.F., Wang J.C., Wei Y., Lei Z.X. 2019-novel coronavirus infection in a three-month-old baby. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zh. 2020;58:E006. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.0006. [Article in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei M., Yuan J., Liu Y., Fu T., Yu X., Zhang Z.J. Novel coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai J.H., Wang X.S., Ge Y.L., Xia A.M., Chang H.L., Tian H. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children in Shanghai. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:E002. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.0002. [Article in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng L.K., Tao X.W., Yuan W.H., Wang J., Liu X., Liu Z.S. First case of neonate infected with novel coronavirus pneumonia in China. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:E009. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.0009. [Article in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen F., Liu Z.S., Zhang F.R., Xiong R.H., Chen Y., Cheng X.F. Frist case of severe childhood novel coronavirus pneumonia in China. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:E005. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.0005. [Article in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J., Liu Y., Xiang P., Pu L., Xiong H., Li C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts severe illness patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the early stage. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.10.20021584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Netea M.G., Schlitzer A., Placek K., Joosten L.A.B., Schultze J.L. Innate and adaptive immune memory: an evolutionary continuum in the host's response to pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]