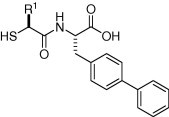

Graphical abstract

Screening of a metalloprotease library led to the identification of a thiol-based dual ACE/NEP inhibitor as a potent ACE2 inhibitor. Modifications of the P1 benzyl moiety led to improvements in ACE2 potency as well as to increased selectivity versus ACE and NEP.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, Metalloproteases, Protease inhibitors, Thiols

Abstract

Screening of a metalloprotease library led to the identification of a thiol-based dual ACE/NEP inhibitor as a potent ACE2 inhibitor. Modifications of the P1 benzyl moiety led to improvements in ACE2 potency as well as to increased selectivity versus ACE and NEP.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a recently identified clan MA, family M2 monocarboxypeptidase with highest homology to the dicarboxypeptidase angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE, EC 3.4.15.1).1, 2 This membrane-associated and secreted metalloprotease is expressed in heart, kidney, testes, intestine, and lung, and has been implicated in cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, obesity, and lung disease.3, 4, 5

ACE2 processes angiotensin I and the AT1 and AT2 receptor agonist angiotensin II to produce angiotensin (1–9) and the mas receptor agonist angiotensin (1–7), respectively, but its exact role in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) needs to be clarified. One group has reported that C57BL/6 ACE2 (−/−) mice exhibit a severe reduction in cardiac contractility, which is rescued in the ACE (−/−)/ACE2 (−/−) double knockout.6 In contrast, another group has disclosed that ACE2 (−/−) mice of 129/SvEv, C57BL/6, and mixed background do not exhibit cardiac contractility defects, but have increased susceptibility to angiotensin II-induced hypertension.7 While, a third group has revealed that male ACE (−/Y) mice are more susceptible to heart failure and death after transverse aortic constriction than their normal littermates.8 Supporting a role for ACE2 in cardiac function, transgenic mice overexpressing ACE2 in the heart have lower mean arterial pressure with rare focal myocyte vacuolization, myofibril splaying, and nuclear enlargement. Many of these mice develop terminal ventricular fibrillation with lethal arrhythmias.9

Furthermore, male ACE2 (−/Y) mice, but not female ACE2 (−/−) mice, also accumulate fibrillar collagen in the renal glomerular mesangium, leading to development of glomerulosclerosis of the kidneys.10 In addition, ACE2 (−/−) mice exhibit lower body weights than wild type mice with reduced fat mass.11 Moreover, ACE2 is also utilized by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus as the receptor for infection.12 ACE2 (−/−) mice are resistant to SARS corona virus infection.13 Finally, ACE2 (−/−) mice have enhanced vascular permeability, increased lung edema, and worsened lung function in several murine acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) models.14 With the many potential functions of ACE2, small molecule inhibitors of this enzyme could be utilized to help further define the physiological roles of this protease.

ACE2 belongs to the zinc metalloprotease family and it has been reported that classical ACE inhibitors such as captopril and lisinopril do not attenuate ACE2 enzyme activity. As part of a strategy to discover lead molecules for an ACE2 inhibitor program, a directed screen of ACE2 versus a set of metalloprotease inhibitors from the GlaxoSmithKline compound collection was performed. Surprisingly, although confirming that classical ACE inhibitors like captopril were inactive in the screen, the thiol acid 1a was identified as a potent ACE2 inhibitor (K i App = 86 nM).15 This biphenyl analog 1a is a known dual ACE and M13 metalloprotease neutral endopeptidase (neprilysin, NEP, EC 3.4.24.11) inhibitor (ACE K i App = 30 nM, NEP K i App = 1.1 nM).16 It also inhibits the M14 metalloprotease carboxypeptidase A1 (CpA, EC 3.4.17.1, K i App = 1,200 nM). Speculating that the thiol functioned as a binding group for the active site zinc and that the carboxylic acid served as a recognition element for the enzyme’s monocarboxypeptidase activity, the benzyl and methylene p-biphenyl moieties were surmised to be the P1 and substituents. With this premise, the structure activity relationships of the P1 position of the lead inhibitor were explored with the goal of improving potency and reducing ACE and NEP inhibitory activity.

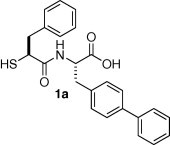

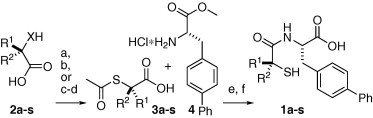

The thiol analogs 1a–1s were prepared as depicted in Scheme 1 . The acids 3a–3s were activated in situ via the carbodiimide, converted into the activated esters with the aza-hydroxybenzotriazole, and then coupled to the amine hydrochloride 4 to produce the fully protected amides. Subsequent hydrolysis of the methyl ester, as well as the thioacetate, with lithium hydroxide afforded the thiol acids 1a–1s.17

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 2c and 2e, X S, AcCl, NEt3, dioxane, 0 °C to rt, 15–37%; (b) 2k, 2m, and 2n, X O, AcSH, DIAD, PPh3, THF, 0 °C to rt, 24–67%; (c) 2a–2b, 2d, 2f–2j, 2l, 2o–2s, X NH, HBr, NaNO2, H2O, 0 °C, 25–80%; (d) AcS−K+, DMF, 0 °C to rt, 11–72%; (e) EDC, HOAt, i-Pr2NEt, CH2Cl2, 48–96%; (f) LiOH·H2O, THF, H2O, 30–94%.

The thiol acids 3a–3s were produced by three different routes. Acids 3c and 3e were prepared by reaction of the commercially available thiols 2c and 2e (X S) with acetyl chloride. In contrast, the acids 3k, 3m, and 3n were produced from the alcohols 2k, 2m, and 2n (X O) via the Mitsunobu reaction with thioacetic acid.18 Alternatively, the acids 3a–3b, 3d, 3f–3j, 3l, and 3o–3s were synthesized from the commercially available amino acids 2a–2b, 2d, 2f–2j, 2l, and 2o–2s (X NH), by diazotization of the amines to afford the bromides, then subsequent displacement of the bromides, by potassium thioacetate, with stereochemical inversion. Some stereochemical erosion, presumably resulting from formation of the α-lactone before nucleophilic trapping, resulted during the Mitsunobu and diazotization reaction steps, but after coupling with the amine 4, the minor diastereomer could be removed via chromatography.

The structure/activity relationships of P1 analogs are depicted in Table 1 . The (R) isomer 1b derived from l-phenylalanine displays the P1 benzyl substituent in the unnatural configuration. This orientation of the P1 substituent was detrimental to the ACE2 inhibitory activity of diastereomer 1b (K i App = 1400 nM) as well as that of ACE (K i App = 520 nM). This loss in inhibition is not surprising, since nature has evolved proteases to recognize the natural configuration of physiological peptide substrates. In contrast, NEP (K i App = 1.3 nM) accommodated the alternate configuration with no loss in potency.

Table 1.

Inhibition of human ACE2, ACE, NEP, and CpA

| # | R1 | R2 | ACE2 Ki Appa (nM) | ACE Ki Appb (nM) | NEP Ki Appc (nM) | CpA Ki Appd (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | CH2Ph | H | 86 | 30 | 1.1 | 1200 |

| 1b | H | CH2Ph | 1400 | 520 | 1.3 | 310 |

| 1c | H | H | 320 | 16 | 13 | 1700 |

| 1d | Me | H | 6.9 | 21 | 23 | 14,000 |

| 1e | Me | Me | 2300 | 3400 | 730 | >50,000 |

| 1f | Et | H | 1.4 | 8.6 | 0.80 | 9,300 |

| 1g | n-Bu | H | 1.8 | 9.3 | 1.2 | 8900 |

| 1h | i-Pr | H | 1.5 | 200 | 13 | 17,000 |

| 1i | (R)-s-Bu | H | 1.5 | 490 | 27 | 11,000 |

| 1j | (S)-s-Bu | H | 1.6 | 200 | 2.4 | 15,000 |

| 1k | Cyb | H | 2.4 | 620 | 5.4 | 12,000 |

| 1l | Cyp | H | 1.8 | 700 | 38 | 12,000 |

| 1m | Cyh | H | 65 | 13,000 | 1300 | 12,000 |

| 1n | Ph | H | 84 | >10,000 | 410 | >50,000 |

| 1o | i-Bu | H | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0.28 | 11,000 |

| 1p | CH2t-Bu | H | 7.1 | 2,700 | 2.6 | 22,000 |

| 1q | CH2Cyh | H | 420 | 840 | 130 | 17,000 |

| 1r | CH2β-Np | H | 550 | 210 | 140 | 32,000 |

| 1s | (CH2)2Ph | H | 860 | 93 | 2.6 | 5,000 |

Inhibition of recombinant human ACE2 activity in a fluorescence assay using 0.4 nM ACE2, 30 μM MCA-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-Ala-Pro-Lys(DNP)-OH as substrate in 1 μM Zn(OAc)2, 100 μM TCEP, 50 mM Hepes, 300 μM CHAPS, and 300 mM NaCl at pH = 7.5. The average percent coefficient of variance for the Ki App values was 45%.

Inhibition of recombinant human ACE activity in a fluorescence assay using 0.5 nM ACE, 10 μM MCA-Ala-Ser-Asp-Lys-Dap(DNP)-OH as substrate in 1 μM Zn(OAc)2, 100 μM TCEP, 50 mM Hepes, 300 μM CHAPS, and 300 mM NaCl at pH = 7.5. The average percent coefficient of variance for the Ki App values was 58%.

Inhibition of recombinant human NEP activity in a fluorescence assay using 0.15 nM NEP, 2 μM FAM-Gly-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Phe-Ala-Arg-Lys(TAMRA)-NH2 as substrate in 1 μM Zn(OAc)2, 100 μM TCEP, 50 mM Hepes, 300 μM CHAPS, and 300 mM NaCl at pH = 7.5. The average percent coefficient of variance for the Ki App values was 43%.

Inhibition of recombinant human CpA activity in a fluorescence assay using 37 nM CpA, 30 μM Abz-Gly-Gly-Nph-OH as substrate in 1 μM Zn(OAc)2, 100 μM TCEP, 50 mM Hepes, 300 μM CHAPS, and 300 mM NaCl at pH = 7.5. The average percent coefficient of variance for the Ki App values was 38%.

Complete removal of the P1 moiety caused a modest loss in inhibitory potency versus ACE2 (H, K i App = 320 nM). This decrease in potency could arise from reduced van der Waals interactions due to the lack of a P1 substituent, the increased entropic cost for the inhibitor to bind to the protease given the inhibitor’s increased rotational freedom, or a combination of these factors. In contrast to the D-isomer 1b, the ACE activity (K i App = 16 nM) of the glycine-like analog 1c was not affected by elimination of the P1 element, while NEP potency (K i App = 13 nM) of 1c decreased by over an order of magnitude.

The alanine-derived analog 1d (Me, K i App = 6.9 nM) decreases rotational freedom and was an even more potent ACE2 inhibitor than the starting lead 1a, while increasing selectivity versus both ACE (K i App = 21 nM) and NEP (K i App = 23 nM). In contrast, the geminal dimethyl analog 1e (ACE2 K i App = 2300 nM) decreased inhibitory potency versus not only ACE2, but also ACE (K i App = 3,400 nM) and NEP (K i App = 730 nM). Similar to the methyl analog 1d, the linear P1 ethyl and n-butyl analogs 1f (Et, K i App = 1.4 nM) and 1g (n-Bu, K i App = 1.8 nM) were also potent ACE2 inhibitors, but these extensions in P1 also increased activity versus ACE (1f K i App = 8.6 nM, 1g K i App = 9.3 nM) and even more so versus NEP (1f K i App = 0.80 nM, 1g K i App = 1.2 nM).

With the hope of improving the selectivity of these thiol-based inhibitors versus ACE and NEP, the effect of branching along the P1 side chain of this inhibitor class was explored. Branching along the P1 chain was well tolerated in the S1 subsite of ACE2. The α-branched iso-propyl 1h (i-Pr, K i App = 1.5 nM), (R)-sec-butyl 1i ((R)-s-Bu, K i App = 1.5 nM), (S)-sec-butyl 1j ((S)-s-Bu, K i App = 1.6 nM), cyclobutyl 1k (Cyb, K i App = 2.4 nM), and cyclopentyl 1l (Cyp, K i App = 1.8 nM) analogs and the β-branched iso-butyl 1o (i-Bu, K i App = 1.4 nM) and neo-pentyl 1p (CH2 t-Bu, K i App = 7.1 nM) analogs maintained their ACE2 inhibition. Only the bulkier branched analogs, like the α-branched cyclohexyl 1m (Cyh, K i App = 65 nM) and phenyl 1n (Ph, K i App = 84 nM), the β-branched methylene cyclohexyl 1q (CH2Cyh, K i App = 420 nM) and methylene β-naphthyl 1r (CH2β-Np, K i App = 550 nM), and the γ-branched ethylene phenyl 1s ((CH2)2Ph, K i App = 860 nM), were too large to be accommodated by the ACE2 S1 subsite.

In contrast, α-branching of the P1 moiety was poorly tolerated by the ACE S1 subsite, resulting in substantial decreases in ACE inhibitory activity for the α-branched iso-propyl 1h (K i App = 200 nM), (R)-sec-butyl 1i (K i App = 490 nM), (S)-sec-butyl 1j (K i App = 200 nM), cyclobutyl 1k (K i App = 620 nM), cyclopentyl 1l (K i App = 700 nM), cyclohexyl 1m (K i App = 13,000 nM), and phenyl 1n (K i App = >10,000 nM) analogs. The S1 subsite of NEP is more accepting of α-branching in P1 substituents than the ACE enzyme, but less liberal than ACE2. The α-branched iso-propyl 1h (K i App = 13 nM), (R)-sec-butyl 1i (K i App = 27 nM), (S)-sec-butyl 1j (K i App = 2.4 nM), cyclobutyl 1k (K i App = 5.4 nM), cyclopentyl 1l (K i App = 38 nM), cyclohexyl 1m (K i App = 1300 nM), and phenyl 1n (K i App = 410 nM) analogs lost some inhibitory activity versus NEP relative to the ethyl analog 1f (K i App = 0.80 nM). Thus, α-branching at the P1 group enhanced selectivity for ACE2 protease inhibition relative to ACE and NEP. The (R)-sec-butyl analog 1i (K i App = 1.5 nM) has 330-fold selectivity versus ACE and 18-fold selectivity versus NEP, while the cyclopentyl 1l (K i App = 1.8 nM) has 390-fold selectivity versus ACE and 21-fold selectivity versus NEP.

In comparison to α-branching, both ACE and NEP S1 subsites were more permissive to β-branching in P1 groups. Thus, the iso-butyl 1o analog is not only a potent ACE2 inhibitor (K i App = 1.4 nM), but also a low nanomolar ACE (K i App = 3.2 nM) and subnanomolar NEP inhibitor (K i App = 0.28 nM). ACE is less tolerant of bulky β-branching, with the neo-pentyl 1p analog exhibiting potent dual ACE2 (K i App = 7.1 nM) and NEP (K i App = 2.6 nM) inhibition with good selectivity over ACE (K i App = 2700 nM). Larger β-branched substituents like the methylene cyclohexyl 1q (ACE2 K i App = 420 nM, ACE K i App = 840 nM, NEP K i App = 130 nM) and methylene β-naphthyl 1r (ACE2 K i App = 550 nM, ACE K i App = 210 nM, NEP K i App = 140 nM) attenuate inhibitory activity at all three enzymes. Finally, as the ethylene phenyl analog 1 s shows, like ACE2 (K i App = 860 nM), ACE (K i App = 93 nM) was less tolerant of γ-branching in P1 groups, while NEP (K i App = 2.6 nM) accepted it. None of these thiol-based inhibitors was a potent inhibitor of CpA.

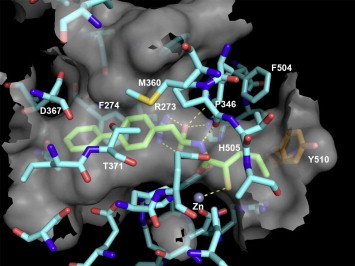

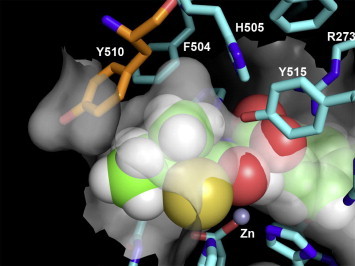

A model of the thiol 1i 19, 20 docked into the active site of ACE2 based on the recent X-ray crystal structure21 is shown in Figure 1 . It provides insight into the SAR of the thiol series. In addition to binding to the imidazole nitrogens of 374His and 378His and the carboxylate of 402Glu, the active site zinc coordinates the thiol of the inhibitor. Also, the terminal carboxylate of the inhibitor forms electrostatic interactions with the guanidine of 273Arg and accepts hydrogen bonds from the imidazoles of 345His and 505His. Moreover, the carbonyl of 346Pro accepts a hydrogen bond from the amide nitrogen of the inhibitor, while the amide carbonyl is stabilized by a hydrogen bond to 515Tyr. Furthermore, the methylene biphenyl substituent of 1i forms significant lipophilic interactions with the quite large channel composed of the lengthwise canal between the two subdomains, including residues 274Phe, 276Thr, 346Pro, 367Asp, 370Leu, 371Thr, and 374His. This biphenyl substituent is hypothesized to occupy a different part of this large pocket than the carboxyl inhibitor co-crystallized in 1R4L. The P1 (R)-sec-butyl group of the inhibitor forms van der Waals interactions with the S1 pocket composed of 347Thr, 504Phe, 510Tyr, and 514Arg. As shown in the close-up of the S1 subsite depicted in Figure 2 , 510Tyr forms part of a pocket which the α-branched methyl of the P1 (R)-sec-butyl group occupies. Larger substituents are disfavored as they would require movement of the phenol side chain of 510Tyr. Thus, this model agrees with the SAR, since the S1 subsite can tolerate cyclobutyl and cyclopentyl substituents, but is less accepting of a cyclohexyl group.

Figure 1.

A model of the thiol compound 1i bound to the active site of ACE2 based on a X-ray co-crystal structure of a carboxylate inhibitor bound to ACE2 (PDB code 1R4L). The ACE2 carbons are colored cyan with inhibitor 1i carbons colored green. The semi-transparent gray surface represents the molecular surface, while hydrogen bonds are depicted as yellow dashed lines. Several residues were removed for visual clarity. This figure was generated using PYMOL version 1.0 (Delano Scientific, www.pymol.org).

Figure 2.

A close up of the P1 pocket of the model of the thiol compound 1i bound to the active site of ACE2 based on a X-ray co-crystal structure (PDB code 1R4L). The ACE2 carbons are colored cyan with inhibitor 1i carbons colored green. 510Tyr is colored in orange to highlight its putative role in the selectivity of 1i. The semi-transparent gray surface represents the molecular surface. This figure was generated using PYMOL version 1.00 (Delano Scientific, www.pymol.org).

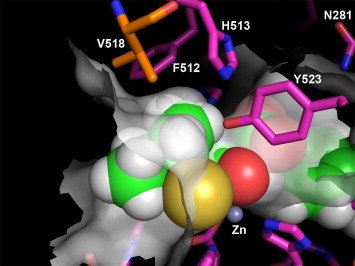

A model of the inhibitor 1i 19, 20 docked into the active site of ACE, focusing on the S1 subsite, based on the X-ray structure of lisinopril with ACE,22 is shown in Figure 3 . From the model, it is apparent that the methyl group of the (R)-sec-butyl P1 moiety of inhibitor 1i bumps into the enzyme, helping explain the 330-fold selectivity for ACE2 versus ACE. The branching nature of 518Val (atom CG1) makes this portion of the S1 pocket smaller than in ACE2. 518Val is the homologous residue in ACE to 510Tyr in ACE2. This 510Tyr to 518Val substitution from ACE2 to ACE and resulting alteration of the S1 pocket volume helps explain the reduced ability of ACE to accommodate α-branching in P1 substituents.

Figure 3.

A model of the thiol compound 1i bound to the active site of ACE using the X-ray co-crystal structure of ACE and lisinopril (PDB code 1O86). The ACE carbons are colored magenta with inhibitor 1i carbons colored green. 518Val is colored orange to highlight its hypothesized role in the selectivity of 1i. The semi-transparent gray surface represents the molecular surface. This figure was generated using PYMOL version 1.00 (Delano Scientific, www.pymol.org).

Although X-ray structures of NEP co-crystallized with a thiol-based inhibitor (PDB code 1Y8J)23 and an analog with a bi-phenyl moiety (PDB code 1R1H)24 are available, as NEP belongs to a different metalloprotease family (M13 vs M2), no reasonable model of these thiol inhibitors bound to NEP could be determined to help explain the increase in NEP selectivity of α-branched P1 analogs. Likely protein movement to accommodate potent NEP inhibitors like 1o is required. The movement of multiple amino acid residues in proteins is difficult to predict accurately.

In summary, a series of α-thiol amide-based inhibitors of ACE2 with varied substituents at the P1 position were synthesized. Inhibitors containing linear alkyl P1 moieties were some of the more potent analogs in the ACE2 enzymatic assay. The smaller α-branched P1 substituents, exemplified by inhibitors 1i and 1l, maintained similar potencies, and increased selectivity versus ACE and NEP. Information gained from these studies has proven to be useful in the design of other ACE2 inhibitors. These inhibitors will be reported in due course. Furthermore, a potent pan ACE/ACE2/NEP inhibitor 1o and a potent dual ACE2/NEP inhibitor 1p have been identified. These tools may prove useful in further defining the roles these proteases play in the RAS cascade.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Rob I. West for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.048.

Supplementary data

References and notes

- 1.Donoghue M., Hsieh F., Baronas E., Godbout K., Gosselin M., Stagliano N., Donovan M., Woolf B., Robison K., Jeyaseelan R., Breitbart R.E., Acton S. Circ. Res. 2000;87:e1. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tipnis S.R., Hooper N.M., Hyde R., Karran E., Christie G., Turner A.J. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danilczyk U., Penninger J.M. Circ. Res. 2006;98:463. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205761.22353.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuba K., Imai Y., Penninger J.M. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 2006;6:271. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tallant E.A., Ferrario C.M., Gallagher P.E. Future Cardiol. 2006;2:335. doi: 10.2217/14796678.2.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crackower M.A., Sarao R., Oudit G.Y., Yagil C., Kozieradzki I., Scanga S.E., Oliveira-dos-Santos A.J., da Costa J., Zhang L., Pei Y., Scholey J., Ferrario C.M., Manoukian A.S., Chappell M.C., Backx P.H., Yagil Y., Penninger J.M. Nature. 2002;417:822. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurley S.B., Allred A., Le T.H., Griffiths R., Mao L., Philip N., Haystead T.A., Donoghue M., Breitbart R.E., Acton S.L., Rockman H.A., Coffman T.M. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2218. doi: 10.1172/JCI16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto K., Ohishi M., Katsuya T., Ito N., Ikushima M., Kaibe M., Tatara Y., Shiota A., Sugano S., Takeda S., Rakugi H., Ogihara T. Hypertension. 2006;47:718. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205833.89478.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoghue M., Wakimoto H., Maguire C.T., Acton S., Hales P., Stagliano N., Fairchild-Huntress V., Xu J., Lorenz J.N., Kadambi V., Berul C.I., Breitbart R.E. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:1043. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oudit G.Y., Herzenberg A.M., Kassiri Z., Wong D., Reich H., Khokha R., Crackower M.A., Backx P.H., Penninger J.M., Scholey J.W. Am. J. Path. 2006;168:1808. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acton, S. L.; Ocain, T. D.; Gould, A. E.; Dales, N. A.; Guan, B.; Brown, J. A.; Patane, M.; Kadambi, V. J.; Solomon, M.; Stricker-Krongrad, A.; PCT Int. Appl. WO 039997, 2002; Chem. Abstr.2002,136, 402027.

- 12.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H., Farzan M. Nature. 2003;426:450. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W., Bao L., Zhang B., Liu G., Wang Z., Chappell M., Liu Y., Zheng D., Leibbrandt A., Wada T., Slutsky A.S., Liu D., Qin C., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S., Huan Y., Guo F., Guan B., Yang P., Sarao R., Wada T., Leong-Poi H., Crackower M.A., Fukamizu A., Hui C.-C., Hein L., Uhlig S., Slutsky A.S., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. Nature. 2005;436:112. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deaton D.N., Gao E.N., Graham K.P., Gross J.W., Miller A.B., Strelow J.M. In: 5th General Meeting of the International Proteolysis Society. Sotiropoulou G., Pampalakis G., Arampatzidou M., editors. International Proteolysis Society; Patras, Greece: 2007. p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhagwat S.S., Fink C.A., Gude C., Chan K., Qiao Y., Sakane Y., Berry C., Ghai R.D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995;5:735. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hydrolyses were performed under an argon atmosphere. When hydrolyses were carried out with reactions open to the atmosphere, varying amounts of disulfide products were isolated, likely from aerobic oxidation. The enzyme assays contain a reducing agent, tris-(2-chloroethyl)-phosphate (TCEP), to prevent oxidation of the thiols to disulfides during the assays. Dilutions of 10 mM stock solutions of the thiols 1a–1s to final assay concentrations were done with 50% aqueous acetonitrile just prior to protease inhibition studies. Under these standard conditions, both the thiols and their corresponding disulfides showed enzyme inhibitory activity. Presumably, the disulfides were reduced to their corresponding thiols by TCEP during the pre-incubation period, before substrates were added. In contrast, if the assays were performed without TCEP, the disulfides were completely inactive, while the potencies of the thiols were attenuated, probably because of partial aerobic oxidation to their corresponding disulfides during the pre-incubation period.

- 18.Alcohols 2m and 2n are commercially available. Alcohol 2k was prepared from cyclobutane methanol in three steps. First, oxidation of the alcohol with pyridinium chlorochromate afforded the aldehyde. Then, reaction of the aldehyde with trimethylsilyl cyanide and N-methyl morpholine N-oxide provided the silyl protected cyanohydrin. Finally, hydrochloric acid catalyzed hydrolysis of the cyanohydrin yielded the hydroxyacid 2k.

- 19.Lambert M.H. In: Practical Application of Computer-Aided Drug Design. Charifson P.S., editor. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The ‘grow’ algorithm within the MVP program was used to dock the inhibitor into the active site beginning from the carboxylic acid group.

- 21.Towler P., Staker B., Prasad S.G., Menon S., Tang J., Parsons T., Ryan D., Fisher M., Williams D., Dales N.A., Patane M.A., Pantoliano M.W. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natesh R., Schwager S.L.U., Sturrock E.D., Acharya K.R. Nature. 2003;421:551. doi: 10.1038/nature01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahli S., Frank B., Schweizer W.B., Diederich F., Blum-Kaelin D., Aebi J.D., Boehm H.-J., Oefner C., Dale G.E. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2005;88:731. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oefner C., Roques B.P., Fournie-Zaluski M.C., Dale G.E. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:392. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903027410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.