To the Editor,

Pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection has been identified as the cause of a widespread outbreak of febrile respiratory tract infection. On June 11, 2009, the World Health Organization raised its pandemic alert to the highest level, phase 6.

The H1N1 influenza virus infection rapidly spread all over Japan after the first case was confirmed in Kobe, Japan, on May 16. The outbreak of this virus had a great impact on the Japanese society. There was a shortage in masks and antiseptic [1], [2]. More than 4800 schools had been closed, medical services were swamped, many companies were forced into bankruptcy, and the stock market price declined [3], [4]. Kobe suffered the most severe impact of the H1N1 influenza in Japan.

Previous studies on severe acute respiratory syndrome [5] and the seasonal influenza [6] reported that emergency departments (EDs) were overcrowded in the epidemic and that the number of ED ambulance diversion increased. Emergency medical service (EMS) was greatly influenced by the epidemic, whereas it remains unknown whether EMS was influenced by the H1N1 influenza virus pandemic.

In Japan, the emergency paramedics are allowed to triage patients. When the emergency paramedics contact with patients, they negotiate with hospitalists to find a hospital where physicians can provide the medical support. To investigate the impacts of the H1N1 influenza pandemic on EMS, we studied the situation of EMS during the epidemic provided by the emergency paramedics.

Using an ambulance dispatch data of the Fire Prevention Bureau of Kobe, we extracted data on patients with fever higher than 37.5°C who called an ambulance between April 16 and June 16. We examined the following variables including the time between EMS call and arrival at hospital, that between arrival to the site and the departure from it, and the number of times of negotiation by paramedics with hospitalists for patients' acceptance.

To evaluate the impact of the pandemic on the EMS system, we studied the longitudinal changes in these variables during the pandemic. We defined the period from April 16 to May 16 as the preepidemic stage and that from May 17 to June 16th as the postepidemic stage. We compared these variables in preepidemic stage with those in postepidemic stage.

Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis, and P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

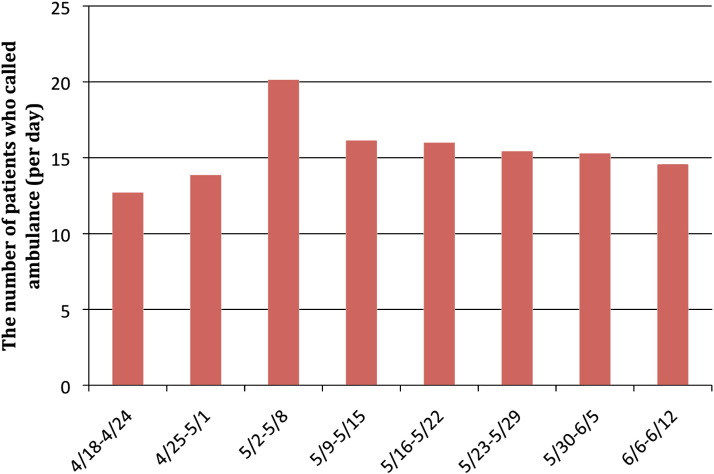

An ambulance was called by 961 patients during the study period, 469 and 492 patients in the preepidemic and postepidemic periods, respectively (Fig. 1 ). There was no significant difference between the 2 periods (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The number of febrile patients who called an ambulance remained unchanged during the study period.

Table 1.

The interval between EMS call and arrival at hospital and the sojourn time at the site were significantly longer in the postepidemic period than in the preepidemic period

| preepidemic |

postepidemic |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average (SD) | Average (SD) | ||

| No. of patients who called ambulance (/d) | 16.17 (5.015) | 15.87 (3.748) | .794a |

| No. of hospitals with which the paramedics negotiated for patients' transfer (/patient) | 1.35 (0.960) | 1.34 (0.902) | .778a |

| Mean (range) | Mean (range) |

P |

|

| The interval between EMS call and arrival at hospital (min) | 28.8 (10.2-97.8) | 31.3 (9.40-128) | <.001b |

| The sojourn time at the site (min.) | 14.0 (4.00-70.0) | 17.0 (1.00-86.0) | <.001b |

t test.

Mann-Whitney U test.

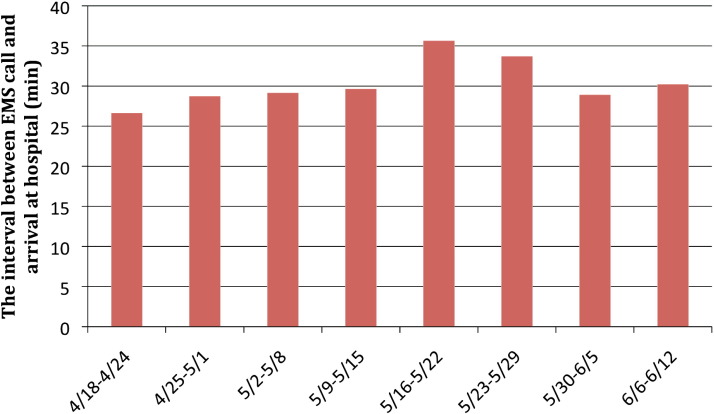

The interval between EMS call and arrival at hospital was significantly longer in the postepidemic period (mean, 28.8 minutes; range, 10.2-97.8 minutes) than in the preepidemic period (mean, 31.3 minutes; range, 9.4-128 minutes) (P < .001) (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

The interval between EMS call and arrival at hospital was significantly longer in the postepidemic period than in the preepidemic period.

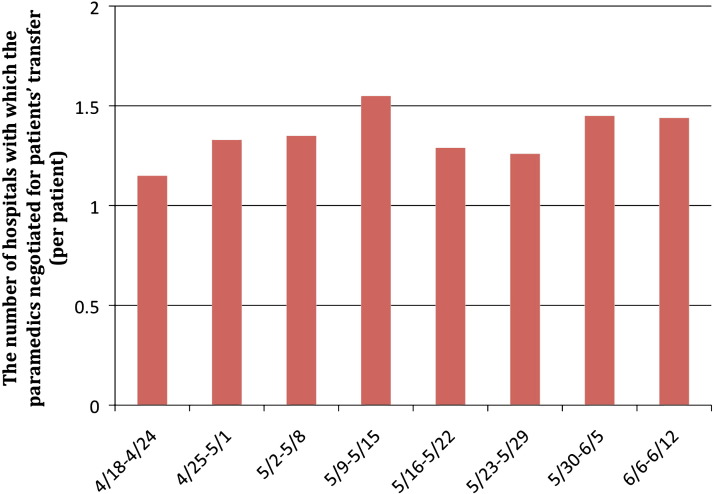

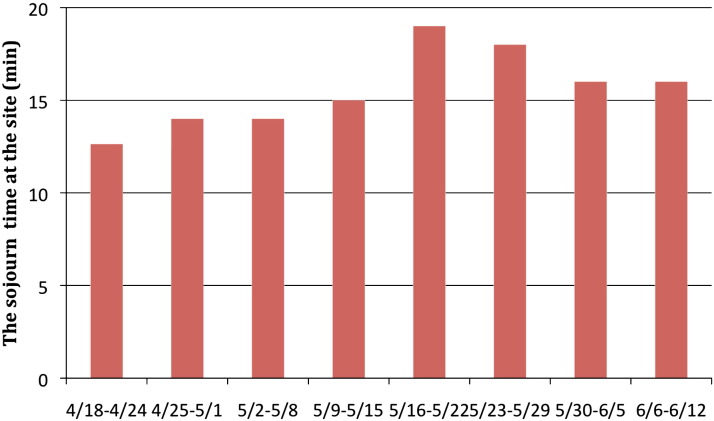

The number of hospitals with which the paramedics negotiated for patients' transfer was comparable between the 2 periods (Fig. 3 and Table 1), whereas the sojourn time at the site was prolonged in the postepidemic period (mean, 17.0 minutes; range, 4.0-70 minutes) compared with the preepidemic period (mean, 14.0 minutes; range, 1.0-86 minutes). The difference was statistically significant (P < .001) (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Fig. 3.

The number of hospitals with which the paramedics negotiated for patients' transfer was comparable between the 2 periods.

Fig. 4.

The sojourn time at the site was prolonged in the postepidemic period compared with the preepidemic period.

This study showed that H1N1 influenza pandemic did not have a great impact on the EMS system of Kobe.

Interestingly, the number of febrile patients who called an ambulance remained unchanged during the study period. This finding was in contrast to the situation in the EDs and the clinics, which were overcrowded with patients who had been scared by the repetitive press reports. Patients with H1N1 influenza occasionally developed severe manifestations. It is reasonable to assume that most patients with suspected H1N1 influenza infection might have visited clinic at its early stages on foot.

It is interesting that paramedics needed an extra time of 3 minutes to triage patients. Considering that the number of hospitals with which the paramedics negotiated for patients' transfer was comparable between the 2 periods, this extra time was required to provide the hospitalists with precise information on febrile patients, including symptoms and records of oversea travel. This finding is consistent with the fact that paramedics were required to fill in a form about patients' information during the study period. It is unlikely that hospitalists refused patients with possible H1N1 influenza infection because of fears of in-hospital spread of the infection.

This is a small-sized retrospective study, and unrecognized bias might have existed. Nationwide survey will be necessary to evaluate the true impact of H1N1 influenza pandemic on EMS system. However, it is likely that H1N1 influenza pandemic did not have a great impact on supply and demand of EMS system. H5N1 influenza virus is another concern, although we should be careful in applying the results of this study to predicting its influence on the EMS. There are considerable differences in the virulence between the 2 types of influenza viruses.

References

- 1.Spread of swine flu puts Japan in crisis mode. NY Times. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masks, gargles enjoying surge in popularity. Jpn Times Online. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flu virus starts to take toll on businesses. Travel industry seen facing biggest risk. Jpn Times Online. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flu scare could harm economy. Jpn Times Online. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heiber M, Lou WY. Effect of the SARS outbreak on visits to a community hospital emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2006;8(5):323–328. doi: 10.1017/s148180350001397x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menec VH, Black C, MacWilliam L, Aoki FY. The impact of influenza-associated respiratory illnesses on hospitalizations, physician visits, emergency room visits, and mortality. Can J Public Health. 2003;94(1):59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03405054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]