Abstract

Canine parvovirus (CPV) is an important pathogen in domestic dogs, and the original antigenic types CPV-2 and its variants, CPV-2a, 2b and 2c, are prevalent worldwide. A multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR method was developed for the detection and differentiation of four antigenic types of CPV. A set of primers and probes, CPV-305F/CPV-305R and CPV-2-305P (for CPV-2)/CPV-2a-305P (for CPV-2a, 2b and 2c), was able to differentiate CPV-2 and its variants (CPV-2a, 2b and 2c). Another set of primers and probes, CPV-426F/CPV-426R and CPV-2-426P (for CPV-2 and 2a)/CPV-2b-426P (for CPV-2b)/CPV-2c-426P (for CPV-2c), was able to differentiate CPV-2a (2), CPV-2b, and CPV-2c. With these primers and probes, the multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR assay detected effectively and differentiated CPV-2, 2a, 2b and 2c by two separate real-time PCRs. No cross reactivity was observed with canine distemper virus, canine adenovirus, and canine coronavirus. The detection limit of the assay is 101 genome copies/μL for CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and 102 copies/μL for CPV-2c. The multiplex real-time PCR has 100% agreement with DNA sequencing. We provide a sensitive assay that simultaneously detects and differentiate four antigenic types of CPV and the method was also used for quantification of CPVs viral genome.

Keywords: Canine parvovirus, Multiplex real-time PCR, Detection, Differentiation, Antigenic types

Highlights

-

•

The Multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR can simultaneously detect and differentiate four antigenic types of CPV.

-

•

The method is suit for using in detection of CPVs in China.

-

•

The method showed a high specificity and sensitivity.

-

•

The method was also used for quantification of CPVs viral genome.

1. Introduction

Canine parvovirus (CPV) is an important pathogen in domestic dogs and several wild carnivore species. It belongs to the genus Protoparvovirus within the family Parvoviridae [1]. The virus replicates autonomously in host cells, and is genetically related to feline parvovirus (FPV) and mink enteritis virus (MEV), which infect different host animals [2]. The original CPV-2 was first identified in 1978 and has rapidly spread worldwide [[3], [4], [5]]. Soon two antigenic variants, CPV-2a, which emerged in 1979 and contained 5 amino acid substitutions in VP2 [6], and CPV-2b, which appeared in 1984 and had a single additional substitution in VP2 [7], replaced the original type [8]. The third variant CPV-2c with Glu426 mutant emerged in Italy initially [9] and now the three variants have been circulating in dog populations around the world [5,10,11]. CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c are distinguished by one or two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the sequence of the VP2 gene. SNPs at positions 1276 and 1278 of the VP2 gene determine whether residue 426 of the VP2 protein is Asn (CPV-2a), Asp (CPV-2b) or Glu (CPV-2c) [8].

Relative to the original CPV-2, the antigenic variants of CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c are more highly pathogenic in dogs and have an extended host range that includes cats [8]. Infection with any type of the CPVs, dogs show similar signs, which include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration. The CPV types cannot be distinguished by examination or the signs of disease observed from the infected dogs. So we need a method to detect and differentiate the CPV types, which is benefit for treatment of infected dogs with the homogenous polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies of CPV.

Several assays have been reported for the detection or quantitation of CPV DNA [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], including PCR, nested PCR, iiPCR, RPA, LAMP-ELISA, LAMP-LFD, LAMP, polymerase spiral reaction, and SYBR Green based real-time PCR, but none of these assays enable differentiation CPV antigenic types and CPV-like viruses (MEV and FPV). Several other assays have been reported for the detection and differentiation of type 2-based vaccines and field strains of CPV [19] or typing of three antigenic types of CPV [20] or CPV and MEV [21], including PCR-RFLP assay and MGB probe real-time RT-PCR, but none of these assays enables simultaneous detection and differentiation of four antigenic types of CPV.

Molecular diagnostic methods have improved dramatically overthe past years, providing a huge potential for their application inclinical diagnostic where faster and accurate detection of infectious pathogens is required [22]. The real time TaqMan®-based quantitative PCR (qPCR) method, basing on the use of oligonucleotide pairs, relies on improved specificity because only sequence-specific amplifications are measured [23]. In this study, we aimed to develop and evaluate a multiplex TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assay for quantitative and differential detection of CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

The protocol of the study was carried out in accordance with guidelines of animal welfare of World Organization for Animal Health. All experimental protocols were approved by the Review Board Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

2.2. Viruses, cells and samples

The LN15-32 strain of CPV-2, the JL14-1 strain of CPV-2a, the BJ14-1 strain of CPV-2b, the BJ15-20 strain of CPV-2c [24], the CDV3 strain of canine distemper virus (CDV) [25], the CAV-2 strain of canine adenovirus (CAV) [26], and the CCV HB16-2 strain of canine coronavirus (CCV) were also used to test the specificity of primers and probes for related viruses and other dog viruses. F81 [8], Vero [25], and MDCK cells [26] were used to propagate and isolate CPV, CDV, CAV, and CCV, respectively. The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

From the years of 2014–2017, a total of 114 dog fecal samples were collected from different animal hospitals in North China, including Beijing and Hebei. All the samples were tested positive for CPV by PCR and the Anigen Rapid CPV Ag Test Kit (BioNote, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea).

2.3. Primers and probes

The primers and probes were designed based on the alignment of 201 VP2 gene sequences of CPV from GenBank, including 15 strains of CPV-2, 81 strains of CPV-2a, 23 strains of CPV-2b, and 82 strains of CPV-2c (all the sequences see the supplementary file), and synthesized by (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). For discriminating CPV-2 and the variants (CPV-2a, 2b and 2c), CPV-305F/CPV-305R and CPV-2-305P/CPV-2a-305P were designed based on the SNP in the VP2 gene between CPV-2 and the variants (913 G→T). For differentiating CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c, another set of primers and probes, CPV-426F/CPV-426R and CPV-2-426P/CPV-2b-426P/CPV-2c-426P, was designed based on the SNPs in the VP2 gene between the variants (1276 A→G and 1278 T→A). Sequence and position of the primers and probes are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Primers and probes used in the multiplex real-time PCR methods.

| Primers/probes | Sequence(5’→3′) | Positiona | Polarity | Specificity | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPV-2-305P | FAM-ACTCCTATATAACCAAAGTTAGTA-MGB | 900–923 | – | Type 2 | |

| CPV-2a-305P | VIC-ACTCCTATATCACCAAAGTTAG-MGB | 902–923 | – | Types 2a, 2b and 2c | |

| CPV-305F | CGTTGCCTCAATCTGAAGGAGCTA | 878–901 | + | All types | 85 |

| CPV-305R | TTGCCCATTTGAGTTACACCACGT | 939–962 | – | ||

| CPV-2a-426P | FAM-CCTGTAACAAATGATAATGTATTGC-MGB | 1267–1291 | + | Types 2 and 2a | |

| CPV-2b-426P | VIC-CTTCCTGTAACAGATGATAATGTATT-MGB | 1264–1289 | + | Type 2b | |

| CPV-2c-426P | TAMARA-CTTCCTGTAACAGAAGATAATGTATT-MGB | 1264–1289 | + | Type 2c | |

| CPV-426F | AGGAAGATATCCAGAAGGAGATTGGA | 1218–1243 | + | All types | 93 |

| CPV-426R | CCAATTGGATCTGTTGGTAGCAATACA | 1284–1310 | – |

Positions are referred to the nucleotide sequence of strain CPV BJ14-1 (GenBank accession no. KT162022).

2.4. DNA/RNA extraction

DNA samples were extracted from 200 μL of cell culture supernatants or fecal samples using the Takara MiniBEST Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit Ver. 5.0 (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA extraction of CCV and CDV and reverse transcription were performed using procedures described previously [27]. The extracted DNA samples were used as templates in the real-time PCR assays.

2.5. Multiplex real-time PCR standards

The fragments were generated from LN15-32 strain, JL14-1 strain, BJ14-1 strain, and BJ15-20 strain by PCR using primer pair VP2-F/VP2-R [28], and cloned into the pEASY-T1 vector (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and sequenced to generate recombinant plasmids. These recombinant plasmids were used as standards in the multiplex real-time PCR. The plasmids were quantified as described previously [29].

2.6. Optimization of the multiplex real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was conducted in an Applied Biosytems QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR System (ABI, Foster city, USA). The reactions (30 μL) contained 1 μL of template or standard DNA plasmids, 15 μL of Taqman Multiplex Master mix (ABI, Warrington, UK), 200 nM of primers CPV-305F/CPV-305R (CPV-2 and the variants assay) or CPV-426F/CPV-426R (CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay), 200 nM of probes CPV-2-305P/CPV-2a-305P (CPV-2 and the variants assay), or 200 nM of probes CPV-2-426P/CPV-2b-426P and 300 nM of probe CPV-2c-426P (CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay). Two different wells were used for each test sample and each dilution of standard DNA plasmids. After activation of Taq DNA polymerase at 94 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of two-step PCR were performed, consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 5 s and primer annealing-extension at 61 °C (CPV-2 and the variants assay) or 63 °C (CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay) for 34 s. The increase in fluorescent signal was registered during the annealing-extension step of the reaction and the data were analyzed with QuantStudioTM Design & Analysis Software (Applied Biosytems, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.7. Specificity of the multiplex real-time PCR

The multiplex real-time RT-PCR was evaluated for its specificity by testing LN15-32 strain (CPV-2), JL14-1 strain (CPV-2a), BJ14-1 strain (CPV-2b), and BJ15-20 strain (CPV-2c), and three other unrelated canine viruses including CDV, CAV, and CCV. RNA or DNA samples, which were extracted from infected or mock-infected cell cultures, and cDNA samples synthesized from the RNA and DNA were subjected to assays using the multiplex real-time PCR.

2.8. Sensitivity of the multiplex real-time PCR

Serial 10-fold dilutions of each standard DNA plasmids (type 2, 2a, 2b and 2c), ranging from 108 to 100 DNA copies/μL of the template, were subjected to detection by the multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR for assay limit.

2.9. Reproducibility of the multiplex real-time PCR

Inter-assay and intra-assay reproducibility tests were performed in triplicate by testing three different titers of cell cultures infected with LN15-32, JL14-1, BJ14-1, and BJ15-20 strains, respectively, to evaluate the reproducibility of the multiplex real-time PCR assay.

2.10. Comparative test

A total of 114 dog fecal samples, which were tested positive for CPV using a PCR method as described previously [8] and the Anigen Rapid CPV Ag Test Kit (BioNote, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea), were tested in parallel using the multiplex real-time PCR method and a DNA sequencing method as described previously [8].

3. Results

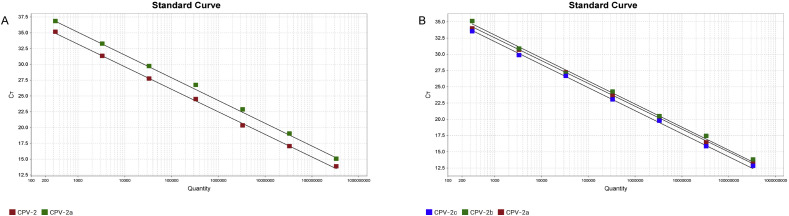

3.1. Establishment of standard curve of the multiplex real-time PCR

The generated standard curve based on serial 10-fold dilutions of CPV plasmid DNAs. In the CPV-2 and its variants assay, the real-time PCR gave linear curves for 108∼102 copies/μL of CPV-2 and CPV-2a standards, with correlation coefficient (R2) = 0.999, amplification efficiency (E) = 91% for CPV-2; R2 = 0.998, E = 87% for CPV-2a (Fig. 1 A). In the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay, the real-time PCR gave linear curves for 108∼102 copies/μL of CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c standards, with R2 = 0.999, E = 93% for CPV-2a; R2 = 0.996, E = 92% for CPV-2b and R2 = 0.996, E = 92% for CPV-2c (Fig. 1B). Samples with CT value ≤ 38 were considered as positive; samples without CT (NCT) were considered as negative; samples with an amplification curve (above threshold line) but with a CT value between 38 and 40 were considered doubtful, and were to be repeated to test or subjected to virus isolation for confirmative detection.

Fig. 1.

Standard curves of multiplex real-time PCR.

The x-axis represents copies of plasmid DNA in 10-fold dilutions, and the y-axis represents the fluorescence data used for cycle threshold (Ct) determinations. A: the CPV-2 and its variants assay. The assays were linear in the range of 102 to 108 template copies/μL, with correlation coefficient (R2) = 0.999, amplification efficiency (E) = 91% for CPV-2; R2 = 0.998, E = 87% for CPV-2a; B: the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay. The assays were linear in the range of 102 to 108 template copies/μL, with R2 = 0.999, E = 93% for CPV-2a; R2 = 0.996, E = 92% for CPV-2b and R2 = 0.996, E = 92% for CPV-2c.

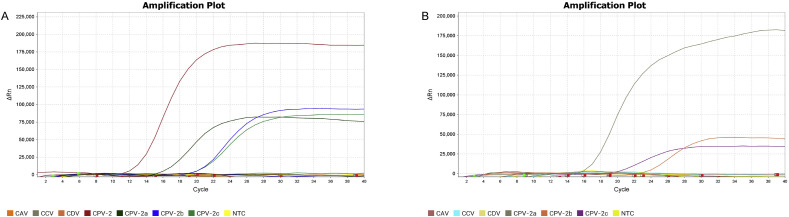

3.2. Specificity of the multiplex real-time PCR

The multiplex real-time PCR was able to differentiate each among four antigenic types CPV in samples of single virus or virus mixtures in the respective detection channels (FAM for CPV-2, VIC for CPV-2a in CPV-2 and the variants assay; FAM for CPV-2a, VIC for CPV-2b, and TAMARA for CPV-2c in CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay), without appearing specific signals in non-target channels over 40 cycles (including the DNA or cDNA preparations from CDV, CAV, CCV, and water controls). NCT was performed in any channel for cell cultures of several irrelevant viruses (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Specificity of multiplex real-time PCR. A: the CPV-2 and its variants assay. FAM fluorescent signals were generated only by CPV-2 DNA and VIC fluorescent signals were generated by DNA of CPV-2a, or 2b or 2c; B: the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay. FAM fluorescent signals were generated by CPV-2a DNA, VIC fluorescent signals were only generated by CPV-2b DNA and TAMARA fluorescent signals were only generated by CPV-2c DNA. No fluorescent signal was not obtained from CDV, CAV, CCV, and sterile water in the multiplex real-time PCR.

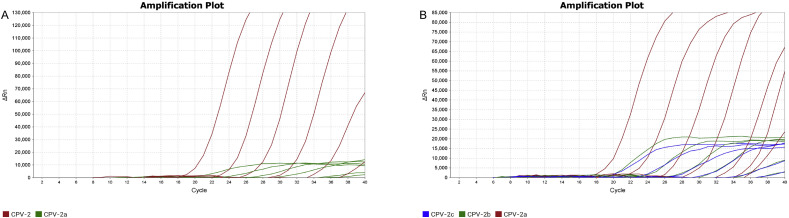

3.3. Detection limit of the multiplex real-time PCR

With serial dilutions of CPVs, the multiplex real-time PCR detected at least 101∼102 DNA copies per reaction. The detection limits for the CPV-2 and its variants were 101 and 102 genome copies for CPV-2 and CPV-2a, respectively (Fig. 3 A), and that of CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay were 101, 101 and 102 genome copies, respectively (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Detection limit of the multiplex real-time PCR. A: The detection limits are 101 and 102 DNA copies for types 2 and 2a, respectively, in the CPV-2 and its variants assay; B: The detection limits are 101, 101 and 102 DNA copies for types 2a, 2b and 2c, respectively, in the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay.

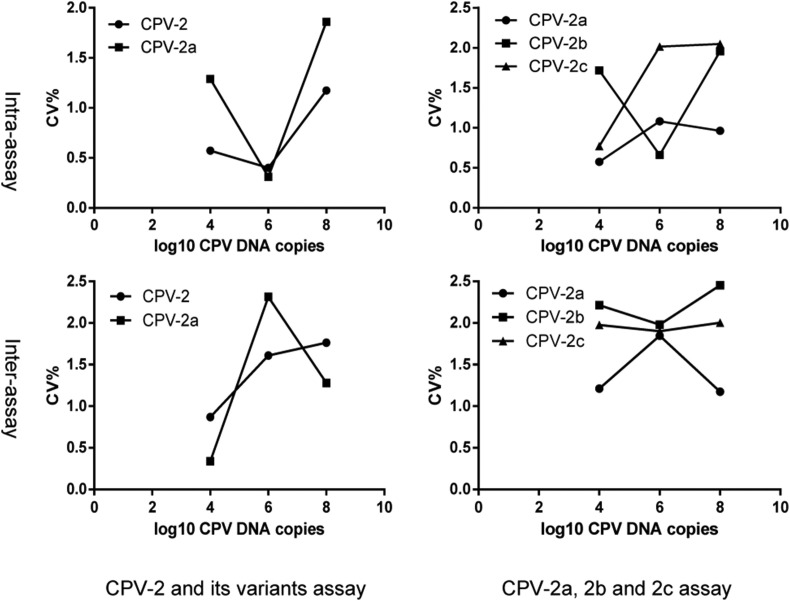

3.4. Reproducibility of the multiplex real-time PCR

The intra-assay and inter-assay reproducibility test indicated that the multiplex real-time PCR was reproducible. Both the coefficients of variation of the CPV-2 and its variants assay and the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay were between 0.2% and 2.5% in intra-assay and inter-assay, with three independent tests of CPV-2 and CPV-2a and CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c at three various genome copies (104, 106, and 108), as determined in triplicate (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variations (CV%) of the multiplex real-time PCR. Low (104), medium (106) and high concentration (108) genome copies were conducted in the CPV-2 and its variants assay and the CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay in triplicate. CVs of intra-assay and inter-assay were less than 2.5%.

3.5. Typing of CPV by multiplex real-time PCR and DNA sequencing

A total of 114 dog clinical samples were tested by the multiplex real-time PCR assay, and the results obtained were compared with the antigenic types derived by conventional sequencing methods [8]. All the 114 samples were CPV positive as tested both by conventional PCR and immunochromatographic strip assays. In the CPV-2 and its variants assay, 2 samples gave FAM fluorescent signals and the others (112) gave VIC fluorescent signals; and in CPV-2a, 2b and 2c assay, 57, 25, and 30 out of the 112 samples gave FAM, VIC, and TAMARA fluorescent signals, respectively. Thus, the results of the multiplex real-time PCR showed that 2 (1.8%), 57 (50.0%), 25 (21.9%), and 30 (26.3%) samples were characterized as CPV types 2, 2a, 2b, and 2c in China, respectively. Meanwhile the DNA of 114 dog fecal samples were sequenced by traditional Sanger sequencing methods, and the analysis of the VP2 gene sequence indicated that the DNA sequencing results were in a perfect agreement with that of multiplex real-time PCR. Virus isolation was also performed from some samples and we detected four antigenic types of CPV isolates. Forty-nine samples were subjected to virus isolation, and 2 CPV-2, 15 CPV-2a, 8 CPV-2b, and 9 CPV-2c isolates were obtained.

4. Discussion

CPV causes acute hemorrhagic enteritis and myocarditis in dogs [5], and the mortality rate of the disease is high (up to 70%) in puppies [11,14]. The main method for controlling the disease in domestic animals is by vaccination. However, the evolution of CPV raises questions about the efficacy of the vaccines [5,30,31]. Thus, the development of a simple and rapid diagnostic tool that could detect and differentiate four types of CPV in the clinical samples is in valuable for epidemiological surveillance and prediction of the severity of CPV infection in dogs.

To identify CPV infection, several methods have been developed based on the specific antigens or the genome of the virus. Initially, CPV typing was performed by agar gel precipitin (AGP) test using monoclonal antibodies (MAb) or by the virus neutralization test or the hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay [[32], [33], [34]]. CPV was readily distinguished from the FPV and MEV isolates using AGP test with 6 MAbs generated against CPV [34]. CPV-2b could be distinguished from the CPV-2 and CPV-2a by the reactivity of two MAbs, MAb I and MAb B [7]; and CPV-2b could be distinguished from CPV-2a with MAb 21C3 [32]. However, all these MAbs are not able to recognize CPV-2c. With three MAbs, B4A2, 21C3 and 19D7, one CPV-2c isolate (HNI-4-1) was distinguished from CPV-2b by HI assay [33]. The HI test using MAbs need fresh erythrocyte and could not be used for non-haemagglutinating strains [35].

The PCR and restriction enzyme analysis with MboⅡcan differentiate CPV-2c from other types, but it cannot differentiate CPV-2, CPV-2a and CPV-2b [9,36,37]. Gupta et al. developed an isothermal amplification technique, polymerase spiral reaction (PSR), for detection of CPV genomic DNA. PSR was a simple, rapid, and cost effective method for diagnosis of canine parvoviral enteritis in veterinary clinics, but it cannot differentiate CPV-2 from its variants [18]. Mini-sequencing based single nucleotide polymorphism analysis was developed for CPV typing [38], but it was time-consuming and expensive. Compared to conventional PCR, real-time PCR is more sensitive and time saving for detection of viral DNA. A SYBR Green based real-time PCR assay was developed for detection and quantitation of CPV in fecal samples of dogs [13]. A TaqMan real-time PCR assay was developed to discriminate between type 2-based vaccines and field strains of CPV [19], and another assay was used to identify the variants [39].

In this study, we developed and fully validated a multiplex real-time PCR assay based on TaqMan technology for simultaneous detection and differentiation of CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c. The assay is specific and sensitive, as no amplification was detected by other viruses, CDV, CAV, and CCV, and the detection limit is as low as 101 genome copies. When combined samples of CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c of different titers were tested by the multiplex real-time PCR assay, four targets can be detected simultaneously and consistently without interference each other.

In the TaqMan real-time PCR assay developed by Decaro et al., the primers and probes were designed by taking into consideration of the SNPs ATT301-3ACT of VP2 gene between CPV-2 and its variants, which may give false-negative results for CPV isolates in China [19]. Because there is a T302C mutation of VP2 gene in type 2 isolate HB3 (GenBank No. GU392238), and a T303C mutation of VP2 gene in the circulating variants, for example, isolate BJ15-6 (type 2a, GenBank No. KT162043), isolate BJ15-12 (type 2b, GenBank No. KT162027) and isolate 06/09 (type 2c, GenBank No. GU380303), in China. In the study, we designed the primers and probes of CPV-2 and the variants assay based on the SNP G913T between CPV-2 and the variants, and the nucleotide at position 913 was conserved in circulating strains in China. Therefore, we conclude that the multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR assay we reported here is suitable for detection and differentiation of all CPV variants in China.

Of the 114 field samples in this study, 112 were positive for the CPV variants when assayed by the multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR, indicating the CPV-2a/2b/2c were the predominant antigenic variants in China. Interestingly, we found 2 samples were the original CPV type 2 tested by the assay. To confirm the results, the 2 CVP-2 strains were verified by DNA sequencing and virus isolation. The original CPV type 2 was replaced by the genetic and antigenic variants worldwide, including China [8,10,11,40]. We currently do not know why the CPV-2 has reemerged in dogs in China. Apparently, more work needs to be done to answer this question.

In this study we developed a multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR assay for simultaneous detection and differentiation of current CPV variants in clinical samples from dogs.

Authors' contributions

JK Wang wrote the manuscript, YR Sun and YN Cheng carried out the experiments with the help of MW Tong who carried out primers design, L Yi and WZ Yuan contributed to the clinical samples collection, SP Cheng and GL Wang carried out sequence analysis, S Li carried out PCR. P Lin, ZG Cao and MW Tong revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank professor Jianming Qiu (Department of Microbiology, Molecular Genetics and Immunology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA) for revising the manuscript. The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31602056), Jilin Provincial Key Science and Technology Project Fund (No. 20150204021 NY), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (No. 1610342016028) and Jilin Provincial Major Science and Technology Development Project Fund (No. 20150201006 NY).

References

- 1.Cotmore S.F., Agbandje-McKenna M., Chiorini J.A., Mukha D.V., Pintel D.J., Qiu J., Soderlund-Venermo M., Tattersall P., Tijssen P., Gatherer D., Davison A.J. The family Parvoviridae. Arch. Virol. 2014;159(5):1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaur G., Chandra M., Dwivedi P.N., Sharma N.S. Antigenic typing of canine parvovirus using differential PCR. Virusdisease. 2014;25(4):481–487. doi: 10.1007/s13337-014-0232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel M.J., Scott F.W., Carmichael L.E. Isolation and immunisation studies of a canine parco-like virus from dogs with haemorrhagic enteritis. Vet. Rec. 1979;105(8):156–159. doi: 10.1136/vr.105.8.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson R.H., Spradbrow P.B. Isolation from dogs with severe enteritis of a parvovirus related to feline panleukopenia virus. Aust. Vet. J. 1979;55(3):151–152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miranda C., Thompson G. Canine parvovirus: the worldwide occurrence of antigenic variants. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97(9):2043–2057. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrish C.R., O'Connell P.H., Evermann J.F., Carmichael L.E. Natural variation of canine parvovirus. Science. 1985;230(4729):1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.4059921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrish C.R., Aquadro C.F., Strassheim M.L., Evermann J.F., Sgro J.Y., Mohammed H.O. Rapid antigenic-type replacement and DNA sequence evolution of canine parvovirus. J. Virol. 1991;65(12):6544–6552. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6544-6552.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J., Lin P., Zhao H., Cheng Y., Jiang Z., Zhu H., Wu H., Cheng S. Continuing evolution of canine parvovirus in China: isolation of novel variants with an Ala5Gly mutation in the VP2 protein. Infect Genet E. 2016;38:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buonavoglia C., Martella V., Pratelli A., Tempesta M., Cavalli A., Buonavoglia D., Bozzo G., Elia G., Decaro N., Carmichael L. Evidence for evolution of canine parvovirus type 2 in Italy. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82(Pt 12):3021–3025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao H., Wang J., Jiang Y., Cheng Y., Lin P., Zhu H., Han G., Yi L., Zhang S., Guo L., Cheng S. Typing of canine parvovirus strains circulating in North-East China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(2):495–503. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decaro N., Buonavoglia C. Canine parvovirus–a review of epidemiological and diagnostic aspects, with emphasis on type 2c. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;155(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhopadhyay H.K., Amsaveni S., Matta S.L., Antony P.X., Thanislass J., Pillai R.M. Development and evaluation of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of canine parvovirus DNA directly in faecal specimens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;55(3):202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar M., Nandi S. Development of a SYBR Green based real-time PCR assay for detection and quantitation of canine parvovirus in faecal samples. J. Virol Meth. 2010;169(1):198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkes R.P., Lee P.Y., Tsai Y.L., Tsai C.F., Chang H.H., Chang H.F., Wang H.T. An insulated isothermal PCR method on a field-deployable device for rapid and sensitive detection of canine parvovirus type 2 at points of need. J. Virol Meth. 2015;220:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J., Liu L., Li R., Wang J., Fu Q., Yuan W. Rapid and sensitive detection of canine parvovirus type 2 by recombinase polymerase amplification. Arch. Virol. 2016;161(4):1015–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2738-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uwatoko K., Sunairi M., Nakajima M., Yamaura K. Rapid method utilizing the polymerase chain reaction for detection of canine parvovirus in feces of diarrheic dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 1995;43(4):315–323. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y.L., Yen C.H., Tu C.F. Visual detection of canine parvovirus based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and with lateral flow dipstick. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014;76(4):509–516. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta V., Chakravarti S., Chander V., Majumder S., Bhat S.A., Gupta V.K., Nandi S. Polymerase spiral reaction (PSR): a novel, visual isothermal amplification method for detection of canine parvovirus 2 genomic DNA. Arch. Virol. 2017;162(7):1995–2001. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decaro N., Elia G., Desario C., Roperto S., Martella V., Campolo M., Lorusso A., Cavalli A., Buonavoglia C. A minor groove binder probe real-time PCR assay for discrimination between type 2-based vaccines and field strains of canine parvovirus. J. Virol Meth. 2006;136(1-2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur G., Chandra M., Dwivedi P.N., Narang D. Multiplex real-time PCR for identification of canine parvovirus antigenic types. J. Virol Meth. 2016;233:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C., Yu Y., Yang H., Li G., Yu Z., Zhang H., Shan H. Development of a PCR-RFLP assay for the detection and differentiation of canine parvovirus and mink enteritis virus. J. Virol Meth. 2014;210:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowgier G., Mari V., Losurdo M., Larocca V., Colaianni M.L., Cirone F., Lucente M.S., Martella V., Buonavoglia C., Decaro N. A duplex real-time PCR assay based on TaqMan technology for simultaneous detection and differentiation of canine adenovirus types 1 and 2. J. Virol Meth. 2016;234:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ligozzi M., Diani E., Lissandrini F., Mainardi R., Gibellini D. Assessment of NS1 gene-specific real time quantitative TaqMan PCR for the detection of Human Bocavirus in respiratory samples. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2017;34(Supplement C):53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J.K. Chin. Acad. Agric. Sci.; Beijing: 2016. Molecular Characterization and Pathogenicity of Carnivore Parvovirus Epidemic Isolates; pp. 41–78. (Ph.D. thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi L., Cheng S., Xu H., Wang J., Cheng Y., Yang S., Luo B. Development of a combined canine distemper virus specific RT-PCR protocol for the differentiation of infected and vaccinated animals (DIVA) and genetic characterization of the hemagglutinin gene of seven Chinese strains demonstrated in dogs. J. Virol Meth. 2012;179(1):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Y., Zhang M. Establishment of process to produce live vaccine of fox encephalitis (CAV-2c strain) Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2016;10:253–254. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng Y., Wang J., Zhang M., Zhao J., Shao X., Ma Z., Zhao H., Lin P., Wu H. Isolation and sequence analysis of a canine distemper virus from a raccoon dog in Jilin Province, China. Virus Gene. 2015;51(2):298–301. doi: 10.1007/s11262-015-1236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin P., Wang H.M., Wang J.K., Zhao H., Guo L., Yang Y., Cheng Y.N., Zhang M., Cheng S.P. Prokaryotic expression and identification of mink enteritis virus VP2 gene. J. Econ. Anim. 2015;19(03):133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X.J., Han Q.Y., Sun Y., Zhang X., Qiu H.J. Development of a triplex TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assay for differential detection of wild-type and HCLV vaccine strains of classical swine fever virus and bovine viral diarrhea virus 1. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012;92(3):512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez-Blanco B., Catala-Lopez F. Are licensed canine parvovirus (CPV2 and CPV2b) vaccines able to elicit protection against CPV2c subtype in puppies?: A systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;180(1–2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolford L., Crocker P., Bobrowski H., Baker T., Hemmatzadeh F. Detection of the canine parvovirus 2c subtype in australian dogs. Viral Immunol. 2017;30(5):371–376. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura M., Nakamura K., Miyazawa T., Tohya Y., Mochizuki M., Akashi H. Monoclonal antibodies that distinguish antigenic variants of canine parvovirus. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2003;10(6):1085–1089. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.6.1085-1089.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura M., Tohya Y., Miyazawa T., Mochizuki M., Phung H.T., Nguyen N.H., Huynh L.M., Nguyen L.T., Nguyen P.N., Nguyen P.V., Nguyen N.P., Akashi H. A novel antigenic variant of Canine parvovirus from a Vietnamese dog. Arch. Virol. 2004;149(11):2261–2269. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0367-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parrish C.R., Carmichael L.E., Antczak D.F. Antigenic relationships between canine parvovirus type 2, feline panleukopenia virus and mink enteritis virus using conventional antisera and monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 1982;72(4):267–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01315223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavalli A., Bozzo G., Decaro N., Tinelli A., Aliberti A., Buonavoglia D. Characterization of a canine parvovirus strain isolated from an adult dog. New Microbiol. 2001;24(3):239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Touihri L., Bouzid I., Daoud R., Desario C., El Goulli A.F., Decaro N., Ghorbel A., Buonavoglia C., Bahloul C. Molecular characterization of canine parvovirus-2 variants circulating in Tunisia. Virus Gene. 2009;38(2):249–258. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar M., Nandi S. Molecular typing of canine parvovirus variants by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. Transboundary Emerg. Dis. 2010;57(6):458–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naidu H., Subramanian B.M., Chinchkar S.R., Sriraman R., Rana S.K., Srinivasan V.A. Typing of canine parvovirus isolates using mini-sequencing based single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. J. Virol Meth. 2012;181(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decaro N., Elia G., Martella V., Campolo M., Desario C., Camero M., Cirone F., Lorusso E., Lucente M.S., Narcisi D., Scalia P., Buonavoglia C. Characterisation of the canine parvovirus type 2 variants using minor groove binder probe technology. J. Virol Meth. 2006;133(1):92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang R., Yang S., Zhang W., Zhang T., Xie Z., Feng H., Wang S., Xia X. Phylogenetic analysis of the VP2 gene of canine parvoviruses circulating in China. Virus Gene. 2010;40(3):397–402. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]