Abstract

Introduction

Acute Lung Injury (ALI) with genetic predisposition is fatal. Relationship between angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion (ACE I/D) polymorphism and the prognosis of local Chinese patients with ALI was investigated; meanwhile, the mechanisms involved were explored.

Methods

101 ALI patients, 408 non-ALI patients and 236 healthy blood donors were enrolled. ACE I/D polymorphism was detected by polymerase chain reaction, then ACE genotype (II, ID, DD) and allele (I, D) frequencies were compared. Clinical data of ALI patients was calculated. Also, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from healthy volunteers with different ACE genotypes. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced ACE gene mRNA expression and ACE activity was measured.

Results

There was no significant difference in the frequencies of the genotypes and alleles. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was higher in DD subgroup than in II subgroup (19.7 ± 8.7 and 15.6 ± 6.2; P < 0.05). The 28-day mortality was significantly different (17.4%, 26.8%, and 64.3% for II, ID, and DD; P = 0.013). DD genotype was the independent prognostic factor for 28-day outcome. Furthermore, LPS-induced ACE mRNA expression and ACE activity from PBMC in DD genotype subgroup were both significantly higher than those in the other two subgroups.

Conclusions

ACE I/D polymorphism is a prognostic factor for ALI. Patients with the DD genotype have higher mortality of ALI. Polymorphism influences the expression of ACE gene in LPS-stimulated PBMC, DD genotype leads to higher level of mRNA and enzyme activity. It may be one of the mechanisms involved.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, Polymorphism, Acute lung injury, Outcome

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) with high mortality remains a common disease in intensive care unit (ICU). Generally speaking, infection is the primary cause, which induces excessive cytokines from inflammatory cells and enhances inflammatory response. Factors predicting the onset, severity or outcome of this disease are not well known. Experimental evidence suggests that activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), especial angiotensin (AT) may influence the pathogenesis of ALI via affecting inflammation including producing inflammatory factors and apoptosis.1 Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is a key enzyme that converts AT-I to AT-II. The human ACE gene is located on chromosome 17q23, while its polymorphism is consists of the presence (insertion, I) and absence (deletion, D) of a 287-bp Alu repeat sequence in intron 16.2 ACE I/D polymorphism has been shown to influence the prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome,2 and is different with various races and districts.3 There was no report of ACE genotypes in the Han Chinese with ALI in the district.

We therefore focused on the relationship between ACE I/D polymorphism and the onset and prognosis of ALI. And we also investigated the effects of ACE I/D genotypes on ACE level from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

Methods

Study population

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Southeast University (Nanjing, China). Over a period of one year, patients over 18-year-old, which divided into two groups, ALI and non-ALI patients, admitted to a specialized ICU of Zhongda Hospital, were considered eligible for the study. Healthy blood donors were healthy subjects’ donors during the same period. All subjects were ethnical Chinese and were not genetically related.

ALI patients fulfilled the joint American/European Consensus Committee criteria for ALI: a) acute onset, b) bilateral pulmonary infiltrations, c) impaired oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2 of <300 mmHg), and d) pulmonary artery occlusion pressure of <18mmHg, or no evidence of left heart failure. Patients in the non-ALI group were all admitted to the hospital over the same period due to other diseases. Healthy controls were healthy blood donors. They were all local Chinese with no gender differences. Exclusion criteria were: a) history of ALI, b) received ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor antagonist within one month before the development of ALI, c) having liver or renal failure in terminal stage, d) pregnancy or lactation, e) malignant tumor or immunological disease, f) history of bone marrow transplant or lung transplant, g) received immunosuppressive drug, h) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) < 7.

Clinical data collection and outcome

The following data were collected from the ALI group: sex, age, reason for admission, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) sores, Lung Injury Scores (LIS), PaO2/FiO2, duration of mechanical ventilation and vasoactive agents, number of organ failure, duration of ICU stay and 28-day mortality.

Determination of ACE genotypes

DNA was extracted from whole blood samples by modified phenol-chloroform extraction. ACE genotype was determined by three-primer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification as described previously.4 This method yielded amplification products of 83 bp for D allele and 65 bp for I allele. Standard polymerase chain primer was performed with three primers (5′-CATCCTTTCTCCCATTTCTC-3′, 5′-ATTTCAGAGCTGGAATAAAATT-3′ and 5′-TGGGATTACAGGCGTGATACAG-3′). The DNA was amplified for 35-cycled with denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealling at 53 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were identified on polyacrylamide gels. The genotypic distributions and allelic frequencies of ACE I/D polymorphism among the three groups were calculated.

Preparation of PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from whole blood of healthy blood donors by density gradient centrifugation (LTS 1077, Hao Yang Biological Manufacture Co. Ltd, Tianjin, China). The buffy coat layer containing PBMC at the interface was carefully removed, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies), and incubated in the presence of 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C in 24-well plates. After 6 h or 24 h incubation period with or without LPS incubation (final concentration of LPS 0.1 μg/ml), cells or supernatant were collected.

Isolation of mRNA and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured PBMC cells using TRNZOL (DP405-01, Tiangen Biological Manufacture Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the instruction from the manufacture. After RNA was transcribed with TaKaRa PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit (DRR014A, TAKARA Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Dalian, China), PCR amplification of cDNA was done. Primer pairs of ACE were 5′- CAGGAGTGGAGACCGAGA-3′(sense) and 5′-CCAGACAAGCCCAACCTC -3′(anti-sense) with a predicted size 394 bp. The cycle profile included denaturation for 30 s at 94 °C, annealing for 60 s at 59 °C and extension for 40 s at 72 °C. Human β-actin, regarded as internal control for stable expression, was amplified with primers of 5′- CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG-3′(sense) and 5′- TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′(anti-sense) with a predicted size 207 bp. The cycle profile included denaturation for 30 s at 94 °C, annealing for 60 s at 53 °C and extention for 40 s at 72 °C. The resulting densities of the ACE bands were expressed relative to the corresponding density of the actin band from the same RNA sample.

Measurement of ACE activity

The ACE activity of cultural cells supernatant was measured by hydrolysis of hippuril-glycyl-glycine. Briefly, hippuroyl glycyl-glycine was hydrolysis into hippuric acid and glycyl-glycine by ACE. And hippuric acid was extracted by ethyl acetate and distilled, then soluted in sodium chloride. The mixture was monitored ultraviolet spectrophotometrically at 228 nm.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistical package (version 13.0) was used for the statistical analysis. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons of the continuous data were performed by homogeneity test for variance firstly. Then the data were analyzed by ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis, Mann–Whitney test. The chi-square tables were used to compare the distribution of genotypes and alleles frequencies. The 28-day survival rate among the genotype groups was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Multivariate logistic-regression analysis was used to assess prognostic factors. For all test, a p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical data of ALI and non-ALI patients, and control subjects

101 ALI patients (age, 65.1 ± 16.5 yrs; 68 men and 33 women), 408 non-ALI patients and 236 healthy subjects were enrolled. Clinical characteristics of ALI patients were summarized in Table 1 . The common causes of ALI patients in this study were pneumonia (61.4%), sepsis (18.8%) and trauma (12.9%).

Table 1.

Clinical data of ALI patients (n = 101, ).

| Variables | (n = 101) |

|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 65.1 ± 16.5 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 68 (67.3%) |

| Causes of ALI, n (%) | |

| Lung trauma | 13 (12.9%) |

| Pneumonia | 62 (61.4%) |

| Sepsis | 19 (18.8%) |

| Others | 7 (6.9%) |

| APACHEⅡ score | 16.6 ± 6.9 |

| SOFA score | 7.9 ± 3.8 |

| Lung injury score | 1.33 ± 0.66 |

| PaO2/FiO2 (mm Hg) | 201.9 ± 56.6 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) | 5.4 ± 6.4 |

| Duration of vasoactive agents (days) | 2.5 ± 3.1 |

| Number of organ failures | 2.5 ± 1.2 |

| Duration of ICU Stay (days) | 10.7 ± 8.9 |

APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; SOFA: Sequential organ failure assessment; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen.

Genotypes and allele frequencies of ACE polymorphism data

Table 2 summarized the ACE genotype (II, ID, and DD) and allele (I and D) frequencies of the three groups. DD genotype accounted for a similar percentage (13.8%, 10.1% and 9.8%, respectively; p > 0.05). The frequencies of D allele in three groups were 34.2%, 35.7% and 32%, respectively. Comparisons showed that there was no significant difference in the genotype and allele frequencies among these groups.

Table 2.

Genotype and allele frequencies of ACE polymorphism.

| ALI (n = 101) | Non-ALI (n = 408) | Normal control (n = 236) | p value (ALI vs Non-ALI) | p value (ALI vs normal control) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | 0.143 | 0.512 | |||

| II | 46(45.6%) | 158(38.7%) | 108(45.7%) | ||

| ID | 41(40.6%) | 209(51.2%) | 105(44.5%) | ||

| DD | 14(13.8%) | 41(10.1%) | 23(9.8%) | ||

| Allele | 0.377 | 0.322 | |||

| I | 65.8% | 64.3% | 68% | ||

| D | 34.2% | 35.7% | 32% | ||

Effect of ACE I/D polymorphism on the severity of ALI

APACHE II score of DD genotype was 19.7 ± 8.7, which was significantly higher in the patients with II or ID genotype (15.6 ± 6.2 or 16.6 ± 6.8). However, SOFA sore, LIS, PaO2/FiO2, duration of mechanical ventilation and vasoactive agents, number of organ failure, duration of ICU stay were all similar among the three genotypes (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Effect of ACE genotype polymorphism on the severity of ALI.

| Genotype | APACHEⅡ | SOFA | Number of organ failure | Lung injury score | During of mechanical ventilation (days) | Duration of ICU stay (days) | Duration of vasoactive agent (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | 15.6 ± 6.2 | 7.5 ± 3.8 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.67 | 5.1 ± 6.3 | 9.9 ± 8.3 | 2.3 ± 3.2 |

| ID | 16.6 ± 6.8 | 7.9 ± 3.4 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 0.65 | 5.3 ± 6.9 | 11.4 ± 9.5 | 2.4 ± 3.1 |

| DD | 19.7 ± 8.7a | 9.4 ± 4.3 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.70 | 6.4 ± 5.2 | 11.3 ± 9.6 | 3.8 ± 2.8 |

Severity of illness scores was calculated on Day 1 of ALI. Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

p = 0.048 compared with the ALI group.

Effect of ACE I/D polymorphism on the outcome of ALI

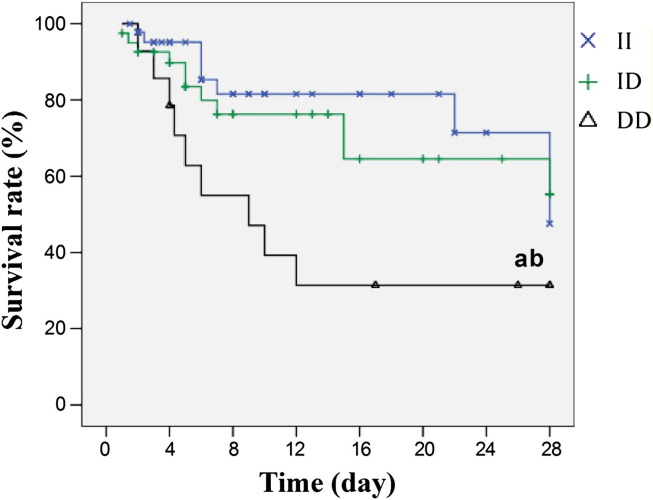

The 28-day mortality of the ALI patients was 27.7%. The 28-day mortality was significantly different among the three ACE genotypes (17.4%, 26.8%, and 64.3% for II, ID, and DD, respectively; p = 0.013). Patients with the DD genotype had a lower possibility of survival for 28 days as compared with other groups (Fig. 1 ). Table 4 showed the results of survival analysis and demonstrated that DD genotype (Odd ratio, 8.80; 95% confidence interval, 1.75–44.06; p = 0.008) was the significant independent prognostic factors for the 28-day outcome.

Figure 1.

Effect of ACE I/D genotype polymorphism on the 28-day survival rate of ALI (Kaplan–Meier method). aP<0.05 vs II subgroup and bP<0.05 vs ID subgroup.

Table 4.

Analyses of factors associated with 28-day mortality in patients with ALI.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ACE DD genotype | 8.80 (1.75–44.07) | 0.008 |

| APACHE II score | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | 0.622 |

| Number of organ failure | 1.15 (0.49–2.73) | 0.745 |

| SOFA | 1.34 (0.98–1.84) | 0.067 |

| Lung injury score | 2.60 (0.97–7.02) | 0.059 |

| During of mechanical ventilation | 1.05 (0.96–1.14) | 0.293 |

OR, odd ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II.

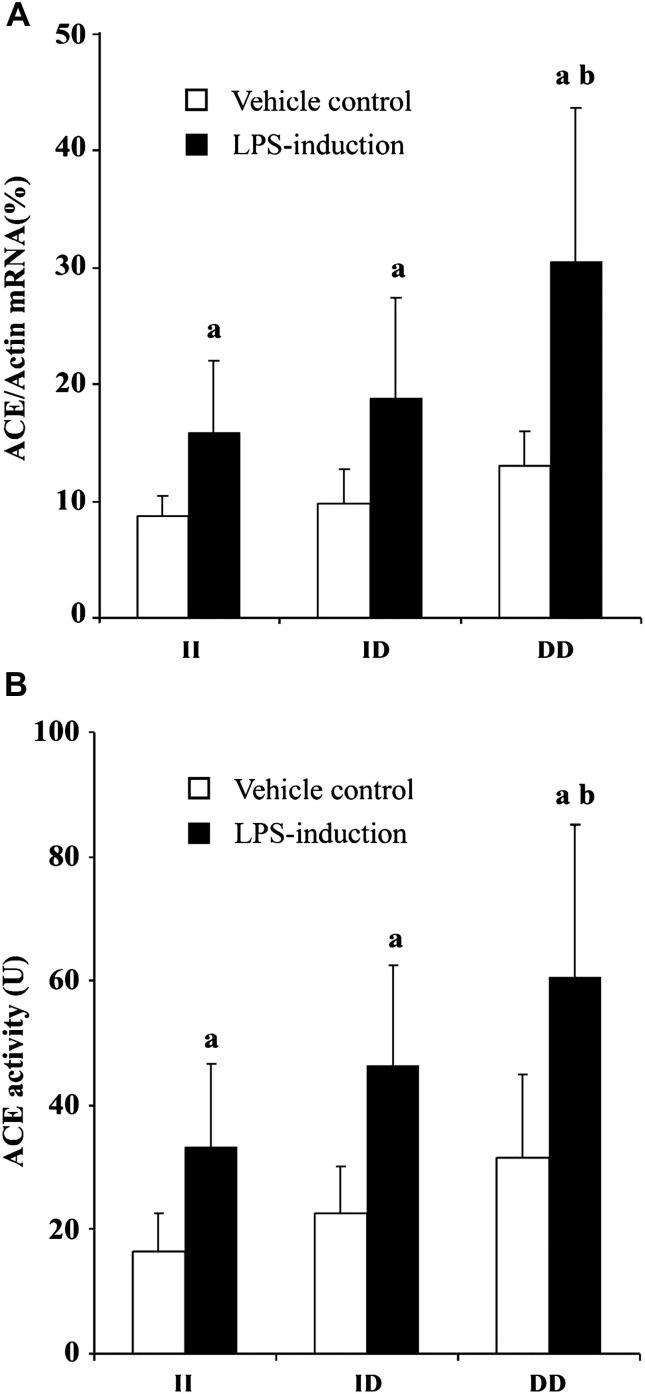

Expression of ACE mRNA of LPS-induced PBMC

After incubation for 6 h, ACE mRNA expressions of LPS-induced PBMC with different genotypes were markedly increased. Among the three genotypes, PBMC of DD genotype had the highest ACE mRNA expression after exposure to LPS (30.55 ± 13.14%, 15.92 ± 6.11% and 18.76 ± 8.69% for DD genotype, II genotype and ID genotype group, respectively, P = 0.038) (Fig. 2 A).

Figure 2.

Effect of ACE I/D genotype polymorphism on ACE mRNA expression (A) and ACE activity (B) of LPS-induced PBMC. PBMC was exposed to LPS (0.1 μg/ml) for 6 h, and then total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed. Also, the cellular supernatant was collected for the following ACE activity determination. Data are the mean ± s.d. of three experiments. aP<0.05 vs vehicle control, bP<0.05 vs II group.

ACE activity of LPS-induced PBMC

As shown in Fig. 2B, after incubation of LPS for 24 h, ACE activity in cell cultured supernatant was higher than that in control group (P < 0.05). The ACE activity of the PBMC with DD genotype was significantly higher compared with that with II genotype group, (60.76 ± 24.55 U and 33.33 ± 13.32 U, respectively, P = 0.01). And The ACE activity of the PBMC with ID genotype (46.31 ± 16.30 U) had no significantly difference with other two genotype groups.

Discussion

It has been shown that there are marked ethnic differences in the polymorphisms of the ACE gene.3 Reports from the western countries indicated that the D allele frequency was usually higher than that of I allele, accounting for 51%–56% in the general population,5 whereas in the Asian countries, the frequency of the D allele was lower.3 In our study, the D allele frequency of local Chinese was 32%–35.7%. As shown in the reports from Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, the D allele frequency among ethnic Chinese people was 30%–45%. This may result in a smaller proportion of people carrying the DD genotype, ranging from 9.8% to 13.8% in our study, and it was similar to those previously reported in Chinese ethnic populations, ranging from 9% to 16%.

Our study showed that the ALI patients with the DD genotype of the ACE gene had higher 28-day mortality. Meanwhile, there was a similar distribution of genotypes and allele frequencies of the ACE I/D gene in patients with ALI, non-ALI and healthy control subjects. This study therefore suggested that the polymorphism was associated with the outcome rather than risk for ALI in the local Chinese population.

ACE I/D polymorphism was not associated with the susceptibility of ALI in our finding. Just like many similar studies suggested that the genotype was not an independent risk factor.6, 7 However, compared with both the CABG (coronary artery bypass grafting) and ICU comparison groups and the healthy population sample, the frequency of the DD genotype and the D allele was markedly increased in patients with ARDS, which may show this relationship in ARDS.8 The differences may result from study object, pathogeny and the degree of disease.9, 10, 11

As shown in many reports, there were associations between ACE I/D polymorphism and prognosis of many diseases.2, 3, 12, 13, 14 Our finding also indicated the patients with the DD genotype were more emergent and had higher mortality. DD genotype was the significant independent prognostic factors for the 28-day outcome. Though cases in the study were not sufficient, the proportions of the ACE genotypes were similar to those previously reported in Chinese ethnic groups. However, due to a relatively small proportion of people carrying the DD genotype in the general population among Asian people, more cases may be required.

To investigate the underlying mechanism for improved outcome, we focus on the diverse effect of gene expression and enzyme activity in LPS-induced PBMC in-vitro. LPS is an effective activator which may increase ACE mRNA expression and ACE activity in all genotypes. Among the three genotypes, PBMC of DD genotype has the highest level after exposure to LPS. It may be the pathway triggered due to ACE polymorphism. It is well known that the renin-angiotensin system play an important role in inflammation. AT has a pro-inflammatory effect for the development or aggravation of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. ACE I/D polymorphism had been shown to be associated with injury to lung tissue in severe acute respiratory syndrome.15 Moreover, ACE plays a major role in the host defense against invading pathogens.16 It is therefore that polymorphisms in the ACE gene may have an important effect on determining the development and the outcome of ALI.

Conclusions

ACE I/D polymorphism is a significant prognostic factor for the outcome of ALI. Patients with the DD genotype have a higher mortality rate of ALI. I/D polymorphism influences the expression of ACE gene in LPS-stimulated PBMC, and DD genotype leads to higher level of ACE mRNA and ACE activity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this study declare that have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436(7047):112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamzik M., Frey U., Sixt S. ACE I/D but not AGT (-6) A/G polymorphism is a risk factor for mortality in ARDS. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(3):482–488. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerng J.S., Yu C.J., Wang H.C. Polymorphism of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene affects the outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4):1001–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206107.92476.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L., Feng Y., Zhang Y. Prolylcarboxypeptidase gene, chronic hypertension, and risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(1):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pera J., Slowik A., Dziedzic T. ACE I/D polymorphism in different etiology of ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114(5):320–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekerli E., Katsanidis D., Vavatsi N. ACE gene insertion/deletion polymorphism and renal scarring in children with urinary tract infections. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(10):1975–1980. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villar J., Flores C., Perez-Mendez L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is not associated with susceptibility and outcome in sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(3):488–495. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall R.P., Webb S., Bellingan G.J. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is associated with susceptibility and outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):646–650. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogulu O., Onay H., Uzunkaya D. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphisms in children with sepsis and septic shock. Pediatr Int. 2008;50(4):477–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao P., Ling Z., Woo K. Renin-angiotensin system-related gene polymorphisms are associated with risk of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2010;160(3):496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y.G., Li X.B., Zhang J. The I/D polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and asthma risk: a meta-analysis. Allergy. 2010;29 doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02438.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1398–9995.2010.02438.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Garde E.M., Endeman H., Deneer V.H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymophism and risk and outcome of pneumonia. Chest. 2008;133(1):220–225. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pabst S., Theis B., Gillissen A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme I/D polymorphism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(Suppl. 4):177–181. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-S4-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funada A., Konno T., Fujino N. Impact of renin-angiotensin system polymorphisms on development of systolic dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2010;74(12):2674–2680. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoyama S., Keicho N., Quy T. ACE1 polymorphism and progression of SARS. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2004;323(3):1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namath A., Patterson A.J. Genomic polymorphisms in sepsis. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25(4):835–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]