Graphical abstract

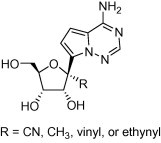

A series of 1′-substituted analogs of 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleoside were prepared and evaluated for the potential as antiviral agents. These compounds showed a broad range of inhibitory activity against various RNA viruses. In particular, the whole cell potency against HCV when R = CN was attributed to inhibition of HCV NS5B polymerase and intracellular concentration of the corresponding nucleoside triphosphate.

Keywords: C-nucleoside, Antiviral, Polymerase inhibitor

Abstract

A series of 1′-substituted analogs of 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleoside were prepared and evaluated for the potential as antiviral agents. These compounds showed a broad range of inhibitory activity against various RNA viruses. In particular, the whole cell potency against HCV when R = CN was attributed to inhibition of HCV NS5B polymerase and intracellular concentration of the corresponding nucleoside triphosphate.

Structural modification of natural N-nucleosides on either the sugar or the base has led to the discovery of a variety of therapeutic agents, which includes antivirals and anticancer agents. This approach has been continuously employed to further identify agents with improved efficacy and safety over existing drugs, overcome issues associated with drug-resistance, and expand into new therapeutic areas.1

Among all the conceivable modifications of the sugar moiety, incorporation of a substitution at 1′-position of the N-nucleosides has been rarely exploited in drug discovery.2 This is partly due to the chemical instability induced by the 1′-substituent (i.e., ready dissociation of the base and the sugar at lower pH). For example, 1′-C-Me adenosine is rapidly degraded in aqueous solutions at pH <7.3 However, C-nucleoside, in which the sugar and the base are linked through the C–C bond, should be hydrolytically stable even with a 1′-substituent. Thus, we envisioned that C-nucleoside could be an ideal scaffold to explore various 1′-substituted nucleosides for their therapeutic potential.

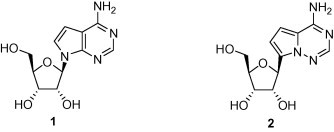

As part of an on-going effort to identify new antiviral agents, we were interested in investigating 1′-substiuted nucleosides as inhibitors of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Such nucleoside inhibitors should be converted by intracellular kinases to the triphosphorylated nucleosides, which then function as competitors of the natural nucleoside triphosphates (TP) in RNA synthesis. 7-Deazaadenosine (1, Tubercidin) is a naturally occurring, cytotoxic N-nucleoside. It is triphosphorylated inside the cells and then incorporated into RNA by host RNA polymerases, which is believed to be the main mode of action for the observed cytotoxicity.4 A C-nucleoside analog of 1, 4-aza-7.9-dideazaadenosine (2) has shown equally potent cytotoxicity to cancer cell lines.5 The TP of 2 was also shown to be a substrate of host RNA polymerases and incorporated into RNA (unpublished results). Thus, we chose compound 2 as a template to investigate the effect of the 1′-substituent on antiviral activity and selectivity. Here, we report (1) preparation of a series of novel 1′-substituted analogs of compound 2, (2) their antiviral activities against a panel of RNA viruses, and (3) correlation of the observed anti-HCV potency with both intrinsic enzyme (HCV NS5B) activity and intracellular level of the corresponding TP.

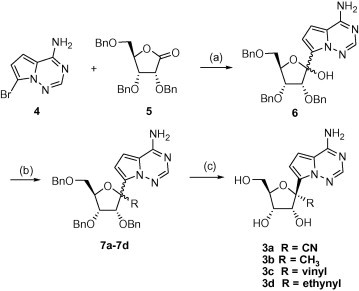

Compounds 3a–3d were prepared from a common intermediate 6, which was obtained from coupling of the bromo heterocycle 4 6 with the ribonolactone 5 (Scheme 1 ).7 The resulting hemiketal 6 was reacted with TMSCN and AlMe3 in the presence of BF3–Et2O affording compounds 7a (R = CN) and 7b (R = Me), respectively,7 while with vinyl magnesium bromide and ethynyl magnesium chloride followed by dehydrative ring closure with methanesulfonic acid providing compounds 7c (R = vinyl) and 7d (R = ethynyl), respectively.8 These products were obtained as mixtures of the two stereoisomers at the 1′-position. Subsequent debenzylation using BCl3 provided, after chromatographic separation of the two isomers, the desired nucleosides 3a–3d.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1,1,4,4-tetramethyl-1,4-dichlorodisilylethylene (1.2 equiv), NaH (2.2 equiv, 60% mineral oil), n-BuLi, (3.3 equiv), THF, −78 °C followed by addition of 5, 1 h, 60%; (b) TMSCN (4 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (3 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 5 h, 58% (85:15 β/α) 7a; AlMe3 (5 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (4 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 12 h, 45% (1:1 β/α) 7b; vinyl magnesium bromide (6 equiv), THF, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, and then methanesulfonic acid (cat.), CH2Cl2, rt, 3 h, 85% (1:1 β/α) 7c; ethynyl magnesium chloride (6 equiv), THF, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, and then methanesulfonic acid (cat.), CH2Cl2, rt, 3 h, 65% (2:1 β/α) 7d; (c) BCl3 or BBr3(4–8 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h.

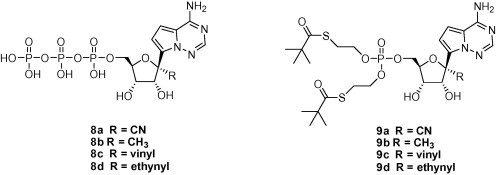

In addition, the TP derivatives (8a–8d) and bis-(SATE) monophosphate prodrugs (9a–9d) of these C-nucleosides were also prepared according to published methods.9, 10

The synthesized nucleosides 3a–3d were evaluated in cell-based assays against a panel of RNA viruses.11 Anti-HCV activity was obtained using a subgenomic replicon. Viruses tested included representatives of Flaviviridae (HCV, YFV, DENV-2, WNV), Orthomyxoviridae (influenza A), Paramyxoviridae (parainfluenza 3), Picornaviridae (Coxsackie A), and Coronaviridae (SARS-CoV). Antiviral activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50 for host cells in each assay) are shown in Table 1 . Compound 3a (R = CN) displayed broader spectrum activity (HCV, YFV, DENV-2, Influenza A, Parainfluenza 3 and SARS-CoV). Compounds 3b and 3c showed a reduced potency and a narrower spectrum of antiviral activity, and 3d no activity. While exhibiting various levels of antiviral activities, these 1′-substituted nucleosides exerted little or no cytotoxicity.

Table 1.

Antiviral activity of 1′-substituted 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleosides

| EC50/CC50 (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | |

| HCV (1b)a | 4.1/>89 | 39/>45 | >89/>89 | >89/>89 |

| YFV | 11/>30 | ND | ND | ND |

| DENV-2 | 9.46/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 |

| WNV | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 |

| Influenza A | 27.9/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 1.71/>30 | 5.23/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 |

| SARS-CoV | 2.24/>30 | >30/>30 | 14.0/>30 | >30/>30 |

| Coxsackie A | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 | >30/>30 |

HCV subgenomic replicon.

We then investigated to see if the observed antiviral activity was derived from inhibition of viral RNA dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp). Since readily available, the HCV RdRp was used to determine an enzyme inhibitory activity of TP 8a–8d. Under the established protocol,12 the IC50 values were obtained (Table 2 ). These studies revealed a good correlation between the intrinsic enzyme activity and the whole cell HCV potency. For example, compound 3a showed the most potent anti-HCV activity (EC50 of 4.1 μM), and its TP derivative (8a) the most potent inhibitory activity against the enzyme (IC50 of 5.6 μM).

Table 2.

HCV replicon activity, TP formation of nucleosides and their SATE prodrugs, and inhibition of RdRp by respective TPs

| Nucleoside |

SATE prodrug |

TP RdRp IC50 (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50/CC50 (μM) | TP concentrationa (pmol/million) | EC50/CC50 (μM) | TP concentrationa (pmol/million) | ||

| 3a/9a | 4.1/>89 | 17.6 (8a) | 0.085/3.2 | 4,220 (8a) | 5.6 μM (8a) |

| 3b/9b | 39/>89 | 50.8 (8b) | 0.078/0.73 | ND | 20 μM (8b) |

| 3c/9c | >89/>89 | 2.0 (8c) | 3.43/12 | 440 (8c) | 178 μM (8c) |

| 3d/9d | >89/>89 | 0.66 (8d) | 6.01/26 | 150 (8d) | 232 μM (8d) |

Cmax of intracellular TP (pmol/million cells) upon incubation of 10 μM of nucleosides or prodrugs in Huh-7 cells for 24 h.13

To gain further insights into the mode of the antiviral activity, bis-(SATE) monophosphate prodrugs were tested in the HCV replicon assay. In addition, intracellular levels of the TPs were measured upon incubation of these prodrugs with replicon cells,13 and compared with those from the parent nucleosides. The results are summarized in Table 2. The prodrugs 9a and 9b showed markedly enhanced replicon activity when compared to the parent nucleosides. These monophosphate prodrugs afforded >100-fold higher levels of the TP species than the parent nucleosides. Corresponding to the increased potency, an increase in cytotoxicity was also observed for the 4 prepared prodrugs. The selectivity indices (CC50/EC50) of 9b, 9c and 9d were less than 10-fold making it difficult to differentiate HCV activity from cellular toxicity. The greater potency and selectivity observed for 9a (EC50 of 0.085 μM and selectivity of 40-fold) likely reflects a combination of the potent enzyme activity and the high intracellular TP concentration (4220 pmol/million cells when cells were incubated with 10 μM of 9a). Further structural modification to improve the selectivity of 3a and 9a is warranted.

In summary, a series of novel 1′-substituted analogs of 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleoside were prepared and tested in in vitro antiviral assays. These compounds showed a broad range of antiviral activity. In particular, the HCV potency of 3a and its bis(SATE) prodrug 9a in the whole cell replicon assay were correlated with the intrinsic enzyme activity and the intracellular levels of the corresponding TP (8a), which suggests that the antiviral activity is in part derived from inhibition of RdRp. The current work establishes the potential of 1′-substituted nucleosides as antiviral agents.

References and notes

- 1.Cihlar T., Ray A.S. Antivir. Res. 2010;85:39. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Robak T. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2011;20:343. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.554822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franchetti P., Cappellacci L., Pasqualini M., Petrelli R., Vita P., Jayaram H.N., Horvath Z., Szekeres T., Grifantini M. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4983. doi: 10.1021/jm048944c. Sporadic examples of 1′-substituted N-nucleosides prepared for biological evaluation; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Damont A., Dukhan D., Gosselin G., Payronnet J., Storer R. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:1431. doi: 10.1080/15257770701542165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yoshimura Y., Kano F., Miyazaki S., Ashida N., Sakada S., Haraguchi K., Itoh Y., Tanaka H., Miyasaka T. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 1996;15:305. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappellacci P., Barboni G., Palmieri M., Pasqualini M., Grifantini M., Costa B., Martini C., Franchetti P. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:1196. doi: 10.1021/jm0102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen D.B., Eldrup A.B., Bartholomew L., Bhat B., Bosserman M.R., Ceccacci A., Colwell L.F., Fay J.F., Flores O.A., Getty K.L., Grobler J.A., LaFemina R.L., Markel E.J., Migliaccino G., Prhavc M., Stahlhut M.W., Tomassini J.E., MacCoss M., Hazuda D.J., Carroll S.S. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3944. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3944-3953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil S.A., Otter B.A., Klein R.S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:5339. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O′Connor, S.J.; Dumas, J.; Lee, W.; Dixon, J.; Cantin, D.; Gunn, D.; Burke, J.; Phillips, B.; Lowe, D.; Shelekhin, T.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Ying, S.; Mcclure, A.; Achebe, F.; Lobell, M.; Ehrgott, F.; Iwuagwu, C.; Parcella, K. WO200756170, 2007.

- 7.Metobo S.E., Xu J., Saunders O.L., Butler T., Aktoudianakis E., Cho A., Kim C.U. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:484. Our work on practical synthesis of Lewis-acid promoted 1′-substitution reactions was recently reported; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asbun W., Binkley S.B. J. Org. Chem. 1968;33:140. Analogy to. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillerman I., Fischer B. Nucleos. Nucleot. Nucleic Acids. 2010;29:245. doi: 10.1080/15257771003709569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefebvre I., Perigaud C., Pompon A., Aubertin A.-M., Girardet J.-L., Kirn A., Gosselin G., Imbach J.-L. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:3941. doi: 10.1021/jm00020a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.All virus EC50 values were measured in cytoprotection effect (CPE) assays. Cytoprotection and compound cytotoxicity are assessed by MTS (CellTiter®96 Reagent, Promega, Madison WI) dye reduction. The West Nile virus CPE assay uses Vero cells and WNV strain NY-99. The Dengue Virus CPE assay uses Vero E6 cells and Dengue Virus Type 2 strain New Guinea C. The Yellow Fever CPE assay uses HeLa cells and Yellow Fever Virus strain 17D. The Coxsackie A virus CPE assay uses MRC-5 cells and Coxsackie A strains A7 or A21. The Parainfluenza CPE assay uses Vero cells and Parainfluenza 3 strain C 243. The Influenza A CPE assay uses MDCK cells and H3N2 strain virus. The SARS-CoV CPE assay uses Vero cells and SARS-CoV strain Toronto-2.

- 12.Inhibition of NS5B was studied using GT1b NS5B recombinant protein. All concentrations are final concentration. In a solution containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 unit/μL RNAsin (Promega), and 0.01% BSA, 75 nM NS5B was pre-incubated with 4 ng/μL (50 nM) heteropolymer RNA template (sshRNA) at rt for 5 min, followed by the addition and incubation of the inhibitors at RT for 5 min. The reaction was started by addition of a mixture of ATP (3 μM), 0.03 μM 33-P-labeled ATP (Perkin–Elmer, NEG603H, 3000 Ci/mmol, 3.3 μM), and 500 μM for GTP, CTP, and UTP. After 90 min incubation at 30 °C, the reaction mixture was spotted on DE-81 filter paper and washed with 0.125 mM Na2HPO4 (3×), distilled water (1×), and reagent ethanol (1×). The filter paper was air-dried and exposed to phosphoimager (Typhooh, GE) and the data was analyzed using ImageQuant software (GE).

- 13.Durand-Gasselin L., Van Rompay K.K., Vela J.E., Henne I.N., Lee W.A., Rhodes G.R. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:1145. doi: 10.1021/mp900036s. Replicon cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing glutamax supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin–streptomycin, and G418 disulphate salt solution. Cells were transferred to 12-well tissue culture treated plates by trypsonization and grown to confluency (0.88 × 106 cells/well). Cells were treated for 24 h with 10 μM compound. Following 24 h, cells were washed 2 times with 2.0 mL ice cold 0.9% sodium chloride saline. Cells were then scraped into 0.5 mL 70% methanol and frozen overnight to facilitate the extraction of nucleotide metabolites. Extracted cell material in 70% methanol was transferred into tubes and dried. After drying, samples were re-suspended in 1 mM ammonium phosphate pH 8.5. TP levels were quantitated using liquid chromatography coupled to triple quadrapole mass spectrometry by methods similar to those previously reported in. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]