Graphical abstract

Novel nucleosides were designed and synthesized by [3+2] cycloaddition, and showed moderate antiviral activities. The nucleosides were tested against 12 different viruses.

Keywords: HSV, Antiviral, EMCV, Cox. B3, VSV, Isoxazole, Isoxazole nucleosides, Antiviral nucleoside, [3+2] Cycloaddition

Abstract

This paper describes a simple method for synthesizing a small library of 5-isoxazol-5-yl-2′-deoxyuridines from 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine. Nitrile oxides were generated in situ from oximes using a commercial bleaching agent; their cycloaddition with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine yielded isoxazoles possessing activity against herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, Encephalomyocarditis virus, Coxsackie B3, and vesicular stomatitis virus; these isoxazoles were, however, inactive against corona virus, influenza virus, and HIV.

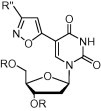

Herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) are among the most widespread viruses on Earth. HSV-1 and HSV-2 are two common strains of the herpes virus family, Herpesviridae. About 50–70% of young adults have HSV-1 antibodies in their blood. The persistent nature of herpes infection is the reason for the high probability of infection.1 HSVs cause oral and facial lesions in humans, beginning on the skin or mucosal epithelium. Because the resistance of HSV toward antiviral drugs is increasing, the development of new drugs possessing potent antiviral activity is very important. Acyclic nucleosides, including Acyclovir (ACV), Penciclovir, and Ganciclovir, are the largest class of compounds used as anti-herpes drugs.2 Another nucleoside drug class is the C5-modified pyrimidine nucleosides, including C5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU) and Brivudine (BVDU),3 which inhibits the action of DNA polymerases after its incorporation into the viral DNA, thereby preventing viral replication. Herdewijn’s group synthesized, from 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine, a large number of C5-heteroaromatic-substituted 2′-deoxyuridines posses- sing anti-HSV activity. In 1993, they synthesized 5-isoxazol-5-yl-2′-deoxyuridine 1 from 5-(3-oxo-propyn-l-yl)-2′-deoxy-uridine (Fig. 1 ) and hydroxylamine-O-sulfonic acid.4 The [3+2] cycloaddition is a very powerful reaction for synthesizing a diverse range of heteroaromatic five-membered rings.5

Figure 1.

C-5 isoxazole nucleosides.

Previously, we reported the use of [3+2] cycloadditions to efficiently synthesize sugar-modified isoxazole nucleosides and backbone-modified DNA.6 In this paper, we describe the synthesis of novel C5-modified nucleosides 2 through [3+2] cycloadditions.

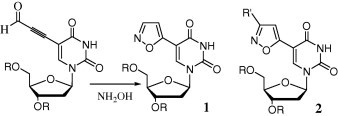

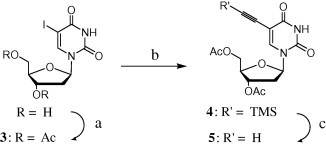

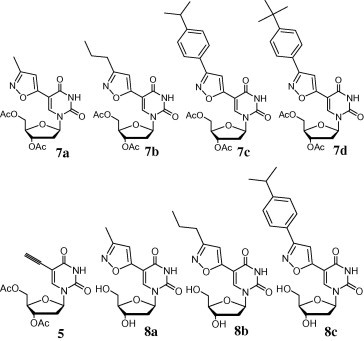

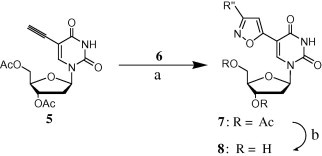

We performed [3+2] cycloadditions using a commercial bleaching agent (containing ca. 4% NaOCl) as a practical reagent for generating the nitrile oxide. As the key intermediate and dipolarophile, we synthesized the acetyl-protected 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine 5 through Sonogashira coupling (87% yield) of 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine and TMS-acetylene (See Scheme 1 ).7, 8 The oximes 6 were obtained from the reactions of several aldehydes with hydroxylamine (see Scheme 2 ). For the [3+2] cycloadditions, we employed previously established reaction conditions.6 Dropwise addition of the commercial bleaching agent provided higher yields—ranging from 59% to 77%—than did the use of reagent-grade 30% NaOCl (see Fig. 2 and Scheme 3 ).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3–5. Reagents and conditions: (a) Ac2O, pyridine, rt, 8 h; yield 92%. (b) TMS-acetylene, Pd(PPh3)4, Et3N, DMF, 40 °C, 8 h; yield 87%. (c) KF, 10% MeOH in CH2Cl2; yield 80%.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of oximes 6. Reagents and conditions: (a) HONH2·HCl, 1 N NaOH, THF (1:1), rt, 6 h; yield 90–99%.

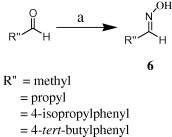

Figure 2.

Compounds tested for their antiviral properties against 12 different viruses.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 7 and 8. Reagents and conditions: (a) 4% NaOCl, THF, slow dropwise addition, rt, 10 h; yield 59–77%. (b) LiOH, MeOH/water (3:1), rt 10 h; yield 60–89%.

We investigated the antiviral activities for the various compounds against 12 different viruses, namely HSV-1, HSV-2, HIV-1, HIV-2, EMCV, Cox. B3, VSV, three different influenza viruses (Taiwan, Seoul, and Panama), and two corona viruses. The isoxazole nucleosides all exhibited anti-HSV activity. The nucleoside analogues presenting bulky R′′ groups possessed anti-herpes activity (Table 1 ). On the other hand, compound 7d 9 exhibits only HSV-2 activity. The antiviral activity for HSV-1 of 7d couldn’t be determined due to the high toxicity (CC50 = 0.06 μg/mL). The anti-herpes activities of the isoxazole nucleoside analogues are better than those of the reference drugs ACV and Cytarabine (Ara-C); for example, 8c 9 and the acetylated prodrug 7c 9 are ca. twice as active against HSV-1, and ca. 4-fold more active than ACV and 6- to 7-fold more active than Ara-C against HSV-2. Normally the acetyl groups increase the liphophilicity and support the cell penetration due to the cleavage of the acetyl groups by carboxyesterase in the cell. The 7d, one of isoxazole nucleoside analogues exhibited the best anti-HSV-2 activity: 12- and 17-fold more active than ACV and Ara-C, respectively.

Table 1.

In vitro EC50 data for HSV-1 and HSV-2 assays

| Toxicity | Antiviral activity (EC50) |

Selectivity index |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | |

| 7c | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2.03 |

| 7d | 0.06 | >0.06 | 0.03 | <1.0 | 1.81 |

| 8c | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 2.88 | 2.83 |

| ACV> | >10.00 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 55.76 | >27.78 |

| Ara-C> | >10.00 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 49.13 | >19.38 |

EC50 (μg/mL): Concentration of test compound required to inhibit virus-induced cytopaticity by 50%; CC50 (μg/mL): concentration of test compound that causes 50% cytotoxicity to uninfected cells; selectivity index: CC50/EC50.

The isoxazole nucleosides displayed anti-RNA virus activities (Table 2 ) against Coxsackie B3 (Cox. B3), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV). In the RNA virus assay, compound 8c exhibited almost the same anti-EMCV and anti-Cox. B3 potencies as that of the reference, ribavirin (Rib); compounds 7c and 7d, however, possessed 2- to 4-fold better antiviral activities against the three RNA viruses. Although some of the isoxazole nucleosides are more active than the reference drug, the bioassay results were disappointing in terms of their cytotoxicity. The selectivity indexes for the isoxazole nucleosides were lower than those of the reference drugs. None of the compounds exhibited antiviral activity against HIV, influenza, or corona viruses. In future studies, we will use the [3+2] cycloaddition strategy to synthesize different C5-triazole-substituted nucleosides from azides, rather than oximes.

Table 2.

In vitro EC data for EMCV, Cox. B3, and VSV assays

| Toxicity | Antiviral activity (EC50) |

Selectivity index |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 | EMCV | Cox. B3 | VSV | BMCV | Cox. B3 | VSV | |

| 7c | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 4.91 | 5.38 | 1.65 |

| 7d | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 5.94 | 5.30 | 1.50 |

| 8c | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | >0.07 | 3.30 | 2.76 | <1 |

| Rib. | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | >13.91 | >7.69 | >35.22 |

EC50 (μg/mL): Concentration of test compound required to inhibit virus-induced cytopaticity by 50%; CC50 (μg/mL): concentration of test compound that causes 50% cytotoxicity to uninfected cells; selectivity index: CC50/EC50.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to KOSEF (Gene Therapy R&D, KNRRC, and NCRC programs) for financial support. We thank Dr. J.K. Lee for performing the antiviral bioassay at KRICT.

References and notes

- 1.Bloom D.C., Devi-Rao G.B., Hill J.M., Stevens J.G., Wagner E.K. J. Virol. 1994;68:1283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1283-1292.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Clercq E. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1297. doi: 10.1021/jm040158k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Bergstrom D.E., Ruth J.L., Reddy P.A., De Clercq E. J. Med. Chem. 1984;27:279. doi: 10.1021/jm00369a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Clercq E., Descamps J., Verheht G., Walker R.T., Jones A.S., Torrence P.F., Shugar D. J. Infect. Dis. 1980;141:563. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cheng Y.C., Grill S., Ruth J.L., Bergstrom D.E. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980;18:957. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Creuven I., Evrard C., Olivier A., Evrard G., Van Aerschot A., Wigerinck P., Herdewijn P., Durant F. Antiviral Res. 1996;30:63. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00838-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wigerinck P., Pannecouque C., Snoeck R., Claes R., De Clercq E., Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2383. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wigerinck P., Kerremans L., Claes P., Snoeck R., Maudgal J.P., De Clercq E., Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:538. doi: 10.1021/jm00057a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Cecchi L., De Sarlo F., Machetti F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:4852. [Google Scholar]; (b) Himo F., Lovell T., Hilgraf R., Rostovtsev V.V., Noodleman L., Sharpless K.B., Fokin V.V. J. Am. Chem. 2005;127:210. doi: 10.1021/ja0471525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Lee Y.-S., Kim B.H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:1395. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim S.J., Lee J.Y., Kim B.H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:1313. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kong J.R., Kim S.K., Moon B.J., Kim S.J., Kim B.H. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:1751. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100107187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Park S.M., Lee Y.S., Kim B.H. Chem. Commun. 2003:2912. doi: 10.1039/b311249g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuigan C., Yarnold C.J., Jones G., Velazquez S., Barucki H., Brancale A., Andrei G., Snoeck R., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2275. doi: 10.1021/jm990346o. (a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Cristofoli W.A., Wiebe L.I., De Clercq E., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Balzarini J., Knaus E.E. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2851. doi: 10.1021/jm0701472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Terrence P.F., Spencer J.W., Bobst A.M., Descamps J., De Clercq E. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:228. doi: 10.1021/jm00200a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Robins M.J., Manfredini S., Wood S.G., Wanklin R.J., Rennie B.A., Sacks S.L. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2275. doi: 10.1021/jm00111a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selected spectroscopic data.5: 1H NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 10.34 (br, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 6.24 (t, J = 7.20 Hz, 1H), 5.31–5.27 (m, lH), 4.35–4.29 (m, 3H), 2.51–2.47 (m, 2H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 2.03–2.01 (m, 1H).Compound 7a: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.37 (br, 1H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.35 (t, J = 6.77 Hz, 1H), 5.35 (br, 1H), 4.46–4.39 (m, 2H), 4.38–4.35 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.54 (m, 2H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.10 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.0, 171.8, 163.6, 162.0, 161.3, 151.0, 139.5, 126.3, 105.1, 104.4, 87.5, 84.4, 76.1, 65.4, 39.2, 21.4, 21.3, 11.8; MS (EI+) m/z 393.12, calcd 393.096.Compound 7b: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.30 (br, 1H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 6.39 (t, J = 5.71 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (d, J = 6.32 Hz, lH), 4.46–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.33–4.28 (m, 2H), 2.66–2.61 (m, 2H), 2.53–2.51 (m, 1H), 2.32–2.29 (m, 1H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.8, 170.5, 165.2, 161.1, 159.1, 149.1, 137.4, 126.3, 105.1, 101.3, 85.9, 83.3, 74.6, 64.1, 38.8, 28.3, 21.9, 21.2, 21.1, 14.0; MS (EI+) m/z 421.15, calcd 421.149.Compound 7c: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.85 (br, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.21 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.08 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (s, 1H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 6.41 (t, J = 5.62 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (s, lH), 4.42–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.36–4.32 (m, 2H), 2.90–2.85 (m, 1H), 2.54–2.48 (m, 1H), 2.26–2.23 (m, 1H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.18 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 170.4, 163.4, 161.7, 159.1, 151.5, 149.1, 137.4, 127.2, 126.6, 104.9, 101.5, 86.0, 83.2, 74.5, 64.0, 38.7, 34.3, 21.1, 21.0; MS (EI+) m/z 497.18, calcd 497.180.Compound 7d: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.95 (br, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.19 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.09 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 6.41 (t, J = 5.76 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (s, 1H), 4.47–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.36–4.32 (m, 2H), 2.57–2.53 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.33 (m, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 170.4, 163.4, 161.7, 159.1, 151.5, 149.1, 137.4, 127.2, 126.6, 104.9, 101.5, 86.0, 83.2, 74.5, 64.0, 38.7, 34.3, 21.1, 21.0; MS (EI+) m/z 511.20, calcd 511.195.Compound 8c: 1H NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.90 (br, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.27 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 6.37 (t, J = 6.59 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (s, 1H), 4.57–4.54 (m, 21H), 4.51–4.49 (m, 1H), 4.05–4.03 (m, 1H), 3.90–3.87 (m, 2H), 2.98–2.91 (m, 1H), 2.41–2.37 (m, 2H), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 170.4, 163.4, 161.7, 159.1, 151.5, 149.1, 137.4, 127.2, 126.6, 104.9, 101.5, 86.0, 83.2, 74.5, 64.0, 38.7, 34.3, 21.1, 21.0; MS (EI+) m/z 413.16, calcd 413.159.