Highlights

-

•

Colostrum uptake is important for early establishment of lactogenic immunity.

-

•

Neutralizing activity in milk and colostrum is associated with anti-spike IgA.

-

•

Sow milk is a continuous supply of IgA with neutralizing activity.

-

•

Temporal patterns of neutralizing antibody production in milk are variable.

Keywords: PEDV, Neutralizing activity, Colostrum and milk, Dynamics, Anti-PEDV IgA, Correlation

Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) causes a severe clinical enteric disease in suckling neonates with up to 100% mortality, resulting in devastating economic losses to the pork industry in recent years. Maternal immunity via colostrum and milk is a vital source to neonates of passive protection against diarrhea, dehydration and death caused by PEDV. Comprehensive information on neutralizing activity (NA) against PEDV in mammary secretions is critically important for assessing the protective capacity of sows. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to characterize anti-PEDV neutralizing activity in mammary secretions. Anti-PEDV NA was present in colostrum, milk and serum from PEDV-infected sows as determined both by immunofluorescence and ELISA-based neutralizing assays, with neutralization levels higher in colostrum and milk than in serum. The highest NA was observed in colostrum on day 1, and decreased rapidly in milk at day 3, then gradually declined from day 3 to day 19 post-farrowing. Notably, the NA in mammary secretions showed various patterns of decline over time of lactation that may contribute to variation in sow protective capacities. The kinetics of NA decline were associated with total IgA and IgG antibody levels. Neutralizing activity significantly correlated with specific IgA primarily to spike domain 1 (S1) and domain 2 (S2) proteins of PEDV rather than to specific IgG in colostrum. Subsequently, the NA in milk was mainly related to specific IgA to S1 and S2 during lactation.

1. Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED), an acute and highly contagious enteric disease, is characterized by watery diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, and high mortality in sucking piglets, especially in 7–10-day-old piglets (Li et al., 2012, Pijpers et al., 1993). The disease was first recorded in England in 1971 and spread to other European and Asian countries (Li et al., 2012, Park et al., 2013, Wood, 1977). Since late 2010, PED prevalence with high morbidity (90–100%) and mortality (70–100%) in suckling pigs has become more clinically frequent, and more severe than the historical clinical symptoms in China (Chen et al., 2011, Li et al., 2012, Yang et al., 2013). The outbreaks of PED suddenly occurred in April 2013 and spread through the pork industry across the United States (US) (Anon, 2014, Chen et al., 2014, Cima, 2013, Stevenson et al., 2013, Vlasova et al., 2014).

PEDV, a member of the genus Alphacoronavirus within the family Coronaviridae, is a positive-sense single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus (Pensaert and de Bouck, 1978). The 28 kb genome encodes four major structural proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) (Kocherhans et al., 2001, Song and Park, 2012). The S protein of PEDV can be divided into domain 1 (S1) and domain 2 (S2) (Lee et al., 2010, Oh et al., 2014). It is a pivotal surface glycoprotein involved in virus attachment, entry and induction of neutralizing antibodies in the natural host (Cruz et al., 2008, Sun et al., 2008). The N protein is the most abundant viral protein in infected cells, is associated with the viral RNA genome, and may be important for induction of cell-mediated immunity (CMI) (Saif, 1993).

PEDV causes severe enteric disease in suckling pigs, but milder disease in older weaned pigs (Annamalai et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2014, Madson et al., 2014, Stevenson et al., 2013), similar to another enteric coronavirus, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) (Moon et al., 1973, Norman et al., 1973). Therefore, maternal vaccines to induce lactogenic immunity and their transmission to suckling neonates via colostrum and milk are pivotal for early passive protection (Chattha et al., 2015, Wesley and Lager, 2003). Inoculations with PEDV virulent isolates, killed or attenuated strains induce specific mucosal and systemic immune responses in sows (Goede et al., 2015, Ouyang et al., 2015). The specific neutralizing antibodies (NA) were presented in colostrum, milk and serum after attenuated PEDV was orally or intramuscularly administered to late-term pregnant sows (Kweon et al., 1999, Ouyang et al., 2015). Lactogenic immunity, based on the presence of specific NA, can decrease the mortality of neonatal piglets or prevent death after challenge with wild-type PEDV (Goede et al., 2015, Kweon et al., 1999, Song et al., 2007).

Considering that maternal antibody plays pivotal roles in protecting neonates from enteric infections, we characterized neutralizing activity against PEDV in colostrum, milk and serum of sows after farrowing, the dynamics of the neutralizing activity in milk during lactation, and correlations between the neutralizing activity and specific antibodies to PEDV-S1, -S2 and -N proteins.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and virus

Vero-81 cells were cultured in complete medium containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (Sigma), and 50 μg/mL gentamycin sulfate (Lonza) in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM, Sigma) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. PEDV strain 13-019349 (Genbank ID: KF267450), isolated from PEDV-infected fecal samples at the National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames IA, was propagated in Vero-81 cells with complete medium containing 2.5 μg/mL trypsin, and 10% tryptose phosphate broth solution (Sigma). Removal of trypsin from the maintenance media resulted in reduced infection, as reported previously (Li et al., 2012). Virus stocks of 2.54 × 105 TCID50/mL or 1.4 × 1010 viral genome copies per mL were collected and stored at –80 °C until use.

2.2. Sample collection

A midwestern United States sow farm was diagnosed with a PEDV outbreak and a planned exposure event occurred while weaned piglets were testing positive for PEDV by PCR. The planned exposure inoculum was prepared by humanely sacrificing piglets clinically affected with acute diarrhea, collecting intestinal contents and diluting in water. Two months after exposure of the entire herd, all weaned pigs tested negative for PEDV. Colostrum, milk and serum samples were collected from sows beginning one month later. Colostrum was harvested by hand massage within 24 h and milk at or after 3 days post-farrowing. Serum was collected by venipuncture in serum-separator tubes. PEDV antibody-negative colostrum, milk and serum was collected from sows at a farm without PEDV infection.

Colostrum and milk were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with 2.5 μg/mL rennet. The clear fluid was harvested and heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56°. Alternatively, samples were refrigerated for 3 days to obtain an aqueous fraction that was heat-treated. Serum also was heat-inactivated. The treated samples were used immediately or stored at –40 °C prior to testing.

2.3. Antigen production

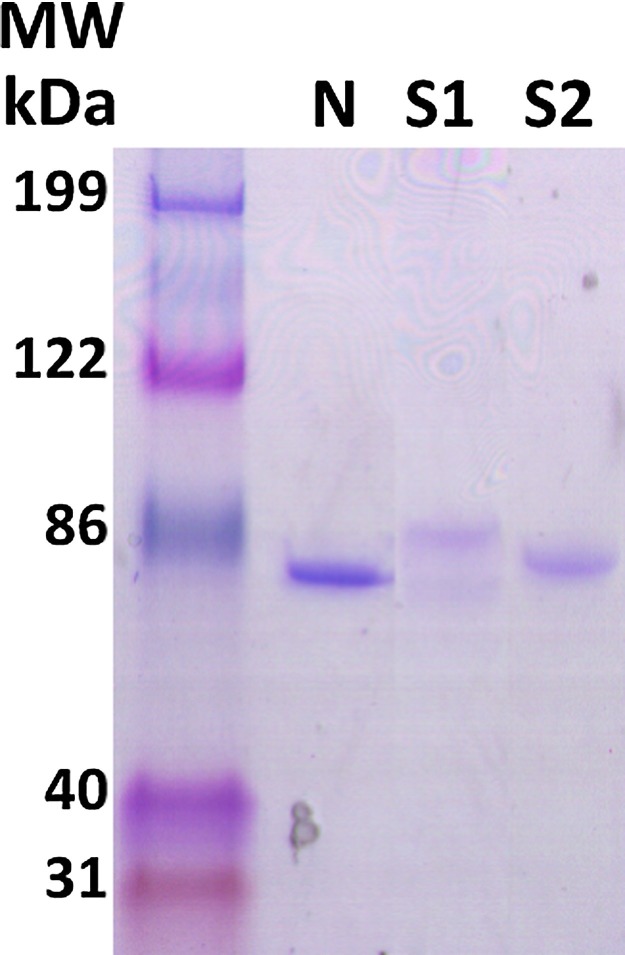

PEDV RNA was extracted from a fecal sample containing isolate USA/Colorado/2013 (Genbank accession KF272920). PCR amplicons were obtained that contained open reading frames encoding N (sequence 26382-27701), S1 (sequence 20694-22844) and S2 (sequence 22860-24614). Amplicons were inserted into the pET25b vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) by In-Fusion cloning (TaKaRa) and transformed into E. coli for expression and purification as previously described (Dvorak et al., 2016, Johnson et al., 2007, Puvanendiran et al., 2011). Inserts of recombinant plasmids were sequenced to confirm their identities. Recombinant protein quality was assessed by SDS-gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

SDS polyacrylamide gel containing purified N, S1 and S2. Bands were visualized with Imperial protein stain (Thermo Scientific). The molecular weight standards were Kaleidoscope prestained proteins (BioRad). The predicted molecular weight of N is about 55 kD, but it runs anomalously on SDS gels.

2.4. ELISA

96-well plate wells (Corning, NY) were coated with 0.1 μg of recombinant PEDV proteins, S1, S2 or N, in 50 mM carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), and incubated at 4° C overnight. Plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) at room temperature (ELx405 Microplate Washer, Bio-Tek Instrument Inc.). Blocking buffer (PBST with 5% non-fat dry milk) was added for 2 h, washed, and diluted samples (colostrum, milk or serum) and negative control (1:50) were added in duplicate for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-pig IgG (Bethyl Labs) diluted 1:100 000, was added for 1 h. After plates were washed, tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate with H2O2 was added to each well to develop in the dark for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 1 M phosphoric acid. Optical density (OD) was measured with an ELISA-spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek) at 450 nm.

Total IgG and IgA antibody levels in milk were determined by isotype-specific ELISA using a standard curve (Bethyl Laboratories). In brief, diluted coating antibody (IgG or IgA) was added to each well for 1 h. Serially two-fold diluted standards and samples in duplicate were added and incubated for 1 h. After washing, HRP-conjugated detection antibody was added and incubated as described. Plates were washed and TMB Substrate Solution was added to each well. Plates were developed in the dark for 15 min and reactions stopped with phosphoric acid as described. Absorbance was measured on the plate reader at 450 nm. The IgG or IgA concentration was calculated in unknown samples using the standard curve.

2.5. Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for neutralization activity

The colostrum, milk and serum were two-fold serially diluted in maintenance media and incubated with an equal volume of PEDV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 1 h at 37 °C. One hundred μL of the sample-virus mixture was transferred to duplicate wells containing confluent Vero-81 cells in 96-well plates. Samples (colostrum, milk or serum), virus and blank controls were prepared at the same time. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, washed gently, and pre-warmed maintenance media was added. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Plates were washed and fixed using ice-cold absolute methanol for 10 min at –20 °C. The methanol was removed, wells washed, and anti-PEDV N protein monoclonal antibody (SD6-29, Medgene Labs) was added at a dilution of 1:1000 for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were washed and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Bethyl Laboratories) (1:1000) was then added and incubated for 45 min at 37 °C. Plates were washed and cells were stained with bisbenzimide (10 ng/mL) for 20 min and washed. The plates were examined and images were captured under an Olympus 1X70 inverted fluorescence microscope.

2.6. ELISA-based neutralizing assay

The PEDV serum neutralization (SN) assay was performed essentially as described and explained (Li and Murtaugh, 2012, Robinson et al., 2013). Milk and colostrum samples were serially diluted and incubated with PEDV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 1 h at 37 °C. Confluent Vero-81 cell monolayers in 96-well plates were washed with PBS before mixtures of sample and virus, positive-control virus and blank controls were added in duplicate. After 1 h incubation at 37 °C, plates were washed and incubated at 37 °C in prewarmed media. After 24 h, plates were washed and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, washed and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 9.5, for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were treated with anti-PEDV N protein monoclonal antibody (SD6-29) (Medgene Lab, USA) diluted 1:1000 for 1 h at 37 °C, washed, and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG heavy and light chains antibody (Bethyl Laboratories, USA) diluted 1:10 000. Plates were washed with PBST and developed using TMB development solution (KPL, USA). Reactions were stopped with 1 M phosphoric acid and absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek, USA). Percent inhibition of viral infection at each dilution was compared with virus only controls after background subtraction of absorbance from uninfected cells. Fifty percent neutralization titer was defined as reciprocal of the highest serum dilution for which 50% inhibition of infection was reached.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Neutralizing antibody titers were converted into log10 and used in statistical analysis. SPSS 17.0 was employed for correlation analysis and a value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Neutralizing activities in serum, colostrum and milk

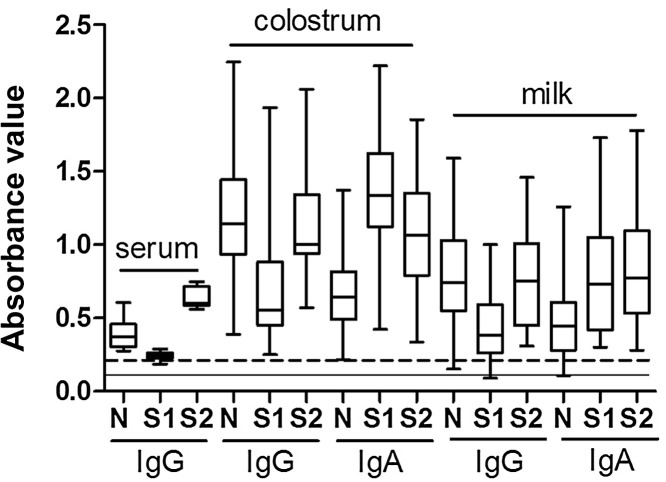

Presence of specific antibodies against PEDV-N, S1 and S2 proteins in serum, colostrum and milk confirmed that test sows were previously infected. Fig. 2 shows that the relative level of anti-S2 IgG in serum was higher and less variable than anti-N IgG, and that the level of anti-S1 IgG was near the limit of detection. Anti-PEDV IgA antibodies in serum were insignificant (data not shown). The pattern of IgG reactivity in colostrum and milk was similar to that observed in serum, though with exceeding high levels of variation, particularly in milk, in which levels of anti-N and anti-S1 were undetectable in some sows. Quantitative comparison of IgG levels in serum, colostrum and milk was not feasible since sample dilutions needed to give results within the linear absorbance range of the ELISA varied greatly. Specifically, serum was diluted from 1:3000 to 1:10,000, colostrum from 1:100,000 to 1:1,000,000, and milk from 1:3000 to 1:250,000. Anti-PEDV IgA results differed notably from IgG results, with anti-S1 IgA most abundant in colostrum and anti-N substantially lower, and in milk anti-S1 and anti-S2 IgA were both high compared to anti-N-IgA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PEDV-N, -S1 and -S2 antibodies (IgG or IgA) were examined in serum, colostrum and milk by ELISA. Serum came from sows (n = 8), colostrum from sows (n = 34) within 24 h post-farrow, and milk (n = 31) from sows at 7 days post-farrowing. ELISA analysis was performed using the nucleocapsid (N), spike domain 1 (S1), or spike domain 2 (S2). The positive/negative cutoff was 0.1 (solid line) for anti-N antibody detection, and 0.2 (dashed line) for anti-S1 and anti-S2 antibody detection.

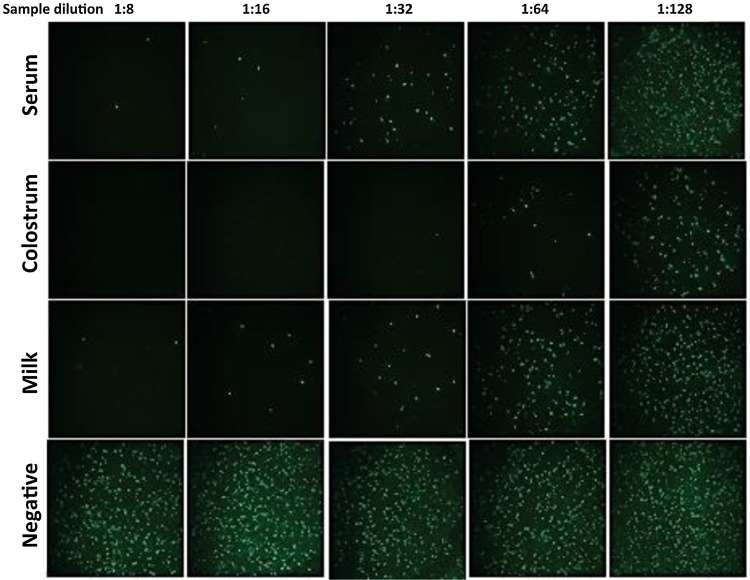

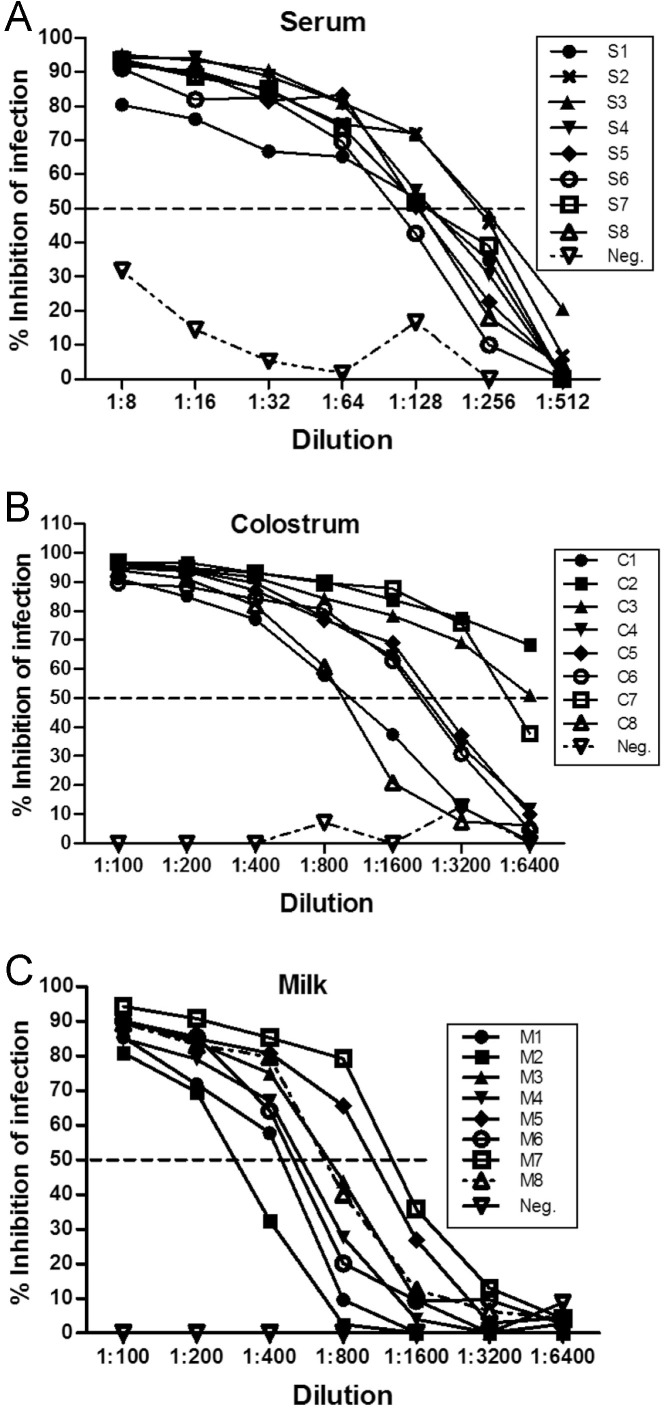

Validation of the PEDV neutralization assay in serum, colostrum and milk matrices was first established by immunofluorescent visualization of infected Vero 81 cell monolayers. Typical fluorescent images of infected monolayers are shown in Fig. 3 . Addition of serially diluted milk from a previously infected sow showed solid inhibition, even at the highest dilution of 1:128. Similarly, colostrum and serum samples showed dilution-dependent inhibitory activity (Fig. 3). The ELISA-based neutralizing assay showed that 50% inhibition of viral infection was observed in serum at a dilutions of 1:128–1:256, in colostrum at 1:1600–1:3200, but with occasional samples > 1:6400, and in milk at 1:800–1:1600 (Fig. 4 A–C). These results indicated that colostrum and milk had higher levels of PEDV neutralizing activity than were present in serum, and also showed that variation among sows was higher than would be predicted from results using serum.

Fig. 3.

PEDV-infection inhibition in serum, colostrum and milk in Vero-81 cells by the immunofluorescence assay. Colostrum was collected within 24 h post-farrowing and milk was collected on day 12 post-farrowing. Negative samples came from a healthy sow without PEDV antibodies.

Fig. 4.

Infection inhibition in serum, colostrum and milk in Vero-81 cells by ELISA-based neutralizing assay. Serum (S1–S8), colostrum (C1–C8) collected within 24 h of farrowing, and milk (M1–M8) collected on day 12 post-farrowing were analyzed. Neg. indicates negative serum, colostrum or milk not containing PEDV antibodies.

3.2. Temporal dynamics of neutralizing antibody secretion during lactation

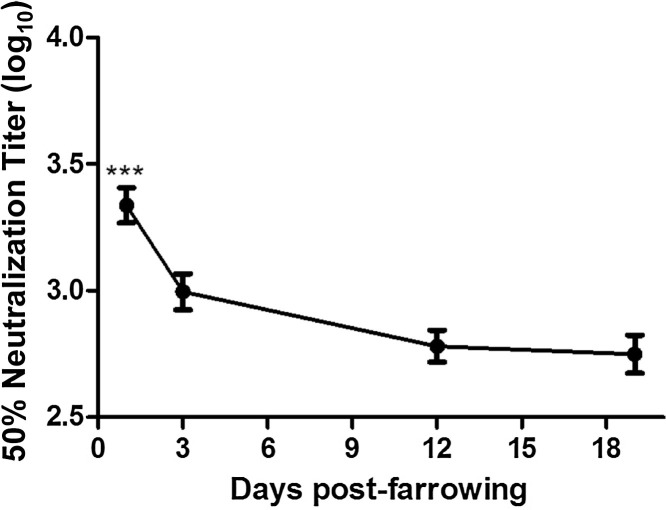

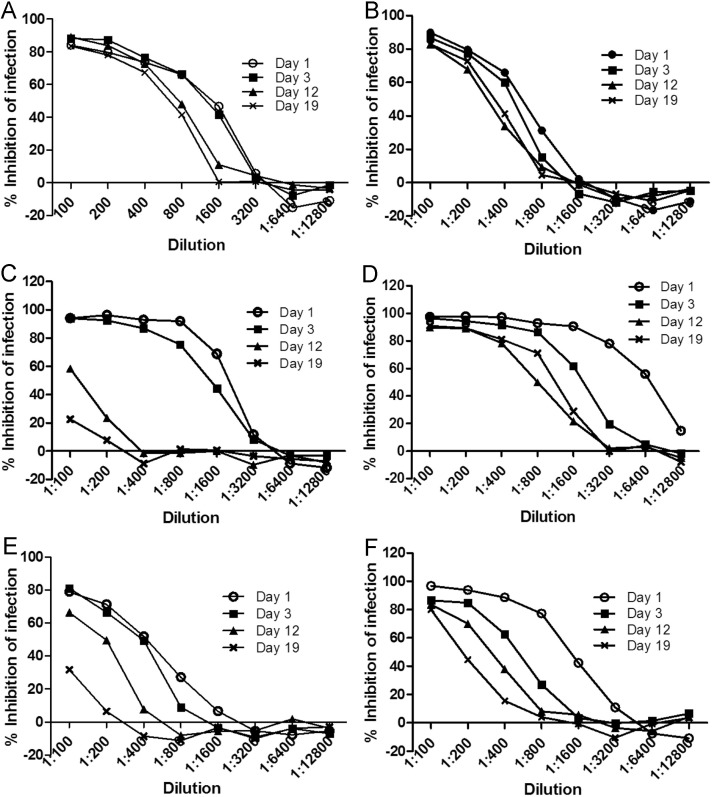

Inhibition of PEDV infection was determined in colostrum and milk secretions from 37 sows over 19 days post-farrowing. Average neutralizing antibody titer was highest in colostrum collected on day 1 compared to milk collected on days 3, 12 and 19 post-parturition (P < 0.01). Average neutralizing titer in colostrum was 1:3220, declining to 1:1000 by day 3, then declining slowly to 1:560 by day 19 (Fig. 5 and Table 1 ). However, various declining trends of neutralizing antibody in milk were exhibited among different sows over time of lactation (Fig. 6 A–F), and the neutralization of PEDV in some sows became very low by day 12 after farrowing (Fig. 6C and E).

Fig. 5.

Dynamics of neutralizing antibody titers (log10) in mammary secretions over time of lactation. Colostrum and milk were collected from PEDV-infected sows (n = 37) on days 1, 3, 12 and 19 post-farrowing. Neutralizing antibody titers were expressed as log10 at 50% inhibition of PEDV infection in Vero-81 cells and are presented as means ± SD. Asterisk indicates statistical difference between day 1 and other days (***p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Concentration of total IgG and IgA and anti-PEDV NA titers in colostrum and milka.

| Samples (n = 37) | Concentration (mg/mL) |

NA titers (Log10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgA | |||

| Colostrum | Day 1 | 25.92 ± 10.27 D | 13.39 ± 5.63 B | 3.34 ± 0.41 B |

| Milk | Day 3 | 5.15 ± 7.5C | 7.10 ± 4.41 A | 3.00 ± 0.40 Ab |

| Day 12 | 1.29 ± 1.58 B | 6.80 ± 4.30 A | 2.78 ± 039 Aa | |

| Day 19 | 0.46 ± 0.27 A | 6.85 ± 2.23 A | 2.75 ± 0.46 Aa | |

ABCD or abSuperscripts within columns indicate statistically significant differences among the days in the same columns (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05, respectively).

Colostrum and milk were collected from sows (n = 37) at various days post-farrowing. Neutralizing titers were expressed as log10 at 50% inhibition of PEDV infection in Vero-81 cells.

Fig. 6.

Various patterns of neutralizing activities in milk in Vero-81 cells by ELISA-based neutralizing assay. Milk collected on days 1, 3, 12 and 19 post-farrowing. A through F are the neutralization curves for each time point in 6 individual sows.

The dynamics of total IgG and IgA production in milk were measured from day 1 to day 19 post-farrowing by isotype-specific ELISA. Concentrations of both IgG and IgA were significantly higher in colostrum (day 1) than in milk (day 3–day 19) (p < 0.01). IgG levels continued to decline from day 3 to day 19 while IgA levels were maintained in milk at about 7 mg/mL (Table 1). These two trends were similar to that of neutralizing activity against PEDV, but the kinetics of IgA production paralleled neutralizing activity more closely than did IgG.

3.3. Correlations between neutralizing activity and antibodies to N, S1 and S2 proteins

Specific viral neutralization activity correlated significantly with specific IgA in milk to PEDV N, S1 and S2 protein rather than specific IgG at day 1 post-farrowing (Table 2 ). After day 1, the viral neutralization activity was mainly related to specific IgA to S1 and S2 over time of lactation.

Table 2.

Correlations between neutralizing activities and isotype-specific antibodies to N, S1 and S2 proteins in colostrum and milka.

| Days post-farrowing | Ig | OD450 (n = 37) | NA (Log10) (n = 37) | Correlation coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N IgG S1 IgG S2 IgG |

1.215 ± 0.398 0.701 ± 0.382 1.110 ± 0.313 |

3.337 ± 0.406 | 0.011 0.301 0.174 |

0.951 0.079 0.318 |

| 1 | N IgA S1 IgA S2 IgA |

0.679 ± 0.280 1.360 ± 0.453 1.065 ± 0.336 |

0.469 0.450 0.455 |

0.003** 0.007** 0.006** |

|

| 3 | N IgA S1 IgA S2 IgA |

0.363 ± 0.189 0.943 ± 0.385 0.610 ± 0.305 |

2.995 ± 0.399 | 0.292 0.528 0.489 |

0.111 0.002** 0.005** |

| 12 | N IgA S1 IgA S2 IgA |

0.288 ± 0.184 0.709 ± 0.328 0.496 ± 0.255 |

2.769 ± 0.386 | 0.346 0.616 0.574 |

0.039* 0.000** 0.000** |

| 19 | N IgA S1 IgA S2 IgA |

0.285 ± 0.142 0.687 ± 0.335 0.419 ± 0.208 |

2.748 ± 0.455 | 0.159 0.375 0.420 |

0.353 0.024* 0.011* |

*or ** indicated that the correlation was significant at the 0.05 or 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Colostrum (day 1) and milk (days 1, 3, 12 and 19 post-farrowing) were collected from PEDV immune sows. Correlation was performed by comparing the neutralizing titer of each sample to the antigen- and isotype-specfiic ELISA value of the sample using SPSS 17.0.

4. Discussion

Maternal antibodies from sows inoculated or infected with enteric viruses such as PEDV or TGEV are vitally important for suckling neonates to obtain early passive protection via colostrum and milk (Chattha et al., 2015, Goede et al., 2015, Wesley and Lager, 2003). Specific IgA and IgG neutralizing antibodies in serum and colostrum appeared when the late-term pregnant sows were inoculated with an attenuated PEDV orally or intramuscularly (Ouyang et al., 2015, Paudel et al., 2014, Song et al., 2007). In this study, PEDV-specific neutralizing activity found in serum, colostrum and milk exhibited various levels of neutralizing activity in which the highest inhibition was in colostrum, then in milk, and last in serum, as observed previously (Paudel et al., 2014). This result emphasizes the importance of mammary secretions to suckling neonates to obtain early passive protection from PED.

PEDV-specific antibodies were observed in serum and oral fluids in sows from 1 to 6 months after infection, and the virus neutralization titers in serum persisted beyond 6 months (Ouyang et al., 2015). However, the characteristics of PEDV-specific neutralizing antibody responses in mammary secretions have not been characterized. We show that the virus neutralizing antibody titer and the levels of total IgG and IgA in colostrum at day 1 significantly exceeded those in milk at day 3, and declined progressively from day 3 to day 19 after farrowing. Further analysis indicated that IgG levels continued to drop sharply from day 3 to day 19 while IgA declined slightly, more closely to the trend of virus neutralizing activities at the same time. This result indicated that IgA might play a more important role in virus neutralization especially after day 3 post-farrowing.

Various patterns of declining neutralizing activities were observed in sow milk over time of lactation. The various patterns of neutralizing antibody activity through lactation showed the complexity of lactogenic immunity, and might explain why feedback methods utilizing PEDV infected material have shown variable success in protection of litters from PED (R. Morrison, personal communication). It still remains a challenge to achieve uniformity of lactogenic immunity in herds against PEDV infection.

PEDV S glycoprotein (S1 and S2 domains) containing B cell neutralizing epitopes can stimulate the production of viral neutralizing antibodies (Cruz et al., 2008, Sun et al., 2008). The N protein may be important for induction of cell-mediated immunity and be able to effectively facilitate the mucosal and systemic immune responses induced by S1 protein (Liu et al., 2012, Saif, 1993). In addition, M protein plays an important role in viral assembly, and it contains a conserved linear B-cell epitope (Arndt et al., 2010, Zhang et al., 2012). Here, further analyses of the correlations of PEDV neutralizing activities and specific antibody isotypes, IgG and IgA to PEDV S1, S2 or N proteins in mammary secretions during lactation indicated that the specific anti-S1, -S2 and -N IgG did not correlate significantly with viral neutralizing activity in milk. However, the neutralizing activities were dominated by IgA to S1 and S2 proteins in colostrum on day 1 post-farrowing. Subsequently, anti-S1 and anti-S2 IgA in milk played a vital role in viral neutralization. The results demonstrated that PEDV neutralizing activities in mammary secretions, within the limitations of the proteins examined, i.e. S1, S2, and N, were correlated with specific antibodies to structural proteins of PEDV, principally anti-S1 and anti-S2 IgA, in milk.

The ELISA-based PEDV neutralization assay was used because it is a more direct measure of an effect on infection since assays based on plaque formation also depend on viral cytopathology, are more labor and time intensive, and can be affected by operator experience. The use of 50% reduction as the readout in place of a focus-forming or plaque assay with 90% reduction enables optimization of key parameters, including MOI and testing of the percentage law (Andrewes and Elford, 1933, Brioen and Boeye, 1985). The 50% endpoint for neutralization titers was used in place of 90% reduction in focus-forming units to gain information about the antibody reactivity independently of antigen concentration. Virus–antibody interactions can be modeled as antigen–antibody interactions that conform to the law of mass action as a reaction approaches equilibrium (Klasse and Sattentau, 2002, Reverberi and Reverberi, 2007, Tyrrell, 1953). Since neutralized and non-neutralized virus is in equilibrium at 50% inhibition of infectivity, mathematical modeling can be used to assess functional qualities of antibodies and antisera that have viral neutralizing activity, as has been shown in HIV, influenza virus, human adenovirus, equine infectious anemia virus, chimeric SIV/HIV, and Newcastle disease virus infections (Klasse and Moore, 1996, McEwan et al., 2012, Nishimura et al., 2002, Schwartz and Smith, 2014, Shingai et al., 2014, To et al., 2012, Tyrrell, 1953, Willey et al., 2010). Characterization of neutralization affinity, reaction kinetics, and avidity cannot be determined under more stringent conditions, such as at 90% inhibition, which are not at equilibrium. More stringent neutralization readouts may have value for diagnostic purposes or for studies in which there is background cross-reactivity such as with dengue virus (Roehrig et al., 2008). However, cross-reacting substances have not been reported to interfere with PEDV neutralization assays.

In summary, the data show that neutralizing antibody levels against PEDV are high but patterns of passive expression in colostrum and milk are variable over time in mammary secretions. Sow variability might help explain the inconsistent success of feedback methods to protect suckling neonates from clinical PED through maternal protection received from immune dams. Moreover, the kinetics of neutralizing antibody titers during lactation help explain the pivotal role of IgA in colostrum and milk in suckling neonates to gain passive protection. The amount of neutralizing antibodies necessary for protection in piglets is unknown, and would be affected by titer, volume of milk ingested, antibody stability in the enteric environment, and possibly other variables that could be difficult to measure. Neutralizing activities in mammary secretions, which can be assessed and are mainly correlated with specific IgA antibodies to PEDV spike glycoprotein, may help guide vaccine design and immunological monitoring for PEDV.

Authors’ contributions

Qinye Song performed the cell culture and neutralization experiments, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SS designed and performed the ELISA, and analyzed the data. DD collected the samples, reviewed the manuscript and assisted in data analysis. LLG conceived the study with MPM, designed and monitored the animal studies, and assisted in writing. MPM conceived the study with LLG, analyzed data, edited and finalized the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cooperative State Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under project MIN-63-112, National Pork Board grant 14-175, the China Scholarship Council and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31372441) to support QS, and Carthage Veterinary Services, Carthage, IL. DD was a DVM student in the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, sponsored by Carthage Veterinary Services on an internship. We thank Audrey Tseng, an undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota, for assistance in protein expression and purification.

References

- Andrewes C.H., Elford W.J. Observations on anti-phage sera. I. The percentage law. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1933;14(6):367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai T., Saif L.J., Lu Z., Jung K. Age-dependent variation in innate immune responses to porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection in suckling versus weaned pigs. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015;168(3–4):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anon . In: Swine Enteric Coronavirus Disease Tessting Summary Report, July 24, 2014. U.S.D.o. Agriculture, editor. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2014. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt A.L., Larson B.J., Hogue B.G. A conserved domain in the coronavirus membrane protein tail is important for virus assembly. J. Virol. 2010;84(21):11418–11428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioen P., Boeye A. Poliovirus neutralization and the percentage law. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1985;83(1–2):105–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01310968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattha K.S., Roth J.A., Saif L.J. Strategies for design and application of enteric viral vaccines. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015;3:375–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-111038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Wang C., Shi H., Qiu H.J., Liu S., Shi D., Zhang X., Feng L. Complete genome sequence of a Chinese virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain. J. Virol. 2011;85(21):11538–11539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06024-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Li G., Stasko J., Thomas J.T., Stensland W.R., Pillatzki A.E., Gauger P.C., Schwartz K.J., Madson D., Yoon K.J., Stevenson G.W., Burrough E.R., Harmon K.M., Main R.G., Zhang J. Isolation and characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses associated with the 2013 disease outbreak among swine in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52(1):234–243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima G. Viral disease affects U.S. pigs: porcine epidemic diarrhea found in at least 11 states. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013;243(1):30–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz D.J., Kim C.J., Shin H.J. The GPRLQPY motif located at the carboxy-terminal of the spike protein induces antibodies that neutralize Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Virus Res. 2008;132(1–2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak C.M.T., Yang Y., Haley C., Sharma N., Murtaugh M.P. National reduction in porcine circovirus type 2 prevalence following introduction of vaccination. Vet. Microbiol. 2016;189:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goede D., Murtaugh M.P., Nerem J., Yeske P., Rossow K., Morrison R. Previous infection of sows with a mild strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus confers protection against infection with a severe strain. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;176(1–2):161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.R., Yu W., Murtaugh M.P. Cross-reactive antibody responses to nsp1 and nsp2 of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88(Pt 4):1184–1195. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse P.J., Moore J.P. Quantitative model of antibody- and soluble CD4-mediated neutralization of primary isolates and T-cell line-adapted strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1996;70(6):3668–3677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3668-3677.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse P.J., Sattentau Q.J. Occupancy and mechanism in antibody-mediated neutralization of animal viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83(Pt 9):2091–2108. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-9-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocherhans R., Bridgen A., Ackermann M., Tobler K. Completion of the porcine epidemic diarrhoea coronavirus (PEDV) genome sequence. Virus Genes. 2001;23(2):137–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1011831902219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweon C.H., Kwon B.J., Lee J.G., Kwon G.O., Kang Y.B. Derivation of attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) as vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 1999;17(20–21):2546–2553. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.K., Park C.K., Kim S.H., Lee C. Heterogeneity in spike protein genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses isolated in Korea. Virus Res. 2010;149(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Murtaugh M.P. Dissociation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus neutralization from antibodies specific to major envelope protein surface epitopes. Virology. 2012;433:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Li H., Liu Y., Pan Y., Deng F., Song Y., Tang X., He Q. New variants of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, China, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18(8):1350–1353. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.120002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.Q., Ge J.W., Qiao X.Y., Jiang Y.P., Liu S.M., Li Y.J. High-level mucosal and systemic immune responses induced by oral administration with Lactobacillus-expressed porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) S1 region combined with Lactobacillus-expressed N protein. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;93(6):2437–2446. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3734-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson D.M., Magstadt D.R., Arruda P.H., Hoang H., Sun D., Bower L.P., Bhandari M., Burrough E.R., Gauger P.C., Pillatzki A.E., Stevenson G.W., Wilberts B.L., Brodie J., Harmon K.M., Wang C., Main R.G., Zhang J., Yoon K.J. Pathogenesis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus isolate (US/Iowa/18984/2013) in 3-week-old weaned pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;174(1–2):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan W.A., Hauler F., Williams C.R., Bidgood S.R., Mallery D.L., Crowther R.A., James L.C. Regulation of virus neutralization and the persistent fraction by TRIM21. J. Virol. 2012;86(16):8482–8491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00728-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H.W., Norman J.O., Lambert G. Age dependent resistance to transmissible gastroenteritis of swine (TGE). I. Clinical signs and some mucosal dimensions in small intestine. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1973;37(2):157–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y., Igarashi T., Haigwood N., Sadjadpour R., Plishka R.J., Buckler-White A., Shibata R., Martin M.A. Determination of a statistically valid neutralization titer in plasma that confers protection against simian-human immunodeficiency virus challenge following passive transfer of high-titered neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2002;76(5):2123–2130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2123-2130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman J.O., Lambert G., Moon H.W., Stark S.L. Age dependent resistance to transmissible gastroenteritis of swine (TGE). II. Coronavirus titer in tissues of pigs after exposure. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1973;37(2):167–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Lee K.W., Choi H.W., Lee C. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of recombinant S1 domain of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein. Arch. Virol. 2014;159(11):2977–2987. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang K., Shyu D.L., Dhakal S., Hiremath J., Binjawadagi B., Lakshmanappa Y.S., Guo R., Ransburgh R., Bondra K.M., Gauger P., Zhang J., Specht T., Gilbertie A., Minton W., Fang Y., Renukaradhya G.J. Evaluation of humoral immune status in porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) infected sows under field conditions. Vet. Res. 2015;46(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0285-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.J., Song D.S., Park B.K. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) field isolates in Korea. Arch. Virol. 2013;158(7):1533–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1651-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudel S., Park J.E., Jang H., Hyun B.H., Yang D.G., Shin H.J. Evaluation of antibody response of killed and live vaccines against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in a field study. Vet. Q. 2014;34(4):194–200. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2014.973999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pensaert M.B., de Bouck P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch. Virol. 1978;58(3):243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijpers A., van Nieuwstadt A.P., Terpstra C., Verheijden J.H. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus as a cause of persistent diarrhoea in a herd of breeding and finishing pigs. Vet. Rec. 1993;132(6):129–131. doi: 10.1136/vr.132.6.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puvanendiran S., Stone S., Yu W., Johnson C.R., Abrahante J., Jimenez L.G., Griggs T., Haley C., Wagner B., Murtaugh M.P. Absence of porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1) and high prevalence of PCV 2 exposure and infection in swine finisher herds. Virus Res. 2011;157(1):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverberi R., Reverberi L. Factors affecting the antigen-antibody reaction. Blood Transfus. 2007;5(4):227–240. doi: 10.2450/2007.0047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.R., Figueiredo M.C., Abrahante J.E., Murtaugh M.P. Immune response to ORF5a protein immunization is not protective against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;164(3–4):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig J.T., Hombach J., Barrett A.D. Guidelines for plaque-reduction neutralization testing of human antibodies to dengue viruses. Viral Immunol. 2008;21(2):123–132. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif L.J. Coronavirus immunogens. Vet. Microbiol. 1993;37(3–4):285–297. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90030-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E.J., Smith R.J. Identifying the conditions under which antibodies protect against infection by equine infectious anemia virus. Vaccines (Basel) 2014;2(2):397–421. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2020397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingai M., Donau O.K., Plishka R.J., Buckler-White A., Mascola J.R., Nabel G.J., Nason M.C., Montefiori D., Moldt B., Poignard P., Diskin R., Bjorkman P.J., Eckhaus M.A., Klein F., Mouquet H., Cetrulo Lorenzi J.C., Gazumyan A., Burton D.R., Nussenzweig M.C., Martin M.A., Nishimura Y. Passive transfer of modest titers of potent and broadly neutralizing anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies block SHIV infection in macaques. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211(10):2061–2074. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D., Park B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes. 2012;44(2):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D.S., Oh J.S., Kang B.K., Yang J.S., Moon H.J., Yoo H.S., Jang Y.S., Park B.K. Oral efficacy of Vero cell attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus DR13 strain. Res. Vet. Sci. 2007;82(1):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson G.W., Hoang H., Schwartz K.J., Burrough E.R., Sun D., Madson D., Cooper V.L., Pillatzki A., Gauger P., Schmitt B.J., Koster L.G., Killian M.L., Yoon K.J. Emergence of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in the United States: clinical signs, lesions, and viral genomic sequences. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2013;25(5):649–654. doi: 10.1177/1040638713501675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Feng L., Shi H., Chen J., Cui X., Chen H., Liu S., Tong Y., Wang Y., Tong G. Identification of two novel B cell epitopes on porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;131(1–2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K.K., Zhang A.J., Hung I.F., Xu T., Ip W.C., Wong R.T., Ng J.C., Chan J.F., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. High titer and avidity of nonneutralizing antibodies against influenza vaccine antigen are associated with severe influenza. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(7):1012–1018. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00081-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell D.A. Neutralization of viruses by homologous immune serum. II. Theoretical study of the equilibrium state. J. Exp. Med. 1953;97(6):863–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.97.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova A.N., Marthaler D., Wang Q., Culhane M.R., Rossow K.D., Rovira A., Collins J., Saif L.J. Distinct characteristics and complex evolution of PEDV strains, North America, May 2013-February 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20(10) doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley R.D., Lager K.M. Increased litter survival rates, reduced clinical illness and better lactogenic immunity against TGEV in gilts that were primed as neonates with porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV) Vet. Microbiol. 2003;95(3):175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey R., Nason M.C., Nishimura Y., Follmann D.A., Martin M.A. Neutralizing antibody titers conferring protection to macaques from a simian/human immunodeficiency virus challenge using the TZM-bl assay. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2010;26(1):89–98. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E.N. An apparently new syndrome of porcine epidemic diarrhoea. Vet. Rec. 1977;100(12):243–244. doi: 10.1136/vr.100.12.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Huo J.Y., Chen L., Zheng F.M., Chang H.T., Zhao J., Wang X.W., Wang C.Q. Genetic variation analysis of reemerging porcine epidemic diarrhea virus prevailing in central China from 2010 to 2011. Virus Genes. 2013;46(2):337–344. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0867-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Chen J., Shi H., Chen X., Shi D., Feng L., Yang B. Identification of a conserved linear B-cell epitope in the M protein of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Virol. J. 2012;9:225. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]