Graphical abstract

Keywords: SARS-CoV, Helicase, Aryl diketoacid (ADK), Duplex DNA-unwinding activity

Abstract

As anti-HCV aryl diketoacids (ADK) are good metal chelators, we anticipated that ADKs might serve as potential inhibitors of SARS CoV (SCV) NTPase/helicase (Hel) by mimicking the binding modes of the bismuth complexes which effectively competes for the Zn2+ ion binding sites in SCV Hel thereby disrupting and inhibiting both the NTPase and helicase activities. Phosphate release assay and FRET-based assay of the ADK analogues showed that the ADKs selectively inhibit the duplex DNA-unwinding activity without significant impact on the helicase ATPase activity. Also, antiviral activities of the ADKs were shown dependent upon the substituent. Taken together, these results suggest that there might be ADK-specific binding site in the SCV Hel, which warrants further investigations with diverse ADKs to provide valuable insights into rational design of specific SCV Hel inhibitors.

Viral helicases couple energy from nucleotide triphosphate (NTP) hydrolysis with the unwinding of duplex viral nucleic acid, and drugs targeting viral helicases are currently being tested for the treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV)1 and hepatitis C virus (HCV)2 infections. Previous studies on SCV life cycle demonstrated that the SCV NTPase/helicase (SCV Hel) is also likely to be an attractive target for anti-SCV therapy.3, 4, 5 A 100-residue cysteine-rich metal binding domain (MBD) is located at the N terminus of the SCV Hel and it is known that binding of the Zn2+ ion to the SCV Hel MBD is essential for enzymatic activity and viral viability.6 Recently, Yang et al. reported that bismuth complexes effectively competes for the Zn2+ ion binding sites thereby disrupting and inhibiting both the NTPase and helicase activities.7, 8

Aryl diketoacids (ADK) are known to inhibit several viral target enzymes such as HIV-1 integrase9 and HCV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)10, 11 by sequestration of the active site metal. Previously, we have also shown potent inhibition of HCV RdRp (IC50 = 0.96–30 μM) by several novel ADK analogues (1–8, Fig. 1 ).12

Figure 1.

ADK analogues investigated in this study.

Thus, it was of our interest to test if our novel ADK analogues could serve as potential inhibitors of SCV Hel by mimicking the binding modes of the bismuth complexes to the MBD.

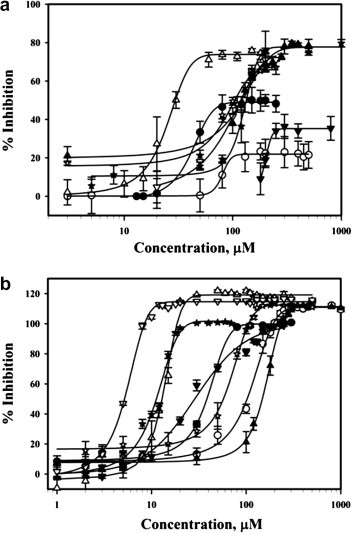

Syntheses12 of the ADKs as well as cloning and purification of the SCV Hel7 were performed as previously described. The inhibition of ADKs against SCV Hel ATPase activity was measured by a phosphate release assay: phosphate release during ATP hydrolysis by SCV Hel was measured by colorimetric method based on complex formation with malachite green and molybdate (AM/MG reagent).13, 14 Briefly, a 25 μl solution of SCV helicase (400 nM) in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.6) buffer was added to each well of the 96-well assay plate which already contained 0.5 μl of various concentrations of chemical compounds.15 After incubation for 5 min at rt, reactions were started by adding 25 μl of reaction solution [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.6), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 4 nM circular ssDNA M13] to each well and then further incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped by adding 200 μl of AM/MG reagent (0.034% malachite green, 1.05% ammonium molybdate, 0.04% Tween 20, in 1 M HCl) and the color was developed for 5 min at rt. Absorbance at 620 nm was measured and the amount of phosphate released was quantitated using inorganic phosphate standard curve. Each experiment was repeated three times and averaged. As shown in Figure 2 a and Table 1 , no ADK investigated in this study showed significant inhibition activity against the enzyme. Among them, only 1 and 4 exhibited moderate inhibition activities against helicase ATPase with IC50 values of 41.3 and 24.4 μM, respectively.

Figure 2.

% Inhibition of SCV Hel by ADKs (1: ●, 2: ○, 3: ▴, 4: Δ, 5: ☆, 6: ▾, 7: ▽, 8: ★): (a) ATPase activity, (b) duplex DNA-unwinding activity.

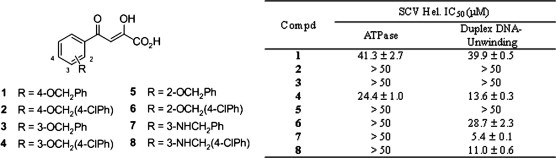

Table 1.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ATPase | Duplex DNA-unwinding | |

| 1 | 41.3 ± 2.7 | 39.9 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | >50 | >50 |

| 3 | >50 | >50 |

| 4 | 24.4 ± 1.0 | 13.6 ± 0.3 |

| 5 | >50 | >50 |

| 6 | >50 | 28.7 ± 2.3 |

| 7 | >50 | 5.4 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | >50 | 11.0 ± 0.6 |

The inhibition of ADK analogues against the SCV Hel duplex DNA-unwinding activity was measured by FRET-based assay as previously described16, 17 and the results are summarized in Figure 2b and Table 1. Similar to the helicase ATPase assay, neither 2 nor 3 showed inhibition of helicase duplex DNA-unwinding activity even at a concentration of 100 μM, and the inhibitory activities of 1 and 6 were only marginal (39.9 and 28.7 μM, respectively). However, three ADK analogues showed modest to potent inhibition of SCV Hel duplex DNA-unwinding activity with IC50 values of 13.6 (4), 5.4 (7), and 11.0 μM (8), which are comparable to those of the previously reported inhibitors including bismuth complexes (3.0–11.0 μM),8 HE602 (6.0 μM),18 and vanillinbananin (2.7 μM).3 It is worth to note that, unlike bismuth complexes which showed the same order of inhibition in both ATPase and duplex DNA-unwinding assay,8 the ADK analogues showed selective inhibition against the duplex DNA-unwinding activity. Thus, it is conceivable that the ADKs might have mechanism of inhibition different from that of the bismuth complexes. Also noteworthy is that the ADK analogues are the only SCV Hel inhibitors reported to date with structure–activity relationships: the regiochemistry as well as the aromatic substituent dramatically influence the anti-SCV activities of the ADKs. In particular, compounds with para-relationship between the diketoacid moiety and the OCH2Ar group (1 and 2) do not show antiviral activities. Also, the chlorine substituent on the terminal aromatic ring has completely different effects on the inhibitory activities of the ADKs. In comparison with 7, the inhibitory activity against the target enzyme of 8 is rarely affected by chlorination. On the contrary, chlorine substitution resulted in significant changes in antiviral activities of 4 and 6 in comparison with their unsubstituted counterparts 3 and 5. Taken together, this result suggests a possible specific binding site for the ADKs in the SCV Hel, which warrants further investigation of more structurally diverse ADK analogues on their anti-SCV activities to provide definitive structure–activity relationships as well as the possible binding site.

In summary, anti-HCV ADK analogues showed potent and selective inhibition against the SCV helicase duplex DNA-unwinding activity but not against the helicase ATPase activity. Anti-SCV activities of the ADKs were shown dependent upon the regiochemistry as well as the substituent of the ADKs. Further investigations will be required with diverse ADKs to delineate definitive structure–activity relationships as well as the ADK-specific binding site, which will provide valuable insights into rational design of specific SCV Hel inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported a grant from Biogreen 21 Program, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and a grant from Agenda 11-30-68 (NIAS). C.L. is supported by the second Brain Korea 21. Y.-J. Jeong was supported by the Korean Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund) (KRF-2007-313-C00451), Seoul R&BD Program (10580) and the research program 2008 of Kookmin University in Korea.

Contributor Information

Yong-Joo Jeong, Email: jeongyj@kookmin.ac.kr.

Youhoon Chong, Email: chongy@konkuk.ac.kr.

References and notes

- 1.Crute J.J., Grygon C.A., Hargrave K.D., Simoneau B., Faucher A.M., Bolger G., Kibler P., Liuzzi M., Cordingley M.G. Nat. Med. 2002;8:386. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowski P., Schalinski S., Schmitz H. Antiviral Res. 2002;55:397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanner J.A., Zheng B.-J., Zhou J., Watt R.M., Jiang J.-Q., Wong K.-L., Lin Y.-P., Lu L.-Y., He M.-L., Kung H.-F., Kesel A.J., Huang J.-D. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:303. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernini A., Spiga O., Venditti V., Prischi F., Bracci L., Huang J.D., Tanner J.A., Niccolai N. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;343:1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Chai Y.B., Lu L.Y., Lin M.C., Peiris J.S., Poon L.L., Kung H.F., Huang J.D. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300328200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seybert A., Posthuma C.C., van Dinten L.C., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E., Ziebuhr J. J. Virol. 2005;79:696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.696-704.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang N., Tanner J.A., Wang Z., Huang J.-D., Zheng B.-J., Zhu N., Zun H. Chem. Commun. 2007:4413. doi: 10.1039/b709515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang N., Tanner J.A., Zheng B.J., Watt R.M., He M.L., Lu L.Y., Jiang J.Q., Shum K.T., Lin Y.P., Wong K.L., Lin M.C.M., Kung H.F., Sun H., Huang J.-D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:6464. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazuda D., Felock P., Witmer M., Wolfe A., Stillmock K., Grobler J.A., Espeseth A., Gabryelski L., Schleif W., Blau C., Miller M.D. Science. 2000;287:646. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summa V., Petrocchi A., Pace P., Matassa V.G., De Francesco R., Altamura S., Tomei L., Koch U., Neuner P. J. Med. Chem. 2004;7:14. doi: 10.1021/jm0342109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Santo R., Fermeglia M., Ferrone M., Paneni M.S., Costi R., Artico M., Roux A., Gabriele M., Tardif K.D., Siddiqui A., Pricl S. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6304. doi: 10.1021/jm0504454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J., Kim K.-S., Lee H.S., Park K.-S., Park S.Y., Kang S.-Y., Lee S.J., Park H.S., Kim D.-E., Chong Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:4661. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baykov A.A., Evtushenko O.A., Avaeva S.M. Anal. Biochem. 1988;171:266. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardell A.D., Errington W., Ciaramella G., Merson J., McGarvey M.J. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin G.R., Yvette M.N., Chrisotomos P., Laurence H.P., Paul W., Wynne A. Anal. Biochem. 2004;327:176. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang K.J., Lee N.R., Yeo W.S., Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;366:738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briefly, carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-modified 45-base-oligomer and fluorescein-modified 25-base-oligomer were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies: 5′-20T25Tam (5′-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGAGCGGATTACTATACTACATTAGA(TAMRA)-3′) and 3′-0T25Flu (5′-(Fluorescein)TCTAATGTAGTATAGTAATCCGCTC-3′). The helicase substrate was prepared by annealing the two oligomers, which resulted in 25 base pairs of dsDNA with single-stranded 20 dT of 5′-overhang. A 80 μl solution of SCV helicase (150 nM) in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) buffer was added to each well of the 96-well assay plate which already contained 1 μl of various concentrations of chemical compounds. After 5 min incubation at rt, the FRET based dsDNA unwinding assay was started by addition of 20 μl 5X reaction solution [5 mM MgCl2, 45 mM ATP, 25 mM DTT, and 100 nM dsDNA substrate in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)]. The reaction mixture was further incubated for 2 min at 37 °C and stopped with 100 μl of termination solution [0.1 M EDTA and 0.4 μM trap DNA (unmodified 25 bases 3′-0T25 oligomer) in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)]. The sample was excited at 485 nm and the fluorescence was measured at 535 nm.

- 18.Kao R.Y., Tsui W.H.W., Lee T.S.W., Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Huang J.-D., Hu L., Chen G., Chen Z., Zhang L., He T., Chan K.-H., Tse H., To A.P.C., Ng L.W.Y., Wong B.C.W., Tsoi H.-W., Yang D., Ho D.D., Yuen K.-Y. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1293. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]