Abstract

This study examines the factors that lay behind the development of the Golden Week holiday system in China in 1999 and 2007. It does so by evaluating three dimensions, namely (a) dominant government policy, (b) the pattern of tourism demand and (c) the degree of public participation in the policy making process. Both quantitative and qualitative methodologies are used in a content analysis of 45 related documents. The results indicate that while little relationship existed between the demands of tourism and public policy in both 1999 and 2007, the requirements of social policies and a greater role being attributed to public participation in the policy making were more emphasized in 2007. The theoretical contributions and practical implications of this study are also addressed.

Keywords: Policy making, Policy change, Policy demands, Tourism policy, Golden week holiday

1. Introduction

When it comes to the underpinning forces driving modern tourism developments, increased leisure time has long been regarded as a factor that is no less significant than others including soaring disposable income and faster air-borne transportations (Fayos-Sola and Bueno, 2001, Wahab and Pigram, 1997). In China, the greater availability of leisure time in the recent decade has been directly attributed to the country's exponential tourism growth during the same period, especially its domestic tourism flows, which reached over 1.6 billion person times in 2007 (Gao, 2006, Shao, 2008). When a ‘blowout’ in tourism demand was witnessed in October 1999, China's central government authorities responded by pushing through a revision of the Regulation on National Festival and Memorial Day Public Holidays that took effect from May 2000. In addition to adding the total number of annual public holidays, in conjunction with executive orders made by the government authorities, the revised regulation facilitated the establishment of three week-long holidays each year by transferring weekend days off from adjacent weekends into the week of public holidays.

These three weeks have officially been labeled somewhat grandly as ‘golden week’, indicating the golden opportunities looming ahead for the country's tertiary and service industries, with the tourism sector no exception here. By 2007, the three golden week had already accounted for 1/3 and 40% respectively of annual tourist volumes and tourism receipts in the Chinese domestic tourism market (The China National Tourism Administration (CNTA), 2008). Especially, the vital importance of the golden week was fully appreciated in 2003 when the October golden week completely made up for the considerable losses suffered by tourism businesses during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic which plagued China in the first half of that year (Gao, 2004). At the same time, the golden week holiday have also become important occasions for Chinese people to engage in outbound tourism activities, thereby expanding the influences of the golden week to the world tourism arena (ACNielsen, 2007).

However, in December 2007, amid a fierce debate that aroused the attention of all elements of Chinese society, the 1999 regulation was revised again, canceling two days of the May Day vacation and adding three new holidays on traditional Chinese festivals from 2008 onwards, thereby increasing the total number of annual public holidays to 11. Furthermore, the 2007 revision formally institutionalized the practice of commuting days from adjacent weekends to form week-long holidays. The Ordinance on Paid Vacations for Employees was issued at the same time, entitling employees of all types of organizations in China to annual paid vacations. The detailed differences between the two policies embodied in these two pieces of legislation are listed in the Appendix.

Recognizing the significance of the ‘golden week’ system to the development of the Chinese tourism industry as a whole, this paper fundamentally aims to comparatively profile and analyze the respective policy making mechanisms that operated in 1999 and 2007 in relation to the golden week holiday. We focus in particular on a systematic exploration of the political and bureaucratic forces that underpinned the policy changes made in 1999 and 2007. The rationales behind such an exploration are consolidated by both the structural and operational uniqueness of public policy systems in China, and current research paucity in the golden week holiday at large. The specific objectives of the paper include: identifying the major policy demands; investigating the trajectory of bureaucratic competition; and examining the respective policy agenda setting regimes in the formulations of the regulations of the 1999 and 2007 golden week holiday.

2. Literature review

2.1. The central status of policy making in public policy analysis

Public policy is defined as the series of normative principles stipulated by the government with regard to the action or development of social phenomena over a certain period of time (Liu, 2006). Policy analysis should center around the temporal nature of the whole policy process (Davis et al., 1993). The paramount status of policy making in the whole policy process has also been recognized (Hall & Jenkins, 1995). Indeed, those who insist that the policy process is a non-divisible whole often synonymize policy making with the policy process itself (Simon, 1997). Policy making can be generally be considered as a continuous course of action taken over time that involves many decisions (Anderson, 1976). Graddy and Ye (2008) divided the policy making mechanism into two temporally ordered stages: first, the triggering events prompting policy making, and second, the contextual components of policy making. With regard to the contextual components of policy making, a wide range of tangible and intangible factors are identified, such as the bureaucratic organizations concerned, which may include legitimate decision-making bodies and influencing institutions, political and bureaucratic leaders, interest groups, the general community, and the characteristics of policy making legacies.

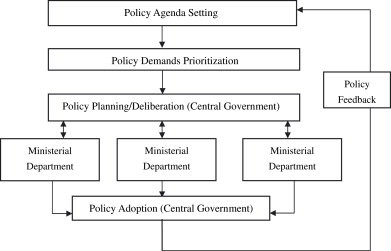

Specifically, the policy making mechanism can be accounted for by the policy making process, in the course of which the influences of diverse political and bureaucratic components on policy making can be duly factored in (Geva-May, 2004, Li, 2006). Such a policy making process can be further disaggregated into the following temporally ordered stages: policy issue identification, policy agenda setting, policy demand prioritization, policy decision planning, and policy output legitimization. This process can be a cyclical integrity that takes into account the ongoing changes to a particular policy over a certain period of time (Hill, 1993). The Golden Week Holiday System discussed in this paper is just a case in point illustrating such a cyclical process.

The first stage of policy issue identification concerns the confirmation of the specific policy issue in its entirety, as evaluated by such features as identification of the issue boundary, exploration of factual proof, enumeration of objectives, identification of the scope of policy, demonstration of potential costs and benefits, and lastly the review of the presentation of the issue (Li, 2006). In the second stage of policy agenda setting, policy agenda is defined as the series of policy issues selected by decision makers or regarded by them as pending actions (Cobb & Elder, 1972). Policy agenda setting necessitates a platform upon which different and often contesting policy demands are presented, deliberated and, finally, prioritized. The later stages of policy planning, adoption and legitimization, in terms of the policy contents determined, retrospectively reflect in either explicit or implicit manners the details of the process of demand prioritization aforementioned. Therefore, given their pivotal roles in deciding what and how the policies are made or changed, the stages of policy agenda setting and policy demand prioritization naturally call for focused attention in public policy research.

In addition, out of the stages outlined above, it is during the second phase of agenda setting that external influences to the bureaucratic establishments are factored in, to whatever extent. A policy agenda can also be understood as a channel through which policy issues are incorporated into the institutionalized decision-making agenda of the government (Zhang, 1992). Cobb and Elder (1972) identified two types of policy agenda: systematic agendas and government agendas. Systematic agendas are mainly composed of policy issues the general public believes to be pending actions, together with those that have been institutionalized and brought under the government's jurisdiction. Systematic agendas are set at a preliminary stage in the sense that policy issues are generally vaguely framed and sketchy in content or scope, and measures for or solutions to such issues are not necessarily available at this stage. However, government agendas are set at the official stage in which policy issues are heeded by the government through its relevant bureaucratic organizations, sometimes with measures or solutions already drafted.

Prior research highlights the fact that not all issues on the systematic agenda can be placed on the government agenda, and more often than not, issues on the systematic agenda are prevented from being included on the government agenda (Jones, 1977). Hence, the regime epitomizing the interactions between the government and the public directly influences whether and how systematic agendas are transformed into government agendas (Webler, 1995). In other words, such a regime indicates the extent of citizen participation during the deliberative process of policy making, which is expected to fulfill such characteristics as procedural fairness and competency in contemporary western democratic societies (Renn, Webler & Wiedemann, 1995). From the government perspective, Jordan and Richardson (1982) proposed five categories of such a regime, namely sectorization, consultation, exchange, institutionalization of compromise, and clientelism, in descending order of the degree of citizen participation. Sectorization refers to unilateral government demarcation of the general public into isolated sectors for which sector-specific policies are required, while clientelism indicates the paradigm shift in the ideologies underlying institutional arrangements in which government is reduced to a business entity that is little different from any business in the corporate world, both in terms of the interactions between the government and the public and the management of government operations themselves. The remaining three categories of consultation, exchange, and institutionalization are located on a spectrum flanked by the two categories described above.

2.2. Vacation policies

Although there is a substantial degree of diversity in the vacation policies in place in different countries around the world, they generally share a common path of historical development, as vacation policies are a natural product of both the economic prosperity brought about by the first industrial revolution and the political enhancement of the recognition of the state since the late 1700s (Schor, 1991). The International Labor Organization (ILO) (in Richards (1999)) has divided vacation policies into three major categories: regulations on public holidays, regulations on weekly working hours, and regulations on paid holidays.

The first branch of vacation policy, regulations on public holidays, is believed to be politically uncontroversial and stable, fully reflecting the current political system of the country in terms of political power arrangements and the imposition of dominant political ideology (Perry, 2004). Such political influences are often epitomized in the integration of the cultural traditions of certain ethnic groups of a country into its public holidays. Derocco, Dundas and Zimmeman (1996) identified three types of public holidays: political holidays, religious holidays, and secular holidays. While regulations on such public holidays have fallen exclusively within the domain of the state, the second and third branches of vacation policy, regulations on weekly working hours and those on paid holidays, have resulted from struggles for social rights fought between a variety of social groups, most significantly workers, as represented by unions, and business owners (Richards, 1999).

Esping-Anderson (1990) categorizes modern day Western societies that feature weekly working hours and paid holiday arrangements as part of the social welfare system into three types: liberal welfare states, corporatist welfare states, and social democratic states. Liberal welfare states such as the USA, Canada, Australia, and Japan, seldom intervene in social welfare arrangements between employers and workers, and given the low level of unionism in such countries, employers often take advantage in bargaining over employment conditions. Corporatist welfare states encompass most Western European countries, where collective bargaining and state intervention are closely related to the extent that there is a pattern of the former raising demands beyond statutory minima followed by fresh legislation ensuring universal coverage (Green & Potepan, 1988). While Great Britain is an exception here with no legislation on minimum standards, unions have been strong advocates for leisure time arrangements (Gao, 2007). Social democratic states, including Scandinavian countries and The Netherlands, are most tilted toward institutionalized government involvement in vacation policies, with periodic legislative formalization observed. At the same time, the activeness of government in welfare regulations in such societies is also believed to be strongly influenced by the ideologies of the ruling political party (Samuel, 1993). For instance, comprehensive labor welfare regulations were witnessed in France during the sporadic periods in which the government was controlled by socialist parties from the 1930s to the 1970s. The first French regulations on paid annual holidays were implemented in 1936 when a five-day working week regime was introduced. International organizations, with the ILO in particular taking center stage, have also had a significant influence on vacation polices, although some of their provisions are not binding on member states (Gao, 2006). The governments of socialist countries in Eastern Europe, as the embodiment of a political ruling class of the proletariat, have played a proactive role in formulating vacation policies (Hall, 1994).

Meanwhile, in light of the general trend toward a globalized world, recent decades have seen international organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) release a number of documents with substantial sections on leisure time (O'Rourke, 2003, Wick, 2001). All these documents have emphasized the legitimate right of individuals to a reasonable amount of leisure time and the importance of such leisure time to the promotion of tourism development. Although leisure time provisions included in such documents are not binding on signatory nations, they have served as valuable reference points for the countries concerned in formulating leisure time-related regulations.

2.3. Current research on the golden week holiday system

The overwhelming majority of current research on the golden week holiday system is focused on areas such as the macro-level cost/benefit analysis of the economic impact of the system, service, security, and complaints problems encountered during golden week holiday at the micro level, and regulatory enhancements made by related government departments during such holidays (Chen and Li, 2007, Ren, 2007, Sheng, 2005, Yang, 2005, Yang, 2006). However, little research has examined the driving force behind this system—the Chinese government. China has endeavored to establish a socialist market economy over the past three decades, and the Chinese government, with a uniquely centralized party-state dualism, a largely internally driven policy making model, and a highly centralized bureaucracy, is still believed to exercise firm control over the trajectory of the majority of social and economic phenomena in the country (Chao & Dickson, 2001; Zhang et al., 2005). The golden week holiday are no exception. The Chinese government's move to commute days from adjacent weekends and form week-long holidays is an example of the considerable executive leverage it has. This type of executive power has only been seen sporadically in countries such as France, Brazil, and Japan several decades ago (Samuel, 1993). In addition, policy making in the golden week holiday has been unique because of the relative instability of the policy subsystem of the golden week holiday, with dynamic shifts in the structure and interactions of the components both outside and within the Chinese bureaucracy. Actually, as the paper is being written, hot debates are being conducted over further policy changes to the golden week holiday system. Therefore, any academic investigation into the golden week phenomenon, involving as it does the synchronized activities of over one billion people, must include an examination of the roles of relevant government bodies and their policies. Given the relative paucity of prior studies in this area, this paper aims to fill this research void through a comparative identification and evaluation of the key dimensions of the policy making mechanisms for the golden week holiday system in 1999 and 2007, respectively.

3. Method

Based on the analysis undertaken in the literature review, a conceptual overview of the research components is proposed in Fig. 1 . Fig. 1 shows that the bureaucratic organization empowered to make policy on the golden week holiday system is the State Council of China, China's equivalent to a central government cabinet. The China National Tourism Administration (CNTA) is one of the stakeholder bureaucratic departments involved in the policy making process and represents tourism-related interests. The other departments involved in this process, which are not listed in Fig. 1 due to the research objectives of this study, include a variety of agencies such as the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Transportation, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, the Ministry of Public Security, and the State Administration of Work Safety.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual overview of the research components.

This paper is an explanatory study with a primary research objective of describing the respective policy making mechanisms the State Council used for the golden week holiday system in 1999 and 2007. The main research question for this study is as follows: how were the 1999 and 2007 golden week holiday system policies made? Corresponding to the afore-reviewed literature on the pivotal stages of policy agenda setting and policy demand prioritization in the policy making process, the primary research objective can be further divided into the following three specific objectives: (1) to investigate the respective policy inputs in terms of the major policy demands of the two policies; (2) to explore the extent of bureaucratic competition in terms of the weight of tourism-related policy demands when each of the two policies were formulated; and (3) to examine the respective policy agenda setting regimes in terms of the level of civil participation in formulating the two policies.

These three specific dimensions of the policy making mechanism focus on the decision-making context of the policy making mechanism, and are selected for evaluation here in recognition of rationales conforming to both the general literature on public policy making mechanisms and the peculiarities of tourism policies, together with the unique Chinese political and bureaucratic contexts. The first research objective on the major respective major policy demands in the two years in question is a key dimension of the policy making process, which serves as the foundation upon which precise policy is formulated (Li, 2006). The second research objective addresses the ‘noisy’ tourism policy arena in which, due to the complexity of the tourism industry, there are a number of diverse competing interests (Jeffries, 2001). Finally, to assess the nature of policy agenda setting for what is a social phenomenon in contemporary China in a social context that is currently in the ‘primary stage of socialism’ and undergoing a fundamental transformation into a socialist market economy, the third research objective is intended to explore either consistency with or deviation from existing theoretical elaborations, most of which characterize Chinese public policy agenda setting in general as largely internally driven because of a distinct party-state dualism and a highly centralized bureaucracy (Wu, 2005).

Taking account of the peculiarities of public policy studies in both the tourism and Chinese contexts, this study undertakes a content analysis of documents related to policy making on the golden week holiday system for the period 1999–2007 with the assistance of computer analysis software including SPSS and QSR NUDIST (Qualitative Solutions and Research, Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing). Content analysis refers to the systematic analysis of textual data already coded for pattern and structure examination and confirmation, category development, and aggregation into perceptible constructs (Gray and Densten, 1998, Insch and Moore, 1997). One of the unique benefits of content analysis is its compatibility with both qualitative and quantitative methods, in that it is capable of capturing a richer sense of the concepts expressed within the data due to its qualitative basis, and, at the same time, classifying words into content categories on a quantitative basis, which is why content analysis is also described as a form of contingency analysis in which content categories are extracted and the number of times a theme appears in the text counted (Roberts, 2000, Weber, 1985). Content analysis has been intensively applied in public policy research, and its merits in the tourism realm have been gradually appreciated in recent years, which is partly attributed to the proliferation of internet-based contents as research data sources (Hall & Valentin, 2005). By far, The tourism discipline has witnessed the successful and convincing utilizations of content analysis in such fields as the effects of tourism advertising materials and campaigns (Henderson, 2003), image building of tourism destinations (Sirakaya and Soenmez, 2000, Zhang and Cameron, 2003), variations in conceptual understandings in tourism (Cloke and Perkins, 2002, Garrod, 2003), and the perceptions of tourism from the perspectives of the tourists (Chen et al., 2001, Yagi, 2001).

The research process undertaken for this study was as follows. First, documents and other materials in multi-media forms including written, audio and visual formats were collected in an effort to gather a critical volume of documentary evidence on golden week policies. A total of forty-five documents were gathered, including minutes of relevant official conferences and meetings, speeches made by leading officials of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council, and reports from various types of mass media such as television, newspapers, and magazines. Other than six documents that were entirely devoted to discussions on golden week holiday policy making in either 1999 or 2007, the remaining 39 all referred to both years. The contents of the documents were then analyzed utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods, with the assistance of SPSS and QSR NUDIST software.

The analysis was conducted in two steps. First, from a qualitative perspective, two separate files were created in NUDIST to correspond to the respective time slots of 1999 and 2007, and the relevant data were input accordingly. The units of analysis for this study were text units that correspond to the respective research objectives. Such text units can be words, phrases, or short sentences of no longer than 30 words, and we were able to make minor grammatical changes if necessary without distorting the original meaning. During the analysis, each of the three specific research objectives was coded as a primary construct for each file created. Text units from the documents that the authors deemed relevant to a specific primary construct were coded and categorized under the primary construct. Similar text units were aggregated after coding. Meanwhile, text units which were overlapping in that they referred to two or more research objectives were accounted for separately under the related primary construct. With regard to all three of the research objectives, coding, re-categorization, and aggregation procedures were conducted to establish the hierarchical structures among related text units under the same primary construct.

To ensure the rigidity and consistency of the coding process, the entire process followed the guidance and requirements set out in Neuendorf's (2002) code book. Specifically, to enhance the internal validity of the data analysis undertaken, we used the cross-coder assessment method during the coding phase of the content analysis. Cross-coder assessment refers to the utilization of more than one coder in coding the same content independently before establishing inter-coder reliability for the adoption of the coded units of analysis (Neuendorf, 2002). Two of the authors of this study first coded the research materials on an independent basis before comparing and assessing the separate codings. Prior evidence (McBeth, Shanahan, Arnell, & Hathaway, 2007) has shown that inter-coder reliability can be established when more than 80% of the codings can be agreed upon. Altogether, the two coders initially agreed on 86%, 82%, and 91% of the codings for each of the three respective research objectives, thereby establishing an acceptable level of inter-coder reliability. For codings in which discrepancies arose, discussions were held until a consensus was reached and all codings were approved. The principles of constant comparative analysis were also observed to reify the inductive approaches adopted in this study to extract new concepts and relationships (Jennings, 2001).

In the second stage of quantitative analysis, corresponding text units from the two files were then input into SPSS to be compared through Chi-square tests and examine their relationships with policy making in the two respective years. In the Chi-square tests, the exact degree of such relationships were represented by calculating indices such as Cramér's V and odds ratios (Veal, 2006). We discuss the findings in the following section.

4. Findings

4.1. Research objective 1: respective policy demands in 1999 and 2007

With regard to the first research objective on the respective policy demands in 1999 and 2007, we identified two categories of policy demands in each year: economic demands and social demands. Both categories can be further divided into different sub-categories as a result of the content analysis. Table 1, Table 2 summarize the respective sub-categories and their measurements in terms of the number of text units. It should be noted that only sub-categories with at least three text units are presented here.

Table 1.

Distributions of economic and social demands of the golden week holiday policy in 1999.

| Economic demands |

Total counts: 78a |

Social demands |

Total counts: 12a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demand category | Count | Demand category | Count |

| (1) Stimulation of domestic consumption | 41 | (1) Celebration of the 50th anniversary of the PRC | 5 |

Development of the real estate industry Development of the real estate industry |

11 | (2) Successful implementation of the five-day working week since 1995 | 3 |

Development of the information industry Development of the information industry |

9 | ||

Development of the automobile industry Development of the automobile industry |

8 | ||

Development of the tourism industry Development of the tourism industry |

6 | ||

Development of the retail industries Development of the retail industries |

3 | ||

| (2) Maintenance of export volume | 20 | ||

maintaining low exchange rate of RMB maintaining low exchange rate of RMB |

7 | ||

continuous impacts of the Asian financial crisis continuous impacts of the Asian financial crisis |

6 | ||

maintaining export of labor-intensive products maintaining export of labor-intensive products |

3 | ||

| (3) recognition of the development level of the Chinese economy | 17 | ||

maintaining cheap labor in China maintaining cheap labor in China |

6 | ||

attracting foreign investment attracting foreign investment |

3 | ||

intetests of mixed-ownership enterprises intetests of mixed-ownership enterprises |

3 |

Sources: developed for this study.

Only demands with at least 3 counts are listed.

Table 2.

Distributions of Economic and Social Demands of the Golden Week Holiday Policy in 2007.

| Economic demands |

Total counts: 64a |

Social demands |

Total counts: 56a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demand category | Count | Demand category | Count |

| (1) Balanced development of various economic sectors | 30 | (1) promoting traditional Chinese culture | 27 |

negative economic effects of tourism during golden week negative economic effects of tourism during golden week |

12 |  enhancing awareness of traditional Chinese festivals enhancing awareness of traditional Chinese festivals |

7 |

balanced development of the finance sector balanced development of the finance sector |

6 |  counteracting rivalry ‘patenting’ for Chinese cultural by other countries counteracting rivalry ‘patenting’ for Chinese cultural by other countries |

5 |

positive economic effects of tourism during golden week positive economic effects of tourism during golden week |

5 |  relative cultural values of different Chinese festivals relative cultural values of different Chinese festivals |

5 |

balanced development of the retail industries balanced development of the retail industries |

3 |  improving identification with the Chinese authorities by overseas Chinese improving identification with the Chinese authorities by overseas Chinese |

4 |

balanced development of the transportation industries balanced development of the transportation industries |

3 |  improving identification with the Chinese authorities by Chinese Nationals improving identification with the Chinese authorities by Chinese Nationals |

3 |

| (2) consistency with the development level of the economy | 24 | (3) realizing human rights to leisure time | 17 |

maintaining low labor costs in China maintaining low labor costs in China |

8 |  increasing the total amount of annual public holidays increasing the total amount of annual public holidays |

6 |

maintaining productivity of Chinese labor forces maintaining productivity of Chinese labor forces |

6 |  tackling current lax practice son paid leaves among different sectors tackling current lax practice son paid leaves among different sectors |

4 |

regulating unionized activities regulating unionized activities |

3 |  corresponding to with demands of international organizations corresponding to with demands of international organizations |

3 |

| (4) consideration of macroeconomic conditions | 10 | (2) learning from international practices | 12 |

shifting demographic features of the workforce shifting demographic features of the workforce |

3 |  practices from other Confucius societies on Chinese festival vacations practices from other Confucius societies on Chinese festival vacations |

5 |

flow of immigrant workers flow of immigrant workers |

3 |  practices from other countries on vacation arrangements practices from other countries on vacation arrangements |

3 |

international economic competitions among developing countries international economic competitions among developing countries |

3 |

Sources: developed for this study.

Only demands with at least three counts are listed.

Specifically, the results of the Chi-square test on research objective 1 are listed in Table 3 , which show that there was a significant association between social demands and policy making in 2007 (x 2 [d.f. = 1] = 26.098, p < 0.05). In the policy making process of 2007, social demands accounted for 46.7% of the total number of text units, which compares with the somewhat smaller share of 13.3% recorded in 1999. The odds ratio for social demands in 2007 policy making was 5.69, indicating that social demands were roughly five times more likely to be considered as part of the 2007 policy making process than economic demands. Thus, our conclusion on research objective 1 is that while economic demands were the major considerations in the golden week holiday policy making process undertaken in 1999, the focus had shifted significantly toward social concerns by 2007.

Table 3.

Chi-square results for policy demands of the respective golden week holiday policies in 1999 and 2007.

| 1999 | 2007 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy demands (in text units) | Economic demands | 78 (86.7%) | 64 (53.3%) | 142 |

| Social demands | 12 (13.3%) | 56 (46.7%) | 68 | |

| Total | 90 (100%) | 120 (100%) | 210 | |

| x2 [d.f. = 1] = 13.049, p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.353, Odds ratio for social demands = 5.69 | ||||

Sources: developed for this study.

Table 1, Table 2 also show that the concerns accorded most weight in 1999 were economic in nature, most of which can be categorized into the three related groups of ‘stimulation of domestic consumption’ (41 counts), ‘maintaining export volume in the context of the Asian financial crisis since 1997’ (20 counts), and ‘significant development of the Chinese economy’ (17 counts). In stark contrast, the mere 12 text units on social concerns mostly related to ‘celebration of the 50th anniversary of the founding of The People's Republic of China’ (5 counts) and ‘successful implementation of the five-day working week since 1995’ (3 counts). Therefore, the golden week policy making context in 1999 was predominantly focused on finding solutions to the impact of the Asian financial crisis had had on economic development in China since mid-1997. Admittedly, the specific timing of the introduction of golden week holiday was also related to the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of The People's Republic of China in a demonstration of national identity, but such social demands were overwhelmed by economic imperatives.

When it comes to 2007 policy making, however, the number of social concerns had soared, encompassing such sub-categories as ‘promoting traditional Chinese culture’ (27 counts), ‘realizing human rights to leisure time’ (17 counts), and ‘learning from international practices’ (12 counts). For instance, the designation of the Qingming, Duanwu, and Mid-autumn festivals as national holidays were attributed to the considerable importance of these three festivals in traditional Chinese culture and their greater material reification in comparison with other proposed holidays such as the Yuanxiao and Chongyang festivals. In addition, current practice in both developed and developing countries and the Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan territories were also referenced in 2007 policy making.

However, it should also be pointed out that although the 2007 policy making process involved a greater focus on social concerns than in 1999, economic concerns still played a dominant role in 2007, which can be best reflected by the decisions made in response to scenarios in which there were conflicting economic and social concerns. For instance, it was noted that the realization of the right to leisure time should not compromise the advantages of cheap labor China enjoyed. In addition, the cancellation of the week-long May Day holiday was motivated by the demand for less disruption of transportation, financial, and stock market activities during holidays.

4.2. Research objective 2: the respective weights attached to tourism demands in 1999 and 2007

Based on the text units gathered for research objective 1, those coded for research objective 2 can be further grouped into two strands: tourism and non-tourism units. The tourism units are underlined in Table 1, Table 2. It is worth noting that text units concerning tourism in both 1999 and 2007 did not overlap with those related to social demands, but fell strictly into the economic demands category. This may illustrate the attitude of the Chinese central authorities, who placed an emphasis on the economic dimensions of tourism.

The results of the Chi-Square test on research objective 2 are provided in Table 4 . The results shown in Table 4 lead to the conclusion that tourism demands were not significantly related to golden week holiday policy making in either 1999 or 2007 (x 2 [d.f. = 1] = 2.966, p = 0.117). In the 2007 policy making process, tourism demands accounted for only 14.2% of the total number of text units. The odds ratio for social demands in the 2007 policy making process was 2.311, indicating that tourism demands were only twice as likely as non-tourism demands to be considered as part of the 2007 policy making process.

Table 4.

Chi-square results for tourism-related policy demands of the respective golden week holiday policies in 1999 and 2007.

| 1999 | 2007 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy demands (in text units) | Tourism demands | 6 (6.7%) | 17 (14.2%) | 23 |

| Non-tourism demands | 84 (93.3%) | 103 (85.8%) | 187 | |

| Total | 90 (100%) | 120 (100%) | 210 | |

| x2 [d.f. = 1] = 2.966, p = 0.117, Cramer's V = 0.119, Odds ratio for tourism demands = 2.311 | ||||

Sources: developed for this study.

For tourism demands taken into account in the 1999 policy making process, the number of counts that that fell into the ‘development of domestic tourism’ category (6 counts) trailed those for three other economic sectors: ‘development of the real estate industry’ (11 counts), ‘development of the information industry’ (9 counts), and ‘development of the automobile industry’ (8 counts), ranking only fourth out of the specific industries promoted by the Chinese authorities in 1999. This ranking indicates that the tourism industry was not singled out as a key field for stimulating domestic consumption in the 1999 policy making process. It can be concluded that policy makers for the golden week holiday system did not pay much heed to the rapid development seen in the domestic and outbound tourism industries since 1999 and their stimulatory effects on other fields such as the retail and transportation sectors.

Although tourism demand nearly doubled from 1999 to 2007, the increase was not significant enough to be strongly associated with 2007 policy making. It should also be noted that of the 17 counts for tourism demand in 2007, over 2/3 (12 counts) were related to the negative economic impact of tourism during the golden week holiday, with the most prominent being statistical evidence that the increase in domestic tourism receipts recorded during the golden week was actually lower than that achieved during normal periods. Hence, the demand for mitigating the negative impact of tourism was directly associated with the abolition of the May Day golden week in 2007, the most radical policy change to the 1999 regulation.

The abolition of the May Day golden week was in stark contrast with the stance of the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA), which, as a department with only deputy-ministerial status within the bureaucracy of the State Council, had firmly stood for the retention of the original 1999 arrangements including three annual week-long holidays during the 2007 policy making process. Furthermore, in terms of bureaucratic leverage on the policy making process, a ministerial department, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), took the initiative throughout the 2007 policy making process.

4.3. Research objective 3: respective regimes for interactions between government and society in 1999 and 2007

A twofold taxonomy was agreed upon for the third research objective, in which we investigated the degree of public engagement in the golden week holiday policy making process in 1999 and 2007. The text units which mention government decision-making were grouped together as ‘from the government’, while those concerning input from general public stakeholders were coded as ‘from the public’. Specifically, the ‘from the government’ category included meetings held within central bureaucratic organizations or participated in by officials from other ministerial departments and provincial authorities. Feedback from official research organizations was also classified as ‘from the government’. Public input was mainly made via public hearings, forums, and discussions in which all elements of Chinese society were invited to participate. In recognition of the peculiarities of the Chinese political system, deliberations at the National People's Congress (NPC), the Chinese national parliament, were deemed to be ‘from the government’, while discussions held at the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), an advisory institution mainly composed of social identities, were deemed to be ‘from the public’.

Table 5 illustrates the correlation between text units on the interaction between government and society in 1999 and 2007. Table 5 shows that input from the public was of moderate significance to the policy making process on golden week holiday in 2007 (x 2 [d.f. = 1] = 4.214, p < 0.05), in which public deliberations accounted for 35% of the total. The odds ratio for ‘from the public’ in the 2007 policy making process was 3.949, indicating that public input was about four times as likely as government input to be considered in the 2007 policy making process.

Table 5.

Chi-square results for government-society interactions of the respective golden week holiday policies in 1999 and 2007.

| 1999 | 2007 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Opinion (in text units) | From the government | 22 (88%) | 26 (65%) | 48 |

| From the public |

|

|

17 | |

| Total | 25 (100%) | 40 (100%) | 65 | |

| x2 [d.f. = 1] = 4.214, p = 0.047, Cramer's V = 0.255, Odds ratio for from society = 3.949 | ||||

Sources: developed for this study.

Specifically, all three counts for ‘from the public’ in the 1999 policy making process were derived from a handful of state-owned enterprises located in Beijing in early 1999. These enterprises were hardly distinguishable from the government at the time, as they were closely attached to relevant ministerial departments and were managed on the basis of a human resource system nearly identical to that of the bureaucracy. The counts for ‘from the government’ in 1999 mainly related to official conferences convened at both the ministerial and central levels.

Of the 14 counts for ‘from the public’ in the 2007 policy making process, however, the earliest recorded count was from a member of the national committee of the CPPCC dating from 2005. The 14 counts included five rounds of forum discussions with different social representatives in three Chinese cities. It is also worth noting that the authorities utilized surveys conducted in 2006 and 2007 to collect views from the public on the potential adjustments to the golden week holiday. Official meetings remained the chief mode of government deliberations in the 2007 policy making process, together with a study on international public holiday practices implemented by an official research institute.

While there are no existing quantitative criteria for evaluating the interaction between the government and the general public against the typology offered in the literature review section of this paper, the authors tentatively define the regime in place in 1999 as ‘sectorization’. This definition is based on government dominance of the policy making process for golden week holiday in 1999, with the government accounting for 88% of the total number of opinion sources. Furthermore, as has been addressed above, the quasi-state nature of the public enterprises which contributed to all of the public submissions made in 1999 also corroborates this definition.

However, the 2007 regime can be defined as one of ‘consultation’ for the three following reasons. First, the 2007 policy making process took place over a longer period in which a series of both institutionalized and non-institutionalized government consultation channels such as the CPPCC, research teams from universities, international experience, and a wider array of representative enterprises, including privately owned firms, played a role. A draft version of the 2007 policy was issued for public comment around twenty days before formal publication of the final policy, although it was later shown that the draft and the final policy were exactly the same. Second, a series of studies based on modern technology such as the Internet and telephone polls were employed in an effort to solicit opinion from the general public, with one survey being conducted after publication of the draft 2007 policy. The data collection methods used for these surveys ensured wider public participation and thus popular control over the policy issue under discussion. Therefore, we are justified in advancing the characterization of the 2007 process from the sectorization label we give to the 1999 policy formulation exercise. Our third reason is that while the 2007 policy making process was more open in terms of interaction between the government and society, there seems to be no indication that a culture of consultation has been institutionalized to such an extent that an exchange regime has been established for future policy making. In particular, the public consultation process undertaken in 2007 did not include any input from interest groups from the business, trade or social welfare realms. Therefore, taking account of the qualified significance of public submissions made during the 2007 policy making process, as shown by the Chi-Square test described above, the 2007 regime is best characterized as a consultation process that represents some degree of progress from the sectorization approach adopted in 1999, but not much more.

5. Discussion and implications

This study examines the issue of changes seen in the policy making process in the specific context of the Chinese golden week holiday system. Our findings both echo existing theoretical elaborations and explain Chinese peculiarities. First, the findings corresponding to the first research objective, for which the results demonstrate a significant change in the dominant policy demands taken into account in the respective policy making processes undertaken in 1999 and 2007, consolidate theoretical discussions on policy change that analogize the policy process as a dynamic equilibrium with policy punctuations being the norm rather than the exception (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993). Meanwhile, classical theoretical discourses designate policy changes as responses to the occurrence of abrupt major incidents known as potential focusing events (PFEs) (Birkland, 1997). However, the policy change observed in this study seems to have been influenced by a cohort of complex and sometimes competing demands which were triggered not only by a number of PFEs, but also by factors of a more incremental nature. Such a complex group of forces influencing policy change may be accounted for by the Chinese leadership's traditional emphasis on ‘gradual and prudent decision making’ (Wu, 2005, p. 67). Future studies on the policy making mechanisms for other social phenomena may provide further evidence confirming this view or result in complementary insights.

While economic concerns were the main focus of the agenda in the 1999 policy making process, the focus in 2007 had moved toward social issues, although subject to the proviso that core economic concerns not be compromised. This policy punctuation, which was shaped by shifting policy demands, can be better comprehended through a deeper inquiry into the contextual transformations seen in the wider Chinese policy environment during the time span for our study. It seems that the ideological vicissitudes undergone in Chinese society from 1999 to 2007 convincingly account for the shift from economic demands to social ones in golden week policy making. Ideological stipulations legitimize the intellectual and emotional pressures for change to the current social system (Cameron, 1978), and Chinese society has long been framed by and responsive to the guiding political ideologies of the Communist Party of China (CPC) (Li, 2006). The 1999 policy was formulated under the ideological context of Deng Xiaoping Theory, which emphasized the core status of economic construction (Jiang, 1997); economic demands thus overwhelmed social considerations in the 1999 policy formulation process.

However, the current CPC leadership, which has occupied the central political stage since early 2003, has been advocating and mobilizing for new ideological discourses which can be summed up as a ‘scientific outlook on development’. The new discourses, while still stressing the importance of economic construction, further require that people's well-being be placed at the core, and stress the comprehensive, balanced, and sustainable development of ‘a harmonious socialist society’ as reflected by all-round improvements in Chinese people's quality of life (Hu, 2007). As Table 2 shows, such people-oriented approaches are conspicuous in the social demand sub-categories for the 2007 policy, such as promoting traditional Chinese culture, realizing human rights to leisure time, and learning from international practice. Furthermore, even the economic considerations taken into account for the 2007 policy make reference to sustainability values such as balanced development and equal opportunity. What is particularly worth noting here is the specific timing of the promulgation of the 2007 policy—December 2007, which was only one month after the convention of the 17th National Congress of the CPC, where the ‘scientific outlook on development’ ideology was formally proposed. This short interval may have been emblematic of the considerable and immediate impact of ideological shifts on the legitimacy of the policy changes made in the 2007 regulation. Finally, the ‘scientific outlook on development’ approach is still seen as an integral advance based on Deng Xiaoping Theory; such ideological harmony may have accounted for the partial policy changes made in 2007 whereby the May Day golden week was abolished and the other two golden week retained.

When it comes to the answers to the second research objective dealing with the weight of tourism demands in the golden week holiday system policy making, this study demonstrates the marginalization of tourism demands in the 1999 and 2007 policy making agendas. What is more, the tourism industry took much of the blame for the negative effects of the golden week in the 2007 policy formulation process. Existing theoretical elaborations attribute the muted voice of tourism in public policy making to the inherent features of the tourism industry, with a dispersed and diffuse set of stakeholders which makes it difficult for the formation of synchronized industrial representations in the political spectrum (Jeffries, 2001). In addition, the current ideological ethos in many developed countries in which the tourism industry is regarded as an industry that suits self-regulation in a market economy have biased official attitudes toward tourism policies (Goeldner & Ritchie, 2003). The bureaucratic roles of many national tourism administrations in such countries have been substantially blurred, as such organizations have been reformed into entities operated like public enterprises (Mill & Morrison, 1998).

The Chinese characteristics revealed by this study may be further explained by the traditional disjointed nature of public policy making in China, which complicates the picture of bureaucratic competition over the control of certain social phenomena (Dreyer, 2004; Nicholson-Crotty, 2005). The deputy-ministerial rank of the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA) under the Chinese central government was also a factor in the low degree of influence the CNTA has in policy making on golden week. For instance, in addition to the CNTA, there are 13 ministerial departments that have jurisdiction over the administration of tourist attractions in China (Zhang et al., 2005), and it has been admitted that across the whole Chinese tourism industry, only the hotel and travel agency sectors are within the exclusive realm of the CNTA (Gao, 2006).

Nevertheless, it is particularly ironic that the findings of this study show that a strange mix of tourism policy has been observed: tourism concerns were not meant to occupy the central stage in the 1999 policy making process, yet the 1999 policy was retrospectively bestowed with the splendid title of ‘the golden week’, mostly because of their effect in stimulating Chinese domestic and outbound tourism. The changes made to the policy in 2007, as embodied in the abolition of the May Day golden week, were partly stimulated by the public angst about the negative tourism impact the policy had had, notwithstanding the supportive stance of the CNTA in lobbying for the retention of the 1999 policy. This shows the pronounced contrast between the considerable weight attached to and debate over tourism-related policies among the general public on one hand, and the limited leverage of the tourism authorities within the Chinese bureaucracy on the other. With soaring demand for travel among the Chinese people as a result of sustained economic growth, it remains to be seen whether such a gap will induce a fundamental transformation of the Chinese tourism policy arena, and more research on this point would be worthwhile and insightful, especially if the role played by the CNTA in other Chinese tourism policy issues is investigated on comparative and longitudinal bases.

In terms of the results on the third research objective dealing with the interaction between the government and the public in golden week holiday policy making, our respective characterizations of the 1999 and 2007 processes as sectorization and consultation demonstrate that some new developments were seen in the Chinese public policy making process during the research period. Our results show that the Chinese government, with its unique system of centralized party-state dualism in public governance matters, became more willing to bring other policy actors or interested parties into the policy making process in 2007. This study, which examines an isolated case, also demonstrates that such an ‘opening-up’ of the policy making process is still carried out on quite a limited and well-controlled basis. This indicates that further empirical studies should be carried out to ascertain whether this new consultation model can remain stable or even become institutionalized as the policy making mechanism for other social phenomena in China. Further research is also merited into whether the consultation regime discussed here can undergo additional paradigm shifts along the theoretical scale outlined above, recognizing the general trend toward deeper economic liberalization in China as a socialist market economy is established. Looming together with this prospect is the integration into this regime of emerging vested interests in an organized form in China, whose existence and legitimacy have been only ambiguously recognized by the Chinese authorities (Liu, 2006). Nevertheless, in the Western context, interest groups are believed to be on the cusp of assuming greater power to influence citizen participation models in the deliberative process of public policy making (Ellison, 1998). Interest groups in Western contexts have been particularly sophisticated in affecting public policy making and have been accounted for by structures like the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) and policy networks (Ellison, 1998, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1999, Tyler and Dinan, 2001). Further research aimed at tracking the development of organized interest groups in China and their function in the formulation of Chinese public policy would provide for interesting insights.

This study has a number of limitations that should be discussed here. First, on the specific research methodologies employed in this study, despite the efforts of the authors during the analysis stage, content analysis has long been criticized for its neglect of semantic structure, inflation of the theme count, and lack of sensitivity (Neuendorf, 2002). Also, due to time, financial and social network constraints, the limited access possessed by the authors to data sources for this study may have undermined the validity of the research results. While the amounts of text units out of the 45 collected documents have been deemed sufficient pursuant to the research purposes of this study, the validity of the research results of this study would be greatly enhanced if more primary research resources could be secured. In addition, the lack of established criteria for evaluating research objective 3 may have weakened the subjective conclusions reached by the authors. Thus, the research design required the use of more rigorous research methodologies that could better accommodate the research objectives and more credible data sources. Third, with regard to the conceptual framework for the study, taking into account the growing influence of external factors on the Chinese policy subsystem, which has been undergoing a fundamental transformation with the deepening of the reform and opening-up of the economy and the establishment of a socialist market economy, the introduction and due investigation of foreign components may further complement the existing framework by giving a more comprehensive picture of contemporary Chinese policy making, especially the 2007 mechanism. Finally, in response to the call for policy analysis from a panoramic perspective, research undertaken on a more extended longitudinal basis that covers the policy implementation stage will surely help develop a more thorough understanding of the Chinese policy making mechanism.

6. Conclusion

While vacation policies in many Western societies have been established and remained stable for over a half century now, major changes in this policy area have been recorded only recently in China, with the most salient one being the golden week holiday system first introduced in 1999 and later amended in 2007. This study, by examining the respective golden week holiday policy making mechanisms adopted in 1999 and 2007, contributes to the building of theory on the mechanism for public policy changes in the Chinese context, demonstrating both consistency with existing theoretical elaborations and unique Chinese characteristics. In particular, given that the golden week debate remains contentious, even after the policy process undertaken in 2007, the three dimensions identified by this study may lay a tenable foundation for studies on future golden week holiday policy changes. Second, this study complements current research on tourism policies, particularly due to its confirmation of the comparatively muted voice of tourism interests in public policy issues, even where the tourism stakes are high. The tourism dimensions of the golden week policy making mechanisms used in the two years examined played only a peripheral role in the policy changes effected. This study may have significant implications for tourism authorities in other developing countries that are reliant on tourism development to balance tourism priorities with other competing interests in initiating relevant policies.

On the practical side, this study can serve as a reference for foreign stakeholders interested in tourism development in China, enabling them to gain a better appreciation of and thus benefit to a greater degree from the policy making process in contemporary China. In particular, the golden week have become important windows for an increasing number of Chinese outbound tourists to travel to destinations all around the world (Gao, 2006). Hence, a better understanding of the mechanism driving vacation policies in China will be of value to all foreign parties eager to gain a larger share of this lucrative market.

Appendix. Major differences between the 1999 and 2007 regulations on the golden week holiday

| 1999 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of annual holidays | 10 | 11 |

| Number of de facto annual week-long holidays | 3 | 2 |

| Regulation of formation of long holidays | None; one-off regulations each time | Institutionalized |

| Other regulation(s) released together | None | Ordinances on paid vacations of employees |

References

- ACNielsen China outbound travel monitor 2007. 2007. http://cn.en.acnielsen.com/site/1023e.htm Retrieved October 28, 2007, from.

- Anderson C.W. Wiley; New York: 1976. Statecraft: An introduction to political choice and judgment. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner F.R., Jones B.D. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1993. Agendas and instability in American politics. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland T.A. Georgetown University Press; Washington, DC: 1997. After disaster. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J.M. Ideology and policy termination: Restructuring California's mental health system. Public Policy. 1978;38(4):533–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.M., Dickson B.J., editors. Remaking the Chinese State: Strategies, society, and security. Routledge; London, New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.S., Kerstetter D.L., Graefe A.R. Tourists' reasons for visiting industrial heritage sites. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing. 2001;8(1/2):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.Y., Li Y.P. Empirical analysis of the golden week holidays system and model for reform of vacation policies. Consumer Economics. 2007;23(5):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke P., Perkins H.C. Commodification and adventure in New Zealand tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. 2002;5(6):521–549. [Google Scholar]

- CNTA (The China National Tourism Administration) China Tourism Press; Beijing: 2008. The yearbook of China tourism statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb R.W., Elder C.D. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 1972. Participation in American politics: The dynamics of agenda building. [Google Scholar]

- Davis G., Wanna J., Warhurst J., Weller P. Public policy in Australia. 2nd ed. Allen & Unwin; St. Leonards: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Derocco D., Dundas J., Zimmerman I. Full Blast Productions; Virgil, Ontario: 1996. The International holiday & festival primer: Book 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison B.A. The advocacy coalition framework and implementation of the Endangered Species Act: a case study in western water politics. Policy Studies Journal. 1998;26:11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Anderson G. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. [Google Scholar]

- Fayos-Sola E., Bueno A.P. Globalization, national tourism policy and international organizations. In: Cooper C.P., Wahab S., editors. Tourism in the age of globalization. Routledge; London: 2001. pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gao S.L. China Tourism Publishing House; Beijing: 2004. Opening strategy research on China tourism industry. [Google Scholar]

- Gao S.L. China Tourism Publishing House; Beijing: 2006. Studies on policies of the tourism industry in China. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. A historical account of vacation policies in the world. Government Legal System. 2007;9(2):32. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod B. Defining marine tourism: a Delphi study. In: Garrod B., Wilson J.C., editors. Marine tourism: Issues and experiences. Channel View Publications; Clevedon, UK: 2003. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Geva-May I. Riding the wave of opportunity: termination in public policy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2004;14(3):309–333. [Google Scholar]

- Goeldner R.C., Ritchie J.R.B. Tourism: Principles, practices, philosophies. 9th ed. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Graddy E.A., Ye K. When do we “Just Say No”? Policy termination decisions in local hospital services. Policy Studies Journal. 2008;36(2):219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gray J.H., Densten I.L. Integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis using latent and manifest variables. Quality and Quantity. 1998;32(4):419–431. [Google Scholar]

- Green F., Potepan M.J. Vacation time and unionism in the U.S. and Europe. Industrial Relations. 1988;27:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M. Belhaven Press; London: 1994. Tourism and politics: Policy, power and place. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Jenkins J.M. Routledge; London, New York: 1995. Tourism and public policy. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Valentin A. Content analysis. In: Ritchie B.W., Burns P., Palmer C., editors. Tourism research methods: Integrating theory with practice. CABI Publications; Cambridge, MA: 2005. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.C. Terrorism and tourism: managing the consequences of the Bali bombings. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing. 2003;15(1):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. Harvester Wheatsheaf; New York: 1993. The policy process: A reader. [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.T. People Press; Beijing: 2007. Report to the opening ceremony of the seventeenth national congress of the Chinese Communist Party. [Google Scholar]

- Insch G.S., Moore J.E. Content analysis in leadership research: Examples, procedures and suggestions for future use. Leadership Quarterly. 1997;8(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries D. Butterworth-Heinemann; Boston: 2001. Governments and tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G. (2001). Tourism research. Milton, Qld.: Wiley Australia.

- Jiang Z.M. People Press; Beijing: 1997. Report to the opening ceremony of the fifteenth national congress of the Chinese Communist Party. [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.O. 2nd ed. Duxbury; North Scituate, MA: 1977. An introduction to the study of public policy. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan G., Richardson J. The British policy style or the logic of negotiation. In: Richardson J., editor. Policy Styles in Western Europe. George Allen and Unwin; London: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Li P. Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Academy Press; Beijing: 2006. Public administration. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.X., editor. Public policy analysis. Dongbei University of Finance & Economics Press; Dalian: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McBeth M.K., Shanahan E.A., Arnell R.J., Hathaway P.L. The Intersection of narrative policy analysis and policy change theory. Policy Studies Journal. 2007;35(1):87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mill R.C., Morrison A.M. The tourism system: An introductory text. 3rd ed. Kendall/Hunt; Dubuquue, Iowa: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf K.A. Sage; Thousand Oaks, California: 2002. The content analysis guide book. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson-Crotty S. Bureaucratic competition in the policy process. The Policy Studies Journal. 2005;33(3):341–361. [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke D. Outsourcing regulation: analyzing nongovernmental systems of labor standards and monitoring. The Policy Studies Journal. 2003;31(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. Multi-language Media, Inc.; Philadelphia: 2004. A look inside America: Exploring America's cultural values and holidays. [Google Scholar]

- Ren P. The analysis of gains and losses for travel in the gold week. Journal of Mianyang Normal University. 2007;26(7):18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Renn O., Webler T., Wiedemann P. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 1995. Fairness and competence in citizen participation: Evaluating models for environmental discourse. [Google Scholar]

- Richards G. Vacations and the quality of life: patterns and structures. Journal of Business Research. 1999;44:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C.W. A conceptual framework for quantitative text analysis. Quality and Quantity. 2000;34(3):259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P.A., Jenkins-Smith H.C. The advocacy coalition framework: an assessment. In: Sabatier P., Jenkins-Smith H.C., editors. Theories of the policy process. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1993. pp. 117–166. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel N. Free time in France: a historical and sociological survey. International Social Science Journal. 1993;107:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Schor J. Basic Books; New York: 1991. The overworked American: The unexpected decline of leisure. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P.A., Jenkins-Smith H.C. The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In: Sabatier P.A., editor. Theories of the policy process. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shao Q.W. Speech on the national tourism work meeting 2008. CNTA Web News. 2008. <http://www.cnta.gov.cn> Accessed 3 May 2008.

- Sheng Z.F. Key points for the sustainable development of tourism during the golden week holidays. Journal of the Hunan First Normal College. 2005;12:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Simon H. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA.: 1997. Administrative behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Sirakaya E., Soenmez S. Gender images in state tourism brochures: an overlooked area in socially responsible marketing. Journal of Travel Research. 2000;38(4):353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler D., Dinan C. The role of interested groups in England's emerging tourism policy network. Current Issues in Tourism. 2001;4:210–252. [Google Scholar]

- Veal A.J. Pearson Education Limited; London: 2006. Research methods for leisure and tourism: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S., Pigram J. Routledge; London: 1997. Tourism development and growth. [Google Scholar]

- Weber R.P. Sage; Beverly Hills, C.A.: 1985. Basic content analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Webler T. ‘Right’ discourse in citizen participation: an evaluative yardstick. In: Renn O., Webler T., Wiedemann P., editors. Fairness and competence in citizen participation: Evaluating models for environmental discourse. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 1995. pp. 35–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wick I. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; Bonn, Germany: 2001. Workers' tool or PR ploy? A guide to codes of international labour practice. [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.G. Marshall Cavendish Academic; Singapore: 2005. The anatomy of political power in China. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi C. How tourists see other tourists: analysis of online travelogues. The Journal of Tourism Studies. 2001;12(2):22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. The rational return of tourism during the golden week holidays. Tourism Science. 2005;2:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.M. The revelation of the USA holiday pattern to the Chinese holiday pattern. Si Xiang Zhan Xian. 2006;32(2):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.Q., Pine R., Lam T. The Haworth Press Inc.; New York: 2005. Tourism and hotel development in China: from political to economic success. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.M., editor. Introductive studies on public policy science. China People University Press; Beijing: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Cameron G.T. China' agenda building and image polishing in the US: assessing an international public relations campaign. Public Relations Review. 2003;29(1):13–28. [Google Scholar]