Neither law nor religion, bioethics absorbs and applies elements of both. Its theories, principles, and methods stem from various philosophical schools. Practitioners use case-based reasoning to apply bioethics to clinical situations, usually giving most weight to patients' autonomy and values, but also incorporating other relevant bioethical principles, including those encompassed in professional oaths and codes [1]. Emergency clinicians must be able to recognize bioethical dilemmas, have action plans based on their readings and discussions, and have a method through which to apply ethical principles in clinical settings.

What is bioethics?

Ethics is the application of values and moral rules to human activities. Bioethics is a subset of ethics that provides reasoned and defensible solutions that incorporate ethical principles for actual or anticipated moral dilemmas facing clinicians in medicine and biology. Unlike professional etiquette, which relates to standards governing the relationships and interactions between practitioners, bioethics deals with relationships between practitioners and patients, practitioners and society, and society and patients [1].

Modern bioethics has developed during the last four decades largely because the law has often remained silent, inconsistent, or morally wrong on matters vital to the biomedical community. The rapid increase in biotechnology, the failure of both the legal system and the legislatures to deal with new and pressing issues, and, in the United States, the increasing liability crisis have driven the medical community to seek answers to some of the difficult questions practitioners have had to work through on a daily basis [1]. The clinical application of bioethics relies on case-based (casuistic) reasoning, in general favoring patients' autonomy and values, but also considering other relevant bioethical principles, including those values inscribed in communal ethics and professional oaths and codes. It is incumbent upon emergency physicians, whenever possible, to determine not only each patient's individual values, but also whether the patient subscribes to an individualistic or a communitarian ethic. Such determinations may help decide who the most appropriate decision makers will be if the patient lacks the capacity to make his or her own decisions.

Relationship between law and bioethics

Both the law and bioethics give us rules of conduct to follow. Yet, there are significant differences between the two. Laws stem from legislative statutes, administrative agency rules, or court decisions. They often vary in different locales and are enforceable only in the jurisdictions where they prevail. Ethics incorporates the broad values and beliefs of correct conduct. Although bioethical principles do not change because of geography (at least not within one culture), the interpretation of both ethical and legislative principles may evolve as societies change. But, while good ethics often makes good law, good law does not necessarily make good ethics. Most laws, while based loosely on societal principles, are actually derived from other laws. Ethical principles, however, are derived from the values of the society in which they are proposed.

Confusion often arises about the differences between law and bioethics for three reasons. The first is that Western, and especially US and Canadian, bioethics discussions often use legal cases to bolster their points because, unlike ethical discussions in most published medical cases, legal cases provide rich details for ethical discussion and deliberation. The second is that legal cases provide an insight into our social contract, demonstrating the level of societal acceptance of some knotty issues. Finally, in a democratic society, the law provides an avenue through which bioethical policy can be expressed and codified across a large region.

Law and ethics: similarities and differences

Significant overlap exists between legal and ethical decision-making ( Table 1). Both ethical analysis (in bioethics committee deliberations) and the law (in the courts) use case-based reasoning in an attempt to achieve consistency. Legal and ethical dicta have existed since ancient times, have evolved over time, incorporate basic societal values, and form the basis for policy development within health care as well as in other parts of society.

Table 1.

Relationship between law and bioethics

| Bioethics | Function | Law |

|---|---|---|

| ✓ | Case-based (casuistic) | ✓ |

| ✓ | Has existed from ancient times | ✓ |

| ✓ | Changes over time | ✓ |

| ✓ | Strives for consistency | ✓ |

| ✓ | Incorporates societal values | ✓ |

| ✓ | Basis for healthcare policies | ✓ |

| Some unchangeable directives | ✓ | |

| Formal rules for process | ✓ | |

| Adversarial | ✓ | |

| ✓ | Relies heavily on individual values | |

| ✓ | Interpretable by medical personnel | |

| ✓ | Ability to respond relatively rapidly to changing environment |

From Iserson KV. Principles of biomedical ethics. In: Marco CA, Schears RM, (editors.) Ethical issues in emergency medicine. The Emergency Clinics of North America 1999;17(2):285; with permission.

The law and bioethics differ markedly, however, in some areas. For instance, the law operates under formal adversarial process rules, such as those in the courtroom, which allow little room for deviation, while bioethics consultations are flexible enough to conform to the needs of each institution and circumstance and, rather than being adversarial, are designed to assist all parties involved in the process. The law also has some unalterable directives, sometimes called “black-letter laws,” that require specific actions. Bioethics, while based on principles, is designed to weigh every specific situation on its own merits. Perhaps the key difference between bioethics and the law is that bioethics relies heavily on the individual's values—be they those of the patient or of the patient's surrogate. Also, even without the intervention of trained bioethicists, medical personnel can and should be able to make ethically sound decisions. The law does not consider individual values and generally requires lawyers for interpretation.

As previously noted, a reason for the development of bioethics, and a key difference between bioethics and the law, is the former's ability to respond to a rapidly changing health care environment.

Rights

Despite their differences, there is frequently concurrence between bioethics and the law on basic issues. On occasion, clarity within the law can lead to clearer thinking in bioethics (and vice versa). Both law and bioethics, for example, use the term rights, as in “patients' rights” and “the right to die.” This term, often used to advance an ethical argument about medical care, is frequently misunderstood or applied erroneously. Having a right implies that a person, group, or the state has a corresponding moral and legal duty. Without a duty to act, there can be no rights. The rights can either be positive, dictating that a person or group act in a specific manner, or negative, requiring that they refrain from acting. Legal requirements, other authorities, or individual conscience can bestow rights, an act that requires a corresponding duty by those with the power to act, such as health care providers [2]. This obligation to act can be based upon an individual's personal values, professional position, or other commitment [3]. For the physician, this duty to act is a role responsibility, at least when holding oneself out as a physician—and possibly at all times. The role–duty link occurs “whenever a person occupies a distinctive place or office in a social organization, to which specific duties are attached to provide for the welfare of others or to advance in some specific way the aims or purposes of the organization” [4]. In this circumstance, performance is not predicated on a guarantee of compensation, but on a concern for another person's welfare [5]. The emergency physician has just such a duty.

Relationship between religion and bioethics

In homogenous societies, religions have long been the arbiters of ethical norms. Western societies, however, are multicultural, with no single religion holding sway over the entire populace. Therefore, a patient-value–based approach to ethical issues is necessary. Yet, religion still influences bioethics. Modern bioethics uses many decision-making methods, arguments, and ideals that draw from religious principles. In addition, clinicians' personal spirituality may influence their relationships with patients and families in crisis.

While various religions may appear dissimilar, most have a form of the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” as a basic tenet. Other moral rules common to most religions are listed in Box 1. Problems surface when trying to apply religion-based rules to specific bioethical situations. For example, although “Do not kill” is generally accepted, the interpretation of the activities that constitute killing, active or passive euthanasia, or merely reasonable medical care varies among the world's religions, as it does among various philosophers [6].

Box 1. Commonly accepted moral rules.

Moral rules govern actions that would be considered immoral without an adequate moral reason. Such rules can justifiably be enforced and their violation punished. Although none of these rules is absolute, each requires that a person not cause evil. Somewhat paradoxically, however, the rules may neither require preventing evil nor doing good.

-

•

Do not kill.

-

•

Do not cause pain.

-

•

Do not disable.

-

•

Do not deprive of freedom.

-

•

Do not deprive of pleasure.

-

•

Do not deceive.

-

•

Keep your promise.

-

•

Do not cheat.

-

•

Obey the law.

-

•

Do your duty.

Adapted from Gert B. Morality: a new justification of the moral rules. New York, Oxford University Press, 1988. p. 157; with permission.

Over time, the Western world, and especially the United States, has turned away from a uniform reliance on religious principles and toward secular principles for answers. The medical community has been no exception. Several such principles, such as autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and fairness, are now generally accepted. These have guided ethical thinking and have been instrumental in forming health care policies in the United States and other Western countries over the past three decades.

Ethical theories

Ethical traditions stretch back to earliest recorded history. Separate bodies of ethics, often encompassing a general system rather than a true theory, were developed in India and China, and within the Jewish, Christian, Islamic, and Buddhist religions. All these theories represent altruistic, rather than egoistic, attitudes toward mankind. Ethical theories represent the grand ideas on which guiding principles are based, attempting to be coherent and systematic, while striving to answer fundamental, practical questions: What ought I do? How ought I live? Ethicists normally appeal to these principles, rather than the underlying theory, when defending a particular action. Western bioethics continues to encompass a number of theories, some quite contradictory. Some of the most commonly cited include:

Natural law. This system, often attributed to Aristotle, posits that man should live life according to an inherent human nature. It can be contrasted with man-made, or judicial, law. Yet, they are similar in that both may change over time, despite the frequent claim that natural law is immutable [7].

Deontology. This theory holds that the most important aspects of our lives are governed by certain unbreakable moral rules. Deontologists hold that these rules may not be broken, even if breaking them may improve an outcome. In other words, they may do the “right” thing, even though the consequences of that action may not be “good.” The famous philosopher, Immanuel Kant, is often identified with this theory. One example of a list of “unbreakable” rules is the Ten Commandments [8].

Utilitarianism. One of the more functional and commonly used theories, utilitarianism, sometimes called consequentialism or teleology, promotes good or valued ends, rather than using the right means. This theory instructs adherents to work for those outcomes that will most advantage the majority of those affected in the most impartial way possible. Utilitarianism is often simplistically described as advocating methods to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people. It is often advocated as the basis for broad social policies [9].

Virtue theory. This theory asks what a “good person” would do in specific real-life situations. This recently revived theory stems from the character traits discussed by Aristotle, Plato, and Thomas Aquinas. They discuss such timeless and cross-cultural virtues as courage, temperance, wisdom, justice, faith, and charity. Recently, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine took the unusual step of adopting a virtue-based code of conduct ( Box 2) [10].

Other theories. Other ethical theories are rarely applied within the scope of bioethics, and each has serious, if not fatal, flaws. Rights theory is based on respecting others' rights. The social contract tradition is based on the implicit agreement we make with others to exist in a cooperative society. Prima facie duties, although less rigid than deontology, lays down certain duties each person has toward others. Egoism advocates that each person live so as to further his or her own interests, a theory in direct opposition to altruism.

Box 2. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Ethical Code: a code of conduct for academic emergency medicine.

As a member of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), I am committed to serve humanity. I will practice my art with conscience and virtue, keeping patient welfare my first consideration. I will be considerate, forthright, and just in all of my dealings with patients and colleagues, regardless of their power, position, or station in life. I will maintain the utmost respect for human dignity. I will strive to safeguard the public health and protect the vulnerable. I will advance the ideals of the profession, and I will not abuse the privilege of my knowledge or position. In addition to these general professional obligations,

As a researcher of emergency medicine, I vow

-

•

Competence, conducting scientifically valid research that, before all else, benefits patients and society.

-

•

Compassion, attending humanely to the comfort and dignity of all subjects, animal or human.

-

•

Respect, securing the safety, privacy and personal welfare of human subjects, and offering informed choice whenever possible.

-

•

Impartiality, treating fairly all those associated with the research process, including subjects and nonsubjects, coinvestigators, and potential authors, and being neither too eager to promote nor too quick to condemn new scientific concepts.

-

•

Integrity, reporting promptly any scientific fraud or misconduct, publishing only accurate, uninflated results, and resisting conflicts of interest and the lure of personal gain.

-

•

Responsibility, advancing the boundaries of emergency medical science and taking care to use prudently the resources entrusted to me for this purpose.

As a teacher of emergency medicine, I vow

-

•

Altruism, generously sharing the art and science of emergency medicine for the betterment of others and the honor of the calling.

-

•

A commitment to excellence, maintaining my technical expertise and moral sensitivity through continued study and practice.

-

•

Respect, giving all who seek to learn emergency medicine the dignity due a colleague.

-

•

Fairness, treating all students and fellow teachers equitably, in a manner free of prejudice, abuse, or coercion.

-

•

Honesty, imparting truth and uncertainty openly, and identifying clearly for my patients all trainees and students involved in their care.

-

•

Mentorship, nurturing and encouraging the requisite technical, intellectual, and moral virtues of the profession in students of every kind through my words and deeds.

By keeping these promises, may I bring honor to myself and my profession, enriching the lives of patients, students, and colleagues.

From Larkin GL, SAEM Ethics Committee. A code of conduct for academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:45; with permission.

Values and principles

Where are values and principles learned?

Values are the standards by which we judge human behavior. They are, in other words, moral rules, promoting those things we think of as good and minimizing or avoiding those things we think of as bad. We learn these values, usually at an early age, from observing behavior and through secular (including professional) and religious education. While many of these learned values overlap, each source often claims moral superiority over the others, whether the values stem from generic, cultural, or legal norms; religious and philosophical traditions; or professional codes [11]. Societal institutions incorporate and promulgate values, often attempting to rigidify old values even in a changing society. In a pluralistic society, clinicians often treat individuals having multiple and differing value systems and they must be sensitive to others' beliefs and traditions.

Ethical values stem from ethical principles. These principles are “action guides” derived from ethical theories, each consisting of various “moral rules,” which are our learned values [12]. For example, the values of dealing honestly with patients; fully informing patients before procedures, therapy, or research participation; and respecting the patient's personal values are all subsumed under the principle of autonomy (respect for persons).

A question that naturally arises is whether ethical principles are universal. This is an important question in bioethics, since clinicians must treat patients from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Philosophers once scorned the idea that there were contradictory ethical principles in different cultures. Yet, today, there is a growing acceptance that such differences exist [13]. This discussion, however, will concentrate on those ethical principles generally accepted in Western cultures.

Although each individual is entitled and perhaps even required to have a personal system of values, there are certain values that have become generally accepted by the medical community, courts, legislatures, and society at large. Although some groups disagree about each of these, this dissension has not affected their application to medical care. A respect for patients (often described as patient autonomy) has been considered so fundamental that it is often given overriding importance. Other frequently cited values are beneficence and nonmaleficence.

Why are patient values important?

A key to making bedside ethical decisions is to know the patient's values. As members of democracies with significant populations practicing a number of religions and subgroups of those religions, Western emergency medical practitioners must behave in a manner consistent with the values of each patient. While many people cannot answer the question, “What are your values?,” physicians can get an operational answer by asking what patients see as the goal of their medical therapy and why they want specific interventions. The underlying question must be: “What is the patient's desired outcome for medical care?” Responses from patients represent concrete expressions of patient values. In patients too young or incompetent to express their values, it may be necessary for physicians to make general assumptions about what the normal person would want in a specific situation or to rely on surrogate decision-making. However, with patients who are able to communicate, care must be taken to discover what they hold as their own, uncoerced values. A typical, ethically dangerous scenario involves a patient who refuses lifesaving medical intervention “on religious grounds.” Commonly, the spouse is at the bedside, does most of the talking, and may be influencing the patient's decisions. In those cases, it is incumbent on the clinician to re-question the patient to assess his or her real values in that situation.

Not only religion, but family, cultural, and other values contribute to patients' decisions about their medical care. Without asking, there is no way to know what decision a patient will make. It is important to note that religion influences modern secular bioethics, which uses many religion-originated decision-making methods, arguments, and ideals. In addition, clinicians' personal spirituality may allow them to relate better to patients and families in crisis.

Clinicians' and institutional values

Institutions, including health care facilities and professional organizations, also have their own value systems. Health care facilities, although relatively well standardized under the requirements of regulatory bodies and government agencies, often have specific value-related missions. Religiously oriented or affiliated institutions may be the most obvious of these, but charitable, for-profit, and academic institutions also have specific role-related values. The values that professional organizations aspire to are often set forth in their ethical codes, described later in this article.

On a wider, but individual basis, some medical centers deny treatment (or at least admission through the emergency department) on internal medicine, family practice, and pediatric teaching services based on arbitrary resident work limits. “Capping” is commonly used to describe prescribed resident work limits, a relatively new practice that, in its current form, is damaging the physician educational system and possibly the professionalism of medicine. It involves two elements: (1) restricting residents' work hours, and (2) limiting the number of patients that can be admitted or the number of inpatients for whom residents can be responsible [14].

Clinicians have their own ethical values, as do professional organizations and health care institutions. Conscience clauses permit clinicians to “opt out” when they feel that they have a moral conflict with professionally, institutionally, or legally required actions. These conflicts, which may have a religious, philosophical, or practical basis, prevent them from following the normal ethical decision-making algorithm. When such conflicts exist, it is morally and legally acceptable, within certain constraints, for the individual to follow a course of action based upon his or her own value system. The constraints generally require that there be the provision of timely and adequate medical care for the patient, which may be particularly difficult to achieve in emergency medicine. The most common conflict has been about whether to provide emergency contraception. Consensus generally discourages delaying necessary medical treatments, including emergency contraception, since patients often have no choice about the emergency department to which they go and cannot know the practitioners' attitudes about such treatment in advance [15], [16]. When conflicts over values exist, however, it is essential for the practitioner to recognize the patient's identity, dignity, and autonomy to avoid the error of blindly imposing one's own values on others.

While it is tempting to use the latest instruments or medications, physicians have a duty to maintain competency in new technologies and be informed of new medications to decrease any potential risks before subjecting their patients to them. Since there is relatively little oversight of individual practitioners in this area, it remains substantially a matter of personal ethics [17].

Over the millennia, personal values have dictated whether a physician would remain with his or her patients during extreme or catastrophic circumstances. Physicians, even such legends of medicine as Galen, often fled to save their own lives. In the era of modern epidemics of unknown virulence and etiology, the question of whether physicians will stay and treat patients remains a personal moral decision. This issue is of special concern for emergency physicians in the front line of these medical assaults.

Autonomy

Definition and basis

Individual freedom is the basis for the modern concept of bioethics. This freedom, usually spoken of as “autonomy,” is the principle that a person should be free to make his or her own decisions. It is the counterweight to the medical profession's long-practiced paternalism (or parentalism), wherein the practitioner acted on what he thought was “good” for the patient, whether or not the patient agreed. The principle of autonomy does not stand alone, but is derived from an ancient foundation for all interpersonal relationships—a respect for persons as individuals.

Physicians have only grudgingly begun to accept patient autonomy in recent years. From three perspectives, this is understandable. First, accepting patient autonomy means that physicians' roles must change. They must be partners in their patients' care rather than the absolute arbiters of the timing, intensity, and types of treatment. Second, they must become educators, teaching their lay patients enough about their diseases and treatments to make rational decisions. Finally, and most distressing to clinicians, is accepting that some patients will make what clinicians consider to be foolish choices. For physicians dedicated to preserving their patients' well being, allowing people to select what the physician considers poor treatment options (such as refusing treatment or opting for ineffective regimens) may be both frustrating and disheartening. Yet, allowing these “foolish” choices is part of accepting the principle of patient autonomy. If clinicians fully understand patient autonomy, much of the rest of clinical bioethics naturally follows.

Communitarianism—an alternate view of life

Both a philosophical and a political value, communitarianism is the belief that the standards of justice must be based on the life and traditions of a particular society and how that society views the world. Key to this concept is the understanding that cultural factors can affect how people prioritize and justify rights. This different prioritization becomes vitally important during ethical dilemmas, when values often conflict. The application of one set of values instead of another may lead to radically different outcomes. In contrast to the Western emphasis on autonomy, communitarians cleave to the Aristotelian view that “Man is a social animal, indeed a political animal, because he is not self-sufficient alone, and in an important sense is not self-sufficient outside a polis.”

Typical communities may be related to one another by geographical location, a morally significant history, or may work together for common goals in a trusting and altruistic manner. In practice, communitarian values are found in many patients presenting to emergency departments who have close family interrelationships and whose sense of self is bound to their communities. This example of communitarianism most frequently occurs with patients from outside the United States. Given the Western emphasis on autonomy, the best way to function with those patients displaying a communitarian ethic is to recognize this as their autonomous wish and to follow it. This means accepting the communitarian ethic of involving family in consultations and relying on senior or other family members for making decisions affecting the patient.

Decision-making capacity, consent, and surrogates

When patients cannot make their own health care decisions, others must make such decisions for them. Two questions arise: When do patients lack such capability? Who then makes the decision?

Patients may exercise their autonomy only if they have the mental capacity to do so. Justice Benjamin Cardozo stated this principle of both bioethics and the law early in the last century: “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body …” [18]. Only if we understand how to determine decision-making capacity can we use the principle of patient autonomy in clinical practice. In emergency medicine, questions of decision-making capacity frequently arise for issues of informed consent, patient refusals (often in the emergency medical services system), and patient discharge from the emergency department.

We often mistakenly use the word competency when we mean capacity. “Competency,” like the word “insanity,” is a legal term and can only be determined by the court. Decision-making capacity, though, refers to a patient's ability to make specific decisions about his health care, as determined by his clinician. Decision-making capacity is always decision relative (for a specific decision or related type of decision) rather than global (all decisions). Having decision-making capacity relates to the patient's level of understanding of that decision, which in turn is related to both the seriousness of the potential outcomes and the complexity of the information presented. Unless a patient is unconscious, he is unlikely to lack decision-making capacity for at least the simplest decisions.

To have adequate decision-making capacity in any one circumstance, individuals must understand the options, the consequences of acting on the various options, and the costs and benefits to them of these consequences in terms of their personal values and priorities ( Box 3) [19], [20]. Disagreement with the physician's recommendation is not by itself grounds for determining that the patient is incapable of making a decision. In fact, even refusing lifesaving medical care may not prove the person incapable of making valid decisions if the refusal is based on firmly held beliefs, as is sometimes the case with patients who are Jehovah's Witnesses. Using medications, such as antipsychotics, to restore decision-making capacity carries the danger of simultaneously diminishing a patient's discriminatory thought processes. Standards for determining adequate decision-making capacity in these instances is a difficult and unresolved area of emergency medicine and psychiatric practice [21].

Box 3. Components of decision-making capacity.

-

•

Knowledge of the options

-

•

Awareness of consequences of each option

-

•

Appreciation of personal costs and benefits of these consequences in relation to relatively stable values and preferences (When ascertaining this, ask the patient why they made a specific choice.)

Adapted from Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, et al, editors. Ethics in emergency medicine, 2nd edition. Tucson (AZ): Galen Press; 1995. p. 52.

If patients lack capacity to participate in some decisions about their care, surrogate decision-makers must become involved. These surrogates may be designated by the patient's advance directives or detailed in institutional policy or law. (Some countries do not recognize surrogate decision-making [22].) Surrogate decision-makers may include spouses, adult children, parents (of adults), and others, including the attending physician. On occasion, bioethics committees or the courts will need to intervene to help determine the decision maker.

Children represent a special situation. Individuals less than the age of majority (or unemancipated) are usually deemed incapable of making independent medical decisions, although they are often asked to give their assent to the decision, allowing them to “buy in” to their medical treatment plan. In those cases, the physician–parent–child relationship is triadic, with parents in the unusual position of being able to make choices based on quality of life [23]. In many cases, when deciding which children have decision-making capacity, the same rules that apply to adult capacity apply to children. The more serious the consequences, the more children are required to understand the options, consequences, and values involved.

Emergency physicians often operate within variable degrees of uncertainty, with less-than-ideal information, and under severe time constraints. Therefore, they must often quickly decide whether patients lack “decision-making capacity,” the ability to make their own health care decisions. While this is obvious in the unconscious or delirious patient, it is often less so when the patient remains verbal and at least somewhat coherent. Decisions in emergency situations must often be made rapidly and, unlike other medical venues, bioethics consultation may not be readily available.

Limitations on autonomy

Personal autonomy has limitations. Within emergency medicine, this often arises in the context of patients who are actively suicidal or homicidal. These patients, even though they may desire to leave the emergency department or to refuse treatment, cannot do so. In these cases, beneficence, for the patient and society, trumps autonomy. The same holds true with patients involved in physician-assisted suicide who present to the emergency department after an unsuccessful suicide attempt. Patients can be allowed to die (passive euthanasia) if there is sufficient time to “consider the morally relevant features of the situations, including the patient's decision-making capacity and desires, current condition and medical history, and the nature of the suicide attempt.” The luxury of time usually does not exist in these cases, so lifesaving interventions must be provided, at least until more information can be ascertained. Treatment can then be withdrawn. In no cases should emergency physicians administer lethal drugs or otherwise assist such patients to complete the suicide [24], [25].

Other bioethical principles

In addition to autonomy, other bioethical principles guide the actions of emergency clinicians. The following are short descriptions of some of these.

Beneficence

Beneficence, doing good, has long been a universal tenet of the medical profession at the patient's bedside. Most health care professionals entered their career to apply this principle. Outside typical emergency medicine practice, beneficence is the guiding principle behind Good Samaritan actions when emergency department physicians render aid after motor vehicle crashes, on airplanes, after disasters, and in other situations without expectation of recompense [26]. In emergency departments, this principle guides physician behavior in the face of epidemics carrying potential personal risk, such as was initially true with hantavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and AIDS.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is the philosophical principle that encompasses the medical student's principal rule, “First, do no harm.” This credo, often stated in the Latin form, primum non nocere, derives from knowing that patient encounters with physicians can prove harmful as well as helpful. This principle includes not doing harm, preventing harm, and removing harmful conditions. Within emergency medicine, nonmaleficence also includes the concept of security. That means protecting the emergency clinician and the clinician's team, as well as the patient, from harm [27].

Confidentiality versus privacy

Stemming at least from the time of Hippocrates, confidentiality is the presumption that what the patient tells the physician will not be revealed to any other person or institution without the patient's permission. Health care workers have an obligation to maintain patient confidentiality. Occasionally, the law, especially public health statutes that require reporting specific diseases, injuries, mechanisms, and deaths, may conflict with this principle. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, a US federal law designed to further protect patient information, has, paradoxically, made obtaining the information needed for patient care in emergency departments more difficult.

Long used in emergency departments, drug-seeker lists can be seen as violations of patient confidentiality. These lists can directly harm patients, especially when patient entry and clinician access to these lists are not properly controlled [28]. Rarely discussed, however, are similar computer lists of prior emergency department visits that can be easily generated from most emergency department computer systems.

In another recent development, part of the “reality TV” fad, emergency department activities are being filmed for public viewing. Filming emergency department patients, whether for medical records, education, peer review, or for “reality television,” strains the nature of confidentiality, since these records can easily be distributed or misused. Although good reasons exist to allow such filming with patient acquiescence [29], the standard is now to abstain from such filming for commercial purposes and to require patient or surrogate consent for educational purposes [30].

Privacy, often confused with confidentiality, is a patient's right to be afforded sufficient physical and auditory isolation so that others cannot view or hear them when interacting with medical personnel. Emergency department overcrowding, patient and staff safety, and emergency department design limit patient privacy in many cases.

The increasing use of telemedicine to render advice and eventually to guide procedures at remote sites also places a strain on both patient privacy and confidentiality. Suggested ethical guidelines for such practice can facilitate the use of these new technologies without sacrificing either patient rights or physician duties [31].

Personal integrity

Personal integrity involves adhering to one's own reasoned and defensible set of values and moral standards, and is basic to thinking and acting ethically. Integrity includes a controversial value within the medical community—truth telling. Many who feel that the patient has the right to know the truth no matter what the circumstances have championed absolute honesty. Yet, honesty does not have to be the same as brutality, and must be tempered with compassion. Perhaps truth telling is not universally accepted within the medical profession because of poor role models, lack of training in interpersonal interactions, and bad experiences, rather than a discounting of the value itself [32]. The issues surrounding truth telling become somewhat murky in cases involving a third party, such as a sex partner who is being exposed to an infectious disease [32].

Distributive justice (fairness)

Distributive justice relates to fairness in the allocation of resources and to the physician's obligations to patients. This value is the basis of and is incorporated into society-wide health care policies. The concept of comparative or distributive justice suggests that a society's comparable individuals and groups should share similarly in the society's benefits and burdens. Yet, for individual clinicians to arbitrarily limit or terminate care on a case-by-case basis at patients' bedsides is an erroneous extrapolation of the idea that there may be a need to limit health care resource expenditures [33]. Distributive justice is a policy, rather than a clinical, concept.

In emergency medical practice, the most direct application of distributive justice is in triage. Triage situations exist on a continuum, ranging from the daily triage performed in emergency departments to the absence of triage after the use of weapons of mass destruction. While utilitarian ethics are normally invoked to justify triage, it actually involves a combination of utility and strict equality, depending on patients' apparent disease or injury severity [34]. A unique aspect of triage in area-wide disasters is the priority given to health care workers, public safety personnel, and community leaders, who can be returned to duty to either help decrease morbidity and mortality or to help stabilize social order [35], [36].

Medical and moral imperatives in emergency medicine

Emergency clinicians, both in the prehospital care and emergency department environments, operate with four imperatives: (1) to save lives when possible, (2) to relieve pain and suffering, (3) to comfort patients and families, and (4) to protect staff and patients from injury. All but the last of these are also imperatives for most other clinicians, although saving lives may occur more often and more dramatically in emergency medical settings than in most other settings.

The imperative to save lives causes the most conflict between emergency and ICU clinicians. Emergency physicians know that some of the intubations and resuscitations they perform are unwanted by patients or surrogates. Nearly all emergency physicians have gotten calls from irate intensive care clinicians or private practitioners berating them for resuscitating patients “who should not have been resuscitated.” Many families have heard these physicians berate the emergency department and ambulance staffs for their over-aggressive resuscitative efforts. Yet, the lifesaving imperative begins when the ambulance is called.

Emergency medical service personnel are required to attempt resuscitations except when there is no chance that life exists (eg, decapitation, rigor mortis, charred beyond recognition, or decomposition). They usually have little leeway in whom to resuscitate. The real answer is for primary physicians to educate the families of homebound hospice-type patients to not call the ambulance (or police) when the person dies, but rather to call the clinician to pronounce the person dead.

Recently, the emergency medicine community has developed a method to avoid medical interventions, even when the ambulance is inadvertently called. Prehospital advance directives, which are made by patients or surrogates, and prehospital do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders, which are issued by physicians, have proved very successful where they have been implemented [37], [38]. The orders usually specify that intubation, artificial ventilations, cardioversion, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation should not be performed on an individual. Some focus on providing comfort care, even if life-support measures are declined [39]. Arizona is the only state that allows the use of prehospital advance directives and prehospital do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders for children [40].

The last imperative, safety, is nearly unique to emergency medical clinicians. Both in the prehospital and emergency department settings, clinicians often encounter dangerous situations, be they from the environment (eg, fires, extreme cold, floods), patients, or families. While most clinicians try to accommodate “patient rights,” their priorities must be their own safety and the safety of their coworkers when safety questions arise. That does not imply that clinicians should ignore patient safety, but only that they should first ensure their own safety if they and their colleagues are at risk (often from the patient).

Ethical oaths and codes

Through the years, the medical profession has codified its ethics more rigorously than any other professional group, incorporating many standard bioethics principles into the profession's ethical codes and oaths. For generations, the existing part of the Hippocratic Oath set the ethical standard for the medical profession ( Box 4). Yet, its precepts clash with modern bioethical thinking, and many subsequent professional codes have included what may best be termed economic guidelines and professional etiquette along with ethical precepts [41].

Box 4. Hippocratic Oath.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and by Health [the god Hygiea] and Panacea and all the gods as well as goddesses, making them judges [witnesses], to bring the following oath and written covenant to fulfillment, in accordance with my power and my judgment;

to regard him who has taught me this techné [art and science] as equal to my parents, and to share when he is in need of necessities, and to judge the offspring [coming] from him equal to [my] male siblings, and to teach them this techné, would they desire to learn [it], without fee and written covenant,

and to give a share both of rules and of lectures, and of all the rest of learning, to my sons and to the [sons] of him who has taught me and to the pupils who have both made a written contract and sworn by a medical convention but by no other.

And I will use regimens for the benefit of the ill in accordance with my ability and my judgment, but from [what is] to their harm or injustice I will keep [them].

And I will not give a drug that is deadly to anyone if asked [for it], nor will I suggest the way to such a counsel.

And likewise I will not give a woman a destructive pessary.

And in a pure and holy way I will guard my life and my techné.

I will not cut, and certainly not those suffering from stone, but I will cede [this] to men [who are] practitioners of this activity.

Into as many houses as I may enter, I will go for the benefit of the ill, while being far from all voluntary and destructive injustice, especially from sexual acts both upon women's bodies and upon men's, both of the free and of the slaves.

And about whatever I may see or hear in the treatment, or even without treatment in the life of human beings—things that should not ever be blurted out outside—I will remain silent, holding such things to be unutterable [sacred, not to be divulged].

If I render this oath fulfilled, and if I do not blur and confound it [making it to no effect] may it be [granted] to me to enjoy the benefits both of life and of techné, being held in good repute among all human beings for time eternal. If, however, I transgress and perjure myself, the opposite of these.

From von Staden H. “In a pure and holy way”: personal and professional conduct in the Hippocratic Oath. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1996;51:406–8; with permission.

Many current medical ethical codes have been criticized for being more professional management guidelines than ethical codes. Bioethics and professional etiquette are two distinct bodies of values and standards. Bioethics deals with relationships between practitioners and patients, practitioners and society, and society and patients. Professional etiquette relates to standards governing the relationships and interactions among practitioners. Although the two areas occasionally overlap, they rely upon different standards, different values, and different methods of solving problems.

Most modern ethical codes prescribe only the same basic moral behavior for members to follow that is expected by the society at large, and do not require any higher level of duty or commitment. In fact, many of the ethical issues that would seem important to medical specialties are usually not addressed in their codes. Even when topics of interprofessional interactions are excluded, existing medical professional codes differ markedly ( Table 2). All, however, try to give a “bottom line” course of action below which the medical practitioner may not pass.

Table 2.

Comparison of six ethical codes

| SAEM | ACEP | EMRA | AMAa | AOAb | Hippocratic Oath | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protect patient confidentiality | c | X | X | X | X | X |

| Maintain professional expertise | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Committed to serve humanity | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Patient welfare primary concern | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Considerate to patients, colleagues | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Respect human dignity | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Safeguard public health | X | X | X | X | ||

| Protect vulnerable | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Advance professional ideals | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Honesty | d | X | X | X | ||

| Report incompetent, dishonest, impaired physicians | d | X | X | X | ||

| Moral sensitivity | X | X | X | |||

| Obtain necessary consultation | X | X | X | |||

| Altruism in teaching | X | X | X | |||

| Fairness to students, colleagues | X | X | X | |||

| Obey, respect the law | X | X | X | |||

| Prudent resource use | X | X | ||||

| Work to change laws for patient benefit | X | X | ||||

| Not abuse privileges | X | X | ||||

| Respect for students | X | X | ||||

| Choose whom to serve except in emergencies | X | X | ||||

| Ensure beneficial research with competence, impartiality, compassion | X | |||||

| No abortion | X | |||||

| No euthanasia | X | |||||

| Do not compromise clinical judgment for money | X | |||||

| Universal access to healthcare | X | |||||

| Preserve human life | X |

The American Association of Emergency Medicine's ethical code deals primarily with questions of professional etiquette, including conflicts of interest. The American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians do not have an ethical oath or code.

Abbreviations: ACEP, American College of Emergency Physicians; AOA, American Osteopathic Association; AMA, American Medical Association; EMRA, Emergency Medicine Residents's Association; SAEM, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The American Medical Association has both a relatively brief Principles of Medical Ethics (nine points) and an extensive Code of Medical Ethics.

The American Osteopathic Association has both a Code of Ethics and an interpretation of some of its sections.

The SAEM code addresses research subject privacy, but not confidentiality—an unusual oversight.

The SAEM code deals primarily with research when addressing these issues.

In the spirit of returning to basic bioethical principles, the American College of Emergency Physicians ( Box 5), the Emergency Medicine Residency Association ( Box 6), and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (see Box 2) have adopted patient-focused bioethical codes. In 2001, the American Medical Association also revised its Ethical Principles.

Box 5. American College of Emergency Physicians principles of ethics for emergency physicians.

The principles section of the Code of Ethics for Emergency Physicians, the first of three sections in the code, lists 10 ethics guidelines for emergency physicians to follow in their emergency medicine practice. The following is the principles section only:

The basic professional obligation of beneficent service to humanity is expressed in various physician oaths. In addition to this general obligation, emergency physicians assume more specific ethical obligations that arise out of the special features of emergency medical practice. The principles listed below express fundamental moral responsibilities of emergency physicians.

Emergency physicians shall:

-

1.

Embrace patient welfare as their primary professional responsibility.

-

2.

Respond promptly and expertly, without prejudice or partiality, to the need for emergency medical care.

-

3.

Respect the rights and strive to protect the best interests of their patients, particularly the most vulnerable and those unable to make treatment choices due to diminished decision-making capacity.

-

4.

Communicate truthfully with patients and secure their informed consent for treatment, unless the urgency of the patient's condition demands an immediate response.

-

5.

Respect patient privacy and disclose confidential information only with consent of the patient or when required by an overriding duty such as the duty to protect others or to obey the law.

-

6.

Deal fairly and honestly with colleagues and take appropriate action to protect patients from health care providers who are impaired, incompetent, or who engage in fraud or deception.

-

7.

Work cooperatively with others who care for, and about, emergency patients.

-

8.

Engage in continuing study to maintain the knowledge and skills necessary to provide high quality care for emergency patients.

-

9.

Act as responsible stewards of the health care resources entrusted to them.

-

10.

Support societal efforts to improve public health and safety, reduce the effects of injury and illness, and secure access to emergency and other basic health care for all.

From American College of Emergency Physicians. Code of ethics for emergency physicians. Dallas (TX): American College of Emergency Physicians; 1997; with permission.

Box 6. Emergency Medicine Residents' Association code of ethics.

Emergency Medicine Residents' Association Principles of Medical Ethics preamble

These principles are intended to aid physicians individually and collectively in maintaining a high level of ethical conduct. They are not laws, but standards by which a resident physician may determine the propriety of his conduct in his relationship with patients, with colleagues, with members of allied professions, and with the public.

-

1.

The principal objective of the medical profession is to render service to humanity with full respect to the dignity of man. Physicians should merit the confidence of patients entrusted to their care, rendering the full measure of service and devotion.

-

2.

Physicians should strive continually to improve medical knowledge and skill, and should make available to their patients and colleagues the benefits of their professional attainments.

-

3.

The medical profession should safeguard the public and itself against physicians deficient in moral character or professional competence. Physicians should observe all laws, uphold the dignity and honor of the profession, and accept its self-imposed disciplines. They should expose, without hesitation, illegal or unethical conduct of fellow members of the profession.

-

4.

A physician should not dispose of his services under terms and conditions that tend to interfere with or impair the free and complete exercise of his/her judgment and skill, or tend to cause a deterioration of the quality of medical care.

-

5.

A physician may not reveal the confidences entrusted to him in the course of medical attendance, or the deficiencies he may observe in the character of patients, unless he is required to do so by law or unless it becomes necessary to protect the welfare of the individual or of the community.

-

6.

The honored ideals of the medical profession imply that the responsibilities of the physician extend not only to the individual but also to the society where these responsibilities deserve his interest and participation in activities that have the purpose of improving both the health and well-being of the individual and the community.

From Article VIII, Emergency Medicine Residents' Association Bylaws, Dallas, TX: EMRA, 2003; with permission.

Applying bioethics

Moral reasoning, used in bioethics, is one of the three basic reasoning strategies (ie, moral, deductive, and inductive) [42]. Yet, to apply bioethical principles to a clinical situation, one first must recognize that a bioethical problem exists. To do this, practitioners must read and discuss the issues and specific situations both to be able to recognize bioethical issues within clinical cases and to formulate plans for dealing with them.

Although physicians like to reduce all clinical situations to “medical problems,” today's complex medical environment often produces problems that are inexorably intertwined with fundamental bioethical dilemmas. Some are obvious, but many are more difficult to recognize. The key to recognizing bioethical issues and applying ethical principles and virtuous behavior is preparation for both their obvious and their subtler presentations. In the same way that physicians must prepare for other critical events encountered in medicine, physicians must read, discuss, and think about how to face these issues when they present. This strategy leads not only to personal preparation, but also to more general policies that help guide everyone faced with difficult bioethical issues.

Prioritizing principles: the bioethical dilemma

In the abstract, bioethical principles often appear simple. However, clinicians usually adhere not only to basic bioethical principles, but also, at least tacitly, to ethical oaths, codes, and statements of a number of professional, religious, and social organizations. This can make for a confusing array of potentially conflicting bioethical imperatives. Since bioethical principles seem to be neither universal nor universally applied, those principles that are most patient-centered normally hold sway.

Even then, applying bioethical principles in practice can be confusing. When two or more seemingly equivalent principles or values seem to compel different actions, a bioethical dilemma exists. This situation is often described as “being damned if you do and damned if you don't,” where taking any course of action or taking no action at all could potentially result in harm of one kind or another. In the following actual case, the attending physician can be said to be on the horns (two prickly but seemingly equal choices) of a dilemma. The physician seems to have only two options for action and they both involve a number of conflicting bioethical principles.

Case

The emergency medical service transported a 43-year-old woman to the emergency department after a bus struck her. Although tachycardic and in obvious pain from pelvic and leg injuries, she was awake, alert, and fully responsive to all questions. Her abdomen was rapidly distending with a large amount of intraperitoneal fluid on a focused-assessment-with-sonography-in-trauma (FAST) exam. As the operating room was being readied, a surgery resident asked the patient to consent for the blood transfusions she would need to survive. She refused, saying, “I am a Jehovah's Witness and will not take blood or blood products.” The resident instructed that the blood be sent back to the blood bank.

The emergency physician then approached the patient and asked her what she had been told. She lucidly explained that she was simply told that she “needs blood before surgery.” She agreed to surgery, but declined the blood. When asked whether she had been told that she would die within the half hour, she asked if all other options had been tried. When told that they had—saline had been administered and a cell saver outside the operating room was not an option—she simply said, “Well, I don't want to die; give me the blood.” As it turned out, the 30-minute estimate was too generous; with her injuries, she would have died sooner. If, with the demonstrated decision-making capacity for this decision, she had still opted not to receive blood, it would have been withheld.

The patient immediately began receiving blood and went to the operating room. She eventually received dozens of units of blood and fresh frozen plasma, but survived her injuries in a fully functional condition.

Case discussion

This patient demonstrated decision-making capacity, including knowledge of the options presented, understanding of the risks and benefits to her of the options, and the ability to state how her choices—first one, then the other—meshed with her stable values. The problem, of course, is that “informed consent” must include the information necessary to make a reasoned decision. As in all parts of medicine, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. In this case, the resident had learned a little about patient autonomy, but had inadequate knowledge about giving informed consent, which almost cost this patient her life. Nevertheless, these actions fell within a morally acceptable range: They passed the Impartiality Test, Universalizability Test, and Interpersonal Justifiability Test, described below.

Clinical practice

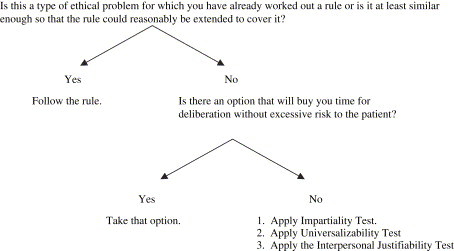

Emergency clinicians often must make ethical decisions with little time for reflection or consultation. While bioethics committees now have an increasing ability to give at least limited “stat” consultations, even these often do not meet the need for a rapid response. For that reason, the author developed a rapid decision-making model for emergency clinicians, based on accepted biomedical theories and techniques ( Fig. 1). On occasion, this model may also be applicable to those working in critical care.

Fig. 1.

Rapid decision-making model. (From Iserson KV. An approach to ethical problems in emergency medicine. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors. Ethics in Emergency Medicine, 2nd Edition. Tuscon, AZ: Galen Press, Ltd. p. 45; with permission.)

The following rules of thumb give the emergency medicine practitioner a process to use for emergency ethical decision-making even in cases where there is not time to go through a detailed, systematic process of ethical deliberation. While somewhat oversimplified, this approach offers guidance to those who are under severe time pressures and who wish to make ethically appropriate decisions.

When using this approach, one must first ask: Is this an instance of a type of ethical problem for which I have already worked out a rule? Or, is it similar enough to such cases that the rule could be reasonably extended to cover it? In other words, if there had been time in the past to think coolly about the issues, discuss them with colleagues, and develop some rough guidelines, can the rules worked out at that time be used in this case? If the current case fits under one of those guidelines that you have arrived at through critical reflection, and you do not have time to analyze the situation any further, then the most reasonable step would be to follow that rule. In ethics, this step follows from casuistry, or case-based learning.

Such predetermined rules, of course, must be periodically evaluated. Practitioners must question whether the results obtained when they follow this rule remain appropriate. Are they compatible with the intention of the rule and with the values that underlie it? This reevaluation only emphasizes that it is unrealistic and ethically irresponsible to believe that one can work out ethical rules to be mechanically applied during an entire professional career. Similarly, it would be unrealistic and irresponsible to continue to perform a medical procedure just as one learned it in medical school, regardless of its efficacy or whether better techniques had been subsequently developed.

But, suppose that the practitioner faces an emergency case that does not fit under any previously generated ethical rule. At this point, the practitioner should ask herself if there is an option that will buy her time for deliberation. If there is such a strategy, and it does not involve unacceptable risks to the patient, then it would be the reasonable course to take. Using a delaying tactic may provide time to consult with other professionals, including the bioethics committee and the family, before developing an ethically appropriate course of action.

If there is no delaying tactic that can be used without unreasonable risk to the patient, then a set of three tests can be applied to possible courses of action to help make a decision. These are often what people use instinctively when confronted with ethical issues, whether medical or otherwise. The three tests, the Impartiality Test, the Universalizability Test, and the Interpersonal Justifiability Test, are drawn from three different philosophical theories.

Impartiality Test. Would you be willing to have this action performed if you were in the patient's place? This is, in essence, a version of the Golden Rule and is intended to correct one obvious source of moral error—partiality, or self-interested bias.

Universalizability Test. Would you be comfortable if all clinicians with the same background and in the same circumstances act as you are proposing to do? This generalizes the action and asks whether developing a universal rule for the contemplated behavior is reasonable—an application of Kant's categorical imperative. The usefulness of this test is that it can help eliminate not only bias and partiality, but also shortsightedness. Justifying one particular instance that falls under a rule is not sufficient for justifying the practice of acting on that rule.

Interpersonal Justifiability Test. Using a theory of consensus values as a final screen for the proposed action, this test asks you to provide good reasons to justify your actions to others [43]. Will peers, superiors, or the public be satisfied with the answers? Also, can you give reasons that you would be willing to state publicly?

When ethical situations arise that allow no time for further deliberation, it is probably best to act on the rule or perform the action that allows all three tests to be answered in the affirmative with some degree of confidence. Once the crisis has subsided, however, the practitioner should review the decision with the aid of colleagues and bioethicists to refine his emergency ethical decision-making abilities. In particular, it is crucial to ask whether the decision-making process has served the most basic ethical values. Were the actions taken in the emergency situation consonant with showing the kind of respect for patient autonomy that you believe appropriate? Were the ethical decisions really in the patient's best interest, or were you unduly influenced by the interests of others or considerations of your convenience or psychological comfort? Were people treated fairly, justly, and equitably?

Ethical problems, like emergency clinical problems, require action for resolution. Ideally, one would have extensive discussions and reflect in advance of each ethical decision. Discussions and reflection, of course, are not possible for many emergency care decisions. Nevertheless, by making a sincere effort to anticipate recurring types of problems, subjecting them to ethical analysis in advance, and conscientiously reviewing decisions after they have been made, the emergency care professional can better fulfill his or her ethical responsibilities. That a decision is an emergency decision, therefore, does not remove it from the realm of ethical evaluation.

What is the difference between withholding and withdrawing treatment?

As the ambulance screams to a halt and the medics bring in a patient in critical condition, only rarely will emergency physicians have enough information to make a judgment that intervention would be futile (see next section). They usually lack vital information about their patients' identities, medical conditions, and wishes. Therefore, they must intervene quickly to try to save a life [44], [45]. Only later, when relatives arrive or medical records become available, may they discover that the patient has a terminal disease or near death, did not want resuscitative efforts, or even has excruciating pain and was wishing for death. Yet, due to the limited information available when the patient arrives in the emergency department, the emergency physician's mandate to attempt resuscitation is morally justifiable.

Ethicists usually do not distinguish between withholding treatment and withdrawing treatment (through an act of omission) [46]. Yet, in emergency medicine, the difference between withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining medical treatment is significant. The justification for this difference stems, in part, from the nature of emergency medical practice and the unique manner in which clinicians apply many ethical principles. While a clear moral distinction between withholding and withdrawing treatment may be absent from other medical areas, emergency medical care's unique circumstances continue to make this distinction relevant and morally significant.

In the usual medical setting, withholding further medical treatment is done quietly, often without input from the patient or surrogate decision-maker, while withdrawing ongoing medical treatment can be more obvious and difficult. This situation is reversed in the emergency medical setting. Withholding emergency medical treatment is much more problematic than withdrawing unwanted or useless interventions later. Society has specific expectations of emergency medical practitioners. Due to the nature of emergency medicine, both in the prehospital and the emergency department settings, the distinction between withdrawing and withholding medical treatment has never disappeared and is not likely to disappear in the future [45].

While lifesaving medical interventions may not be appropriate in all cases, emergency clinicians, whenever possible, should provide patients with palliative care. The purpose of palliative interventions is not to prolong the dying process, but rather, when death is inevitable, to make it as comfortable for the patient as possible. As the Steinberg Report notes, terminal patients have the right to receive state-of-the-art palliative care [47]. Palliation often includes analgesics, and may include diuretics, sedation, oxygen, paracentesis or thoracentesis, or other medications or procedures to alleviate suffering. While medical personnel may withdraw or withhold treatment, they should never withdraw or withhold care. While medical practitioners, surrogate decision-makers, and sometimes patients find it emotionally easier to forego new interventions than to withdraw ongoing treatment, no orders, policies, or directives should ever prevent emergency physicians from caring for their patient (ie, alleviating discomfort). As patient advocates, emergency physicians may need to “push” to have the patient admitted to a hospital, hospice, or nursing home, or to get ancillary personnel (eg, social workers, home health nurses) to intervene for the patient.

Is futility an issue in emergency care?

Emergency physicians, nurses, and emergency medical system personnel may, in some circumstances, feel that further medical interventions are futile. This commonly used but still controversial concept has been described as a judgment about “odds and ends.” That is, efforts with very low odds of achieving desired ends [48]. Some have suggested replacing the nebulous term “futility” with seemingly more specific adjectives for medical interventions, such as “nonbeneficial,” “ineffective,” “medically inappropriate,” or “with a low probability of success” [49]. Yet, for now, “futility” remains a common part of the medical vernacular, and so should be discussed in that way.

Only three circumstances meet the most commonly accepted definition of futility [50]. The first, which clinicians can only identify in a very limited set of circumstances, is when the intervention is effective in <1% of identical cases, based on the medical literature. Emergency department thoracotomies for blunt trauma are just such a circumstance. However, individual clinician's experiences cannot be relied upon, since they are often skewed due to selective memory, limited numbers of similar cases, and other biases. A common scenario with survival rates approaching 0% is the out-of-hospital cardiac arrest that is not witnessed or arrives from a long-term care facility [51].

The second futile circumstance is physiological futility, when known anatomical or biochemical abnormalities will not permit successful medical interventions. Examples generally accepted by emergency medical systems as reasons not to intervene or provide transport to hospitals include rigor mortis, algor mortis, patients burned beyond recognition, or injuries incompatible with life (eg, decapitation). These, along with prolonged normothermic resuscitative attempts without success, prolonged “down time” with an isoelectric ECG, or pulseless electrical activity are the criteria often used to help determine whether emergency medical personnel can pronounce death on the scene. Emergency medical services, in these instances, need not expend valuable resources in a futile resuscitative effort.

The third category, based on the patient's values, when known, is that intervention will not achieve the patient's goals for medical therapy. Since this course is based on knowing the patient's values related to medical treatment, it is necessary to have talked with the patient in advance, which is rare in the emergency department setting; to have received surrogate-supplied information or decisions; or to have access to the medical record. The danger is that differences in values between caregivers and patients may lead to over- or under-treatment. Communication, if necessary using a third party, may help resolve these issues.

A fourth futility category, qualitative futility, has been discussed, but is only applicable when based on the patient's values. A case of qualitative futility is that where medical interventions will not lead to an acceptable quality of life [52]. Recognizing that, the American College of Emergency Physicians assert, “Physicians are under no ethical obligation to render treatments that they judge have no realistic likelihood of medical benefit to the patient” [53].

The futility concept, however, should not be used to deny care to dying patients. Even terminal patients have medical emergencies that require intervention. The goal is to ease pain and suffering. How that is accomplished depends upon the patient, the medical condition causing discomfort, and the patient's value system.

Bioethics committees and consultants

In most large hospitals, multidisciplinary bioethics committees have been established to help resolve bioethical dilemmas. Meanwhile, many smaller hospitals now have bioethics consultants. Not only do committees and consultants review bioethical dilemmas, they also act to reconfirm prognoses and to mediate between dissenting parties. The four roles that bioethics committees should perform are (1) concurrent case reviews (consultations), (2) retrospective case reviews, (3) policy development, and (4) education [54]. Not all committees are capable of performing all of these tasks. Some, however, are able to provide “stat” consultations for emergency medicine practitioners.

Education

Trainees constitute a group vulnerable to abuses. The educational milieu creates the opportunity for tension and conflict, since trainees will not possess the knowledge, skills, or experience to function smoothly in the clinical arena. Due to the imbalance in power and authority between them and their instructors, trainees may be subject to exploitation, harassment (sexual and otherwise), and pressures to act unprofessionally [55], [56], [57]. The basic principle of respect for persons applies to trainees as well as to patients and research subjects.

One area in which ethical rules are too often overlooked is that involving advice to medical students on choosing a specialty and the subsequent residency application and interviewing processes. In emergency medicine, as in all other specialties, egos often overwhelm clinicians' duty to sensitively and honestly counsel medical students about their future careers. Residency programs in relatively undersubscribed specialties also bend rules to attract residents [58].

Trainees also have a basic ethical duty: to avoid dishonesty in their nonclinical education and when working with patients. The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine cites six ethical principles for educators to follow (see Box 2) and the American College of Emergency Physicians promotes ethical guidelines for education in its Code of Ethics [59]. The Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors specifically identifies the need for education to avoid potential “conflicts of interest that may arise from the promotion and marketing efforts of industry, primarily the pharmaceutical industry” [60].

Research

Basic bioethical research principles stem from the same sources as do clinical bioethics. The primary principle is respect for persons as individuals. While seemingly obvious, the principles have been reiterated numerous times over the past 50 years, beginning with the Nuremberg Code and finding clearer expression in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions [61], [62]. In the research arena, good ethical conduct also means good science, since it is morally repugnant to subject patients to discomfort, not to mention risk, if the results of a study will be meaningless.

Many countries have established special review boards to oversee research protocols. However, some have called into question the performance of these review boards [62a]. Ethical constraints also surround the publication of research, with ethical guidelines now in place covering such topics as data falsification, redundant publications, requirements for patient informed consent, plagiarism, requirements for authorship, and unethical research [63]. The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine cites six ethical principles for researchers to follow (see Box 2) and the American College of Emergency Physicians promotes ethical guidelines in its Code of Ethics [59].

A well-recognized ethical problem for research related to emergency medicine and critical care has been the inability to get informed consent for many studies involving emergent interventions in patients with medical crises and diminished consciousness. A revised Declaration of Helsinki permits such research using surrogate decision-makers and increased institutional review board review [64]. In the United States, federal rules now permit waivers for informed consent in these situations if the institutional review board first does an intensive assessment, including community consultation meetings. This last requirement has proven troublesome, since it has not been well defined or previously used. Researchers have now developed models for successfully identifying, organizing, and using these groups [65], [66], [67].

Proactive bioethics

What are proactive ethics? How can emergency physicians change the rules?