Abstract

In this study methods for the quantification of baicalin and total baicalein in Scutellariae radix with near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy and attenuated-total-reflectance mid-infrared (ATR-IR) spectroscopy in hyphenation with multivariate analysis were developed and compared. The reference analysis was performed by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to diode array detection (HPLC-DAD). Different pretreatments like standard normal variate (SNV), multiplicative scatter correction (MSC), first and second derivative Savitzky-Golay were applied on the spectra to optimize the calibrations. A principal component analysis was performed with both spectroscopic methods to distinguish wild and cultivated samples. Quality parameters obtained for test-set calibration models of ATR-IR spectroscopy (baicalin: standard error of prediction (SEP)=1.31, ratio performance to deviation (RPD)=2.91 and R2=0.88; total baicalein: SEP=1.02, RPD=3.24 and R2=0.89) and NIR spectroscopy (baicalin: SEP=1.50, RPD=2.54 and R2=0.88; total baicalein: SEP=1.19, RPD=2.76 and R2=0.84) demonstrate that both spectroscopic techniques in combination with multivariate analysis are successful tools for the quantification of baicalin and total baicalein in Scutellariae radix, but it was found that ATR-IR spectroscopy provides higher accuracy in the given application. Furthermore it was proved that wild and cultivated samples can be distinguished by ATR-IR.

Keywords: Scutellaria baicalensis, Scutellariae radix, Baicalin, Baicalein, ATR-IR, NIR

Highlights

-

•

ATR-IR and NIR spectroscopic methods were developed and compared.

-

•

Baicalin and total baicalein were determined in Scutellaria baicalensis.

-

•

ATR-IR and NIR spectroscopy are suitable to determine the baicalin and total baicalein content.

-

•

ATR-IR reveals better quality parameters than NIR spectroscopy.

-

•

Cultivated and wild-type samples could be distinguished by PCA analysis of ATR-IR spectra.

1. Introduction

Scutellariae radix (root of Scutellaria baicalensis), also known as Huang-Qin, is of high pharmacological interest due to the contained flavonoids. There are many species of plants used by traditional Chinese medicine and the various quality of plants depends on the species, conditions and growth sites, the harvest season and the time of storage [1].

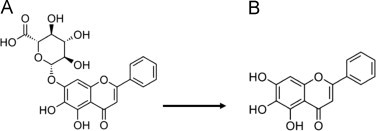

About 30 flavonoids in Scutellariae radix [2] were analysed by different analytical techniques such as capillary electrophoresis [3], [4], gas chromatography [5], thin layer chromatography (TLC) [5], [6], ion-pair (IP) high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [7], reversed phase HPLC [8], [9], HPLC coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) [10] and high speed counter current chromatography (HSCCC) [11]. The main flavonoids contained in the plant are baicalin, baicalein and wogonin with a decreasing content in the mentioned order. Chemical structures of baicalin and baicalein are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of baicalin (A) and baicalein (B).

In various scientific publications the investigations of several pharmacological effects of baicalin and its aglycone baicalein were presented. Both compounds show anti-tumor effects [12], [13] and inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells or induce apoptosis in breast and prostatic cell lines [14], [15], [16]. Furthermore anti-inflammatory [17], antioxidant and free radical scavenging [18], [19] effects were reported. Additionally, anti-viral effects against HIV [20], [21] and the SARS coronavirus [22] could be observed. Due to the intense industrial phytopharmaceutical use of baicalin and baicalein, it is very important to have a fast and robust tool for the quality control of Scutellariae radix.

Therefore, near infrared (NIR) and attenuated-total-reflectance infrared (ATR-IR) spectroscopic methods for qualitative and quantitative analysis of baicalin and total baicalein content in Scutellariae radix were developed. These methods present a number of advantages over the above mentioned conventional methods. ATR-IR and NIR spectroscopy does not require the use of reactants and almost no sample preparation. The analysis time is relatively short and the techniques are non-destructive.

In recent years, ATR-IR was investigated for its use in pharmaceutical [23], textile [24], food [25], [26], [27], [28], wine [29], [30] and olive oil [31] industry. NIR spectroscopic methods have been developed in combination with multivariate data analysis for fruit [32], [33], coffee [34], plant [35], [36] and pharmaceutical [37] applications. Both methods demonstrated their suitability for many applications, but just a few comparative studies can be found in the literature. ATR-IR has disadvantages for inhomogeneous samples because of the low penetration depth and the small scanning area [36]. To overcome this problem, the samples were milled and homogenized to obtain comparable results.

The two objectives pursued in this research are the quantitative analysis of baicalin and total baicalein in Scutellariae radix and to establish spectroscopic methods to distinguish Chinese cultivated and wild-type samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples and sample preparation

22 wild-type and 27 cultivated samples were collected from different geographical origins in China (see Table 1) from August to September. Cultivated samples are originating from Hebei province.

Table 1.

Number of Scutellariae radix samples collected from different regions in China.

| Wild samples |

Cultivated samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Origin | Quantity | Origin |

| 4 | Inner Mongolia province (IM) | 3 | Inner Mongolia province (IM) |

| 3 | Shanxi province1 (SX1) | 3 | Shanxi province1 (SX1) |

| 2 | Shanxi province2 (SX2) | 1 | Shanxi province2 (SX2) |

| 4 | Heilongjiang province (HLJ) | 1 | Henan province (HN) |

| 1 | Shandong province (SD) | 6 | Shandong province (SD) |

| 1 | Beijing (BJ) | 1 | Beijing (BJ) |

| 4 | Hebei province (HB) | 8 | Hebei province (HB) |

| 2 | Jilin province (JL) | 2 | Jilin province (HB) |

| 1 | Gansu province (GS) | 1 | Gansu province (GS) |

| 1 | Liaoning province (LN) | ||

The samples were air-dried, broken into small pieces with scissors and converted into a powder by using a grinder. Every sample was mixed with a spatula to obtain homogeneous powders. Then the samples were weighed and dried to a constant weight at 105 °C to determine the content of water and to remove the water. Finally, the powders were sieved using a 100-mesh (150 μm) sieve and stored in air-tight containers before analysis.

2.2. Reagents

Baicalin and baicalein (≥95%) were provided by the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, China). Formic acid (FA), methanol and ethanol (all analytical grade) were procured from Beijing Chemical Reagent Company (Beijing, China). Acetonitrile (ACN) HPLC-grade was purchased from Fisher-Scientific (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, USA). Double deionized water and distilled water was prepared using a Milli-Q-water-purification system (Millipore, Molsheim, France).

2.3. HPLC-DAD

0.1 g of Scutellariae radix powder was suspended in 20 ml ethanol/water (7/3, v/v) and remained in an ultrasonic bath for 60 min. After this procedure the extract was adjusted to 20 ml using the ethanol/water mixture. Then, the suspension was filtered through quantitative filter paper followed by a filtration with a 0.45 μm syringe filter (Agela, Newark, USA). HPLC analysis were performed on a Waters Alliance HPLC system (Waters, Milford, USA), equipped with a quaternary solvent deliver system, an auto-sampler and a DAD system. A Diamonsil ODS column (Dikma, Richmond Hill, USA) (250 mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size) was deployed as stationary phase. Injection volume was 6 μl, the temperature was set to 30 °C and the detection wavelength was 280 nm. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Solvent A was ACN/water/FA (21/78/1, v/v/v) and solvent B was ACN/water/FA (80/19/1, v/v/v). Following gradient was performed: 0 min, 0% B; 10 min 0% B; 35 min, 10% B; 70 min, 35% B; 70 min, 95% B and 100 min 95% B. The system was re-equilibrated for 20 min with 0% B before the next injection [38]. Samples were measured in triplicates. The intra-day and inter-day variability were examined by five replicated injections in two consecutive days for both flavonoids. The limit of detection (LOD) was obtained at a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of three and the limit of quantification (LOQ) at a S/N ratio of ten. Total baicalin content was calculated as the sum of measured baicalein and the amount baicalein contained in baicalin after theoretical hydrolysis (see Fig. 1).

2.4. ATR-IR spectroscopy

All spectra were obtained with a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 ATR-IR spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, USA) and a Spectrum software version 6.3.1 (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, USA). The measured wavenumber range was 4000–650 cm−1. Every sample was divided into three subsamples and every subsample was measured with 100 scans. The spectral resolution was 1 cm−1 and temperature was set to 22 °C.

2.5. NIR spectroscopy

Spectra were recorded with a Büchi NIR Flex-N500 spectrometer (Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland) equipped with a solid sample module. Samples were measured three times with 100 scans on a rotating cylinder device. The powder in the sample cup was shaken between the measurements. Spectral resolution was 8 cm−1 and the wavenumber range was 10000–4000 cm−1.

Furthermore, the measurements were acquired at 22 °C.

2.6. Multivariate analysis

All pre-treatments and calculations were performed using the Unscrambler X 10.0.1 software (Camo, Oslo, Norway). First, the spectra were transformed log 1/R and the three spectra of each sample were averaged. Then, standard normal variate (SNV), [39] multiplicative scatter correction (MSC) [40], first or second derivative Savitzky-Golay [41] was applied prior to PLS regression. Furthermore, combinations of the pre-treatments were tested to achieve better calibrations. The best number of smoothing points for the derivatives was evaluated and is given in brackets (e.g. first derivative (13)). For both spectroscopic methods cross validation and test-set validation models were performed. Cross validation was calculated as leave-one-out full cross validation. The selection of the best calibration model is based on following quality parameters:

-

1)Standard error of prediction (SEP)

(1) -

2)Correlation coefficient (R 2)

(2) -

3)Ratio of performance to deviation (RPD)

(3)

whereby SD is the standard deviation of the reference values used in the validation set.

The best model was chosen according to a high R 2 and RPD, a low number of factors and a low SEP (SECV). According to Williams et al., the PLS model is acceptable if the RPD is higher than 2.5 [42]. For the test-set validation of ATR-IR spectroscopy, the spectra of the samples were divided into two subsets, a calibration set with 30 samples and a validation set with 15 samples. Four outliers were removed. From the spectra-set obtained from NIR, 31 spectra were chosen for the calibration and 15 were used for the validation set. Three outliers were excluded.

For qualitative analysis of the samples a PCA was performed. The spectra were pre-treated with first derivative (15) followed by SNV. Wavenumber range used for analysis was 2996–2808 cm−1 and 1838–650 cm−1.

2.7. Intra-day and inter-day precision of ATR-IR and NIR

A sample was measured five times a day in triplicates during five days. After prediction with the best PLS models, the relative standard deviations of predicted values of one day (intra-day precisions) and all days (inter-day precisions) were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Determination of water-content in the samples

For the Chinese cultivated (wild-type) samples water contents from 7.86% to 16.14% (8.62% to 11.18%) could be found.

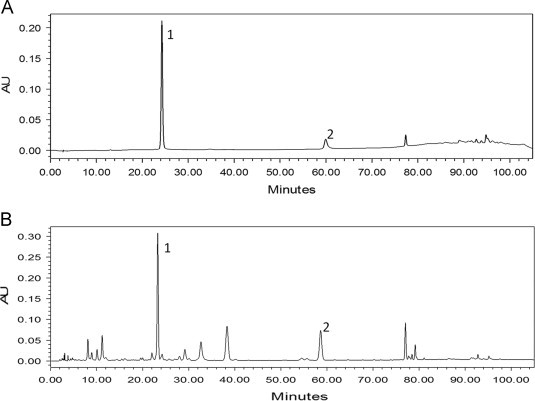

3.2. HPLC-DAD

The retention time of baicalin and baicalein in radix Scutellariae extract were 24.30 min and 60.41 min, respectively. The chromatograms of baicalin and baicalein standards and of the Scutellariae radix extract are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

(A) Chromatograms of baicalin (peak 1) and baicalein (peak 2) standard compounds. Fig. 2 (B) Chromatogram of Scutellariae radix extract obtained from the cultivated sample grown in Beijing region, peak 1: baicalin (tR=24.30 min) and peak 2: baicalein (tR=60.41 min).

The regression equations, correlation coefficients, limits of detection (LODs) and limits of quantification (LOQs) are shown in Table 2. Intra-day and inter-day variabilities are depicted in Table 3.

Table 2.

HPLC-results: Regression equation (X=concentration (μg/mL), Y=peak area), correlation coefficient (r2), limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ) and recovery of baicalin and baicalein.

| Regression equation | r2 | LOD (ng) | LOQ (ng) | Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baicalin | Y=5.27×107X−1.49×106 | 0.999 | 2.87 | 9.58 | 101.5 |

| Baicalein | Y=3.27×107X−2.77×106 | 0.999 | 3.75 | 12.5 | 102.7 |

Table 3.

Intra-day and inter-day variability of baicalin and total baicalein determined for NIR, ATR-IR and HPLC-DAD.

| Inter-day variability (%) |

Intra-day variability (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATR-IR | NIR | HPLC | ATR-IR | NIR | HPLC | |

| Baicalin | 2.66 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 2.52 | 2.28 | 0.20 |

| Total baicalein | 2.40 | 4.76 | 0.85 | 1.58 | 1.97 | 0.33 |

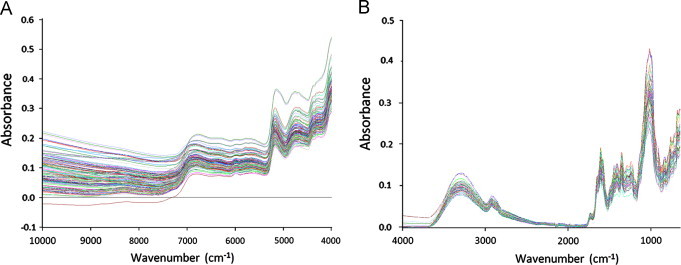

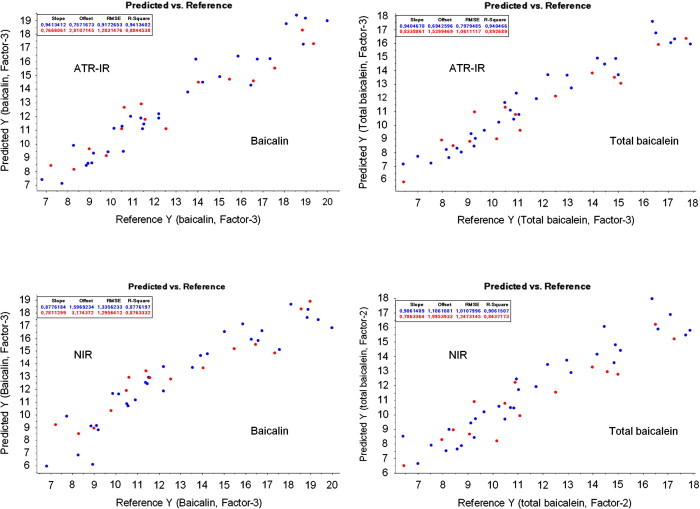

3.3. Spectroscopy

ATR-IR spectra and NIR spectra of the Chinese cultivated and wild-type samples are shown in Fig. 3. The predicted vs. reference plots of the best test-set calibrations are presented in Fig. 4. The intra-day and inter-day variabilities of ATR-IR and NIR are depicted in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

NIR spectra (A) after transformation log 1/R and ATR-IR spectra (B) after transformation log 1/R and baseline correction.

Fig. 4.

Predicted vs. reference plots for baicalin and total baicalein (test-set validation). The unit of x and y axis is %. Blue: calibration; red: validation. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3.1. ATR-IR

Spectral regions exhibiting a high noise level (4000–2997 cm−1 and 2807–1839 cm−1) were excluded and the spectral regions from 2996 to 2808 cm−1 and from 1838 to 650 cm−1 were selected for the calculation of the PLS model.

Following IR bands were assigned: 2900 cm−1 (C–H stretching vibrations), 3000–3600 cm−1 (O–H stretching of water), 1609 cm−1 (carbonyl stretching vibration) and 1000 cm−1 (C–O bending vibrations) [43], [44]. The quality parameters of the PLS-regressions for baicalin and total baicalein determination are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

ATR-IR PLS regression results for baicalin and total baicalein. The unit of SEC, SEP and SECV is %.

| ATR-IR | Baicalin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross validation |

Test-set validation |

|||||||||

| Factors | R2 | SEC | SECV | RPD | Factors | R2 | SEC | SEP | RPD | |

| 1st der | 2 | 0.88 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 2.80 | 3 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 1.31 | 2.91 |

| 2nd der | 4 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 1.22 | 3.14 | 4 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 1.35 | 2.84 |

| MSC | 4 | 0.85 | 1.20 | 1.49 | 2.57 | 4 | 0.80 | 1.01 | 1.74 | 2.20 |

| SNV | 4 | 0.85 | 1.19 | 1.49 | 2.56 | 4 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 1.69 | 2.27 |

| 2nd der+MSC | 2 | 0.89 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 2.92 | 4 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 1.43 | 2.68 |

| SNV+2nd der | 3 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 1.37 | 2.79 | 3 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 1.46 | 2.62 |

| 2nd der+SNV | 2 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 2.95 | 4 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 1.45 | 2.64 |

| ATR-IR | Total baicalein |

|||||||||

| Cross validation |

Test-set validation |

|||||||||

| Factors | R2 | SEC | SECV | RPD | Factors | R2 | SEC | SEP | RPD | |

| 1st der | 2 | 0.88 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 2.77 | 2 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 1.28 | 2.57 |

| 2nd der | 3 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 1.14 | 2.88 | 3 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 1.18 | 2.79 |

| MSC | 3 | 0.82 | 1.20 | 1.43 | 2.31 | 3 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.26 | 2.61 |

| SNV | 3 | 0.83 | 1.19 | 1.40 | 2.36 | 3 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 1.26 | 2.62 |

| 2nd der+MSC | 2 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 2.92 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 1.04 | 3.18 |

| SNV+2nd der | 3 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 2.73 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 1.18 | 2.79 |

| 2nd der+SNV | 2 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 2.94 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 3.24 |

3.3.1.1. Baicalin

The cross validation model gave the best results with second derivative (21) pre-treated spectra (SECV=1.22, RPD=3.14 and R 2=0.90). The first derivative (21) was the best spectra pre-treatment for test-set validation (SEP=1.31, RPD=2.91 and R 2=0.88).

3.3.1.2. Total baicalein

For the calibration of total baicalein content, the second derivative (13) continued with SNV as spectra pre-treatments reached the best quality parameters for test-set (SEP=1.02, RPD=3.24 and R 2=0.89) and cross validation (SECV=1.12, RPD=2.94 and R 2=0.89).

3.3.2. NIR

The selected spectral region was from 6300 to 4084 cm−1. The PLS-results for baicalin and total baicalein are depicted in Table 5.

Table 5.

NIR PLS regression results for baicalin and total baicalein. The unit of SEC, SEP and SECV is %.

| NIR | Baicalin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross validation |

Test-set validation |

|||||||||

| Factors | R2 | SEC | SECV | RPD | Factors | R2 | SEC | SEP | RPD | |

| 1st der | 3 | 0.83 | 1.45 | 1.63 | 2.34 | 4 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 1.77 | 2.16 |

| 2nd der | 3 | 0.87 | 1.26 | 1.43 | 2.67 | 3 | 0.86 | 1.21 | 1.67 | 2.29 |

| MSC | 4 | 0.70 | 1.72 | 2.12 | 1.80 | 4 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 2.40 | 1.59 |

| SNV | 5 | 0.77 | 1.56 | 1.89 | 2.02 | 5 | 0.76 | 1.55 | 2.17 | 1.76 |

| 2nd der+MSC | 2 | 0.86 | 1.34 | 1.46 | 2.60 | 3 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 1.52 | 2.50 |

| SNV+2nd der | 3 | 0.82 | 1.38 | 1.68 | 2.27 | 3 | 0.88 | 1.36 | 1.50 | 2.54 |

| 2nd der+SNV | 2 | 0.86 | 1.32 | 1.46 | 2.62 | 3 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 1.54 | 2.47 |

| NIR | Total baicalein |

|||||||||

| Cross validation |

Test-set validation |

|||||||||

| Factors | R2 | SEC | SECV | RPD | Factors | R2 | SEC | SEP | RPD | |

| 1st der | 2 | 0.81 | 1.28 | 1.45 | 2.26 | 2 | 0.78 | 1.16 | 1.48 | 2.22 |

| 2nd der | 2 | 0.84 | 1.20 | 1.35 | 2.43 | 2 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 1.19 | 2.76 |

| MSC | 4 | 0.70 | 1.47 | 1.83 | 1.80 | 4 | 0.78 | 1.44 | 1.52 | 2.16 |

| SNV | 5 | 0.76 | 1.32 | 1.65 | 2.00 | 5 | 0.75 | 1.24 | 1.64 | 2.01 |

| 2nd der+MSC | 2 | 0.84 | 1.23 | 1.36 | 2.42 | 2 | 0.83 | 1.13 | 1.34 | 2.46 |

| SNV+2nd der | 3 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 2.29 | 3 | 0.81 | 1.12 | 1.42 | 2.32 |

| 2nd der+SNV | 2 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 2.44 | 2 | 0.83 | 1.12 | 1.36 | 2.41 |

3.3.2.1. Baicalin

The second derivative (21) provided good results with test-set validation (SEP=1.50, RPD=2.54 and R 2=0.88), for cross validation SNV continued with second derivative (21) was found to be the best spectra pre-treatment (SECV=1.43, RPD=2.67 and R 2=0.87).

3.3.2.2. Total baicalein

Second derivative (11) and SNV resulted best for cross validation (SECV=1.35, RPD=2.44 and R 2=0.84) and second derivative (11) (SEP=1.19, RPD=2.76 and R 2=0.84) was the best pre-treatment for test-set validation.

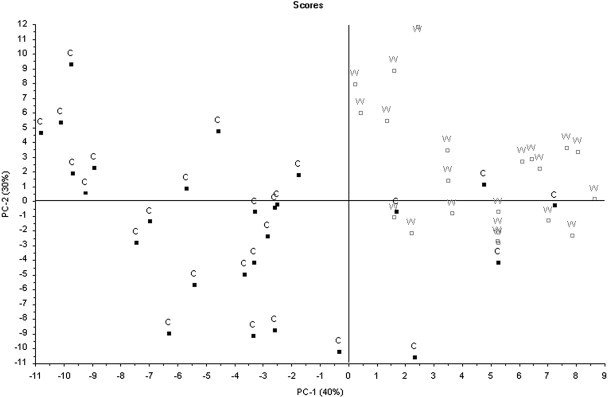

3.3.3. Qualitative analysis with ATR-IR

The score plot showing PC-1 vs. PC-2 of the Chinese cultivated and the Chinese wild-type samples are depicted in Fig. 5. The two groups of samples are separated in two clusters. Four Chinese cultivated samples are outliers and misinterpreted as Chinese wild-type samples.

Fig. 5.

Principal component analysis of China cultivated and China wild samples. Filled squares: cultivated; empty squares: wild-type.

4. Discussion

ATR-IR and NIR spectroscopy could achieve RPD values higher than 2.5 for baicalin and total baicalein content and therefore they can be considered as acceptable tools for screening purposes of Scutellariae radix samples [42]. For both methods the cross and test-set validation revealed very similar RPD values. Furthermore a very low number of factors (2–4) were needed to establish the models. In general ATR-IR spectroscopy showed a better performance for the quantification of the baicalin and total baicalein content than NIR. It was found that second derivative or SNV in combination with second derivative are the best spectra pre-treatments for the given application.

The qualitative investigation of the cultivated and the wild-type samples showed that the two groups can be distinguished by ATR-IR spectroscopy in hyphenation with PCA. Four of the Chinese cultivated samples were misinterpreted as Chinese wild-type samples. The reason for that could not be found.

5. Conclusion

This research shows that ATR-IR and NIR spectroscopy in combination with multivariate analysis are suitable for the quantification of the baicalin- and total baicalein-content in Scutellariae radix. It was found that ATR-IR provides better results than NIR spectroscopy. Furthermore it was proved that cultivated and wild-type samples of Scutellariae radix can be distinguished by ATR-IR in hyphenation with PCA.

References

- 1.Zhou Y., Lei H., Xu Y., Wei L., Xu X. Press of Chemical Industry; Beijing: 2002. Research Technology of Fingerprint of Traditional Chinese Medicine; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang W., Eisenbrand G. first ed. Springer; Berlin: 1992. Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin; pp. 919–929. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y.M., Sheu S.J. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1994;288:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi L., Zhou R., Wang Y., Zhu Y. J. Capillary Electrophor. 1998;5:181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin M.C., Tsai M.J., Wen K.C. J. Chromatogr. A. 1999;830:387–395. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto M., Ohta M., Kakamu H., Omori T. Chromatographia. 1993;35:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagara K., Ito Y., Oshima T., Misaki T., Murayama H., Itokawa H. J. Chromatogr. A. 1985;328:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao J., Xu Y., Wang Y., LUO G. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2004;24:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen K.C., Huang C.Y., Lu F.L. J. Chromatogr. A. 1993;631:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horvath C.R., Martos P.A., Saxena P.K. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1062:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu S., Sun A., Liu R. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1066:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motoo Y., Sawabu N. Cancer Lett. 1994;86:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikemoto S., Sugimura K., Yoshida N., Yasumoto R., Wada S., Yamamoto K., Kishimoto T. Urology. 2000;55:951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.So F.V., Guthrie N., Chambers A.F., Carroll K.K. Cancer Lett. 1997;112:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(96)04557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan F.L., Choi H., Chen Z., Chan P.S.F., Huang Y. Cancer Lett. 2000;160:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano H., Mizoguchi A., Fukuda K., Haramaki M., Ogasawara S., Momosaki S., Kojiro M. Cancer Res. 1994;54:448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanning H., Xiuyuan Z., Guifang C. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2000;3 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Z., Huang K., Yang X., Xu H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1999;1472:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heim K.E., Tagliaferro A.R., Bobilya D.J. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002;13:572–584. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cushnie T., Lamb A.J. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;26:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B., Fu T., Yan Y., Baylor N., Ruscetti F., Kung H. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 1993;39:119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen F., Chan K., Jiang Y., Kao R., Lu H., Fan K., Cheng V., Tsui W., Hung I., Lee T. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wartewig S., Neubert R.H.H., Drug Adv. Delivery Rev. 2005;57:1144–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Himmelsbach D.S., Hellgeth J.W., McAlister D.D. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:7405–7412. doi: 10.1021/jf052949g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Saona L., Koca N., Harper W., Alvarez V. J. Dairy Sci. 2006;89:1407–1412. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Saona L., Allendorf M. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;2:467–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022510-133750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz H., Baranska M., Quilitzsch R., Schütze W. Analyst. 2004;129:917–920. doi: 10.1039/b408930h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downey G. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 1998;17:418–424. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oelofse A., Malherbe S., Pretorius I., Du Toit M. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010;143:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixit V., Tewari J.C., Cho B.K., Irudayaraj J.M.K. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005;59:1553–1561. doi: 10.1366/000370205775142638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tena N., Aparicio R., García-González D.L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:9997–10003. doi: 10.1021/jf9012828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez-Saona L.E., Fry F.S., McLaughlin M.A., Calvey E.M. Carbohydr. Res. 2001;336:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steuer B., Schulz H., Läger E. Food Chem. 2001;72:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huck C., Guggenbichler W., Bonn G. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005;538:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulz H., Quilitzsch R., Krüger H. J. Mol. Struct. 2003;661:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz H., Pfeffer S., Quilitzsch R., Steuer B., Reif K. Planta Med. 2002;68:926–929. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otsuka M., Kato F., Matsuda Y. Analyst. 2001;126:1578–1582. doi: 10.1039/b103498g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.H. Li, L.-Q. Huang G, C. Jiang, W. LI, B. YANG, Chin. Pharm. J. (Zhongguo Yaoxue Zazhi), 15 (2008) 008.

- 39.Barnes R., Dhanoa M., Lister S.J. Appl. Spectrosc., 1989;43:772–777. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geladi P., MacDougall D., Martens H. Appl. Spectrosc., 1985;39:491–500. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savitzky A., Golay M.J.E. Anal. Chem., 1964;36:1627–1639. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams P.C., Sobering D. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 1993;1:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maquelin K., Kirschner C., Choo-Smith L.P., Van den Braak N., Endtz H.P., Naumann D., Puppels G. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2002;51:255–271. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(02)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X., Rasco B.A. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2012;52:853–875. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.511322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]