Abstract

This review provides an overview of triaging critically ill or injured patients during mass casualty incidents due to events such as disasters, pandemics, or terrorist incidents. Questions clinicians commonly have, including “what is triage?,” “when to triage?,” “what are the types of disaster triage?,” “how to triage?,” “what are the ethics of triage?,” “how to govern triage?,” and “what research is required on triage?,” are addressed.

Keywords: Triage, Mass casualty incident, Crisis response

Key points

-

•

Triage decision making is critical for a successful response to a mass casualty incident.

-

•

How triage is applied differs across the surge response spectrum from conventional to crisis response.

-

•

Disaster triage is a complex topic with which most clinicians have limited experience and often have difficulty in making the shift from the patient to population perspective to understand it well.

What is triage?

Intensive care clinicians are often uncertain as to what triage truly means and entails in a disaster situation. Their uncertainty likely stems from a lack of experience among clinicians in conducting triage in this context1 combined with a tendency to confuse it with the concepts of “triage” applied on a routine basis within the emergency room (ER)2 of hospitals or access to specialist services, such as cardiac catheterization and stroke services.

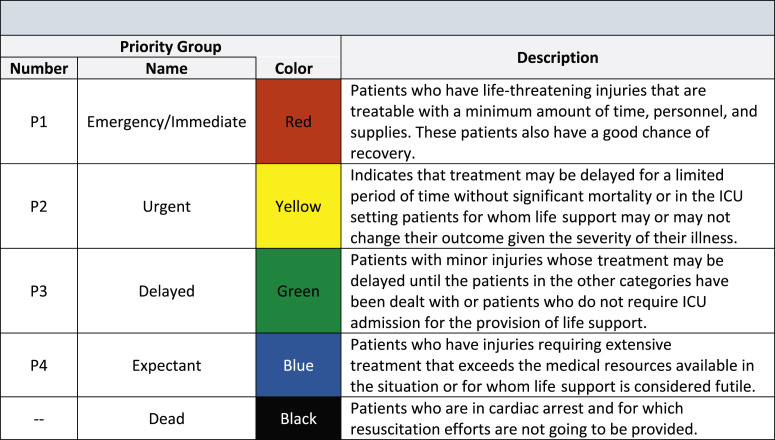

To understand the meaning of triage in a disaster setting, it is helpful to consider the origins of the word. Originating from the French verb “trier” meaning “to sort,” it was first used in the fifteenth century marketplaces in England and France to refer to grouping goods by quality and price.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Implicit in this early application of the term is the second component of triage, which is to assign some ranked value or priority to what is being sorted (Fig. 1 ). This prioritization aspect of triage is what is practiced on a routine basis in the ER and elsewhere but distinctly different from the full extent of triage used in a disaster.6 In disasters, in addition to sorting and prioritizing patients, triage also includes allocating scarce resources in order to “do the greatest good for the greatest number” (Box 1 ).1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Although this phrase easily slips off the tongue, many overlook its profound implications implicit in shifting decision making from a focus on individual patient outcomes to population-level outcomes.4, 5, 7 Although many clinicians have day-to-day experience with prioritizing patients for the benefit of that individual patient, very few clinicians have experience with population-level decision making during periods of resource scarcity.1, 6

Fig. 1.

Priority groups commonly used in triage for health care.

Box 1. Components of disaster triage.

Sorting

Prioritizing

Allocating resources

Bridging the concept between patients and populations outcomes are the terms “undertriage” and “overtriage.”2, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In undertriage. a patient is not recognized to be as sick or injured as they truly are, resulting in delayed treatment impacting the chance of survival for the individual as well as the overall survival rate within the population. With overtriage, a patient is misidentified as being more ill or injured than they actually are, and their care is prioritized higher than others who are actually in greater need. As a result of both the delayed treatment to the individual patients lower in the queue and the potentially inappropriate consumption of limited resources (staff, stuff, or space), the overall population outcome is worse.

When making triage decisions in resource-scarce situations, it is important to keep a few key concepts in mind. When evaluating a potential benefit of a treatment to a patient, one is attempting to determine the incremental benefit7, 15, 16 of that treatment compared with receiving a less resource-intensive or delayed treatment, but rarely does this ever mean no treatment. For example, it cannot be simply assumed that if a patient does not receive admission to intensive care and the provision of life support that they will certainly die.17 Furthermore, what is being considered is not a binary outcome between death and survival but rather the probability of death across an entire range of treatment options.7 Finally, it is important to remember that for both patients and society, survival in of itself is not the only outcome of concern; equally important is the quality of life for those who survive. Thus, the key factors being considered when making disaster triage decisions need to include survival, quality of life, and the resources necessary to achieve these outcomes (Box 2 ).18

Box 2. Disaster triage outcome considerations.

Survival

Quality of life

Resource consumption

Data from Christian MD, Fowler R, Muller MP, et al. Critical care resource allocation: trying to PREEDICCT outcomes without a crystal ball. Critical Care. 2013;17(1):3.

When to triage

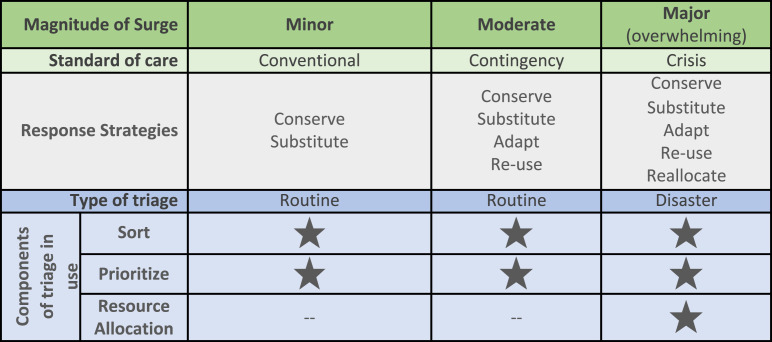

The Task Force for Mass Critical Care recommends that “in the event of an incident with mass critical care casualties, all hospitals within a defined geographic/administrative region, health authority, or health-care coalition implement a uniform triage process should critical care resources become scarce.”16 A subtler and more important nuance to this question is when to move from routine triage to disaster triage. The decision to implement “disaster triage” involves the additional component of resource allocation implicit in the meaning of the term “disaster.” A disaster can be defined as an event that results in injuries or loss of life and results in a demand for services that exceeds available resources.19 However, in terms of the health care response to an event, this binary concept of either being in a disaster or not is less helpful and likely impairs the response; thus, it is much more useful and common to consider the concepts of surge management.20, 21, 22, 23 Applying these principles, the clinician scales response strategies (conventional, contingency, or crisis) to the magnitude of the surge based on the balance between resource demand and supply, which is context dependent and will vary from incident to incident. In situations of minor or moderate surge whereby conventional and contingency strategies are used, the standard of care for patients remains relatively comparable to normal,24 and thus, only routine triage (sorting and prioritizing) should occur (Fig. 2 ). It is only during a major surge, when resources are, or will be, overwhelmed do crisis standards of care25 and response strategies involving the allocation (rationing) of resources come into play, necessitating “disaster triage.”16

Fig. 2.

Application of triage based on magnitude of surge.

(Adapted from Christian, M. D., et al. (2014). Introduction and executive summary: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest 146(4 Suppl): 8S-34S; and Data from Hick JL, Barbera JA, Kelen GD. Refining surge capacity: conventional, contingency, and crisis capacity. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(5_suppl):S59-S67.)

Making the transition to disaster triage, shifting the focus to population outcomes and implementing resource allocation processes, is a decision that carries with it significant implications for all involved (patients, clinicians, hospitals, and society) and thus requires appropriate approvals and governance.15 In most well-resourced societies, patients have access to health care resources even in situations wherein there are vanishingly small chances of them benefiting. Once a decision is made to implement disaster triage, many of these patients will have their access to these resources restricted with potential consequences for them.2 In addition, this transition is very difficult for clinicians who likely have never faced such situations in their careers.1, 26 Patients who are not triaged to immediate treatment should be reevaluated regularly and retriaged if their condition changes or the resource situation improves. All patients should receive some form of treatment, at a minimum, palliative care.1, 2, 27

Different types of disaster triage

The most common classification of triage is based on the location and level of care at which the triage takes place. Primary, secondary, and tertiary triage (Table 1 ) can be conducted for critically ill and injured patients and is the focus of this article. Other forms of triage critical care clinicians should also be aware of include public health triage and reverse triage.1, 16, 28, 29 Public health triage refers to triage protocols that distribute vaccinations or countermeasures in the event of an outbreak, pandemic, terrorism incident or biowarfare.9, 30, 31, 32, 33 Effective public health triage may decreased demand on critical care resources. Reverse triage34, 35, 36 is used to discharge patients at low risk of adverse events from either the intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital wards in turn to create ICU capacity.

Table 1.

Classification of triage by location

| Triage Type | Location | Priorities Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Field | Who to immediately treat on scene (triage sieve) and priorities for evacuation from scene (triage sort) |

| Secondary | Entry to ER | Who to prioritize for resuscitation and disposition to treatment areas within the ER and/or admission to hospital ward |

| Tertiary | Exit from ER or entry to ICU/OR | Who to prioritize for definitive/critical care (OR and admission to ICU) |

Regardless of the type of disaster, triage must address all sources of demand for critical care, not only those demands associated with the surge event itself.37 For example, following a natural disaster or terrorism attack creating an influx of trauma patients, the triage system must also be able to fairly allocate critical care resources to patients with medical conditions unrelated to the incident, such as respiratory failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome owing to sepsis or a woman with postpartum hemorrhage.2, 38

Primary Triage

Primary triage occurs in the field with the aim of determining priorities for treatment on scene and transport of patients to hospital. Although a large number of adult and pediatric protocols2, 38, 39, 40 have been developed, best practice in primary triage remains controversial because no protocol has been prospectively validated in a disaster39, 41 or accepted as being superior to all others.37, 40 Primary triage of the critically injured patient may be one of the most important decision points impacting the outcome for critically ill and injured patients.2 With the advances of Major Trauma Systems and wide spread utilization of Trauma Triage Tools on a routine basis, there have been recent suggestions made to restrict primary triage during conventional and contingency responses to a binary decision (triage to major trauma center vs triage to a regular ER).42 Two priority triage however is not a new concept, some military investigators have been advocating simplification of field triage for many years.1 Although Critical Care Physicians have often not been involved in primary triage in the past, with the general recognition of the need for critical care to occur outside of the walls of the ICU wherever patients need it, this is an area Critical Care Physicians should become more engaged in planning, overseeing, and delivering.

Secondary Triage

The objective of secondary triage varies depending on the nature of the incident. In a sudden onset43 kinetic event, such as an earthquake, bombing, or transport incident, where trauma is the primary “disease” being managed, the key objective of secondary triage is to determine the priority for treating patients arriving at the emergency department (ED). In the event of a delayed onset event, such as a pandemic or public health emergency, wherein the time course of the disease being treated is also more protracted, the primary objective of secondary triage is to determine who to admit to hospital because they are at high risk of deteriorating and may require intensive care or other high-dependency resources. In either case, one can think of secondary triage as occurring at the “front door” of the hospital.

Very few protocols have been developed to support secondary triage. Some hospitals apply primary triage protocols, such as simple triage and rapid treatment (START), for secondary triage; however, understandably, they perform poorly in this setting.44 Duplicating primary triage in hospital is not only unlikely to be effective for achieving the different objectives of secondary triage but also highly inefficient and fails to take into account the additional information available on which to base a secondary triage decision. In most situations, secondary triage is conducted by a single senior physician or surgeon or group of senior physicians or surgeons drawn from a variety of backgrounds, including emergency medicine, intensive care, or trauma surgery.28, 45, 46, 47 Toida and colleagues44 developed the Pediatric Physiological and Anatomical Triage Score specifically for pediatric secondary triage for trauma and CBRNE (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive) -related disasters. Pneumonia severity scores48, 49 have been investigated for secondary triage in pandemics but found to perform poorly. However, secondary triage criteria established by the UK health department specifically for a pandemic performed well in studies.48

Tertiary Triage

Tertiary triage occurs within the hospital with the objective of prioritizing patients, and if required allocating resources, for definitive care (operations or interventional radiology procedures) and intensive care (life support therapies). Tertiary triage decisions are generally more complex than earlier triage decisions given the larger amount of information available from multiple assessment points and investigations. Trauma tertiary triage is typically conducted by a senior clinician, usually a surgeon, anesthetist, or intensivist, based on their clinical experience.28, 36 Following the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome50 in 2003 and the development of the first protocol51 for ICU tertiary triage, there has been a significant amount of work to further develop such protocols.16, 18, 29, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61

Most well-developed and evaluated ICU triage protocols16, 29, 51, 57, 58, 60, 61 have used inclusion and exclusion criteria in combination with the sequential organ failure score (SOFA). In a conventional or contingency situation, when there is not an absolute shortfall of resources, the inclusion criteria for admission to ICU in most units will be patients who are at high risk of deteriorating and requiring initiation of life support or who are already receiving life support. When a shift is made to a crisis response, the inclusion criteria threshold changes to those who have already declared themselves to absolutely require life support. Similarly, exclusion criteria, which exist even during conventional and contingency situations,15, 62, 63 shift during a crisis such that patients with either baseline conditions or severity of illness/injury that places them in the realm of futility for immediate to short-term survival may be excluded. The use of the SOFA score in these protocols is not without controversy.64, 65, 66, 67 However, the latest iterations of an ICU triage protocol57 developed by the Influenza Pandemic ICU Triage Study Investigators of the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society clinical trials group improve on prior attempts and show significant promise.

To date, there are no reported incidents wherein any of these ICU triage protocols have been actively implemented to allocate scarce resources. However, when Hurricane Sandy struck New York City, Dr Laura Evans reported68 that the Ontario ICU Triage Protocol provided an important framework to plan if allocation was required for electrical power for ventilators. During the H1N1 pandemic, governments in Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand established triage protocols, based on the Ontario protocol,51 to be implemented if ICU resources were overwhelmed.58, 66

How to triage and who should do it

There are several key considerations when planning and delivering triage. These considerations include the critical decisions of who to select to do triage, whether triage should be conducted by individuals or teams, whether they should follow protocols or act on their clinical intuition, and finally, if using protocols, on what should the protocols be based.

Who Should Conduct Triage?

Effective triage depends on careful choice as to who should make triage decisions.2 As with all aspects of managing a major incident, compromises may have to be made based on the resources available and the context of the situation. Consistently, experts (and the public69) recommend that triage in mass casualty situations should be conducted by highly experienced physicians, who possess the necessary skill set (Box 3 ).1, 2, 16, 28, 29, 45, 46, 47, 51, 53, 54, 61, 70, 71, 72, 73 Having experienced physicians conduct triage applies to triage at all levels, including primary triage in the field. Previously, it was thought that in well-developed Emergency Medical Systems paramedics alone could undertake primary triage, and there was a limited role for physicians in this setting.2 However, more recent experience28, 74 and data show the benefit of properly trained and equipped prehospital physicians in primary triage, in particular when there are delays in evacuating patients from the scene to hospital.46 When an experienced physician/surgeon is not available to triage, then the next most clinically trained and experienced providers should undertake triage.

Box 3. Essential triage officer skills.

Extensive clinical experience

Strong leadership

Effective communication

Agile decision making

There are several reasons senior physicians and surgeons are recommended (and found to perform better6, 75) over other less highly trained or experienced providers. First, there is some evidence that their knowledge and understanding of triage may be better,6 but that seems to be a minor component. Likely the critical factor is their clinical experience impacting their ability to rapidly identify “sick from well,” combined with their ability to understand patients’ overall clinical course and treatment needs (the “big picture”).1 Providers such as paramedics rarely are afforded the opportunity to have longer-term follow-up on their patients or to see how they progress over the course of their acute illness/injury or respond to definitive treatments. Just as it is important for the surgeon or intensivist doing tertiary triage to understand what will happen in the operating room (OR)/ICU, so too will triage be most effective if primary triage decisions are informed by an understanding of what resources the patient requires on arrival to hospital and the systems in place to provide them. Finally, senior physicians, in particular, intensivists and emergency medicine physicians who manage multiple patients in large ICUs or EDs on a daily basis, are well accustomed and experienced in making complex, critical decisions with limited information.76, 77, 78, 79 This type of experience makes them uniquely well suited for both triage and leadership in major incidents.

Given that the key objective of the triage officer is to save the most lives, the senior triage officer should have ultimate control over all resources within their area of operation (department) and thus ultimately command the situation. Even in the military, Swan and Swan1 point out that “In time of triage, the triage officer outranks the hospital commander, in practice, and this needs to be clearly understood by all involved, including the commanding officer!”1 At the organizational level, it is also important to ensure a similarly experienced physician or surgeon is in command to appropriately support the department-level triage officers.45

Should Individuals or Teams Triage?

Although it seems straightforward, this question is not as simple as it sounds. The crux of the issue is whether triage decisions, at the coal face in the midst of a mass casualty situation, should be made by an individual or a committee. Most recommendations suggest an individual triage officer1, 2, 16, 28, 29, 45, 46, 47, 51, 53, 70, 71, 72, 73 rather than a committee.54, 60 However, even in those studies that do recommend a single person ultimately makes the triage decision, most recommend that a multidisciplinary team work in conjunction with and support the triage officer through obtaining information, undertaking assessments, and so forth. Following good leadership principles, the triage officer should take input from his/her team members; thus, having a single final decision maker does not mean decisions are made in isolation. Multiple triage officers (and supporting teams) may be required to manage casualty volumes. Although some advocate committee-based triage decisions, it is unlikely that primary, secondary, or tertiary triage decisions could ever be effectively implemented on scale with the required time dependencies for such decisions, including decisions regarding critical care in a mass casualty incident. Reverse triage decisions, including the withdrawal of life support, may be more amenable to a committee-type decision given the lack of time pressures for these decisions.

Should Protocols Be Used for Triage?

The primary benefits of using a protocol for triage are 2-fold: first, it provides a decision support aid in a time of crisis to improve performance; second, if designed and applied appropriately, it should improve consistency of decisions made as well as improve outcomes. For any triage protocol to be successful, it must be able to distinguish those most in need and most likely to benefit from therapy. Poorly performing protocols may lead to worse outcomes than other options, such as first come, first served.80 The alternative to using a protocol is to rely solely on clinician intuition, “gut instinct,” for triage decisions.2, 40, 70

Much work has recently been undertaken attempting to develop protocols to support tertiary triage. Given that any ICU triage protocol must apply to all patients being considered for ICU admission, most of the protocols have been based on physiologic prognostic scores, such as the SOFA score.16, 29, 51, 57, 58, 60, 81 Although this addresses the need for a score that applies to all, there is concern about certain subjective aspects of the SOFA score (including Glasgow Coma Scale measurement and level of inotrope support), its lack of applicability for pediatric patients,82 as well as concerns about the performance of the score.65, 67, 83 However, the studies questioning SOFA performance have done so based on individual patient outcome analyses not population-level outcomes (overall survival), which should be the basis of triage evaluations.7 It may be possible to combine multiple disease-specific scores, such as the injury severity score (ISS), revised trauma score (RTS), burn scores, or pneumonia scores, for triage using a computer decision support algorithm and common outcome measures.18 However, current evidence suggests the RTS72 and ISS84 perform poorly for triage.

What are the ethics of triage and how to govern triage?

A review of the ethics of triage is a complete article unto itself, and several excellent reviews already exist.85, 86, 87, 88 Key concepts related to the ethics of triage are listed in Table 2 . Although there is no single agreed upon “right” ethical principle on which to base triage,54 it is generally accepted that population (public health) ethical frameworks should be used rather than the traditional framework of medical ethics. Many clinicians can find this conceptual transition difficult to make. Further complicating matters is that ethical perspectives vary at the societal level around the world on many topics, including their views on the role of clinicians in decision making and use of “lotteries” rather than triage for the allocation of scarce resources.26, 60, 69, 89

Table 2.

Ethical guide for pandemic planning

| Substantive Values to Guide Ethical Decision Making1 | Procedural Values to Guide Ethical Decision Making1 | Ethical Principles Possible to Inform Triage |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Data from University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics Pandemic Influenza Working Group. Stand on Guard for Thee. Ethical considerations in preparedness planning for pandemic influenza. Toronto: University of Toronto;2005

Effective governance of triage requires a legal basis authorizing its application as well as infrastructure mechanisms to ensure it is conducted appropriately (Box 4 ). Several publications by public health legal experts explore in detail the issues surrounding the legislative framework and other legal issues related to disaster triage.90, 91, 92 Unfortunately, the legal and governance aspects of triage are often neglected by governments, and health care workers will be left to manage in a disaster with limited support and a lack of guidance. Addressing the gaps in these areas should be a priority for government officials and emergency planners.

Box 4. Infrastructure and processes required for effective triage governance.

-

•

Legislative framework for the allocation of scarce resources in a disaster

-

•

Uniform triage policies and processes across a geographic or administrative region

-

•

Mechanism for a public body with adequate situational awareness and legal authority to initiate rationing (resource allocation) aspect of triage when resources have become scarce

-

•

System to develop triage policies/protocols and provide oversight of triage decisions

-

•

Effective command and control process (eg, Incident Management System)

-

•

Effective communication system and process for sharing situational awareness of resource status

-

•

Training for triage officers

-

•

Psychological support system for triage officers and health care workers

Data from Christian MD, Sprung CL, King MA, et al. Triage: Care of the Critically Ill and Injured During Pandemics and Disasters: CHEST Consensus Statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e61S-74S.

What research is required on triage?

The research literature on triage in disasters remains relatively limited, and what data are available are thought to be of low quality.37, 93 Some notable exceptions are recent examples of high-quality research into ICU triage ethics26, 69 and triage protocol development.57, 58 To date, there has been no prospective validation of the major incident triage tools during a major incident.39 There are two common errors found among the triage research literature worth highlighting with the hope to prevent others from making similar mistakes in the future. The first error is to attempt to use general ICU populations from non-resource-scarce scenarios to test or derive triage protocols for use in mass casualty situations and the second is to fail to understand the different aims of secondary and tertiary triage.

The research by Morton and colleagues94 provide an example of both errors in that they attempt to evaluate the Ontario Triage Protocol51 using a population that includes patients who are not admitted to intensive care as well as those in ICU but who do not require life support. Thus, they include a population that does not meet the inclusion criteria for which the Ontario Triage Protocol was designed. In addition, the focus of Morton’s research question is to “predict the need for mechanical ventilation and critical care admission.” As discussed earlier, this is posed as an erroneous question of tertiary triage in a mass casualty situation and would actually guide who to prioritize for hospital admission (secondary triage). Rather, tertiary triage occurs among those who have already declared themselves to require life support and aims to predict who will benefit from it most and lead to the overall highest survival in the population. The work by Adeniji and Cusack95 provides another example of these same errors being made.95 The first step to conducting high-quality research in triage is to understand the underlying principles of triage.

Summary

Triage decision making is critical for a successful response to a mass casualty incident. How triage is applied differs across the surge response spectrum from conventional to crisis response. Mass casualty triage is a complex topic with which most clinicians have limited experience and with which most clinicians often have difficulty in making the shift from the patient to population perspective to understand it well. Further training and research are necessary to advance this field and better prepare intensive care clinicians to respond to disasters.

References

- 1.Swan K.G., Swan K.G., Jr. Triage: the past revisited. Mil Med. 1996;161(8):448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy K., Aghababian R.V., Gans L., et al. Triage: techniques and applications in decision making. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28(2):136–144. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakao H., Ukai I., Kotani J. A review of the history of the origin of triage from a disaster medicine perspective. Acute Med Surg. 2017;4(4):379–384. doi: 10.1002/ams2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iserson K.V., Moskop J.C. Triage in medicine, part I: concept, history, and types. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veatch R.M. Disaster preparedness and triage: justice and the common good. Mt Sinai J Med. 2005;72(4):236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janousek J.T., Jackson D.E., De Lorenzo R.A., et al. Mass casualty triage knowledge of military medical personnel. Mil Med. 1999;164(5):332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomersall C.D., Joynt G.M. What is the benefit in triage? Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):911–912. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820b7415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker M.S. Creating order from chaos: part I: triage, initial care, and tactical considerations in mass casualty and disaster response. Mil Med. 2007;172(3):232–236. doi: 10.7205/milmed.172.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkle F.M. Population-based triage management in response to surge-capacity requirements during a large-scale bioevent disaster. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(11):1118–1129. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moskop J.C., Iserson K.V. Triage in medicine, part II: underlying values and principles. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong J.H., Hammond J., Hirshberg A., et al. Is overtriage associated with increased mortality? The evidence says "yes". Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(1):4–5. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31816476c0. [author reply: 5–6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hupert N., Hollingsworth E., Xiong W. Is overtriage associated with increased mortality? Insights from a simulation model of mass casualty trauma care. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1(1 Suppl):S14–S24. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31814cfa54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frykberg E.R. Medical management of disasters and mass casualties from terrorist bombings: how can we cope? J Trauma. 2002;53(2):201–212. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frykberg E.R. Terrorist bombings in Madrid. Crit Care. 2005;9(1):20–22. doi: 10.1186/cc2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanch L., Abillama F.F., Amin P., et al. Triage decisions for ICU admission: report from the Task Force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care. 2016;36:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian M.D., Sprung C.L., King M.A., et al. Triage: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e61S–e74S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joynt G.M., Gomersall C.D., Tan P., et al. Prospective evaluation of patients refused admission to an intensive care unit: triage, futility and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(9):1459–1465. doi: 10.1007/s001340101041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christian M.D., Fowler R., Muller M.P., et al. Critical care resource allocation: trying to PREEDICCT outcomes without a crystal ball. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):3. doi: 10.1186/cc11842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis C.P., Aghababian R.V. Disaster planning, Part I. Overview of hospital and emergency department planning for internal and external disasters. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14(2):439–452. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hick J.L., Barbera J.A., Kelen G.D. Refining surge capacity: conventional, contingency, and crisis capacity. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(2 Suppl):S59–S67. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31819f1ae2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hick J.L., Christian M.D., Sprung C.L. Chapter 2. Surge capacity and infrastructure considerations for mass critical care. Recommendations and standard operating procedures for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(Suppl 1):S11–S20. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hick J.L., Einav S., Hanfling D., et al. Surge capacity principles: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e1S–e16S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hick J.L., Hanfling D., Burstein J.L., et al. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christian M.D., Devereaux A.V., Dichter J.R., et al. Introduction and executive summary: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):8S–34S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altevogt B.M., Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Guidance for Establishing Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: a letter report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biddison E.L.D., Gwon H.S., Schoch-Spana M., et al. Scarce resource allocation during disasters: a mixed-method community engagement study. Chest. 2018;153(1):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nouvet E., Sivaram M., Bezanson K., et al. Palliative care in humanitarian crises: a review of the literature. Int J Humanitarian Action. 2018;3(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orban J.C., Quintard H., Ichai C. ICU specialists facing terrorist attack: the Nice experience. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(5):683–685. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devereaux A.V., Dichter J.R., Christian M.D., et al. Definitive care for the critically ill during a disaster: a framework for allocation of scarce resources in mass critical care: from a Task Force for Mass Critical Care summit meeting, January 26-27, 2007, Chicago, IL. Chest. 2008;133(5 Suppl):51S–66S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard M.J., Brillman J.C., Burkle F.M. Infectious disease emergencies in disasters. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14(2):413–428. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein K.R., Pepe P.E., Burkle F.M., et al. Evolving need for alternative triage management in public health emergencies: a Hurricane Katrina case study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(Suppl 1):S40–S44. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181734eb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sox H.C. A triage algorithm for inhalational anthrax. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(5 Pt 1):379–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_1-200309020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cone D.C., Koenig K.L. Mass casualty triage in the chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear environment. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):287–302. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satterthwaite P.S., Atkinson C.J. Using 'reverse triage' to create hospital surge capacity: Royal Darwin Hospital's response to the Ashmore Reef disaster. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(2):160–162. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.098087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelen G.D., Troncoso R., Trebach J., et al. Effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):e164829. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Einav S., Hick J.L., Hanfling D., et al. Surge capacity logistics: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e17S–e43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timbie J.W., Ringel J.S., Fox D.S., et al. Systematic review of strategies to manage and allocate scarce resources during mass casualty events. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):677–689.e101. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arshad F.H., Williams A., Asaeda G., et al. A modified simple triage and rapid treatment algorithm from the New York City (USA) Fire Department. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2015;30(2):199–204. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X14001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vassallo J., Beavis J., Smith J.E., et al. Major incident triage: derivation and comparative analysis of the modified physiological triage tool (MPTT) Injury. 2017;48(5):992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein K.R., Burkle F.M., Jr., Swienton R., et al. Qualitative analysis of surveyed emergency responders and the identified factors that affect first stage of primary triage decision-making of mass casualty incidents. PLoS Curr. 2016;8 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.d69dafcfb3ad8be88b3e655bd38fba84. [pii:ecurrents.dis.d69dafcfb3ad8be88b3e655bd38fba84] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jenkins J.L., McCarthy M.L., Sauer L.M., et al. Mass-casualty triage: time for an evidence-based approach. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23(1):3–8. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan London Major Trauma Networks: response to mass casualty incident. Center for Trauma Sciences; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devereaux A., Christian M.D., Dichter J.R., et al. Care TFfMC Summary of suggestions from the task force for mass critical care summit, January 26-27, 2007. Chest. 2008;133(5 Suppl):1S–7S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toida C., Muguruma T., Abe T., et al. Introduction of pediatric physiological and anatomical triage score in mass-casualty incident. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018;33(2):147–152. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X18000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Einav S., Spira R.M., Hersch M., et al. Surgeon and hospital leadership during terrorist-related multiple-casualty events: a coup d'etat. Arch Surg. 2006;141(8):815–822. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.8.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hick J.L., Hanfling D., Cantrill S.V. Allocating scarce resources in disasters: emergency department principles. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shirley P.J., Mandersloot G. Clinical review: the role of the intensive care physician in mass casualty incidents: planning, organisation, and leadership. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):214. doi: 10.1186/cc6876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myles P.R., Semple M.G., Lim W.S., et al. Predictors of clinical outcome in a national hospitalised cohort across both waves of the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic 2009-2010 in the UK. Thorax. 2012;67(8):709–717. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Commons R.J., Denholm J. Triaging pandemic flu: pneumonia severity scores are not the answer. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(5):670–673. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christian M.D., Poutanen S.M., Loutfy M.R., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1420–1427. doi: 10.1086/420743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Christian M.D., Hawryluck L., Wax R.S., et al. Development of a triage protocol for critical care during an influenza pandemic. CMAJ. 2006;175(11):1377–1381. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christian M.D., Hamielec C., Lazar N.M., et al. A retrospective cohort pilot study to evaluate a triage tool for use in a pandemic. Crit Care. 2009;13(5):R170. doi: 10.1186/cc8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christian M.D., Toltzis P., Kanter R.K., et al. Treatment and triage recommendations for pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(6):S109–S119. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eastman N., Philips B., Rhodes A. Triaging for adult critical care in the event of overwhelming need. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(6):1076–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Powell T., Christ K.C., Birkhead G.S. Allocation of ventilators in a public health disaster. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(1):20–26. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181620794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubinson L., Christian M.D. Allocating mechanical ventilators during mass respiratory failure: kudos to New York State, but more work to be done. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(1):7–10. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318164d04d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheung W., Myburgh J., Seppelt I.M., et al. Development and evaluation of an influenza pandemic intensive care unit triage protocol. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14(3):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheung W.K., Myburgh J., Seppelt I.M., et al. A multicentre evaluation of two intensive care unit triage protocols for use in an influenza pandemic. Med J Aust. 2012;197(3):178–181. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gall C., Wetzel R., Kolker A., et al. Pediatric triage in a severe pandemic: maximizing survival by establishing triage thresholds. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1762–1768. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daugherty Biddison E.L., Faden R., Gwon H.S., et al. Too many patients…a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2018;155(4):848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christian M.D., Joynt G.M., Hick J.L., et al. Chapter 7. Critical care triage. Recommendations and standard operating procedures for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(Suppl 1):S55–S64. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1765-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zawacki B.E. ICU physician's ethical role in distributing scarce resources. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(1):57–60. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198501000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fair allocation of intensive care unit resources. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(4 Pt 1):1282–1301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.ats7-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zygun D.A., Laupland K.B., Fick G.H., et al. Limited ability of SOFA and MOD scores to discriminate outcome: a prospective evaluation in 1,436 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52(3):302–308. doi: 10.1007/BF03016068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan Z., Hulme J., Sherwood N. An assessment of the validity of SOFA score based triage in H1N1 critically ill patients during an influenza pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(12):1283–1288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guest T., Tantam G., Donlin N., et al. An observational cohort study of triage for critical care provision during pandemic influenza: 'clipboard physicians' or 'evidenced based medicine'? Anaesthesia. 2009;64(11):1199–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shahpori R., Stelfox H.T., Doig C.J., et al. Sequential organ failure assessment in H1N1 pandemic planning. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):827–832. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McKnight W. Ready or not? Most ICUs not as prepared for disaster as they think. Chest Physician. November 25, 2013.

- 69.Cheung W., Myburgh J., McGuinness S., et al. A cross-sectional survey of Australian and New Zealand public opinion on methods to triage intensive care patients in an influenza pandemic. Crit Care Resusc. 2017;19(3):254–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hashimoto A., Ueda T., Kuboyama K., et al. Application of a first impression triage in the Japan railway west disaster. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67(3):171–176. doi: 10.18926/AMO/50410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shirley P.J. Critical care delivery: the experience of a civilian terrorist attack. J R Army Med Corps. 2006;152(1):17–21. doi: 10.1136/jramc-152-01-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burkle F.M., Jr., Newland C., Orebaugh S., et al. Emergency medicine in the Persian Gulf War---part 2. Triage methodology and lessons learned. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(4):748–754. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burkle F.M., Jr., Orebaugh S., Barendse B.R. Emergency medicine in the Persian Gulf War--part 1: preparations for triage and combat casualty care. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(4):742–747. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blank-Reid C., Santora T.A. Developing and implementing a surgical response and physician triage team. Disaster Manag Response. 2003;1(2):41–45. doi: 10.1016/s1540-2487(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Follmann A., Ohligs M., Hochhausen N., et al. Technical support by smart glasses during a mass casualty incident: a randomized controlled simulation trial on technically assisted triage and telemedical app use in disaster medicine. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e11939. doi: 10.2196/11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reader T.W., Flin R., Cuthbertson B.H. Team leadership in the intensive care unit: the perspective of specialists. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(7):1683–1691. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318218a4c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malhotra S., Jordan D., Shortliffe E., et al. Workflow modeling in critical care: piecing together your own puzzle. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(2):81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laxmisan A., Hakimzada F., Sayan O.R., et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(11–12):801–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patel V.L., Zhang J., Yoskowitz N.A., et al. Translational cognition for decision support in critical care environments: a review. J Biomed Inform. 2008;41(3):413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kanter R.K. Would triage predictors perform better than first-come, first-served in pandemic ventilator allocation? Chest. 2015;147(1):102–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hick J.L., O'laughlin D.T. Concept of operations for triage of mechanical ventilation in an epidemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(2):223–229. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.King M.A., Kissoon N. Triage during pandemics: difficult choices when business as usual is not an ethically defensible option. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1793–1795. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ashton-Cleary D., Tillyard A., Freeman N. Intensive care admission triage during a pandemic: a survey of the acceptability of triage tools. J Intensive Care Soc. 2011;12(3):180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vassallo J., Smith J.E., Bruijns S.R., et al. Major incident triage: a consensus based definition of the essential life-saving interventions during the definitive care phase of a major incident. Injury. 2016;47(9):1898–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Antommaria A.H.M., Powell T., Miller J.E., et al. Ethical issues in pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(6):S163–S168. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a88b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Group UoTJCfBPIW . University of Toronto; Toronto: 2005. Stand on Guard for Thee. Ethical considerations in preparedness planning for pandemic influenza. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ram-Tiktin E. Ethical considerations of triage following natural disasters: the IDF experience in Haiti as a case study. Bioethics. 2017;31(6):467–475. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Biddison L.D., Berkowitz K.A., Courtney B., et al. Ethical considerations: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e145S–e155S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Winsor S., Bensimon C.M., Sibbald R., et al. Identifying prioritization criteria to supplement critical care triage protocols for the allocation of ventilators during a pandemic influenza. Healthc Q. 2014;17(2):44–51. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2014.23833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gostin L.O., Hanfling D. National preparedness for a catastrophic emergency crisis standards of care. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2365–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Powell T., Dan H., Gostin L.O. Emergency preparedness and public health: the lessons of Hurricane Sandy. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2569–2570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.108940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Courtney B., Hodge J.G., Jr., Toner E.S., et al. Legal preparedness: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e134S–e144S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morton M.J., DeAugustinis M.L., Velasquez C.A., et al. Developments in surge research priorities: a systematic review of the literature following the Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference, 2007-2015. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(11):1235–1252. doi: 10.1111/acem.12815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morton B., Tang L., Gale R., et al. Performance of influenza-specific triage tools in an H1N1-positive cohort: P/F ratio better predicts the need for mechanical ventilation and critical care admission. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):927–933. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Adeniji K.A., Cusack R. The Simple Triage Scoring System (STSS) successfully predicts mortality and critical care resource utilization in H1N1 pandemic flu: a retrospective analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R39. doi: 10.1186/cc10001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]