Abstract

A 37-year-old man was presented with incidental findings of neutropenia, atypical lymphocytosis, thrombocytopenia and deranged liver parenchymal enzymes. Four days later, he developed fever, sore throat and cervical lymphadenopathy, compatible with mononucleosis-like illness (MLI). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and viral culture of the nasopharyngeal swab showed human metapneumovirus (hMPV). There was a ≥4-fold rise in IgG against hMPV. This is the first case report illustrating the natural clinical course of hMPV-related MLI.

Keywords: Human metapneumovirus, Infectious mononucleosis, Mononucleosis-like illness

Introduction

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is a recently identified respiratory virus belonging to the family of Paramyxoviridae.1 It is associated with acute respiratory tract infections in children.2 Clinical syndromes described in adults include influenza-like illness, bronchitis, and exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3 Severe pneumonia can also occur in the elderly and immunocompromised patients.4 Several hMPV outbreaks involving adults residing in psychiatric units and long-term care facilities have been reported,5, 6 in which 12% of all cases died in one study.6 In this case report, we present the natural evolution of mononucleosis-like illness (MLI) due to hMPV in an immunocompetent adult.

Case report

A 37-year-old male health care worker was presented with an incidental finding of abnormal blood tests during routine health check. The complete blood picture revealed a normal total white cell count of 4.40 × 109/L; however, there were neutropenia (0.53 × 109/L, normal range 2.2–6.7 × 109/L), lymphocytosis (3.48 × 109/L, normal range 1.2–3.4 × 109/L) and thrombocytopenia with platelet of 56 × 109/L (normal range 170–380 × 109/L). A review of the blood smear showed the presence of atypical lymphocytes (0.13 × 109/L, normal range 0), and there was no platelet clumping ( Fig. 1a). The liver parenchymal enzymes were deranged with elevation of alanine aminotransferase (56 U/L, normal range 6–53 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (46 U/L, normal range 13–33 U/L), but the gamma-glutamyltransferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin and the renal function tests were within normal limits. In view of the abnormal blood picture, flow cytometry studies were performed the next day, which demonstrated a reversed CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.3 suggestive of a reactive change due to viral infection. Extensive microbiological investigations for MLI were performed on the same day. Serum for heterophil antibodies by Monospot test was negative. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) serology showed a past infection with positive EBNA and VCA IgG. The cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG was positive but the IgM was negative. The CMV pp65 antigenemia was negative. The serum HIV antibody, toxoplasma and parvovirus IgM and IgG were also negative.

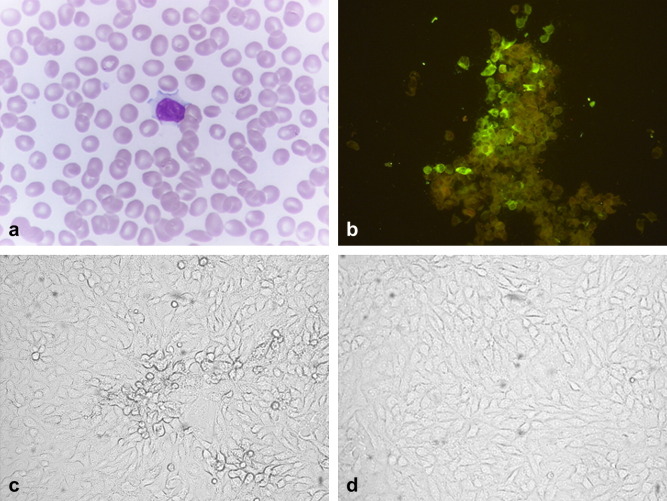

Figure 1.

(a) Hematoxylin and Eosin stains of peripheral blood smear showing atypical lymphocyte. The atypical lymphocyte is larger than a mature lymphocyte. The periphery of the cell is indented by surrounding cells producing a scalloped appearance. The cytoplasm is abundant and vacuolated giving a foamy appearance; (b) patient's serum showed specific antibody response against hMPV-infected FRhK-4 cell smear by indirect immunofluorescence; (c) CPE with syncytia was developed at day 5 after inoculation of patient's nasopharyngeal wash on FRhK-4 cells; and (d) no CPE was found on uninfected FRhK-4 cells.

On day 4 after the abnormal blood tests, the patient developed symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection, including a sore throat, rhinorrhoea, productive cough and myalgia. He also developed bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, which progressively increased until day 7. In view of the multiple cervical lymphadenopathy and hematological abnormalities, computer tomography with contrast of the neck, thorax and abdomen was performed to assess the extent of lymphadenopathy. There were multiple mildly enlarged nodes along the right jugulo-digastric chain at levels III, IV and V. The largest one measured 1.7 × 1.2 × 2.5 cm at the apex of the right posterior triangle of the neck, but no enlarged lymphadenopathy in other regions.

Further microbiological investigations were performed upon symptoms onset, including nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) and throat swab for bacterial culture, viral antigen detection of influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza types 1–3, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and viral culture. Nasopharyngeal swab and buffy coat were tested for hMPV, rhinovirus, human coronavirus (OC43, 229E, NL63), and enterovirus by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Buffy coat for human herpesvirus types 6–8 and parvovirus PCR were also assayed.

NPS was positive for a fragment of the polymerase gene of hMPV by RT-PCR, which was confirmed by sequencing of the PCR products. Acute and convalescent sera taken 14 days apart were tested for IgG antibody to hMPV and showed a ≥4-fold rising titre from 1 in 20 to 1 in 640. Viral culture of the NPS was also positive for hMPV. The clinical isolate was found to be genotype B. All other microbiological investigations were negative. Repeated blood tests showed a gradual recovery of blood count with decreasing atypical lymphocytosis ( Table 1). The complete blood picture and liver parenchymal enzymes normalized 14 days later. Upon further questioning, the patient's 26-month-old daughter had history of fever of 39.5 °C 2 days before the health check. The baby also developed similar upper respiratory symptoms to the patient. Apart from his daughter, the patient had no known contact with other people with upper respiratory tract symptoms for at least 2 weeks before onset of illness.

Table 1.

Serial hematological and biochemical results during the natural course of hMPV-related MLI

| Baseline (1 year ago) | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 15 | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White cell | 5.4 | 4.4 | 4.27 | 4.95 | 4.56 | 5.68 | 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 16.5 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 16.0 | g/dL |

| Platelet | 190 | 56 | 134 | 154 | 179 | 227 | 109/L |

| Neutrophil | 3.10 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.54 | 2.88 | 109/L |

| Lymphocyte | 1.60 | 3.48 | 2.52 | 3.22 | 2.39 | 2.15 | 109/L |

| Atypical lymphocyte | 0.13 | 0.2 | 109/L | ||||

| Remark of atypical lymphocyte | Total lymphocyte count (3.7%) | Not done | Total lymphocyte count (6.2%) | A small number seen | Very occasional | ||

| Albumin | 47 | 47 | 45 | 44 | 46 | 44 | g/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 71 | 65 | 69 | 65 | 67 | 73 | U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 29 | 56 | 55 | 54 | 56 | 28 | U/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 25 | 46 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 21 | U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase | 30 | 41 | 42 | 44 | 39 | 36 | U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 261 | 475 | 466 | 418 | 406 | 287 | U/L |

Methods of laboratory investigation

An aliquot of NPS sample was tested for hMPV. Viral RNA was extracted directly from NPS specimens using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA pellet was resuspended in 10 μl of DNase-free, RNase-free double-distilled water and was used as the template for RT-PCR. A 267-bp fragment of the polymerase gene of hMPV was amplified by RT-PCR using primers (LPW 4764 5′-TGGTGYCARAARYTMTGGACA-3′ and LPW 4765 5′-AAAYTGRAGATCYCTTGATATATA-3′). The RNA was converted to cDNA by a combined random-priming strategy using the SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 1 μl of cDNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.01% gelatin), 200 μM of each dNTPs and 1.0 U Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). The mixtures were amplified in 40 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min in an automated thermal cycler (Perkin–Elmer Cetus, Gouda, The Netherlands). The PCR products were gel-purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). Both strands of the PCR products were sequenced twice with an ABI Prism 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), using the PCR primers.

For hMPV culture, FRhK-4 cell monolayers in culture tubes were inoculated with 200 μl of NPS and the cells were maintained in serum free medium MEM (minimal essential medium) with trypsin (2.5 μg/ml), and incubated at 35 °C for up to 14 days. They were examined daily for cytopathic effect (CPE), immunofluorescence done on fixed cell smears when CPE appeared or at the end of the incubation period.

hMPV antibody detection was performed using indirect immunofluorescence test of hMPV-infected cell smears (Fig. 1b–d). Briefly, serum with serial 2-fold dilutions starting from 1 in 10 was screened on infected and noninfected control cells for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 min each time, and then anti-human IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugates (INOVA Diagnostic, San Diego) were added and the cells were further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The IF-dye-stained cells were examined at a ×20 magnification under a UV fluorescence microscope.

Discussion

Infectious mononucleosis is classically associated with EBV. However, many other infections can mimic this condition and are labeled as MLI. Other than EBV, CMV has been considered the most common infective cause of MLI, and is associated with fever, atypical lymphocytosis and mild hepatitis but sore throat and lymphadenopathy are typically absent. Other infective causes include herpes simplex virus type I, human herpesvirus type 6, HIV, parvovirus, adenovirus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and toxoplasma.7 However, there has been no previous report suggesting the relationship between MLI and hMPV.

We have presented in this case report a patient with MLI due to hMPV. The presence of hMPV is documented by PCR and later confirmed by viral culture. There was evidence of acute hMPV infection as shown by a ≥4-fold rise of the anti-hMPV antibody in paired serum. The clinical manifestation of MLI is supported by abnormal laboratory findings, including the presence of atypical lymphocytes and abnormal levels of liver parenchymal enzymes. Other infectious causes of MLI have been excluded by extensive microbiological investigations.

The incidental finding of abnormal blood tests during health checkup provides a unique opportunity to study the natural progression of the disease from an asymptomatic stage. The first blood test from the asymptomatic patient, which was taken 2 days after his daughter's symptom onset, already demonstrated atypical lymphocytes in the peripheral blood film. This preceded clinical symptoms by 4 days. Previous studies suggested that the incubation period of hMPV to be 4–6 days based on symptoms onset.8 This case demonstrates that hematological abnormalities can be demonstrated as early as 2 days after acquiring the virus. However, we do not have recent serial blood tests before these abnormal results and, therefore, we are not able to pinpoint the exact onset of abnormal blood test.

Another prominent feature in our patient is marked thrombocytopenia. Mild thrombocytopenia is common among classical infectious mononucleosis.9 However, severe thrombocytopenia is rare.10 Immune related destruction has been postulated. Autoantibodies to platelet glycoproteins GPIIb/IIIa and GPIb/IX on platelets and in plasma have been reported in a patient with infectious mononucleosis.11

Currently, there is no approved treatment for hMPV. Ribavirin has been demonstrated to be effective in mice,12 and it has been tried in a post heart–lung transplant patient with hMPV infection.13 Since it can cause serious life-threatening illness, another safer antiviral drug against this disease is urgently needed.

This is the first case report clearly documenting the ability of hMPV to cause MLI in an immunocompetent host, who can be prospectively followed from pre-symptomatic stage. Further studies will be required to identify the prevalence of hMPV-related MLI.

References

- 1.van den Hoogen B.G., de Jong J.C., Groen J., Kuiken T., de Groot R., Fouchier R.A. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719–724. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin G., De Serres G., Côté S., Gilca R., Abed Y., Rochette L. Human metapneumovirus infections in hospitalized children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:634–640. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn J.S. Epidemiology of human metapneumovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:546–557. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falsey A.R., Erdman D., Anderson L.J., Walsh E.E. Human metapneumovirus infections in young and elderly adults. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:785–790. doi: 10.1086/367901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng V.C., Wu A.K., Cheung C.H., Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Chan K.H. Outbreak of human metapneumovirus infection in psychiatric inpatients: implications for directly observed use of alcohol hand rub in prevention of nosocomial outbreaks. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boivin G., De Serres G., Hamelin M.E., Côté S., Argouin M., Tremblay G. An outbreak of severe respiratory tract infection due to human metapneumovirus in a long-term care facility. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1152–1158. doi: 10.1086/513204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurt C., Tammaro D. Diagnostic evaluation of mononucleosis-like illnesses. Am J Med. 2007;120:911. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.12.011. [e1–8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebihara T., Endo R., Kikuta H., Ishiguro N., Ishiko H., Hara M. Human metapneumovirus infection in Japanese children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:126–132. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.126-132.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter R.L. Platelet levels in infectious mononucleosis. Blood. 1965;25:817–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter R.B., Hong T.C., Bachli E.B. Life-threatening thrombocytopenia associated with acute Epstein–Barr virus infection in an older adult. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:672–675. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M., Kamijo T., Koike K., Ueno I., Nakazawa Y., Kurokawa Y. Specific autoantibodies to platelet glycoproteins in Epstein–Barr virus-associated immune thrombocytopenia. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:168–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02983388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamelin M.E., Prince G.A., Boivin G. Effect of ribavirin and glucocorticoid treatment in a mouse model of human metapneumovirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:774–777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.774-777.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raza K., Ismailjee S.B., Crespo M., Studer S.M., Sanghavi S., Paterson D.L. Successful outcome of human metapneumovirus (hMPV) pneumonia in a lung transplant recipient treated with intravenous ribavirin. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:862–864. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]