Abstract

We report on an anomalous X-ray reflectivity study to locate a labelled residue of a membrane protein with respect to the lipid bilayer. From such experiments, important constraints on the protein or peptide conformation can be derived. Specifically, our aim is to localize an iodine-labelled phenylalanine in the SARS E protein, incorporated in DMPC phospholipid bilayers, which are deposited in the form of thick multilamellar stacks on silicon surfaces. Here, we discuss the experimental aspects and the difficulties associated with the Fourier synthesis analysis that gives the electron density profile of the membranes.

Keywords: SARS E protein, Anomalous scattering, Lipid-peptide interaction

There is an increasing need in biomedical research for techniques capable of probing the structure and conformation of proteins and peptides in fluid lipid membranes such as viral ion channels and pharmaceutically relevant membrane proteins. The use of modern X-ray and neutron reflectivity techniques as tools to study biomimetic membranes is currently explored. These systems are composed of highly oriented lipid bilayers containing peptides or proteins, at controlled peptide-to-lipid ratios (P/L), which self-assemble on silicon surfaces, and can be swollen in water or water vapor [1]. We report the use of anomalous reflectivity [2] to gain structural sensitivity to a specific iodine-labelled phenylalanine residue in E protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. Just as in crystallography, the labelling of individual residues in combination with anomalous X-ray scattering can provide important structural constraints, e.g. to locate an individual amino acid with respect to the lipid bilayer. Here, we have used the well-known phospholipid model system dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospatidycholine (DMPC). The transmembrane part of the SARS E protein was synthesized by the Fmoc method [3], corresponding to the residues 7–38 of the protein [4]. Two different synthetic peptides were made: an unlabelled peptide and one containing iodine at position 23 (i.e., Phenylalanine) of the sequence. The lipid and peptide fractions were co-dissolved in organic solvent and deposited on pre-cut and cleaned silicon wafers by spreading the organic solution [5]. The procedure results in a very low membrane mosaicity, which is a prerequisite to apply X-ray reflectivity.

While we have previously determined the iodine position from the comparison of electron density profile of samples with unlabelled peptides to those of labelled peptides [3], [6], we investigate here whether one can obtain the same results on a single sample, by using several photon energies around an absorption edge of the iodine label. Note that it is also possible to draw conclusions from the comparison of two multilamellar samples with and without the label, but small differences in the two samples such as number N of bilayers and/or different defect densities may influence the achievable accuracy. Here, we explore whether anomalous reflectivity is a reasonable alternative. The anomalous dispersion effect near the absorption edge of an atom is accounted for by the complex atomic scattering factor expressed as , where q and E are the wavevector and the incident energy, respectively; corresponds to the scattering factor of the atom at energies sufficiently far from the absorption edge, and and are the real and the imaginary parts of the anomalous dispersion terms. These last two terms lead to a sensitivity of the reflectivity to the excited (resonant) atomic label. Differences in the reflectivity curves obtained at a set of energies then can be analyzed in terms of corresponding differences in the electron density profiles [7]. For example, measuring close to and far from the iodine edge at , yields a difference electron density profile for the iodine atom as .

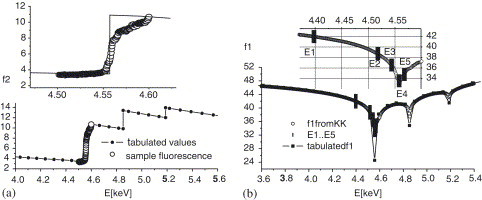

Experiments were carried out at the ID1 beamline of the European synchrotron radiation facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France. While scanning the photon energy around in steps of 0.5 eV by a double monochromator, the fluorescence spectrum of the sample was measured at fixed angle of illumination , using a silicon drift detector (X-flash, Roentec) with 150 eV energy resolution, which is positioned vertically above the sample. A fluorescence curve directly proportional to was obtained by defining the region of interest in the spectrum corresponding to the I fluorescence. This procedure using the sample, proved to be more practical than the absorption measurement of NaI solutions, which can also be used to determine the absorption coefficient , from which is obtained by the optical theorem [8]. In the present case, we scaled the measured curve of to the tabulated values [9], as shown in Fig. 1 (a) and combined it with the tabulated values to obtain a data set of higher precision at the absorption edge. The spectrum away from the absorption edge was normalized (absolute scale of electrons equivalents) to the standard tabulated values. The values were then extrapolated over the entire energy range. The real part which dominates the observed dispersion is then calculated from the usual Kramers–Kroning (KK) relation according to

| (1) |

where P in the front of the integral stands for ‘principal value’, which was carried out by numerical calculations (using a modified verion of a program kindly provided by T. Schülli). The resulting curve obtained from the KK integral is shown in Fig. 1(b) and exhibits a significant contrast of for the I edge. For the contrast variation measurement, the following five photon energies were chosen: , , , , and . It is apparent from Fig. 1 that the energies marked by and are optimal for the anomalous contrast, because the change in between these two points is largest, close to 8 electron equivalents. For the X-ray reflectivity measurements, the multilamellar stack was inserted in a closed temperature and humidity controlled chamber set to with an excess reservoir of saturated salt solution fixing the relative humidity (RH) to about 98%. The bilayers were swollen to a repeat distance of , less than expected for 98% RH. This means that the DMPC bilayer was partially hydrated. This limited swelling of solid-supported lipid films observation is well known as the so-called vapor-pressure paradoxon [10]. Note that full hydration in bulk samples is known to give . The sample was mounted on a standard Huber tower with the sample in the horizontal (xy) plane.

Fig. 1.

(a) edge fluorescence (open symbols) collected from a iodinated SARS E protein/DMPC sample as a function of X-ray energy, and scaled to the tabulated values of (line), shown over a small and larger E range. (b) The real part is obtained from imaginary part by Kramers–Kronig relation. Note that the computed curve (open circles) is more accurate than the tabulated values. From the curve, few photon energies are selected corresponding to different iodine contrast.

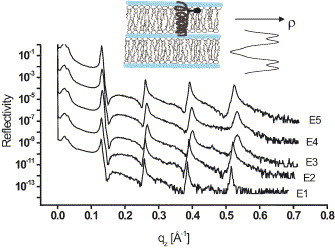

We first performed reflectivity experiments on a pure DMPC sample under the mentioned conditions as a test experiment and to check for radiation damage. No severe damage was observed despite the relatively high absorption coefficient at these energies. In the next step, we have measured a sample at . Fig. 2 shows the five reflectivity curves measured at – (shifted vertically for clarity), as a function of in order to suppress the effect of angular shifts due to the change in . The curves are characteristic of highly organized multilamellar films on solid supports. For pure DMPC, more than seven lamellar reflectivity peaks can be observed (not shown), but only four to five orders of reflection were observed in the presence of SARS E protein due to increased lamellar disorder. The periodicity (swelling state) was slightly drifting over the course of the experiment within . Since stability is a major concern in anomalous reflectivity, this should be improved in the next experiment by a better chamber design. Note, however, that changes in peak intensities and not positions are exploited below. To compare and analyze peak intensities, it is important to monitor the primary beam intensity with energy. For each energy step the monitor detector after the monochromator as well as before the sample are read out. In addition, primary beam profiles have been measured at each energy. Finally, the region of total external reflection (TER) also indicates the changes in , even though the TER plateau is affected also by anomalous effects.

Fig. 2.

X-ray reflectivity curves of iodinated SARS E protein/DMPC complex at and at five different X-ray energies. The curves have been shifted vertically for clarity. All curves exhibit the typical lamellar structure.

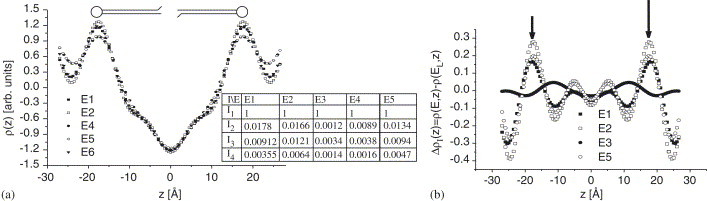

One of our goals is to achieve full range fits of each curve to determine . However, thermal fluctuations, lamellar disorder and resolution effects make this task difficult [11]. While such work is in progress, we apply here an empirical Fourier synthesis scheme, exploiting only the Bragg peak intensities, as it is often used for such multilamellar lipid membranes, e.g. see Ref. [12]. In simple terms the one-dimensional electron density profile normal to the interface is computed by Fourier coefficients (up to normalization constant) by

| (2) |

where the phases are reduced to positive/negative signs due to the mirror plane symmetry of the bilayer. Note that the maximum Bragg peak intensities have been corrected by an empirical Lorentz-like correction factor to calculate the th Fourier coefficient as . Here, we have used maximum peak intensities rather than integrated peak intensities. While often used in the literature, we do not actually believe that a Lorentz factor can account for all effects of absorption and illumination in the reflectivity experiment. Furthermore, fluctuation effects are not included in this treatment. Nevertheless—with all due caution—the profiles generated by Fourier synthesis should indicate the relative changes in the lamellar unit cell due to the resonant label. The results for are shown in Fig. 3 (a). The signs of the four Bragg peaks phases have been chosen as according to our previous results [3]. The Bragg peak intensities were all normalized to the first Bragg peak of each energy, since a comparison of the absolute Bragg intensities turned out to be difficult, e.g. due to the changes in absorption. A second reason is the strong decrease in the incident flux of more than an order of magnitude, e.g. when comparing the to the curve. Therefore, the curves shown here are relative density profiles. The usual interpretation of the profiles is as follows: the two main peaks in on both sides of the profile correspond to the phospholipid headgroups, the two sides minima to the water layer, and the central minimum is the terminal methyl moiety of the hydrocarbon chains. Fig. 3b shows the difference density profiles, calculated for each energy E by . From the maxima in these curves, one can deduce the most likely position of the iodine in the headgroup region at from the bilayer center, which is in agreement (within the estimated experimental error) with our previous determination [3]. This implies that the iodine labelled phenylalanine is positioned nearby the interface between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic part of the membrane. This finding has important implications for the structural modelling. As discussed in Ref. [3], the label position confirms a hairpin conformation adopted by the peptide which may play a role in the budding process of the viruses. However, we are facing a problem: the difference curves do not quantitatively scale according to the respective differences in . Furthermore, the curve which has a strong contrast only in shows strong maxima also in the profile. Finally, the profile shows two small and broad oscillations, which are shifted with respect to the other curves. However, we attribute relative changes smaller than 10% to experimental errors rather than a true effect. In our eyes the two main maxima of the difference curves are the only robust result.

Fig. 3.

(a) The electron density profiles as calculated from Fourier synthesis method at each energy, using the maximum Bragg peak intensities of the data in Fig. 2. The normalization procedure is described in the text. (b) The difference electron profiles, indicating the iodine positions (arrows).

Therefore, we conclude that: while pointing to nearly the same position of the label which was determined in a previous (non-resonant) experiment, the Fourier synthesis analysis did not give complete consistent results for the difference electron profiles for the present data set. One might wonder whether this problem can be solved by use of full range fitting of the reflectivity curves, which will be the next step. Apart from all systematic errors associated with the Fourier synthesis method, systematic inconsistencies may also result from sample drift, which was in the range of . Furthermore, since the anomalous effects expected for a single-atom label are small, the multilamellar reflectivity curves have to be measured with highest precision possible, and with an accurate measurement of the primary beam intensity. In the future, we intend to use oligo bilayer stacks also for anomalous reflectivity, which are composed of only a few membranes since full -range fits are easier to achieve in this case [13] and the number of bilayers N is a better controlled quantity. Moreover, absorption effects are not so strong for thin samples. Finally, angle dependent iodine fluorescence may also shed some light on the label position. In the present case with very thick stacks, no standing wave effects were observed, and the fluorescence yield remained constant when scanning the Bragg peaks.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the DFG through the German–Israel–Palestine trilateral Project SA 7772/6-1 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the team of ESRF/ID1 for the continuous help during the experiment and T. Schülli for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Salditt T. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 2003;13:467. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaknin D., Krueger P., Lösche M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:81021. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.178102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbely A., Khattari Z., Brotons G., Akkawi M., Salditt T., Arkin I.T. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:769. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marra M.A. Science. 2003;300:1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.20 mg/ml solutions of DMPC (Avanit Polar Lipids, AL) in chloroforme:HFI (1:1, v/v) and 2 mg/ml solutions of SARS E peptides in chloroforme:HFI (40%:60%, v/v) were mixed to the desired molar ratio at constant lipid concentration of (5 mg/ml) lipid solution. A drop of was then spread on cleaned and well leveled Silicon (1 0 0) substrates yielding an average stack thickness of about –. After slow evaporation the samples were kept in vacuum for several hours before rehydration from water vapor.

- 6.Z. Khattari, G. Brotons, I.T. Arkin, T. Salditt, in preparation.

- 7.Richardsen R., Vierl U., Cevc G., Fenzl W. Europhys. Lett. 1996;34:543. [Google Scholar]

- 8.J. Als-Nielsen, D. McMorrow, Elements of Modern X-ray Physics, New York, 2001.

- 9.D.T. Cromer, D. Liberman, Report LA-4403, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, 1970.

- 10.Podgornik R., Parsegian V.A. Biophys. J. 1997;75:942. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78728-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salditt T., Li C., Spaar A., Mennicke U. Eur. Phys. J. E. 2002;7:7105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C., Constantin D., Salditt T. J. Phys. Condens. Mater. 2004;16:2439. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mennicke U., Salditt T. Langmuir. 2002;18:8172. [Google Scholar]