Abstract

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) produces infectious bronchitis (IB) disease in poultry worldwide. In spite of proper vaccinations against the IBV, new IBV strains are continually emerging worldwide. In this study, a new highly virulent nephropathogenic IBV strain named CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 was identified from a vaccinated flock with clinical signs of IB in the Jiangsu province of China. The full-length genome sequence of the isolate was 27,714 nucleotides long, and the genome was organized similarly to classical IBV strains. Minimum divergence, phylogenetic analysis, and distance matrix of the genome showed that the CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate had the highest similarity to the IBV BJ strain. The spike glycoprotein (S) gene had the greatest similarity to the nephropathogenic BJ strain and showed an 8 amino acid insertion (YSNGNSDV) at 73 to 80 sites and 3 amino acid deletion at sites 126 to 128 compared to the IBV vaccine strains. A recombination analysis of the S gene showed that the new isolate evolved from the IBV BJ strain and the KM91 vaccine strain. An animal challenge experiment showed a mortality of 60 to 80% in early-age chickens by different inoculation routes. Pathological examinations of the kidneys revealed inflammation, distention with uric acid deposits, and tubular degeneration. It indicated that the CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate has robust kidney tissue tropism, and new nephropathogenic IBV strains are continuously evolving in China.

Key words: infectious bronchitis virus, genome, recombination, pathogenicity

INTRODUCTION

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is the causative agent of infectious bronchitis (IB) in chickens. It is clinically characterized by respiratory distress, tracheal rales, decreased feed intake, and poor egg quality and quantity (Cook et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012). In 1931, Schalk and Hawn first identified the respiratory disease of chicken in America; and in 1936 the virus was identified as the causative agent of infectious bronchitis (Cook, Jackwood and Jones, 2012).

IBV is a member of the family Coronaviridea, order Nidoviridae, and belongs to Gamma-coronavirus group 3 (Gonzalez et al., 2003; Zaher and Girh, 2014). The virus particle is enveloped, and has positive sense with single-strand RNA of approximately 27.6 Kb. The full-length genome consists of about 10 open reading frames (ORFs) (Liu et al., 2009b).

The proximal two-thirds of the genome encode 2 overlapping ORFs 1a and 1b. The remaining one-third genome consists of 4 structural proteins, spike glycoprotein (S), envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleocapsid protein (N) (Cavanagh, 2007; Li et al., 2013). The S glycoprotein is cleaved into S1 and S2 sub-units. The S1 gene is involved in attachment to the host cell receptors, transferring viral genome, neutralizing, and haemagglutination inhibition of antibodies (Liu et al., 2006b; Cavanagh, 2007; Liu et al., 2008).

New IBV isolates have been identified by diversity and evolutionary changes in the amino acids (aa) (Jia et al., 1995; Abro et al., 2012a; Hussein et al., 2014; Najafi et al., 2016; Seger et al., 2016). In China, the first IBV isolate was identified in 1982, and several later IB outbreaks have been reported in spite of proper vaccinations (Liu et al., 2006b; Liu et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2012; Afifi et al., 2015). Consequently, new IBV QX and LX4 genotypes have been identified (Liu et al., 2009b; Zeshan et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010b; Zou et al., 2010b; Zhou et al., 2014b). Therefore, there is a need for surveillance of recently circulating IBV strains showing genetic, antigenic, and virulence diversity.

In this study, we reported a novel IBV strain, named CK/CH/XDC-2/2013, which was isolated from a vaccinated chicken flock. In order to test a possible relationship between genetic variation and pathogenicity in chickens, the isolate was sequenced and analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus Isolation

The IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain was isolated from a chicken flock from Jiangsu province of China in 2013 by using 10-day-old specific pathogen free (SPF) chicken embryonated eggs (Nanjing Tech-Bank Bio-Industry Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China). The dead embryos had shown IBV like lesions, and their allantoic fluids were collected, titration calculated, and stored at −70°C.

Genomic Sequence

The viral RNA was extracted from the IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with oligodeoxynucleotide primers (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). A total of 21 fragments, covering the whole genome, were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA Polymerase (Stratagene Corp., La Jolla, CA). All primers used for PCR amplification were designed based on the IBV A2 strain (GenBank accession number EU526388) shown in Table 1 . Race PCR was performed using the 5-full race kit (TaKaRa, Shuzo, Japan), adopting primers and protocol described previously (Zhao et al., 2013). All amplified fragments were cloned into the pEASY-Blunt cloning vector (Beijing TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The full-length genome sequence of the viral strain was assembled from the acquired fragments using the Primer Premier Version 5.0 software program (Premier Biosoft International, 3786 Corina Way, Palo Alto, CA), Nucleotide Blast (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and the ORF finder program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html).

Table 1.

Primers designed for the amplification of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 full-length genome.

| Sr:# | Length/bp | Location | Upstream primers | Downstream primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1041 | 437-1478 | ATACGACGTTTGTAGGGG | GTGTTAAGTCATTTCGCATGC |

| 02 | 1426 | 1397-2823 | CAAGGTACTAAAGGTTTTGA | TTACCGTTCTTATCAACAAGT |

| 03 | 1462 | 2723-4185 | GCTGTGATCTACGAGAAAATG | GTAAAAACCTGCCCAAATTGA |

| 04 | 1383 | 4105-5488 | TCTTACAGAGGATGGTGTTAA | CCATAAGCCCATAGTAACACC |

| 05 | 1420 | 5405-6825 | TTGCGAATTCCCACCTTCTGG | CAAAGACATTGCGCATAATA |

| 06 | 1433 | 6757-8190 | TAATACACACAGTGCGCATGC | ACTAAACAAAAGTTCTCTAAC |

| 07 | 1434 | 8106-9540 | TTCCCAATGGGTTTTGTTTAA | ACTCTCCTTGACACTAATAAT |

| 08 | 1440 | 9469-10909 | CAACCTGACAAATTAGTTACT | AATATTCACTTAAATCAATAG |

| 09 | 1446 | 10788-12234 | TCTTGTTGAGTTACACAATAA | CTTTCTCCGTAGTAGGTATTT |

| 10 | 1431 | 12164-13595 | AAGTGCAGGAAATTTAGATG | CTGTCTGGTGTGTTATACCAG |

| 11 | 1453 | 13519-14972 | TTCTAACAATTTAGTTGATCT | CAAGCGGATATGCATCTATGG |

| 12 | 1417 | 14931-16348 | GACAGAGCCTGTGGCTGTTAT | AACATATTGGTAATTTATCTT |

| 13 | 1484 | 16273-17757 | GTTGGTAGACGAGGTTAGTAT | GAGCATGGCCGTGCACATTAC |

| 14 | 1451 | 17661-19112 | GTTTATAATCCACTTTTAGTG | ACGAGGTTCAAAAGTTTCATA |

| 15 | 1443 | 19007-20450 | AGATGGAGCGAACCTGTATGT | AGCACTACATAGTGCAAACA |

| 16 | 1466 | 20336-21802 | ACTGAACAAAAAACCGACTT | AACCCTCCAGCTGCTAAATAA |

| 17 | 1396 | 21782-23178 | GCAGAACTGGCCGAGGTTTTA | CATGTCTTCCACTACCACAAA |

| 18 | 1530 | 23100-24630 | GAATTAGCCACTCAAAAAATT | ATGCGGTTATAAATAGATTAT |

| 19 | 1435 | 24506-25941 | CCGAAGAACGGTTGGAATAA | CAAGTTTTCCCTTGGAATACT |

| 20 | 1446 | 25869-27315 | ACTTTCTTAACAAAGCAGGAC | AAACTGCAACCAACAAGGGA |

| 21 | 1005 | 26701-27706 | ATTCAGCACTTGGTGAAAATGA | TTTGCTCTAACTCTATACTAGC |

| 5′ RACE PCR PRIMERS | |

|---|---|

| TR1a | CTCCCAGATTACGGTCAAAC |

| A1b | GTGATTTGTGGTGGTCTTGGAC |

| A2b | CGGTTTCTGTAAGGGCTAGTTGA |

| R1c | AGTGGAGTCCCCAACAAACC |

| R2c | GCGACTACGAAAGCGAAAA |

Primers position is listed according to A2 strain, Accession number (EU526388).

= 5′ Phosphate primer used to amplify 5′RACE.

b = 5′ RACE primer 1.

= 5′ RACE primer 2.

Sequence Alignment and Pairwise Comparisons

The full-length genome nucleotide sequence of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 was aligned and analyzed for nucleotide homology and divergence percentage (Table 2 ) using the MegAlign 6 and DNASTAR software programs (Madison, WI).

Table 2.

Representative IBV strains used in this study.

| Year of |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access: Numbers | IBV strains | Pathogenesis | Country | isolation |

| KC119407 | Ck/CH/LGD/120724 | N/A | China | 2012 |

| JX897900 | GX-NN09032 | Resp/Nephro | China | 2012 |

| JX840411 | YX10 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2010 |

| HQ018914 | CK/CH/SC/MS10 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2010 |

| KF411041 | CK/CH/LGX/091109 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2009 |

| HM194666 | ck/CH/LHLJ/090712 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2009 |

| JF732903 | Sczy3 | Respiratory | China | 2009 |

| HQ018896 | CK/CH/GD/LZ09 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2009 |

| KF853202 | SDZB0808 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2008 |

| EU637854 | CK/CH/LSD/05I | Respiratory | China | 2008 |

| EU526388 | A2 | Respiratory | China | 2008 |

| HM245923 | DY07 | Respiratory | China | 2007 |

| FJ345395 | ck/CH/LSD/07-4 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2007 |

| FJ345364 | CK/CH/LDL/07I | Nephropathogenic | China | 2007 |

| JQ764826 | GX-YL9 | Respiratory | China | 2007 |

| HQ848267 | GX-YL5 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2005 |

| JF893452 | YN | Resp/Nephro | China | 2005 |

| DQ001338 | EP3 | Respiratory | China | 2005 |

| JQ764818 | GX-NN6 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2005 |

| DQ288927 | SAIBK | Nephropathogenic | China | 2005 |

| AY842862 | W93 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2004 |

| AY846750 | 28/86 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2004 |

| HM245924 | CQ04-1 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2004 |

| AY319651 | BJ | Nephropathogenic | China | 2003 |

| EU714029 | SC021202 | Nephropathogenic | China | 2002 |

| AF352313 | ZJ791 | Proventriculitis | China | 2001 |

| DQ068701 | CK/CH/LDL/97I/97 | Proventriculitis | China | 1997 |

| AY561713 | Ma5 | Nephropathogenic | USA | 2004 |

| AY514485 | California 99 | Respiratory | USA | 1999 |

| AF027512 | Florida-18288 | Respiratory | USA | 1972 |

| GU393338 | JMK | Respiratory | USA | 1964 |

| GU393334 | Gray | Nephropathogenic | USA | 1960 |

| KF696629 | Connecticut | Respiratory | USA | N/A |

| DQ834384 | M41 | Respiratory | USA | 1956 |

| GU393336 | Holte | Nephropathogenic | USA | 1954 |

| GQ504724 | Massachusetts | Respiratory | USA | 1941 |

| DQ646405 | TW2575/98 | Nephropathogenic | Taiwan | 1998 |

| DQ646406 | TW1171/92 | Nephropathogenic | Taiwan | 1992 |

| AF250006 | A1211 | Respiratory | Taiwan | 1992 |

| EU817497 | H52 | Respiratory | Netherland | 1955 |

| FJ807652 | H120 | Respiratory | Netherland | 1955 |

| JQ088078 | CK/SWE/0658946/10 | Reproductive | Sweden | 2010 |

| KF377577 | 4/91 | Respiratory | UK | 1991 |

| JQ977698 | KM91 | Nephropathogenic | South Korea | 1991 |

| DQ001339 | p65 | Respiratory | Singapore | 2005 |

| DQ490221 | Vic | Nephropathogenic | Australia | 2006 |

N/A - date not available

Phylogenetic Analyses, Selection Pressure and Recombination Analyses

Phylogenetic analysis of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 was performed using MEGA version 6 (Tamura et al., 2013). The sequence of 46 IBV strains was downloaded from GenBank (Table 2). The 25 IBV full-length genome, S gene, E gene, M gene, and N gene sequences, and 46 S1 partial genome sequence were used for phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses using the Neighbor–Joining method and Kimura-2 parameter method with bootstraps (1,000 replicates).

To assess the selective pressure on the spike gene, a codon based Morkov model of substitution was applied by using the PAML package (ver.14) (Yang et al., 2000). The calculations were performed by using synonymous (dS) and non-synonymous (dNS) substitutional differences among the codons to estimate the substitution rate.

To analyze the recombination events in spike glycoprotein, IBV spike gene sequences were aligned pairwise using the MegAlign program, DNASTAR software (version 6, Madison, WI). The recombination events were confirmed using the Recombination Detection Program (RDP V.3.44) (Martin and Rybicki, 2000; Posada and Crandall, 2001), at the highest P-value as 0.05.

Animal Challenge Experiment

Eighty one-day-old SPF chickens of white leghorns (Nanjing Tech-Bank Bio-Industry Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China) were randomly divided into 4 groups with 20 chickens per group. Groups A, B, and C were inoculated with 100 μl allantoic fluid containing 103 EID50 of IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 per chicken by oral, ocular, and nasal routes, respectively. Group D was inoculated with PBS orally as a control. The animals were kept in cages and provided food and water ad libitum. The chicks were observed daily for 15 d for clinical signs, morbidity, and mortality rates. Dead chickens were examined for gross and histopathological lesions, and the lung and kidney tissues were preserved in 4% buffered formalin. These samples were routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University (permit number IACECNAU20130905).

RESULTS

Comparison of Full-length Genomic Sequence of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013

The full-length genome sequence of IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain was submitted to GenBank under accession number KM213963. The sequence was 27,714 nt in length, excluding the poly (A) tails, including: 529 nt for the 5′ UTR, 11,918 nt for ORF1ab, 7,958 nt for ORF1b, 3,509 nt for the S structural gene (1,651 nt for S1 and 1,658 nt for S2), 173 nt for ORF3a, 188 nt for ORF3b, 308 nt for E gene, 677 nt for M gene, 197 nt for ORF5a, 248 nt for ORF5b, 1223 nt for the N gene, and 508 nt for the 3′ UTR, while, a non-coding region of 364 nt was identified in between the M gene and ORF5a.

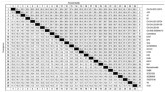

The genome sequence analysis of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 showed high identities (86.6%) of the spike (S) glycoprotein (S1 = 85.7 and S2 = 91.7%) with nephropathogenic IBV BJ strains (Table 3 ). All genes and 5′ end and 3′ end compared nucleotide similarity indices are summarized in Table 3. The CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain full-length genome pair wise nucleotide similarity was closely related to BJ and A2 strains (92.2 and 91.9%, respectively). In contrast, maximum divergence (16.6 and 16.4%, respectively) was found with H52 and H120 vaccine strain (Table 4 ).

Table 3.

Pairwise comparison of nucleotide homology of different ORFs between CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 and other IBV strains (%).

| IBV Strains | Full-length genome | 5′UTR | 1ab | 1b | S | S1 | S2 | 3a | 3b | E | M | 5a | 5b | N | 3′UTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YX10 | 88.9 | 96.2 | 45.4 | 93.8 | 80.1 | 72.9 | 88.3 | 87.9 | 78.3 | 98.2 | 95 | 83.9 | 93.6 | 83.9 | 98.6 |

| Connecticut | 85.1 | 93.1 | 73.6 | 88.9 | 81.9 | 38.8 | 86 | 85.1 | 78.8 | 85.7 | 96.1 | 87.6 | 91.6 | 86.5 | 82.6 |

| H52 | 84.5 | 94.3 | 67.4 | 88.7 | 37 | 74 | 85.3 | 81 | 79 | 89.5 | 90.9 | 88.2 | 90.4 | 88.8 | 97.9 |

| SDZB0808 | 89.3 | 95.3 | 44.7 | 93.8 | 81.3 | 73.1 | 88.4 | 88.5 | 78.3 | 99.1 | 35.3 | 83.9 | 94.8 | 92.8 | 95.9 |

| CK/CH/LSD/05I | 85.7 | 93.6 | 44.1 | 89.6 | 79.5 | 76.7 | 85.8 | 80 | 68.8 | 85.6 | 97.2 | 87.1 | 91.6 | 86.5 | 90 |

| BJ | 92.2 | 99.4 | 44.7 | 94.4 | 86.6 | 84.7 | 91.7 | 89.1 | 78.2 | 92.9 | 92.1 | 93.6 | 87.6 | 95.6 | 90.6 |

| Gray | 84.5 | 94 | 45 | 88.7 | 79.3 | 68.8 | 85.5 | 88.5 | 76.9 | 89.5 | 89.9 | 87.6 | 90 | 90 | 82.2 |

| DY07 | 89.5 | 94.7 | 43.5 | 93.9 | 81.5 | 73.2 | 88.5 | 87.9 | 78.3 | 99.1 | 95.1 | 87.1 | 96.8 | 93.2 | 97.9 |

| GX-YL5 | 89 | 96 | 45.9 | 94 | 84.7 | 81.7 | 87.4 | 96 | 89.5 | 94.6 | 95.1 | 89.7 | 92.4 | 82.9 | 97.4 |

| H120 | 84.6 | 94.2 | 67.2 | 89 | 36.6 | 73.9 | 85 | 81.6 | 78.5 | 88.6 | 95.7 | 88.8 | 91.6 | 88.8 | 76.8 |

| Holte | 83.9 | 93.8 | 74.2 | 89.1 | 78.5 | 69.6 | 85.5 | 82.7 | 75.8 | 90.1 | 90 | 92.9 | 91.2 | 90.3 | 69 |

| EP3 | 84.9 | 92.9 | 44 | 88.8 | 36 | 74.6 | 86.6 | 78.4 | 78.5 | 89.8 | 97.2 | 88.4 | 90.8 | 83.8 | 83.9 |

| KM91 | 85.4 | 93.8 | 75.1 | 89.7 | 80.3 | 77.8 | 88.6 | 81.9 | 86.6 | 90.9 | 91.9 | 86 | 90 | 91.1 | 91.7 |

| M41 | 84.5 | 93.7 | 54.4 | 88.6 | 79.9 | 38.4 | 85.4 | 76.6 | 79 | 88.9 | 94.9 | 84.2 | 90.4 | 91.1 | 97.4 |

| Massachusetts | 84.7 | 93.8 | 54.4 | 88.6 | 80 | 38.9 | 85.4 | 76.6 | 79 | 89.2 | 94.9 | 84.2 | 90.4 | 90.9 | 96.8 |

| SC021202 | 86.2 | 92.9 | 44.5 | 90.3 | 83.2 | 81.5 | 87.3 | 88.5 | 79.8 | 87 | 93.3 | 84.6 | 91.2 | 88.4 | 96.3 |

| TW2575/98 | 85.5 | 95 | 81.4 | 89.3 | 77.7 | 70.6 | 84.1 | 86.2 | 80.2 | 90.7 | 96.6 | 82 | 90.4 | 97 | 90.4 |

| YN | 86.3 | 94.5 | 44.3 | 90.2 | 83 | 81.9 | 87.3 | 91.6 | 75.1 | 79.7 | 92.7 | 84 | 91.2 | 86.1 | 96.3 |

| CK/CH/LGX/091109 | 89.1 | 95.8 | 47 | 94 | 85.8 | 82.5 | 88.4 | 87.9 | 77.7 | 100 | 93.5 | 84 | 96 | 93.8 | 97.2 |

| Ck/CH/LGD/120724 | 88.9 | 95.9 | 44.6 | 93.8 | 84.5 | 81.5 | 87.4 | 95.4 | 87.7 | 91.4 | 90.1 | 88.4 | 95.6 | 89 | 97.1 |

| CK/SWE/0658946/10 | 84 | 94.4 | 45.9 | 90.1 | 79.7 | 72.5 | 87.4 | 87.2 | 66.1 | 82.4 | 94 | 88.5 | 88 | 89.2 | 84.9 |

| 4/91 | 84.7 | 91.9 | 42.9 | 88.2 | 78.5 | 73.2 | 84.4 | 76.9 | 76.9 | 84.4 | 95 | 91.7 | 91.2 | 89.8 | 86.2 |

| A2 | 91.9 | 99.6 | 47.7 | 94.8 | 86 | 73.3 | 88.3 | 88.5 | 66.4 | 92.5 | 94.9 | 85.2 | 96.8 | 92 | 95.6 |

| SAIBK | 85.4 | 91.4 | 47.2 | 89.3 | 83.3 | 81.3 | 87.8 | 87.4 | 76.1 | 88.7 | 95.2 | 86.5 | 92 | 84.9 | 97.3 |

| GX-NN09032 | 86.1 | 96.2 | 46.8 | 93.7 | 73.8 | 63.4 | 75.4 | 86 | 83.4 | 87.1 | 93.2 | 82.1 | 90.8 | 81.3 | 92.2 |

Pairwise highest nucleotide homology is presented in bold numbers, and lowest nucleotide homology is underlined.

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of full-length genome sequence of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 divergence distance with other IBV strains.

|

The deduced amino acid sequence of the S gene when compared with the H120, H52, and Ma5 vaccine strains showed that the new strain had an insertion of 8 aa (YSNGNSDV) from position 73 to 80 and a deletion of 3 aa at position 126 to 128 (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Alignment of spike glycoprotein of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain with several representative vaccine strains. The aa insertion and deletion are indicated by boxes.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the complete genome, and of the S, S1, E, M, and N genes of IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 (Figure 2 ). This indicated that the CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 strain was closely related to the Chinese strains BJ and A2 based on the full-length genome, and S, M, and N genes. However, the phylogenetic tree of the partial S1 gene indicated that the IBV isolates were distributed into 5 clusters (Figure 2c). CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 belongs to the second group with BJ and A2 strains.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis based on IBV strains nucleotide sequences of the full-length genome (a), S (b), S1 (c), E (d), M (e), and N (f) genes. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method; bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) and Kimura-2 parameter method conducted in MEGA6. The bar represents the genetic distance of 0.01.

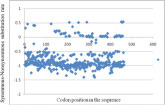

Analysis of Selection Pressure

The spike glycoprotein pairwise comparison results showed that most of the S1 sub-unit had positive codon selection of non-synonymous amino acid substitutions at specific regions encompassing positions 141 to 210, 236 to 303, 254 to 378, and 421 to 452. In contrast, most codon regions of the S2 sub-unit were highly conserved at regions 452 to 460 (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

The selective pressure in S gene of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate illustrated that S glycoprotein gene has negative selective pressure emphasis on non-synonymous aa substitutions.

Recombination Analyses

The recombination hot spots of the complete S protein gene sequence of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 were analyzed by the recombination detection program (RDP). The results showed true recombination between BJ (major parent) and KM91 (minor parent) with the break point at nucleotide position 2341 and the end point at nucleotide position 2566, using RDP, Geneconv, Chimaera, MaxChi, Bootscan, Siscan, and 3Seq analyses with average P-values of 1.040 × 10−07, 7.686 × 10−06, 3.637 × 10−01, 2.358 × 10−02, 1.070 × 10−07, 5.068 × 10−06 and 1.070 × 10−07, respectively (Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

The recombinant event of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 was analyzed by RDP (a) and MaxChi (b) analyses. The pink region displayed the potential recombination site; the yellow line indicates the percentage identity between the minor parent (KM91) and major parent (BJ). The green line shows the percentage identity between the major parent (BJ) and recombinant (CK/CH/XDC-2/2013). The variable size per window of RDP and MaxChi were selected at 30 and 70.

Pathogenicity of the Isolate in Chickens

The infected chickens showed the earliest clinical signs 2 d after inoculation, and died between 4 and 6 days. The clinical manifestations included depression, decrease in feed intake, and ruffled feather with rapid body weight loss. The morbidity and mortality were more than 75 and 60% respectively (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Comparison of the morbidity and mortality of chickens challenged with different inoculation routes.

| Number of |

Morbidity |

Mortality |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | chickens | rate (%) | rate (%) |

| A | 20 | 85 | 75 |

| B | 20 | 80 | 80 |

| C | 20 | 75 | 60 |

| D | 20 | 00 | 00 |

Inoculation route, A = oral, B = eye, C = nasal, D = oral control.

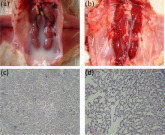

At necropsy, the chicken kidneys were prominently inflamed, and hyperemic renal tubules were distended with uric-acid crystal deposits (Figure 5 ). Histopathologically, there was hyperemia of the nephrons, accumulation of red blood cells, necrosis, and prominent monocytes infiltration in the epithelial cells (Figure 5). Meanwhile, no lesions were observed in the control group. In addition, IBV was detected in the kidneys and lungs from all infected chickens, using RT-PCR.

Figure 5.

Gross and histopathological kidney lesions of chicken, inflammation, hyperemia, and distension with uric-acid crystal deposits in the kidneys of chickens challenged with CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 (a), non-infected control group (b), kidney nephrons and tubules showed degeneration and distension (c), hyperemic vessels with monocytes infiltration and epithelial necrosis (d) (H&E staining, 400×)

DISCUSSION

Infectious bronchitis is the most important devastating disease of the poultry industry throughout the world. Many vaccines (W93, 28/86, H52, Ma5, and H120) are widely used, but they cannot provide complete protection against IBV infection (Liu and Kong, 2004).

In our study, we found a recombinant nephropathogenic IBV strain from an IBV-vaccinated chicken flock. The full-length genome sequence analyses of the IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate showed structural similarity (5′UTR-1ab+1b-S-3a+3b+E-M-5a+5b-N-3′UTR) to previously identified strains (Liu et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2010a). However, a non-coding region of an approximately 364 nt was identified as reported before (Liu et al., 2009a; Abro et al., 2012b). Phylogenetic analyses showed that the full-length genome and spike gene of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 were closely related to the nephropathogenic IBV BJ strain, the E gene was close to the nephropathogenic GX-YL5, and the S1 gene revealed its relation to LX4 type cluster (Liu and Kong, 2004), which was circulating in more than 50% IBV strains in China (Zou et al., 2010a; Han et al., 2011). In addition, no part of the full-length genome was similar in nucleotides identity with any available vaccines (H120, H52, Connecticut, and 4/91), indicating that CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 was relatively close to previously identified clusters of Chinese strains identified between 2000 and 2012 (Liu et al., 2009b; Zou et al., 2010a; Ji et al., 2011).

The spike glycoprotein gene always remains under pressure of mutational changes, and approximately 2 to 3% amino acid difference can decrease immune protection (Cavanagh, 2005). In this study, the S gene nucleotide identity of the CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate was more dissimilar (37 and 36.6%) than those of H120 and H52 vaccine strain, respectively. Furthermore, the spike gene had an 8 amino acid insertions at the 73 to 80 site near or within HVR1 position in the S1 gene, and a 3 amino acid deletion as compared to IBV vaccines strains.

Comparison of synonymous and non-synonymous substitution rates provides vital information related to mechanisms of DNA sequence evolution. In the present study, there was evidence for positive selection in the regions of the S1 sub-unit. In contrast, no evidence for positive selection was found in the S2 sub-unit. These selective constraints in the spike gene of IBV are in accordance with a previous report (Abro et al., 2012b).

The recombination events mostly occur naturally or mutationally in the IBV S gene (Wang et al., 1993). Here, the results showed that the S gene of CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 came from the recombination of the major parent BJ and minor parent KM91 strains, which suggested that more genotypic evolutionary and recombination events can occur under the pressure of widespread use of live attenuated IBV vaccines (Zhou et al., 2014a).

IBV isolates had been classified as nephropathogenic or respiratory, depending on clinical manifestations and lesions. Thus, gross and histopathological kidney lesions and mortality were used to assess nephropathogenicity (Chong and Apostolov, 1982; Ignjatović and Sapats, 2000; Ignjatovic et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2006a; Zaher and Girh, 2014). In this study, the chicken challenge experiment showed high morbidity (85%) and mortality (80%) in one-day-old chickens, with similar clinical signs to field outbreak. All virus challenged chickens did not show prominent respiratory infection signs, such as sneezing, gasping, or coughing. At necropsy, there was no presence of pus or mucous clogging visually at the bronchi bifurcation region or in the trachea, as described (Grgiæ et al., 2008). The kidneys were highly inflamed and distended with uric acids deposits, indicating that this isolate had strong tropism to kidneys, as previously reported (Liu and Kong, 2004). Histopathological examination showed nephritis, necrosis, and monocytes infiltration in epithelial tissues in the kidneys, which were similar to previous reports (Benyeda et al., 2009). This demonstrated that this new isolated IBV strain belongs to high a nephropathogenic strain emerging from circulating field IBV strains.

CONCLUSION

The new IBV CK/CH/XDC-2/2013 isolate demonstrated characteristic features of nephropathogenic IBV in chickens. At necropsy, the chicken kidneys were prominently hyperemic, inflamed, and distended with uric-acid crystal deposits. The nucleotide sequence of the isolate showed recombination, insertions, and deletions in the spike gene, and apparent genetic variations in the ORFs regions of the genome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported mainly by the National Natural Science Foundation (31230071), grants from the Ministry of Education, China (20120097110043), and the priority academic program development of Jiangsu higher education institutions (PAPD). Authors are grateful to David Morrison, Uppsala University, Sweden, for editing the English language of this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RAL and PJ designed the study and wrote the manuscript. RAL isolated the virus, completed genome sequencing and animal experiments, and analyzed the data. JB and BF carried out the PCR analyses and histopathological examinations. HW and LZ helped in collecting the samples from the poultry flocks. SHA helped in the data analysis of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abro S.H., Renstrom L.H., Ullman K., Belak S., Baule C. Characterization and analysis of the full-length genome of a strain of the European QX-like genotype of infectious bronchitis virus. Arch. Virol. 2012;157:1211–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abro S.H., Renström L.H., Ullman K., Belák S., Baule C. Characterization and analysis of the full-length genome of a strain of the European QX-like genotype of infectious bronchitis virus. Arch. Virol. 2012;157:1211–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi M.A., Zaki M.M., Zoelfokkar S.A., Abo-Zeid H.H. Evaluation of spectrum of protection provided against two infectious bronchitis isolates using classical live vaccine. Life Sci. J. 2015:12. [Google Scholar]

- Benyeda Z., Mato T., Süveges T., Szabo E., Kardi V., Abonyi-Toth Z., Rusvai M., Palya V. Comparison of the pathogenicity of QX-like, M41 and 793/B infectious bronchitis strains from different pathological conditions. Avian Pathol. 2009;38:449–456. doi: 10.1080/03079450903349196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronaviruses with Special Emphasis on First Insights Concerning. SARS; Birkhauser Basel: 2005. Coronaviridae: A Review of Coronaviruses and Toroviruses; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Veterinary research. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong K., Apostolov K. The pathogenesis of nephritis in chickens induced by infectious bronchitis virus. J. Comp. Pathol. 1982;92:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(82)90078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.K., Jackwood M., Jones R.C. The long view: 40 years of infectious bronchitis research. Avian pathology: journal of the W.V.P.A. 2012;41:239–250. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.680432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J.M., Gomez-Puertas P., Cavanagh D., Gorbalenya A.E., Enjuanes L. A comparative sequence analysis to revise the current taxonomy of the family Coronaviridae. Arch. Virol. 2003;148:2207–2235. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grgiæ H., Hunter D.B., Hunton P., Nagy É. Pathogenicity of infectious bronchitis virus isolates from Ontario chickens. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2008;72:403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Sun C., Yan B., Zhang X., Wang Y., Li C., Zhang Q., Ma Y., Shao Y., Liu Q., Kong X., Liu S. A 15-year analysis of molecular epidemiology of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus in China. Infection, Genet. Evol. 2011;11:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein A.H., Emara M., Rohaim M., Ganapathy K., Arafa A. Sequence analysis of infectious bronchitis virus IS/1494 like strain isolated from broiler chicken co-infected with Newcastle disease virus in Egypt during 2012. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2014;13:530–536. [Google Scholar]

- Ignjatovic J., Ashton D., Reece R., Scott P., Hooper P. Pathogenicity of Australian strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus. J. Com. Pathol. 2002;126:115–123. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignjatovic J., Sapats S. Avian infectious bronchitis virus. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics) 2000;19:493–508. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.2.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J., Xie J., Chen F., Shu D., Zuo K., Xue C., Qin J., Li H., Bi Y., Ma J. Phylogenetic distribution and predominant genotype of the avian infectious bronchitis virus in China during 2008–2009. Virol J. 2011;8:184. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Karaca K., Parrish C.R., Naqi S.A. A novel variant of avian infectious bronchitis virus resulting from recombination among three different strains. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:259–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01309861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Mo M.L., Huang B.C., Fan W.S., Wei Z.J., Wei T.C., Li K.R., Wei P. Continuous evolution of avian infectious bronchitis virus resulting in different variants co-circulating in Southern China. Arch. Virol. 2013;158:1783–1786. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1656-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang X.Y., Wei P., Chen Q.Y., Wei Z.J., Mo M.L. Serotype and genotype diversity of infectious bronchitis viruses isolated during 1985–2008 in Guangxi, China. Arch.Virol. 2012;157:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Kong X. A new genotype of nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis virus circulating in vaccinated and non-vaccinated flocks in China. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:321–327. doi: 10.1080/0307945042000220697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Wang Y., Ma Y., Han Z., Zhang Q., Shao Y., Chen J., Kong X. Identification of a newly isolated avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus variant in China exhibiting affinity for the respiratory tract. Avian Dis. 2008;52:306–314. doi: 10.1637/8110-091307-ResNote.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Zhang Q., Chen J., Han Z., Liu X., Feng L., Shao Y., Rong J., Kong X., Tong G. Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus strains isolated in China between 1995 and 2004. Arch. Virol. 2006;151:1133–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0695-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.W., Zhang Q.X., Chen J.D., Han Z.X., Liu X., Feng L., Shao Y.H., Rong J.G., Kong X.G., Tong G.Z. Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus strains isolated in China between 1995 and 2004. Arch. Virol. 2006;151:1133–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0695-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-L., Su J.-L., Zhao J.-X., Zhang G.-Z. Complete genome sequence analysis of a predominant infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) strain in China. Virus Genes. 2009;38:56–65. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.L., Su J.L., Zhao J.X., Zhang G.Z. Complete genome sequence analysis of a predominant infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) strain in China. Virus Genes. 2009;38:56–65. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Shao Y., Sun C., Han Z., Liu X., Guo H., Liu X., Kong X., Liu S. Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus in recent years in China. Avian Dis. 2012;56:15–28. doi: 10.1637/9804-052011-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D., Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi H., Langeroudi A.G., Hashemzadeh M., Karimi V., Madadgar O., Ghafouri S.A., Maghsoudlo H., Farahani R.K. Molecular characterization of infectious bronchitis viruses isolated from broiler chicken farms in Iran, 2014–2015. Arch. Virol. 2016;161:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D., Crandall K.A. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: Computer simulations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:13757–13762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241370698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger W., Langeroudi A.G., Karimi V., Madadgar O., Marandi M.V., Hashemzadeh M. Genotyping of infectious bronchitis viruses from broiler farms in Iraq during 2014–2015. Arch. Virol. 2016;161:1229–1237. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2790-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Han Z., Ma H., Zhang Q., Yan B., Shao Y., Xu J., Kong X., Liu S. Phylogenetic analysis of infectious bronchitis coronaviruses newly isolated in China, and pathogenicity and evaluation of protection induced by Massachusetts serotype H120 vaccine against QX-like strains. Avian pathology: journal of the W.V.P.A. 2011;40:43–54. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.538037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular biology and evolution. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Junker D., Collisson E.W. Evidence of natural recombination within the S1 gene of infectious bronchitis virus. Virology. 1993;192:710–716. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Nielsen R., Goldman N., Pedersen A.M. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaher K.S., Girh Z.M.A. Concurrent infectious bronchitis and Newcastle disease infection in Egypt. Brit. J. Poul. Sci. 2014;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeshan B., Zhang L., Bai J., Wang X., Xu J., Jiang P. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a replication-defective infectious bronchitis virus vaccine using an adenovirus vector and administered in ovo. J. Virol. methods. 2010;166:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang H.-N., Wang T., Fan W.-Q., Zhang A.-Y., Wei K., Tian G.-B., Yang X. Complete genome sequence and recombination analysis of infectious bronchitis virus attenuated vaccine strain H120. Virus genes. 2010;41:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang H.N., Wang T., Fan W.Q., Zhang A.Y., Wei K., Tian G.B., Yang X. Complete genome sequence and recombination analysis of infectious bronchitis virus attenuated vaccine strain H120. Virus genes. 2010;41:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F., Zou N., Wang F., Guo M., Liu P., Wen X., Cao S., Huang Y. Analysis of a QX-like avian infectious bronchitis virus genome identified recombination in the region containing the ORF 5a, ORF 5b, and nucleocapsid protein gene sequences. Virus genes. 2013;46:454–464. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0884-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Tang M., Jiang Y., Chen X., Shen X., Li J., Dai Y., Zou J. Complete genome sequence of a novel infectious bronchitis virus strain circulating in China with a distinct S gene. Virus genes. 2014;49:152–156. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Tang M., Jiang Y., Chen X., Shen X., Li J., Dai Y., Zou J. Complete genome sequence of a novel infectious bronchitis virus strain circulating in China with a distinct S gene. Virus genes. 2014;49:152–156. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou N.-L., Zhao F.-F., Wang Y.-P., Liu P., Cao S.-J., Wen X.-T., Huang Y. Genetic analysis revealed LX4 genotype strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus became predominant in recent years in Sichuan area, China. Virus genes. 2010;41:202–209. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0500-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou N.L., Zhao F.F., Wang Y.P., Liu P., Cao S.J., Wen X.T., Huang Y. Genetic analysis revealed LX4 genotype strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus became predominant in recent years in Sichuan area, China. Virus genes. 2010;41:202–209. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0500-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]