Graphical abstract

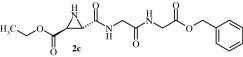

The inhibition of SARS-CoV main protease by the aziridinyl peptide 2c is described.

Keywords: SARS, Main protease, Inhibitor, Aziridine

Abstract

The coronavirus main protease, Mpro, is considered a major target for drugs suitable to combat coronavirus infections including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In this study, comprehensive HPLC- and FRET-substrate-based screenings of various electrophilic compounds were performed to identify potential Mpro inhibitors. The data revealed that the coronaviral main protease is inhibited by aziridine- and oxirane-2-carboxylates. Among the trans-configured aziridine-2,3-dicarboxylates the Gly-Gly-containing peptide 2c was found to be the most potent inhibitor.

Coronaviruses are important pathogens that mainly cause respiratory and enteric disease in humans, livestock, and domestic animals.1 In 2003, a previously unknown coronavirus called SARS-CoV was identified as the causative agent of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a newly emerging disease that within a few weeks spread from its likely origin in Guangdong Province, China, to neighboring regions and many other countries.2, 3, 4 Coronaviruses are plus-strand RNA viruses that use a complex enzymology to replicate the largest RNA genomes currently known and synthesize an extensive set of 5′ leader-containing subgenomic mRNAs that encode the viral structural proteins and several species-specific proteins with unknown functions.1, 5, 6 The enzymatic activities required for viral RNA synthesis are part of two virus-encoded polyproteins of about 450 and 750 kDa, respectively, that are extensively processed by two or three viral proteases to yield up to 16 mature proteins and multiple processing intermediates.7

Most of the cleavages are mediated by the coronavirus main protease, Mpro, a cysteine protease featuring a two-β-barrel structure (domains I and II) that is linked to a C-terminal α-helical domain III. The structure of domains I and II is similar to that of chymotrypsin-like serine proteases.7, 8, 9, 10 Because of its essential role in proteolytic processing, the Mpro is considered an attractive target for antiviral drugs against SARS and other coronavirus infections.9

Up to now, a number of potential inhibitors have been proposed employing molecular modeling and virtual screening techniques.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

However, the inhibitory potency of these compounds has not yet been verified.

Only a small number of potent protease inhibitors were identified by screening assays thus far.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Most of these studies used commercially available compound libraries for their screening assays. With the exception of a peptidyl chloromethylketone10 and recently published etacrynic acid derivatives25 none of the potent compounds identified up to date was developed and is predicted to target the active site cysteine residue. This lack of active-site directed lead structures motivated the search for new leads with proven active-site directed activity.

The scrutinized compounds contain electrophilic building blocks (aziridine,26, 27 epoxide,26, 28, 29, 30 see Table 1 ) which are known to react with nucleophilic amino acids within the active site of proteases. For example, trans-configured epoxysuccinyl-based peptides-like E-64, 1 30 and respective aziridines27 are highly active inhibitors of CAC131 cysteine protease. Their proposed inhibition mechanism is the alkylation of the active site cysteine residue. However, E-64 is reported to be inactive against coronaviral main proteases and 3C-like picornaviral proteases.32, 33, 34 cis-Configured epoxides, on the other hand, are known to inhibit aspartic proteases29 by alkylation of one aspartate residue within the active site, and α,β-epoxy ketones are reported to inhibit both serine and cysteine proteases, depending on the stereochemistry of the epoxide ring.28

Table 1.

Results of the screening of various protease inhibitors against SARS-CoV Mpro

| Compound | Configuration of the TMR | R1 | R2 | X | R3 | Inhibition of SARS-CoV Mproat 100 μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | rac-cis (S,S + R,R) | Phenyl | OMe | Bn-N | H | ni |

| 1b | rac-cis (S,S + R,R) | Me | OEt | Bn-N | H | ni |

| 1c (1/1)c | rac-cis (S,S + R,R) | Me | (S)-Phe-OBn | Bn-N | H | 34 ± 7a |

| 1d | cis (S,S) | Me | (S)-Phe-OBn | Bn-N | H | 24 ± 2a |

| 1e (1.1/1)c | rac-cis (S,S + R,R) | Phenyl | (S)-Phe-OBn | Bn-N | H | 30 ± 9a |

| 1f (1.4/1)c | rac-cis (S,S + R,R) | Phenyl | (S)-Val-OBn | Bn-N | H | 22 ± 2a |

| 2a | cis (R,S) | MeO2C | OMe | HN | H | ni |

| 2b | cis (R,S) | EtO2C | OEt | HN | H | ni |

| 2c | trans (S,S) | EtO2C | Gly-Gly-OBn | HN | H | 54 ± 5a/75 ± 7b(see also Ref. 37) |

| 2d | trans (S,S) | EtO2C | (S)-Ile-OBn | HN | H | ni |

| 3a | trans (S,S) | BnO2C | OBn | BOC-Gly-(S)-Pip-N | H | 29 ± 4a |

| 3b | trans (R,R) | EtO2C | OEt | BOC-(S)-Leu-(R + S)-Azet-N | H | 16 ± 4a |

| 3c | trans (R,R) | EtO2C | OEt | BOC-(S)-Leu-(S)-Pro-N | H | 16 ± 6a |

| 4a | (R + S) | H | OMe | MeO2C-CH2-N | H | 30 ± 6a |

| 4b | (R + S) | H | OMe | BnO2C-CH2-N | H | 26 ± 4a |

| 4c (1.1/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 30 ± 3a |

| 4d (1.5/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 20 ± 6a |

| 4e (1.1/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 28 ± 7a |

| 4f (1.2/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 34 ± 5a |

| 4g (2.3/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 30 ± 5a |

| 4h (1.2/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe | H | 39 ± 6a | |

| 4i (1.2/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 28 ± 3a |

| 4k (1.1/1)c | (R + S) | H | (S)-Phe-OMe | MeO2C-CH2-N | H | ni |

| 4l (1.3/1)c | (R + S) | H | OMe |  |

H | 48 ± 6a |

| 5a | (R + S) | Me | OMe | BOC-N | CO2Me | ni |

| 5b | (R + S) | Me | OMe | EOC-N | CO2Me | ni |

| 5c | (R + S) | Me | OMe | HN | CO2Me | ni |

| 6a | cis (R,R) | Me | OH | O | H | ni |

| 6b | cis (R,S) | MeO2C | OMe | O | H | ni |

| 6c | cis (R,S) | EtO2C | O | H | ni | |

| 6d | cis (R,R) | Me | (S)-Phe-OBn | O | H | 15 ± 5a |

| 6e | cis (R,R) | Me | (R)-Phe-OBn | O | H | ni |

| 6f | cis (S,S) | Me | (R)-Phe-OBn | O | H | ni |

| 6g | cis (S,S) | Me | (S)-Phe-OBn | O | H | 28 ± 6a |

| 6h | cis (S,S) | Me | (R)-Phe | O | H | ni |

| 6i | cis (R,R) | Me | (S)-Phe | O | H | ni |

| 6k | cis (R,R) | Me | (S)-Val-OBn | O | H | 10 ± 3a |

| 6l (1.2/1)c | rac-cis (R,S + S,R) | EtO2C | (S)-Phe-OBn | O | H | 22 ± 5a |

| 7a | cis (R,S) | For structure see above | ni | |||

All amino acids are abbreviated in the three-letter code; ni inhibition <10%; TMR three-membered ring.

Percentage inhibition as obtained in the FRET-based assay, values are mean values of at least 2 independent assays.

Percentage inhibition as obtained in the HPLC assay, mean value of four independent assays.

Ratio of diastereomers.

To investigate whether epoxides, and aziridines could serve as electrophilic building blocks for coronaviral main proteases, and to evaluate which stereochemistry will be preferred by these proteases, both, trans- and cis-configured differently substituted three-membered heterocycles, were included in the screening.

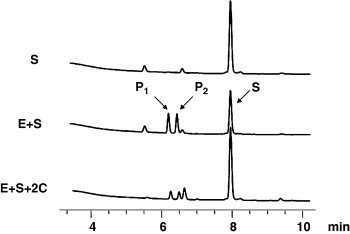

First, a screening was performed with an HPLC-based assay using VSVNSTLQ|SGLRKMA9, 34, 35 as substrate (Fig. 1 ). Second, the screening was extended using a less time-consuming and less intricate fluorimetric assay using a FRET-pair labeled substrate25 (Table 1). The screening revealed the trans-configured N-unsubstituted aziridine-2,3-dicarboxylate 2c (S,S)-(EtO)Azi-Gly-Gly-OBn,36 which showed 75% inhibition of SARS-CoV Mpro in the HPLC assay (Fig. 1) and 54% inhibition in the fluorimetric assay at 100 μM,37 and the aziridine-2-carboxylate 4l, which showed 48% inhibition, as most potent compounds (Table 1).

Figure 1.

HPLC profiles of proteolytic reactions for determination of enzymatic activity of SARS-CoV Mpro and of inhibition by 2c. S, substrate VSVNSTLQ|SGLRKMA; E, enzyme SARS-CoV Mpro; P, hydrolysis products VSVNSTLQ and SGLRKMA.

Within the series of trans-configured aziridines 2c, 2d, and 3a–3c, only the Gly derivative 2c shows considerable activity. Only weak activity is found for the derivatives-containing larger amino acids (2d, 3a–3c) which, in contrast, are good inhibitors of CAC1 proteases (e.g., inhibition of cathepsin L by 3a: K i = 6.4 μM and by 3b: K i = 4.8 μM).27

The study also revealed that epoxide or aziridine building blocks alone, which do not bear an amino acid moiety, are not active (1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, and 6a–6c). Within the series of cis-configured epoxides and aziridines weak inhibition is exhibited by the N-benzyl aziridines-(1c–1f) and the PheOBn-containing epoxides 6d, 6g, and 6l. The free acids (6h, 6i) are inactive. The diastereomeric mixture of PheOBn-containing N-benzyl aziridines 1c is slightly more active than the pure compound 1d, suggesting that the diastereomer with (R,R) configured aziridine ring is the more potent isomer. With the exception of 4k all aziridine-2-carboxylates (1c–1f, 4a–4i, 4l) are active in the range between 20 and 50%, whereas all aziridine-2,2-dicarboxylates (5a–5c) are inactive. Interestingly, epoxide 7a which is the only compound without an electron-withdrawing substituent at the three-membered ring does not show any activity.

These results show that in contrast to CAC1 proteases which are only inhibited by trans-configured three-membered heterocycles28, 30, 38 cis-configured analogues can serve as building blocks for inhibitors of PAC30 proteases as well.

To better understand the relevant interactions between the most potent inhibitor 2c and the SARS-CoV Mpro, docking experiments using FlexX™39 were carried out. The binding site was extracted from the recently published structure of the complex of SARS-CoV Mpro with a peptpeptidyl chloromethyl ketone (CMK) (PDB code: 1UK4).10

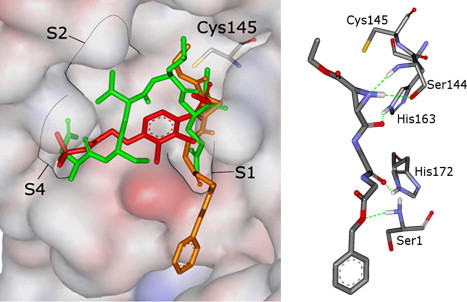

Figure 2 shows a docking overlay of the CMK (green), with the aziridinyl peptide 2c (orange) and the proposed binding mode of 2c.

Figure 2.

Docking overlay of hexapeptidyl CMK (green) and aziridinyl peptide 2c (orange) (left). Predicted H-bonds between 2c and SARS-CoV Mpro (right).

The substrate analogue hexapeptidyl chloromethyl ketone inhibitor (Cbz-Val-Asn-Ser-Thr-Leu-Gln-CMK) is shown as found after elimination of the covalent bond and subsequent minimization of the active site of the SARS-CoV Mpro.

The docking of the aziridine derivative 2c (orange) suggests that the reactive center of the compound is located in close proximity to the sulfur of Cys145 (co-crystallized ligand: 3.14 Å; 2c, 3.91 Å). The main part of 2c is located in the S1 pocket of the enzyme.

For this compound the interactions with the enzyme are described by hydrogen bonds to amino acids of the B-chain (Ser1) and A-chain (Ser144, His163, and His172) (Fig. 2) suggesting that 2c should better fit into the protein dimer which is formed in solution at high concentrations and which is supposed to be the active enzyme form.40 For the docked conformations, hydrophobic interactions are found for the terminal ethyl group only. This group is positioned in proximity to the S1′ pocket. In the docked conformations, the terminal benzyl residue is solvent exposed, suggesting that this group is not overly important for a high biological activity. Since neither the ethyl nor the benzyl groups show optimal fit into the enzyme, a number of possibilities for synthetical optimization are conceivable. These include enlargement of the ethyl group and replacement of the benzyl group by an amide group mimicking the side chain of Gln which is supposed to be the optimal residue for the S1 pocket. In this context, a modification of the peptidic nature of 2c into a peptidomimetic one has also to be kept in mind due to pharmacokinetic reasons.

In summary, a comprehensive screening of electrophilic compounds has revealed the trans-configured aziridine-2,3-dicarboxylate 2c as modest active-site directed SARS-CoV Mpro inhibitor with potential for further optimization. In addition, aziridine- and oxirane-2-carboxylic acid-containing compounds also show weak inhibitory activity. This activity might be enhanced when the electrophilic building blocks are linked to appropriate amino acids (e.g., Gln), substrate analogue peptides or peptidomimetics.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: Azet, azetidine-2-carboxylic acid; Cbz, benzoxycarbonyl; E-64 [[(2S,3S)-(epoxysuccinyl)-(S)-leucyl]amino]-4-guanidinobutane; EOC, ethoxycarbonyl; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; Pip, pipecolic acid.

Experimental section: syntheses and analytical data of compounds, enzyme assays, docking procedures. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.012.

Supplementary data

References and notes

- 1.Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Snijder E.J. Coronaviruses, Toroviruses, and Arteriviruses. In: Mahy B.W.J., ter Meulen V., editors. 10th Ed. Vol. 1. Hodder Arnold; London: 2005. pp. 823–856. (Topley’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C., Günther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., Berger A., Burguiere A.M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N., Grywna K., Kramme S., Manuguerra J.C., Muller S., Rickerts V., Sturmer M., Vieth S., Klenk H.D., Osterhaus A.D., Schmitz H., Doerr H.W. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., Rollin P.E., Dowell S.F., Ling A.E., Humphrey C.D., Shieh W.J., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., Rota P., Fields B., DeRisi J., Yang J.Y., Cox N., Hughes J.M., LeDuc J.W., Bellini W.J., Anderson L.J. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Lancet. 2003;361:1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziebuhr J. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:412. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziebuhr J. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;287:57. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziebuhr J., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;8:853. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. EMBO J. 2002;21:3213. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Science. 2003;300:1763. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., Gao G.F., Anand K., Bartlam M., Hilgenfeld R., Rao Z. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:13190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B., Zhou J. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:484. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajnarayanan R.V., Dakshanamurthy S., Pattabiranam N. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou K.-C., Wei D.-Q., Zhong W.-Z. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;308:148. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenwitheesuk E., Samudrala R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:3989. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X.W., Yap Y.L., Altmeyer R.M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005;40:57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Q., Wang S., Wei D., Sirois S., Chou K.-C. Anal. Biochem. 2005;337:262. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong B., Gui C.-S., Xu X.-Y., Luo C., Chen J., Luo H.-B., Chen L.-L., Li G.-W., Sun T., Yu C.-Y., Yue L.-D., Duan W.-H., Shen J.-K., Qin L., Li Y.-X., Chen K.-X., Luo X.-M., Shen X., Shen J.-H., Jiang H.-L. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2003;24:497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X.-W., Yap Y.L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:2517. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toney J.H., Navas-Martin S., Weiss S.R., Koeller A. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1079. doi: 10.1021/jm034137m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C.Y., Jan J.T., Ma S.H., Kuo C.J., Juan H.F., Cheng Y.S., Hsu H.H., Huang H.C., Wu D., Brik A., Liang F.S., Liu R.S., Fang J.M., Chen S.T., Liang P.H., Wong C.H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchard J.E., Elowe N.H., Huitema C., Fortin P.D., Cechetto J.D., Eltis L.D., Brown E.D. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1445. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kao R.Y., To A.P.C., Ng L.W.Y., Tsui W.H.W., Lee T.S.W., Tsoi H.-W., Yuen K.-Y. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:325. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu J.T.-A., Kuo C.-J., Hsieh H.-P., Wang Y.-C., Huang K.-K., Lin C.P.-C., Huang P.-F., Chen X., Liang P.-H. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:116. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacha U., Barrila J., Velazquez-Campoy A., Leavitt S.A., Freire E. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4906. doi: 10.1021/bi0361766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Käppler, U.; Stiefl, N.; Schiller, M.; Vicik, R.; Breuning, A.; Schmitz , W.; Rupprecht, D.; Schmuck, C.; Baumann, K.; Ziebuhr, J.; Schirmeister, T.; J. Med. Chem.2005 accepted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Schirmeister T., Klockow A. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2003;3:585. doi: 10.2174/1389557033487935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vicik, R.; Busemann, M.; Gelhaus, C.; Stiefl, N.; Scheiber, J.; Schmitz, W.; Schulz, F.; Mladenovic, M.; Engels, B.; Leippe, M.; Baumann, K.; Schirmeister, T.; J. Med. Chem.2005 in revision. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Powers J.C., Asgian J.L., Ekici Ö.D., James K.E. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4639. doi: 10.1021/cr010182v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ro S., Baek S.G., Lee B., Ok J.H. J. Pept. Res. 1999;54:242. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanada K., Tamai M., Morimoto S., Adachi T., Ohmura S., Sawada J., Tanaka I. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1978;42:537. [Google Scholar]

- 31.For classification of proteases see: http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/index.htm.

- 32.Kleina L.G., Grubman M.J. J. Virol. 1992;66:7168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7168-7175.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seybert A., Ziebuhr J., Siddell S.G. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:71. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziebuhr J., Heusipp G., Siddell S.G. J. Virol. 1997;71:3992. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3992-3997.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegyi A., Ziebuhr J. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:595. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirmeister T., Breuning A., Murso A., Stalke D., Mladenovic M., Engels B., Szeghalmi A., Schmitt M., Kiefer W., Popp J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2004;108:11398. [Google Scholar]

- 37.2c is an irreversible inhibitor (kobs/I = 311 ± 60 M−1 min−1) which means that inhibition is time-dependent. Hence the higher value for inhibition by 2c obtained in the HPLC assay compared to the fluorimetric assay is due to the much longer incubation time of the former.

- 38.Schirmeister T. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 1996;329:239. [Google Scholar]

- 39.FlexX® 112 BioSolveIT, An der Ziegelei 75, 53757 St. Augustin, Germany 2003.

- 40.Chou C.Y., Chang H.C., Hsu W.C., Lin T.Z., Lin C.H., Chang G.G. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14958. doi: 10.1021/bi0490237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.