Abstract

A series of thiazole clubbed 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives (5a–l) have been synthesized and characterized by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and mass spectral analysis. Synthesized compounds were evaluated for their antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. The results indicated that, compounds 5c and 5i exhibited the most potent antibacterial activity. Compound 5f was found to be the most potent antifungal agent. The structure activity relationship revealed that the presence of electron withdrawing groups at para position of phenyl ring remarkably enhanced the antibacterial activity of synthesized compounds. Further, the results of preliminary MTT cytotoxicity studies on HeLa cells suggested that potent antimicrobial activity of 5b, 5c, 5f, 5h and 5i is accompanied by low cytotoxicity.

Keywords: Thiazole; 1,3,4-Oxadiazole; Thiazole clubbed 1,3,4-oxadiazoles; Antibacterial activity; Antifungal activity; Cytotoxicity

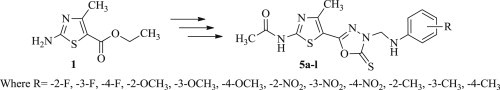

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A series of novel thiazole clubbed 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives were synthesized.

-

•

The newly synthesized compounds were evaluated for their in vitro antimicrobial activity.

-

•

Some of the compounds exhibited potent antibacterial activity (2- to 4-fold higher) compared to the standard drugs.

-

•

The structure activity relationships revealed importance of substitution pattern on biological activity.

-

•

It was established that structural requirements are different for binding of drug to bacterial or fungal targets.

1. Introduction

The treatment of infectious diseases still remain a challenging task because of combination of factors such as an alarming increase in number of multi-drug-resistant microbial pathogens and advent of newer infectious diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and avian influenza. Despite the availability of a large number of antibiotics and chemotherapeutics, the increasing clinical importance of drug-resistant microbial pathogens have lent additional urgency in microbiological and antifungal research [1], [2], [3], [4]. A potential solution to the antibiotic resistance is to design and explore innovative heterocyclic agents with novel mode of actions. In this context, thiazole derivatives have been playing a crucial role in medicinal chemistry. Thiazole nucleus constitutes an integral part of all the available penicillins, which have transformed the bacterial diseases therapy [5]. They display quite a broad spectrum of biological activities [6], which have found applications in the treatment of allergies [7], hypertension [8], inflammation [9], schizophrenia [10], microbial infections [11], [12], HIV infections [13], hypnotics [14] and pain [15]. They are also used as new inhibitors of bacterial DNA gyrase B [16]. Further, thiazoles have emerged as new class of potent antimicrobial agents, which are reported to inhibit bacteria by blocking the biosynthesis of certain bacterial lipids and/or by additional mechanisms [17], [18].

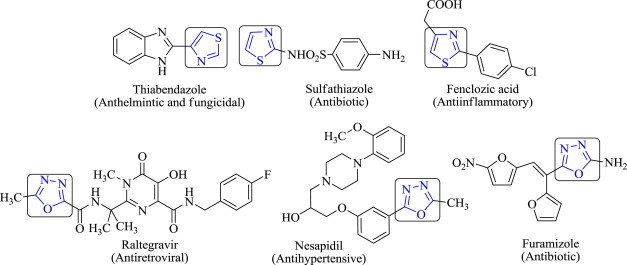

On the other hand, 1,3,4-oxadiazole heterocycles are very good bioisosteres of amides and esters, which can contribute substantially in enhancing pharmacological activity by participating in hydrogen bonding interactions with the receptors [19]. Potent pharmacological activity of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles can be attributed to the presence of toxophoric –N C–O– linkage which may react with the nucleophilic centers of the microbial cell [20]. Further, the widespread use of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles as a scaffold in medicinal chemistry established this moiety as a member of the privileged structures class and its derivatives have exhibited a wide range of biological activities such as antibacterial [21], antitubercular [22], vasodialatory [23], antifungal [24], cytotoxic [25], anti-inflammatory and analgesic [26], [27], hypolipidemic [28], anticancer [29] and ulcerogenic [30]. Oxadiazole derivatives have been found to possess broad spectrum antimicrobial activity and therefore are useful substructures for further molecular exploration [30]. The most prominent examples of prescribed agents featuring the 1,3,4-oxadiazoles nucleus include the antiretroviral raltegravir [31], antihypertensive nesapidil [32] and the antibiotic furamizole [33] (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Commercially available drugs containing thiazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole nucleus.

Prompted by above-mentioned observations and in continuation of our search for new, potent, selective, and less toxic antimicrobial agents [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], we report herein the synthesis of some novel structural hybrids by combining thiazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole pharmacophores in single molecular framework in order to investigate their in vitro antimicrobial activity. In addition, cytotoxicity studies were also conducted in HeLa cell lines to evaluate the ability of these compounds to inhibit the cell growth. The substitution pattern of 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring was carefully selected in order to confer different electronic environment to the molecules.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

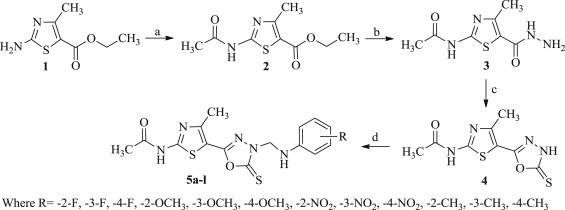

The reaction sequences employed for synthesis of the target compounds 5a–l are outlined in Scheme 1 . Ethyl 2-amino-4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylate (1) was taken as starting material and reacted with acetic anhydride to afford ethyl 2-acetamido-4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylate (2), which on further reaction with hydrazine hydrate in absolute ethanol yielded intermediate N-(5-(hydrazine carbonyl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (3). The intermediate obtained thus, was refluxed with carbon disulfide in the presence of potassium hydroxide in ethanol (99.5%) to yield intermediate N-(4-methyl-5-(5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (4). Mannich condensation of intermediate 4 with 36% formaldehyde and an appropriately substituted aniline derivative in ethanol (99.5%) furnished the desired compounds 5a–l. Both analytical and spectral data of the synthesized compounds 5a–l were fully in agreement with proposed structures.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes for the compounds 5a–l. Reagents and conditions: (a) (CH3CO)2O, reflux, 1 h; (b) NH2NH2.H2O, EtOH, reflux, 5 h; (c) CS2, KOH, EtOH, reflux, 12 h; (d) R-C6H4NH2, HCHO, reflux, 3h.

Formation of titled compounds 5a–l was confirmed by characteristic IR spectrum absorption bands in the range of 3330–3350 cm−1, 3200–3250 cm−1, 2810–2840 cm−1, 2750–2800 cm−1 and 1660–1690 cm−1 corresponding to –NH stretching of secondary amine, –NH stretching of amide, –CH3, –CH2– and >C O of amide respectively. Singlets at around δ 2.03–2.10, 2.40–2.50, 4.15–4.25, 4.35–4.45 and 9.10–9.20 ppm in 1H NMR were due to –CH3 in anilide group, Het–CH3, secondary amine, –CH2– and –NH amide group respectively. The aromatic ring protons were observed at δ 6.20–8.05 ppm and J value were found to be in accordance with substitution pattern on phenyl ring. Characteristic peaks at around δ 168.5–168.9 and 177.0–177.3 ppm in 13C NMR confirmed the presence of >C O and >C S groups respectively. The mass spectrum of 5a–l revealed that observed molecular ion peaks were in agreement with molecular weight of respective compound.

2.2. Antimicrobial studies

2.2.1. Antibacterial studies

All the synthesized compounds 5a–l were evaluated for their in vitro antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96, Streptococcus pyogenes MTCC 442 (Gram-positive), Escherichia coli MTCC 443 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1688 (Gram-negative) by conventional broth microdilution method using chloramphenicol as a control drug for antibacterial activity [40]. The results of the antimicrobial studies are presented in Table 1 . In general, compounds 5a–l demonstrated better antibacterial activity than antifungal activity. Compounds 5c and 5i emerged as the most effective antibacterial agents with 2- to 4-fold higher MIC (12.5–25 μg/mL) than the reference drug chloramphenicol. While, compounds 5b and 5h exhibited comparable antibacterial activity with the standard drug. From the results of the antimicrobial activity of the synthesized compounds 5a–l, the following structure activity relationships can be derived: the antibacterial activity was considerably affected by substitution pattern on the phenyl ring and the most active compounds contain electron withdrawing substituent at para and meta positions of the phenyl ring (p > m > o). In contrast, the presence of electron releasing groups on the phenyl ring witnessed a substantial decrease in antibacterial activity for compounds 5d–f and 5k–l. The role of electron withdrawing group in improving antimicrobial activity is very well supported by previous studies [41], [42]. Compounds 5c and 5i, substituted with inductively electron withdrawing fluoro and nitro groups, respectively at para position showed the highest antibacterial activity (F > NO2). It is a very well-known fact that electron withdrawing substitution such as fluoro/nitro at the para position of the aromatic ring increases the lipophilicity of molecules. This property is directly related to antimicrobial activity as it facilitates a compound to diffuse through the biological membranes and reach to its site of action. The presence of lipophilic substituent at para position of phenyl ring provided a positive influence on antibacterial activity. On the other hand, presence of the same functional groups at meta position resulted in slight decrease in the antibacterial activity (5b and 5h) but, still produced significant inhibitory action compared to the standard drug chloramphenicol (F > NO2). While, substituting the phenyl ring with fluoro and nitro group at ortho position resulted in noticeable decrease in the antibacterial activity of compounds 5a and 5g respectively. On the basis of MIC values, it may be concluded that electron withdrawing atom/group such as fluoro and nitro at the para position of phenyl ring induced a positive effect while electron donating groups such as methyl and methoxy induced a negative effect on antibacterial activity of compounds 5a–l.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial screening results of compounds 5a–l.

| Entry | R | Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), μg/mL |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteriaa |

Gram-negative bacteriab |

Fungic |

||||||

| Sa | Sp | Ec | Pa | Ca | An | Ac | ||

| 5a | –2-F | 250 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 500 | >1000 | 500 |

| 5b | –3-F | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 500 | 500 | >1000 |

| 5c | –4-F | 12.5 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 500 | 500 | >1000 |

| 5d | –2-OCH3 | 500 | >1000 | 500 | 250 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| 5e | –3-OCH3 | >1000 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 100 | 500 |

| 5f | –4-OCH3 | 500 | >1000 | 500 | 500 | 25 | 25 | 62.5 |

| 5g | –2-NO2 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 |

| 5h | –3-NO2 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 500 | 100 | 250 |

| 5i | –4-NO2 | 25 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 500 | 250 | 100 |

| 5k | –2-CH3 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 100 | 500 | 500 | 250 |

| 5k | –3-CH3 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 5l | –4-CH3 | 500 | >1000 | 500 | >1000 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| Chloramphenicol | – | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | – | – | – |

| Ketoconazole | – | – | – | – | – | 50 | 50 | 50 |

Sa (Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96); Sp (Staphylococcus pyogenes MTCC 442).

Ec (Escherichia coli MTCC 443); Pa (Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1688).

Ca (Candida albicans MTCC 227); An (Aspergillus niger MTCC 282); Ac (Aspergillus clavatus MTCC 1323).

2.2.2. Antifungal studies

The in vitro antifungal activity of synthesized compounds 5a–l were determined against Candida albicans MTCC 227, Aspergillus niger MTCC 282 and Aspergillus clavatus MTCC 1323 by conventional broth microdilution method. The results indicated that compound 5f substituted with methoxy group at para position of the phenyl ring was found to be the most promising agent against both C. albicans and A. niger having 2-fold higher MIC (25 μg/mL) in comparison with control drug ketoconazole. The enhanced activity of compound 5f may be attributed to the presence of electron releasing group at para position. The contrasting nature of substitution pattern at para position of the phenyl ring of most active antibacterial and antifungal agents indicate that the structural requirements are different for binding of drug to bacterial or fungal targets, respectively [43]. All other compounds showed less inhibition against the tested microorganisms as compared to the standard drug.

2.2.3. Cytotoxicity studies

In vitro cytotoxicity of compounds 5b, 5c, 5f, 5h and 5i were evaluated against human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa) by the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay [44], which measures the reduction of tetrazolium bromide salt into a formazan dye by mitochondrial dehydrogenases in treated versus untreated cells. The results are summarized in Table 2 . It was observed that none of the tested compounds exhibited any significant cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, suggesting a great potential for their in vivo use as antimicrobial agents.

Table 2.

Levels of cytotoxicity induced by selected compounds on HeLa cells at 24 h of drug exposure.

| Compounds | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| 5b | >100 |

| 5c | >100 |

| 5f | 98.60 |

| 5h | >100 |

| 5i | 96.48 |

| Doxorubicin | 3.24 |

The known numbers of cells (1.0 × 104) were incubated for 24 h in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C in the presence of different concentrations of test compounds. After 24 h of drug incubation the MTT solution was added and supernatant was discarded and 100 mL DMSO was added in each well and absorbance was recorded at 540 nm by ELISA reader.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, some new structural hybrids of thiazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole were synthesized and investigated for their antimicrobial property with an anticipation of generating new structural leads serving as potent antimicrobial agents. Many of the synthesized motifs (5b, 5c, 5h and 5i), possessing electron withdrawing atom/group such as fluoro and nitro at para and meta positions were identified as the most potent antibacterial agents. Albeit, it was observed that para position was more favorable for enhancing the antibacterial activity. While, compound 5f with electron releasing group at para position came out as the most promising antifungal agent. The potent antimicrobial activity of most active compounds 5b, 5c, 5f, 5h and 5i were accompanied with relatively low level of cytotoxicity. The results described here, merits further investigations in our laboratories using a forward chemical genetic approach for finding lead molecules as antimicrobial agents.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

All reactions except those in aqueous media were carried out by standard techniques for the exclusion of moisture. Melting points were determined on an electrothermal melting point apparatus and were reported uncorrected. TLC on silica gel plates (Merck, 60, F254) was used for purity checking and reaction monitoring. Column chromatography on silica gel (Merck, 70–230 mesh and 230–400 mesh ASTH for flash chromatography) was applied when necessary to isolate and purify the reaction products. Elemental analysis (% C, H, N) was carried out by a Perkin–Elmer 2400 CHN analyzer. IR spectra of all compounds were recorded on a Perkin–Elmer FT-IR spectrophotometer in KBr. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Gemini 300 MHz and 13C NMR spectra on Varian Mercury-400 100 MHz in DMSO-d 6 as a solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Mass spectra were scanned on a Shimadzu LC-MS 2010 spectrometer. All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were carried out under nitrogen atmosphere using oven-dried glassware.

4.2. Synthesis of intermediate ethyl 2-acetamido-4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylate (2)

Ethyl 2-amino-4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylate (0.01 mol) was taken in a round bottom flask and acetic anhydride (0.02 mol) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed at 140–150 °C for 1 h and then poured into cold water under constant stirring to get solid product. The mixture was heated to boiling to decompose excess of acetic anhydride and cooled. The solid obtained was filtered, washed with water and dried. The ethyl 2-(acetyl amino)-4-methyl-1,3-thiazole-5-carboxylate was collected and recrystallized from ethanol to get pure white crystals. Yield: 74%; m.p. 158 °C; Anal. obs. C, 47.08%; H, 5.48%; N, 12.44%. Calcd. for C9H12N2O3S: C, 47.35%; H, 5.30%; N, 12.27%.

4.3. Synthesis of intermediate N-(5-(hydrazinecarbonyl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (3)

Intermediate (2) (0.01 mol) and 99% hydrazine hydrate (0.015 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask and mixture was refluxed for 10 min. Alcohol was added till both the layers were miscible and refluxing was continued for 5 h. Excess of alcohol and unreacted hydrazine hydrate was distilled out and the contents were poured into a beaker. The solid was recrystallized from ethanol to get pure crystalline product. Yield: 64%; m.p. 172 °C; Anal. obs. C, 38.98%; H, 4.82%; N, 26.37%. Calcd. for C7H10N4O2S: C, 39.24%; H, 4.70%; N, 26.15%.

4.4. Synthesis of intermediate N-(4-methyl-5-(5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (4)

A mixture of intermediate (3) (0.01 mol), potassium hydroxide (0.01 mol), carbon disulfide (0.02 mol) and ethanol (99.5%) (100 mL) was refluxed for 12 h. The excess solvent was removed by vacuum evaporation, and the residue was dissolved in water and acidified with acetic acid to get solid product. It was filtered, dried and recrystallized from water–ethanol (60–40). Yield: 64%; m.p. 198 °C; Anal. obs. C, 37.65%; H, 3.32%; N, 22.06%. Calcd. for C8H8N4O2S2: C, 37.49%; H, 3.15%; N, 21.86%.

4.5. General procedure for the synthesis of N-(5-(4-(((aryl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5a–l)

A mixture of intermediate (4) (0.01 mol) and an appropriately substituted aniline derivatives (0.01 mol) was refluxed in ethanol (50 mL) with 36% formaldehyde (0.02 mol) for 3 h. The resulting solid was crystallized from a suitable solvent.

4.5.1. N-(5-(4-(((2-fluorophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5a)

Yield: 64%, m.p. 178–180 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3331 (secondary amine NH), 3211 (secondary amide NH), 3028 (aromatic ring CH), 2831 (CH3), 2762 (CH2), 1681 (CO), 1113 (CF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.05 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.44 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.11 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.44 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.56–7.10 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.17 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.0 (CH3), 24.1 (COCH3), 70.6 (CH2), 115.2, 116.3, 121.3, 125.1, 130.6, 132.4, 154.3 (C–F), 156.6 (C–CH3), 157.1, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 379.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C15H14FN5O2S2 C-47.48, H-3.72, N-18.46; Found: C-47.34, H-3.68, N-18.57%.

4.5.2. N-(5-(4-(((3-fluorophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5b)

Yield: 61%, m.p. 166–168 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3330 (secondary amine NH), 3217 (secondary amide NH), 3023 (aromatic ring CH), 2830 (CH3), 2769 (CH2), 1669 (CO), 1111 (CF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.04 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.46 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.10 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.54–7.22 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.15 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.2 (CH3), 24.1 (COCH3), 70.7 (CH2), 102.2, 108.9, 109.3, 131.1, 132.6, 149.2, 156.6 (C–CH3), 157.1, 162.9, 163.7 (C–F), 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 379.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C15H14FN5O2S2 C-47.48, H-3.72, N-18.46; Found: C-47.31, H-3.73, N-18.51%.

4.5.3. N-(5-(4-(((4-fluorophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5c)

Yield: 59%, m.p. 132–134 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3329 (secondary amine NH), 3210 (secondary amide NH), 3022 (aromatic ring CH), 2839 (CH3), 2760 (CH2), 1678 (CO), 1117 (CF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.04 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.41 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.13 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.44 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 7.02–7.05 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.16 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (CH3), 24.1 (COCH3), 70.6 (CH2), 116.3 (2C), 118.9 (2C), 132.5, 143.4, 155.7 (C–F), 156.5 (C–CH3), 157.1, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.2 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 379.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C15H14FN5O2S2 C-47.48, H-3.72, N-18.46; Found: C-47.31, H-3.64, N-18.54%.

4.5.4. N-(5-(4-(((2-methoxyphenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5d)

Yield: 58%, m.p. 139–141 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3331 (secondary amine NH), 3208 (secondary amide NH), 3020 (aromatic ring CH), 2831 (CH3), 2766 (CH2), 1672 (CO), 1211–1103 (C–O–C). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.04 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.44 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.13 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 3.71 (s, 3H, Ar–OCH 3), 4.44 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.66–7.02 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.16 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (CH3), 24.0 (COCH3),55.7 (OCH3), 71.2 (CH2), 113.5, 114.4, 121.1, 121.7, 132.4, 138.4, 144.5 (C–OCH3), 156.4 (C–CH3), 162.9, 168.7 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 391.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-49.09, H-4.38, N-17.89; Found: C-49.23, H-4.25, N-18.30%.

4.5.5. N-(5-(4-(((3-methoxyphenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl) acetamide (5e)

Yield: 58%, m.p. 139–141 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3344 (secondary amine NH), 3223 (secondary amide NH), 3020 (aromatic ring CH), 2833 (CH3), 2784 (CH2), 1674 (CO), 1204–1093 (C–O–C). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.07 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.44 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 3.75 (s, 3H, Ar–OCH 3), 4.15 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.44 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.20–7.30 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.20 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1(CH3), 24.0 (COCH3), 55.7 (OCH3), 70.9 (CH2), 105.5, 105.8, 109.2, 110.3, 132.4, 148.5, 156.4 (C–CH3), 157.0, 161.4 (C–OCH3), 162.9, 168.7 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 391.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-49.09, H-4.38, N-17.89; Found: C-49.25, H-4.49, N-17.78%.

4.5.6. N-(5-(4-(((4-methoxyphenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5f)

Yield: 59%, m.p. 150–152 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3339 (secondary amine NH), 3228 (secondary amide NH), 3011 (aromatic ring CH), 2832 (CH3), 2780 (CH2), 1670 (CO), 1211–1099 (C–O–C). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.04 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.45 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 3.83 (s, 3H, Ar–OCH 3), 4.21 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.77–7.18 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.15 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1(CH3), 24.0(COCH3), 55.8 (OCH3), 70.8 (CH2), 115.1 (2C), 115.8 (2C), 132.4, 139.9, 151.7 (C–OCH3), 156.4 (C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.7 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 391.1 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-49.09, H-4.38, N-17.89; Found: C-49.17, H-4.52, N-17.98%.

4.5.7. N-(4-methyl-5-(4-(((2-nitrophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5g)

Yield: 52%, m.p. 155–157 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3327 (secondary amine NH), 3224 (secondary amide NH), 3014 (aromatic ring CH), 2833 (CH3), 2784 (CH2), 1671 (CO), 1533 (NO2). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.03 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.46 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.24 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 7.34–8.05 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.14 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.0 (CH3), 24.0 (COCH3), 69.7 (CH2), 114.3, 118.1, 126.1, 131.8, 132.4, 135.7, 146.7, 156.4 (C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.7 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 406.05 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-44.33, H-3.47, N-20.68; Found: C-44.44, H-3.32, N-20.78%.

4.5.8. N-(4-methyl-5-(4-(((3-nitrophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5h)

Yield: 55%, m.p. 165–167 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3329 (secondary amine NH), 3225 (secondary amide NH), 3010 (aromatic ring CH), 2838 (CH3), 2781 (CH2), 1672 (CO), 1538 (NO2). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.03 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.44 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.18 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.43 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 7.20–7.60 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.14 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (CH3), 24.0 (COCH3), 70.7 (CH2), 106.8, 112.1, 119.5, 130.5, 132.4, 148.5, 148.7, 156.4 (C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.7 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 406.01 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-44.44, H-3.47, N-20.68; Found: C-44.20, H-3.39, N-20.62%.

4.5.9. N-(4-methyl-5-(4-(((4-nitrophenyl)amino)methyl)-5-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5i)

Yield: 60%, m.p. 159–161 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3331 (secondary amine NH), 3227 (secondary amide NH), 3010 (aromatic ring CH), 2830 (CH3), 2782 (CH2), 1671 (CO), 1524 (NO2). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.03 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.45 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.11 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.41 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.72–8.04 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.15 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (CH3), 24.0 (COCH3), 70.9 (CH2), 114.4 (2C), 127.5 (2C), 132.4, 136.4, 153.7, 156.4 (C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 406.01 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O3S2 C-44.44, H-3.47, N-20.68; Found: C-44.56, H-3.60, N-20.75%.

4.5.10. N-(4-methyl-5-(5-thioxo-4-((o-tolylamino)methyl)-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5j)

Yield: 62%, m.p. 142–144 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3331 (secondary amine NH), 3220 (secondary amide NH), 3022 (aromatic ring CH), 2953 (Ar–CH3), 2840 (Het–CH3), 2771 (CH2), 1681 (CO). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.04 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.12 (Ar–CH3), 2.46 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.09 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.63–7.04 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.16 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (Het–CH3), 17.6 (Ar–CH3), 24.1 (COCH3), 71.2 (CH2), 110.6, 121.8 (Ar–C–CH3), 122.1, 126.5, 127.0, 132.3, 146.5, 156.5 (Het–C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 375.08 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O2S2 C-51.18, H-4.56, N-18.65; Found: C-51.30, H-4.40, N-18.52%.

4.5.11. N-(4-methyl-5-(5-thioxo-4-((m-tolylamino)methyl)-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5k)

Yield: 57%, m.p. 151–153 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3330 (secondary amine NH), 3229 (secondary amide NH), 3027 (aromatic ring CH), 2951 (Ar–CH3), 2830 (Het–CH3), 2775 (CH2), 1680 (CO). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.03 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.34 (Ar–CH3), 2.42 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.07 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.52–7.11 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.16 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (Het–CH3), 21.2 (Ar–CH3), 24.1 (COCH3), 70.8 (CH2), 110.5, 113.2117.4, 129.4, 132.4, 132.3, 139.3 (Ar–C–CH3), 147.5, 156.5 (Het–C–CH3), 157.0, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 375.08 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O2S2 C-51.18, H-4.56, N-18.65; Found: C-51.00, H-4.48, N-18.76%.

4.5.12. N-(4-methyl-5-(5-thioxo-4-((p-tolylamino)methyl)-4,5-dihydro-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)thiazol-2-yl)acetamide (5l)

Yield: 61%, m.p. 163–165 °C; IR (KBr): v/cm−1 3327 (secondary amine NH), 3228 (secondary amide NH), 3029 (aromatic ring CH), 2947 (Ar–CH3), 2839 (Het–CH3), 2775 (CH2), 1687 (CO). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 2.07 (s, 3H, –NHCOCH 3), 2.34 (Ar–CH3), 2.43 (s, 3H, –N–C(CH 3)–C–), 4.10 (s, 1H, Ar–NH–CH2), 4.41 (s, 2H, Het–CH 2–NH), 6.48–7.01 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 9.16 (s, 1H, Het–NH–CO); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ ppm: 17.1 (Het–CH3), 21.3 (Ar–CH3), 24.0 (COCH3), 70.8 (CH2), 113.4 (2C), 129.6 (Ar–C–CH3), 129.8 (2C), 132.3, 144.6, 156.5 (Het–C–CH3), 157.1, 162.9, 168.9 (amide C O) and 177.1 (C S); MS (EI): m/z 375.08 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C16H17N5O2S2 C-51.18, H-4.56, N-18.65; Found: C-51.42, H-4.44, N-18.72%.

4.6. Biological assay

4.6.1. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity

All MTCC cultures were collected from Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh. The MICs of synthesized compounds were carried out by broth microdilution method against the standard bacterial strains S. aureus MTCC 96, S. pyogenes MTCC 442, E. coli MTCC 443 and P. aeruginosa MTCC 1688 and antifungal activity against the standard fungal strains C. albicans MTCC 227, A. niger MTCC 282 and A. clavatus MTCC 1323. DMSO was used as diluents to get desired concentration of compounds to test upon standard bacterial strains. Serial dilutions were prepared in primary and secondary screening. The control tube containing no antibiotic was immediately subcultured (before inoculation) by spreading a loopful evenly over a quarter of plate of medium suitable for the growth of the test organism and put for incubation at 37 °C overnight. The tubes were then incubated overnight. The MIC of the control organism was read to check the accuracy of the compound concentrations. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antibiotic or test sample allowing no visible growth. All the tubes showing no visible growth (same as control tube) were subcultured and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The amount of growth from the control tube before incubation (which represents the original inoculum) was compared. Subcultures might show: similar number of colonies indicating bacteriostatic; a reduced number of colonies indicating a partial or slow bactericidal activity and no growth if the whole inoculum has been killed. The test must include a second set of the same dilutions inoculated with an organism of known sensitivity. Each synthesized compound was diluted obtaining 2000 μg/mL concentration as a stock solution. In primary screening 500, 250 and 200 μg/mL concentrations of the synthesized compounds were taken. The active synthesized compounds found in this primary screening were further tested in a second set of dilution against all microorganisms. The compounds found active in primary screening were similarly diluted to obtain 100, 62.5, 50 and 25 μg/mL concentrations. The highest dilution showing at least 99% inhibition is taken as MIC.

4.6.2. Preliminary in vitro cytotoxic activities (MTT assay)

In vitro cytotoxicity was determined using a standard MTT assay with protocol appropriate for the individual test system. Test compounds were prepared prior to the experiment by dissolving in 0.1% DMSO and diluted with medium. The cells were then exposed to different concentrations of the drugs (1–100 μM) in the volume of 100 μM/well. Cells in the control wells received the same volume of medium containing 0.1% DMSO. After 24 h, the medium was removed and cell cultures were incubated with 100 μl MTT reagent (1 mg/mL) for 5 h at 37 °C. The suspension was placed on micro vibrator for 10 min and absorbance was recorded by the ELISA reader. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Human cancer cell lines, HeLa cells were cultured in MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine and 50 μM/mL gentamicin sulphate in a CO2 incubator in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Chemistry, Mahatma Gandhi Campus, Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University, Bhavnagar for providing research and library facilities.

References

- 1.Grare M., Mourer M., Fontanay S., Regnouf-de-Vains J.B., Finance C., Duval R.E. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:575–581. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeltz R.F., Wilkinson B.J. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004;4:273–294. doi: 10.2174/1568005043340470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenover F.C., McDonald L.C. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2005;18:300–305. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000171923.62699.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts M.C. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004;4:207–215. doi: 10.2174/1568005043340678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oncu S., Punar M., Erakosy H. Chemotherapy. 2004;50:98–100. doi: 10.1159/000077810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashyap S.J., Garg V.K., Sharma P.K., Kumar N., Dudhe R., Gupta J.K. Med. Chem. Res. 2012;21:2123–2132. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargrave K.D., Hess F.K., Oliver J.T. J. Med. Chem. 1983;26:1158–1163. doi: 10.1021/jm00362a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patt W.C., Hamilton H.W., Taylor M.D., Ryan M.J., Taylor D.G., Jr., Connolly C.J.C., Doherty A.M., Klutchko S.R., Sircar I., Steinbaugh B.A., Batley B.L., Painchaud C.A., Rapundalo S.T., Michniewicz B.M., Olso S.C.J. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:2562–2572. doi: 10.1021/jm00092a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma R.N., Xavier F.P., Vasu K.K., Chaturvedi S.C., Pancholi S.S. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009;24:890–897. doi: 10.1080/14756360802519558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaen J.C., Wise L.D., Caprathe B.W., Tecle H., Bergmeier S., Humblet C.C., Heffner T.G., Meltzner L.T., Pugsley T.A. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:311–317. doi: 10.1021/jm00163a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omar K., Geronikoki A., Zoumpoulakis P., Camoutsis C., Sokovic M., Ciric A., Glamoclija J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaras K., Geronikoki A., Glamoclija J., Ciric A., Sokovic M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:3135–3140. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell F.W., Cantrell A.S., Hogberg M., Jaskunas S.R., Johansson N.G., Jordon C.L., Kinnick M.D., Lind P., Morin J.M., Jr., Noreen R., Oberg B., Palkowitz J.A., Parrish C.A., Pranc P., Sahlberg C., Ternansky R.J., Vasileff R.T., Vrang L., West S.J., Zhang H., Zhou X.X. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:4929–4936. doi: 10.1021/jm00025a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ergenc N., Capan G., Gunay N.S., Ozkirimli S., Gungor M., Ozbey S., Kendi E. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 1999;332:343–347. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(199910)332:10<343::aid-ardp343>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter J.S., Kramer S., Talley J.J., Penning T., Collins P., Graneto M.J., Seibert K., Koboldt C., Masferrer J., Zweifel B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:1171–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudolph J., Theis H., Hanke R., Endermann R., Johannsen L., Geschke F.U. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:619–626. doi: 10.1021/jm0010623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalaf Abedawn I., Waigh Roger D. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2133–2156. doi: 10.1021/jm031089x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harnet J.J., Roubert V., Dolo C., Charnet C., Spinnewyn B., Cornet S., Rolland A., Marin J.G., Bigg D., Chabrier P.E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guimaraes C.R.W., Boger D.L., Jorgensen W.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17377–17384. doi: 10.1021/ja055438j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigo B., Couturier D. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1985;22:287–288. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbucenu S.F., Bancescu G., Cretu O.D., Draghici C., Bancescu A., Radu-Popescu M. Rev. Chem. (Bucuresti) 2010;61:140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suresh Kumar G.V., Rajendraprasad Y., Mallikarjuna B.P., Chandrashekar S.M., Kistayya C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:2063–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirote P.J., Bhatia M.S. Arab. J. Chem. 2011;4:413–418. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakash O., Kumar M., Kumar R., Sharma C., Aneja K.R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:4252–4257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padmavathi V., Sudhakar Reddy G., Padmaja A., Kondaiah P., Ali S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:2106–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akhter M., Husain A., Azad B., Ajmal M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:2372–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idrees G.A., Aly O.M., Abuo-Rahma Gel D., Radwan M.F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:3973–3980. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayashankar B., Lokanath Rai K.M., Baskaran N., Sathish H.S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:3898–3902. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar D., Sundaree S., Johnson E.O., Shah K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:4492–4494. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhandari S.V., Bothara K.G., Raut M.K., Patil A.A., Sarkate A.P., Mokale V.J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;16:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laufer R., Paz O.G., Di Marco A., Bonelli F., Monteagudo E., Summa V., Rowley M. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009;37:873–883. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlecker R., Thieme P.C. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:3289–3294. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogata M., Atobe H., Kushida H., Yamamoto K. J. Antibiot. 1971;24:443–451. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.24.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai N.C., Rajpara K.M., Joshi V.V., Vaghani H.V., Satodiya H.M. Med. Chem. Res. 2013;22:1172–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai N.C., Joshi V.V., Rajpara K.M. Med. Chem. Res. 2012:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desai N.C., Rajpara K.M., Joshi V.V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013;145:102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desai N.C., Rajpara K.M., Joshi V.V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:6871–6875. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desai N.C., Joshi V.V., Rajpara K.M., Vaghani H.V., Satodiya H.M. Med. Chem. Res. 2013;22:1893–1908. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desai N.C., Joshi V.V., Rajpara K.M., Vaghani H.V., Satodiya H.M. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012;142:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hannan P.C. Vet. Res. 2000;31:373–395. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma P., Rane N., Gurram V.K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:4185–4190. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma D., Narasimhan B., Kumar P., Judge V., Narang R., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:2347–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sortino M., Delgado P., Juarez S., Quiroga J., Abonia R., Insuasty B., Nogueras M., Rodero L., Garibotto F.M., Enriz R.D., Zacchino S.A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;15:484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosmann T. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]