Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a highly contagious and sometimes a lethal disease, which spread over five continents in 2002–2003. Laboratory analysis showed that the etiologic agent for SARS is a new type of coronavirus. Currently, there is no specific treatment for this disease. RNA interference (RNAi) is a recently discovered antiviral mechanism in plant and animal cells that induces a specific degradation of double-stranded RNA. Here, we provide evidences that RNAi targeting at coronavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP) using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression plasmids can specifically inhibit expression of extraneous coronavirus RDRP in 293 and HeLa cells. Moreover, this construct significantly reduced the plaque formation of SARS coronaviruses in Vero-E6 cells. The data may suggest a new approach for treatment of SARS patients.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Coronavirus, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP), RNA interference (RNAi), Short hairpin RNA (shRNA), Short interfering RNA (siRNA)

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a highly contagious disease. An outbreak in 2002–2003 affected more than 8000 patients in over 30 countries across five continents. In some areas, the mortality reached as high as 10% of the infected patients (WHO). Viruses isolated from SARS patients have been confirmed to be a new type of coronavirus that is responsible for the outbreak Enserink and Normile, 2003, Guan et al., 2003, Lai, 2003, Yan et al., 2003. Coronaviruses are large enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses that cause diseases in human and animals Chiu, 2003, Martina et al., 2003. They have the largest genomes in all RNA viruses and replicate by a unique mechanism, which results in high frequency of recombination. Similar to influenza virus, coronaviruses are highly mutable and therefore the infection is extremely difficult to treat (Knipe and Howley, 2001).

RNA interference (RNAi) is a native process in which the introduction of a short double-stranded RNA into cells results in posttranscriptional silencing of the targeted genes. This gene silencing was found to be a gene-specific mechanism for regulation of complex biological functions. RNAi has been successfully used in C. elegans, fungi, Drosophila, and mammalian cells to study gene functions Elbashir et al., 2001a, Elbashir et al., 2001b, Fire et al., 1998, Kadotani et al., 2003. Recently, several reports have demonstrated the use of RNAi for attenuation of viral infection and replication in animal cells, suggesting that RNAi might become a therapeutic approach in the future for treating viral diseases Gitlin et al., 2002, Jacque et al., 2002, Jia and Sun, 2003, Kapadia et al., 2003, Novina et al., 2002, Qin et al., 2003, Randall et al., 2003.

The goal of this study is to test the inhibitory effect of RNAi on the expression of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP) of SARS coronavirus, and the potential of RNAi to attenuate the plaque formation of SARS coronavirus in infected animal cells. Here, we provide the evidence that RNAi targeting at coronavirus RDRP using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression plasmids can specifically inhibit expression of extraneous coronavirus RDRP in 293 and HeLa cells. Moreover, this construct significantly reduced the plaque formation of SARS coronaviruses in Vero-E6 cells. The results may suggest a new approach for treatment of SARS.

Results

Design of specific shRNA expression plasmids targeting at coronavirus RDRP

Coronavirus isolated from SARS patients has a large genomic RNA (approximately 30 kb). When the virus replicates, errors are generated with a high frequency, making the virus particularly difficult to target. We therefore chose the target genes in the viral genome that are conserved in different strains of coronavirus. One of the candidates is RDRP (GeneBank AY 268070). This gene has 645 bp and codes a 215-amino-acid peptide. BLAST analysis shows that there is almost no mismatch in this region of coronaviruses. This sequence has no homology with any known human genes.

Among 25 candidate fragments, five panels of DNA sequences (Table 1) were synthesized and inserted into pSilence1.0-U6. With the U6 pol III promoter, the plasmids express a 55-nt RNA stem-loop. After transfecton, about 40–90% of RDRP gene expression was inhibited, depending on the sequence of the shRNA inserts, based on RT-PCR analysis in both HeLa and 293 cells transfected with RDRP (data not shown). Therefore, we selected the most potent plasmid inserted with sequence A (plasmid-A, see Table 1) for subsequent experiments. A mutated version of the inserted sequence-A with 6-nt mismatch was also synthesized as a specific negative control (plasmid-A*, Table 1).

Table 1.

The sequences of shRNA inserts for pSilence 1.0 U6

| Sequence | Targeting |

|---|---|

| A | 5′-ATCTTAGGATTGCCTACGCttcaagagaGCGTAGGCAATCCTAAGATTTTTTT3′ 24 |

| A* | 5′-ATGTTAGCATTGCCTAGGCttcaagagaGCCTAGGCAATGCTAACATTTTTTT-3′ 24 (mutated bases underlined) |

| B | 5′-TATGACTATGTCATATTCAttcaagagaTGAATATGACATAGTCATATTTTTT-3′ 72 |

| C | 5′-TGTCAACCGCTTCAATGTGttcaagagaCACATTGAAGCGGTTGACATTTTTT-3′ 137 |

| D | 5′-TGTCTGATAGAGATCTTTAttcaagagaTAAAGATCTCTATCAGACATTTTTT-3′ 178 |

| E | 5′-AGGACATGACCTACCGTAGttcaagagaCTACGGTAGGTCATGTCCTTTTTTT-3′ 394 |

shRNA reduced the expression of SARS RDRP mRNA in 293 and HeLa cells

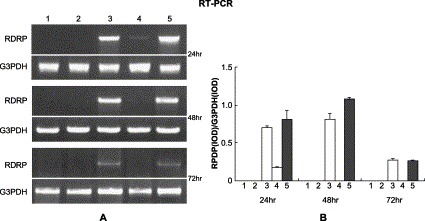

As shown in Fig. 1A , based on the RT-PCR analysis, the expression of extraneous RDRP gene was observed peaking at 48 h after the transfection. When 293 cells were co-transfected with pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP plasmid along with shRNA expression plasmid-A, the RDRP mRNA was reduced to 25% of that of the control cells measured at 24 h after the transfection, and the RDRP mRNA can no longer be detected 48 h after the transfection (Fig. 1B, lane 4). No inhibitory effect was observed in the cells co-transfected with pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP along with plasmid-A* (Fig. 1B, lane 5). The inhibitive effect on RDRP by plasmid-A was also observed in HeLa cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Silencing of the extraneous SARS RDRP gene in 293 cells analyzed by RT-PCR. (A) 293 cells were transfected with pIRES-2-EGFP (lane 1), pIRES-2-EGFP plus pSilence1.0-U6 (lane 2), pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP (lane 3), pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP plus shRNA expression plasmid-A (lane 4), and pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP plus specific mutant plasmid-A* (lane 5), respectively, and measured at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection. (B) The intensity of RT-PCR bands was quantified by Kodak Image Station. These experiments were repeated three times.

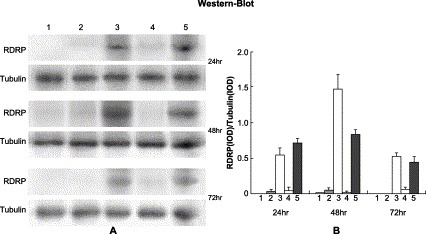

shRNA reduced the production of SARS RDRP proteins

To confirm the effect of shRNA on RDRP expression, we performed Western blot analysis. Because anti-RDRP antibody is not commercially available, antibody against HA tag was used to detect the production of RDRP proteins, in which an HA epitope tag had been introduced at the N-terminus. The results showed that the production of RDRP proteins was reduced by more than 90% in cells co-transfected with plasmid-A (Fig. 2B, lane 4) . The specificity of the RNAi was again demonstrated in that no inhibitory effect on RDRP protein expression was observed in the cells co-transfected with plasmid-A* (Fig. 2, lane 5).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of the expression of extraneous SARS RDRP proteins in 293 cells. (A) 293 cells were transfected with pCMV- HA (lane 1), pCMV-HA plus pSilence1.0-U6 (lane 2), pCMV-HA-RDRP (lane 3), pCMV-HA-RDRP plus shRNA expression plasmid-A (lane 4), and pCMV-HA-RDRP plus specific mutant plasmid-A* (lane 5), respectively, and measured at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection. (B) The intensity of Western blotting bands was quantified by Kodak Image Station. These experiments were repeated three times.

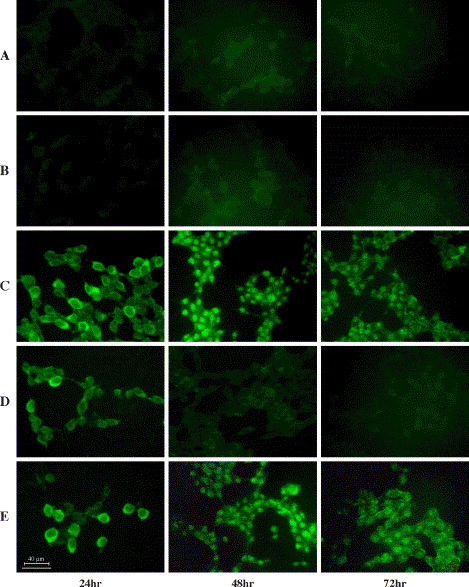

The reduction of RDRP protein in the target cells was also analyzed by immunofluorescence. Again, RDRP production was significantly reduced by plasmid-A (Fig. 3D) , but not by plasmid-A* (Fig. 3E). In addition, we noticed an interesting phenomenon: RDRP proteins appeared to be located in the cytoplasm, but somehow accumulated in the nucleus of the cells 48 h after the transfection (Fig. 3). The significance of this finding is as yet unknown.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of the production of SARS RDRP proteins in 293 cells analyzed by immunofluorescence. 293 cells were transfected with pCMV-HA (A), pCMV-HA plus pSilence1.0-U6 (B), pCMV-HA-RDRP (C), pCMV-HA-RDRP plus shRNA expression plasmid-A (D), and pCMV-HA-RDRP plus specific mutant plasmid-A* (E), respectively, and stained at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection.

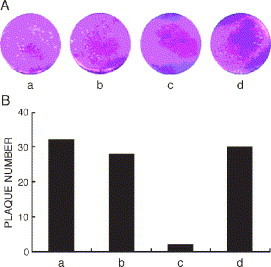

Inhibition of plaque formation of SARS coronavirus in Vero-E6 cells

To test whether shRNA expression plasmid could indeed attenuate SARS coronavirus infection, the plaque formation was analyzed in Vero-E6 cells. Plaques are routinely counted at 48 h after coronavirus infection. No difference in the number of plaques was observed between control cells and cells transfected with either pSilence 1.0-U6 or plasmid-A*. However, the plaque number was significantly reduced in the cells transfected with shRNA expression plasmid-A, indicating that this shRNA expression plasmid could effectively inhibit plaque formation of SARS coronavirus in Vero-E6 cells (Fig. 4) .

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of plaque formation of SARS coronavirus on Vero-E6 cells. (A) Plaque formation in Vero-E6 cells was visualized by staining with crystal violet. Vero-E6 cells were infected with 32 pfu of SARS coronavirus after having been transfected with: (a) no treatment; (b) pSilence1.0-U6; (c) shRNA expression plasmid-A; and (d) the mutant plasmid-A*, respectively. (B) The numbers of plaque formation were counted 48 h after virus infection.

Discussion

The etiologic agent for SARS has been proven to be coronavirus. Because RDRP is the key enzyme for coronavirus replication and its sequences are very conserved in different isolates of coronaviruses, it might be a good target to inhibit the replication of coronavirus in SARS patients.

To test this possibility, in the present study, HeLa cells and 293 cells were transfected with SARS coronavirus RDRP, and the effect of RNAi on inhibition of RDRP of coronavirus was tested. Our data showed that the shRNA expression plasmid for RDRP, plasmid-A, reduced the expression of RDRP in both mRNA and protein levels by more than 90% in both 293 and HeLa cells.

Inhibition of RDRP by the shRNA expression plasmid-A in the RDRP-transfected cells may not necessary to be warranted in cells infected with SARS coronavirus. We therefore tested the inhibition of coronavirus infection by the shRNA expression plasmid-A in Vero-E6 cells infected with the virus. The data clearly demonstrated that the plaque formation of SARS coronavirus was significantly inhibited by this plasmid-A, suggesting the shRNA expression plasmids might indeed inhibit the replication of SARS coronavirus.

Numbers of studies have shown that RNAi is an important mechanism for host defense in plant as well as in mammalian cells Baulcombe, 2002, Ge et al., 2003, Randall et al., 2003, Xia et al., 2002. It has been reported that short interfering RNA (siRNA) worked as antiviral tools in cell culture for HIV, HCV, and herpesvirus Jia and Sun, 2003, Kapadia et al., 2003, Novina et al., 2002, Qin et al., 2003. There have also been reports in regard to treat diseases by siRNA in mice McCaffrey et al., 2002, Song et al., 2003. Delivery of RNAi in those animal studies all depends on a high-pressure injection via mouse-tail vein, which is not practical for humans. Delivery method is therefore a limiting factor for application of RNAi in treating human diseases.

Combined the information together with our study, we therefore proposed that inhibition of RDRP by the shRNA expression plasmid, plasmid-A, might be an anti-coronavirus agent for treating of SRAS patients. In fact, Dr. He et al. most recently reported that siRNA targeting at RDRP could knock down SARS viral genes in FRhk-4 cells (He et al., 2003). Our data not only confirmed their findings, but also provide the new RNAi tool, the shRNA expression plasmids. Considering that the shRNA expression plasmids can be easily incorporated into viral vectors for in vivo delivery, this study may suggest a new method to treat SARS patients in the future.

Methods

Cell culture

Vero-E6, 293, and HeLa cells were routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum.

Plasmid construction

The RDRP gene of coronavirus was synthesized by GeneArt Company (GeneArt GmbH, Rosenberg, Germany) based on the RDRP sequence (GeneBank accession number AY 268070). The synthetic RDRP gene was cloned into KpnI/SacI sites of pCRScript Amp (Stratagene). The RDRP gene was PCR amplified using primers: forward: 5′GCGGAATTCATGCAGGACGCTGTAGCTTC and reverse: 5′GCGGGATCCTCAT AGGTTAT TTTCAGTGTC. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI/BamHI and cloned into mammalian expression vector pIRES-2-EGFP or pCMV-HA that introduced an HA epitope tag at the N-terminus of the proteins. All the inserted sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

shRNA inserts

The shRNA inserts (Table 1) were designed by web-based tools (www.ambion.com/techlib/misc/sirna_finder.html). We designed 25 different pairs of shRNA inserts based on the following criteria: (1) the 19 nucleotides are immediately downstream of an AA di-nucleotide in the coding region of the target gene. (2) The sequence should not contain a repeats of more than four As or Ts. A total five pairs of shRNA inserts were synthesized and inserted into linearized pSilence1.0-U6 (Ambion) according the manufacturer's manual.

Transfection

HeLa and 293 cells were seeded in a 6 well plate at 3 × 105/well the day before transfection. One microgram of RDRP expression plasmids, pIRES-2-EGFP/RDRP or pCMV-HA-RDRP, was co-transfected along with 1 μg of shRNA expression plasmid-A (the best of shRNAs tested) in Lipofectamine 2000 (GibcoBRL), respectively. The plasmids without inserts or the mutant shRNA expression construct, plasmid-A*, was used as negative controls.

RT-PCR

Total RNA from each well of cells was isolated using RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). RT-PCR was carried out with M-MLV kit (GibcoBRL) at 42 °C for 1 h. The reverse transcriptase was then inactivated by heating at 70 °C for 15 min. PCR was performed with 2 μl of cDNA and specific primers: RDRP: forward: 5′GCGGAATTCATGCAGG ACGCTGTAGCTTC3′ and reverse: 5′GCGGGATCCTCATAGGTTATTTTCAGTGTC 3′; G3PDH: forward: 5′ GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT and reverse: 5′GAAGATGTG ATGG GATTTC. PCR was carried out at 95 °C 2 min, then 95 °C 30 s, 55 °C 1 min, 72 °C 1 min for 40 cycles. Five microliters of PCR product were run on a 1% agarose gel.

Western blotting

Cells were harvested at the indicated time after transfection, washed with cold PBS, and total proteins were extracted in the extraction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% glycerol, and 1% NP-40). Protein extracts were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Anti-HA antibodies (Roche), anti-α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies, and HRP-conjugated second antibodies (Chemicon) were used for Western blotting, respectively. Bands were visualized by ECL reagent and recorded on Image Station 440CF (Kodak).

Immunostaining

Cells grown on the glass coverslip were fixed by immersion in 3.7% formaldehyde solution for 30 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were treated in ice-cold methanol/acetone (3:7 v/v) for 15 min at 4 °C. Air-dried coverslips were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere box, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS, and then incubated with primary antibody (1:100 in PBS 1% BSA) for 1 h. After three washes with PBS, the coverslips were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated second antibody (1:100 in PBS 1% BSA) for 30 min, washed with PBS and mounted with 50% glycerol. Photographs were taken on an Olympus immunofluorescent microscope (Model BX51TR) and Apogee Instruments microscopy fluorescence system (Model KX85).

Virus infection

SARS coronavirus (SARS Cov-p9) was kindly provided by the Chinese National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention. The viruses were replicated in Vero-E6 cells at 35 °C. The cell culture supernatant was harvested 48 h after virus infection and stored at −80 °C for future use. To test the anti-SARS virus potential of the shRNA expression plasmids, 1 × 105 Vero-E6 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and transfected with 0.5 μg shRNA expression plasmid-A, its mutant plasmid-A* and another negative control, pSilence1.0-U6, respectively. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the SARS Cov-p9 viruses in the cell culture supernatant mentioned above were diluted at 1/100 000 and added to each well. After infection for 45 min at 35 °C, 1 ml modified Eagle's medium containing 0.8% methylcellulose was added to each well, and the plaques were visualized by staining with crystal violet 48 h after infection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was based on t test and performed on Microsoft Excel. All graphs represent the mean ± SD.

Supplementary Files

Application.

Synthesized SARS RDRP sequence from AY268070:(start and stop codons were added).

Synthesized SARS RDRP sequence from AY268070:(start and stop codons were added).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the Chinese National 973 Project (2001CB510100), 863 Project (2001AA216171), 211 Project (2002–2005), and the grants from Beijing Ministry of Science and Technology (2002–489) and China Medical Board (CMB). We thank Dr. Junqi He and Dr. Biao Kan for their help.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.031.

References

- Baulcombe D. RNA silencing. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:R82–R84. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.T. Taiwanese scientists find genetic link to SARS. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1335. doi: 10.1038/nm1103-1335b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir S.M., Harborth J., Lendeckel W., Yalcin A., Weber K., Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir S.M., Martinez J., Patikaniowska A., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink M., Normile D. Infectious diseases. Search for SARS origins stalls. Science. 2003;302:766–767. doi: 10.1126/science.302.5646.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M.K., Kostas S.A., Driver S.E., Melloc C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Q., McManus M.T., Nguyen T., Shen C.H., Sharp P.A., Eisen H.N., Chen J. RNA interference of influenza virus production by directly targeting mRNA for degradation and indirectly inhibiting all viral RNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:2718–2723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L., Karelsky S., Andino R. Short interfering RNA confers intracellular antiviral immunity in human cells. Nature. 2002;418:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature00873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L., Luo S.W., Li P.H., Zhang L.J., Guan Y.J., Butt K.M., Wong K.L., Chan K.W., Lim W., Shortridge K.F., Yuen K.Y., Peiris J.S., Poon L.L. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M.L., Zheng B., Peng Y., Peiris J.S., Poon L.L., Yuen K.Y., Lin M.C., Kung H.F., Guan Y. Inhibition of SARS-associated coronavirus infection and replication by RNA interference. JAMA. 2003;290:2665–2666. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacque J.M., Triques K., Stevenson M. Modulation of HIV-1replication by RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature00896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q., Sun R. Inhibition of gamma herpesvirus replication by RNA interference. J. Virol. 2003;77:3301–3306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.3301-3306.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadotani N., Nakayashiki H., Tosa Y., Mayama S. RNA silencing in the phytopathogenic fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16:769–776. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.9.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia S.B., Brideau-Andersen A., Chisari F.V. Interference of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by short interfering RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:2014–2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252783999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe D.M., Howley P.M. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. (Field Virology 2001). Chap. 35, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M. SARS virus: the beginning of the unraveling of a new coronavirus. J. Biomed. Sci. 2003;10:664–675. doi: 10.1007/BF02256318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina B.E., Haagmans B.L., Kuiken T., Fouchier R.A., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Van Amerongen G., Peiris J.S., Lim W., Osterhaus A.D. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature. 2003;425:915. doi: 10.1038/425915a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey A.P., Meuse L., Pham T.T., Conklin D.S., Hannon G.J., Kay M.A. RNA interference in adult mice. Nature. 2002;418:38–39. doi: 10.1038/418038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novina C.D., Murray M.F., Dykxhoorn D.M., Beresford P.J., Riess J., Lee S.K., Collman R.G., Lieberman J., Shankar P., Sharp P.A. siRNA-directed inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2002;8:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nm725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X.F., An D.S., Chen I.S.Y., Baltimore D. Inhibiting HIV-1 infection in human T cells by lentiviral-mediated delivery of small interfering RNA against CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:183–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall G., Grakoui A., Rice C.M. Clearance of replicating hepatitis C virus replicon RNAs in cell culture by small interfering RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:235–240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235524100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song E., Lee S.K., Wang J., Ince N., Ouyang N., Min J., Chen J., Shankar P., Lieberman J. RNA interference targeting Fas protects mice from fulminant hepatitis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nm828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Cumulative Number of Reported Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome (SARS) (http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2003_09_23/en/).

- Xia H., Mao Q., Paulson H.L., Davidson B.L. siRNA mediated gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1006–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Velikanov M., Flook P., Zheng W., Szalma S., Kahn S. Assessment of putative protein targets derived from the SARS genome. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:257–263. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01115-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]