Abstract

This article explores global health and the way in which the whole world is increasingly interdependent in terms of health. High-income countries need to help redress the balance of power and resources around the world, for self interest and self preservation if for no other reason. These countries have a particular responsibility to help support the training of more health workers and to strengthen health systems in low-income and middle-income countries. In this interdependent world, high-income countries can learn a great deal from poorer ones as well as vice versa, and concepts of mutuality and codevelopment will become increasingly important.

Keywords: Global health, Health workforce, Codevelopment

Throughout this article the author distinguishes between International Health as a description which has traditionally been used in talking about the health of others—of people and peoples in countries other than our own—and the concept of Global Health, which embraces all those aspects of health shared by us all around the world. There are many of these shared concerns, as we shall see, from global pandemics to climate change and the availability of medicines, and together they reveal how interdependent we all are now in terms of our health.

This article discusses the vital importance to us all of building up the health workforce globally—as just such an example of this interdependence—and argue, further, that those of us living in the richer and more powerful countries of the world have a great deal to learn from people in low-income and middle-income countries who, without our resources and our baggage of history and vested interests, are innovating and developing new ways of tackling the spread of disease and improving health. We need, as argued by the author in the book Turning the World Upside Down,1 to set aside our inbuilt assumptions and unconscious prejudices and see the world differently. We are dependent on each other and we can learn from each other.

Interdependence

Our most obvious interdependence is our shared vulnerability to infectious diseases and the ease with which these can now be transmitted around the world. In the fourteenth century the Black Death took 3 winters to cross Europe, in this century SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) took 3 days to spread across continents. We are all at risk and therefore, one might think, must fight such diseases together. However experience and the emergence of new diseases have shown us that this isn’t at all as straightforward as it might seem. Our shared vulnerability has brought into focus issues of equity and rights.

Globally we need to share our knowledge; this also means sharing the tissues and specimens from ill and deceased people from which we can develop vaccines and treatments. However, as we have seen from recent cases, countries may not be willing to share such materials from their people if they do not believe that their citizens will share in the benefits of the drugs or vaccines developed from them. There is a real and understandable concern that these drugs or vaccines will only be available and affordable in the richer countries and that poorer countries will not get their share of the payback from a joint endeavor. The behavior of governments in both poorer and richer countries comprise test cases of whether countries can work together to counter shared threats, and a test of the will of those in the World Health Organization (WHO) and elsewhere charged with the global governance and improvement of health.

This high-profile and emotive issue can mask a low-profile and equally difficult issue. As readers of this Journal know better than anyone, the diseases that may in time become great pandemics are more likely to arise and gain a foothold from which to spread to areas and countries that have the least developed health and surveillance systems. There is more chance that they will be undetected for longer, possibly misinterpreted and perhaps, even, deliberately hidden. Moreover, there is a greater chance in such relatively weaker and less regulated health systems that our defenses against such diseases will be compromised, with uncontrolled use of drugs allowing multidrug-resistant strains to arise.

In these circumstances we all have an interest in supporting and strengthening the health systems of our neighbors. Our own self interest, let alone any moral sense or feeling of natural justice, means that we can no longer ignore the health problems of the most disadvantaged areas of the world. Issues that might previously have been seen as part of the substance and subject matter of International Health, and worthy subjects for charity and aid, have become real Global Health concerns for us all.

Our interdependence goes far beyond this. Professor Julio Frenk, the former Minister of Health for Mexico and now Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, has identified 7 different types of interdependence, all of which need to shape our understanding of Global Health and our response to our shared problems.2 Here it is worth drawing out 4 categories that go beyond infectious diseases. The first group are the environmental aspects of climate change, pollution, the loss of natural resources and habitats, and overpopulation, which affect us directly in many ways and can, in turn, lead to mass migration, conflict, and disease. The second is the growing incidence of noncommunicable disease, which is increasing in many countries alongside rising wealth and the accompanying change in lifestyles—itself fed by a more global culture that influences our habits—as part of an “epidemiologic transition.” The third is the way in which resources which are costly and in short supply—whether they are trained health workers, equipment, or drugs—are distributed, unequally, around the world.

Sitting alongside these 3 is a fourth category, which has received less attention as yet. It concerns our scientific and medical knowledge and the way in which the traditions of Western Scientific Medicine have been, and are being, shaped and spread around the world by the interests of commerce and academia. The important point here is not criticism, far less repudiation, of science and scientific medicine. Scientific skepticism and objectivity, vide Flexner, is part of the bedrock of health care and health improvement. There is room for a critique, however, of the way particular models of health care systems and academic knowledge and teaching are becoming received wisdom around the world. The ways in which science and professional education have developed in Europe and North America are not necessarily the only valid ways. They require challenge. There are different possibilities and traditions and importantly, as argued here, new traditions are being developed. We have a shared interest in how knowledge is developed, managed, and propagated.

Within our medical ecology as much as in the physical environment, we need to understand that diversity offers us some security and that “monocultures” of knowledge as well as of agricultural practice leave us vulnerable.

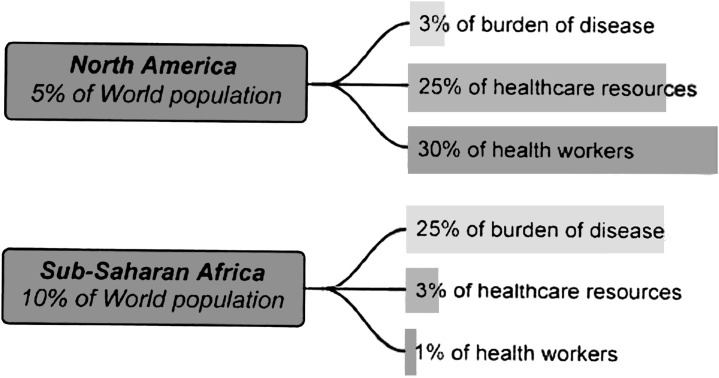

I will return to this topic at the end of this article, but first wish to explore our interdependence in the context of human resources and discuss how the capacity of the health workforce can be built up globally. Like other resources, trained health workers are not distributed evenly or equitably around the world. Fig. 1 contrasts the burden of disease and the availability of resources to tackle it between the richest and poorest continents. Sub-Saharan Africa, with slightly more than 10% of the world’s population, has 25% of the burden of disease; 3% of the world’s health resources and around 1% of the world’s trained health workers deal with this burden. North America, with around 5% of the world’s population, has about 3% of the burden of disease, 25% of the world’s health resources, and 30% of the world’s health workers (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparisons of resources and burdens in the richest and poorest continents.

(From Crisp N. Turning the world upside down—the search for global health in the 21st century. (London): RSM Press; 2010. p. 30; with permission.)

The health workforce

There undoubtedly are important gaps in surveillance in the richest and most developed health systems and countries in the world which need to be addressed; however, they are nothing like as severe or as damaging as the gaps in low-income and middle-income countries. It is important for the safety of us all that health and surveillance systems are strong everywhere. We all have our parts to play.

There is a well-documented shortage of trained health workers globally, with the poorest countries having the greatest shortfalls. The World Health Report for 2006 estimated that there was a global shortfall of at least 4.3 million health workers, and that 57 countries had a critical shortfall.3

First, let us look at the composition of the health workforce in these countries. It is immediately apparent that this is very different from the norm in Europe and the United States. Almost throughout the world, from Pakistan with its Lady Health Workers, Brazil with its rural primary care teams, and Ethiopia with its Health Extension Workers, there has been a large increase in the training and deployment of community health workers. These health workers, based in villages and neighborhoods, are able to deal with health at the most local level in ways that cross the boundaries between clinical care and public health. These workers have different responsibilities in different locations but may typically be concerned with clean water, sanitation, immunization, prenatal care, and the treatment of common conditions with a small range of drugs.

Research has shown that these workers can be effective where they are focused on a few roles or tasks, receive good initial training, undergo some level of supervision and follow-up training, and have the knowledge and ability to refer on to higher trained health workers where necessary.4, 5 Part of their strength is that they are in and of the community, and able to link into a variety of informal community structures as well as the more formal facilities and institutions of the local health services. These community health workers provide the first line of defense against—or, if you prefer, attack on—disease, and have the potential to provide some of the information needed in properly surveying the incidence and spread of disease as well as contributing to its containment and control.

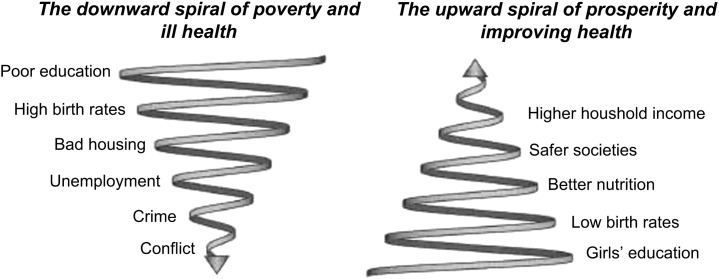

In all too many countries, poverty and everything that is associated with it complicates the situation and leads to poor health, and means that completely inadequate health systems are left to face up to today’s diseases and to tomorrow’s potential pandemics. Health and health care are not stand-alone concepts. Education, housing, and employment are linked to health while strong and vibrant communities are far more resilient in dealing with health and other problems. We know that poor education, high birth rates, unemployment, and social ills such as crime and conflict can contribute to a downward spiral of ill health while improved education (particularly for girls), lower birth rates, safer societies, better nutrition, and growing income can all lead to an upward spiral. Context and community are part of the problem and the solution (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

An illustration of the relationship between poverty and health.

(From Crisp N. Turning the world upside down—the search for global health in the 21st century. (London): RSM Press; 2010. p. 28; with permission.)

In many countries these community health workers are supported by “mid-level workers,” health workers who have been trained in a specific set of tasks or skills important to a country without receiving a full and lengthy professional training. These workers are given a variety of different titles in different countries including clinical officers, tecnicos di cirurgia, and medical officers, and carry out a range of tasks depending on location and priorities, including cesarean sections, trauma, and cataract surgery. They in turn are able to operate most effectively where they have good training and supervision, and are linked in to other more highly trained health professionals. Here again, there is good evidence of how mid-level workers can perform specified tasks to a very high level of competence with, for example, tecnicos di cirurgia in Mozambique performing cesarean sections consistently over several years with as few complications as physicians and at lower cost.6

The crucial point here is that to be truly effective, community health workers and mid-level workers need to be an integral part of a system sharing in its knowledge, training, protocols, referral pathways, and communications. This ideal position is not realized in many areas and many countries where for reasons ranging from political instability, outright conflict, and widespread poverty, there may be fragmented systems or even none at all. In these circumstances a variety of different project-based and ad hoc approaches may be necessary with teams from government, nongovernmental organizations, and development partners all attempting to fill the gaps.

In the longer term, however, the aim must be to build a broadly based community infrastructure connected to both the informal and formal support systems in the community. This linkage will provide the platform for surveillance and disease management in populations as well as better health care for individuals.

The Global Health Workforce Alliance was set up in 2006 as a response to the World Health Report of that year by the WHO and its partners to advocate for the importance of human resource development, and to identify and spread best practice and the findings of research. It, in turn, created several task forces to review and make recommendations in specific areas. In 2007 it established the Task Force on Education and Training, which was charged with identifying how to accelerate massively the education and training of health workers in those countries in crisis.

The Task Force brought together people from different backgrounds and different countries, and was chaired by the Honourable Bience Gawanas (the African Union Commissioner for Social Affairs) and the author. The Task Force studied successful “scaling-up” processes in 10 countries and produced proposals in its 2008 report Scaling Up, Saving Lives 7 on how best to increase the health workforce in all the countries with a critical shortfall. Central to its recommendations was the understanding of the need to produce appropriately trained health workers and a functioning health system. The two go hand in hand.

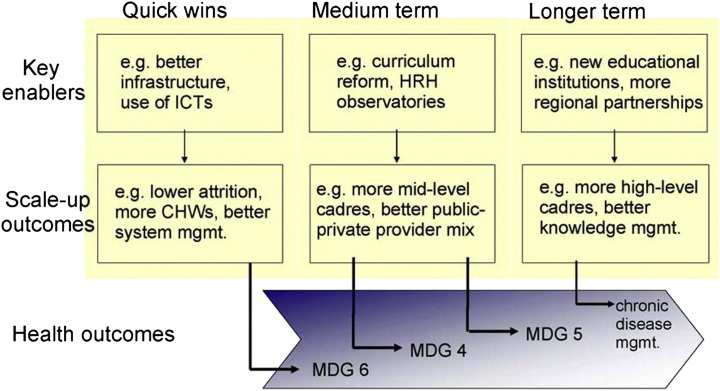

The Task Force concluded that a phased approach was necessary where immediate action could be taken to train more community health workers and reduce attrition from existing training programs. This action would be followed in turn by the longer term training of mid-level workers and the traditional professionals. It would require a good 10 years at least for most countries to become anything like self sufficient in key health workers and to have built up the critical mass of staff and knowledge necessary to support a well-functioning health system. The actual pace at which the workforce could be built up in any country would be determined by the availability of human and financial resources and the supply of employment opportunities for the health workers who had been trained. Fig. 3 offers an overview of the immediate, mid-term, and longer term actions that might be undertaken as part of such a scaling-up process within a country.

Fig. 3.

The 10-year program to build up the health workforce. HRH, Human Resources for Health; MDG, Millennium Development Goals.

The education and training of more health workers is critical for the successful development of an effective health system, but is not sufficient by itself. Emigration of trained health workers from poorer to richer countries, problems of retaining health workers in poorly functioning and badly equipped health facilities, and the lack of money to pay wages all contribute to the difficulties.

At this point it is worth making a temporary excursion into the topic of migration. Migration has been a very damaging phenomenon for many low-income and middle-income countries where a large proportion of recent graduates from nursing and medical schools have left their homelands. At the individual level it is not a simple picture or straightforward story. People have had different motivations to leave. Migration in some cases has been circular—with migrants returning home better equipped to serve the needs of their own countries—and some health workers have moved from one low-income country to another to receive slightly better pay and conditions. The overall picture, however, has been one of movement of trained health workers with their skills and talents moving from poorer environments to richer ones.

The World Health Assembly in May 2010 agreed a Code of Practice8 for migration, which explicitly recognized both the rights of migrants, who may be denied the right to migrate at home and be exploited abroad, and the responsibilities of countries which were currently benefiting or had in the past benefited extensively from the inward flow of expertise and experience. It proposed, among other things, that these receiving countries should recompense the “exporting” countries by supporting the training of more health workers in these countries.

Role of development partners

This discussion takes us on to the role of development partners in supporting the development of effective health systems in countries that lack them. Part of their role is to advocate for the importance of the development of health systems and provide funding for such development, both within the country—where other priorities may prevail—and within the global community. Another part is, of course, to provide humanitarian assistance where countries are in crisis or in conflict. A further major role is to support the pre-service training and education of health workers to increase the supply.

Migration is an important issue. However, it needs to be seen in proportion. The best estimates suggest that about 135,000 health workers from Sub-Saharan Africa who have received their initial training in their home countries have migrated to richer countries over the last 35 years.9 This figure is less than 10% of the shortfall of 1.5 million estimated by the WHO to be needed for the Continent. In numerical terms the biggest problem is that not enough health workers are being trained in the first place.

Several high-income countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, which have benefited from migrant health workers, have excellent traditions of education and training. This is clearly a very significant area where they can and should help by offering assistance to train more health workers in their own countries. This training is happening, but still only in a very patchy and small-scale way.

These development partners also have a role in developing the research, ideas, and technologies that will strengthen health and surveillance systems in countries with few resources of their own. A great deal of international effort is devoted to this from individual governments, international bodies, and philanthropic organizations. While there has been criticism of the slowness of response—and sometimes the lack of fulfillment of promises by donors—we have nevertheless seen the development in recent years of many programs to fund technologies, drugs, and vaccines to address the problems of the poor as opposed to the rich countries and peoples. This social solidarity has benefits for both parties.

Turning the world upside down

Innovation and the development of new ideas is not the sole prerogative of high-income countries. Indeed, as explored by the author in Turning the World Upside Down,1 new ideas and approaches coming from low-income and middle-income countries have the potential to deal with some of the most pressing problems arising in high-income countries. Without the resources and the baggage of tradition and vested interests in rich countries, some people in low-income and middle-income countries are innovating and developing new practices.

There are specific innovations with new low-cost equipment and technologies, and it is no surprise that many of the standard practices in human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS have been developed for and in poorer countries which have suffered most from the condition. Perhaps more importantly, there are general approaches that have been developed, some of which have already been mentioned.

Public health and clinical medicine are brought much closer together. There is far more engagement of the community and of women. Health is not treated as a totally separate issue from education and the ability to earn an income, but rather is considered as part of a person’s ability to function as an independent human being. Many services are delivered by social enterprises that belong neither to the public nor private sector. Most challenging of all, mid-level workers who are trained for specific tasks can, under the right circumstances, perform them as safely and effectively, and less expensively, than multicompetent health professionals.

In high-income countries we are challenged by how to provide effective health promotion, by how to link health and social care, by how to deal with the impacts of poverty and disadvantage on health, and by growing costs. It would no more be appropriate to transfer practices directly and without modification from low-income to high-income countries than the other way round, but we can undoubtedly each learn from the other’s experiences in developing our own new approaches to meet our current challenges.

There is scope for two-way learning and codevelopment, rather than the one-way transfer of knowledge implied in much of the practice and thinking about international development.

The future

These ideas about interdependence and codevelopment are beginning to become more widespread. Many young professionals and students are interested in global health and recognize this interdependence.

These people need to become part of the future education of health professionals, and have already influenced the thinking of the independent Commission on the Education of Health Professionals, which reported in November 2010.10

Interdependence, mutuality of learning, codevelopment, new ideas about service delivery, and professional education are ushering in a new way of looking at the world of Health.

Summary

This article explores the idea of global health and the way in which the whole world is increasingly interdependent in terms of health. It argues that high-income countries need to help redress the balance of power and resources around the world, for self interest and self preservation if for no other reason. These countries have a particular responsibility to help support the training of more health workers and to strengthen health systems in low-income and middle-income countries. The article also argues that in this interdependent world, high-income countries can learn a great deal from poorer ones as well as vice versa, and that concepts of mutuality and codevelopment will become increasingly important.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my researcher, Susana Edjang, for her support with the research for this article, to many audiences over the last year who have engaged me in debate about these ideas and, above all, to my wife Sian for her unfailing support.

Footnotes

Lord Crisp is an independent member of the UK House of Lords, Honorary Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Senior Fellow of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Harvard school of Public Health, and Honorary Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge.

The author has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Crisp N. RSM Press; (London): 2010. Turning the world upside down—the search for global health in the 21st century. p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenk J., Gomez-Dantes O., Chacon F. Handbook of global public health. Routledge; (London): 2010. Global health in transition. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation . World Health Organisation (WHO); May 2006. Working together for better health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haines A., Sanders D., Lehman U. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–2131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douthewaite M., Ward P. Increasing contraceptive use in rural Pakistan: an evaluation of the Lady Health worker Programme. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(2):117–123. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira A., Cumbi C., Malalane R. Meeting the need for emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: work performance and history of medical doctors and assistant medical officers trained for surgery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;114:1253–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Health Workforce Alliance . Global Health Workforce Alliance (GHWA); May 2008. Scaling up, saving lives. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisation. The WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel. World Health Organisation. May, 2010.

- 9.International Labour Office. Report of the Committee of Migrant Workers, Provisional Record 22, 92nd Session. International Labour Conference, Geneva (Switzerland), June 15–17, 2004.

- 10.Frenk J., Chen L., Bhutta Z.A. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]