Abstract

A novel natural rubber/silica (NR/SiO2) nanocomposite is developed by combining self-assembly and latex-compounding techniques. The results show that the SiO2 nanoparticles are homogenously distributed throughout NR matrix as nano-clusters with an average size ranged from 60 to 150 nm when the SiO2 loading is less than 6.5 wt%. At low SiO2 contents (⩽4.0 wt%), the NR latex (NRL) and SiO2 particles are assembled as a core-shell structure by employing poly (diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA) as an inter-medium, and only primary aggregations of SiO2 are observed. When more SiO2 is loaded, secondary aggregations of SiO2 nanoparticles are gradually generated, and the size of SiO2 cluster dramatically increases. The thermal/thermooxidative resistance and mechanical properties of NR/SiO2 nanocomposites are compared to the NR host. The nanocomposites, particularly when the SiO2 nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed, possess significantly enhanced thermal resistance and mechanical properties, which are strongly depended on the morphology of nanocomposites. The NR/SiO2 has great potential to manufacture medical protective products with high performances.

Keywords: Natural rubber, Latex, Silica, Nanocomposite, Self-assembly

1. Introduction

Natural rubber (NR), one of the most important biosynthesized polymers displaying excellent chemical and physical properties, finds widely application in various areas [1], [2], [3]. Particularly, as an chemical-free biomacromolecule, natural rubber latex (NRL) has been used in manufacturing medical products such as medical gloves, condoms, blood transfusion tubing, catheters, injector closures and safety bags due to its excellent elasticity, flexibility, anti-virus permeation, good formability and biodegradability [4], [5], [6]. More recently, with the worldwide spread of the epidemic diseases such as acquired immure deficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis B, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian influenza A (H5N1), it becomes increasingly important and urgent to develop high performance NRL protective products.

However, as its macromolecular backbone incorporates unsaturated cis-1,4-polyisoprenes, NR likes any other polymer is susceptible to oxidative or thermal degradation, particularly when formed into thin films. Once the degradation begins, NR readily becomes tacky and loses mechanical integrity. NRL products have, therefore, short shelf lives and life cycles. Though various anti-ageing agents have been successfully developed for dry NR products and limited anti-ageing agents for NRL were reported by using tris (nonylated phenyl) phosphite [7] and non-water-soluble amino acids [8], no ideal anti-ageing agents have been identified so far for medical NRL products where strict safety and hygiene are required.

Low tensile strength and poor tear resistance are the other major drawbacks encountered in NRL products, especially for medical gloves and condoms. Attempts have been made to use carbon black [9], ultra-fine calcium carbonate [10], modified montmorillonite [11], silica [12] and starch [1] to reinforce dry NR or NRL. However, these traditional reinforcement materials are not so effective for NRL. Therefore, it is essential to exploit new way to enhance the ageing resistance and mechanical properties for NRL products.

Polymeric/inorganic nanocomposites (PINs) represent a radical alternative to conventional-filled polymers or polymer blends, and exhibit a controllable combination of the benefits of polymers (such as flexibility, toughness, and ease of processing) and those of inorganic phase (such as hardness, durability, and thermal stability) [13]. Such an improvement in combined characteristics is particularly significant at low loading levels of nano-fillers, which do not significantly increase the density of the compound or reduce light transmission. Therefore, introduction of inorganic nano-fillers into NR matrixes to overcome the aforementioned disadvantages of NR has recently attracted enormous interest. Most of these are using clay minerals with a unique multi-layered structure to reinforce NR via melt-intercalation [14], [15], latex-compounding [16] and solution-mixing methods [17]. It was found that the organically modified clays with a loading up to 10 wt% have a good reinforcement on the NR matrix due to the intercalation/exfoliation of silicates and formation of a skeleton silicate network in NR matrix [15], [16]. Nair et al. [18], [19], [20] also used nano crab chitin whiskers to reinforce NR. It was found that there is a three-dimensional chitin network within the NR matrix, which results in significantly improved solvent resistance and mechanical properties.

The high reinforcing efficiency of layered silicate rubber nanocompsites, even at low loading of layered silicates, is largely due to the nanoscale dispersion (the thickness of the layered silicates is 1 nm) and the very high aspect ratio of the silicate platelets (length-to-thickness ratio up to 2000). However, using fillers with higher specific surface such as spherical inorganic nanoparticles to directly reinforce NR, which has the potential to further improve the material properties, has not been reported. This is probably because there is no effective process to prevent the strong self-aggregation of nanoparticles.

In our previous work, a novel self-assembly nanocomposite process was developed to prepare a bulk polyvinyl alcohol/silica (PVA/SiO2) nanocomposites [21], [22], [23]. We found that the chemical and physical properties of nanocomposites, compared to the polymer host, were significantly enhanced. The improvement in the properties is largely due to the uniform distribution of SiO2 nanoparticles and the strong interactions between SiO2 and polymer matrixes. We recently extended this self-assembly process to prepare NR/SiO2 nanocomposites and briefly reported its preparation and thermal properties [24]. In the present paper, we will systematically discuss the self-assembly mechanism of the SiO2 and NRL particles, observe the morphology of the nanocomposite and microstructure of SiO2 nano-clusters with SEM and TEM, and investigate the impact of SiO2 on thermal/thermooxidative resistance and mechanical properties.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Natural rubber latex (NRL) with a total solid content of 62% was purchased from Shenli Rubber Plantation (Zhanjiang, PR China), and was pre-vulcanised at room temperature for 2 days with the following formula: sulfur 1.5 parts per hundred rubber (phr); accelerator PX 1.2 phr; accelerator ZDC 0.8 phr; zinc oxide 1.5 phr; and an appropriate amount of stabiliser. Silica nanoparticles (average diameter: 14 nm; surface area: 200 m2/g ± 25 m2/g) and poly (diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA) (mol wt ca. 100,000–200,000; 20 wt% in water) were brought from Sigma–Aldrich (Sigma–Aldrich, Louis, MO). Water was Milli-Q water (18 MΩ-cm). All experimental materials were used as received.

2.2. Preparation of nanocomposite

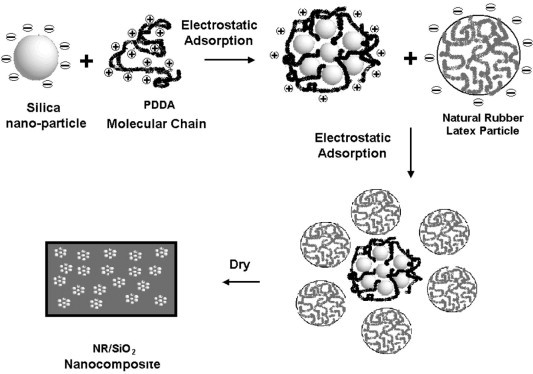

In our previous work [24], we briefly reported a novel process to prepare NR/SiO2 nanocomposites by combining latex-compounding and self-assembly techniques. Firstly, the negatively charged SiO2 nanoparticles act as templates to adsorb positively charged PDDA molecular chains through electrostatic adsorption. Negatively charged NRL particles are then assembled onto the surface of SiO2/PDDA nanoparticles. Finally, the SiO2 nanoparticles are uniformly distributed in NR matrix. The key procedure of this process is the encapsulation of the SiO2 nanoparticles with PDDA and NRL layers, aiming at suppressing the self-aggregation of SiO2 nanoparticle caused by strong particle–particle interactions.

Specifically, the nanocomposites was prepared according to the following procedures. The SiO2 nanoparticle aqueous dispersion of 1 wt% was treated with an ultrasonic vibrator for 0.5 h, and its pH was adjusted to 10 with 0.2 M NaOH to obtain negatively charged SiO2 dispersion. A fixed amount of positively charged PDDA solution (pH 10) with a ratio of PDDA/SiO2 = 5/100 w/w was then dropped into SiO2 dispersion with mechanical stir. To remove PDDA that was not effectively absorbed on the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles and avoid the flocculation of NRL particles cased by the redundant PDDA, the ultrasonically treated SiO2/PDDA dispersion was centrifuged followed by rinsing with Milli-Q water. This step was repeated for 2 times. The rinsed SiO2 particles were then collected and ultrasonically re-dispersed to obtain SiO2/PDDA aqueous dispersion.

A fixed amount of NRL with a total solid content of 5% was treated with an ultrasonic vibrator for 0.5 h, and its pH was adjusted to 10 with 0.2 M NaOH to negatively charge the NRL particles. After that, the rinsed SiO2/PDDA aqueous dispersion was then dropped into NRL with different mixture rates (NR/SiO2 = 99.5/0.5, 99/1.0, 97.5/2.5, 96/4.0, 93.5/6.5 and 91.5/8.5 w/w) accompanying gentle mechanical stir at room temperature to obtain uniform NRL/SiO2 dispersion, which was then dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to obtain NRL/SiO2 nanocomposite films.

2.3. Characterizations

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of the nanocomposites were taken with a Philips XL 30 FEG-SEW instrument (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. The fracture surface was obtained by splitting bulk sample being quenched in liquid nitrogen. A sputter coater was used to pre-coat conductive gold onto the fracture surface before observation. Thin films for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were prepared by cutting bulk samples being quenched in liquid nitrogen. TEM observation was done on a JEM-100CXII instrument (JEOL, Peabody, MA) with an accelerating voltage of 100 KV.

A Perkin–Elmer TGA-7 thermogravimetric analyser (TGA) (Perkin–Elmer, Fremont, CA) was used for thermal and thermooxidative decomposition measurement. In nitrogen, the measurement of the films (ca. 10 mg) was carried out from 100 °C to 600 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min. In air, the TGA analysis was carried out from 100 °C to 700 °C at the same heating rate. The flow rate of the carrying gas is 80 ml/min. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was preformed on a Perkin–Elmer Spectra GX-I FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin–Elmer, Fremont, CA) with a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the transmission mode.

Tensile test and tear resistance experiments were conducted on an Instron Series IX Automated Materials Testing System (Instron, Acton, MA) with a cross head speed of 500 mm/min and the sample length between the jaws was 35 mm, the sample width 10 mm and the thickness 4.5 mm. The measurement was done at room temperature.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Mechanism of self-assembly NR/SiO2 nanocomposite process

When nanoparticles are dispersed with polymers, a core-shell structure tends to be formed in which nanoparticles covered with polymeric chains under certain conditions such as those used for self-assembly. By employing this approach, Caruso et al. [25] developed core-shell materials with given size, topology, and composition. Han and Armes [26] and Rotstein and Tannenbaum [27] studied polypyrrole, polystyrene and silica nanocomposites, respectively, and also confirmed the formation of this core-shell structure. In the present study, SiO2 nanoparticles act as cores or templates to assemble PDDA and then adsorb NRL particles to develop a bulk NR/SiO2 nanocomposite. There are two electrostatic adsorption stages in this process (Fig. 1 ) [24].

Fig. 1.

The schematic of the self-assembly process [24].

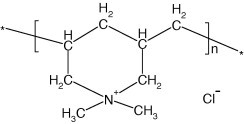

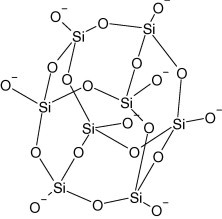

In the first stage, PDDA, an extensively used self-assembling material, is positively charged at the pH of 10 (Scheme 1 ) [28], [29], [30], and is adsorbed onto the surface of negatively charged SiO2 nanoparticles at the same pH (Scheme 2 ) by using the electrostatic adsorption as driving force. However, due to a large difference in rigidity between SiO2 and PDDA and the charge density of PDDA is significantly larger than that on SiO2, all of the former charges cannot form short-distance ion pairs with surface charges of rigid SiO2 particles [30]. Therefore, the positive charge on PDDA cannot completely neutralized by the negative charge on SiO2 particles during the assembly, and the SiO2/PDDA core-shell particles will appear positive and be ready for next assembly with negatively charged NRL particles. To avoid the flocculation of NRL caused by the introduction of high molecular weight water-soluble cationic polyelectrolytes, PDDA that is not effectively assembled with SiO2 is removed by the rinse presented in experimental section.

Scheme 1.

Structure of PDDA at pH of 10.

Scheme 2.

Structure of SiO2 at pH of 10.

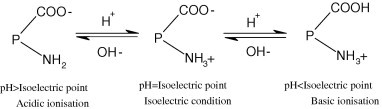

In the second assembly stage, the NRL particles are negatively charged as the protein particles adsorbed on the surface of the NRL particles contain carboxyl and amino functional groups (described as , which can be ionized in three different modes depending on pH value (Scheme 3 ). If the pH is lower than the isoelectric point of NRL (4.5–5.0), basic ionization will occur and NRL particles will be positively charged. Under isoelectric condition, NRL particles will remain neutral. As the pH used in the experiment (pH 10) is higher than the isoelectric point, acidic ionization is generated. NRL particles are, therefore, negatively charged. Again, under the drive of electrostatic adsorption, NRL particles are adsorbed onto the surface of SiO2 particles that are covered with PDDA molecular chains in the previous assembly stage. Finally, the SiO2 nanoparticles covered with PDDA and NRL layers are uniformly dispersed in NR matrix and dried (Fig. 1).

Scheme 3.

Charge mechanism of the NRL particle.

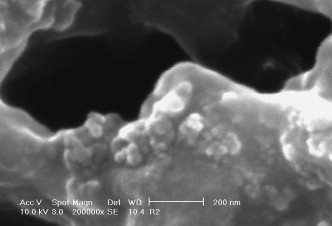

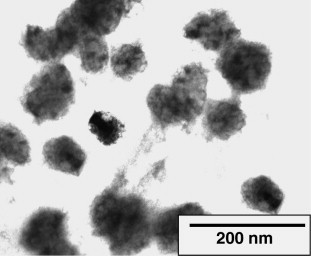

At the first assembly step, the SiO2 nanoparticles act as the core of the SiO2/PDDA core-shell structure. However, the core is not presented as individual SiO2 nanoparticle, but as SiO2 nano-cluster, which is evidenced by the SEM observation (Fig. 2 ), where the spherical nano-cluster and its primary structure unite: single nanoparticles can be clearly observed. This structure is also confirmed by the TEM image (Fig. 3 ), where the solid spherical SiO2 nano-clusters with a diameter around 60 nm (presented as dark circle pies) are uniformly distributed in NR matrix.

Fig. 2.

SEM image of the nano-cluster (4 wt% SiO2).

Fig. 3.

TEM image of nano-cluster (4 wt% SiO2).

According to Rotstein and Tannenbaum [27], the total number of SiO2 primary nanoparticles in a cluster can be approximately estimated as

| (1) |

where N is the maximum number of SiO2 nanoparticles in a cluster with a packing parameter, ε, of 1. R 1 is the radius of the SiO2 nanoparticle (7 nm), and R 2 is the average radius of a cluster that is statistically measured from SEM images by using the following equation:

| (2) |

where N i is the number of the clusters with radius R i. The statistical information of the size distribution and the average radius is summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Size distribution and average radius of SiO2 cluster in NR matrix

| NR/SiO2 | SiO2 content (wt%) | Size distribution (nm) | Average radius (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | 30–100 | 30 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 30–150 | 37.5 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 30–200 | 40 |

| 4 | 4.0 | 30–200 | 42.5 |

| 5 | 6.5 | 30–400 | 75 |

| 6 | 8.5 | 30–2500 | – |

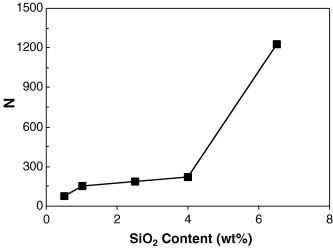

Combining Eqs (1), (2), the average N for each nanocomposite can be obtained (Fig. 4 ). When a small amount of SiO2 (0.5 wt%) is added, the N is around 80, while it gradually increases to 224 as the SiO2 content increases to 4.0 wt%. It is clear that at low loadings the primary aggregations are generated. These primary aggregations are unlikely caused by the strong particle–particle interaction, but the adsorption between polymer molecular chain and SiO2 nanoparticles, i.e. PDDA molecular chains adsorb quite a few separate nanoparticles to form nano-clusters in the stage of assembly. Therefore, the SiO2 is not distributed in NR matrix as individual nanoparticles, but as nano-clusters. Similar assumption was found in polyethylene oxide (PEO)/silica nanocomposites. Gunb’ko et al. [31] reported that each PEO molecules could interact with many primary fumed SiO2 particles to form small aggregates. We also observed this in the PVA/SiO2 nanocomposites during the assembly between PVA and SiO2 nanoparticles [21], [23].

Fig. 4.

The relationship between N and SiO2 content.

However, a pronounced but interesting phenomenon has been observed: the nanoparticles aggregate greatly when the content of the SiO2 nanoparticles is higher than 4 wt% (Fig. 8) and accordingly the size distribution of SiO2 clusters increases significantly (Table 1). It is evident that secondary aggregations based on the primary aggregations are generated at high SiO2 contents. A similar result was also found in PVA/SiO2 nanocomposites where both primary and secondary aggregations were observed at a SiO2 content higher than 5 wt% [21], [23]. However, without further information, we could not explain how and why the strong aggregation starts from this critical level. It will be investigated in our future work, as excessive particle aggregation will generally deteriorate the properties of the composites, and understanding the dispersion and aggregation mechanism during assembly is therefore critical for designing and synthesizing composites with stable behaviors.

Fig. 8.

DTG curves for pure NR and NRL/SiO2 nanocomposites in air.

3.2. Morphology of NR/SiO2 nanocomposites

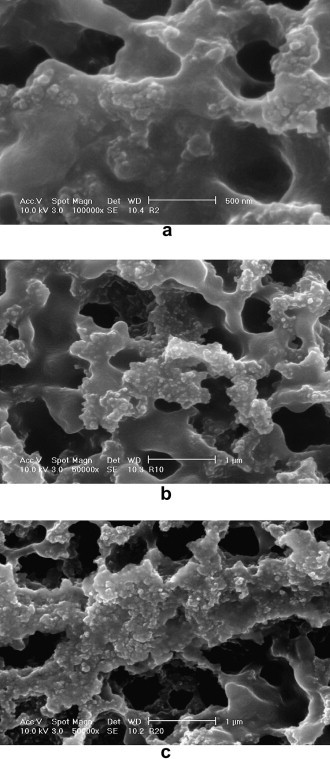

When the SiO2 content is less than 4 wt%, almost all SiO2 nanoparticles are homogenously distributed throughout the NR matrixes as individual spherical nano-clusters, but further increase in the SiO2 content will lead to intensive aggregations. This can be observed from Fig. 5 , which shows the morphology of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposites with different SiO2 contents. The dark phase represents the NR matrix and the bright phase corresponds to the SiO2 particles, which are strongly embedded by NR matrix. The higher the SiO2 content is, the more severe the aggregation can be observed. There is no obvious phase separation observed, implying the good miscibility between NR and SiO2 that are treated with self-assembly process.

Fig. 5.

SEM micrographs of NR/SiO2 nanocomposites: (a) 1.0 wt% SiO2, (b) 4.0 wt% SiO2 and (c) 8.5 wt% SiO2.

When only a very small amount of SiO2 is added to the NR matrix (less than 1.0 wt%), most of the spherical clusters of nanoparticles are individually distributed amongst the NR matrixes (Fig. 5a). When more SiO2 nanoparticles are loaded, the density of the SiO2 clusters becomes higher. The SiO2 clusters start aggregation in some areas for the nanocomposite with the SiO2 content of 4 wt%, where the mixing is not appropriately done (Fig. 5b). When the SiO2 is further increased to 6.5 wt%, the SiO2 clusters are being aggregated in most areas. The aggregation dominates when the SiO2 loading reaches 8.5 wt%. From the SEM micrograph with a lower magnification, the stratiform-like SiO2 aggregation can be clearly observed (Fig. 5c).

From the statistical data, it can be seen that the size of the SiO2 clusters has a very narrow distribution when the SiO2 content is less than 4.0 wt% (Table 1). As more SiO2 is added, the size distribution becomes significantly broader. Similarly, the average diameter of the SiO2 clusters is quite stable (<85 nm) as SiO2 is less than 4.0 wt%, it then markedly increases with the further addition of SiO2. Fumed silica nanoparticles have been extensively used to prepare polymer/silica nanocomposites via melt compounding [32] and other physical blending [33]. However, silica has a number of hydroxyl groups on the surface, which results in the strong filler–filler or particle–particle interactions, and therefore has strong self-aggregation nature. In such conditions, the fumed SiO2 nanoparticles tend to form loosely agglomerates that are dispersed with an average size in the range 300–400 nm, and these aggregated particles cannot be broken down by the shear forces during melt compounding [32]. Compared to other physical blending process, the process in the current work possesses significant advantages, as the size of SiO2 is only around 85 nm.

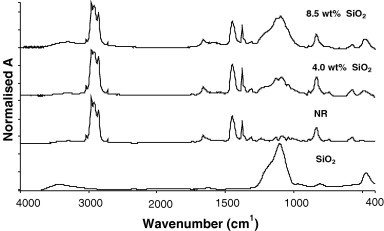

3.3. FTIR study

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) confirms the presence of SiO2 in the NR host, and identifies the interaction between NR and SiO2 phases. As presented in Fig. 6 , in addition to the characterization peaks of NR at 1375 cm−1 and 835 cm−1, the Si–O stretching vibration at 1100 cm−1 and bending vibration at 475 cm−1 [34], [35] are also presented in the spectra of NR/SiO2 nanocomposite, verifying the successful incorporation of the silica nano-structure into NR matrix. The shift of the peak at 3450 cm−1 was frequently used to study the hydrogen bonding between the –OH groups in the SiO2 network and other functional groups from polymer molecular chains [36], [37], and the shift of peak at the 1100 cm−1, and the Si–O bending vibration at 476 cm−1 are the evidence of other interactions. Comparing to other polar rubber/silica systems [38], [39], the above Si–O and –OH vibrating peak of SiO2 shows a less significant shift. This means that the interaction between the NR macromolecular chains and SiO2 is rather low when polar silica is distributed in the non-polar hydrocarbon rubber.

Fig. 6.

FTIR spectra of SiO2, NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites.

3.4. Thermal and thermooxidative ageing resistance

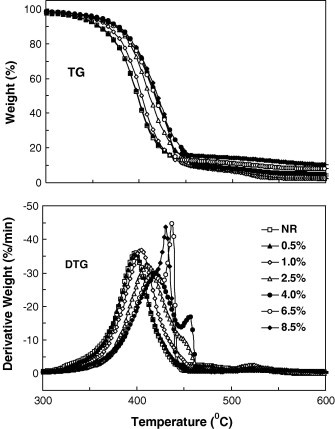

The thermal and thermooxidative ageing resistance of NR/SiO2 nanocomposite can be assessed, respectively, from the investigation of thermal and thermooxidative decomposition. Fig. 7 are the TG and DTG curves of the pure NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites in nitrogen. There is only one obvious thermal decomposition step of NR molecular chains, primarily initiated by thermal scissions of C–C chain bonds accompanying a transfer of hydrogen at the site of scission.

Fig. 7.

TG curves for pure NR and NRL/SiO2 nanocomposites in nitrogen.

The thermooxidative decomposition is obviously different from the thermal decomposition as shown in Fig. 8 , which are the TG and DTG curves of the pure NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites in air, respectively. The first large decomposition peak is caused by oxidative dehydrogenation accompanying hydrogen abstraction, while the second weak peak is resulted from the oxidative reaction of residual carbon. When SiO2 is introduced into NR matrix, the main decomposition peak shifts to a higher temperature and is gradually divided into two peaks. As more SiO2 is added (>6.5 wt%), the side peak becomes sharper, suggesting that the thermooxidative decomposition of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposites should be more complex than that of NR. However, without further information, the role of the SiO2 in the thermooxidative decomposition of NR/SiO2 nanocomposite is not clear. To reveal its thermal and thermooxidative decomposition mechanism, another investigation on thermal and thermooxidative decomposition of NR/SiO2 using thermogravimetry-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (TG-FTIR), and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/massspectroscopy (Py-GC/MS) is being conducted and the results will be reported.

The DTG curve shows the maximum rate of weight loss, so the peak temperatures of decomposition (T p) can be determined. The onset temperatures of decomposition (T o) can be calculated from the TG curves by extrapolating from the curve at the peak of degradation back to the initial weight of the polymer. Similarly, the end temperature of degradation (T f) can be calculated from the TG curves by extrapolating from the curve at the peak of degradation forward to the final weight of the polymer. The temperature range of the thermal degradation, an important parameter to evaluate the degree of degradation, is expressed as ΔT = T p − T o. These characteristic temperatures are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Characteristic temperatures of thermal and thermooxidative decomposition for pure NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites with different SiO2 contents

| Sample | Thermal decomposition |

Thermooxidative decomposition |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tf (°C) | ΔT (°C) | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tf (°C) | ΔT (°C) | |

| NR | 385.0 | 409.9 | 435.4 | 50.4 | 371.0 | 397.6 | 416.2 | 45.2 |

| 0.5% | 386.1 | 411.1 | 436.8 | 50.7 | 371.6 | 397.6 | 417.8 | 46.2 |

| 1.0% | 387.9 | 412.6 | 437.2 | 49.3 | 378.3 | 406.1 | 422.7 | 44.4 |

| 2.5% | 392.6 | 417.8 | 444.8 | 52.2 | 382.3 | 414.6 | 436.0 | 53.7 |

| 4.0% | 395.4 | 420.2 | 447.6 | 52.2 | 384.6 | 419.5 | 438.9 | 54.3 |

| 6.5% | 396.0 | 421.1 | 448.8 | 52.8 | 385.1 | 432.2 | 440.9 | 55.8 |

| 8.5% | 396.2 | 422.6 | 449.3 | 53.1 | 390.2 | 430.7 | 440.7 | 50.5 |

During thermal decomposition, T o, T p and T f all increase with SiO2 content and are relatively stable at the SiO2 content of 4.0 wt%, where T o, T p and T f of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposites increase 10.4 °C, 10.3 °C and 12.2 °C compared to those of the pure NR, respectively.

Similar to the thermal decomposition, T o, T p and T f of NR/SiO2 nanocomposites during thermooxidative decomposition increase 13.6 °C, 21.9 °C and 22.7 °C at SiO2 content of 4.0 wt%, in comparison with those of the pure NR, respectively. In addition, the ΔT for pure NR is smaller than that of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposites, which means the chain scissions for the pure NR last for a shorter time. These significant increases in decomposition temperatures indicate that the thermal and thermooxidative ageing resistance of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposite has been markedly improved.

The thermal and thermooxidative ageing resistance of prepared nanocomposite is dominated by the distribution of SiO2 nanoparticles. Since the SiO2 nanoparticles are homogenously distributed in NR matrix as nano-clusters when SiO2 content is less than 4.0 wt%, the SiO2 and NR molecular chains strongly interact through various effects such as the branching effect, nucleation effect, size effect, and surface effect. Therefore, the diffusion of decomposition products from the bulk polymer to gas phase is slowed down. Consequently, the nanocomposite has a more complex decomposition and a pronounced improvement of ageing resistance compared to the pure NR. With the further addition of SiO2, the self-aggregation of SiO2 is generated due to it being supersaturated and undoubtedly, the interaction density between SiO2 and NR molecular chains decreases. Therefore, the ageing resistance of the nanocomposite cannot be further improved.

Another reason for the improvement in ageing resistance of NR/SiO2 nanocomposites is that inorganic nanoparticles will migrate to the surface of the composites at elevated temperatures because of its relatively low surface potential energy [40]. This migration results in the formation of a SiO2/NR char, which acts as a heating barrier to protect the NR inside. Similar result was found in Gilman [41] and Vyazovkin’s [42] work where a clay/polymer char greatly enhances the thermal resistance of the host polymers.

3.5. Mechanical property

The incorporation of inorganic nanoparticles into elastomer matrix leads to a significant improvement in the mechanical properties of the host elastomer. Table 3 lists the mechanical properties of the pure NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites with different SiO2 loadings. NR, as a typical elastomer, shows an excellent flexibility and low rigidity. Because of the effective reinforcement of SiO2, a dramatic improvement in the tensile strength is found as well as tensile modulus at different elongations. The elongation is just focused on 100%, 200% and 300%, as the filler–polymer interactions play a critical role at a low elongation, while at a high elongation the strain-reduced crystallisation of NR dominates the elongation [15]. The tensile strength and modules increase with the silica loading when less than 4 wt% SiO2 is loaded. Even incorporating a small amount of SiO2 (0.5 wt%) gives a remarkable enhancement in the tensile strength and modules, which reach a peak simultaneously at SiO2 content of 4 wt%. However, with further addition of SiO2, the tensile strength and modules gradually decrease due to SiO2 aggregation.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of pure NR and NR/SiO2 nanocomposites

| SiO2 loading (wt%) | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 6.5 | 8.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength (Mpa) | 15.1 | 18.0 | 19.8 | 22.7 | 26.3 | 21.0 | 1.06 |

| Tensile modulus (Mpa) | |||||||

| 100% elongation | 0.63 | 1.05 | 1.50 | 1.90 | 2.26 | 1.87 | 0.30 |

| 200% elongation | 0.96 | 1.54 | 2.03 | 2.48 | 3.08 | 2.35 | 0.65 |

| 300% elongation | 1.27 | 2.14 | 3.15 | 4.17 | 5.08 | 3.71 | 0.99 |

| Elongation at break (%) | 995 | 963 | 919 | 857 | 730 | 568 | 384 |

| Tear strength (kN/m) | 37.1 | 41.9 | 53.0 | 59.0 | 61.4 | 70.7 | 30.2 |

Another noticeable improvement is observed in tear resistance. Poor tear resistance is one of the major problems for NRL product. Introducing SiO2 into NR can significantly improve its tear resistance. The tear strength increases with an increasing SiO2 loading. At SiO2 content of 6.5 wt%, the tear strength (70.7 kN/m) is almost doubled that of the pure NR (37.1 kN/m). When inorganic nano-fillers are homogenously distributed in polymer matrixes, they will macroscopically form an inorganic network, which mutually penetrates with polymer matrix and restricts the slides of polymer molecules, and therefore increases the mechanical properties of polymer hosts including tear resistance. However, the tear strength receives a significant decrease at the SiO2 content of 8.5 wt%, as severe self-aggregation of SiO2 are generated and the tear resistance of the NR host cannot increase but reduce.

However, the SiO2 reduces the flexibility of NR due to the restriction in the molecular chain slipping along the filler surface. The influence of SiO2 on NR’s elongation at break seems relatively unnoticeable at low SiO2 loading (less than 2.5 wt%), while it plays a critical role at high SiO2. Particularly, the sample with the silica content of 8.5 wt% shows an extremely small elongation at break (384%) compared to that (995%) of the pure NR.

Similar to the thermal resistance, the improvement in various mechanical properties also shows a strong dependence on the morphology of composite. The better the SiO2 dispersion, the better the properties of the nanocomposites as most of the mechanical properties peak at SiO2 loading of 4 wt%, which is the turning point where heavy particle aggregations begin.

4. Conclusions

The self-assembly nanocomposite process has been successfully used to prepare a natural rubber/silica nanocomposite. When SiO2 content is less than 4.0 wt%, by employing PDDA as an inter-medium, the SiO2 nanoparticles are assembled with NRL particles as core-shell structure with slight primary aggregation, and the average size of SiO2 nano-clusters is ranged from 60 to 85 nm. As more SiO2 is loaded, heavy secondary aggregation of SiO2 is gradually generated.

In comparison with pure NR, thermal and thermooxidative ageing resistances of prepared nanocomposite are significantly improved. During the thermal and thermooxidative decomposition, various characteristic temperatures of the NR/SiO2 nanocomposites increase 10–25 °C over those of the pure NR.

The tensile strength, tensile modulus as well as tear strength of the resulting nanocomposite receive markedly increases at SiO2 loadings of 2.5–4 wt%. The influence of SiO2 on NR’s flexibility is relatively samll at low SiO2 loading, while it plays a critical role at high SiO2 in reducing the elongation. The improvement in ageing resistances and mechanical properties are all dominated by the distribution of SiO2 nanoparticles. The better the dispersion of SiO2, the greater the improvement in the thermal and mechanical properties.

Acknowledgement

The financial support by the International Cooperation Project Foundation of Chinese Agricultural Ministry Key Laboratory of Natural Rubber Processing (Grant 706068 and 706069), is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Angellier H., Molina-Boisseau S., Dufresne A. Mechanical properties of waxy maize starch nanocrystal reinforced natural rubber. Macromolecules. 2005;38:9161–9170. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato S., Honda Y., Kuwahara M., Kishimoto H., Yagi N., Muraoka K. Microbial scission of sulfide linkages in vulcanized natural rubber by a white rot basidiornycete, Ceriporiopsis subvermispora. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:511–515. doi: 10.1021/bm034368a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanguansap K., Suteewong T., Saendee P., Buranabunya U., Tangboriboonrat P. Composite natural rubber based latex particles: a novel approach. Polymer. 2005;46:1373–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode H.B., Kerkhoff K., Jendrossek D. Bacterial degradation of natural and synthetic rubber. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:295–303. doi: 10.1021/bm005638h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwerin M., Walsh D., Richardson D., Kisielewski R., Kotz R., Routson L. Biaxial flex-fatigue and viral penetration of natural rubber latex gloves before and after artificial aging. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63:739–745. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh D.L., Schwerin M.R., Kisielewski R.W., Kotz R.M., Chaput M.P., Varney G.W. Abrasion resistance of medical glove materials. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2004;68:81–87. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurian J.K., Peethambaran N.R., Mary K.C., Kuriakose B. Effect of vulcanization systems and antioxidants on discoloration and degradation of natural rubber latex thread under UV radiation. J Appl Polym Sci. 2000;78:304–310. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abad L., Relleve L., Aranilla C., Aliganga A., Diego C.S., Rosa A.D. Natural antioxidants for radiation vulcanization of natural rubber latex. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2002;76:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busfield J.J.C., Deeprasertkul C., Thomas A.G. The effect of liquids on the dynamic properties of carbon black filled natural rubber as a function of pre-strain. Polymer. 2000;41:9219–9225. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai H.H., Li S.D., Rian T.G., Wang H.B., Wang J.H. Reinforcement of natural rubber latex film by ultrafine calcium carbonate. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;87:982–985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arroyo M., Lopez-Manchado M.A., Herrero B. Organo-montmorillonite as substitute of carbon black in natural rubber compounds. Polymer. 2003;44:2447–2453. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jose L., Joseph R. Study of the effect of polyethylene-glycol in field natural-rubber latex vulcanizates. Kaut Gummi Kunstst. 1993;46:220–222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong L.X., Peng Z., Li S.D., Bartold P.M. Nanotechnology and its role in the management of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:184–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teh P.L., Ishak Z.A.M., Hashim A.S., Karger-Kocsis J., Ishiaku U.S. Effects of epoxidized natural rubber as a compatibilizer in melt compounded natural rubber-organoclay nanocomposites. Eur Polym J. 2004;40:2513–2521. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varghese S., Karger-Kocsis J. Melt-compounded natural rubber nanocomposites with pristine and organophilic layered silicates of natural and synthetic origin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;91:813–819. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varghese S., Karger-Kocsis J. Natural rubber-based nanocomposites by latex compounding with layered silicates. Polymer. 2003;44:4921–4927. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magaraphan R., Thaijaroen W., Lim-Ochakun R. Structure and properties of natural rubber and modified montmorillonite nanocomposites. Rubber Chem Technol. 2003;76:406–418. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair K.G., Dufresne A. Crab shell chitin whisker reinforced natural rubber nanocomposites. 1. Processing and swelling behavior. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:657–665. doi: 10.1021/bm020127b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair K.G., Dufresne A. Crab shell chitin whisker reinforced natural rubber nanocomposites. 2. Mechanical behavior. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:666–674. doi: 10.1021/bm0201284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair K.G., Dufresne A., Gandini A., Belgacem M.N. Crab shell chitin whiskers reinforced natural rubber nanocomposites. 3. Effect of chemical modification of chitin whiskers. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1835–1842. doi: 10.1021/bm030058g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng Z., Kong L.X., Li S.D. Non-isothermal crystallisation kinetics of self-assembled polyvinylalcohol/silica nano-composite. Polymer. 2005;46:1949–1955. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng Z., Kong L.X., Li S.D. Thermal properties and morphology of poly (vinyl alcohol)/silica nanocomposite prepared with self-assembled monolayer technique. J Appl Polym Sci. 2005;96:1436–1442. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng Z., Kong L.X., Li S.D., Spiridonov P. Polyvinyl alcohol/Silica nanocomposite: its morphology and thermal degradation kinetics. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:3934–3938. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S.D., Peng Z., Kong L.X., Zhong J.P. Thermal degradation kinetics and morphology of natural rubber/silica nanocomposites. J Nanosci Nanotechno. 2006;6:541–546. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caruso F., Caruso R.A., Mohwald H. Nanoengineering of inorganic and hybrid hollow spheres by colloidal templating. Science. 1998;282:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han M.G., Armes S.P. Preparation and characterization of polypyrrole–silica colloidal nanocomposites in water–methanol mixtures. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2003;262:418–427. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(03)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotstein H., Tannenbaum R. In: Synthesis, functionalization and surface treatment of nanoparticles. Baraton M.-I., editor. American Scientific Publishers; Stevenson Ranch: 2003. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassagneau T., Guerin F., Fendler J.H. Preparation and characterization of ultrathin films layer-by-layer self-assembled from graphite oxide nanoplatelets and polymers. Langmuir. 2000;16:7318–7324. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katagiri K., Caruso F. Functionalization of colloids with robust inorganic-based lipid coatings. Macromolecules. 2004;37:9947–9953. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lvov Y., Ariga K., Onda M., Ichinose I., Kunitake T. Alternate assembly of ordered multilayers of SiO2 and other nanoparticles and polyions. Langmuir. 1997;13:6195–6203. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gun’ko V.M., Zarko V.I., Leboda R., Chibowski E. Aqueous suspension of fumed oxides: particle size distribution and zeta potential. Adv Colloid Interfac. 2001;91:1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S.H., Ahn S.H., Hirai T. Crystallization kinetics and nucleation activity of silica nanoparticle-filled poly(ethylene 2,6-naphthalate) Polymer. 2003;44:5625–5634. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkel T.C., Freeman B.D., Spontak R.J., He Z., Pinnau I., Meakin P. Ultrapermeable, reverse-selective nanocomposite membranes. Science. 2002;296:519–522. doi: 10.1126/science.1069580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito R., Tobe T. Electrical properties of poly(2-vinyl pyridine)/silica nanocomposites prepared with perhydropolysilazane. Polym Adv Technol. 2005;16:232–238. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen L., Zhong W., Wang H.T., Du Q.G., Yang Y.L. Preparation and characterization of SMA(SAN)/silica hybrids derived from water glass. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;93:2289–2296. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X., Wu L., Zhou S., You B. In situ polymerization and characterization of polyester-based polyurethane/nano-silica composites. Polym Int. 2003;52:993–998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong X., Tang T., Zhang Q., Feng Z., Huang B. Polymer/silica nanoscale hybrids through sol–gel method involving emulsion polymers. I. Morphology of poly(butyl methacrylate)/SiO2. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;83:446–454. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glime J., Koenig J.L. FTIR investigation of the molecular structure at the crack interface in unfilled and silica filled polyisoprene. Rubber Chem Technol. 2000;73:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varghese S., Gatos K.G., Apostolov A.A., Karger-Kocsis J. Morphology and mechanical properties of layered silicate reinforced natural and polyurethane rubber blends produced by latex compounding. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;92:543–551. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marosi G., Marton A., Szep A., Csontos I., Keszei S., Zimonyi E. Fire retardancy effect of migration in polypropylene nanocomposites induced by modified interlayer. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2003;82:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilman J.W., Jackson C.L., Morgan A.B., Harris R., Manias E., Giannelis E.P. Chem Mater. 2000;12:1866–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vyazovkin S., Dranca I., Fan X.W., Advincula R. Kinetics of the thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation of a polystyrene–clay nanocomposite. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2004;25:498–503. [Google Scholar]