Abstract

An analysis of the situation of health emergencies in the Western Pacific Region and how the World Health Organization (WHO) has provided support to member states is presented in the paper. Emergency and Humanitarian Action is one of the youngest programmes of the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Despite its organizational size and budgetary limitations, it has endeavored to adequately respond to regional needs for preparedness and response. The paper further looks into approaches for strengthening preparedness, collaboration, and action for disasters and how a community-based approach should offer the best preparedness and response alternative for the region. Examples of country efforts are included. Community-based initiatives are taken as integral components of public health efforts for health emergency management. Thus, public health plays a very crucial role in emergencies.

Keywords: Health emergency management, Western Pacific Region, Disaster management, Training, Community-based programmes, Risk management

1. Introduction

A disaster is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an overwhelming disruption of the ecology of the community that exceeds its capacity to cope with the situation, thereby requiring external assistance. The other important concept is that of an emergency, which is defined as a state in which normal procedures are suspended and extraordinary measures are taken in order to avert the impact of a hazard on a community.

These are important concepts that have to be kept in mind when discussing health emergency management. From a management perspective, it would be better to adopt the concept of emergencies because one would have a better hand on it in terms of management control, in contrast with disasters over which one may not have control.

Using a “disaster” perspective, classification may be just natural disasters or human-generated disasters. However, if one were to look at it from an emergency management perspective, one should look at the typology of hazards: natural hazards, human-generated hazards, and hazards that cause complex emergencies.

Table 1 illustrates the common hazards faced in the Western Pacific Region.

Table 1.

Hazards in the Western Pacific Region

| Type of hazard | Hazards |

|---|---|

| Natural hazards | Sudden impact or acute onset: earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, tsunami, tornadoes, tropical storms, hurricanes, cyclones, typhoons, floods, avalanches, wildfires, cold weather, large-scale outbreaks (e.g., SARS) |

| Slow or chronic onset: drought, famine, environmental degradation, chronic exposure to toxic substances, desertification, pest infestation | |

| Hazards inducing human-generated disasters | Industrial/technological: explosions, fires, system failures/accidents, chemical/radiation, spillages, pollution, terrorism |

| Transportation: vehicular crash, plane crash, ship collision | |

| Deforestation | |

| Material shortage | |

| Hazards inducing complex emergencies | Wars and civil strife, armed aggression, insurgency, and other actions resulting in displaced persons and refugees |

Data from the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs state that, among the 617 natural disasters, 145 or 23.5% of major natural disasters were from the Western Pacific Region. Furthermore, reports from the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters show that, globally, during the last 10 years, 780,000 died, 1.6 million were injured, 82 million lost their homes, and 1.9 billion were affected by natural disasters. From these figures, 8.1% of those killed, 46.8% of those injured, 69.2% of the homeless, and 65.2% of those affected came from the Western Pacific Region.

Historically, the major disasters in the region have been natural disasters: great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Baguio Earthquake of 1990, Mount Pinatubo Eruption of 1991, and the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake of 1995.

The world, however, is in flux and there is a changing threat. Recently, international news reports on weapons of mass destruction, chemical/biological/radionuclear emergencies, terrorism, and armed conflict.

Regarding chemical incidents, Tokyo had a brush with Sarin attacks in 1994. After the attack of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, there was a global panic over the anthrax bacillus, which was spread through the mail.

Then, earlier on this year, the region was affected by the newest emerging disease of the century—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome or SARS. This put the public health system of the various countries to a test. A review of the WHO Western Pacific Region's experience with SARS acknowledged the following as the key elements to the “success” of the fight against SARS in 2003: (1) the high level of leadership and commitment in implementing strong and effective public health interventions; (2) the outstanding dedication and hard work of national and subnational response teams; (3) unprecedented worldwide collaboration among governments and the scientific community; and (4) the praiseworthy willingness of governments to take risks and put health before the economy.

2. Impact of disasters to and response of the health sector

Natural phenomena, such as earthquakes, floods, and typhoons are not disasters but hazards, which may lead to disasters by hitting vulnerable parts of the community that have insufficient readiness/preparedness capacity. Once a disaster occurs, it directly and indirectly affects the health of the people. The health sector, in turn, responds to the impacts of the disasters on the people. However, the health sector may also be affected by the disaster, and if they were not prepared and not able to adequately respond, this would then lead to another indirect impact on the people's health.

Noji points out that the public health infrastructure in developed countries would have the surge capacity to respond to emerging and chronic disasters/health emergencies (Fig. 1) .

Fig. 1.

Public health infrastructure capacity to respond [3].

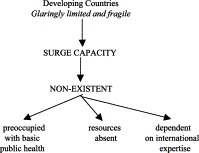

On the other hand, the situation in developing countries is such that the public health infrastructure is “glaringly limited and fragile.” Thus, its surge capacity may be inadequate or, even in certain instances, nonexistent (Fig. 2) .

Fig. 2.

Public health infrastructure capacity in developing countries [3].

To further stress the point, if a big outbreak occurs, a developing country may not be able to cope. To illustrate, if there is a smallpox resurgence that happens in a developed country, there will be a need to increase the number and functions of the following facilities immediately: (1) emergency departments; (2) adequate hospital facilities; (3) vaccination centers; (4) outpatient treatment centers; (5) health information centers; and (5) collecting, clearing, and triage centers. Therefore, how will a developing country be able to set up such a system if its public health system is already strained?

3. Role of the World Health Organization in emergencies and crises

The World Health Organization is a specialized United Nations agency and it is mandated to support member states during health crises. In particular, the WHO Regional Office in the Western Pacific covers 28 states and 9 areas. It has 10 offices for WHO Representatives, five (5) for Country Liaison Officers, and one for the Programme on Technology Transfer. In 1995, the total population of the region was around 1.7 billion.

In the regional office, the Emergency and Humanitarian Action (EHA) Programme is the office that provides support for preparedness and response activities. Ultimately, the regional objective of the EHA Programme in the Western Pacific Region is to ensure a synergy between each component of emergency management and sustainable development in the member states.

At the minimum, the WHO EHA Programme should be able to provide technical support to the member states on preparedness and response activities. National health offices for emergencies/disasters should ensure: (1) information on risks and their determinants; (2) availability of preparedness plans/frameworks; (3) establishment of basic structures—focal points for decisions, human resources, logistics, and health communication/risk communication; (4) early warning systems; and (5) networking and coordination.

On a higher level, activities pursued by WHO should be able to strengthen coordinated public health management, contribute to collective learning, and safeguard health sector accountability. Another very important role would be to ensure WHO's field presence and its operational capacity.

In the WPR, the priority issues on emergency management are the following: (1) recurring and/or increasing hazards; (2) the need to strengthen institutional capacity for emergency management; (3) lack of proactive collaboration among partner agencies; and (4) insufficient health information on emergencies.

For its strategic directions for 2004–2005 biennium, the EHA Programme of the WHO Western Pacific regional office shall focus its resources on: (1) strengthening national capacity building activities for emergency management; (2) assisting countries to develop community-based risk reduction initiatives; (3) providing support to member states in major emergencies; (4) promoting collaboration with partner agencies; and (5) enhancing the WHO's institutional capacity for emergency management.

4. Community-based efforts for public health and emergency management

Primary health care is based on the foundation of building a healthcare system that is community-based, wherein the community members take an active part in management and the pursuit of health development in a sustainable manner.

Public health is defined as “collective action for sustained population-wide health improvement” [1]. It has been apparent that, in any disaster, the community does not only bear the brunt of the immediate effects of the disaster, but it would also have to rely on emergency response efforts because it would take time for external help to arrive on the scene.

There has already been a lot of international experience on this matter, from which some major lessons have been learned [4]:

-

1.

In mass displacement situations, the basic management approach is that of a population-based one and not the management of individuals.

-

2.

In refugee situations, with a huge influx of evacuees, a public health triage system would have to be applied. There would be the need to apply an inclusion and exclusion/prioritization criteria. Basic public health principles of reaching the unreached have to be applied. Even in a refugee camp or an evacuation center, there would be marginalized groups or sites.

-

3.

Early on in the emergency phase, the basic public health services should be restored. There would be a need to reestablish damaged or destroyed utilities, early provision of water and sanitation, and provision of soap, water containers, and health education.

-

4.

Effective emergency/disaster healthcare must be based on accurate information and public health principles. Decisions as to intervention activities must be based on accurate data and health information. There have been various public health rapid assessment tools that have been designed and practice guidelines are readily available.

-

5.

Public health and emergency management has evolved into a specialized field, although one may not be able to claim that it is as sophisticated as clinical specialties or other subdisciplines in public health. There is a greater appreciation now that approaches are more evidence-based.

5. Experiences within the Western Pacific Region

5.1. Viet Nam [2]

This country is highly vulnerable to floods, typhoons, and storm surges (aside from the other natural hazards). Therefore, one effort was to conduct community-based surveys to determine the perception of the causes of the health problems brought about by hazards and what immediate community action could be taken. As a result of the survey, a mass information campaign was conducted, reinforced by training on first aid and swimming.

5.2. Cambodia

The common problems here include typhoons and flooding during the monsoon season. Community-based training was spearheaded by local NGOs and this led to the development of village health volunteers that provided support for preparedness and response activities.

5.3. Philippines

Two community-based disaster preparedness programmes were established by a local foundation, one in an urban setting in Quezon City, which is in metropolitan Manila, and the other one in a rural setting in Carigara, Leyte. The unique feature of this programme was its success in enhancing good collaboration between the local government (which included the politicians), private agencies, and community organizations. The project in the province even led to policy development, wherein a local city ordinance was passed to provide support to community-based efforts in disaster preparedness and response.

5.4. Vanuatu

Local NGOs have conducted community disaster preparedness activities in the form of drama. Some NGOs, like Wan Smolbag, trained youth groups in the performing arts to use drama, song, and dance to increase the awareness of community members on environmental hazards and how to respond to common natural disasters.

6. Conclusion

There have been various initiatives in several countries in the Western Pacific Region to promote community-based efforts in health emergency management. There are still various areas that can be developed and it may be worthwhile for international health agencies like the WHO to provide support to countries by: (1) disseminating information on the best practices for health emergency management; (2) promoting human resource development activities that would strengthen community capacity; (3) promoting projects or programmes on community risk management; and (4) sharing country experiences on community-based efforts for health emergency preparedness and response.

References

- 1.Beaglehole R. Presentation during the Regional Committee Meeting of the WHO Western Pacific Regional Office, Manila, September. 2003. Future of Public Health in the Western Pacific Region. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Van Tuan . Pasteur Institute; Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam: 2003 (October). Personal Correspondence. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noji E. Presentation in the Health Emergencies for Large Populations Course, Fukuoka, March. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toole M. Presentation in the Health Emergencies for Large Populations Course, Fukuoka, March. 2003. [Google Scholar]