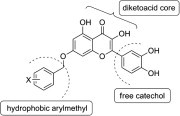

Graphical abstract

An extended feature of the pharmacophore model of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase was proposed which is constituted of a diketoacid core, a hydrophobic arylmethyl substituent, and a free catechol unit.

Keywords: SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), NTPase/helicase, Dihydroxychromone, Pharmacophore

Abstract

Aryl diketoacids have been identified as the first SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase inhibitors with a distinct pharmacophore featuring an arylmethyl group attached to a diketoacid. In order to search for the pharmacophore space around the diketoacid core, three classes of dihydroxychromone derivatives were prepared. Based on SAR study, an extended feature of the pharmacophore model of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase was proposed which is constituted of a diketoacid core, a hydrophobic arylmethyl substituent, and a free catechol unit.

In 2002, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) caused by coronavirus (SARS-CoV) quickly spread to nearly 30 countries leading to infection over 8000 people, and almost 800 deaths worldwide.1 Although new cases of the infection have not been reported since 2004, SARS remains as a global health threat due to its high mortality and lack of therapeutic agents.2

In our previous study,3 we have identified aryl diketoacids (ADKs) as novel anti-SARS agents with selective inhibition (IC50 = 5.4–13.6 μM) against duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase without significant impact on the ATPase activity. It is of particular interest that, among the SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase inhibitors reported to date,3, 4 ADK is the only example with distinct structure–activity relationship to provide an initial feature of the pharmacophore model composed of a diketoacid core with an appropriately positioned arylmethyl substituent (1, Fig. 1 ).

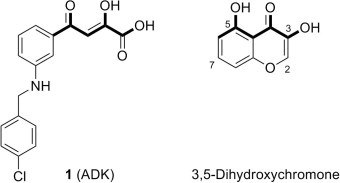

Figure 1.

Comparison of ADK and dihydroxychromone.

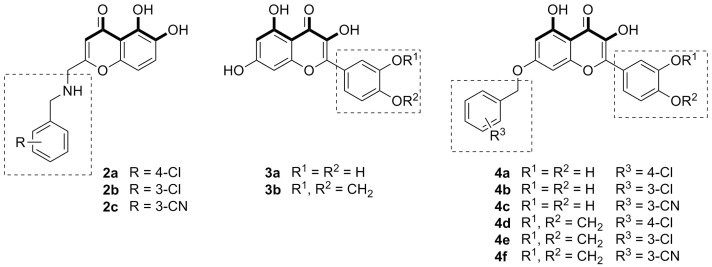

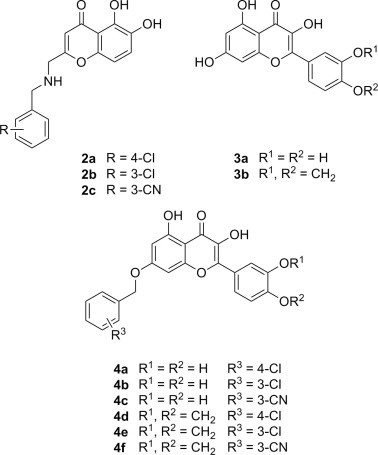

In this study, as a part of our ongoing efforts to delineate a complete pharmacophore model via structural variation on ADK, we designed several dihydroxychromone derivatives as a bioisostere of ADK in which the diketoacid moiety of ADK with poor drug-like property is replaced with a dihydroxychromone scaffold (Fig. 1). Dihydroxychromones, a class of naturally-occurring flavonoids with proven stability and safety,5 share the similar structural motif to the diketoacid of an ADK: two phenolic hydroxyl groups and a carbonyl oxygen serve together as an excellent mimic for the diketoacid functionality (Fig. 1). In addition, compared with an ADK with substituents attached only on one side of the diketoacid, various functionalities can be introduced to both sides of the dihydroxychromone core to allow extended investigation of the pharmacophore space. Thus, we designed novel dihydroxychromone derivatives with an arylmethyl functionality shown to play a critical role in inhibitory activity of ADKs3 as well as a catechol moiety known to be responsible for various biological activities of flavonols6 on either side (2 and 3, Fig. 2 ) or both sides (4, Fig. 2) of the dihydroxychromone scaffold. Herein, we present a novel pharmacophore model of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase inhibitors via syntheses and biological evaluation of three classes of dihydroxychromone derivatives.

Figure 2.

Design of dihydroxychromone derivatives with mono- (2 and 3) and di-substituents (4) on the dihydroxychromone scaffold.

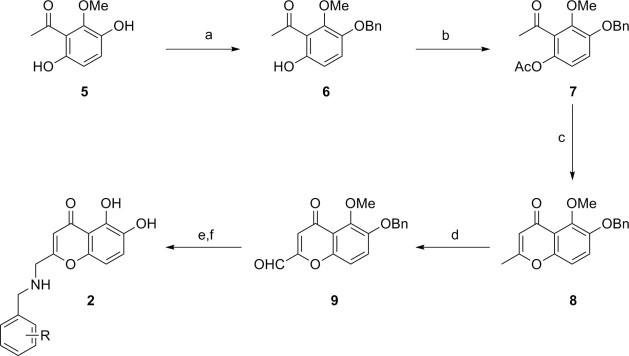

2-[N-(Arylmethylamino)methyl]-5,6-dihydroxychromones (2, Fig. 2) superimposable to ADK were prepared starting from acetophenone 5 (Scheme 1 ).7 Regioselective benzylation of 5 8 followed by acetylation provided the fully protected acetophenone 7 (71% yield for two steps), which underwent cyclization (48% yield) and subsequent oxidation to give the aldehyde 9 in 91% yield. The desired dihydroxychromone derivatives 2a–2c were prepared from the intermediate 9 by reductive amination followed by deprotection with BBr3 in CH2Cl2 (31–38% yield).

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of 2-[N-(arylmethyl)methyl]-5,6-dihydroxy chromone derivatives (2a: R = 4-Cl, 2b: R = 3-Cl, 2c: R = 3-CN). Reagents and conditions: BnBr, K2CO3, acetone, 60 °C; (b) AcCl, Pyr, 60 °C; (c) LiHMDS, THF, −78 °C; (d) SeO2, bromobenzene, 160 °C; (e) (R-Ph)CH2NH2, AcOH, MeOH, NaBH3CN, rt; (f) BBR3, CH2Cl2, rt.

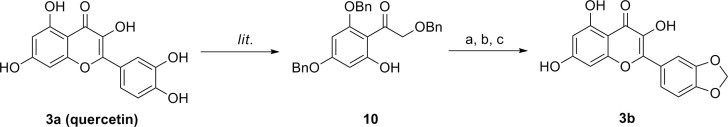

Free or protected catechol was introduced at the other side of the dihydrochromone to give flavonol derivatives (3, Scheme 2 ). The free catechol derivative [quercetin (3a)] was obtained from commercial source and the 3,6-dihydroxychromone derivative with protected catechol functionality at 2 position (3b) was synthesized starting from the phenol 10 which was prepared by degradation of pentabenzylated quercetin9 (65% yield, Scheme 2). Esterification of phenol 10 with piperonyloyl chloride gave the corresponding ester. Cyclization of the ester in the presence of K2CO3 and phase transfer catalyst,10 followed by hydrogenolysis provided the flavonol 3b (72% yield for two steps).

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of 3b from commercially available 3a (quercetin). Reagents and conditions: (a) piperonyloly chloride, Pyr; (b) K2CO3, TBAB, toulene, 90 °C; (c) H2, Pd/C, MeOH/CH2Cl2.

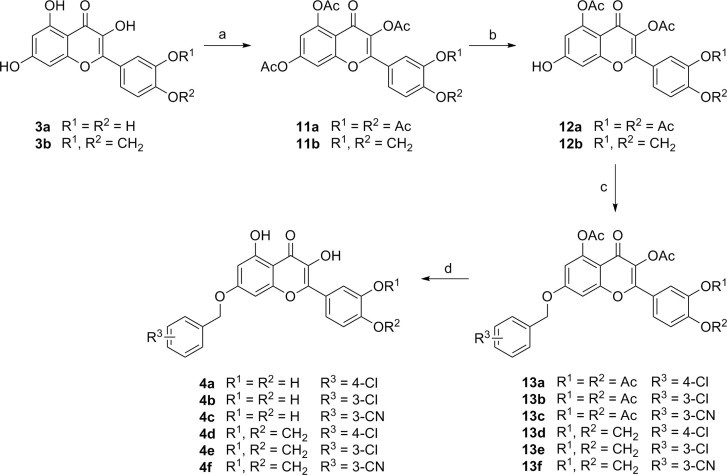

Synthesis of dihydroxychromones with substituents on both sides (4) was accomplished by selective alkylation on 7-O position of the flavonol (3a and 3b) (Scheme 3 ). Thus, peracetylation of 3a (or 3b) followed by selective deacetylation of 7-OAc with thiophenol and imidazole in NMP at 0 °C gave the 7-O-mono deprotected flavonol 12a (or 12b).11 Treatment of 12a (or 12b) with substituted benzyl bromide in acetone in the presence of K2CO3 at room temperature, followed by methanolysis provided the desired compounds 4a–4f in 25–29% yields.

Scheme 3.

Syntheses of dihydrochromone derivatives with substituents on both sides of the core diketoacid mimic. Reagents and conditions: Ac2O, Pyr; (b) PhSH, imidazole, NMP, 0 °C, rt; (c) (R3-Ph)CH2Br, K2CO3, acetone, rt; (d) NH3/MeOH, rt.

The synthesized dihydroxychromone derivatives12 were tested for their inhibitory activities against ATPase and duplex DNA-unwinding activities of the helicase by phosphate release assay13 and FRET-based assay,14 respectively. Cloning and purification of the SARS-CoV helicase were performed as previously described.15

Like ADK analogues,3 dihydroxychromone derivatives showed no significant inhibition against helicase ATPase activity. Only marginal inhibition of the ATPase activity (20.9 and 25.4 μM) was observed with two disubstituted dihydroxychromone derivatives (4a and 4c, Table 1 ). Unexpectedly, compounds 2a–2c, superimposable to the ADK scaffold inhibited neither ATPase nor duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS-CoV ATPase/helicase. Presumably, the high flexibility of (N-arylmethyl)methyl substituent of 2a–2c compared with the ADK counterpart resulted in loss of inhibitory activity.

Table 1.

| Compds | IC50 (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ATPase | Duplex DNA-unwinding | |

| 2a | >50 | >50 |

| 2b | >50 | >50 |

| 2c | >50 | >50 |

| 3a | >50 | 8.1 ± 0.3 |

| 3b | >50 | >50 |

| 4a | 20.9 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| 4b | >50 | 5.2 ± 0.4 |

| 4c | 25.4 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| 4d | >50 | 9.3 ± 0.4 |

| 4e | >50 | 15.4 ± 0.8 |

| 4f | 42.9 ± 5.4 | 8.1 ± 0.3 |

A flavonol with protected catechol group (3b) also failed to show any inhibition against ATPase/helicase. However, a flavonol with free catechol (quercetin, 3a) selectively inhibited the duplex DNA-unwinding activity in micromolar range (IC50 = 8.1 μM, Table 1) to indicate the possible role of the free catechol moiety in the binding interaction with the target enzyme presumably as a hydrogen bond donor.

Interestingly, substitution of arylmethyl functionality on 7-O position of 3b remarkably increased the activity of the resulting compounds (4d–4f, Table 1). The inhibitory activity of quercetin (3a) was also improved upon introduction of arylmethyl substituent at 7-O position (4a–4c, Table 1). It is noteworthy that flavonol derivatives with free catechol moieties (4a–4c) are usually two to three times more active than the protected catechol counterparts (4d–4f). The synergistic effect of the two substituents attached to the opposite side of the dihydrochromone core suggests the presence of two distinct binding sites on the target enzyme: a hydrophobic arylmethyl binding site and a catechol binding site capable of hydrogen bonding interaction.

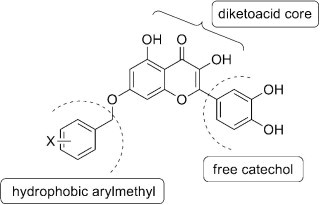

On the basis of this study, we hypothesize an extended pharmacophore model (Fig. 3 ) of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase inhibitors composed of three key components including a diketoacid core, a hydrophobic site and a free catechol moiety.

Figure 3.

The proposed pharmacophore model of SARS-CoV helicase inhibitors.

In summary, in order to investigate the pharmacophore space around the diketoacid core of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase inhibitors, three classes of dihydroxychromone derivatives were prepared in which two different substituents, arylmethyl and catechol, are attached on opposite ends. The synthesized dihydroxychromones showed selective inhibition against duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase. Moreover, the inhibitory activity was enhanced by combination of the two spatially separated substituents, which indicates two different binding sites in the target enzyme. Taken together, an extended feature of the pharmacophore model was proposed which is constituted of a diketoacid core, a hydrophobic arylmethyl substituent, and a free catechol unit. Further structure–activity study around the proposed pharmacophore model is warranted for discovery of more potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A08-4628-AA2023-08N1-00010A), a grant from ORP 11-30-68 (NIAS), and a grant from Biogreen 21 (Korea Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry). Y.-J. Jeong was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2008-313-C00531) and the research program 2009 of Kookmin University in Korea.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.009.

Supplementary data

Experimental section

References and notes

- 1.(a) Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K. Lancet. 2003;361:1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., Berger A., Burguiere A.M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://www.who.int/csr/sars/en.

- 3.Lee C., Lee J.M., Lee N.R., Jin B.S., Jang K.J., Kim D.E., Jeong Y.J., Chong Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:1636. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kliger Y., Levanon E.Y., Gerber D. Drug Discovery Today. 2005;10:345. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03320-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang N., Tanner J.A., Wang Z., Huang J.D., Zheng B.J., Zhu N., Sun H. Chem. Commun. 2007:4413. doi: 10.1039/b709515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kesel A.J. Anti-Infective Agents Med. Chem. 2006;5:161. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spedding G., Ratty A., Middleton E., Jr. Antiviral Res. 1989;12:99. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(89)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Morel I., Lescoat G., Cogrel P., Sergent O., Pasdeloup N., Brissot P., Cillard P., Cillard J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;4:13. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Van Acker S.A.B.E., Van den Berg D.J., Tromp M.N.J.L., Griffoen D.H., van Bennekom W.P., van der Vijjgh W.J.F., Bast A. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1996;20:331. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chiang L.C., Chiang W., Liu M.C., Lin C.C. J. Antimicrob. Chmother. 2003;52:194. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Formica J.V., Regelson W. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1995;33:1061. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash O., Pundeer R., Kaur H. Synthesis. 2003;18:2768. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollenweber E., Iinuma M., Tanaka T., Mizuno M. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:633. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85238-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauteville M., Chadenson M., Chopin J. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1979;11:124. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldwell S.T., Petersson H.M., Farrugia L.J., Mullen W., Crozier A., Hartley R.C. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7257. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M., Han X., Yu B. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:6842. doi: 10.1021/jo034553e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.See Supplementary data for experimental and characterization data for the final compounds (2a–2c, 3b, and 4a–4f) as well as previously unreported intermediates.

- 13.(a) Baykov A.A., Evtushenko O.A., Avaeva S.M. Anal. Biochem. 1988;171:266. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wardell A.D., Errington W., Ciaramella G., Merson J., McGarvey M.J. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin G.R., Yvette M.N., Chrisotomos P., Laurence H.P., Paul W., Wynne A. Anal. Biochem. 2004;327:176. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang K.J., Lee N.R., Yeo W.S., Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;366:738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang N., Tanner J.A., Wang Z., Huang J.D., Zheng B.J., Zhu N., Zun H. Chem. Commun. 2007:4413. doi: 10.1039/b709515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental section