Abstract

This year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine rewards the discoverers of two viruses that cause major afflictions of humankind. Identifying human papilloma virus (HPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) might now appear to have been simple, but the way forward was far from obvious at the time.

Main Text

Fame and tranquillity can never be bedfellows.

—Montaigne (1533–1592)

Virologists, oncologists, and infectious disease physicians are delighted that this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine recognizes the elucidation of the causes of cervical cancer and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). One half of the Prize has been awarded to Harald zur Hausen of the German Center for Cancer Research in Heidelberg for his discovery (while at the University of Freiburg) of “human papilloma viruses causing cervical cancer.” The other half of the Prize is shared between Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier for their discovery of “human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)” at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The key papers were both published 25 years ago (Dürst et al., 1983, Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983).

Some might question why the Nobel Committee coupled HIV with HPV, when no prize can be shared by more than three people. But virus discovery competes with all other areas of medicine, so it is fitting to recognize two of the most important viral pathogens together. HIV-1 and human papilloma viruses of the uterine cervix (HPV-16 and HPV-18) cause immense morbidity and mortality; both are sexually transmitted and both establish life-long, persistent infections. HPV represents a new discovery of an ancient infection whereas HIV-1 is new to humans, the latest data (Worobey et al., 2008) refining Bette Korber's previous estimate of an origin of the pandemic strain 75–100 years ago. The discovery of HPV eventually led to excellent prophylactic vaccines, whereas the discovery of HIV-1 led to effective antiviral drugs but, alas, no safe and efficacious vaccine is yet in sight.

Cervical carcinoma has long been thought to be sexually transmissible. In 1842, one sagacious gentleman of Verona, Domenico Rigoni-Stern, noted that it occurred more frequently among sex workers than nuns. By the 1970s when zur Hausen began his investigations, the chief suspect was herpes simplex virus type II (HSV-II). However, although HSV-II is a sexually transmitted infection, longitudinal studies by Vladimir Vonka and others did not indicate a strong link between this virus and cervical cancer.

Harald zur Hausen came from a herpes virus background, having studied Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) with Gertrude and Werner Henle in Philadelphia. He was the first scientist to develop molecular probes for human viruses, demonstrating in 1970 the presence of EBV DNA in Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. After his return to Germany in 1974, zur Hausen used DNA hybridization and restriction enzyme polymorphisms to initiate the numerical system of HPV typing and to classify HPV strains in plantar and flat warts (HPV-1 to -4). In 1972, an association of papilloma viruses with skin cancer in epidermodysplasia verruciformis had been proposed by Stefania Jablonska in Poland, and in 1978 she and Gerard Orth at the Pasteur Institute discovered HPV-5 in this skin cancer using zur Hausen's methods.

zur Hausen and his young colleagues Herbert Pfister, Lutz Gissman, and Matthias Dürst characterized new strains of HPV. They discovered HPV-6 in condyloma acuminata (genital warts) and also identified a second virus in epidermodysplasia verruciformis, HPV-8. Having cloned these genomes, they used an HPV-6 probe to detect DNA of another strain (HPV-11) in laryngeal tumors, genital condylomas, and a small proportion of cervical cancer specimens. Then they exploited low stringency hybridization to HPV-11 to identify a new genome, HPV-16, present in 11 out of 18 cervical carcinomas (Dürst et al., 1983). The subsequent identification of HPV-18 increased this association and revealed the persistence of HPV-18 in cervical tumor cell lines such as HeLa (Boshart et al., 1984). Further oncogenic strains such as HPV-31 and HPV-45 were detected, and today >99.7% of cervical cancers worldwide are known to carry one or more strains of HPV.

Another classic contribution by zur Hausen's group followed from their observation that HPV-18 frequently becomes integrated into host DNA in tumors (Boshart et al., 1984). They noted that in each case the open reading frames for E6 and E7 are preserved and expressed (Schwarz et al., 1985). This study pinpointed the importance of these genes in carcinogenesis, work that has been greatly extended by Peter Howley and others in the United States, who showed that the oncogenic HPV strains had a high-affinity interaction of viral proteins E6 and E7, respectively, with the p53 and Rb tumor suppressor proteins.

The most important public health outcome of zur Hausen's discovery has been the recent development of vaccines by GlaxoSmithKline and by Merck that prevent infection by the most frequent oncogenic HPV strains (Schiller et al., 2008). The vaccines are highly effective against HPV-16 and -18 and thus can prevent ∼70% of cervical HPV infections. They are based on the self-assembly of the viral capsid protein L1 into virus-like particles pioneered by Doug Lowy and John Schiller at NIH, and by Jian Zhou and Ian Frazer in Brisbane ( Figure 1A).

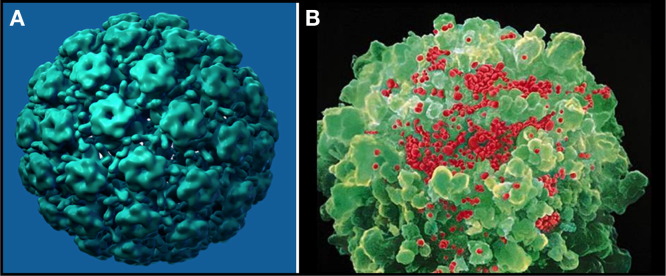

Figure 1.

Viruses in the Spotlight

(A) A model of a virus-like particle of the HPV vaccine in which recombinant L1 proteins assemble into pentamers, which in turn form particles (image courtesy of Mark Feinberg, Merck & Co, Inc.).

(B) HIV particles (artificially colored red) budding from a CD4+ T lymphocyte (image courtesy of David Hockley and Robin A. Weiss).

zur Hausen's success in identifying noncultivatable, new human papilloma viruses by DNA cloning led to the identification by molecular techniques of other human viral pathogens, such as hepatitis C virus in 1989 and Kaposi's sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) in 1994. Unknown and unexpected viruses, such as the SARS coronavirus outbreak in 2003, have been rapidly characterized thanks to modern cloning and sequencing technology. The most recent virus discovery is a new polyomavirus associated with Merkel cell skin cancer in AIDS patients, by Yuan Chang and Pat Moore who also discovered KSHV (Feng et al., 2008).

Human Immunodeficiency Viruses

When AIDS was first reported in a handful of homosexual men in the United States in June 1981, it was not initially clear whether an infection triggered the loss of CD4+ T cells that resulted in immunodeficiency. Other possible causes were proposed, such as recreational drugs or exposure to different human leukocyte antigens from multiple sexual partners. With the observation of AIDS in injecting drug users, and in recipients of blood and blood products, it became evident that a transmissible agent was to blame. In fact, thanks to superb epidemiological investigations at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, by early 1983 we already knew much about the risk factors associated with AIDS; all that was missing was the infective agent itself. Various microbes were mooted, including DNA viruses, RNA viruses, and a fungus secreting an immunosuppressive molecule like cyclosporin.

It was Robert C. Gallo at NIH who first championed the notion that a retrovirus might be the cause of AIDS. His group had recently discovered the first two human retroviruses (HTLV-I and -II). Although I studied these retroviruses, kindly provided by Gallo, I did not consider a retrovirus to be a strong candidate. I thought that a fragile, enveloped virus would not survive the preparation of clotting factors used to treat hemophilia and favored a nonenveloped virus such as a parvovirus—how wrong I was! Then, in the same issue of Science in which Barré-Sinoussi et al. (1983) reported “lymphadenopathy virus” (LAV), Gallo and Max Essex published papers indicating that approximately 10% of AIDS and lymphadenopathy patients were infected with HTLV-I. This was indeed the case, but not the cause; it was analogous to finding HSV-II in a proportion of women with cervical cancer.

The laboratory work at the Pasteur Institute started with a lymph node biopsy provided to Luc Montagnier by Willy Rozenbaum, taken from a homosexual man with persistent lymphadenopathy. Montagnier teased the tissue apart and stimulated the T cells to proliferate in vitro. The cultures did not grow well but were passed on to Françoise Barré-Sinoussi in Jean-Claude Chermann's laboratory. At the time, she was the most experienced retrovirologist at the Pasteur Institute, having worked on murine leukemia virus.

One of Louis Pasteur's best known aphorisms is that “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Barré-Sinoussi proved to be a Pasteurienne par excellence. She observed that the lymphocytes in the culture were not growing but dying, making it exasperatingly difficult to maintain the precious biopsy and requiring the addition of fresh lymphocytes. She realized that an AIDS agent that causes CD4 T cell depletion in vivo might well be cytopathic in vitro. She found that the supernatant contained a filterable agent that could transfer the killing effect to T cells cultured from healthy donors. Moreover, the supernatant contained reverse transcriptase activity (the hallmark of a retrovirus) and the infected cells were bristling with budding virus particles, although they did not have a morphology typical of oncogenic retroviruses (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983).

The observation of a cytopathic retrovirus from a single patient did not make headlines when it was published in May 1983 among the various claims of other putative AIDS agents. Confirmation that this new retrovirus really was the cause of AIDS was cemented by further independent isolations, first by the Pasteur Institute (Vilmer et al., 1984), and then by Gallo's group (Popovic et al., 1984) and by Jay Levy in San Francisco (Levy et al., 1984). Gallo's work in particular convinced the wider research community that a new retrovirus was the genuine culprit. Serological tests were rapidly developed in several laboratories that revealed the high prevalence of infection in various AIDS “risk” groups.

I should admit that I did not take the 1983 French report seriously until 3 months later at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, when Luc Montagnier showed me Charles Dauguet's new electron micrographs of mature retrovirus particles and data on the new isolates derived from the peripheral blood of AIDS patients. Montagnier sent us a virus sample, but we could not propagate it successfully. Later, he suggested trying a laboratory-adapted, more “virulent” stock of virus, and on February 29, 1984 Rachanee Cheingsong brought it from the Pasteur Institute to London. Within 2 weeks, it was producing enormous titers in the CEM T cell line, and these cells became the source of antigen for the Elavia and Wellcozyme diagnostic tests. With hindsight, we know that the first sample we received was the CCR5-tropic HIV isolate Bru, and the high-titer stock was the CXCR4-tropic isolate Lai (Wain-Hobson et al., 1991); Lai was also propagated by Mika Popovic in Gallo's laboratory as HTLV-IIIB.

Each group used a different acronym for their viruses: LAV and IDAV (Montagnier), HTLV-III (Gallo), and ARV (Levy). In 1986, a committee chaired by Harold Varmus coined the name HIV (Essex and Gallo dissenting), which soon became common parlance. Thanks to pre-existing knowledge of retrovirus replication, antiretroviral therapy trials were undertaken in 1986 by Sam Broder and colleagues at the NIH of azidothymidine (Zidovudine), which acts as a chain terminator of reverse transcription. However, owing to the rapid emergence of drug-resistant virus, treatment only became successful when drug combinations were introduced a decade later.

The World Is the Winner

Whereas zur Hausen's contribution undoubtedly towers over HPV, there has been debate about HIV. Initially, the Pasteur Institute scientists were spoken of as a trio, namely Luc Montagnier, Jean-Claude Chermann, and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, but given that the Nobel Committee had a maximum of two names to award for the discovery of HIV, the choice of the 5′ and 3′ authors on the first paper (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983) seems just. At the AIDS Vaccine Conference held in Cape Town a few days after the announcement of the Prize, there was evident satisfaction among the participants that Barré-Sinoussi's crucial contribution had at last been recognized.

The Nobel Committee's scrupulous sifting of nominees is an onerous task and one of the more invidious decisions must be to define the precise field of each year's award. Inevitably, those who champion unsuccessful nominees cry “if only.” If the Committee had decided to recognize human retroviruses, Gallo's discovery of HTLV-I (Poiesz et al., 1980) would stand alongside Barré-Sinoussi's and Montagnier's discovery of HIV. The discovery of HTLV-I came 18 months before the beautiful work of Isao Miyoshi and Yorio Hinuma in Japan, who showed its causal link to adult T cell leukemia. On the other hand, had the Committee been minded to recognize the discovery of human oncogenic viruses, Gallo and Sir Anthony Epstein (who detected EBV in 1964) might have joined zur Hausen. The Committee stated that zur Hausen “went against current dogma and postulated that HPV caused cervical cancer” (although Orth had proposed the same). Likewise, many scientists thought that Epstein and Gallo were wasting their time searching for oncogenic viruses in humans. Either way, Gallo had a near-miss, which he has taken graciously.

Regarding HIV, Gallo's insistence that HTLV-III was a new member of the same family of retroviruses as HTLV-I and HTLV-II confused the field throughout 1984. In contrast, the Pasteur Institute's team was unencumbered by this mindset. Following their first HIV-1 isolate from a patient with lymphadenopathy (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983), they published on further isolates from AIDS patients (Vilmer et al., 1984) and noted their resemblance to a lentivirus (Montagnier et al., 1984) before Gallo and Levy reported their findings. Montagnier's team was also the first to isolate HIV-1 from African patients (Ellrodt et al., 1984) and later discovered HIV-2 in West Africa (Clavel et al., 1986). Nonetheless, it was Gallo's four papers in May 1984 that persuaded the world that the AIDS culprit really had been found. Gallo has continued to provide innovation and insight into HIV-1 and AIDS to this day.

Will there be further Nobel Prizes in virology? I expect so because viruses have provided such penetrating tools to understand the molecular workings of host cells and because viruses will continue to emerge as threats to human health. If we actually attain an effective HIV vaccine through some brilliant new discovery in immunology or virology, I would gladly nominate a second HIV-1 award. However, only one Nobel Prize has been awarded for a viral vaccine, to Max Theiler in 1951 for “his discoveries concerning yellow fever and how to combat it.” To ambitious young investigators, I would say: tackle the big scientific questions but do not chase elusive prizes. One of my mentors (Peter Medawar, Nobel Prize 1960) pointed out that “science is the art of the soluble,” so judging when a problem is ripe for discovery is also important.

From its inception, the choice of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine has been contentious. One could argue that the very first award in 1901 to Emil von Behring for diphtheria serum therapy should have been shared with Shibasaburo Kitasato because the development of antitoxin to tetanus by Kitasato and Behring preceded that of diphtheria; yet the Nobel Committee chose diphtheria alone, probably because it was the more feared disease. The 1902 Prize recognized Ronald Ross for demonstrating in 1898 that avian malaria can be transmitted by mosquitoes but astonishingly (in retrospect) omitted Gianni-Battista Grassi in Italy who contemporaneously identified the mosquito vectors of human malaria. It is a sobering thought that among the 192 Nobel Laureates in Medicine, three at most are household names: Sir Alexander Fleming, Jim Watson, and Francis Crick.

Given that the Nobel Prize for Literature overlooked James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka, and Graham Greene, one might ask, “which virologists are most distinguished by omission?” My first choice would be Friedrich Loeffler, who discovered the first animal virus with Paul Frosch in 1898 (the virus causing foot-and-mouth disease). Previously, Loeffler had discovered the diphtheria bacterium and precisely enunciated the postulates that he ascribed to his mentor, Robert Koch. I wonder about Sir Christopher Andrewes, who identified human influenza virus in 1933. Alick Isaacs, like Proust and Kafka, sadly died too soon after his and Jean Lindermann's discovery of interferon in 1957 to gain recognition. This finding of an innate antiviral response was also the first discovery of a cytokine, long before the interleukins. Perhaps the most notable achievement in overcoming infectious disease during the Nobel era was the eradication of smallpox in 1977 by the WHO team led by Donald Henderson; it cannot qualify for a Nobel Prize in Medicine because it was not a discovery, so a Peace Prize would be apt.

Centenary and Silver Anniversary

One hundred years ago, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to two investigators “in recognition of their work on immunity” who, like this year's winners, worked in France and in Germany. At the Pasteur Institute, the Russian scientist Ilya Mechnikov discovered phagocytosis, while in Berlin and later Frankfurt, Paul Ehrlich delineated humoral and cell-mediated immunity as well as developing chemotherapy, histopathological dyes still in use today, and quantitative methods of biological standardization. It is also the centenary of the demonstration by V. Ellerman and O. Bang in Denmark that a filterable agent could cause leukemia in chickens (that is, the first tumor virus).

The year 1983 was truly a vintage one for pathogen discovery. We have already savored the Freiburg Riesling of HPV and the Pinot Noir Arbois of HIV from Louis Pasteur's own vineyard. It is worth recalling that there was a third discovery, a Swan Valley Shiraz from Western Australia called Helicobacter pylori, for which Barry Marshall and Robin Warren shared the Nobel Prize in 2005. Again, the discovery of H. pylori and its association with peptic and duodenal ulcers, stomach cancer, and later mucosal-associated B cell tumors went against prevailing concepts. There was no strong epidemiological evidence to suggest that these diseases had an infectious etiology. Marshall applied Koch's postulates to himself: he swallowed a pure culture of bacteria and developed severe dyspepsia. It took over a decade for Warren and Marshall to convince physicians (let alone pharmaceutical companies) that inexpensive antibiotics, which eliminate the underlying cause of disease, were more effective than the sophisticated H2-receptor antagonists, which help to control the symptoms.

Conclusion

Discovery is a multistep process in which, as Isaac Newton said, those who see further have stood on the shoulders of giants. It is the really big steps and paradigm shifts that the Nobel Committee rewards. Barré-Sinoussi, Montagnier, and zur Hausen ( Figure 2) have waited 25 years for their fine wines to mature, rather shorter than Peyton Rous's 55 years following his 1911 discovery of Rous sarcoma virus. For me, it has been a privilege to toil in the same vineyards of viral oncology and HIV/AIDS, while witnessing these sparkling discoveries. I warmly toast the Laureates of this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Figure 2.

HPV and HIV Bring Home the Prize

Shown are this year's winners of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine: (left) Harald zur Hausen of the University of Heidelberg and (right) Francoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier of the Pasteur Institute. (Left image courtesy of the German Cancer Research Center; right image courtesy and copyright of Institut Pasteur.)

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to John Moore, Margaret Stanley, and Mark Wainberg for reading a draft, but the opinions expressed are my own.

References

- Barré-Sinoussi F., Chermann J.C., Rey F., Nugeyre M.T., Chamaret S., Gruest J., Dauguet C., Axler Blin C., Vezinet Brun F., Rouzioux C. Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshart M., Gissmann L., Ikenberg H., Kleinheinz A., Scheurlen W., zur Hausen H. EMBO J. 1984;3:1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel F., Guetard D., Brun Vezinet F., Chamaret S., Rey M.A., Santos Ferreira M.O., Laurent A.G., Dauguet C., Katlama C., Rouzioux C. Science. 1986;233:343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.2425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürst M., Gissmann L., Ikenberg H., zur Hausen H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:3812–3815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellrodt A., Barré-Sinoussi F., Le Bras P., Nugeyre M.T., Palazzo L., Rey F., Brun-Vezinet F., Rouzioux C., Segond P., Caquet R. Lancet. 1984;1:1383–1385. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Shuda M., Chang Y., Moore P.S. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J.A., Hoffman A.D., Kramer S., Landis J.A., Shimabukuro J.M., Oshiro L.S. Science. 1984;225:840–842. doi: 10.1126/science.6206563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnier L., Dauguet C., Axler C., Chamanet S., Gruest J., Nugere M., Rey F., Barré-Sinoussi F., Chermann J.-C. Ann. Virol. 1984;135E:119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Poiesz B.J., Ruscetti F.W., Gazdar A.F., Bunn P.A., Minna J.D., Gallo R.C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic M., Sarngadharan M.G., Read E., Gallo R.C. Science. 1984;224:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.6200935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J.T., Castellsagué X., Villa L.L., Hildersheim A. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K53–K61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E., Freese U.K., Gissmann L., Mayer W., Roggenbuck B., Stremlau A., zur Hausen H. Nature. 1985;314:111–114. doi: 10.1038/314111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilmer E., Barré-Sinoussi F., Rouzioux C., Gazengel C., Brun F.V., Dauguet C., Fischer A., Manigne P., Chermann J.C., Griscelli C. Lancet. 1984;1:753–757. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain-Hobson S., Vartanian J.P., Henry M., Chenciner N., Cheynier R., Delassus S., Martins L.P., Sala M., Nugeyre M.T., Guetard D. Science. 1991;252:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.2035026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M., Gemmel M., Teuwen D.E., Haselkorn T., Kunstman K., Bunce M., Muyembe J.J., Kabongo J.M., Kalengayi R.M., Van Marck E. Nature. 2008;455:661–664. doi: 10.1038/nature07390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]