Graphical abstract

Keywords: Dihydropyrimidinones, DHPM, Antiviral activity, Cytotoxicity, Bunyavirus

Abstract

A series of 4-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2-ones (DHPM) was synthesized, characterized by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HRMS spectra. The compounds were evaluated in vitro for their antiviral activity against a broad range of DNA and RNA viruses, along with assessment for potential cytotoxicity in diverse mammalian cell lines. Compound 4m, which possesses a long lipophilic side chain, was found to be a potent and selective inhibitor of Punta Toro virus, a member of the Bunyaviridae. For Rift Valley fever virus, which is another Bunyavirus, the activity of 4m was negligible. DHPMs with a C-4 aryl moiety bearing halogen substitution (4b, 4c and 4d) were found to be cytotoxic in MT4 cells.

Emerging and re-emerging viruses are capable of rapidly overcoming their natural geographical boundaries and spreading among the human population. Most of these viral outbreaks are due to zoonotic viruses, some of which were previously unknown.1, 2 With an increasing risk for vector-borne outbreaks, the Bunyaviridae present a particular and global threat to public health. Members of this virus family are the cause of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome in the Americas and Schmallenberg virus-induced congenital malformations in ruminants, which emerged in Europe in 2011. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious disease caused by the SFTS virus. In addition, some well-known Bunyaviruses like Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus continue to emerge in new geographical locations.3, 4 RVFV is transmitted by a wide variety of mosquitoes and its geographic distribution is expanding, with the potential of reaching Europe in the near future. This virus causes devastating epidemics in Africa and Arabia, killing hundreds of humans and thousands of wild and livestock animals. The transmission of Bunyaviruses, and their cell entry pathways and cell receptors remain poorly characterized, partly due to the fact that experiments with wild-type RVFV are limited to enhanced biosafety level-4 (BSL-4) facilities, which are very few in number.5 The lack of vaccines and antiviral medications makes the potential spread of these Bunyaviruses a global concern. Recently, in an effort to repurpose FDA-approved drugs for RVFV treatment, the anticancer drug sorafenib was found to be an effective inhibitor of RVFV replication.6 Another agent that is able to suppress RVFV replication in cell culture is the polyanionic drug suramin.4, 7

Biginelli condensation is a well-known reaction that is more than 120 years old. It is an exceptionally simple and straightforward acid-catalyzed one-pot cyclocondensation reaction of ethylacetoacetate (1), aldehyde (2) and urea (3) that affords 4-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2-ones (DHPM) or Biginelli compounds.8 A number of variations to give higher yields and expand the scope versus the traditional three-component Biginelli condensation, resulted in many simple derivatives that emerged as promising therapeutic agents. Monastrol was discovered as a prototype anti-cancer drug that inhibits the mitotic kinesin-5 protein.9 Methyl 4-(2-chloro-4-fluorophenyl)-6-methyl-2-(pyridin-2-yl)-1,4-dihydropyrimidine-5-carboxylate (HAP-1) and its derivatives were developed as anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) agents targeting viral capsid assembly.10 Moreover, marine alkaloids Crambescidins and Crambescins containing an DHPM core and isolated from the sponges Crambe crambe and Batzella sp. were demonstrated to possess antiviral and cytotoxic properties.11 Batzelladines A and B with DHPM core were identified as inhibitors of HIV gp-120 binding to CD4 receptors (Fig. 1 ).12 However, the majority of studies exclude or limit the aliphatic aldehydes within their scope due to their troublesome behavior and unacceptable yield in this multi-component reaction.13, 14 It is still desirable to optimize this reaction while employing aliphatic aldehydes.

Fig. 1.

Biologically active DHPMs.

The present work was aimed to synthesize 4-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones using various aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes and evaluate their antiviral activity against a broad range of DNA and RNA viruses, along with their cytotoxicity assessment in diverse mammalian cell lines.

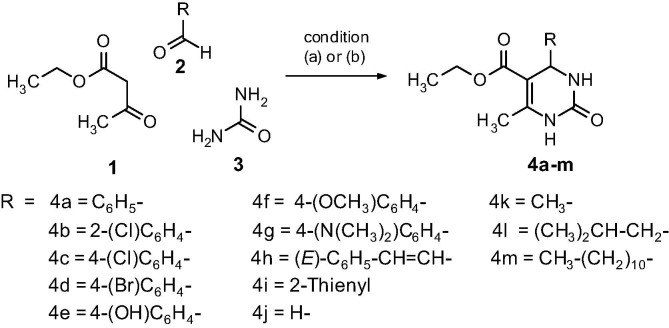

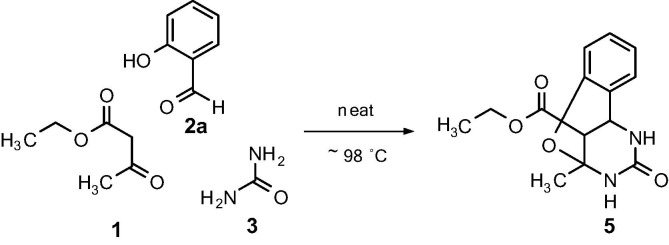

The synthesis of desired compounds is depicted in Scheme 1 . 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2-one bearing C-4 aryl (4a–g; 4i) and styryl (4h) moiety were prepared in excellent yields (83–95%) via neat condition15 without solvent and catalyst at ∼98 °C. Whereas, reaction (Scheme 2 ) employing salicylic aldehyde (2a) in neat conditions, a tricyclic compound i.e. oxygen bridged pyrimidinone (5) was obtained in good yield (76%). However, utilizing aliphatic aldehydes in neat conditions lead to negligible yield of the desired compounds (data not shown). C-4 unsubstituted DHPM (4j) and Dihydropyrimidine-2-one derivatives with C-4 aliphatic group (4k–4m) were achieved by using excess urea under reflux conditions employing acetic acid as a mild acid catalyst in ethanol. The yields ranged from 53 to 68%. All the synthesized compounds were characterized by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HR-MS. (Supplementary data)

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of DHPMs (a) Compounds 4a–i, neat reaction condition at ∼98 °C; (b) Compounds 4j–m CH3COOH, ethanol, reflux.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of oxygen bridged pyrimidinone (5).

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity were determined by previously described methods.16, 17, 18 The compounds plus viruses were added to 96-well plates containing subconfluent cell cultures. After 3–5 days incubation, the virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) was scored which, depending on the virus, consisted of cell lysis, plaque formation, or giant cell formation. Scores of 1, 2, 3 or 4 were given to conditions in which the virus affected 25, 50, 75 or 100% of the cell monolayer, respectively. The virus panel included: (i) evaluated in African green monkey kidney Vero cells: Parainfluenza-3 virus; Reovirus-1; Sindbis virus; Coxsackie virus B4; Punta Toro virus; Rift Valley fever virus (MP-12 strain); and Yellow fever virus; (ii) evaluated in human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblast cells: herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2; varicella-zoster virus; cytomegalovirus; vaccinia virus; and adenovirus; (iii) evaluated in human cervix carcinoma HeLa cells: vesicular stomatitis virus; Coxsackie virus B4; and respiratory syncytial virus; (iv) evaluated in Crandell-Rees feline kidney (CRFK) cells: feline herpesvirus and feline coronavirus; (v) evaluated in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells: influenza A and B virus; (vi) evaluated in human MT-4 T-lymphoblast cells: HIV types 1 and 2. The antiviral activity was assessed based on CPE reduction, as determined by microscopic scoring of the CPE or virus plaque formation. For HIV-1 and -2, the CPE was measured with the colorimetric formazan-based MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2Htetrazolium] assay.

Cytotoxicity of the compounds was assessed by microscopic examination, yielding the minimal cytotoxic concentration (MCC). Alternatively, the colorimetric formazan-based MTS assay was used to determine the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) value.

The antiviral activities and cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds (4a–m and 5) were determined in CPE reduction assays with a broad and diverse panel of DNA and RNA viruses and using relevant mammalian cell lines. The results of the evaluation in Vero cell cultures are presented in Table 1 . Compound 4m was found to be a selective and potent inhibitor of Punta Toro virus (PTV), a member of the family Bunyaviridae and the genus Phlebovirus. 4m was approximately 7 times more potent than the viral entry inhibitor dextran sulphate (DS-10000) and broad-spectrum acting mycophenolic acid (an inhibitor of the cellular IMP dehydrogenase). Compared to the broad antiviral agent ribavirin, 4m proved 17 times more potent with superior activity (EC50 value of 3 μM) and a selectivity index (ratio of 50% cytotoxic concentration to 50% effective antiviral concentration) of ⩾33. The anti-PTV effect of 4m was dose-dependent achieving 81% protection against virus-induced CPE at 20 μM of compound. Since PTV is related to the most clinically relevant Phlebovirus RVFV,19 we next evaluated the effect of 4m against RVFV. This virus is classified as a BSL-4 virus,20, 21 and we therefore used the low-pathogenic MP-12 strain. Although about 40% reduction in RVFV-induced CPE was seen at a compound concentration of 100 μM, 4m was unable to achieve 50% inhibition at this high concentration (data not shown). Also, when evaluated against PTV in HeLa cells, 4m was found to be inactive, which contrasts to the marked effect seen in Vero cells (see above). Hence, the antiviral effect of 4m appears to be cell-dependent, alike what was described for the anti-Ebola virus activity of brincidofovir, an antiviral drug with a lipophilic moiety that is structurally similar to that of 4m.22

Table 1.

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity in Vero cell cultures.

| Compound | Cytotoxicity MCC (μM)a | Antiviral EC50 (μM)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Para-influenza-3 virus | Reovirus-1 | Sindbis virus | Coxsackie virus B4 | Punta Toro virus | Yellow fever virus | ||

| 4a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4b | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4c | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4d | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4e | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4f | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4g | 100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4h | 100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4i | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4j | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4k | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4l | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4m | ⩾100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 3.0 ± 1.4e | >100 |

| 5 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| DS-10,000c | >100 | >100 | >100 | 20 | 58 | 20 | 0.8 |

| Ribavirin | >250 | 112 | >250 | >250 | >250 | 50 | 112 |

| MPAd | >100 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 4 | >250 | 20 | 4 |

MCC: minimal cytotoxic concentration, or compound concentration producing minimal alterations in cell morphology, as detected by microscopical inspection.

EC50: 50% effective concentration, or compound concentration giving 50% protection against virus-induced cytopathic effect, as determined by microscopy.

DS-10,000: dextran sulphate of MW 10,000; these data are expressed in μg per ml.

MPA: mycophenolic acid.

Mean ± SD of two independent tests.

Among the DHPM series that we synthesized, the distinguished structural feature of 4m is its very long lipophilic chain at position C-4 of the polar dihydropyrimidinone scaffold, leading us to assume that the observed anti-PTV activity mainly depends on the undecyl moiety which confers amphiphilic properties to 4m. Some amphiphilic molecules with a large polar head group (inverted-cone-shaped) are known to target viral membranes and display broad-spectrum antiviral activity.23 However, except for Punta Toro virus, 4m did not have antiviral activity against all other viruses tested. This molecule displayed only modest cytotoxicity (Table 2 ), with a minimal cytotoxic concentration (MCC) of 100 μM in Vero and human embryonic lung (HEL) cells, and no toxicity at 100 μM compound concentration in the other cell lines tested. Human MT4 T-lymphoblast cells were an exception with a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of 50 μM. Of the other DHPM compounds tested, none had noticeable antiviral activity. Compound 4h had marginal activity against varicella zoster virus (EC50 of 57 μM and MCC of 100 μM). Compounds 4b, 4c and 4d displayed no antiviral activity yet some cytotoxicity in MT-4 cells.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity in diverse mammalian cell lines.

| Compound | Cytotoxicity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC (μM)a |

CC50 (μM)b |

|||||

| Vero | HeLa | MDCK | HEL | CRFK | MT-4 | |

| 4a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4b | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 96 |

| 4c | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 76 |

| 4d | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 64 |

| 4e | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4f | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4g | 100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4h | 100 | ⩾100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4i | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4j | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4k | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4l | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

| 4m | ⩾100 | >100 | >100 | 100 | >100 | 50 |

| 5 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >125 |

The following cell lines were used: Vero, African green monkey kidney cells; HeLa, cervix carcinoma cells; MDCK, Madin-Darby canine kidney cells; HEL, human embryonic lung fibroblast cells; CRFK, Crandell-Rees feline kidney cells; MT-4, human T-lymphoblast cells.

MCC: minimal cytotoxic concentration, or compound concentration producing minimal alterations in cell morphology, as detected by microscopical inspection.

CC50: 50% cytotoxic concentration, determined by the colorimetric and formazan-based MTS cell viability test.

In summary, an efficient reaction condition was developed for utilizing aliphatic aldehydes in biginelli condensation. Ethyl 6-methyl-2-oxo-4-undecyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-5-pyrimidinecarboxylate (4m) displayed selective and potent antiviral activity against Punta Toro virus. Based on these first results, further evaluation of 4m against other Bunyaviruses (such as Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus) is warranted. Also, mechanistic studies are underway to understand the biochemical basis for its antiviral effect against Punta Toro virus.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge excellent technical assistance from Leentje Persoons, Frieda De Meyer, Lies Van den Heurck, Kristien Erven and Jasper Rymenants. We thank Richard Elliott (University of St Andrews, UK) for providing the RVFV MP-12 strain. This work was supported by the Flemish Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) via the Infect-ERA EScential network.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.010. These data include MOL files and InChiKeys of the most important compounds described in this article.

A. Supplementary data

MOL files

The following ZIP file contains the MOL files of the most important compounds referred to in this article.

ZIP file containing the MOL files of the most important compounds in this article.

References

- 1.Jones K.E., Patel N.G., Levy M.A. Nature. 2008;451:990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zappa A., Amendola A., Romanò L., Zanetti A. Blood Transfusion. 2009;7:167–171. doi: 10.2450/2009.0076-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott R.M., Brennan B. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;5:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiao L., Ouyang S., Liang M. J Virol. 2013;87:6829–6839. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00672-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendenhall M., Wong M.-H., Skirpstunas R., Morrey J.D., Gowen B.B. Virology. 2009;395:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedict A., Bansal N., Senina S. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:676. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellenbecker M., Lanchy J.-M., Lodmell J.S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:7405–7415. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03595-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver Kappe C. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:6937–6963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haque S.A., Hasaka T.P., Brooks A.D., Lobanov P.V., Baas P.W. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:10–16. doi: 10.1002/cm.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X., Zhao G., Zhou X. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blunt J.W., Munro M.H.G., editors. Dictionary of Marine Natural Products with CD-ROM. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Taylor & Francis Group; USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patil A.D., Kumar N.V., Kokke W.C. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappe C.O. Eur J Med Chem. 2000;35:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)01189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappe C.O. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:879–888. doi: 10.1021/ar000048h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranu B.C., Hajra A., Dey S.S. Org Process Res Dev. 2002;6:817–818. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naesens L., Vanderlinden E., Rőth E. Antiviral Res. 2009;82:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderlinden E., Göktas F., Cesur Z. J Virol. 2010;84:4277–4288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02325-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pannecouque C., Daelemans D., De Clercq E. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefan C.P., Chase K., Coyne S., Kulesh D.A., Minogue T.D., Koehler J.W. Virol J. 2016;13:54. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolin A.I., Berrang-Ford L., Kulkarni M.A. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e81. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dar O., McIntyre S., Hogarth S., Heymann D. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:189–193. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.120941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMullan L.K., Flint M., Dyall J. Antiviral Res. 2016;125:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vigant F., Santos N.C., Lee B. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ZIP file containing the MOL files of the most important compounds in this article.