Abstract

Objective

Fenestrated and branched endovascular devices are increasingly used for complex aortic diseases, and despite the challenging nature of these procedures, early experiences from pioneering centers have been encouraging. The objectives of this retrospective study were to report our experience of intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) during fenestrated and branched stent grafting and to analyze the impact on clinical outcomes.

Methods

Consecutive patients treated with fenestrated and branched stent grafting in a tertiary vascular center between February 2006 and October 2013 were evaluated. A prospectively maintained computerized database was scrutinized and updated retrospectively. Intraoperative angiograms were reviewed to identify IOAEs, and adverse events were categorized into three types: target vessel cannulation, positioning of graft components, and intraoperative access. Clinical consequences of IOAEs were analyzed to ascertain whether they were responsible for death or moderate to severe postoperative complications.

Results

During the study period, 113 consecutive elective patients underwent fenestrated or branched stent grafting. Indications for treatment were asymptomatic complex abdominal aortic aneurysms (CAAAs, n = 89) and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAAAs, n = 24). Stent grafts included fenestrated (n = 79) and branched (n = 17) Cook stent grafts (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind), Ventana (Endologix, Irvine, Calif) stent grafts (n = 9), and fenestrated Anaconda (Vascutek Terumo, Scotland, UK) stent grafts (n = 8). In-hospital mortality rates for the CAAA and TAAA groups were 6.7% (6 of 89) and 12.5% (3 of 24), respectively. Twenty-eight moderate to severe complications occurred in 21 patients (18.6%). Spinal cord ischemia was recorded in six patients, three of which resolved completely. A total of 37 IOAEs were recorded in 34 (30.1%) patients (22 CAAAs and 12 TAAAs). Of 37 IOAEs, 15 (40.5%) resulted in no clinical consequence in 15 patients; 17 (45.9%) were responsible for moderate to severe complications in 16 patients, and five (13.5%) led to death in four patients. The composite end point death/nonfatal moderate to severe complication occurred more frequently in patients with IOAEs compared with patients without IOAEs (20 of 34 vs 12 of 79; P < .0001).

Conclusions

In this contemporary series, IOAEs were relatively frequent during branched or fenestrated stenting procedures and were often responsible for significant complications.

Fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repairs (FEVAR and BEVAR) have become an attractive alternative to open repair for complex abdominal aortic aneurysms (CAAAs) and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAAAs). In many countries, these complex procedures are still under evaluation and generally available only in tertiary centers. In France, fenestrated and branched Cook devices have been approved for reimbursement from the national health care system. However, intraoperative difficulties and complications are not rare.1 Safe target vessel cannulation and stenting is a concern, particularly in the presence of stenotic ostial lesions and small or angulated target vessels. Malpositioning of stent graft components can also have devastating consequences. As delivery devices are larger than in standard infrarenal endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and the procedure duration is generally longer, patients are more prone to access complications. The real incidence of those intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) and their impact on the postoperative course are poorly documented.

In this retrospective study, we report the incidence of IOAEs during fenestrated or branched stent grafting and analyze to what extent these adverse events may influence early postoperative outcomes.

Methods

Study setting

Consecutive patients undergoing FEVAR or BEVAR between February 2006 and October 2013 in a tertiary vascular unit (Henri Mondor Hospital, Créteil) were included. Patients were treated for CAAAs and TAAAs. CAAAs included short-necked infrarenal, juxtarenal, pararenal, and suprarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms, considered unsuitable for conventional EVAR. TAAAs were classified according to the Crawford classification.2 In our institution, all patients with CAAAs and TAAAs are considered for open, hybrid, or endovascular repair in a multidisciplinary meeting including vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, and anesthesiologists. Demographic, anatomic, intraoperative, and postoperative data were recorded by means of a prospectively collected database.

Preoperative assessment and device sizing

All patients underwent a high-resolution computed tomography scan preoperatively and before discharge. Procedure planning and device sizing were performed with a dedicated three-dimensional vascular imaging workstation (Aquarius WS; TeraRecon Inc, Mateo, Calif) with centerline luminal reconstructions. The aneurysm morphology was assessed by a vascular surgeon (M.M.) and an interventional radiologist (H.K.), both with considerable experience with EVAR. Device designs proposed by the implanting physicians were systematically reviewed and approved by the planning center of the corresponding device manufacturer.

Details of procedures

Procedures were performed in an angiography suite (Philips FD20; Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, Ohio) in a sterile environment. An experienced proctor physician was present during the procedure for the first five Cook fenestrated cases, the first two Cook branched cases, and the first fenestrated Anaconda and Ventana cases. Eight physician-modified fenestrated stent grafts were excluded. For each device, the implantation techniques have been described previously.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Control angiograms were obtained once each target vessel was cannulated with a long sheath, after deployment of bridging covered stents in each target vessel, and at the end of the procedure. Each control angiogram was saved and images were stored in a database. Technical problems and subsequent IOAEs were also recorded in the database.

Definitions

IOAEs were defined as any intraoperative complication or technical problem occurring during stent graft implantation that required additional and unexpected endovascular manipulations. IOAEs were classified in three distinct types:

Type 1: Problems with target vessel cannulation;

Type 2: Malpositioning of one of the following graft components: bridging stents, bifurcated component, or iliac extensions; and

Type 3: Difficulty with intraoperative access.

Complications were defined according to the Society for Vascular Surgery criteria.10 Only moderate and severe complications were reported in the current series.

Study protocol

A radiologist (H.K.) and a vascular surgeon (F.C.) reviewed intraoperative and postoperative data recorded in the prospectively maintained FEVAR or BEVAR database and all intraoperative angiograms for each patient to identify IOAEs. Both clinicians also participated in the majority of the procedures.

To evaluate the clinical consequences of IOAEs for postoperative outcome, the composite end point death/nonfatal moderate to severe complication was determined for patients with and without IOAEs. Because this present study focused only on short-term follow-up, endoleaks identified on control angiograms or on postoperative computed tomography scans were not considered IOAEs or complications.

Results

Patient population

During the 7½ year study period, 113 consecutive elective patients underwent FEVAR or BEVAR. No fenestrated or branched devices were implanted to treat infected or ruptured aneurysms. All patients were deemed at high risk for open repair. Demographic and anatomic data are presented in Table I .

Table I.

Clinical and anatomic data

| CAAA (n = 89) | TAAA (n = 24) | Overall (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data | |||

| Males | 80 (90) | 21 (87) | 101 (89) |

| Age, years | 73 ± 9 | 72 ± 9 | 73 ± 9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (19) | 2 (8) | 19 (17) |

| Tobacco use in last 10 years | 52 (58) | 15 (62) | 67 (59) |

| Hypertension | 62 (70) | 17 (71) | 79 (70) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 46 (52) | 10 (42) | 56 (50) |

| Coronary artery disease | 46 (52) | 7 (29) | 53 (47) |

| Myocardial infarction | 21 (24) | 3 (12) | 25 (22) |

| Congestive heart failure | 22 (25) | 8 (33) | 30 (27) |

| Arrhythmia | 14 (16) | 3 (12) | 17 (15) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19 (21) | 1 (4) | 20 (18) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 17 (19) | 4 (17) | 21 (19) |

| Pulmonary disease | 35 (39) | 9 (37) | 44 (39) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 13 (15) | 4 (17) | 17 (15) |

| Cancer | 14 (16) | 5 (21) | 19 (17) |

| Obesity | 18 (20) | 3 (12) | 21 (19) |

| Anatomic data | |||

| Maximal diameter, mm | 59 ± 10 | 60 ± 10 | 59 ± 10 |

| Type of aneurysm | Short neck/juxtarenal: 63 (71) Pararenal: 20 (22) Suprarenal: 6 (7) |

Type II: 8 (33) Type III: 9 (37) Type IV: 7 (29) |

CAAA, Complex abdominal aortic aneurysm; TAAA, thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm.

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical data as number (%).

Device implantation

Stents implanted in this study population were fenestrated or branched Cook (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind) stents in 96 of 113 (85%), Ventana (Endologix, Irvine, Calif) stents in 9 of 113 (8%) cases, and Anaconda (Vascutek Terumo, Scotland, UK) stents in 8 of 113 (7%) cases. For CAAAs, there were no specific criteria for choosing which stent to use. Choice was made according to the surgeon's preference. For TAAAs, we used the Cook device. Details of stent graft design and number of fenestrations and branches are detailed in Table II . The mean (standard deviation) number of target vessels per patient was 2.8 ± 0.8.

Table II.

Details of stent graft configurations

| Stent graft configuration | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Fenestrated stent grafts | 96 (85) |

| One fenestration | 4 (4) |

| Two fenestrations | 43 (38) |

| Three fenestrations | 36 (32) |

| Four fenestrations | 13 (12) |

| Branched stent grafts | 11 (10) |

| Three branches | 1 (1) |

| Four branches | 10 (9) |

| Stent grafts with fenestrations and branches | 6 (5) |

| Three target vessels | 1 (1) |

| Four target vessels | 5 (4) |

Clinical outcomes and IOAEs

The overall in-hospital mortality was 8.0% (9 of 113 patients). In-hospital mortality rates for the CAAA and TAAA groups were 6.7% (6 of 89) and 12.5% (3 of 24), respectively (Table III ). A total of 28 moderate to severe complications occurred in 21 (18.6%) patients (Table IV ); 17 complications were related to IOAEs, and 11 occurred without any IOAE. In patients with TAAAs, complete paraplegia occurred in three cases (12.5%). Two other patients presented with paraparesis that resolved completely after spinal fluid drainage. In the CAAA group, one patient with a juxtarenal aneurysm who underwent fenestrated stent grafting with three fenestrations presented with hypoesthesia of both limbs that resolved completely after spinal fluid drainage.

Table III.

Details of patients who died during the postoperative course

| Gender | Age, ASA class | Anatomic details and expected technical difficulties | Stent graft | Details of IOAE | Cause of death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who presented with IOAE | ||||||

| Patient 55 | M | 65 years ASA 4 |

Type IV TAAA >50% stenoses of RRA, LRA, and right CIA Shaggy aorta |

4 fenestrations, Cook | RRA and LRA cannulation failure Graft limb occlusion requiring bilateral thrombectomy and iliofemoral bypasses |

Paraplegia, renal failure, pneumonia |

| Patient 74 | M | 78 years ASA 4 |

Type III TAAA >45-degree aortic angulation >50% stenosis of the CT Two accessory renal arteries Severe iliac tortuosity |

4 visceral branches, one additional branch for temporary elective sac perfusion to prevent spinal cord ischemia, Cook | Sizing error: additional branch placed at the level of overlap between two components | Paraplegia, meningoencephalitis after spinal drain placement |

| Patient 80 | F | 71 years ASA 4 |

Juxtarenal AAA >50% stenosis of SMA Narrowed infrarenal aorta (<18 mm) Short occlusion of left CIA Sharp angulation of aortic bifurcation <7.5 mm EIA |

3 fenestrations, Anaconda | Sizing error RRA cannulation failure and difficult cannulation of SMA |

Bowel ischemia due to SMA stent occlusion MOSF despite splenic artery to SMA transposition |

| Patient 95 | M | 82 years ASA 4 |

Pararenal AAA Shaggy aorta |

3 fenestrations, Cook | SMA cannulation failure requiring a bailout chimney stent for the SMA | Cholesterol embolism syndrome, bowel ischemia SMA and CT patent on control computed tomography scan |

| Patients who had no IOAE | ||||||

| Patient 30 | M | 76 years ASA 4 |

Juxtarenal AAA Shaggy aorta Narrowed infrarenal aorta (<18 mm) |

4 fenestrations, Cook | No IOAE | Cholesterol embolism syndrome, bowel ischemia SMA and CT patent on control computed tomography scan |

| Patient 39 | M | 82 years ASA 3 |

Juxtarenal AAA Floating thrombus in the visceral aorta, severe iliac tortuosity |

3 fenestrations, Cook | No IOAE | Cholesterol embolism syndrome, bowel ischemia SMA and CT patent on control computed tomography scan |

| Patient 42 | M | 71 years ASA 4 |

Suprarenal AAA Narrowed infrarenal aorta (<18 mm) |

3 fenestrations, aortouni-iliac device for narrowed aortic bifurcation, Cook | No IOAE but long procedure | Femorofemoral prosthetic graft infection Developed MOSF despite prosthetic graft replacement by a venous graft |

| Patient 49 | M | 76 years ASA 4 |

Juxtarenal AAA Small (<5 mm) LRA |

3 fenestrations, Cook | No IOAE | Pneumonia, SARS |

| Patient 65 | M | 63 years ASA 2 |

Type IV TAA | 4 fenestrations, Cook | No IOAE | Bowel ischemia, unexplained occlusion of SMA and CT stents at day 1 Developed MOSF despite successful SMA stent thrombectomy and colonic and bowel resection |

AAA, Aortic abdominal aneurysm; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CIA, common iliac artery; CT, celiac trunk; EIA, external iliac artery; F, female; IOAE, intraoperative adverse event; LRA, left renal artery; M, male; MOSF, multiorgan system failure; RRA, right renal artery; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; TAAA, thoracoabdominal aneurysm.

Table IV.

Nonfatal early postoperative moderate to severe complications

| Moderate to severe nonfatal complications | N = 28 in 21 patients (18.6%) |

|---|---|

| Systemic | |

| Renal insufficiency | 9 |

| Spinal cord injury | 4 |

| Complete | 1 |

| Transient | 3 |

| Stroke | 1 |

| Colonic ischemia | 1 |

| Deployment/implant-related complications | |

| Access artery thrombosis | 5 |

| Cholesterol embolism syndrome | 2 |

| Arterial perforation | 1 |

| SMA stent occlusion | 1 |

| Access site lymphorrhea | 1 |

| Access site hematoma | 2 |

| Acute limb compartment syndrome | 1 |

| Complications related to IOAE | 17 |

| Complications unrelated to IOAE | 11 |

IOAE, Intraoperative adverse event; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

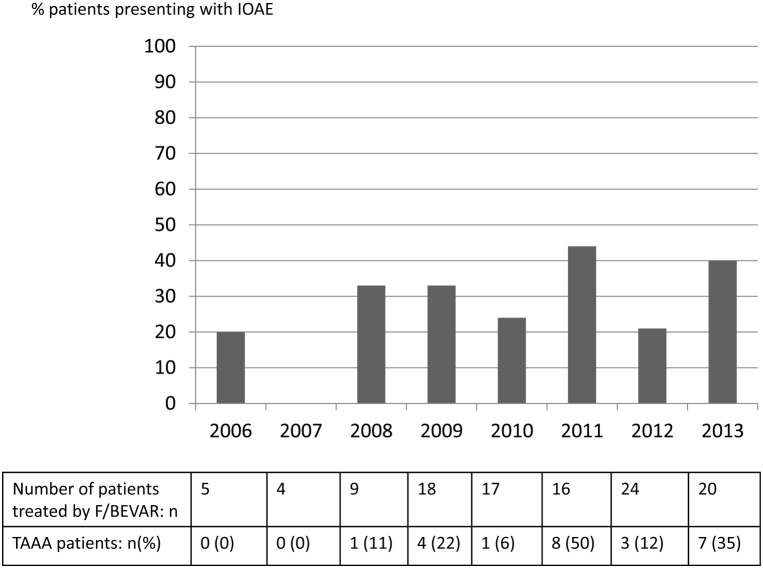

A total of 37 IOAEs were recorded in 34 (30.1%) patients (22 CAAAs and 12 TAAAs). Of 37 IOAEs, 15 (40.5%) resulted in no clinical consequence in 15 patients; 17 (45.9%) were responsible for moderate to severe complications in 16 patients, and five (13.5%) were directly or indirectly responsible for death in four patients. The composite end point death/nonfatal moderate to severe complication occurred more frequently in patients with IOAEs compared with patients without IOAEs (20 of 34 vs 12 of 79; P < .0001, χ 2 test). IOAEs occurred in 22 of 89 (25%) CAAA patients compared with 12 of 24 (50%) TAAA patients (P = .02, χ 2 test). IOAEs occurred in 24 of 96 patients (25%) who underwent a fenestrated stent graft compared with 10 of 17 patients (58.9%) who underwent a branched stent graft (P = .005, χ 2 test). In both those groups, difficulty with target vessel cannulation (type 1 IOAE) was the most frequent (Table V ). The incidence of IOAEs was not significantly different in patients who underwent a Cook fenestrated stent graft compared with patients who underwent an Anaconda or a Ventana fenestrated stent graft. The incidence of IOAE did not change over time (Fig ).

Table V.

Incidence of intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) according to the type of stent graft

| Patients presenting with IOAE | F grafts, | B grafts, | P values,a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cook F (n = 79) | Ventana F (n = 9) | Anaconda F (n = 8) | All F grafts (n = 96) | Cook B (n = 17) | Cook F vs Anaconda F | Cook F vs Ventana F | Anaconda F vs Ventana F | All F grafts vs B Cook | |

| Type 1 IOAE | 10 (12.7) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25) | 14 (14.6) | 8 (47.1) | .3 | .6 | 1 | .002 |

| Type 2 IOAE | 4 (5.1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.2) | 1 (5.9) | 1 | 1 | 1 | .6 |

| Type 3 IOAE | 8 (10.1) | 0 | 0 | 8 (8.3) | 2 (11.8) | 1 | 1 | 1 | .7 |

| Any type of IOAE | 20 (25.3)b | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 24b (25.0) | 10 (58.9)c | 1 | 1 | 1 | .005 |

B, Branched or branched and fenestrated grafts; F, fenestrated; type 1 IOAE, problems with target vessel cannulation; type 2 IOAE, malpositioning of one of the nonfenestrated graft components (bridging stents, bifurcated component, or iliac extensions); type 3 IOAE, difficulty with intraoperative access.

Data are presented as number (%).

Fisher exact test or χ2 test.

Two patients presented with two types of IOAE.

One patient presented with two types of IOAE.

Fig.

Evolution of intraoperative adverse event (IOAE) incidence over time. F/BEVAR, Fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair; TAAA, thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm.

Type 1 IOAEs (problems with target vessel cannulation) occurred in 22 of 113 cases (19.4%), resulting in death (n = 3) or moderate to severe complication (n = 10) in 13 patients (59.1%). They led to target vessel loss in five cases (22.7%). Details of type 1 IOAEs, intraoperative management, and related outcomes are given in Table VI .

Table VI.

Details of type 1 intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) (problems with target vessel cannulation) and clinical consequences

| Type of IOAE | Number of events (n = 22) | Intraoperative treatment | Consequences for target vessel and related outcomes | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA occlusion or dissection | 10 | Thrombolysis: 4 Thrombolysis and thromboaspiration: 2 Thrombolysis and additional stent placement: 2 Additional stent placement: 2 |

Remained patent: 8 | Dialysis: 1 Permanently reduced renal function: 1 Temporarily reduced renal function: 2 No impact on renal function: 4 |

| Target vessel lost: 2 | Permanently reduced renal function: 1 Temporarily reduced renal function: 1 |

|||

| SMA dissection | 1 | Additional sent placement | Remained patent | Asymptomatic |

| RA cannulation failure | 3 | — | Target vessel lost: 3 | Death: 2 Permanent reduced renal function: 1 |

| SMA cannulation failure | 1 | Bailout chimney stent | Remained patent | Death |

| RA rupture | 2 | Additional stent placement: 1 | Remained patent | Asymptomatic |

| Distal coil embolization: 1 | Remained patent | Temporarily reduced renal function: 1 | ||

| Other difficulties during target vessel cannulation | Difficult cannulation of both RAs Mispositioning of a scallop dedicated to SMA Scallop deployed in posterior position Two stents for two right RAs in the same fenestration RRA stented through a scallop dedicated to SMA |

— — — Endovascular occlusion of the nonstented fenestration SMA stented through the same scallop |

Remained patent Partial covering of the SMA Remained patent Remained patent Remained patent |

Long operation, acute compartment syndrome requiring fasciotomies Reintervention for SMA stenting Asymptomatic Asymptomatic Asymptomatic |

RA, Renal artery; RRA, right renal artery; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

Type 2 IOAEs (malpositioning of one of the graft components) occurred in 5 of 113 cases (4.4%), resulting in death or complication in two patients (Table VII ).

Table VII.

Details of type 2 intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) (malpositioning of one of the nonfenestrated graft components) and clinical consequences

| Details of graft component malpositioning | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|

| Sizing error leading to malpositioning and coverage of an additional branch for temporary elective sac perfusion to prevent spinal cord ischemia | Paraplegia, meningoencephalitis after spinal drain placement, death |

| Inadequate positioning of SMA stent, long portion remaining in the aortic lumen | Early occlusion of SMA stent, bowel ischemia Successful endovascular stent removal, placement of another covered stent |

| Right graft limb disconnection requiring placement of an additional graft limb | None |

| Unintentional coverage of the LIIA | None |

| Unintentional coverage of the RIIA | None |

LIIA, Left internal iliac artery; RIIA, right internal iliac artery; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

Type 3 IOAEs (related to access site problems) occurred in 10 of 113 patients (8.8%), leading to early postoperative death in one patient and moderate to severe complications in another six patients (Table VIII ).

Table VIII.

Details of type 3 intraoperative adverse events (IOAEs) (access site problems) and clinical consequences

| Type of access site problem (n = 10) | Intraoperative treatment | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Iliac or graft limb occlusion: 5 | Thrombectomy: 3 | Asymptomatic: 2 Reintervention for acute leg ischemia needing femorofemoral crossover bypass: 1 |

| Thrombectomy and additional stent: 1 | Asymptomatic: 1 | |

| Thrombectomy and iliofemoral bypass: 1 | Reintervention for fasciotomies, death: 1 | |

| Common femoral artery iatrogenic occlusive lesion: 4 | None: unnoticed during the procedure | Reintervention for acute leg ischemia: 4 |

| Iliac injury: 1 | None: unnoticed during the procedure | Flank hematoma, reintervention for coil embolization of the circumflex iliac artery |

Discussion

The utility of fenestrated and branched devices for the treatment of CAAAs and TAAAs has gained widespread acceptance, with several large series confirming satisfactory early and midterm results.5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In a recent systematic review of juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms treated by FEVAR,16 368 FEVAR cases from eight cohort studies were evaluated. The reported 30-day mortality was 1.4%, and the incidence of permanent renal dialysis was 1.4%. Data from national registries and from high-volume centers have provided similar results, with 30-day mortality rates varying from 2% to 4%.13, 14, 17 In expert hands, endovascular repair of TAAA with FEVAR or BEVAR has been associated with encouraging short-term results, with 30-day mortality ranging from 5% to 12% and spinal cord ischemia from 3% to 17%.4, 12, 18, 19, 20

With 30-day mortality rates of 6.7% for juxtarenal patients and 12.5% for TAAA patients, our results do not compare favorably with previously published data. Several reasons might explain this observation. In contrast with pioneering series, in which one physician performed the majority of the cases, two vascular surgeons in our institution performed fenestrated and branched procedures as the first operator, although a highly experienced interventional radiologist (H.K.) was present during almost all procedures. This, combined with the fact that three different types of device were used, might have contributed to IOAEs in some patients. However, more than a simple learning curve of technical skills, one could argue that our results are mainly due to suboptimal patient selection. On review of the mortalities in this series, all patients had challenging aneurysm morphology or significant comorbidity (American Society of Anesthesiologists class 4). Four patients had “shaggy” aortas with floating thrombus, resulting in fatal embolic complications. As FEVAR and BEVAR are being increasingly used and disseminated, the results of our initial experience confirm that they remain complex procedures that need to be centralized in high-volume centers. They also raise the question of whether encouraging results of initial series can be reproduced in the “real world,” knowing these series came from a very few pioneering expert centers and included highly selected patients.

Type 1 IOAEs (problems with target vessel cannulation) were the most frequent in our experience (n = 22). Target vessel occlusions and dissections occurred in 11 cases and were mainly due to target vessel injury or thrombus formation in the long 7F sheaths. Even if most of them could be rescued with additional bailout endovascular maneuvers and without permanent damaging consequences for the patient (Table VI), they are considered avoidable. Thrombus formation in the long 7F sheaths may also have been avoided by more frequent flushing. Cannulation failure was relatively rare (n = 4) but had devastating consequences for the patient, leading directly or indirectly to severe complications or death (Table VI). This was mainly due to sizing errors, malpositioning of the fenestrated component, or difficult anatomy and occurred predominantly at the beginning of our experience.

Type 2 IOAEs (malpositioning of bridging stents, bifurcated component, or iliac extensions) are also considered avoidable technical errors. In our series, they occurred in five cases. In one patient with a type II TAAA, a sac perfusion branch had to be covered as it was inadvertently located at an overlap zone. The patient subsequently died of meningoencephalitis after spinal drain placement for paraplegia, although the use of sac perfusion branches to reduce paraplegia risk remains controversial. With the exception of one endovascular reintervention, all remaining IOAEs relating to graft malpositioning were managed successfully without harm to the patient.

FEVAR and BEVAR procedures are frequently long, require large-diameter introducer sheaths, and are prone to access vessel complications. In this series, intraoperative access site problems (type 3 IOAEs) occurred in 10 patients (8.8%), leading to moderate or severe complications in seven cases. In our current practice, we use a percutaneous approach for most standard EVAR cases. Because of the increased risk of access complications during FEVAR and BEVAR procedures, we still favor surgical cutdown of femoral arteries.

Caution should be taken in interpreting the results of this series as the definition of CAAA is broad, including short neck, juxtarenal, pararenal, and suprarenal aneurysms. Consequently, there was considerable heterogeneity in complexity of aneurysm morphology and difficulty of procedures, which varied from stents with two fenestrations to challenging branched stent grafting for type II TAAAs in high-risk patients. Despite these limits, this study suggests that in routine practice, technical difficulties and IOAEs during FEVAR and BEVAR procedures are not rare, particularly with difficult aneurysm morphology. It is likely that continuous improvements in endovascular and imaging technologies will improve the safety of complex endovascular aortic procedures. Development of lower profile stent grafts and bridging stents, with better visibility and repositionability, will probably play a key role in reducing IOAEs. New tools for improved catheter navigation, such as robotic navigation,21 may also facilitate target vessel cannulation. Although few data exist, fusion of images may be useful to reduce doses of contrast material and radiation.22

Conclusions

In our series, IOAEs during branched and fenestrated stent grafting were frequent, occurring in 25% of patients with CAAAs and 50% of patients with TAAAs. As branched and fenestrated devices are being increasingly used and disseminated in vascular centers, additional studies are needed to determine if the encouraging results from pioneering expert centers can be reproduced in “real-life” practice.

Author contributions

Conception and design: FC, HK

Analysis and interpretation: FC, HK, MG

Data collection: FC, HK, MM, PD, EA, JM, JPB

Writing the article: FC, MG

Critical revision of the article: FC, HK, MG, PD, EA, JM, JPB

Final approval of the article: FC, HK, MM, MG, PD, EA, JM, JPB

Statistical analysis: FC, HK

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: FC, JPB

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Resch T., Sonesson B., Malina M. Incidence and management of complications after branched and fenestrated endografting. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2010;51:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford E.S., Crawford J.L., Safi H.J., Coselli J.S., Hess K.R., Brooks B. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms: preoperative and intraoperative factors determining immediate and long-term results of operations in 605 patients. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:389–404. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson J.L., Adam D.J., Berce M., Hartley D.E. Repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms with fenestrated and branched endovascular stent grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haulon S., D'Elia P., O'Brien N., Sobocinski J., Perrot C., Lerussi G. Endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neill S., Greenberg R.K., Haddad F., Resch T., Sereika J., Katz E. A prospective analysis of fenestrated endovascular grafting: intermediate-term outcomes. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scurr J.R., Brennan J.A., Gilling-Smith G.L., Harris P.L., Vallabhaneni S.R., McWilliams R.G. Fenestrated endovascular repair for juxtarenal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2008;95:326–332. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semmens J.B., Lawrence-Brown M.M., Hartley D.E., Allen Y.B., Green R., Nadkarni S. Outcomes of fenestrated endografts in the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia (1997-2004) J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:320–329. doi: 10.1583/05-1686.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bungay P.M., Burfitt N., Sritharan K., Muir L., Khan S.L., De Nunzio M.C. Initial experience with a new fenestrated stent graft. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1832–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mertens R., Bergoeing M., Marine L., Valdes F., Kramer A., Vergara J. Ventana fenestrated stent-graft system for endovascular repair of juxtarenal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19:173–178. doi: 10.1583/11-3706.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaikof E.L., Blankensteijn J.D., Harris P.L., White G.H., Zarins C.K., Bernhard V.M. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1048–1060. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg R., Eagleton M., Mastracci T. Branched endografts for thoracoabdominal aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(Suppl):S171–S178. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg R.K., Lu Q., Roselli E.E., Svensson L.G., Moon M.C., Hernandez A.V. Contemporary analysis of descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: a comparison of endovascular and open techniques. Circulation. 2008;118:808–817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg R.K., Sternbergh W.C., 3rd, Makaroun M., Ohki T., Chuter T., Bharadwaj P. Intermediate results of a United States multicenter trial of fenestrated endograft repair for juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.05.051. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haulon S., Amiot S., Magnan P.E., Becquemin J.P., Lermusiaux P., Koussa M. An analysis of the French multicentre experience of fenestrated aortic endografts: medium-term outcomes. Ann Surg. 2010;251:357–362. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfda73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verhoeven E.L., Tielliu I.F., Ferreira M., Zipfel B., Adam D.J. Thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm branched repair. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2010;51:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordon I.M., Hinchliffe R.J., Holt P.J., Loftus I.M., Thompson M.M. Modern treatment of juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms with fenestrated endografting and open repair—a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Society for Endovascular Therapy and the Global Collaborators on Advanced Stent-Graft Techniques for Aneurysm Repair (GLOBALSTAR) Registry Early results of fenestrated endovascular repair of juxtarenal aortic aneurysms in the United Kingdom. Circulation. 2012;125:2707–2715. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuter T.A., Rapp J.H., Hiramoto J.S., Schneider D.B., Howell B., Reilly L.M. Endovascular treatment of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roselli E.E., Greenberg R.K., Pfaff K., Francis C., Svensson L.G., Lytle B.W. Endovascular treatment of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1474–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhoeven E.L., Tielliu I.F., Bos W.T., Zeebregts C.J. Present and future of branched stent grafts in thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a single-centre experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riga C.V., Cheshire N.J., Hamady M.S., Bicknell C.D. The role of robotic endovascular catheters in fenestrated stent grafting. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:810–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.101. discussion: 819-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dijkstra M.L., Eagleton M.J., Greenberg R.K., Mastracci T., Hernandez A. Intraoperative C-arm cone-beam computed tomography in fenestrated/branched aortic endografting. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]