Abstract

Two decades ago, the observation of a rapid and sustained antidepressant response after ketamine administration provided an exciting new avenue in the search for more effective therapeutics for the treatment of clinical depression. Research elucidating the mechanism(s) underlying ketamine’s antidepressant properties has led to the development of several hypotheses, including that of disinhibition of excitatory glutamate neurons via blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Although the prominent understanding has been that ketamine’s mode of action is mediated solely via the NMDA receptor, this view has been challenged by reports implicating other glutamate receptors such as AMPA, and other neurotransmitter systems such as serotonin and opioids in the antidepressant response. The recent approval of esketamine (Spravato™) for the treatment of depression has sparked a resurgence of interest for a deeper understanding of the mechanism(s) underlying ketamine’s actions and safe therapeutic use. This review aims to present our current knowledge on both NMDA and non-NMDA mechanisms implicated in ketamine’s response, and addresses the controversy surrounding the antidepressant role and potency of its stereoisomers and metabolites. There is much that remains to be known about our understanding of ketamine’s antidepressant properties; and although the arrival of esketamine has been received with great enthusiasm, it is now more important than ever that its mechanisms of action be fully delineated, and both the short- and long-term neurobiological/functional consequences of its treatment be thoroughly characterized.

1. Introduction:

For the first time in decades, a unique drug has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for antidepressant use. As of 2019, esketamine, a stereoisomer of the popular hallucinogenic party-drug, ketamine [(R,S)-ketamine], has become available in the United States as a nasal spray. The introduction of this drug comes at a crucial point in the history of psychiatry and therapeutic development for the treatment of mental disorders, as major depressive disorder (MDD) has quickly become the top contributor of disability worldwide, surpassing earlier projections by almost fifteen years [1,2]. Depression is a common illness that affects a substantial percentage of the world’s population [1]; and among those afflicted with MDD, there has been an alarming increase in the number of individuals, both adolescents and adults, diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), highlighting the necessity for new therapeutic options [3]. Over the past half century, antidepressant drug development has focused, almost exclusively, on the manipulation of monoamine neurotransmitter systems. Although this approach led to the development of new classes of antidepressants, their mechanisms of action are quite similar, with their therapeutic efficacy remaining unchanged. Considering that these monoamine-based antidepressants have low remission rates (less than 50%), delayed onset of efficacy (weeks-to-months), and high potential for eliciting negative side effects [4], it has remained critical that more effective treatments, with novel mechanisms of action, be developed [5,6]. Thus, the emergence of ketamine/esketamine as a breakthrough therapeutic for the treatment of MDD and TRD has been celebrated, with good reason, by sufferers, clinician practitioners, and the public at large. Although the recent approval of esketamine has been received with great enthusiasm, it is now more important than ever that its various mechanisms of action be fully delineated and both the short- and long-term neurobiological/functional consequences of its treatment be thoroughly characterized.

2. Ketamine’s Symphony Effect:

Depression is a complex heterogeneous disorder likely influenced by both genetic and environmental factors that can manifest itself with great diversity across all afflicted individuals [7]. Various hypotheses have been suggested over the years as to the underlying mechanism of MDD. Most notably and influential has been the monoaminergic theory of depression, which suggests that deficits in monoaminergic transmission underlie depression, since monoamine enhancers improve depressive symptoms [8]. The glutamate theory of depression proposes that an imbalance between glutamatergic and GABAergic activity in the brain leads to toxicity resulting in structural and synaptic remodeling that may underlie depression symptomology [9]; and lastly, the neuroimmune theory, which postulates that dysregulation at the interface of peripheral and central immune system results in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines that can, in turn, promote susceptibility to depression [10,11]. While these theories have informed and guided decades of research, it is unlikely that dysregulation of a single brain mechanism accounts for depression, and more likely that dysregulation of multiple mechanisms act in concert to produce what is uniformly categorized as MDD, and thus identification of the brain hub promoting depression remains elusive. Despite this limitation in our knowledge that has prevented the development of novel therapeutics, ketamine has emerged as a powerful tool to help disentangle the numerous contributing neurobiological factors resulting in depression since its debut as a rapid and robust antidepressant in the 1990s [12]. Notwithstanding the enthusiasm generated, ketamine has a tumultuous history as a psychedelic with abuse potential, and multifarious interactions with several neural systems. Although ketamine has the highest affinity for N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors [13], it is considered a promiscuous drug, possessing varying affinities for, and exerting activity on, a number of other major receptors, including but not limited to, monoaminergic, opioid, adrenergic, and cholinergic receptor systems (see Figure 1) [14]. Aside from central nervous system (CNS) targets, ketamine has been shown to also influence other important physiological systems, including the immune system [15], energy metabolism pathways [16], and the peripheral stress response, which provides negative feedback to the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis [17]. In the brain, ketamine initiates a cascade of cellular events including, but not limited to, triggering second messenger signaling [18], changing the epigenetic state of various stress-related genes [19], and alterations in synaptic plasticity [20]. It is clear that MDD involves dysregulation of several key stress- and reward-related brain regions and, therefore, novel treatments would need to modulate these areas in concert to achieve an antidepressant response [21]. These distinct processes would need to act together with great precision to achieve what we refer to as the “Symphony effect.” Thus, the ultimate success of ketamine as a true antidepressant would likely rest on its ability to act on the various dysregulated biological processes in synchrony.

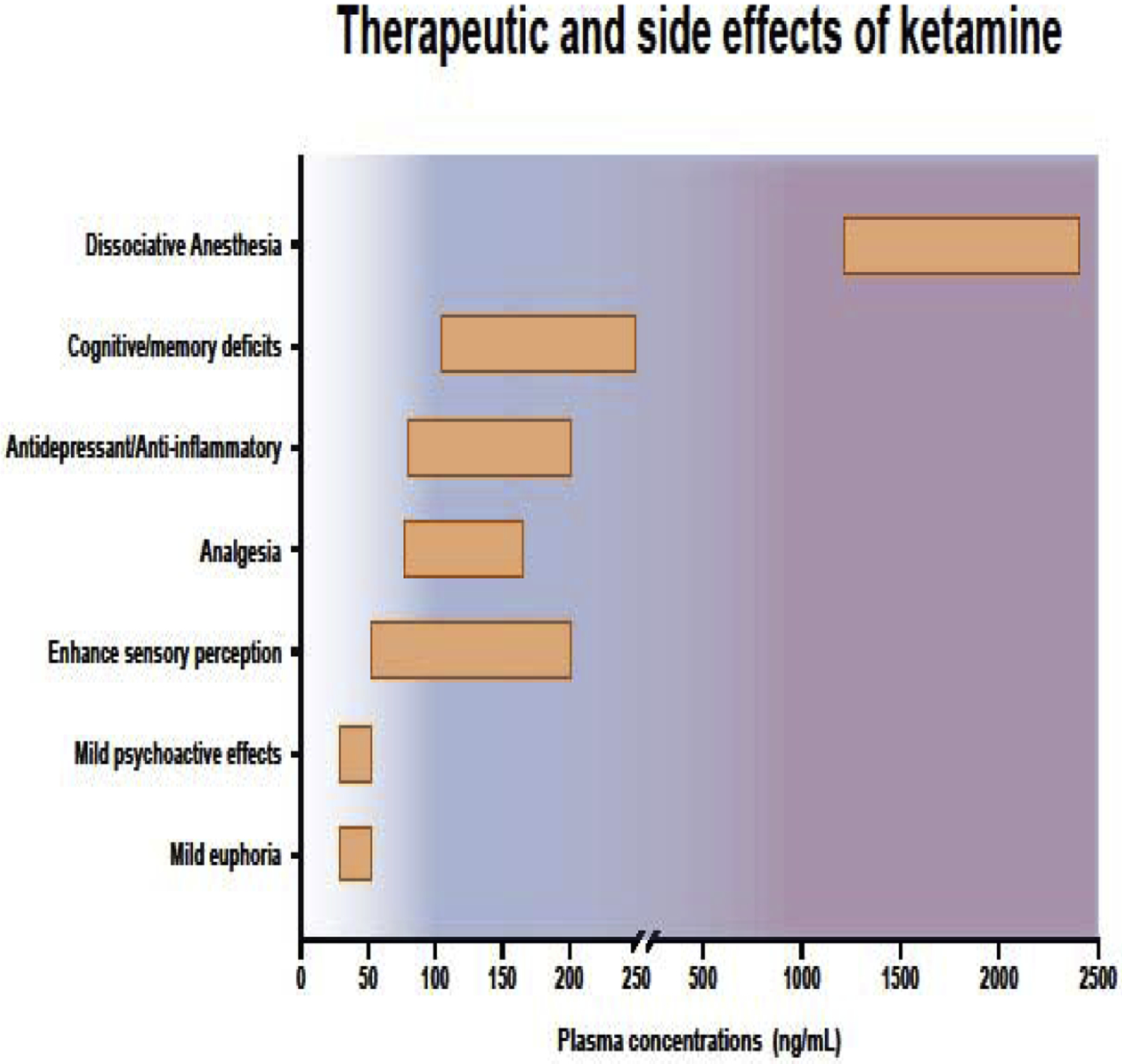

Figure 1: Therapeutic and side effects of ketamine.

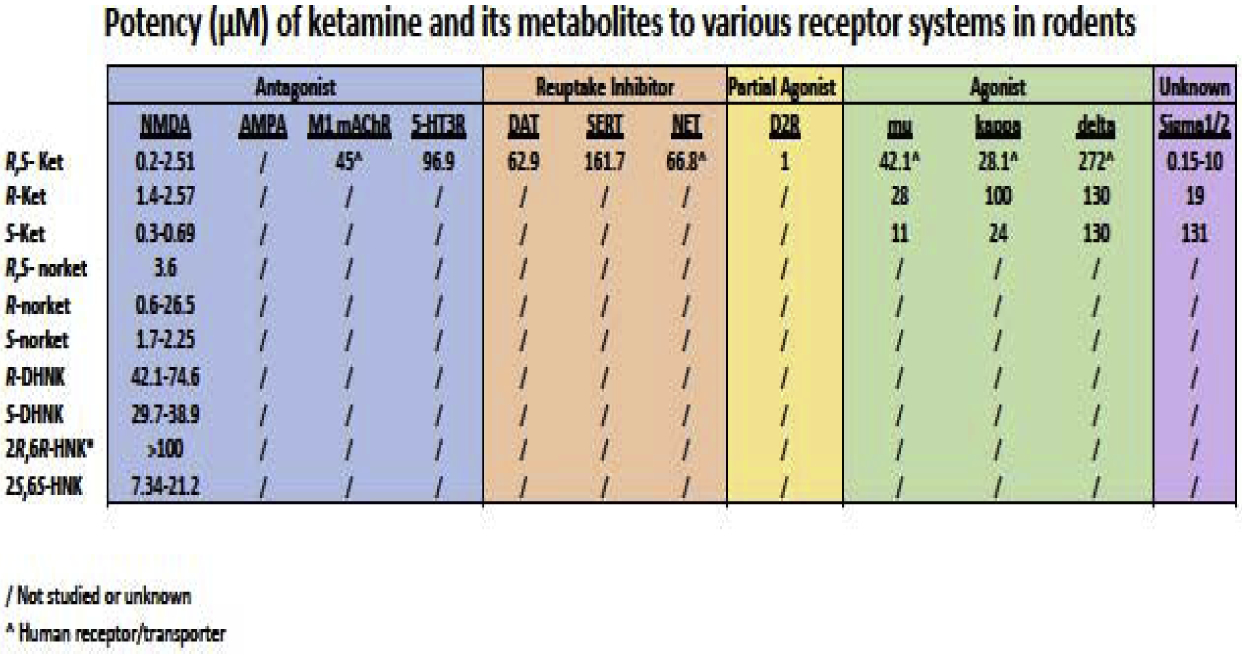

A. These data are taken from the comprehensive review by Panos et al., 2018. The values shown are inhibitor constant (Ki) of ketamine and its metabolites. They are a range of values taken from different brain tissue or culture systems using different ligands. This table illustrates the lack of knowledge about the action and potency of ketamine and its metabolites in many neurotransmitter systems. (/ Not studied or unknown; ^ Human receptor/transporter)

The aim of this review is to provide an update on what is our current knowledge about ketamine and its various molecular mechanisms of action, with a focus on how the NMDA and non-NMDA targets of this drug function, and interact, to induce rapid and sustained antidepressant action. Given the fast-tracking and recent FDA approval of esketamine, we start this review by briefly covering the history of ketamine, the path to its therapeutic status, and then address the recent controversy caused by antidepressant effects observed by its metabolites.

3. Brief history of racemic ketamine as an antidepressant and its pharmacokinetics:

The idea that psychedelic drugs possess therapeutic benefits is not a new concept. In the 1950s, psychedelic drugs, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), were reported to enhance self-awareness and facilitate the recall of emotional memories, providing considerable benefits to psychotherapy [22]. Ketamine became a novel dissociative anesthetic and psychedelic compound derived from its predecessor phencyclidine (PCP) in 1962. By 1964, ketamine had been shown to be a safer, more effective anesthetic agent than PCP [23]. It also proved to be highly versatile, as at varying doses it induces different therapeutic and cognitive side effects (see Figure 2). After being approved by the FDA for use as an anesthetic in 1970, ketamine gained considerable attention in psychiatric research [24–26], and several studies suggested it might possess antidepressant properties [27,28]. Unfortunately, research assessing the antidepressant qualities of ketamine did not resurface until the turn of the century, when a small clinical double-blinded, placebo controlled trial was conducted assessing its antidepressant efficacy in patients with MDD [29]. In this study, rapid antidepressant responses, which progressively emerged over the course of three days, were reported in seven MDD patients. Few years later, Zarate et al. conducted a study to assess ketamine’s efficacy in patients with TRD and also observed rapid antidepressant effects, with 35% of the ketamine-treated patients maintaining their response for at least one week [30]. These findings precipitated a flurry of clinical research with results supporting the hypothesis that ketamine possesses rapid-acting antidepressant properties [31–33]. In addition, there is evidence indicating that ketamine is also efficacious for the treatment of suicidal ideation [34,35].

Figure 2: Potency of ketamine and its metabolites to various receptor systems in rodents.

A. Ketamine is a versatile drug that induces different effects at escalating doses. Figure 2 shows a few examples of ketamine’s beneficial as well as detrimental properties. Ketamine has a wide range of physiological and cognitive effects at subanesthetic doses (plasma concentrations: <1000 ng/mL). At low plasma concentration of 25–50 ng/mL (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.) there is mild euphoria, and little to no psychoactive effects are experienced. Slightly above those concentrations (50–200 ng/mL or 0.1–0.5 mg/kg, i.v.), analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects take place. The antidepressant effects of ketamine also occur during this time and is associated with enhanced sensory perception and memory deficits. At much higher concentrations (1200–2400 ng/mg or 1–2 mg/kg, i.v.), ketamine induces dissociative anesthesia.

The versatility of ketamine as a therapeutic may come from its unique structure and subsequent function of its active metabolites. Unlike PCP, racemic ketamine is a chiral compound, consisting of a mixture of equal amounts of the R- and S- stereoisomers. These mirror compounds have proven to be useful anesthetics/analgesics, with S-ketamine generally being more potent than R,S-ketamine and R-ketamine [36,37]. Although ketamine binds poorly to plasma proteins, its liposolubility allows it to be rapidly and globally distributed regardless of route of administration [38,39]. Ketamine is rapidly (within 2–3 minutes) metabolized, with each of its S- and R- enantiomers being metabolized primarily into R,S-norketamine (the major active metabolite), hydroxyketamine, dehydro-norketamine, and a series of six diastereomeric hydroxynorketamines (6-HNK) by the cytochrome P450 liver enzymes CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 [40–42]. CYP3A4 demethylates S-ketamine more rapidly than R-ketamine, thus conferring a greater rate of clearance for S-ketamine, while CYP2B6 demethylates both stereoisomers with roughly equal efficiency [43,44]. Of the six derived HNK metabolites, four 2R,6R;2S,6S-HNK have been predominantly detected in the plasma of MDD patients after a single intravenous (i.v.) infusion of ketamine [45,46], and their formation has been associated with increased hydroxylation of S-ketamine, relative to R-ketamine [46]. It is now being suggested that these HNKs may be responsible for the antidepressant effects of ketamine [47], thus making the different properties of these metabolites valuable pharmaceutical tools for the treatment of depression, and this will be further discussed in the Stereoisomers and Metabolites section below (Section 5).

4. Involvement of the glutamatergic system in ketamine’s antidepressant response:

As the main excitatory neurotransmitter of the CNS, glutamate is found in more than 80% of neurons, and in higher concentrations than the monoamines [48]. The glutamatergic system is regulated via the tripartite synapse, which includes pre- and postsynaptic neurons along with glial cells, and it is modulated by both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors [49]. There are three types of ionotropic glutamatergic receptors, including NMDA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPAR), and kainate receptors. While ionotropic receptors induce rapid cellular changes in response to stimuli, glutamate is thought to be homeostatically regulated by three classes of metabotropic receptors (mGluR). Postmortem tissue of suicide victims with MDD showed evidence of dysregulated glutamatergic neurotransmission as seen through reduction in binding of high affinity ligands to NMDARs [50]. Similar dysregulation is seen in rodent brains that undergo chronic stress paradigms [51] and, interestingly, in these models, NMDA activity is normalized by chronic treatment with classic antidepressants [52,53]. When the NMDAR antagonist ketamine was shown to elicit a rapid (within hours), robust, and relatively long-lasting antidepressant response in clinical trials, with findings paralleled by preclinical studies [29,30,54,55], the glutamatergic system was solidified as a potential therapeutic target for the development of increasingly effective and fast-acting antidepressants. The interaction between ketamine and the glutamatergic system is complex and dynamic, and in the following sections, we will dissect this interaction(s) and its relationship to antidepressant activity.

4.1. NMDA receptors and subunit composition:

NMDA receptors are present on almost every cell within the CNS [56]. The endogenous ligands for NMDARs come from various sources, including synaptic glutamate spillover, glial release of glutamate, glycine, and D-serine [57]. Thus, the prevailing question is, how does antagonism of the NMDAR produce antidepressant effects? To answer this question, the structure and kinetics of NMDARs must first be understood. NMDARs are unique in that they have high permeability to calcium, and unusually slow activation/deactivation kinetics, with their functional properties being dictated by their specific subunit composition [58]. NMDARs are heterotetrameric complexes composed of 3 subunit varieties: GluN1, GluN2A-D, and GluN3A-B [59]. NMDARs most typically include 2 GluN1 subunits and either 2- GluN2 or GluN3 subunits [60]. The GluN2A subtype is ubiquitously expressed synaptically, whereas the GluN2B subtype is expressed extrasynaptically in many limbic regions [61–63]. There are 8 variants of GluN1 which occur through alternative splicing of the GRIN1 gene; however, all variants produce the binding site for glycine and D-serine [64]. GluN2 subunits are products of different genes and hold the glutamate binding site [65]. Therefore, a receptor composed of GluN1 and GluN2 subunits requires binding of both glutamate and glycine in order to elicit activation [66]. Alternatively, the combination of GluN1 and N3A-B subunits produces a receptor that activates upon binding of glycine without requiring glutamate or NMDA [67]. It is thus expected that the different permutations of these glutamate subunits would have varying affinities for similar ligands. Glutamatergic signaling is also regulated via extrasynaptic NMDARs (e.g. distal from the postsynaptic density) consisting primarily of GluN2B-enriched heterodimers, therefore possessing a higher affinity for glutamate [52]. These specialized receptors play an important role in glutamate homeostasis and are more likely to contribute to excitotoxity [68]. Another important feature of NMDAR activity is that most receptor complexes contain a voltage-gated channel blocked by Mg2+, and activation of these receptors is contingent upon postsynaptic depolarization to release the Mg2+ block [69]. Recently, identification of a triheteromeric NMDARs consisting of one GluN1, two GluN2B, and one GluN3A subunits were described [70]. These receptors are completely insensitive to Mg2+, making them much easier to activate than their Mg2+-dependent counterparts [70].

Not surprisingly, there are many subunit combinations that provide the CNS with a repertoire of NMDAR motifs, each with unique properties. Accordingly, the specific mechanism of action of a given antagonist will dictate which types of NMDARs are targeted and to what extent. Upon activation, NMDARs experience a Ca2+ influx that initiates intracellular signaling cascades, and overactivation can result in cell death (excitotoxicity). However, study of receptor composition is difficult because of the vastly similar structure of the NMDA subunits. Without highly selective markers to label the different subunits, it is currently impossible to localize where these subunits are present the most and when they are preferentially activated.

4.2. Types of NMDAR antagonism:

There are three classes of NMDAR antagonists: competitive antagonists, uncompetitive channel blockers, and non-competitive allosteric inhibitors [71]. Although ultimately resulting in a similar outcome, each antagonist class has a distinct mechanism of action. Competitive NMDAR antagonists act by occupying the glycine or glutamate-binding site located on either the GluN1 or GluN2 subunit, respectively [72]. This class of antagonist prevents endogenous ligand binding, thereby preventing activation of the receptor. Competitive and uncompetitive antagonists tend to be poorly selective for a specific GluN1/GluN2 subunit, whereas noncompetitive allosteric inhibitors display much higher selectivity. Uncompetitive channel blockers act by occluding the NMDAR ion channel pore. Uncompetitive channel blockers of NMDAR are typically positively charged and require depolarization, such that the Mg2+ block is removed and the binding site exposed [72]. Once bound, these channel blockers can prevent the flow of ions in/out of the channel thus producing inhibition. It is important to note that when channel blockers are in the pore, glutamate may still bound to the NMDAR potentially resulting in Ca2+-independent intracellular signaling; though the significance of this phenomena is not fully understood [73]. Finally, non-competitive allosteric modulators inhibit activity of NMDARs by acting at the N-terminal or “agonist-binding” domains of the GluN1/GluN2 subunits to reduce the activity of the receptor by decreased binding of endogenous ligands. These modulators are deemed non-competitive because they do not compete with endogenous ligands for binding, but they still affect receptor activity.

Compounds from all three classes of NMDAR antagonists have been investigated for antidepressant efficacy. Perhaps most promising so far has been the class of uncompetitive channel blockers such as ketamine, dizocilpine (MK-801), and memantine [74]. Although these drugs have demonstrated rapid antidepressant responses in animal models [54,75–77], only ketamine has shown efficacy in humans [29,30,32,78]. Trials testing the antidepressant potential of memantine in humans have failed to show clinical efficacy [79], and MK-801 has not been investigated for the treatment of depression in humans due to fears of toxicity and the potential for adverse side effects [80]. As stated, ketamine possesses a unique ability to produce rapid (within hours) and long-lasting (up to 1 week) antidepressant effects in both preclinical testing and clinical trials, even when compared to other NMDAR antagonists with similar mechanisms of action. For example, the non-selective and non-competitive NMDA antagonist Lanicemine (AZD6765) exhibited antidepressant efficacy over placebo in treatment-resistant patients, but the effect was not quite as robust or sustained as the one observed with ketamine [81]. Additionally, the competitive antagonists 2-amino-7-phonophetanoic acid (AP7) and 3-(2-Carboxypiperazin-4-yl) propyl-1-phosphonic acid (3-CPP) have exhibited rapid antidepressant responses in animal models, but the duration of the effect is much shorter than that observed with ketamine [54,82]. Similar to MK801, AP7 and 3-CPP have not been used in human trials due to fears of adverse side effects and potential toxicity [83,84]. Synthetic derivatives of ketamine such as methoxetamine, N-ethylnorketamine hydrochloride (N-ENK), and 2- and 4-methoxy-N-ethylketamine hydrochloride (2- or 4-ENK) have strong affinities for the NMDAR and demonstrates antidepressant-like effects in naive mice [85]. Although many of these antagonists have shown promise, they often induce conditioned place preference (CPP), a behavioral paradigm widely used to assess the rewarding properties of drugs of abuse [86,87], thus limiting their potential for use in humans due to increased abuse liability [88].

NMDAR antagonists that are selective for only the GluN2 subunit have also shown some promise in clinical trials. For example, the allosteric modulator Traxoprodil (CP-101,606), which has high selectivity for the GluN1/GluN2B subunit, has been shown to produce antidepressant responses in humans [89]; however, corroborating evidence in animals models is lacking and therefore the safety of its prolonged use is unknown. Additionally, patients did not report relief of symptoms until 2 days post-treatment, indicating that the therapeutic onset of Traxoprodil is not as rapid as that of ketamine [89]. The development of this compound has since been discontinued due to potential cardiac interactions [90]. The lack of a relatively rapid antidepressant response compared to ketamine is a common finding with GluN2B selective inhibitors, as the typical onset of antidepressant effects is 5–8 days.

4.3. Ketamine vs. other NMDAR antagonists:

It has become increasingly apparent that NMDAR modulation is important in mood-related homeostasis, however, the precise mechanism(s) by which ketamine achieves rapid and sustained antidepressant responding is still elusive. To this end, teasing apart the specific mechanistic differences between these compounds is of critical importance. To this end, we must first consider the physiological context in which these agents are able to achieve their actions. For example, since competitive antagonists must compete with endogenous ligands for receptor occupancy [91], they are more likely to bind to NMDARs when in a resting state and subsequently become dislodged under active conditions of high glutamate/glycine. In comparison, uncompetitive channel blocker antagonists such as ketamine are unable to bind to most NMDARs at rest and must rely on previous depolarization to remove the Mg2+ block. This feature becomes increasingly important when considering the physiology within the brain of an individual with MDD where, presumably, glutamate levels are elevated [92–94]. Therefore, the use of competitive antagonists such as AP7 or 3-CPP, for example, may not be as effective in the presence of excess glutamate simply because they cannot outcompete the endogenous ligand. Instead, it is possible that under disease states these antagonists preferentially act in areas of the brain that are not high in glutamate, potentially neglecting the pathological sites that are most vulnerable to excitotoxicity [95].

Among the uncompetitive antagonists, the differences in antidepressant efficacy can most fully be explained by the pharmacodynamic properties of each compound. These agents differ mainly in their affinity for the NMDAR and the physical location in which they occupy the receptor pore. In contrast to ketamine and MK-801, memantine has a lower affinity for the NMDAR [96], and also exhibits much faster ligand binding/unbinding kinetics [91,96]. The low affinity for NMDARs along with differences in binding kinetics may explain why memantine has failed to elicit antidepressant responses in the clinical trial previously mentioned by Zarate et al. [79,97]. Interestingly, the position of memantine’s binding site in the ion channel results in a “partial trapping” in the presence of Mg2+, causing an incomplete closure of the ion channel [91]. In comparison, MK-801 and ketamine bind deeper within the NMDAR’s ion channel and can become trapped upon closure of the channel [97]. Ketamine’s degree of trapping block is around 86%, while MK-801’s is 100%, and approximately 50–70% trapping for memantine [61]. This allows MK-801 and ketamine to remain in the channel and re-antagonize the receptor upon subsequent depolarization. Although both MK-801 and ketamine display high-affinity for NMDARs and show relatively similar trapping block properties, MK-801 has extremely slow unblocking kinetics compared to ketamine [91]. Behaviorally, both drugs produce rapid antidepressant effects, but ketamine exhibits a longer-lasting response than MK-801 (1-week vs. 3hr, respectively) [54,98]. Although MK-801 may initially produce rapid therapeutic effects, its prolonged channel blockade reduces the receptor’s ability to return to basal levels. Slower unbinding kinetics combined with the ability to be trapped within the ion channel would then leave the receptor chronically inhibited. Within this framework, if hyperexcitability of the NMDAR is involved in the pathophysiology of depression, MK-801 produces rapid effects by blocking excess glutamate release but would then occupy the channel long enough to interfere with normal synaptic transmission. In contrast, ketamine’s open-channel blocking/unblocking kinetics and duration of binding appears ideally suited to induce the modifications necessary for antidepressant efficacy without interfering with normal synaptic transmission [99,100].

4.4. Allosteric modulators of NMDARs:

Ligands, protons (H+), and ions (Mg2+ and Zn+) that bind to the allosteric sites of the GluN2B subunit or at the glycine site can noncompetitively inhibit the NMDAR. Precisely where protons are interacting with the receptor is unknown, but due to the pH sensitive nature of the GluN2A/2B under physiological conditions, nearly half of the receptors may be tonically inhibited by these protons [101]. Zn+ binds to an area of the N-terminus domain and changes conformation of the subunit resulting in its closure. Zn+ deficiency induces depression-like symptoms [102], while Zn+ supplement show antidepressant-like effects in preclinical studies [103]. Other drugs that act on areas that overlap with the Zn+ binding domain on the N-terminus might also have potential for antidepressant activity [104]. Traxoprodil and Rislenemdaz (MK-0657), both allosteric site modulators, exhibited delayed and transient antidepressant efficacy. D-cycloserine binds to the glycine coagonist site of the NMDAR, acting as a partial agonist. In addition, D-cycloserine also acts as a NMDA antagonist, and displays antidepressant efficacy in patients but only when baseline serum levels of glycine are above 300 μM [105]. Glycine antagonists that inhibit the NMDAR such as 7-chlorokynurenic acid have also shown antidepressant efficacy in the learned helplessness paradigm. Interestingly, these drugs did not show sensory dissociation or abuse liability like ketamine [106]. Other glycine site ligands such as rapastinel (GLYX-13) had shown significant antidepressant efficacy without dissociative effects in Phase 2 clinical trials, though Phase 3 trials failed to meet primary endpoints [107,108]. More potent analogs of GLYX-13 are undergoing clinical trials and appear to be well tolerated by patients (Clinical Trial: NCT02366364) [90]. Thus, it is conceivable that allosteric inhibitors may prove to be useful in some pathological disorders due to their high subunit selectivity and non-competitive nature but have yet to achieve the level of antidepressant efficacy observed with uncompetitive antagonists such as ketamine.

4.5. Glutamatergic/GABAergic transmission:

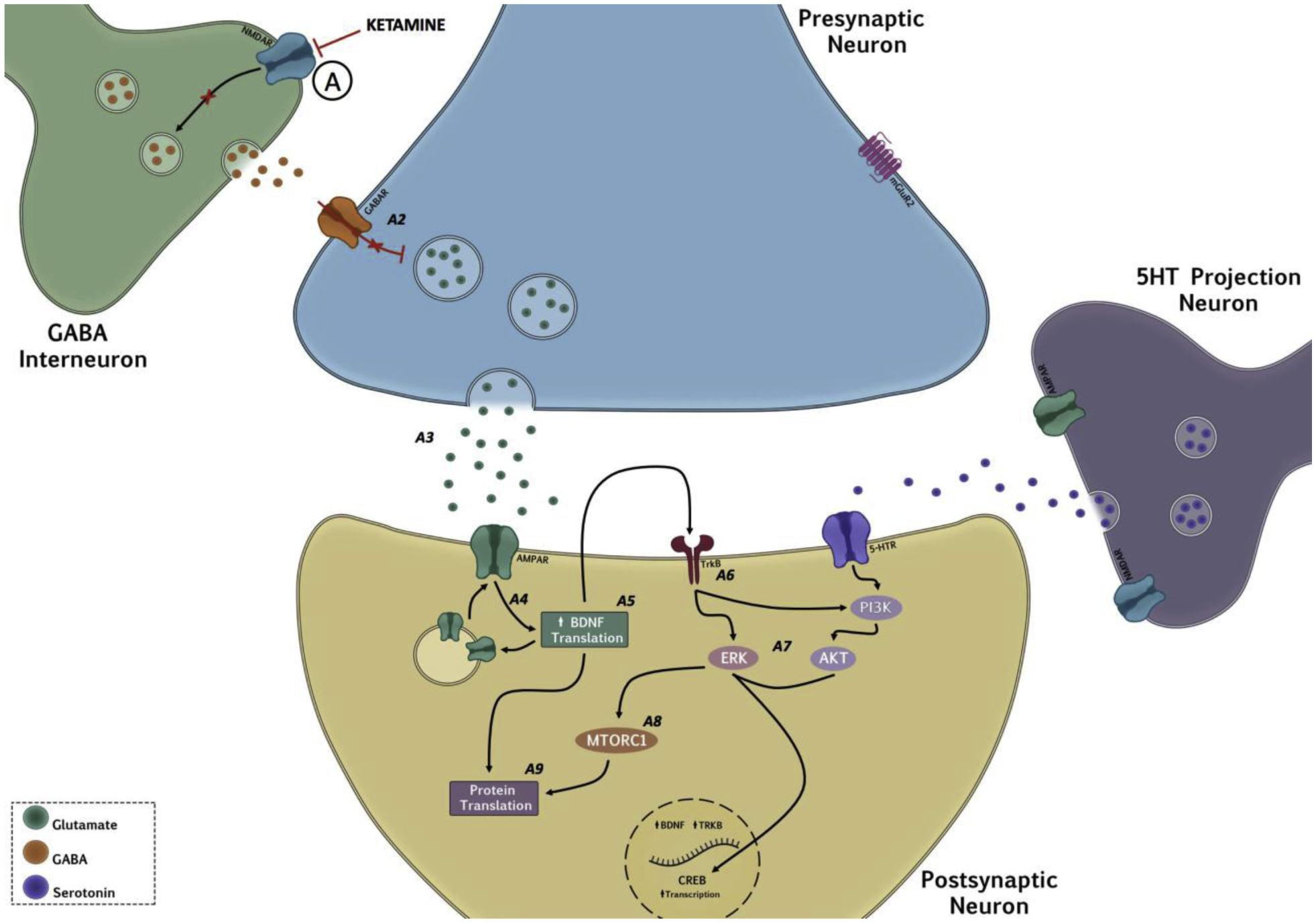

A well-orchestrated balance between glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission is critical for normal brain function. Several lines of evidence suggest that deficits in GABA function is also associated with MDD and other affective disorders [109,110]. Despite of what may be thought about the canonical effect of an antagonist, acute administration of low-dose ketamine results in a transient (1hr) increase in glutamate release within the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [111,111,112]. How can this be achieved? The disinhibition hypothesis provides a framework stating that this increase in glutamate release is due to preferential antagonism of the NMDAR on tonically active GABAergic interneurons. Antagonizing these receptors subsequently removes the inhibition (i.e., disinhibition) on pyramidal glutamatergic neurons, allowing for glutamate release. This increase in glutamate activates the AMPARs of nearby neurons that subsequently provide enough depolarization to expel the Mg2+ block, allowing ketamine to bind and antagonize other NMDARs. One of the many mysteries surrounding ketamine’s mode(s) of action is the mechanism behind its selective inhibition of GABAergic interneurons within the PFC, despite its generally poor subunit selectivity. The discovery of functional triheteromeric NMDARs within the cortex provides a useful framework of action [111]. Therefore, assuming that these receptors are located on GABAergic interneurons within the PFC, ketamine would preferentially antagonize these receptors given that Mg2+ does not actively block their ion channel. By favoring NMDARs located on GABAergic interneurons, disinhibition of glutamate release would precede inhibition of other NMDAR bearing neurons and, depending on the type of neuron being targeted, this antagonism would provide a second level of action that does not necessarily involve the release of glutamate. Despite this being the most commonly accepted hypothesis for the antidepressant mechanism of ketamine, there is a paucity of direct evidence linking specificity for low-dose ketamine with NMDAR on GABAergic interneurons. Recent evidence has emerged, in support of this hypothesis, demonstrating ketamine’s antidepressant effects could be blocked by knocking down GluN2B-containing NMDAR in GABAergic interneurons [113]. However, a different study has shown that ketamine can retain its antidepressant efficacy in systems with a NMDAR knockout in a subset of GABAergic interneurons [114]. Though limited in its scope, this finding complicates the framework provided by the disinhibition hypothesis, and more studies will need to be done to replicate these findings, which will be crucial in understanding the mechanism underlying ketamine’s antidepressant actions.

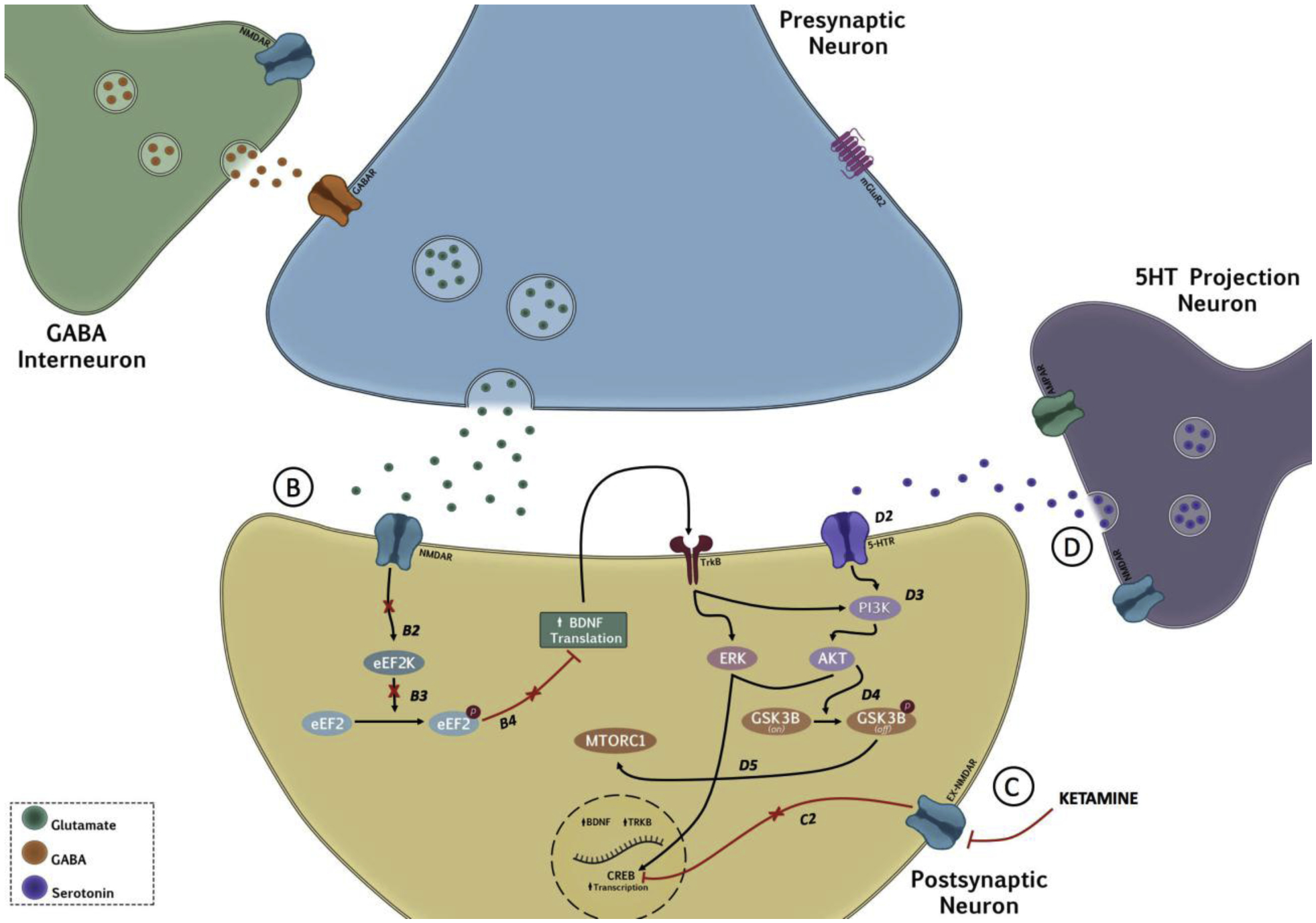

Another prevailing hypothesis based on preclinical studies is that ketamine directly antagonizes NMDARs on excitatory neurons that happen to be tonically activated by ambient glutamate or spontaneous glutamate release. In this case, ketamine would block spontaneous vesicular glutamate release and the system would then compensate by increasing synaptic drive via increased protein translation and formation of new synapses (synaptogenesis) [115]. Some studies have reported that GluN2B-containing NMDARs are highly sensitive to ambient glutamate release [116], lending support to the hypothesis that low-dose ketamine binds to these tonically active NMDARs on excitatory neurons, and that as the concentration of ketamine increases, the gradual suppression of NMDA tone would lead to dissociation and anesthesia. In the same vein, blocking GluN2B-containing NMDAR typically found extrasynaptically can block excitotoxicity thought to be associated with MDD and promote synaptic glutamate transmission [62]. More studies are needed to elucidate the localization of GluN2A/B-containing receptors and where low-dose ketamine is preferentially binding to. Given that NMDA receptors are present on glial cells such as astrocytes [117] and participate in regulating neurotransmission, the antidepressant effects of ketamine are likely associated with the intracellular signaling and synaptic plasticity changes in both neurons and glia.

4.6. Role of AMPARs in ketamine’s antidepressant activity:

Although it is clear that NMDAR-mediated mechanisms play an important role in ketamine’s antidepressant action, there is also evidence indicating a role for AMPA receptors. Consisting of four main subunits (GluA1–4), AMPARs do not follow the same stoichiometric rules as NMDARs, are therefore more diverse in subunit composition, and endowed with a wide range of functions [118]. AMPARs are not only necessary for proper functioning of NMDARs, but their activation and phosphorylation can have several direct effects on synaptic transmission (i.e., long-term potentiation) and intracellular signaling, certainly making them valuable therapeutic targets [119,120]. Indeed, several studies have shown that blockade of AMPARs prevents the antidepressant effects of ketamine without affecting the efficacy of tricyclics such as imipramine [98,121]. These findings therefore suggest that simple blockade of NMDARs is not sufficient for producing antidepressant effects and that other mechanisms must be at play.

Preclinical investigations have demonstrated that treatment with an AMPAR potentiator alone is capable of producing rapid antidepressant effects [121]. Interestingly, AMPAR activation results in downstream events that cause the release of norepinephrine (NE) [122], serotonin (5-HT), and dopamine (DA) [123], all of which have been linked to the therapeutic action of traditional antidepressants. Supporting this framework, knockout mice lacking AMPAR subunit GluA1, show decreases in 5-HT and NE, and increases in glutamate levels in the hippocampus, which would theoretically mirror the neurotransmitter deficits in the brain of the depressed patients [124]. Additionally, studies have shown that ketamine exposure increases the ratio of AMPA/NMDA density in the whole hippocampus of rodents, indicating an increase in synaptic scaling and a decrease in silent synapses [125]. There is, however, some dispute about ketamine’s effects on AMPAR expression and phosphorylation levels. Some groups have shown no change in GluA1 expression, and a reduction in phosphorylation (i.e., preventing desensitization), [98], while others show that ketamine treatment increases levels of AMPARs at 24hr post injection in whole hippocampus synaptoneurosomes [47]. These differences are likely due to the time-course of action of ketamine and its metabolites, and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms in involved in the insertion of AMPARs into the plasma membrane in more specific regions in the hippocampal formation to tease apart the pertinent pathways that may be involved [126].

Allosteric modulators of the AMPAR that prevent desensitization of the receptor have also shown antidepressant-like effects, though not as rapid as the NMDA antagonists, but faster than classical selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine [98,127]. AMPAkines, which act as AMPA positive allosteric modulators (PAM), have also exhibited antidepressant efficacy when tested in animal models of depression-like behavior as measured by the forced swim test (FST), an index of behavioral despair and learned helplessness, which is indicative of a depressive-like phenotype [121,128]. PAMs have been found safe to use in clinical trials. The AMPAkine Org26576 showed modest alleviation of depression symptoms, although healthy controls reported experiencing negative side effects such as dizziness, nausea and intoxication while being exposed to just half the dose used on individuals with MDD [129]. Interventions that effectively restore glutamatergic transmission by promoting changes in AMPAR kinetics, composition, and/or density could potentially provide relief from depression-related discomfort. Taken together, these data suggest that dysfunction of AMPARs may be highly involved in depression, making them a viable therapeutic target as well.

4.7. Role of mGluR in antidepressant responses:

Another key modulator of the glutamatergic system is the presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) [130]. These g-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) are separated into three classes based on their structure and function. Class 1 receptors increase NMDAR activity, thus potentially contributing to excitotoxicity, whereas Class 2 and 3 tend to decrease NMDA activity. Of the Class 1 mGluR’s, mGluR5, located extra-synaptically at post-dendritic synapses, has shown the most potential as a target for antidepressant action [131]. Preclinical studies show that mGluR5 antagonists have both anxiolytic and antidepressant-like properties; however, there are few indicators that this treatment would be as effective in alleviating depression-related deficits in humans [129]. Class 2 receptors, which include the presynaptic mGluR2 and mGluR3, are found in high density within brain regions implicated in cognitive-related behaviors and emotional response [132]. mGluR2, which acts as an autoreceptor, tightly regulates glutamate at the synapse, and mGluR3, mostly found on glial cells, can also indirectly modulate synaptic glutamate. Because both of these receptors are coupled to Gi subunits, and thereby inhibit adenylyl cyclase, Class 2 mGluR’s are crucial inhibitors of glutamatergic overactivity, and therefore play an important role in the regulation of stress responding [132]. Altered expression of mGlur2/3 receptors is seen in postmortem brain tissue of patients with MDD, and in that of rodents that undergo chronic stress paradigms, highlighting the importance of mGluR’s ability to modulate appropriate stress adaptations [133]. Furthermore, administration of mGluR2/3 antagonists such as MGS0039 have shown to attenuate anhedonia after chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) by reversing the CSDS-induced deficits in sucrose preference [134]. Interestingly, mGlur2/3 antagonism confers antidepressant-like effects in models of stress without increasing locomotor activity, impairing cognition, or posing heightened abuse potential, which are some of the major concerns surrounding treatment with ketamine and its analogs [135,136]. Currently, no studies have investigated the efficacy of direct mGluR2/3 antagonism in humans, however, there are two ongoing clinical studies investigating the utility of positive (NCT00985933) and negative (NCT01546051) allosteric modulators as possible therapeutic agents. To this end, only AZD8529, a PAM of mGluR2, has been identified as safe for use in humans [137]. Use of mGluR2/3 agonists have shown that the metabotropic receptors are needed for the glutamate surge seen in the medial PFC after systemic ketamine administration [111]. Conversely, the use of mGluR2/3 antagonists such as LY341495 can enhance the antidepressant-like effect of ketamine in rats [138]. In support of these findings, more recent preclinical studies have reported that metabolites of ketamine and mGluR2/3 antagonists may share a similar antidepressant mechanism. Administration of sub-effective doses of mGluR2/3 antagonists, in combination with the metabolite 2R,6R-HNK induced synergistic antidepressant responses in mice, though direct causation was not shown [139]. The possibility of a convergent mechanism that utilizes the metabotropic glutamatergic system to regulate mood and behavior opens up a new avenue for potential therapeutics, though more work is needed to understand how ketamine and its metabolites are indirectly influencing the system.

5. Stereoisomers and metabolites of ketamine:

Though commercially available ketamine is typically a racemic mixture (R,S-), each of its stereoisomers possesses varying pharmacokinetic properties and affinities for receptors, thus potentially making them distinct pharmaceutical tools for antidepressant action. Interestingly, ketamine’s antidepressant activity persists after both the parent compound and metabolites are no longer detectable in the brain [140]. These compounds along with their associated metabolites possess differing affinities for various receptor systems, and subsequently exert disparate behavioral effects. As stated, (R,S)-ketamine itself induces dissociative side effects and has abuse potential; however, several groups have shown that the isolated molecules (i.e., R- and S-ketamine) may not have the same attributes, and this is an area of high research activity. Below we cover what is currently known about these enantiomers and their metabolites’ mechanisms of action. However, it must be noted that our current understanding does not present a complete picture, and more studies are needed to tease apart their specific sites of action along with their behavioral effects (see Figure 2).

Esketamine or S-ketamine is being marketed as Spravato for treatment of intractable MDD. S-ketamine rapidly gained traction as several clinical off-label studies with i.v. racemic ketamine demonstrated its efficacy as a rapid acting antidepressant. It is conceivable that S-ketamine was fast-tracked due to the fact that it has a four- to five- fold greater affinity for the NMDA receptor (NMDAR) than R-ketamine and therefore thought to possesses greater antidepressant efficacy [141]. S-ketamine is also easier to demethylate than R-ketamine, thus conferring a greater rate of clearance [43]. Given its higher affinity to NMDARs, S-ketamine induces superior analgesic effects, but it also produces heightened hypnotic and sensory distortion [36]. Interestingly, although S-ketamine was recently approved for antidepressant use, R-ketamine has demonstrated greater antidepressant efficacy in animal models [142], and shown fewer dissociative and hallucinatory side effects in healthy humans [143]. Indeed, Hashimoto and colleagues have argued that R-ketamine exhibits longer lasting antidepressant-like effects at lower doses than S-ketamine, potentially rendering it a more potent and safer therapeutic than S-ketamine [74]. Furthermore, the effects of S-ketamine have been muddled, as it did not show antidepressant efficacy in the learned helplessness model [142]. Given this, it is surprising that as of today, there are no registered clinical trials that have been conducted, or currently ongoing, using R-ketamine in the United States or the European Union.

Further complicating matters, Zanos and colleagues have proposed that metabolism of R-ketamine to 2R,6R-HNK is responsible for increasing the potency of R-ketamine’s antidepressant-like properties. This result is interesting due to 2R,6R-HNK’s extremely low affinity for NMDARs (Ki >100μM) [144], suggesting that this metabolite may also elicit an antidepressant-like effect by acting via a different (i.e., non NMDA) target from ketamine or R-ketamine. Interestingly, Zanos et al. showed that 2R,6R-HNK increased acute glutamatergic signaling and exhibited antidepressant activity similarly to racemic ketamine. These effects were suggested to be due to an increase in AMPAR activation, as demonstrated in hippocampal CA1 slices, and further confirmed in the same study by showing that the antidepressant-like effects of 2R,6R-HNK were blocked by pretreatment with the AMPA antagonist NBQX. Surprisingly, 2R,6R-HNK exhibited antidepressant-like efficacy at 24hrs, well past its projected bioavailability of 2hrs. This effect was proposed to be mediated by 2R,6R-HNK-induced upregulation of AMPARs (GluA1/A2) in hippocampal synapses, but not in the PFC. Because of ketamine’s abuse potential, the authors also tested this compound in the self-administration paradigm and determined that 2R,6R-HNK possessed a lower rate of self-administration, thus indicating a lower abuse/addiction liability as compared to ketamine [47]. Since this publication, there have been several other studies demonstrating the antidepressant properties of 2R,6R-HNK in both naïve and stressed rats and, furthermore, a lack of effects in BDNF knock-out mice [145–147]. Despite the novelty of these findings, 2R,6R-HNK’s specific molecular target remains to be fully elucidated, with some of the findings in this study being disputed. For example, reports by the Hashimoto’s group did not observe antidepressant-like activity by 2R,6R-HNK after CSDS [148], and further reported antidepressant activity of R-ketamine via direct infusion into the PFC or in the hippocampus dentate gyrus, but not of 2R,6R-HNK in the learned helplessness model [149]. However, these studies failed to perform a dose-response for the metabolite to confirm the antidepressant efficacy. In addition, Susuki and colleagues reported that a high concentration of 2R,6R-HNK (50μM) does not act on NMDARs, and its effect on neurotransmission and known intracellular signaling are not mediated via NMDAR blockade [100]. These claims have been validated further in a recent study that used antidepressant doses of 2R,6R-HNK (10 mg/kg), and showed that NMDAR currents were unchanged by the metabolite [150].

The Zanos et al. findings have challenged the widely held view that the antidepressant effects of ketamine are mediated by NMDAR inhibition and thus created lots of enthusiasm in the field. Despite this excitement, there is still much uncertainty regarding the metabolites of ketamine and their contributions to antidepressant efficacy, and, to date, there is not sufficient evidence in the literature to support the potential clinical properties of 2R,6R-HNK, or to reject the role of the known NMDA-mediated antidepressant responses. Specifically, it is unclear whether R-ketamine, S-ketamine, and 2R,6R-HNK are acting separately, interacting, or exerting their effects at different points in time, or what are the precise neural pathways implicated in their effects. Although these reports contradict one another, these studies seem to converge on the fact that AMPARs are contributing to the antidepressant activity of ketamine in synchrony with NMDARs. It is crucial that more clinical trials are done on R-ketamine and the various metabolites to validate the claims found in preclinical studies.

6. Non-NMDA targets of Ketamine:

Ketamine is a “promiscuous” drug, and while the main focus of study has been its actions at NMDARs, at concentrations higher than those reported to sustain antidepressant effects, ketamine interacts with other neurotransmitter systems [14]. Until recently, ketamine has been extensively studied under the umbrella of its analgesic, anesthetic, and anti-nociceptive properties at doses that are significantly higher than the range currently used to treat MDD (i.e., 0.5–0.75 mg/kg infusion over 45 minutes) [14,151]. To put this in perspective, in patients receiving a therapeutic dose of ketamine, the plasma concentration is between 200–250 ng/mL, or about 1μM [45], while patients receiving ketamine at anesthetic doses would have plasma levels of ketamine approximating 10–100μM [152]. At these doses, ketamine will bind to “off target” sites and engage non-therapeutic systems (see Figure 2). Despite having low affinities for many of the major neurotransmitter systems at low-doses, ketamine still engages several circuits via activation of AMPAR and/or NMDAR by disinhibition, and this will be covered in subsequent sections. Going forward, it is crucial that studies focus on the receptor-binding properties of ketamine, its stereoisomers, and its metabolites specifically at the lower doses conferring antidepressant activity. This will better elucidate how and when the antidepressant effects are occurring.

6.1. Opioid System:

The analgesic properties of ketamine have made it a very popular research target in the study of pain management for decades [153]. Not only has ketamine been efficacious at reducing both cancer and postoperative pain, it has been safely used for pain management in children and adolescents [154]. The antinociceptive properties of ketamine are surprisingly not mediated though the opioid system, as most painkillers target, but via the NMDAR blockade [155]. Ketamine does, however, interact with all the opioid receptors at high concentrations and they are likely to contribute to the wide range of effects seen after ketamine exposure [156]. There are three known opioid receptors: mu (MOR), kappa (KOR), and delta (DOR). These receptor families are found in high densities within limbic regions of the brain known to mediate mood and responding for natural and drug rewards [156]. Mu receptors, in particular, are known to be responsible for regulating mood, resilience after CSDS [157], and mediating the rewarding properties of drugs of abuse (e.g. cocaine, amphetamine, morphine), while increased activity of KORs is associated with depression [158], and their blockade thought to attenuate drug reward-related responding [159] [160]. Given ketamine’s history as a drug of abuse, determining whether opioid receptor stimulation mediates its antidepressant effects is of great importance [161,162]. Although it has been established that NMDAR and MOR colocalize in brain and cross-talk to serve as mutual regulators [163–165], ketamine, at therapeutic doses, does not appear to possess strong affinity for any of the opioid receptors [14]; however, moderate affinity for the DOR (Kd ~ 1–4 μM) in guinea pig brain homogenate has been reported [166,167]. Though there is a scarcity of evidence for the metabolites of ketamine having an affinity for opioid receptors, it has been reported that S-ketamine possess a two- to three-fold higher affinity for both the MOR and KOR as compared to R-ketamine [167]. Interestingly, S-ketamine induces more psychomimetic effects than R-ketamine, and these effects have been hypothesized as potentially driven by S-ketamine recruitment of KORs [166]. In healthy subjects, pretreatment with a low dose (25 mg/kg) of the MOR antagonist naltrexone exacerbated the psychoactive effects of a subanesthetic dose (0.4 mg/kg) of ketamine without augmenting these effects in the presence of higher doses of ketamine [168]. Though naltrexone may not have any major effects in a normal system, it has been shown to dysregulate mood in individuals with substance abuse disorders [169]. Two highly publicized recent studies showed that, in humans, pretreatment with 50 mg of naltrexone ablates the antidepressant and anti-suicidal effect of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine i.v., thus implying that the antidepressant and anti-suicidal activity of ketamine is mediated through the opioid system [170,171]. Consequently, these studies have received some criticism as they had limitations that keep them from concluding an opioid system involvement in ketamine’s antidepressant action, but they have also raised concerns as ketamine acting via an opioid-mediated mechanism could potentially worsen the harm of current opioid drug epidemic [172]. Zhang and colleagues have shown that naltrexone itself does not possess antidepressant properties nor does it block the antidepressant action of ketamine in mice that undergo CSDS, or experience lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced stress [173]. In this study, the authors argued that S-ketamine should have greater antidepressant efficacy than R-ketamine in rodents if its antidepressant action was in fact modulated by the opioid system due to S-ketamine’s higher affinity for opioid receptors. Sanacora et al. additionally argues that normal opioid functioning is necessary for the antidepressant efficacy of ketamine, but it is not the sole mechanism of the drug’s effect [174]. The original report from Williams et al. utilized a small sample and failed to test a non-ketamine-treated naltrexone control group. Interestingly, ketamine’s induced dissociative effects in this study were not influenced by naltrexone and therefore not mediated via the opioid system. Furthermore, studies including veterans with MDD and alcohol use disorders showed that pretreatment with naltrexone did not prevent ketamine’s antidepressant effects [175]. There is still much to be elucidated about the involvement, if any, of the opioid system in ketamine’s antidepressant effect.

6.2. Monoaminergic System:

For the last half century antidepressant drug development has overwhelmingly targeted the 5-HT, DA, and NE systems [176]. Due to the delayed onset and lack of efficacy of classical antidepressants such as tricyclics or SSRIs, there has been a push to move away from these traditional targets [177]. Though ketamine has opened a new avenue of research for novel therapeutics, it shares many neurobiological outcomes (e.g. increased 5-HT levels) as do conventional antidepressants despite low affinities for monoaminergic receptors [178]. Understanding both the similarities and differences between these drugs will help pinpoint the main targets necessary for antidepressant action.

The serotonergic system has been the primary focus of depression research for the better part of the century. Evidence for the serotonergic hypothesis stems from studies showing that depletion of 5-HT precursor tryptophan induces depressive symptoms in recovered depressed patients [179], and lower levels of 5-HT levels found in brains of suicide victims [180]. Though SSRIs induce a rapid large efflux of 5-HT into the synapse, the antidepressant effects do not appear until several weeks of continuous treatment. Interestingly, and similarly to what is seen after fluoxetine treatment, systemic ketamine increases 5-HT release within the medial PFC (mPFC), and this is associated with an antidepressant-like response in rodents, despite ketamine not having a high affinity for the serotonin reuptake transporters (SERT) at therapeutic low-doses [181–185]. This effect was blocked via a tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor, parachlorophenylalanine (PCPA), which prevents 5-HT synthesis [184–186].

Though ketamine does not act on SERT at antidepressant doses, blocking excitatory activation of 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphé nucleus (DRN) prevents ketamine-induced 5-HT release in the mPFC [187]. Direct infusion of ketamine into the raphé nucleus does not cause this increase in 5-HT, indicating that activation of serotonergic DRN neurons is occurring via glutamatergic projections from the mPFC, lateral habenula, or hypothalamus. Additionally, activation of both AMPAR and α4β2- nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) in the DRN leads to increased 5-HT in the mPFC [187], suggesting a reciprocal connection between these two regions. It is unknown why preferential binding of ketamine to GABAergic interneurons in DRN does not disinhibit 5-HT neurons to increase 5-HT release in the mPFC. Some studies have reported that glutamatergic neurons from the mPFC preferentially innervate 5-HT neurons in the DRN and not the GABAergic interneurons. [188]. Given that direct ketamine infusion into the mPFC induces an increase of extracellular 5-HT, it can be postulated that ketamine is antagonizing GABAergic interneurons in the mPFC resulting in an increase in glutamate transmission that activates postsynaptic AMPARs in the DRN, and subsequently causing release of 5-HT in other regions that induce excitation in the PFC, such as the ventral hippocampus [189]. Future studies should utilize pharmacogenetic or optogenetic techniques to excite or inhibit specific cell-type and specific circuits innervating the DRN in wake rodents to replicate the antidepressant effects of ketamine and to mimic the subsequent intracellular signaling.

Study of the other monoamine systems in the context of ketamine’s antidepressant effect have not shown as clear results as the serotoninergic system. DA also has long been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression [190]. For example, DA and its metabolite plasma levels are inversely correlated with depressive symptom ratings [191,192]. Although balance of DA levels play a crucial role in the manifestation of depression, the role that DA plays in the antidepressant effect of ketamine is unclear. Ketamine interacts with DA receptors, with high affinity for DA type 2 (D2) receptors (55 nM) [193]; however, S-ketamine has a two- to three-fold higher affinity for D2 and NMDARs compared to the standard racemic mixture [178]. At subanesthetic doses, ketamine is known to increase dopamine levels in the frontal cortex [194]. Haloperidol, a D2 antagonist, blocks the antidepressant effect of ketamine in the FST, where D2/D3 agonists seem to enhance the effect of ketamine [195], suggesting that there does exist some synergistic activity between ketamine and DA receptor activity. Ketamine also increases spontaneous activity of dopaminergic hubs, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) [136], and increases the firing rate and burst firing of these VTA-DA neurons [196,197]. More recent work has shown that photoinhibition of D1-containing DA neurons in the PFC can block the antidepressant effects of ketamine [198]. Furthermore, DA release within the VTA is heavily modulated by lateral habenula glutamatergic input. More specifically, in this region, ketamine administration blocks NMDA-dependent burst activity, which in turn disinhibits the lateral habenula’s downstream targets, including the VTA [199]. It is important to note that the VTA also receives glutamate inputs from other regions as well, and it is possible that the same disinhibition mechanism, as hypothesized in the PFC, is induced by ketamine in other brain substrates.

6.2.1. Adrenergic System:

The adrenergic system’s involvement in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression has not been as well characterized as 5-HT. Similarly to other monoamines, NE imbalances have been observed in postmortem brains of depressed patients, and use of selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) alone, and in combination with SSRIs, has shown promise as an effective therapeutic option [200]. Further solidifying NE’s role, treatments with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy have been shown to increase the number of α1 adrenoceptors while reducing the number of β-adrenoceptors [201,202]. Agonists at the α2 receptors decrease hyperadrenergic states (i.e., cardiac stimulation) and the psychoactive effects (i.e., postanesthetic delirium) induced by ketamine (Levänen et al., 1995). There is evidence of an interaction between ketamine and α- and β-adrenoceptors [203] resulting in inhibition of NE transporter function [204], though only at anesthetic levels (~100μM) of ketamine. Inhibition of NE reuptake is also modulated in a stereoisomer-specific manner such that a high dose of R-ketamine only inhibits neuronal reuptake of NE, while S-ketamine inhibits neuronal and extra-neuronal NE uptake [205]. Furthermore, subanesthetic doses of ketamine evoke NE release in the hippocampus [206].

Preclinical studies using mice have shown that agmatine, an α2 receptor agonist and partial NMDA antagonist, may have antidepressant properties as measured in the FST, and that these effects are NMDA- and 5-HT-dependent, as depletion of tryptophan hydroxylase (rate-limiting enzyme for 5-HT) with PCPA blocked agmatine’s antidepressant effects [207]. Systemic administration of sub-anesthetic antidepressant doses of ketamine (10 or 25mg/kg) in rats did not increase NE in the DRN, but significantly increased NE in the mPFC at the 25 mg/kg dose [208]. This demonstrates that ketamine may not be acting ubiquitously on all adrenoreceptors, but perhaps preferentially acting on those connecting to the mPFC. Though much more work is needed to parse the role of NE in the mPFC, these studies confirm that ketamine causes indirect release of both 5-HT and NE in the mPFC, suggesting that an intact monoamine system may be needed for ketamine’s sustained antidepressant effects.

6.3. Cholinergic System:

An unusual suspect, the cholinergic system has been hypothesized as well in the manifestation of major depression, but far less studied as compared to monoamine and glutamate systems. The cholinergic hypothesis of depression states that depressive symptoms arise from hyperactivation of the cholinergic system [209]. High doses (~20 μM) of ketamine are known to inhibit muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) and to antagonize nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [144], though patch clamp studies in xenopus oocytes have demonstrated that ketamine has no observable inhibitory effect on α7-nAChR at antidepressant doses. [210]. This illustrates that ketamine is having an indirect effect on acetylcholine signaling to assist in inducing antidepressant responses.

Clinical trials have shown that treatment with scopolamine, a non-selective mAChR antagonist, induces antidepressant effects [211], and parallel antidepressant effects with scopolamine have been found in animal models [212]. Furthermore, co-treatment with sub-effective doses of ketamine (3 mg/kg) and scopolamine (0.1 mg/kg) in mice show efficacy as measured in the FST [213]. Interestingly, scopolamine’s antidepressant-like effects appeared to be modulated via an increase in phosphorylation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the PFC, as similarly observed after ketamine administration [210,212,214]. The ketamine metabolites R,S-dehydronorketamine (dHNK), 2S,6S-HNK, and 2R,6R-HNK are potent and selective inhibitors of the α7-nAChR, with little effect on α3β4-nAChR or NMDARs [144]. Intriguing is the evidence linking α7nAChRs with the parasympathetic nervous system and the inflammatory system, though this area of research has not been explored in the context of depression [215]. Together, these studies lend support to the hypothesis that decreasing acetylcholine neurotransmission can positively affect mood and that an interaction between ketamine and AChRs may contribute to the antidepressant effect.

6.4. Sigma receptors:

Having originally been misclassified as an opioid receptor, it is not surprising that there is a lack of understanding about Sigma receptors. Sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors are endoplasmic reticular proteins capable of acting as chaperones to promote activity of various proteins that have been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders [216]. Sigma-1 receptors modulate all major neurotransmitter systems and interact with inositol triphosphate (IP3), thus influencing Ca2+ signaling [217,218]. Most antidepressants, including SSRIs, tricyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, bind to sigma receptors [219]. In animals models, sigma receptor agonists, such as BD1047, can buffer stress-induced behavioral and physiological deficits, however, translation into clinical practice has been slow due to the off target effects seen after drug administration [220,221]. Presumably, sigma receptors play an antidepressant role via the potentiation of neurite growth factor (NGF) and subsequent neuroplasticity [217]. In vitro studies have shown that ketamine has relatively weak affinity for sigma receptors, and that antagonism of the sigma receptors cannot attenuate the antidepressant effect of ketamine [222]. These studies suggest that although sigma-1 receptors may modulate monoaminergic neurons in such a manner that confers antidepressant activity, they are not necessary for mediating the antidepressant effect of ketamine. More research is needed to determine the involvement of sigma receptors and how they interact within known circuits known to mediate antidepressant action.

6.5. Neuroinflammation:

Since the 1980s, clinicians have known that administration of the pro-inflammatory protein interferon-α for hepatitis-C can induce depressive symptoms in a subset of patients [223]. Since then, the neuroinflammation hypothesis of depression has gained traction due to the increasing number of studies showing that patients with inflammatory and chronic pain disorders often have comorbid mood-related disorders, such as MDD [224]. This is a bi-directional relationship in that about a third of those with MDD show elevated peripheral inflammatory biomarkers, even during remission of MDD symptoms [225,226]. In addition, a hypersensitive immune response can lead to altered neuronal processes and decline in healthy cell function, subsequently eliciting MDD symptomology [227]. Neuroinflammation is the brain’s response to injury/stress or disease [228], and this response can be mediated by glial cells and/or leukocytes which secrete inflammatory modulators [229]. In patients with MDD, circulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) [231] is also increased [232], and remission of depressive symptomology is associated with downregulation of these cytokines [231,233]. In clinical settings, low-dose ketamine has been shown to decrease IL-6 and IL-10, as well as levels of liver-induced C-reactive protein (CRP) [15]. Some studies show that chronic stress-induced increases in IL-6 or TNFα leads to an upregulation in indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), an enzyme that reduces tryptophan bioavailability for 5-HT synthesis and regulates tryptophan-derived kynurenine (KYN), a regulator of immune response and vasodilation [234]. KYN promotes production of quinolinic acid, which acts as an agonist to NMDARs and promotes excitotoxicity [234,235]. Indeed, postmortem tissue of suicide victims show increased IL-6 with increased levels of quinolinic acid in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) [236]. These findings suggest that low-grade inflammation (i.e., increased IL-6) induces production of quinolinic acid, which in turn acts on the glutamatergic system potentially leading to depression and increasing the propensity for suicidality [236].

Given that ketamine has been classically used as an anesthetic, most clinical and preclinical studies have used high doses to understand this drug’s effects on the immune system response. When administered at anesthetic doses (~100 μM), ketamine produces immunosuppressant effects via downregulation of TNF-α and IL-6 synthesis [239–242]. In a model of early-life stress, antidepressant doses of ketamine were able to block maternal separation-induced increases in TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 [243]. Furthermore, other studies have confirmed that antidepressant doses of ketamine lower inflammatory markers within the PFC and hippocampus of rats exposed to stress [244].

Dysregulation of oxidative/antioxidant balance can also lead to neuroinflammation and, subsequently, mood disorders [246]. In a study assessing the effects of co-administration of various antidepressants in combination with ketamine, it was found that the SSRI fluoxetine potentiated the antidepressant effect of ketamine as measured in the FST, an effect potentially mediated via an increase in the activity of the dismutase, an antioxidant superoxide known to have neuroprotective properties [247]. Thus, it is conceivable that ketamine’s antidepressant action arises, at least in part, from modulation of oxidative stress and, consequently, regulating inflammation. Ketamine has also been implicated in mediating immunosuppressive effects via inhibition of activator protein-1 (AP-1), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), and nuclear factor-kB (NFκB), which can act as transcriptional regulators of inflammation-related genes [248–250]. Interestingly, there is some evidence indicating that ketamine may modulate inflammatory processes in a stereoisomer-specific manner as well. Antidepressant doses of R- ketamine decreases the concentration of bone marrow inflammatory markers such as steoprotegerin, NFκB, and osteopontin after exposure to CSDS, while S-ketamine has no effect [251]. Together, these findings along with those by Hodes et al. support the premise that the efficiency of an antidepressant may correlate with an individual’s inflammatory profile prior to starting treatment. For example, levels of adiponectin, an adipose-released cytokine involved in the anti-inflammatory response [248], correlated with a positive antidepressant response after just a single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg over 45min) [15,252]. This evidence further demonstrates that depression is marked by metabolic and inflammatory dysregulation [252]. It is important to note that there is some disagreement within the field regarding support for the immune hypothesis as cytokine levels do not correlate with antidepressant effects of a subanesthetic dose of ketamine in patients with MDD or bipolar disorder [253]. To this end, there have been some studies conducted using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) concurrently with SSRIs or tricyclics in order to better manage the inflammatory aspect of MDD [254]. These studies so far have had mixed results and are still ongoing. While the available data may suggest that the immune system may not be the primary target of ketamine’s antidepressant response, there is a strong relationship between immune state and mood, and further studies are warranted.

7. Neurobiological and molecular effects of ketamine:

The known pharmacokinetics of ketamine (i.e., metabolized with 2–3 mins, clearance within 24hrs) suggest that its short- and long-term antidepressant effects may arise from activation of complementary, yet distinct, systems at different times [30]. For example, glutamatergic receptors and other ion channels appear to induce faster biological changes and, subsequently, rapid antidepressant responses, while the long-term antidepressant effects of ketamine are most likely mediated by intracellular signaling cascades affecting a wide range of processes, including epigenetic modifications, neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation [255]. Understanding the short- and long- term intracellular signaling changes in response to antidepressant doses of ketamine are key to developing of new therapeutics devoid of potential negative side effects. Because a large body of research indicates that MDD has the most detrimental deficits within limbic regions of the brain, the following sections will cover how some key depression-related molecules are regulated by ketamine within the PFC, nucleus accumbens (NAc), hippocampus, and the VTA.

7.1. Ketamine-induced changes in synaptic plasticity:

The exact manner by which ketamine produces an antidepressant response remains unclear, but it does appear to alter major intracellular signaling cascades that promote synaptogenesis [256]. Deficits in dendritic spine stability and function are thought to play a major role in depression [18]. Indeed, imaging, gene profiling, and postmortem studies point to a reduction in brain volume, as well as decreased density and size of neurons within the PFC in patients with MDD, deficits believed to be caused by decreased synaptic functioning [257]. Preclinical investigations have demonstrated that stress exposure induces reductions in density of dendritic spines along with a decrease in the number and length of dendritic branches within the PFC [258,259]. In contrast, administration of ketamine completely reverses the effects of stress on dendritic spines, producing a rapid increase in the function and number of dendritic spine synapses [20]. This suggests that ketamine exposure leads to increased synaptic efficiency, which is thought to promote dendritic spine formation and restore normal physiological functioning, and consequently improve depressive symptomology [18]. This proposed mechanism of ketamine’s action lends further support to the glutamate hypothesis of depression which posits that excess glutamate release leads to excitotoxicity, causing a reduction in dendritic spine health, density, and functioning.

7.1.1. eEF2 + BDNF:

It has been postulated that disinhibition of GABA interneurons by ketamine elicits glutamate release in the PFC. We now know that the sequence of events does not stop there, and increased levels of glutamate can then activate postsynaptic AMPARs, resulting in a cascade of various intracellular signaling pathways. In vitro studies have reported that blockade of NMDARs at rest can decrease Ca2+-dependent tonic phosphorylation of the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) via eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K). More specifically, ketamine increases protein synthesis by deactivation of eEF2K. Once deactivated, the “translational brake” is lifted, causing rapid synthesis of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [54,120,260,261]. However, not all NMDAR antagonists promote activity of eEF2 or BDNF. Memantine, for example, does not appear to engage rapid synthesis of BDNF, which can be attributed to its lack of antidepressant efficacy in humans [262]. Interestingly, in vitro studies show that unlike ketamine, monoamine-based antidepressants do not cause a release of BDNF from primary cortical neurons [263] despite inducing an increase in BDNF mRNA [264]. BDNF binds to the TrkB receptor, initiating a series of signaling cascades mostly involved in the regulation of neuronal maturation and synaptic plasticity [8,120,265]. BDNF also increases AMPA translocation to the synaptic plate, possibly potentiating the effect of ketamine [266]. Other inhibitors of eEF2K that promote BDNF translation show antidepressant efficacy, and BDNF knockout mice fail to exhibit antidepressant effects after ketamine exposure, suggesting that BDNF is required for its antidepressant response [54]. Considering that typical antidepressants are not fast-acting and do not affect BDNF release [267], perhaps ketamine’s rapid onset can be attributed to this phenomenon.

7.1.2. mTOR:

One of the leading theories regarding ketamine’s ability to alter synaptogenesis and produce antidepressant effects involves activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [18]. mTOR is a ubiquitously expressed kinase known to regulate the initiation of protein translation, including new protein synthesis that is required for synaptogenesis [261]. mTOR has various upstream regulators, one of primary interest is the protein kinase B (AKT). AKT can phosphorylate the mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1), causing it to become activated. Once stimulated, the mTORC1 activates the p70S6 kinase (p70S6K) through phosphorylation, and then represses the inhibitory 4E binding proteins (4E-PB). This concert of events produces an increase in the translation of synaptic proteins promoting synaptogenesis. AKT has been directly implicated in maladaptive neurobiological response to chronic stress. Pharmacological reduction in AKT leads to an increase susceptibility to CSDS and increased firing frequency of VTA DA neurons in mice, a hallmark feature of stress susceptibility [268]. Another upstream regulator of mTOR is the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), which is activated by BDNF release consequently resulting in increased synaptic plasticity [18]. Chronic unpredictable stress exposure induces upregulation of ERK2 in the VTA promoting depressive-like behaviors, whereas treatment with the SSRI fluoxetine downregulates ERK2 [269]. Furthermore, viral-mediated upregulation of ERK2 in the VTA increases susceptibility to stress, whereas viral-mediated blockade of ERK2 activity increases resiliency to stress as measured by the FST, elevated plus-maze and the tail suspension tests [270]. Inhibition of kinases that are upstream of mTOR, such as ERK or AKT, prevents ketamine-induced phosphorylation of mTOR, p70S6k, and 4E-BPs, preventing an antidepressant response [20]. There is, however, some dispute between preclinical and clinical studies when using rapamycin, a selective inhibitor of the mTORC1. In rodent models, rapamycin completely abolished the induction of synaptic proteins as well as spine formation following ketamine exposure, suggesting that increased ketamine-induced synaptogenesis is dependent on activation of the mTORC1 complex [20]. On the other hand, the results from a recent small double-blind study showed that pretreatment with rapamycin (6 mg) prolonged the antidepressant effect of an acute ketamine infusion (0.5mg/kg) up to 2 weeks [271]. Though these findings would benefit from further replication and more statistical power, the study reinforces the role of mTOR in ketamine’s antidepressant effect, though surprisingly in the complete opposite direction from the preclinical findings.

Given mTOR’s critical involvement in protein synthesis, ketamine may promote the induction of mTOR signaling to sufficiently increase translation of synaptic proteins. This suggests that while stimulating BDNF release may produce rapid antidepressant effects, they may not be sustained without the induction of mTOR. The increased release of BDNF that occurs 30 minutes after ketamine administration appears to support this notion because it coincides with the induction of mTOR signaling [20,54]. However, pretreatment with rapamycin did not alter the antidepressant effects of ketamine when mice were tested 30 minutes after ketamine exposure [54]. This suggests that the rapid effects of ketamine may not be completely dependent on mTOR signaling, and instead are related to the rapid increased release of BDNF. Nevertheless, these findings do not preclude the likelihood of a mechanistic overlap to produce the sustained effects seen with ketamine. For example, in the PFC, the increased glutamate, BDNF, and mTOR levels observed after ketamine treatment return to basal levels after about 2 hrs [20,54,112], while the elevated synaptic protein levels are detected after about 2 hrs after ketamine administration, and they last for up to 7-days [20]. This chain of events closely resembles the time course of therapeutic effects observed in clinical and preclinical studies [29,30,54]. It is plausible then that the sustained antidepressant effects of ketamine are more dependent on induction of mTOR signaling, which results in a sustained increase in the synaptic proteins that promote synaptogenesis. Even so, there are several caveats to this hypothesis, as some studies have shown that BDNF may not play a major role in ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects. Ketamine and AMPAR potentiator LY451646 were able to induce rapid antidepressant efficacy in BDNF-knockout mice [272]. Furthermore, pretreatment with AMPA antagonists, before ketamine administration, blocks ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy and prevents the upregulation of BDNF and mTOR in the hippocampus and PFC, solidifying AMPARs importance in antidepressant efficacy [273].

7.2. GSK3β: