Abstract

Objectives:

Approximately 14% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted to a hospital within 30 days of home health care admission. Individuals with dementia account for 30% of all home health care admissions and are at high risk for readmission. Our primary objective was to determine the association between dementia severity at admission to home health care and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions (PPR) during home health care. A secondary objective was to develop a dementia severity scale from Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) items based on the Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST).

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and participants:

Home health care; 126,292 Medicare beneficiaries receiving home health care (July 1, 2013eJune 1, 2015) diagnosed with dementia (ICD-9 codes).

Measures:

30-day PPR during home health care. Dementia severity categorized into 6 levels (nonaffected to severe).

Results:

The overall rate of 30-day PPR was 7.6% [95% confidence interval (CI) 7.4, 7.7] but varied by patient and health care utilization characteristics. After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the odds ratio (OR) for dementia severity category 6 was 1.37 (95% CI 1.29, 1.46) and the OR for category 7 was 1.94 (95% CI 1.64, 2.31) as compared to dementia severity category 1/2.

Conclusions and implications:

Dementia severity in the later stages is associated with increased risk for potentially preventable readmissions. Our findings suggest that individuals admitted to home health during the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias may require greater supports and specialized care to minimize negative outcomes such as readmissions. Development of a dementia severity scale based on OASIS items and the FAST is feasible. Future research is needed to determine effective strategies for decreasing potentially preventable readmissions of individuals with severe dementia who receive home health care. Future research is also needed to validate the proposed dementia severity categories used in this study.

Keywords: Potentially preventable readmissions, dementia, home health care

In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries were discharged to postacute care following an inpatient hospitalization.1 Approximately 45% of beneficiaries who receive post-acute care are discharged to home health, which is the second most frequent among post-acute care sites.2 There are nearly 12,000 home health agencies (HHAs) in the United States,1 and 3.5 million beneficiaries received home health in 2016.1 HHAs provide care for homebound patients who temporarily need skilled nursing or therapy services.3

Increasing attention is being given to the quality of care provided by HHAs. In 2016, 12.2% of home health patients required emergency department care and 16.2% were hospitalized during the first 60 days of care.4 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has emphasized reducing the rate of unplanned readmissions during the first 30 days of home health.5 Approximately 14% of beneficiaries are rehospitalized within 30 days of starting home health.6 Many of these readmissions may be avoidable or prevented.7,8 CMS defines readmission as potentially preventable if the readmission is due to poor management of a chronic disease, infection, or an unplanned event.9 These readmissions may reflect poor quality of care.9–11

Population aging has led to an increase in the number of older adults living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).12 Individuals with ADRD experience twice as many health care transitions than older adults without ADRD.13 This includes greater use of home health services.13,14 Individuals with ADRD account for 30% of all home health patients.15 The majority of older adults with ADRD who use home health are already living at home, but approximately 25% are in the hospital before starting home health.16

Individuals with ADRD are a high-risk population for readmission.17–19 Little research has investigated readmission rates for older adults with ADRD who have been discharged from the hospital to home health.13 In an analysis of approximately 4000 older adults, fewer than 5% of older adults with ADRD discharged home with home health services were rehospitalized within 30 days compared with 8.6% for older adults with ADRD discharged home without home health services and 10.2% for older adults with ADRD discharged to a nursing home.13

Prior research on health care readmissions for older adults with ADRD has typically used International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification CodeseNinth Revision (ICD-9) codes to identify patients with ADRD. This approach is not able to differentiate among mild, moderate, and severe ADRD because Medicare claims data do not provide information on cognitive, behavioral, and functional characteristics. However, such information is available in the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS). The OASIS is used to collect information on a home health patient’s demographics, health and functional status, and health care needs.20 The OASIS includes items that may be useful for staging ADRD, such as cognitive function, ability to express ideas and understand verbal communication, and being able to complete daily activities.

Assessments are routinely used in clinical settings to evaluate ADRD staging and often include items that are similar to those in the OASIS. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) is a reliable and valid method for staging individuals with dementia across care settings.21,22 The FAST scale includes 7 categories that range from no clinically observable symptoms (stage 1) to severe ADRD (stage 7). For this study, we developed dementia severity categories by matching items from the OASIS to items within the FAST scale categories. The purpose of the study was to determine if the risk for a 30-day potentially preventable readmission (PPR) for home health patients with ADRD varies according to disease severity. We hypothesized that home health patients’ risk of 30-day PPR would increase with increasing levels of disease severity.

Methods

Data

Data came from 100% national CMS data files from July 1, 2013 through June 1, 2015: Home Health Base file, OASIS, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), and Beneficiary Summary files. The Home Health Base file was used to identify the cohort and to confirm the start and end of home health episodes. Data from the OASIS file were used to create the dementia severity scale. The MedPAR file was used to identify index hospitalizations, dementia codes, and readmission. The Beneficiary Summary file was used to verify Medicare Fee for Service enrollment and to obtain sociodemographic information. This study was approved by our university’s institutional review board. A Data Use Agreement was reviewed and approved by CMS.

Patient Cohort

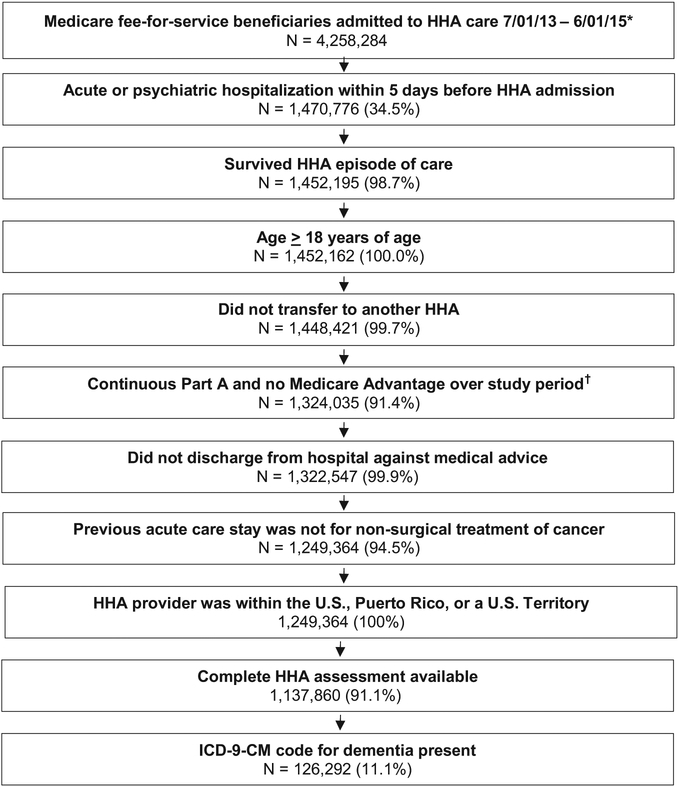

Criteria from the Home Health Claims-Based Rehospitalization Measure and the Potentially Preventable 30-day Post Discharge Readmission Measure for Home Health Quality Reporting Program were used to identify our cohort from 4,258,284 Medicare beneficiaries (Figure 1).6,9 Individuals who were not admitted to home health within 5 days of discharge from an acute or psychiatric hospitalization were excluded from the study. Individuals who did not have continuous coverage for 12 months prior to the index hospitalization and 32 days after the hospital discharge were excluded. Individuals whose home health provider was outside of the United States, Puerto Rico, or a US territory, and those who were transferred between home health agencies were excluded. Individuals were excluded if they were under the age of 18 years, did not have a dementia diagnosis (see Dementia diagnosis), or were missing administrative data necessary to identify a dementia diagnosis. Individuals who were discharged from the acute care hospitalization against medical advice or died during the home health episode and whose index hospitalization was for nonsurgical treatment of cancer were excluded. Individuals who were missing the variables of interest on the OASIS were excluded. The final cohort included 126,292 individuals.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting cohort selection at each step as exclusion criteria were applied. Percentages represent percent remaining from previous step. *First admission was selected if patient had more than 1 between 7/01/2013 and 6/01/2015. †“Study period” refers to the 1 year prior to the index hospitalization through the 32 days postdischarge for each index hospitalization. ‡Percentages indicate the percentage of the cohort that remained after application of the identified exclusion criteria.

Dementia Diagnosis

Beneficiaries with dementia were identified using the twentythree ICD-9 codes included in the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithm for Alzheimer’s disease, related disorders, or senile dementia (Supplemental Table 1).23 Beneficiaries with 1 or more ICD-9 codes for dementia in a Medicare Part A, home health, skilled nursing, or inpatient rehabilitation claim in the past year were classified as having dementia.

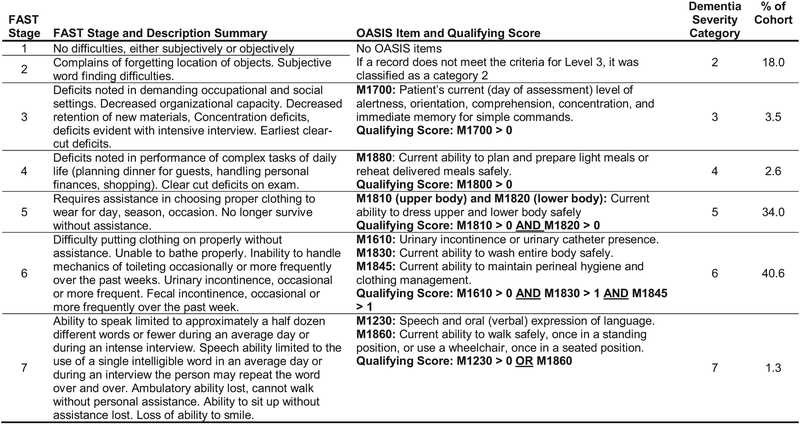

FAST

The predictor variable of interest for this study was dementia severity. For this study, dementia severity was divided into 6 categories. These 6 categories were based on the 7 stages of the FAST.24,25 We developed a cross-walk to match OASIS items to the descriptors for each of the stages of the FAST (Figure 2). The first (ie, lowest) dementia severity category represented FAST stages 1 and 2. At stages 1 and 2, symptoms are not clinically observable or reported by patients, making it appropriate to group these stages together. The remaining 5 dementia severity categories aligned directly with the remaining 5 stages of the FAST.

Fig. 2.

Crosswalk depicting the alignment of FAST Stage and corresponding descriptions to OASIS Items and the levels of OASIS items used to create dementia severity categories.

We used an iterative process of clinical decision making and examining frequency distributions to determine the appropriate OASIS items to align to the FAST stages. The goal was to identify the OASIS items and levels most representative of the FAST description for each stage. We were cognizant of the fact that we were looking for changes due to dementia progression, not due to other physical disabilities. Given the sequential nature of the FAST, we carefully examined which OASIS items were stopping patients from progressing upward in the dementia severity categories and considered the clinical application of the OASIS items to determine if adjustments were needed.

The dementia severity categories that we created for stages 5, 6, and 7 each use multiple OASIS items as qualifying criteria. For dementia severity category 5, the focus is on the patient’s ability to dress. The FAST does not separate ability to dress the upper body from ability to dress the lower body, but the OASIS does. Combining the 2 OASIS items (M1810 and M1820) that address the ability to dress the upper and lower body was more representative of the intent of FAST stage 5 description of patient impairment with dressing. For dementia severity category 6, 3 OASIS items (M1610, M1830, and M1845) best captured the intent of FAST stage 6 description. These items address incontinence, ability to bath, and ability to maintain personal hygiene. For dementia severity category 7, we identified 2 OASIS items (M1239 and M1860), both of which independently matched the criteria for the FAST stage 7 descriptors. These OASIS items address a patient’s ability to speak and ability to ambulate, 2 distinctly different functional abilities. Declines in 1 or both functional abilities can indicate a significant progression of dementia severity. Therefore, the qualifying criteria for dementia severity category 7 was met if either of these OASIS items reached a specified leve1.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was the occurrence of a potentially preventable readmission within 30 days of starting home health. The 30-day observation window was determined by adding 30 days to the “from” date in the first home health claim. We used the criteria described in the 30-day PPR Post Discharge Readmission Measure for Home Health Quality Reporting Program to identify PPRs that occurred within 30 days of starting home health.9 Potentially preventable readmissions were determined by comparing the admitting diagnosis of the readmission to the list of ICD-9 codes for diagnoses that were considered to be potentially preventable.

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race and ethnicity, Medicare original entitlement, and dual eligibility status. Health care utilization characteristics included comorbidities based on CMS hierarchical conditions categories,26 receipt of dialysis during hospitalization, length of index hospitalization, days in the intensive care unit or critical care unit, and the number of acute care stays over the previous year.

Data Analysis

For each patient characteristic, we calculated 30-day PPR rates, with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values for the univariate effect of each variable. We used multilevel logistic regression to study the relationship between dementia severity and PPR, adjusted for patient characteristics. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for each level of the FAST scale. Data analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 126,292 individuals in the sample, 65% were older than 81 years, 61% were female, and 80% were white (Table 1). Eighteen percent of patients were in the lowest dementia severity category (stage 2), and less than 4% were classified as stage 3. Thirty-four percent of patients were classified as stage 5, 41% were classified as stage 6, and less than 2% were classified in the most severe dementia category (stage 7).

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics and Observed Rates of 30-Day PPR During Home Health.

| Cohort Characteristics | Overall Sample n (%) | Observed Rate of Readmission, % (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 126,292 | 7.6 (7.4, 7.7) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–65 | 3324 (2.6) | 8.0 (7.1, 8.9) | |

| 66–70 | 6430 (5.1) | 7.2 (6.6, 7.9) | |

| 71–75 | 12,332 (9.8) | 7.4 (6.9, 7.8) | |

| 76–80 | 21,255 (16.8) | 7.4 (7.0, 7.7) | |

| 81+ | 82,951 (65.7) | 7.6 (7.5, 7.8) | .35 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 47,765 (37.8) | 7.8 (7.6, 8.0) | |

| Female | 77,527 (61.4) | 7.4 (7.2, 7.6) | <.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 101,062 (80.0) | 7.3 (7.2, 7.5) | |

| Black | 14,010 (11.1) | 8.5 (8.0, 8.9) | |

| Hispanic | 7262 (5.8) | 8.5 (7.9, 9.2) | |

| Other | 3958 (3.1) | 7.9 (7.1, 8.7) | <.00 |

| Medicare original entitlement* | |||

| Age | 109,900 (87.0) | 7.4 (7.2, 7.5) | |

| Disability | 15,873 (12.6) | 8.6 (8.2, 9.1) | |

| ESRD | 217 (0.2) | 9.7 (5.8, 13.6) | |

| ESRD and disability | 302 (0.2) | 15.6 (11.5, 19.7) | <.00 |

| Dual eligibility† | |||

| No | 99,918 (79.1) | 7.2 (7.1, 7.4) | |

| Yes | 26,374 (20.9) | 8.8 (8.4, 9.1) | <.00 |

| Dialysis during index hospitalization | |||

| No | 126,240 (99.9) | 7.6 (7.4, 7.7) | |

| Yes | 52 (0.1) | 9.6 (1.6, 17.6) | .57 |

| Index hospitalization length of stay, d | |||

| 1–2 | 31,028 (24.6) | 5.8 (5.6, 6.1) | |

| 3 | 24,715 (19.6) | 6.4 (6.1, 6.7) | |

| 4 | 19,097 (15.1) | 7.5 (7.2, 7.9) | |

| 5 | 13,518 (10.7) | 8.1 (7.6, 8.6) | |

| 6–7 | 16,592 (13.1) | 8.8 (8.4, 9.3) | |

| 8+ | 21,342 (16.9) | 10.0 (9.6, 10.4) | <.00 |

| Index hospitalization ICU/CCU utilization, d | |||

| 0 | 82,415 (65.3) | 7.1 (6.9, 7.3) | |

| 1–2 | 16,794 (13.3) | 7.0 (6.6, 7.3) | |

| 3–4 | 14,068 (11.1) | 7.9 (7.5, 8.4) | |

| 5+ | 13,015 (10.3) | 10.9 (10.3, 11.4) | <.00 |

| Acute stays over prior year (count) | |||

| 0 | 69,307 (54.9) | 2.5 (2.4, 2.5) | |

| 1 | 31,642 (25.1) | 10.0 (9.7, 10.3) | |

| 2 | 13,654 (10.8) | 15.0 (14.4, 15.6) | |

| 3 | 6022 (4.8) | 19.1 (18.1, 20.1) | |

| 4+ | 5667 (4.5) | 25.2 (24.1, 26.4) | <.00 |

| Dementia severity category at HHA admission‡ | |||

| 2 | 22,749 (18.0) | 7.2 (6.9, 7.6) | |

| 3 | 4455 (3.5) | 5.7 (5.0, 6.4) | |

| 4 | 3345 (2.6) | 5.6 (4.8, 6.3) | |

| 5 | 42,928 (34.0) | 6.4 (6.2, 6.6) | |

| 6 | 51,215 (40.6) | 8.8 (8.5, 9.0) | |

| 7 | 1600 (1.3) | 12.6 (11.0, 14.3) | <.00 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ICU/CCU, intensive care unit/critical care unit; RA, readmission

Original reason for Medicare enrollment.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Dementia severity categories were developed by aligning OASIS items to the FAST.

The overall 30-day PPR rate was 7.6% but varied significantly by patient characteristics (Table 1). Readmission rates ranged from 5.6% to 12.6% across the dementia severity categories. The highest readmission rate (12.6%) occurred for individuals in dementia severity category 7, followed by those in category 6 (8.8%). The lowest readmission rates occurred in dementia severity categories 3 (5.7%) and 4 (5.6%). Readmission rates were higher for dual eligible patients (8.8%) compared with non–dual eligible patients (7.2%) and increased with greater length of stay and number of days spent in the ICU. The largest difference in 30-day PPR rates were according to the number of acute hospital stays in the prior year. Patients with 4 or more stays had a 30-day PPR rate of 25.2% compared to 2.5% for patients with no other acute stays the previous year.

Odds ratios for 30-day PPR according to dementia severity categories adjusted for patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. Patients in dementia severity categories 3 (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.83,1.10), 4 (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84, 1.16), and 5 (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99, 1.13) did not have significantly different odds for 30-day PPR compared with patients in dementia severity category 2. Patients classified in dementia severity categories 6 (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.29, 1.46) and 7 (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.64, 2.31) had significantly higher odds for 30-day PPR compared with those in dementia severity category 2.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Risk of Readmission Based on Dementia Severity Category at Admission to Home Health Care

| Dementia Severity Category* | OR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 2 | Reference |

| 3 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.10) |

| 4 | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) |

| 5 | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) |

| 6 | 1.37 (1.29, 1.46) |

| 7 | 1.94 (1.64, 2.31) |

Dementia severity categories were developed by aligning OASIS items to the FAST.

Odds ratios from multilevel models adjusted for patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

Discussion

Our primary objective was to assess the risk of 30-day PPR for home health patients with a diagnosis of ADRD according to dementia severity. Our study provides important data on the 30-day PPR rates for a high-risk population that frequently receives home health services. The overall 30-day PPR rate in our sample was 7.6%. This rate is higher than the reported readmission rate of 5% for individuals with ADRD during home health.13 The differences in these rates are likely due to differences in methodology used to identify patients with dementia and in the methods used to determine readmission rates.

Returning to the hospital can be highly burdensome for patients with ADRD.27,28 Transitioning individuals with ADRD to new health care settings is associated with functional decline, infections, and communication errors.13,29–31 Additionally, hospitalizations among individuals with ADRD have been associated with increased cognitive decline,32 delirium,33 and medication errors.34 Hospitalizations can have lasting consequences for individuals with ADRD. A study of 263 ADRD patients revealed that patients who developed delirium while in the hospital experienced greater cognitive decline over a 5-year period than patients who not develop delirium.35

Historically, studies of individuals with ADRD using administrative data have been unable to assess dementia severity. This is a substantial challenge to investigating the health care utilization among individuals with ADRD.36 Our ability to approximate ADRD severity produced important insights into the characteristics and health care outcomes of individuals diagnosed with ADRD who are receiving home health. First, our results indicate that patients diagnosed with ADRD who are receiving home health following a hospitalization have a wide range of dementia symptoms. Medicare claims data has poor sensitivity for detecting mild cases of ADRD,23 but 22% of patients in our sample were classified as having early ADRD symptoms (stages 2 and 3). A study of 1 million Medicare beneficiaries found that approximately 28% of individuals receiving home health had either severe or significantly severe ADRD.37 Nearly 42% of patients in our sample had symptoms consistent with severe ADRD (stages 6 and 7).

It is difficult to compare the distribution of FAST categories from our sample with prior studies because most have used small samples of patients recruited from memory clinics,38 acute care,39 and from the community.40 Patients with greater symptom severity have been reported to be more likely to be discharged from the hospital to a nursing home.11,36 Our findings suggest that patients with severe dementia symptoms are receiving home health.

A second contribution is that we observed significantly greater risk for 30-day PPR with increasing dementia severity, but only for patients in the 2 most severe stages of dementia according to our classification scale. Patients with primarily cognitive symptoms of ADRD (stage 3) or who were limited in complex tasks (stage 4) had similar 30-day PPR rates to patients in the lowest severity stage. Patients classified as stage 6 and stage 7 had significantly higher odds for 30-day PPR. These 2 stages describe individuals who are unable to meet basic daily needs without considerable assistance, including putting on clothes, bathing, and toileting, and who have extreme difficulty communicating. Home health patients with severe ADRD may require more specialized care from therapists, family, and other support systems to prevent poor outcomes. Home health agencies are generally underprepared to provide care to individuals with ADRD.41 Educational programs have been found to be effective in increasing HHA nurses’ and therapists’ knowledge about how to care for individuals with ADRD.42 Continued efforts are needed to implement training interventions on a larger scale.

Finally, our univariate descriptive analyses identified demographic and clinical characteristics that are associated with high rates of 30-day PPR during home health. These included being Medicare eligible because of ESRD and disability (15.6%) and having 4 or more acute hospitalizations in the prior year (25.2%). These characteristics have also been associated with higher 30-day PPR rates after discharge from home health.43

Our analysis has limitations. First, we did not have a gold standard for ADRD severity to compare our classification using OASIS items. Future research can be done to administer the FAST scale in a home health setting to patients with and without ADRD. Second, we are not able to account for differences in how the OASIS is administered among HHAs and among clinicians within HHAs. The CMS published a detailed implementation manual describing how the OASIS should be administered in practice. However, there is likely variability in how items are interpreted and how information is recorded. This may have impacted the classification of patients into the different categories of ADRD severity. We also did not control for housing conditions, availability of social support, and other social determinants of health that may impact 30-day PPR rates during home health. Finally, a potential limitation of our analysis is we did not consider people with ADRD who were discharged to other settings, such as home without home health, a skilled nursing facility, or inpatient rehabilitation facility. Future research should investigate if the 30-day PPR rates according to ADRD severity vary by discharge setting.

Approximately 6% of patients were classified as stage 3 and 4. This low percentage may reflect differences in discharge disposition from the hospital for individuals in these stages vs other ADRD stages. Individuals in FAST stage 3 and 4 have fewer functional limitations, less severe behavioral and psychological symptoms, and are less likely to be homebound. Individuals in FAST stages 3 and 4 may be more likely to receive post-acute care services in an inpatient rehabilitation facility or through outpatient services. The low percentages may also reflect insufficient matching between the OASIS items and the FAST scale. Fast stage 3 describes difficulty in demanding occupational or social situations, such as organizational capacity, concentration deficits, and difficulty learning new information. Fast stage 4 describes difficulty with complex tasks such as cooking or grocery shopping. The description for these 2 stages emphasizes the decision-making process for complex tasks. The OASIS items that were used for stage 3 (M1700) and stage 4 (M1880) addressed similar topics described in these FAST stages but were assessed based on both cognitive and physical limitations. Similarly, insufficient matching between the OASIS items and the FAST scale may have resulted in an increased number of individuals classified as stage 2 (18%) as compared to stages 3 and 4. There is not a clear explanation for why this happened.

Conclusions and Implications

We observed an association between 30-day PPR and dementia severity among individuals with ADRD admitted to home health. Our findings suggest that individuals admitted to home health during the later stages of ADRD may require greater supports to minimize negative outcomes such as readmission. Further research is needed to determine what modifiable factors may decrease the risk of readmission for individuals with dementia during home health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HD069443; P2CHD065702; K01AG058789; U54GM104941) and the Foundation for Physical Therapy’s Center of Excellence in Physical Therapy Health Services and Health Policy Research and Training Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). June 2018 Databook: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian W. An all-payer view of hospital discharge to postacute care, 2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #205. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home Health Providers. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/HHAs.html. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Chapter 9: Home Health Services. Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2018 home health prospective payment system rate update and CY 2019 case-mix adjustment methodology refinements; home health value-based purchasing model; and home health quality reporting requirements. Fed Regist 2017;82: 51676–51752. To be codified at 42 CFR §484. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/11/07/2017-23935/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2018-home-health-prospective-payment-system-rate-update-and-cy. Accessed November 14, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acumen LLC. Home health claims-based rehospitalization measures technical report. 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Home-Health-Quality-Measures.html. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 7.Madigan E, Gordon N, Fortinsky R, et al. Rehospitalization in a national population of home health care patients with heart failure. Health Serv Res 2012; 47:2316–2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Carlson E, Popoola T, Suzuki S. The impact of rurality on 30-day preventable readmission, illness severity, and risk of mortality for heart failure Medicare home health beneficiaries. J Rural Health 2016;32:176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abt Associates. Measure specifications for measures in the CY 2017 HH QRP final rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-InitiativesPatient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/MeasureSpecificationsForCY17-HH-QRP-FR.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- 10.Goldfield N, Kelly W, Patel K. Potentially preventable events: An actionable set of measures for linking quality improvement and cost savings. Qual Manag Health Care 2012;21:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callahan K, Hartsell Z. Care transitions in a changing healthcare environment. JAAPA 2015;28:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hebert L, Weuve J, Scherr P, Evans D. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 2013;80: 1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callahan C, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu C, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare utilization and expenditures before and after the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimers Dementia 2015;11:P180. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 3 2016:x–xii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callahan CM, Tu W, Unroe KT, et al. Transitions in care in a nationally representative sample of older Americans with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63: 1495–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin P, Fillit H, Cohen J, Neumann P. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickens S, Naik AD, Catic A, Kunik ME. Dementia and hospital readmission rates: A systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2017;7:346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daiello L, Gardner R, Epstein-Lubow G, et al. Association of dementia with early rehospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014; 59:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Outcome and Assessment Information Set. OASIS-D Guidance Manual. 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/draft-OASIS-D-Guidance-Manual-7-2-2018.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2018.

- 21.Sclan S, Reisberg B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) in Alzheimer’s disease: Reliability, validity, and ordinality. Int Psychogeriatr 1992;4:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster J, Sclan S, Welkowitz J, et al. Psychiatric assessment in medical longterm care facilities: Reliability of commonly used rating scales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1988;3:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor D, Fillenbaum G, Ezell M. The accuracy of Medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auer S, Reisberg B. The GDS/FAST staging system. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reisberg B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ingber MJ, et al. Evaluation of the CMS-HCC risk adjustment model. Final report. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Evaluation_Risk_Adj_Model_2011.pdf; 2011. Accessed June 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruneir A, Fung K, Fischer H, et al. Care setting and 30-day hospital readmissions among older adults: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ 2018; 190:E1124–E1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao A, Suliman A, Vuik S, et al. Outcomes of dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital administrative database studies. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016;66:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gozalo P, Teno J, Mitchell S, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolph J, Zanin N, Jones R, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1542–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zekry D, Herrmann F, Grandjean R, et al. Does dementia predict adverse hospitalization outcomes? A prospective study in aged inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong T, Jones R, Shi P, et al. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2009;72:1570–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fong T, Jones R, Marcantonio E, et al. Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med 2012;156: 848–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeks L, Cooper G, Draper B, et al. Dementia, medication and transitions of care. Res Social Adm Pharm 2016;12:450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross A, Jones R, Habtemariam D, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2012;172: 1324–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane R, Ouslander J. Dementia as a moving target. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60: 980–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu C, Moore S, Murtaugh C. Development of a cohort of Medicare patients with advanced dementia. Alzheimers Dementia 2017;13: P1562–P1563. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisdorfer C, Cohen D, Paveza G, et al. An empirical evaluation of the Global Deterioration Scale for staging Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149: 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feast A, White N, Lord K, et al. Pain and delirium in people with dementia in the acute general hospital setting. Age Ageing 2018;47:841–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi Y, Won C, Kim S, et al. Five items differentiate mild to severe dementia from normal to minimal cognitive impairment—Using the Global Deterioration Scale. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2016;7:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brody A, Guan C, Cortes T, Galvin J. Development and testing of the Dementia Symptom Management at Home (DSM-H) program: An interprofessional home health care intervention to improve the quality of life for persons with dementia and their caregivers. Geriatr Nurs 2016;37:200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Middleton A, Downer B, Haas A, et al. Functional status is associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions following home health care. Med Care 2019;57:145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.