Abstract

Vendor-independent software tools for quantification of small molecules and metabolites are lacking, especially for targeted analysis workflows. Skyline is a freely available, open-source software tool for targeted quantitative mass spectrometry method development and data processing with a ten-year history supporting 6 major instrument vendors. Designed initially for proteomic analysis, we describe the expansion of Skyline to data for small molecule analysis, including selected reaction monitoring (SRM), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and calibrated quantification. This fundamental expansion of Skyline from a peptide-sequence centric tool to a molecule-centric tool makes it agnostic to the source of the molecule while retaining Skyline features critical for workflows in both peptide and more general biomolecular research. The data visualization and interrogation features already available in Skyline - such as peak picking, chromatographic alignment, and transition selection - have been adapted to support small molecule data, including metabolomics. Herein, we explain the conceptual workflow for small molecule analysis using Skyline, demonstrate Skyline performance benchmarked against a comparable instrument vendor software tool, and present additional real-world applications. Further, we include step-by-step instructions on using Skyline for small molecule quantitative method development and data analysis on data acquired with a variety of mass spectrometers from multiple instrument vendors.

Keywords: Skyline, metabolomics, liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry, small molecules, quantitative, targeted, metabolite, data analysis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Skyline is an open-source quantitative software tool originally implemented for targeted mass spectrometry (MS) proteomics workflows. Since its first public release in 2009, the Skyline software package has proven to be a highly reliable, flexible and widely used program for targeted SRM-MS analysis.1-3 Subsequently, additional Skyline features were developed to process data-dependent acquisition (DDA) files for quantification by using precursor ion extraction from high-resolution MS1 spectra.4, 5 Novel proteomics workflows have been implemented in Skyline as they have emerged and gained acceptance, such as parallel reaction monitoring (PRM)6, 7 and data-independent acquisition (DIA).8, 9 Skyline is currently being used by many thousands of researchers worldwide, predominantly for quantitative proteomics applications.10 While small molecule analysis via mass spectrometry has benefitted greatly from technological advances in mass spectrometry and separations science, there remains a need for data analysis with MS vendor-independent software tools that increase transparency and facilitate the translation of methods between labs and instrument platforms. Instrument manufacturers each have their own method development, data processing, and data analysis solutions. Though vendor software may provide advantages through insights into processing specific instrument data, these proprietary tools limit the transparency of data review by other laboratories that may not have access to the same commercial software, and limit translation of methods to other laboratories or even within the same laboratory using other MS platforms. The open-source software tool Skyline provides unique features and is especially known for its comprehensive visualization tools and sophisticated method refinement options such as retention time scheduling and collision energy optimization,11 that have been widely adopted in the proteomics field. These features are now also implemented for small molecule workflows such as metabolomics, pharmaceuticals (pharmacokinetics, drug metabolites, drug purity, toxicology), forensics, food safety and environmental pollutants.

In the field of open-source software for metabolomics, there are widely utilized packages for nontargeted analysis such as XCMS12, MZmine13, and MS-DIAL.14 However, for hypothesis-driven quantification of small molecules, Skyline is one of few widely-applicable open source tools, others of which include XCMS-MRM15 and MRMProbs.16 While Skyline can readily analyze datasets collected with both targeted (SRM and PRM) and nontargeted methods, Skyline differs from traditional nontargeted analysis tools in that it requires as a first step, that experiments be defined as a set of target molecules (or “hypotheses”) for analysis. Recent developments in Skyline for interrogation of proteomic data-dependent (DDA) and data-independent acquisition (DIA) experiments demonstrate that the number of analytes can be as many as several tens of thousands of peptides.4, 9,17 Nonetheless, specifically for metabolomics, it is important to discriminate between typical non-targeted workflows which start with feature-finding in MS1 spectra followed by alignment between runs and finally identification, versus the Skyline approach of extracting known targets followed by detection and quantification. Targeted MS data analysis packages typically allow the user to view raw LC-MS data in the form of extracted ion chromatograms for the evaluation of separation and peak integration, to adjust automatic peak integration as necessary, often accompanied by approaches utilizing stable-isotope dilution or external calibration to quantitatively calculate concentrations of compounds of interest (as applicable). The goal of this manuscript is to describe the extension of the targeted analysis paradigm using Skyline for small molecule workflows, and to present a comprehensive metabolomics tool, supporting six major MS instrument vendors, that promises valuable features and excellent analytical performance to the metabolomics community. Additionally, Skyline documents can be readily shared using Panorama via https://panoramaweb.org/, a web-based targeted method and data repository, which can serve as a powerful platform for rapidly translating small molecule methods and results between laboratories.18, 19

In this report, we demonstrate the utility of Skyline for metabolomics and metabolite quantification and describe experiments we used to examine its ability to process data from several instrument types, including triple quadrupole MS, such as the Xevo TQ-S (Waters), and the 5500 (SCIEX), and also high-resolution mass spectrometers, like the Synapt G2 HDMS (Waters). We first benchmark Skyline for targeted quantitative small molecule analysis using published data from the analysis of clinical samples with a well-established, commercial metabolomics kit (AbsoluteIDQ p180).20, 21 We next characterize a unique strength of Skyline by using it for the development and refinement of a customized assay for the targeted analysis of compounds in the arginine and polyamine pathways which utilizes ion pairing reagents and avoids classical derivatization.22-27 We further pursue an analysis of purine/pyrimidine compounds to evaluate the ability of Skyline to handle positive/negative switching small molecule data in a single project. Finally, we present an example of how to use Skyline to perform the extraction of small molecule targets for quantitative analysis in high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data.28 In addition, we have created several small molecule tutorials that provide step-by-step instructions on how to use Skyline for metabolomics analysis, covering topics which include i) method development and refinement, ii) calibrated quantification and iii) high-resolution metabolomics data analysis. The supplementary material contains a basic tutorial “Getting Started with Skyline for Small Molecules”, and more detailed tutorials are hosted, updated and synchronized with new developments on the Skyline website (https://skyline.ms/tutorials.url).

Experimental Methods

Materials

All solvents used were of LC-MS grade or better, acetonitrile, water and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA), or Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI). Reagents for metabolite chemistry and quantification kits are described below in the various assay sections.

Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 Analysis

Preparation of serum samples from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort and analysis of these samples by the Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 targeted metabolomics kit (Biocrates Life Science AG, Innsbruck, Austria) has been described previously by the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium (ADMC).20, 21 The data included in this report presents and discusses the reanalysis of the previously acquired raw mass spectrometric data from a single plate of 76 human serum samples.20, 21 No demographic or clinical data for the samples is included in the current manuscript; this can be obtained with permission from ADNI (adni.loni.usc.edu). Investigators within ADNI provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. Briefly, amino acids in the p180 kit are derivatized on filter paper using phenyl isothiocyanate (PITC), extracted in buffered methanol, and analyzed by reversed-phase LC-MS/MS using an Acquity UPLC coupled to Xevo-TQS mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation). In the published data20, 21, TargetLynx v4.1 was utilized for data analysis. The same curve fit (linear regression with 1/x weighting) and quantification parameters were utilized in Skyline-daily version 19.0.9.149 in this manuscript for the purposes of data visualization and processing. The Skyline document for this analysis has been uploaded to Panorama Public at https://panoramaweb.org/SkylineForSmallMolecules.url.

Polyamine Sample Preparation

The following unlabeled standards: agmatine, 5’-deoxy-5’-methylthioadenosine (MTA), S-(5’-Adenosyl)-L-methionine chloride (SAM), S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), spermidine (Spd), N1-acetylspermidine (N1-AcSpd), N8-acetylspermidine (N8-AcSpd), N1-acetylspermine (N1-AcSpm), N1-, N12-diacetylspermine (DiAcSpm), arginine (Arg), homocysteine (Hcy), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), ornithine (Orn), acetylputrescine (AcPut) and spermine (Spm) were obtained in small quantities from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The stable-isotope labeled internal standards N8-AcSpd-d3, N1-AcSpm-d3, MTA-d3, DiAcSpm-d6 and GABA-d6 were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON) and CDN Isotopes Inc. (Pointe-Claire, QC). All compounds were dissolved in vendor-recommended solvents to create stock solutions of individual compounds. A ten-point calibration curve of the mix of standards was prepared in the homogenization solvents over a range of 0.01-25 μM.

Cohort 1:

Urine was collected from thirteen 12-week old CVN mice29, following all proper IACUC protocols, for polyamine analysis and the samples were stored at −80 °C until sample preparation and analysis. The urine samples were removed from the −80 °C freezer and kept over ice during sample preparation. Two aliquots were removed from the original sample, 50 μL used for individual analysis and 10 μL used for the sample pool quality control (SPQC). For sample and calibration standard preparation, 20 μL of urine or calibration standard in PBS were removed and diluted with 40 μL of 1:1 MeOH:H20 containing a mix of internal standards. Samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 xg at 4 °C for 5 minutes. The supernatant was removed and transferred to a pre-labeled LC-MS Total Recovery Vial from Waters (Milford, MA).

Cohort 2:

Nineteen brain tissue samples from cognitively normal humans were acquired from the Specimen Repository of the Bryan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Duke IRB Protocol 00036140), under exemption based on de-identified samples, and kept at −80 °C until sample preparation and analysis. Samples were removed from the freezer and kept over ice during sample preparation; a variable volume of 67.8:14.2:17.8 MeOH:H2O:CHCl3 (v/v) spiked with heavy labeled internal standards was added to each Precellys CK14 tube containing pre-weighed brain tissue to normalize each sample to a constant tissue weight per volume of solvent (0.0657 mg/μL). The samples were homogenized using a Bertin Precellys 24 Tissue Homogenizer (Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) cooled to 4 °C with dry ice for three cycles of 10 seconds each at 28,000 xg and 1-minute rest in between cycles. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 xg held at 4 °C for 10 minutes. From each sample, a 50 μL aliquot of the supernatant was removed and transferred to a pre-labeled LC-MS Total Recovery Vial from Waters (Milford, MA).

Polyamine Analysis by LC-MS/MS

Skyline was used to develop and refine a custom method to measure polyamines and acetylated polyamines in urine and brain tissue. The assay used an Acquity UPLC interfaced to a Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation). Electrospray ionization was used with tune parameters: spray voltage 2.8 kV, desolvation gas 1000 L/hr, cone voltage 35 V, desolvation temperature 500 °C and cone gas flow 150 L/hr. From each sample, 1 μL was injected onto a 1.7 μm Acquity UPLC BEH C18 2.1 × 100 mm column (Waters Corporation Milford, MA). Mobile phase A was comprised of 0.1% v/v acetic acid (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.0125% v/v perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHA, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in water. Mobile Phase B was 0.1% v/v acetic acid and 0.0125% v/v PFHA in acetonitrile. The separation used a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1 and a column temperature of 40 °C. The chromatography program began with 1% mobile phase B and increased to 25% B over the first 1.5 minutes. The organic phase increased to 40% at 3.0 minutes and reached 99% at 4.0 minutes, was held for 0.7 minutes and decreased to starting conditions (1% B) at 4.8 minutes where it was held for 1.5 minutes until the end of the 6.3-minute analysis. Weak needle wash was comprised of mobile phase A, and to minimize carryover the strong needle wash was comprised of acetonitrile: methanol: isopropyl alcohol: water: formic acid (50:20:15:15:0.25). Skyline-daily versions 4.2.1.19004 and 4.2.1.19058 were used for LC-SRM-MS data analysis and processing. The Skyline documents for the mouse urine and human brain tissue analysis have been uploaded to Panorama Public at https://panoramaweb.org/SkylineForSmallMolecules.url.

Purines and Pyrimidines by LC-MS/MS

For the purine and pyrimidine analysis, we operated a SCIEX 5500 Triple-Quadrupole LC-MS mass spectrometer fitted with a Turbo V ion source, online connected to an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography Agilent 1260 UHPLC system. Analyst v1.6.1 (SCIEX) was used for all SRM data acquisition, the development of the HPLC method, and the optimization of analyte-specific SRM transitions. Skyline-daily version 4.2.1.19004 was used for LC-SRM-MS data analysis and processing.

For the purine and pyrimidine analysis, urine from five mice was collected from voluntary expulsion, and 20 μL aliquots were stored at −80 °C until ready for analysis. Urine aliquots were thawed on ice and 80 μL of methanol was added containing 2-chloroadenosine (IS) at a final concentration of 2.5 μM to each 20 μL urine aliquot. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for ~30 seconds and protein precipitation was completed by incubating at −20 °C for 30 min. After this, samples were vortexed vigorously for ~30 seconds and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. An 80 μL aliquot of the supernatant was carefully removed without disturbing the pellets and transferred to an HPLC autosampler vial fitted with inserts; 2 μL were injected per HPLC-SRM-MS analysis.

Synthetic standards for compounds indicated in Table S1 were obtained from IROA (Mass Spectrometry Metabolite Library of Standards, MSMLS) or Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. 100 μM stocks were prepared in 80% methanol and stored in −80 °C prior to use. A final standard mixture of all compounds at 5 μM (containing the internal standard/IS, 2-chloroadenosine at 2.5 μM), was prepared prior to analysis and injected at the onset of each set biological sample set. The Skyline document for urine purine/pyrimidine analysis has been uploaded to Panorama Public at https://panoramaweb.org/SkylineForSmallMolecules.url.

High Resolution Diacylglycerol Analysis

Demonstration of high-resolution precursor ion metabolomics data analysis utilized a previously published study of the lipidomic response of BT474 breast cancer cells to a fatty acid synthase (FASN) inhibitor, specifically examining the diacylglycerols.30 Briefly, lipids were extracted from BT474 cell pellets using MeOH/MTBE then analyzed using a reversed-phase nontargeted lipidomics method, including Acquity UPLC with a CSH C18 2.1 x 10 mm column coupled to a Synapt G2 HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation). Initial data analysis of this nontargeted lipidomics dataset was performed in Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation). Skyline 4.2 was utilized to confirm differential expression for two diacylglycerol (DAG) species, DAG 30:0 and DAG 32:0. Lockmass correction was enabled and performed within Skyline using Leucine-Enkephalin, [M+H]+ at m/z 556.2771. The Skyline document has been uploaded to Panorama Public at https://panoramaweb.org/SkylineForSmallMolecules.url.

Results

A broad variety of targeted workflows will be presented featuring some of the most valuable features of Skyline as a novel software tool for small molecules providing convenient, efficient assay development and data processing.

Skyline Small Molecule Quantification: Method Setup and Data Processing

Skyline was originally designed to support quantitative proteomics workflows.3 Herein, we describe new features which have been implemented to support targeted quantification from both targeted and nontargeted mass spectrometry data acquisition modes for small molecules. A Skyline document for small molecule analytes differs considerably from one for proteomics. Skyline provides a highly flexible environment for getting started with many types of small molecule quantification experiments, so much so that it has been used for proteomics cross-linking experiments.31 Prior to the release of Skyline for small molecules, multiple groups utilized Skyline and its flexible architecture for peptides to quantify lipids without the tool formally supporting it.32

Figure 1 shows a workflow and its key steps for method creation and utilization in Skyline for a small molecule targeted SRM quantification, including method setup, assay refinement, data acquisition and data processing. In order to support targeted quantification, the Skyline targets tree typically includes the name and at least the m/z and optionally the precursor ion formula of each analyte. The targets tree may also include empirical fragment ions (transitions) or transitions from a database or library. Examples of Skyline methods for small molecules typically include a simple list or set of lists of precursor and product ion m/z values for SRM experiments33-35, or exact masses for high-resolution precursor ion measurement.5 In all cases, the molecular formula of a molecule of interest may be provided, allowing the software to derive precise m/z values as well as isotope distributions for precursor and product ions; though, this is not required. Further, Skyline supports a wide variety of chemical adducts such as metal ions and volatile organics (i.e. ammonia and formate) and allows for both positive and negative ion charges. These adducts can be specified in a new Skyline Transition Settings-Filter Tab in Skyline (Figure S1) as well as at the time targets are added. There are also a variety of instrument- and method-specific parameters which can be explicitly defined at the beginning of the workflow, such as collision energy, retention time, cone voltage (Waters), declustering potential (SCIEX) and S-Lens (Thermo). These are available during target addition with the Skyline Edit->Insert->Transition List menu item and may also be set after addition through the Document Grid. The “Getting Started with Skyline for Small Molecules” tutorial in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Document S1) covers many of the basics described above and is the best place to start for new practitioners.

Figure 1.

A generalized workflow for small molecule analysis in Skyline

The second step in the Skyline targeted mass spectrometry workflow is to export a method, either in the form of a transition list in vendor-specific format, or as a native instrument method file. As for proteomics methods, exporting to a native instrument method file requires a ‘template’ method file, or default method of the correct format for the instrument that will run the method.

After initial method export, usually, a cycle of method optimization will follow including retention time scheduling, precursor and product ions selection, and collision energy optimization. The optimized method is then exported by Skyline and used to acquire mass spectrometry data on the biological samples, calibrators and quality controls. The resulting raw data is analyzed by peak integration and calibrated quantification. At this point, Skyline offers extensive visualization options and even the ability to manually adjust integration for data quality control. Finally, peak areas and quantitative metrics may be exported in a tabular report format, using a highly flexible export dialog. A set of small molecule tutorials have been written to describe this workflow in detail, and can be accessed in the Supplementary Material or on the Skyline website (https://skyline.ms/tutorials.url.

Novel Visualizations in Skyline Aid in Small Molecule Quantification

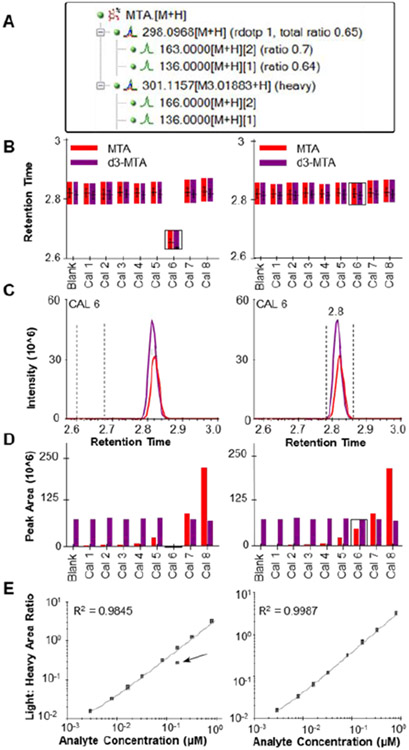

Like MS vendor software, data analysis starts in Skyline with importing the native instrument files and does not require these files to be converted to an open format. Therefore, after data collection, raw data can be imported directly back into the Skyline document used to export the instrument method for data viewing and further analysis. Skyline is uniquely designed for the user to easily observe retention time, SRM or extracted ion chromatograms, and peak areas for each compound and its heavy labeled isotope (if present) across numerous injections. A series of screenshots from Skyline are shown in Figure 2 in order to demonstrate several of the intuitive displays which allow for quick visual inspection of processed data and manual adjustment if necessary. Figure 2A shows the targets tree for 5’-methylthioadenosine (MTA), including the precursor and product ions for the native metabolite and d3-MTA stable isotope internal standard. The remaining panels of the figure show an example of how the data may appear if an integration error occurred (left pane, contrived example for file CAL 6) or was correct (right pane). Manual data review is one of the most time-consuming aspects of quantitative mass spectrometry. Figure 2B demonstrates how the replicate retention time view allows the user to quickly recognize an acquisition where an incorrect retention time window was integrated. A simple click on Cal 6 bar in this plot causes Skyline to show the chromatogram view (Figure 2C), where dashed lines indicate the integration window before and after corrected integration (left and right panes, respectively).

Figure 2.

Unique Skyline visualizations helpful for data interrogation. Left-hand panes demonstrate a hypothetical example of when incorrect retention time is selected for a single acquisition, while right-hand panes demonstrate correct integration. A) Skyline molecule tree for MTA showing precursor and product ions for the light and heavy isotopes B) retention time replicate display C) chromatogram traces for integrated MTA. The vertical lines indicate where the peak integration was placed D) peak area replicate display E) calibration curve display.

Figure 2D shows the replicate peak area view for the same example data. In calibrated quantification (i.e. using an external calibration curve), it is often useful to visualize the peak intensities of the internal standard for consistency among the samples and standards (shown in purple), as well as the peak intensity of the analyte of interest (shown in red). This view also allows the user to quickly identify an acquisition which may need manual inspection (left pane), and again navigate with a single click to the appropriate chromatogram pane and correct the peak integration as necessary (right pane). Finally, the calibration curve visualization in Skyline (Figure 2E) allows for facile exclusion or reintegration of calibration points which have high bias. Altogether, these visualizations represent features that can greatly improve accuracy in data analysis by making it easier to locate and adjust or exclude incorrect peak integrations or flag acquisitions which are suspect.

Validation of Skyline as a Tool for Calibrated Quantification

Skyline was recently used in a brief report on quantitative mass spectrometry assays for 25-hydroxy vitamin D and vitamin D binding protein from serum specimens, and was found to be equivalent to a vendor tool.36 While encouraging, this example showed a single small molecule analyte over a limited dynamic range. Therefore, we assessed a much larger data set for this report. The commercial Biocrates p180 analysis kit has been extensively characterized in small molecule analyses with many publications reporting values obtained from various biological matrices analyzed using the kit, together with the recommended vendor-specific software.37-39 Typically, the p180 data for the LC-MS/MS portion of the kit is processed in the vendor software of the instrument used for analysis, then imported into Biocrates MetIDQ for reporting. Because the p180 amino acids analysis by LC-MS/MS measures a number of analytes across a reasonably wide dynamic range (0.1-2000 μM) and is highly utilized in the community, we chose it as a testbed for evaluating the quantitative accuracy of Skyline. Serum amino acids from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort were previously collected using the p180 kit.20 Herein, we compared the reported concentration values between the two methods of data analysis in order to benchmark Skyline against TargetLynx (Waters) for this specific assay.

Concentrations were assessed for each of the 19 amino acids included in the Biocrates p180 assay that have corresponding internal standards, using TargetLynx and Skyline, across a set of 76 human serum samples. The raw data which was previously obtained via UPLC analysis for the ADNI cohort was loaded for reanalysis into a Skyline file (version 19.0.9.149) containing the amino acids and the transitions for the light and heavy isotopes where applicable. Peak picking was performed with explicit retention times and integrated automatically using the Skyline peak integration algorithm. Manual adjustments of peak area integration were only required for a small number of analytes due to differences in explicit retention time listed and the actual retention time as well as differences in retention time between the light and heavy isotopes of the analyte (some internal standards are deuterated). The concentrations for analytes were calculated using the ratio of light to heavy peak area response and a 7-point calibration curve with 1/x weighting covering 10^3 dynamic range; the calibration range for each metabolite varies from 0.1 to 2000 μM, depending on the expected analyte concentration range. Calibration points with greater than ±15% bias above the lower limit of quantification, or outside ±20% bias at the lower limit of quantification, were excluded.

Figure 3A shows a plot of the correlation between the concentrations reported by Skyline and TargetLynx for all 19 amino acids. A linear regression of these points yields a slope of 0.9837 (95% CI 0.9824-0.9850) and intercept of 0.041 μM (95% CI 0.037-0.045), with an R2 value of 0.9995. While these numbers indicate a very slight but statistically significant (at 95% confidence) difference from the ideal regression with slope of 1 and y-intercept of 0, the correlation coefficient is almost perfectly 1. The very slight difference between Skyline and TargetLynx reported absolute concentrations is almost certainly unimportant. Figure 3B displays the calculated accuracy of the concentration values reported via Skyline compared to TargetLynx for each individual analyte and sample in increasing order of average abundance. All of the compound concentrations reported via Skyline have a mean accuracy within 100± 3% accuracy of the published ADNI values, which were calculated with TargetLynx.20, 21 Aspartic acid (Asp), a lower abundance amino acid, has a notably larger standard deviation than the rest, and this is believed to be due to the software packages using different peak localization and integration approaches. Skyline does not apply boxcar smoothing of the chromatograms prior to peak area integration; the data for Asp suggests this difference in smoothing use may impact agreement between the two tools for low S/N analytes. Overall, Skyline performance appears to be nearly identical to the benchmark vendor tool for this particular p180 assay, suggesting users should feel confident in transitioning existing assays to Skyline, or developing new assays which utilize Skyline as the primary quantitative analysis tool.

Figure 3.

Comparison of clinical serum concentrations obtained for 19 amino acids in the Biocrates p180 assay. (A) Correlation of reanalysis of published data using Skyline results (x-axis) versus published concentrations measured in TargetLynx (y-axis) (B) Relative accuracy for each analyte comparing Skyline to published concentrations from TargetLynx, sorted low to high analyte concentration left to right.

High-Throughput Method Development using Skyline: Customized Polyamine Panel

Skyline was used to develop a customized polyamine assay targeting arginine-proline metabolism and its downstream polyamine metabolites. The polyamines and their acetylated forms have important biological implications in cancer and neurology, making their detection and quantification an area of interest.40-43 In this work, we used Skyline for custom method development, and subsequently to analyze LC-MS/MS data generated from human brain and mouse urine samples (also see workflow Figure 1). First, a transition list was imported into Skyline including the following molecules for quantitation and analysis: agmatine, hcy, GABA, MTA, spd, N1-AcSpd, AcSpm, arg, orn, AcPut, SAH, N8-AcSpd, SAM, spm, DiAcSpm (see Supplemental Table S2 for precursor and product ion information, collision energy, retention time and heavy labeled internal standard used for normalization). Following analysis of these molecules and their corresponding stable isotope labeled standards, a method was exported with retention time scheduling based on the measured retention times from the prior analysis and a time window setting of 1-minute centered on these times. The difference in concurrent transition counts using various (1, 2, 5, 20 minutes) retention time scheduling windows is shown in Figure 4A. With a scheduling window (20 minutes) set for longer than the total chromatographic time, all of the ion transitions will be measured concurrently throughout the entire gradient. As the scheduling window narrows, the number of concurrently measured transitions decreases allowing for a higher duty cycle for each targeted transition which yields a higher number of points across a peak, which in turn leads to improved peak area measurement precision.

Figure 4.

Method development for custom polyamines assay. A) Comparison of concurrent transition count at different scheduling windows B) utilization of collision energy optimization for two analytes, spermidine (upper) and acetylspermine (lower).

In addition to retention time scheduling, Skyline was used for collision energy optimization for all of the compounds in this assay. A method was exported for CE optimization23, 26 with 2-volt increments (steps) for optimization, including five steps above and five below the starting voltage (11 distinct values, spanning a range of 20 volts). This workflow is enabled in the Settings->Transition Settings->Prediction tab, as shown in Figure S2. The collision energy for spermidine was optimal in the original method at 14 volts, which can be seen as the red bar in Figure 4B, the other collision energies tested from 4 to 24 volts resulted in the same (at 12 volts) or lower peak areas for the main spermidine transition. Conversely, for acetylspermine, the original collision energy (10 volts) was not the optimal energy, and the highest peak area is obtained at 16 volts, which would be the optimized CE used for this assay (Figure 4B). A unique feature of Skyline compared to other tools is the ability to perform highly multiplexed optimization of collision energy (CE) and other vendor-specific optimization parameters (such as declustering potential) during a chromatographic analysis. Most automated tools perform optimization during analyte infusion, which limits the number of compounds that can be performed simultaneously and typically involves user intervention. By performing CE optimization in a retention-time scheduled manner and on the chromatographic timescale, Skyline allows higher multiplexing of analytes for optimization and less user intervention.

Various mobile phase configurations were tested prior to selection of the final mobile phase for the polyamine assay. Included in the testing were 0.025% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) with 0.1% formic acid, 0.025% HFBA with 0.1% acetic acid, 0.0125% perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHA) with 0.1% formic acid and 0.0125% PFHA with 0.1% acetic acid. For a majority of the targeted compounds, the combination of 0.0125% PFHA and 0.1% acetic acid provided the largest peak area, as shown in Figure S3. Of the LC-MS/MS methods published for the analysis of underivatized polyamines, many utilize HFBA as an ion pairing reagent23, 24, 26, 27, however, the comparison of HFBA to PFHA revealed that PFHA provides not only better sensitivity but also better peak shape for many compounds.25 Assessing the peak intensity and peak shape of MTA under four different mobile phase conditions, acetic acid (0.1%) and HFBA (0.025%), formic acid (0.1%) and HFBA (0.025%), formic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%) and acetic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%), the best peak shape and intensity was obtained with the final mobile phase additive combination (Figure S3B-E). Better peak shape is obtained with acetic acid as seen in Figures S3B and S3E and the most intense peak is observed with PFHA combined with acetic acid.

The optimized assay was employed on a series of biological samples including cognitively normal human brains and mouse urine. Measured GABA is the most abundant compound detected in the human brain using this assay, followed by arginine at ~800 and ~400 nmol/g of human brain, respectively. Also detected in human brains were ornithine, SAM and SAH along with both N1- and N8-acetylspermidine and MTA. Acetylputrescine and spermine are not reported in human brains as values are below the LOD for this assay (see Table 1). In the tested mouse urine, the most abundant compounds quantified with the assay are arginine and ornithine at 4.36 and 3.63 μmol/mmol of creatinine, respectively. Concentrations of SAM and SAH are reported, with levels of SAM in urine higher than the reported levels of SAH. Whereas, in the human brain samples, the concentrations were comparable. Spermine levels were measured in urine along with several acetylated forms of the polyamines such as N1- and N8-acetylspermidine and acetylputrescine (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Brain and Urine Polyamine Concentrations

| Human Brain, Cognitive Normal (nmol/g) |

Mouse Urine, CVN (μmol/mmol creatinine) |

|

|---|---|---|

| GABA | 804 ± 432 | 1.4 ± 1.0 |

| AcPut | <LOD | 0.19 ± 0.08 |

| Orn | 33 ± 21 | 3.6 ± 2.3 |

| Arg | 401 ± 148 | 4.4 ± 3.3 |

| N1 AcSpd | 6.9 ± 5.0 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| N8 AcSpd | 8.6 ± 4.9 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Spm | <LOD | 1.0 ± 1.5 |

| MTA | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| SAH | 13.5 ± 4.4 | 2.4E-3 ± 4.4E-3 |

| SAM | 13.8 ± 8.8 | 2.2± 0.6 |

Average concentration of polyamines in cognitively normal human brain (n=19), and CVN mouse urine (n=13), measured using the custom polyamines assay and quantified with Skyline.

Skyline Supports Collection and Analysis of Positive/Negative Switching Ionization

For a specific example to evaluate the positive/negative switching features in Skyline a purine and pyrimidine analysis was chosen. Purines and pyrimidines serve several important biological roles, such as providing the structural backbone for nucleic acid synthesis (DNA, RNA), acting as precursors to enzyme co-factors (NAD, SAM, etc.), intermediates for energy metabolism (ATP), and a route to excretion of nitrogenous waste (uric acid, allantoin, etc.). They are at the intersection of a variety of metabolic pathways. However, this group of metabolites is structurally heterogeneous and contains compounds that preferentially ionize in either positive or negative mode. To accommodate for this, we used the SCIEX 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, which offers rapid positive/negative polarity switching and allows for the acquisition of SRM transitions (Q1/Q3) simultaneously under both ionization modes.44, 45 Given the short polarity switching time for this mass spectrometer, 112 transitions could be accommodated with a reasonable total cycle time of ~1.3 seconds, with all compounds in the group analyzed in a single LC-SRM-MS acquisition.

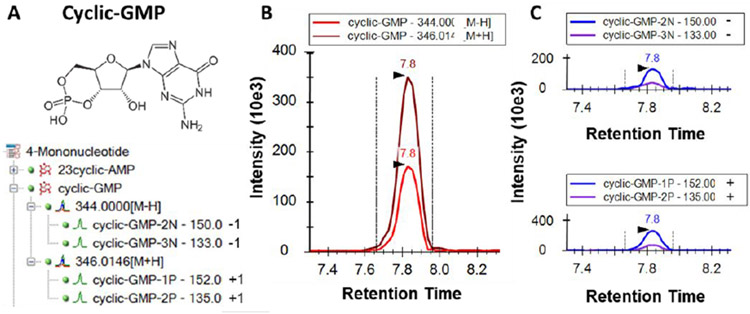

To evaluate the ability of Skyline to analyze data from positive and negative ionization modes in a single document, we generated a custom method analyzing purine/pyrimidine compounds on a SCIEX 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Figure 5). In Skyline, positively and negatively ionizing compounds can be presented in a combined fashion under the same compound name within the target tree, and the preferred ionization mode for this compound can be indicated by simply including “+1” for positive mode or “−1” for negative mode in the transition list at the precursor (Q1) and/or product ion (Q3) level. In addition, Skyline can indicate the charge state for the Q1 transition (precursor) more specifically, using IUPAC adduct nomenclature, either as [M+H] or as [M-H] as shown in Figure 5. Skyline imports the data from the LC-SRM-MS acquisitions to allow for simultaneous data processing for all compounds, irrespective of their individual ionization modes. Figure 5 shows the Skyline targets tree and representative ion traces for cyclic-GMP, acquired through positive/negative polarity switching of the source. Chromatograms for positive and negative transitions can be viewed individually, together or in a ‘split chromatogram’ view (see Figure 5C). By default, the ionization modes share the same integration time range.

Figure 5.

Targeted LC-SRM-MS analysis for purine and pyrimidine analysis using positive/negative switching. A) Molecular structure of cyclic-GMP and Skyline targets tree including molecule annotations and Q1/Q3 transitions, B) combined ion chromatogram showing data in negative ion mode [M-1] at m/z 344 and in positive ion mode [M+1] at m/z 346 and C) split graph representation for ion chromatograms in negative ion mode with Q1/Q3 transition pair 344/(150 and 133) (upper panel), and in positive ion mode with Q1/Q3 transition pair 346/(152 and 135) (lower panel).

Targeted Analysis of High-Resolution Metabolomics Data

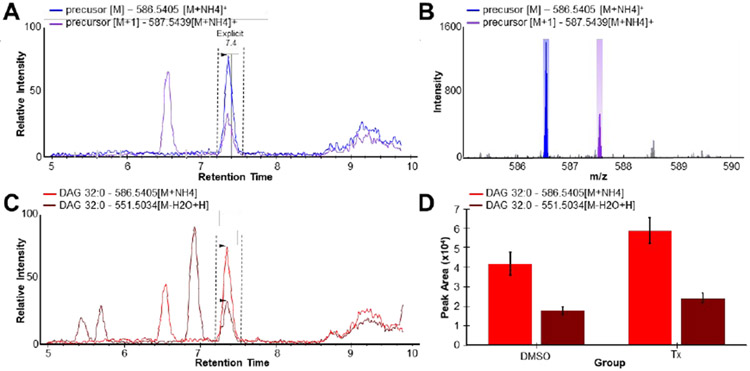

Skyline is not intended as a tool for traditional nontargeted metabolomics workflows. However, an important feature of the software is to perform hypothesis-driven targeted verification and visualization of high-resolution (HR) MS data collected for small molecules with nontargeted “discovery” acquisition methods. To demonstrate this, we utilized data from a previously published study that developed fatty acid synthase inhibitors in the context of anti-tumor activity in a model of HER2+ breast cancer.28 Alwarawrah et al. reported profound changes in cellular lipid profiles were observed using a QTOF MS in DDA mode, followed by nontargeted analysis with Progenesis QI software (Nonlinear Dynamics/Waters).30 It is worth noting that the Skyline analysis of lipidomics data from a Q Exactive (ThermoFisher Scientific) has previously been demonstrated, before Skyline was formally released for small molecules.32 Here, we focused on verification of two specific diacylglycerol species, DAG 30:0 and DAG 32:0, from (UPLC)/ESI/MS/MS analysis acquired on a G2 Synapt mass spectrometer (Waters), to demonstrate how the Skyline software can be used to verify accurate mass, isotope distribution, coelution of ionization adducts, and perform quantitative measurements. Though for the purposes of demonstration we only include a few lipid molecules, there is virtually no limit to the number of metabolites or metabolite features which could be included in such a list for verification, similar to what has previously been demonstrated for MS1 quantification of peptides.4 Figure S4 shows the transition list and full-scan transition settings used to perform this analysis in Skyline.

As an example, Figure 6A shows the M and M+1 isotope extracted ion chromatogram for the [M+NH4]+ adduct of DAG 32:0 from one of the cell line samples. Skyline enables lockmass correction of the high-resolution MS1 diacylglycerol precursor ion data, yielding −1 ppm relative mass accuracy for this measurement. By clicking on the extracted ion chromatogram, Skyline then accesses the mass spectrum at the clicked retention time from the raw data file, and displays the spectrum highlighting the extracted m/z ranges (Figure 6B). Additional confidence in the integration of the correct chromatogram peak in lipidomics analysis can be obtained by targeting multiple ionization adducts, similar to targeting multiple charge states for tryptic peptides in proteomics. For diacylglycerols the two most common ionization states are [M-H2O+H]+ and [M+NH4]+. Figure 6C shows that for DAG 32:0, both of these adducts have interference when totaled chromatograms for [M] and [M+1] are considered independently. Only the peak at 7.4 minutes, however, shows coelution of both ionization forms. Finally, the ability of Skyline to define sample groups (here DMSO and Tx) facilitates visual comparison of the average and standard deviation of treatment groups, for each ionization form (Figure 6D). Taken together, these features are key attributes for Skyline and its use as either the primary quantitative tool, or a secondary verification tool in high-resolution metabolomics analysis.

Figure 6.

Analysis of high-resolution metabolomics data in Skyline, in particular for a lipidomics analysis of diacylglycerol 32:0 (DAG 32:0) (A) Extracted ion chromatograms for the M and M+1 isotopes of DAG 32:0 [M+NH4]+ adduct (B) Mass spectrum zoomed to show 585 to 590 m/z viewed in Skyline of the DAG 32:0 [M+NH4]+ adduct ion (C) Extracted ion chromatogram totals of M and M+1 overlay of DAG 32:0 [M+NH4]+ and [M-H2O+H]+ adducts, and (D) Grouped comparison peak area view within Skyline of 5 replicates of each biological condition comparing means and standard deviations of control and FASN-inhibitor treated cells.

Conclusions

This study is the first to establish Skyline as a framework for comprehensive quantitative data processing not only for proteomics data but also now fully supporting the analysis of small molecule mass spectrometry data. We have demonstrated great versatility for small molecule workflows, and established Skyline as a tool expanding its capabilities for quantitative data processing into the metabolomics field. While all software tools have inherent advantages and disadvantages, we maintain that the primary advantage of Skyline over any other tool is the transparency with which data analysis and interpretation can be shared in the community, and in the translation of assays between instruments and laboratories without requiring separate analysis software. Skyline is freely available, actively supported, and the Skyline documents containing the workflows demonstrated here are available in Panorama (www.panoramaweb.org). All Panorama-enabled workflows for peptides, such as automated data import and quality control (“AutoQC”) have also been extended to small molecules.18, 19, 46

Though not explicitly demonstrated herein, the workflows described are also functional in Skyline for Agilent, Bruker, Shimadzu, and Thermo mass spectrometers, in addition to Sciex and Waters used in this report. Additionally, Skyline already supports a number of other workflows utilized in small molecule analysis, including parallel reaction monitoring (PRM), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and single-point external calibration. Future work will also implement workflows in Skyline to support fragmentation libraries of small molecules, such as Metlin (http://metlin.scripps.edu/)47, 48, MassBank49, the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, http://www.hmdb.ca/)50, 51 and the National Institute of Standards and Technology Database (NIST https://chemdata.nist.gov/); similar workflows are already available for proteomics experiments.3, 4 Though expansion of support for GC-MS and all types of ion mobility small molecule data are also ongoing, we would caution that no single tool will be best for all workflows. Especially in the case of latest-generation or vendor-specific workflows, Skyline may lag behind commercial software for a time until support can be implemented. Skyline external tools52 will also allow for linking small molecule quantitative data sets with other data processing pipelines.

In summary, Skyline has become a versatile and powerful open source software solution for quantitative mass spectrometry data workflows, and can now support both proteomics and metabolomics workflows in a vendor neutral environment. Combined with the features of Panorama to easily share methods and datasets, Skyline is positioned to drastically improve the transparency and open translation of metabolomics data and methods between laboratories. We believe Skyline has the ability to gain broad use and acceptance in the small molecule / metabolomics field as it has in quantitative proteomics.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Ion transitions, collision energy, cell exit potential, declustering potential and entrance potential for the purine and pyrimidines LC-MS/MS panel.

Table S2. Ion transitions, collision energy values, retention times and internal standards for targeted compounds in the polyamines custom assay.

Figure S1. Screenshot of the small-molecule filter tab in Skyline, allowing the user to define the precursor and fragment ion adducts desired for analysis. Additionally, the user can utilize the ‘ion types’ field to define the analysis of a precursor (‘p’) or fragment (‘f’) in a document-wide fashion.

Figure S2. Collision energy optimization enabled via Settings->Transition Settings->Prediction tab.

Figure S3. A) Peak area of targeted compounds with different mobile phase additives. Peak shape and intensity for MTA elution with B) acetic acid (0.1%) and HFBA (0.025%) C), formic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%), D) and acetic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%).

Figures S4. Examples how to set up the transition list (A) and the Full Scan parameter settings (B) for the Skyline analysis of high-resolution metabolomics data. Specifically, in this case the transition list allows for analysis of two diacylglycerol lipids, each with two adduct ionization forms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu), and contributed by the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium (ADMC, https://sites.duke.edu/adnimetab/). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this article. Researchers can apply for ADNI data at http://adni.loni.usc.edu/data-samples/access-data/. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded in part by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012).

ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California.

ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Metabolomics Consortium (National Institute on Aging R01AG046171, RF1AG051550 and 3U01AG024904-09S4).]

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health: RF1 AG057358 (MPI: Lithgow, Andersen - BS), R56 AG057895 (MPI: Colton, Thompson), R01 AG057895 (MPI: Colton, Thompson), and P41 GM103493, R01 GM103551, P30 AG013280, and R56 AG063885 (to MJM). NB was supported by a NIH fellowship grant (T32 AG000266, PI: Campisi).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED INFORMATION

Supporting Information. Supporting information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website, compiled as the document Skyline_Small_Molecules_Supplement.pdf.

Additional Information. A beginner tutorial called “Getting Started with Skyline for Small Molecules” is included in the supplementary information. This tutorial, as well as additional tutorials for detailed features of Skyline analysis for small molecules, are available at https://skyline.ms/tutorials.url. Also, a short webinar is available at the following link: https://skyline.ms/tutorial_small_molecule.url.

Data Accession

All Skyline files are located on the public Panorama Share: https://panoramaweb.org/SkylineForSmallMolecules.url

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbatiello SE; Mani DR; Schilling B; Maclean B; Zimmerman LJ; Feng X; Cusack MP; Sedransk N; Hall SC; Addona T; Allen S; Dodder NG; Ghosh M; Held JM; Hedrick V; Inerowicz HD; Jackson A; Keshishian H; Kim JW; Lyssand JS; Riley CP; Rudnick P; Sadowski P; Shaddox K; Smith D; Tomazela D; Wahlander A; Waldemarson S; Whitwell CA; You J; Zhang S; Kinsinger CR; Mesri M; Rodriguez H; Borchers CH; Buck C; Fisher SJ; Gibson BW; Liebler D; Maccoss M; Neubert TA; Paulovich A; Regnier F; Skates SJ; Tempst P; Wang M; Carr SA, Design, implementation and multisite evaluation of a system suitability protocol for the quantitative assessment of instrument performance in liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring-MS (LC-MRM-MS). Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2013, 12 (9), 2623–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbatiello SE; Schilling B; Mani DR; Zimmerman LJ; Hall SC; MacLean B; Albertolle M; Allen S; Burgess M; Cusack MP; Gosh M; Hedrick V; Held JM; Inerowicz HD; Jackson A; Keshishian H; Kinsinger CR; Lyssand J; Makowski L; Mesri M; Rodriguez H; Rudnick P; Sadowski P; Sedransk N; Shaddox K; Skates SJ; Kuhn E; Smith D; Whiteaker JR; Whitwell C; Zhang S; Borchers CH; Fisher SJ; Gibson BW; Liebler DC; MacCoss MJ; Neubert TA; Paulovich AG; Regnier FE; Tempst P; Carr SA, Large-scale interlaboratory study to develop, analytically validate and apply highly multiplexed, quantitative peptide assays to measure cancer-relevant proteins in plasma. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2015, 14 (9), 2357–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLean B; Tomazela DM; Shulman N; Chambers M; Finney GL; Frewen B; Kern R; Tabb DL; Liebler DC; MacCoss MJ, Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 2010, 26 (7), 966–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schilling B; Rardin MJ; MacLean BX; Zawadzka AM; Frewen BE; Cusack MP; Sorensen DJ; Bereman MS; Jing E; Wu CC; Verdin E; Kahn CR; Maccoss MJ; Gibson BW, Platform-independent and label-free quantitation of proteomic data using MSI extracted ion chromatograms in skyline: application to protein acetylation and phosphorylation. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2012, 11 (5), 202–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rardin MJ, Rapid Assessment of Contaminants and Interferences in Mass Spectrometry Data Using Skyline. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2018, 29 (6), 1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schilling B; MacLean B; Held JM; Sahu AK; Rardin MJ; Sorensen DJ; Peters T; Wolfe AJ; Hunter CL; MacCoss MJ; Gibson BW, Multiplexed, scheduled, high-resolution parallel reaction monitoring on a full scan QqTOF instrument with integrated data-dependent and targeted mass spectrometric workflows. Analytical chemistry 2015, 87 (20), 10222–10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim HW; Kang SG; Ryu JK; Schilling B; Fei M; Lee IS; Kehasse A; Shirakawa K; Yokoyama M; Schnolzer M; Kasler HG; Kwon HS; Gibson BW; Sato H; Akassoglou K; Xiao C; Littman DR; Ott M; Verdin E, SIRT1 deacetylates RORγt and enhances Th17 cell generation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2015, 212 (5), 607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro P; Kuharev J; Gillet LC; Bernhardt OM; MacLean B; Rost HL; Tate SA; Tsou CC; Reiter L; Distler U; Rosenberger G; Perez-Riverol Y; Nesvizhskii AI; Aebersold R; Tenzer S, A multicenter study benchmarks software tools for label-free proteome quantification. Nature biotechnology 2016, 34 (11), 1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egertson JD; MacLean B; Johnson R; Xuan Y; MacCoss MJ, Multiplexed peptide analysis using data-independent acquisition and Skyline. Nature protocols 2015, 10 (6), 887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pino LK; Searle BC; Bollinger JG; Nunn B; MacLean B; MacCoss MJ, The Skyline ecosystem: Informatics for quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics. Mass spectrometry reviews 2017, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLean B; Tomazela DM; Abbatiello SE; Zhang S; Whiteaker JR; Paulovich AG; Carr SA; MacCoss MJ, Effect of collision energy optimization on the measurement of peptides by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry 2010, 82 (24), 10116–10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CA; Want EJ; O'Maille G; Abagyan R; Siuzdak G, XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Analytical chemistry 2006, 78 (3), 779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pluskal T; Castillo S; Villar-Briones A; OreŠič M, MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC bioinformatics 2010, 11 (1), 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsugawa H; Cajka T; Kind T; Ma Y; Higgins B; Ikeda K; Kanazawa M; VanderGheynst J; Fiehn O; Arita M, MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nature methods 2015, 12 (6), 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domingo-Almenara X; Montenegro-Burke JR; Ivanisevic J; Thomas A; Sidibe J; Teav T; Guijas C; Aisporna AE; Rinehart D; Hoang L; Nordstrom A; Gomez-Romero M; Whiley L; Lewis MR; Nicholson JK; Benton HP; Siuzdak G, XCMS-MRM and METLIN-MRM: a cloud library and public resource for targeted analysis of small molecules. Nat Methods 2018, 15 (9), 681–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsugawa H; Kanazawa M; Ogiwara A; Arita M, MRMPROBS suite for metabolomics using large-scale MRM assays. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (16), 2379–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amodei D; Egertson J; MacLean BX; Johnson R; Merrihew GE; Keller A; Marsh D; Vitek O; Mallick P; MacCoss MJ, Improving Precursor Selectivity in Data-Independent Acquisition Using Overlapping Windows. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2019, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma V; Eckels J; Schilling B; Ludwig C; Jaffe JD; MacCoss MJ; MacLean B, Panorama Public: A public repository for quantitative data sets processed in Skyline. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2018, 17 (6), 1239–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma V; Eckels J; Taylor GK; Shulman NJ; Stergachis AB; Joyner SA; Yan P; Whiteaker JR; Halusa GN; Schilling B; Gibson BW; Colangelo CM; Paulovich AG; Carr SA; Jaffe JD; MacCoss MJ; MacLean B, Panorama: a targeted proteomics knowledge base. Journal of proteome research 2014, 13 (9), 4205–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St John-Williams L; Blach C; Toledo JB; Rotroff DM; Kim S; Klavins K; Baillie R; Han X; Mahmoudiandehkordi S; Jack J; Massaro TJ; Lucas JE; Louie G; Motsinger-Reif AA; Risacher SL; Saykin AJ; Kastenmuller G; Arnold M; Koal T; Moseley MA; Mangravite LM; Peters MA; Tenenbaum JD; Thompson JW; Kaddurah-Daouk R, Targeted metabolomics and medication classification data from participants in the ADNI1 cohort. Scientific data 2017, 4, 170140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toledo JB; Arnold M; Kastenmuller G; Chang R; Baillie RA; Han X; Thambisetty M; Tenenbaum JD; Suhre K; Thompson JW; John-Williams LS; MahmoudianDehkordi S; Rotroff DM; Jack JR; Motsinger-Reif A; Risacher SL; Blach C; Lucas JE; Massaro T; Louie G; Zhu H; Dallmann G; Klavins K; Koal T; Kim S; Nho K; Shen L; Casanova R; Varma S; Legido-Quigley C; Moseley MA; Zhu K; Henri on MYR; van der Lee SJ; Harms AC; Demirkan A; Hankemeier T; van Duijn CM; Trojanowski JQ; Shaw LM; Saykin AJ; Weiner MW; Doraiswamy PM; Kaddurah-Daouk R, Metabolic network failures in Alzheimer's disease: A biochemical road map. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2017, 13 (9), 965–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Hadithi NN; Saad B, Determination of underivatized polyamines: a review of analytical methods and applications. Analytical Letters 2011, 44 (13), 2245–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Häkkinen MR; Roine A; Auriola S; Tuokko A; Veskimäe E; Keinänen TA; Lehtimäki T; Oksala N; Vepsäläinen J, Analysis of free, mono-and diacetylated polyamines from human urine by LC–MS/MS. Journal of Chromatography B 2013, 941, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu R; Li Q; Ma R; Lin X; Xu H; Bi K, Determination of polyamine metabolome in plasma and urine by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method: Application to identify potential markers for human hepatic cancer. Analytica chimica acta 2013, 791, 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu C; Liu R; Xie C; Zhang Q; Yin Y; Bi K; Li Q, Quantification of free polyamines and their metabolites in biofluids and liver tissue by UHPLC-MS/MS: application to identify the potential biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2015, 407 (22), 6891–6897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima T; Katsumata K; Kuwabara H; Soya R; Enomoto M; Ishizaki T; Tsuchida A; Mori M; Hiwatari K; Soga T; Tomita M; Sugimoto M, Urinary polyamine biomarker panels with machine-learning differentiated colorectal cancers, benign disease, and healthy controls. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19 (3), 756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens AP; Dettmer K; Kirovski G; Samejima K; Hellerbrand C; Bosserhoff AK; Oefner PJ, Quantification of intermediates of the methionine and polyamine metabolism by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in cultured tumor cells and liver biopsies. Journal of chromatography A 2010, 1217 (19), 3282–3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alwarawrah M; Hussain F; Huang J, Alteration of lipid membrane structure and dynamics by diacylglycerols with unsaturated chains. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2016, 1858 (2), 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcock DM; Lewis MR; Van Nostrand WE; Davis J; Previti ML; Gharkholonarehe N; Vitek MP; Colton CA, Progression of amyloid pathology to Alzheimer's disease pathology in an amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse model by removal of nitric oxide synthase 2. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28 (7), 1537–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alwarawrah Y; Hughes P; Loiselle D; Carlson DA; Darr DB; Jordan JL; Xiong J; Hunter LM; Dubois LG; Thompson JW; Kulkarni MM; Ratcliff AN; Kwiek JJ; Haystead TA, Fasnall, a selective FASN inhibitor, shows potent anti-tumor activity in the MMTV-Neu model of HER2+ breast cancer. Cell chemical biology 2016, 23 (6), 678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chavez JD; Eng JK; Schweppe DK; Cilia M; Rivera K; Zhong X; Wu X; Allen T; Khurgel M; Kumar A; Lampropoulos A; Larsson M; Maity S; Morozov Y; Pathmasiri W; Perez-Neut M; Pineyro-Ruiz C; Polina E; Post S; Rider M; Tokmina-Roszyk D; Tyson K; Vieira D; Sant'Ana P; James BE, A general method for targeted quantitative cross-linking mass spectrometry. PLoS One 2016, 11 (12), e0167547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng B; Ahrends R, Adaptation of skyline for targeted lipidomics. Journal of proteome research 2015, 15 (1), 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang X; Keenan MM; Wu J; Lin C-A; Dubois L; Thompson JW; Freedland SJ; Murphy SK; Chi J-T, Comprehensive profiling of amino acid response uncovers unique methionine-deprived response dependent on intact creatine biosynthesis. PLoS genetics 2015, 11 (4), e1005158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimbung S; Chang C.-y.; Bendahl, P-O; Dubois L; Thompson JW; McDonnell DP; Borgquist S, Impact of 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) and 27-hydroxycholesterol in breast cancer. Endocrine-related cancer 2017, 24 (7), 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourgeois JS; Zhou D; Thurston TL; Gilchrist JJ; Ko DC, Methylthioadenosine suppresses Salmonella virulence. Infection and immunity 2018, 86 (9), e00429–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson CM; Shulman NJ; MacLean B; MacCoss MJ; Hoofnagle AN, Skyline Performs as Well as Vendor Software in the Quantitative Analysis of Serum 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D and Vitamin D Binding Globulin. Clinical Chemistry 2018, 64 (2), 408–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan X; Nasaruddin MB; Elliott CT; McGuinness B; Passmore AP; Kehoe PG; Hölscher C; McClean PL; Graham SF; Green BD, Alzheimer's disease–like pathology has transient effects on the brain and blood metabolome. Neurobiology of aging 2016, 38, 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dammeier S; Martus P; Klose F; Seid M; Bosch D; Janina DA; Ziemssen F; Dimopoulos S; Ueffing M, Combined Targeted Analysis of Metabolites and Proteins in Tear Fluid With Regard to Clinical Applications. Translational vision science & technology 2018, 7 (6), 22–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison A; Dubois LG; St John-Williams L; Moseley MA; Hardison RL; Heimlich DR; Stoddard A; Kerschner JE; Justice SS; Thompson JW; Mason KM, Comprehensive proteomic and metabolomic signatures of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced acute otitis media reveal bacterial aerobic respiration in an immunosuppressed environment. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2016, 15 (3), 1117–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerner EW; Meyskens FL Jr, Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nature Reviews Cancer 2004, 4 (10), 781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minois N; Carmona-Gutierrez D; Madeo F, Polyamines in aging and disease. Aging 2011, 3 (8), 716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moinard C; Cynober L; de Bandt J-P, Polyamines: metabolism and implications in human diseases. Clinical Nutrition 2005, 24 (2), 184–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park MH; Igarashi K, Polyamines and their metabolites as diagnostic markers of human diseases. Biomolecules & therapeutics 2013, 21 (1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breitkopf SB; Ricoult SJ; Yuan M; Xu Y; Peake DA; Manning BD; Asara JM, A relative quantitative positive/negative ion switching method for untargeted lipidomics via high resolution LC-MS/MS from any biological source. Metabolomics 2017, 13 (3), 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan M; Breitkopf SB; Yang X; Asara JM, A positive/negative ion–switching, targeted mass spectrometry–based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nature protocols 2012, 7 (5), 872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bereman MS; Beri J; Sharma V; Nathe C; Eckels J; MacLean B; MacCoss MJ, An Automated Pipeline to Monitor System Performance in Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Proteomic Experiments. J Proteome Res 2016, 15 (12), 4763–4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guijas C; Montenegro-Burke JR; Domingo-Almenara X; Palermo A; Warth B; Hermann G; Koellensperger G; Huan T; Uritboonthai W; Aisporna AE; Wolan DW; Spilker ME; Benton HP; Siuzdak G, METLIN: a technology platform for identifying knowns and unknowns. Analytical chemistry 2018, 90 (5), 3156–3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith CA; O'Maille G; Want EJ; Qin C; Trauger SA; Brandon TR; Custodio DE; Abagyan R; Siuzdak G, METLIN: a metabolite mass spectral database. Therapeutic drug monitoring 2005, 27 (6), 747–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horai H; Arita M; Kanaya S; Nihei Y; Ikeda T; Suwa K; Ojima Y; Tanaka K; Tanaka S; Aoshima K; Oda Y; Kakazu Y; Kusano M; Tohge T; Matsuda F; Sawada Y; Hirai MY; Nakanishi H; Ikeda K; Akimoto N; Maoka T; Takahashi H; Ara T; Sakurai N; Suzuki H; Shibata D; Neumann S; Iida T; Tanaka K; Funatsu K; Matsuura F; Soga T; Taguchi R; Saito K; Nishioka T, MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. Journal of mass spectrometry 2010, 45 (7), 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wishart DS; Feunang YD; Marcu A; Guo AC; Liang K; Vazquez-Fresno R; Sajed T; Johnson D; Li C; Karu N; Sayeeda Z; Lo E; Assempour N; Berjanskii M; Singhal S; Arndt D; Liang Y; Badran H; Grant J; Serra-Cayuela A; Liu Y; Mandal R; Neveu V; Pon A; Knox C; Wilson M; Manach C; Scalbert A, HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic acids research 2017, 46 (D1), D608–D617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wishart DS; Knox C; Guo AC; Eisner R; Young N; Gautam B; Hau DD; Psychogios N; Dong E; Bouatra S, HMDB: a knowledgebase for the human metabolome. Nucleic acids research 2008, 37 (suppl_1), D603–D610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broudy D; Killeen T; Choi M; Shulman N; Mani DR; Abbatiello SE; Mani D; Ahmad R; Sahu AK; Schilling B; Tamura K; Boss Y; Sharma V; Gibson BW; Carr SA; Vitek O; MacCoss MJ; MacLean B, A framework for installable external tools in Skyline. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (17), 2521–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Ion transitions, collision energy, cell exit potential, declustering potential and entrance potential for the purine and pyrimidines LC-MS/MS panel.

Table S2. Ion transitions, collision energy values, retention times and internal standards for targeted compounds in the polyamines custom assay.

Figure S1. Screenshot of the small-molecule filter tab in Skyline, allowing the user to define the precursor and fragment ion adducts desired for analysis. Additionally, the user can utilize the ‘ion types’ field to define the analysis of a precursor (‘p’) or fragment (‘f’) in a document-wide fashion.

Figure S2. Collision energy optimization enabled via Settings->Transition Settings->Prediction tab.

Figure S3. A) Peak area of targeted compounds with different mobile phase additives. Peak shape and intensity for MTA elution with B) acetic acid (0.1%) and HFBA (0.025%) C), formic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%), D) and acetic acid (0.1%) and PFHA (0.0125%).

Figures S4. Examples how to set up the transition list (A) and the Full Scan parameter settings (B) for the Skyline analysis of high-resolution metabolomics data. Specifically, in this case the transition list allows for analysis of two diacylglycerol lipids, each with two adduct ionization forms.