Abstract

Background:

The continued toll of opioid-related overdoses has motivated efforts to expand availability of naloxone to persons at high risk of overdose, with 2016 federal guidance encouraging clinicians to co-prescribe naloxone to patients with increased overdose risk. Some states have pursued analogous or stricter legal requirements that could more heavily influence prescriber behavior.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic legal review of state laws that mandate or recommend that healthcare providers prescribe naloxone to patients with indicators for opioid overdose risk. We coded relevant statutes and regulations for: applicable populations, patient criteria, educational requirements, and exemptions.

Results:

As of September 2019, 17 states had enacted naloxone co-prescribing laws, the earliest of which was implemented by Louisiana in January 2016. If patient overdose risk criteria are met, over half of these states mandate that providers prescribe naloxone (7 states, 41.1 %) or offer a naloxone prescription (2 states, 11.8 %); the remainder encourage prescribers to consider prescribing naloxone (8 states). Most states (58.8 %) define patient overdose risk based on opioid dosages prescribed, although the threshold varies substantially; other common overdose risk criteria include concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions and patient history of substance use disorder or mental illness.

Conclusions:

A growing minority of states has adopted a naloxone prescribing law, although these policies remain less prevalent than other naloxone access laws. By targeting higher-risk patients during clinical encounters, naloxone prescribing requirements could increase naloxone prescribed, destigmatize naloxone use, and reduce overdose harms. Further investigation into policy effectiveness, unintended consequences, and appropriate parameters is warranted.

Keywords: Naloxone, Opioid policy, Co-prescription, Overdose, Harm reduction

1. Introduction

As fatal opioid overdose rates have skyrocketed over the past decade, there has been rapid growth in state laws that expand naloxone access and use in the community setting (Davis and Carr, 2017). Pharmacists can now dispense naloxone through non-patient-specific prescription models or prescriptive authority in all states; these laws have shown potential to increase distribution of naloxone (Abouk et al., 2019; Gertner et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018) and reduce opioid-related overdose mortality (Abouk et al., 2019; McClellan et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019). However, a wealth of studies suggest that naloxone laws that intervene through the pharmacy dispensation channel may be inadequate to promote sufficient naloxone access in many states, due to concerns over dispensing logistics, inadequate knowledge about the legislation, discomfort among pharmacists about dispensing naloxone through non-patient-specific prescription models, reimbursement issues, and low demand among pharmacy patrons (Evoy et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2017; Green et al., 2017; Meyerson et al., 2018; Puzantian and Gasper, 2018; Thompson et al., 2019; Thornton et al., 2017; Zaller et al., 2013).

As a complementary effort to encourage greater naloxone access, the March 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommended the co-prescription of naloxone for patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, prescribed opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) or more, or with concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid use (CDC, 2016). Other federal agencies and national medical organizations, like the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office and the American Medical Association, have also strongly supported this practice (Adams, 2018; AMA, 2017; SAMHSA, 2018).

More recently, numerous states have adopted some form of naloxone prescribing requirement or recommendation (“naloxone prescription laws”). Naloxone prescription laws follow a trend of states adapting CDC Guidelines into law, as has occurred with opioid prescription days’ supply and dosage limitations (Davis et al., 2019). Although evidence suggests that certain CDC guidelines modestly change opioid prescribing behavior (Bohnert et al., 2018), they are not legally binding. State naloxone prescription laws have the potential to more dramatically affect prescribers, in part due to higher salience to providers who may be legally obligated to comply with their provisions and who may exhibit greater compliance with regulations administered by professional licensing bodies. Because the laws encourage intervention among potentially higher-risk patients when engaging with a trusted medical professional, naloxone prescription laws could increase naloxone prescribed and dispensed, destigmatize naloxone use, offer information about insurance coverage, and reduce overdose harms more effectively than pharmacy naloxone access laws, at least among certain populations.

Indeed, early indications suggest that two of the first naloxone prescription laws, in Virginia and Vermont, were associated with dramatic increases in naloxone prescriptions (Sohn et al., 2019), although these effects may have been short-lived. As more states consider enacting these laws, it will be critical to understand variation across states in the prescriber and patient populations to which they apply. To better inform the current policy landscape and ongoing evaluation efforts, we provide the first systematic review of these rapidly emerging laws to elucidate state practices, facilitate policy evaluation, and prompt consideration of best practices.

2. Methods

Two trained legal researchers (R.L.H and S.C.) systematically reviewed the Westlaw and Nexis Uni databases for all statutes and regulations in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia that require or recommend naloxone prescribing under specified circumstances. Each state’s statutes and regulations were independently searched for laws enacted by September 30, 2019 that included the terms (“antagonist! or naloxone or reversal”) and (“co-prescr! or co-prescri! or benzo! or prescr!”). We also conducted internet searches for these terms, and we reviewed state legislative and regulatory websites for relevant documentation.

Each legal researcher made a determination as to whether each identified law met the pre-specified study inclusion criteria. We excluded laws that more generally relate to naloxone access—such as laws relating to distribution and possession by laypeople, third party or standing order authorizations, laws generally encouraging naloxone prescribing (absent specific patient risk factors), and laws providing immunity for naloxone prescribers, dispensers, administrators—as these have been characterized elsewhere (Davis and Carr, 2017). We identified features that emerged in the laws, including: applicable prescriber and patient populations, nature of the co-prescribing requirement or recommendation, antagonist specified, patient triggering criteria (i.e., opioid prescribing characteristics, polypharmacy, patient medical history or condition), exemptions, and prescriber penalty for violation. Each researcher then coded these features for each law included. We collaboratively reconciled minor differences in laws identified and features characterized.

3. Results

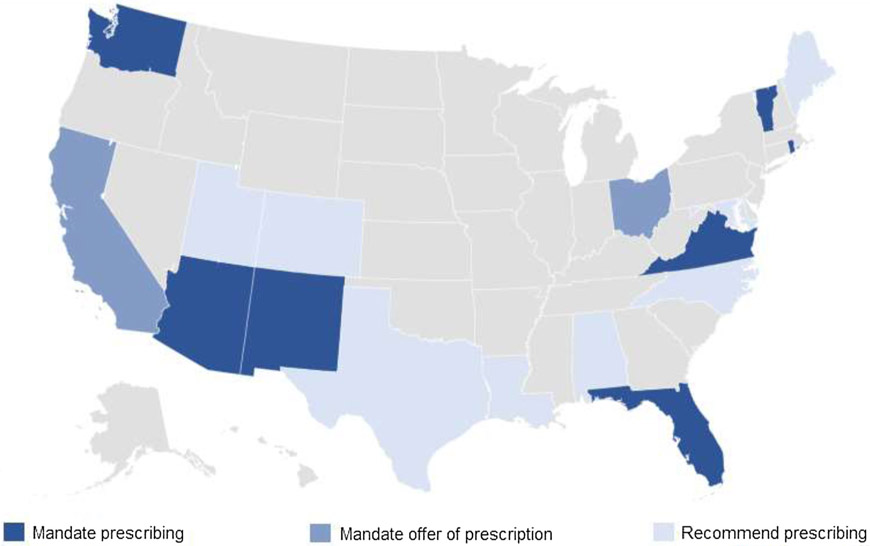

As of September 30, 2019, 17 states had enacted laws requiring or recommending naloxone be prescribed, the first of which was Louisiana in January 2016 (Fig. 1). Seven states (AZ, FL, NM, RI, VA, VT, WA) mandate that providers prescribe naloxone to patients meeting specified criteria for opioid overdose risk. Two states (CA, OH) require providers to offer a prescription for naloxone to patients meeting overdose risk criteria. Eight additional states (AL, CO, LA, ME, MD, NC, TX, UT) encourage providers to consider prescribing naloxone to certain patients. In contrast to the regional concentration documented for laws limiting opioid prescriptions for acute pain (Davis et al., 2019), naloxone prescription laws exhibit substantial geographic variation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

State Naloxone Prescribing Requirements and Recommendations, September 30, 2019.

Most naloxone prescription laws apply to all prescribing health professionals, although some specifically apply to prescribers of controlled substances (FL, UT), prescribers of opioid analgesics (NM), specific types of clinicians (OH, VA, WA), or clinicians in select practice settings (two NM laws). Most laws also exclusively name naloxone as the antagonist to be co-prescribed, although several (AZ, CA, FL, NM, MD) referred more broadly to opioid antagonists “approved by the Food and Drug Administration”.

3.1. Patients warranting a naloxone prescription

As shown in Table 1, ten states (58.8 %) define patient overdose risk warranting a naloxone prescription based on opioid dosages prescribed, although the threshold varies from 50 to 120 MMEs per day. Only four states (26.7 %) follow the CDC-recommended 50 MME threshold. Other common overdose risk criteria include patient concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions (n = 9), history of substance use disorder or opioid use disorder (n = 12), history of overdose (n = 7), or history of mental illness (n = 5). Less common overdose risk criteria include patient respiratory disease (n = 3), opioid tolerance or chronic pain (n = 3), and risk of returning to a high opioid dose to which patient is no longer tolerant (n = 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of State Laws Requiring or Recommending Naloxone Prescriptions.

| Law Type | Effective Date | Applicable Prescribers | Applicable Patients | Patient Criteriaa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Citation | Opioid Supply/ Dosage |

Polypharmacy | History or Condition | |||

| Mandate prescribing | |||||||

| AZ | ARS § 32-3248.01 | 4/26/2018 | All | All | > 90 MME/day | - | - |

| FL | FL Stat § 456.44 | 7/1/2018 | Schedule II prescribers | All | - | - | ISS ≥ 9 in pain treatment |

| NM | NMSA § 24-2D-1 | 3/28/2019 | OA prescribers | All | ≥ 5-day supply | - | - |

| NM | NMSA § 24-23-3 | 6/16/2017 | OTP | OTP | - | - | OUD |

| NM | NMSA § 33-2-51 | 6/16/2017 | Corrections dept. | Former inmates | - | - | OUD |

| RI | 216-RICR-20-20-4 | 7/2/2018 | All | All | ≥ 50 MME/day | BZD & opioid | OD, OUD |

| VT | Vt Code R 2 3 7 | 7/1/2017 | All | All | ≥ 90 MME/day | BZD & opioid | OD, SUD |

| VA | 18 Va Admin Code §§ 85-21-40,70; 60-21-103 | 3/15/2017 | All (including dentists) | All | >120 MME/day | BZD & opioid | - |

| WA | WAC §§ 246-840-4980, 246-853-785, 246-922-785, 246-919-980, 246-817-977, 246-854-365, 246-918-930 | 11/1/2018 & after | Physicians, APNPs, PAs, Dentists, Podiatrists | All | ≥ 50 MME/day | BZD & opioid | SUD, MI, OUD, illicit drug use |

| Mandate offer | |||||||

| CA | CA Bus & Prof Code §§740-742 | 1/1/2019 | All | All | ≥ 90 MME/day | BZD & opioid | OD, OUD, at-risk for returning to non-tolerant high opioid dose |

| OH | OAC §§ 4731-11-14, 4723-9-10 | 12/23/2018 | Physicians, APNPs | All | ≥ 80 MME/day | Opioid &: BZD/sedative,carisprodal, tramadol, gabapentin | OD, SUD |

| Recommend | |||||||

| AL | Ala Admin Code r. 540-X-4-.09 | 9/2/2018 | All | All | - | - | Opioid treatment |

| CO | 7 CCR 1101-3 Rule 17, Ex 7, 9 | 11/30/2017 | All | Worker’s Compensationc | - | Concurrent opioids | Chronic pain, MI, SUD, |

| LA | La Admin Code tit. 48 § 3901 | 1/20/2016 | All | All | > 14-day supply | - | - |

| MEb | 02-396 CMR Ch 21 §§2,3 | 6/30/2018 | All | All | - | Opioid &: BZD, tobacco, other opioids | SUD, MI, RD, falls, physical or sexual abuse, “doctor shopping” for opioids |

| MEb | Exec. Order 2 | 2/6/2019 | All | All | >100 MME/day | Dangerous combinations | - |

| MD | COMAR § 10.13.03 | 6/17/2019 | All | All | - | BZD & opioid | OUD, opioid treatment |

| NC | 11 NCAC § 23 M.0301 | 5/1/2018 | All | Worker’s Compensationc | > 50 MME/day | BZD & CS | OD, SUD, MI, RD |

| TX | 22 Tex Admin Code § 170.6 | 7/6/2018 | All | All | - | Concurrent opioids | OD, OUD, SUD, opioid or addiction treatment, recent incarceration release, resumed opioid therapy after interruption |

| UT | UT Admin Code r. R384-210 | 6/7/2018 | CS prescribers | All | ≥ 50 MME/day | BZD & opioid | OD, SUD, MI, RD |

Abbreviations: APNP, advanced practice nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; CS, controlled substance; OA, opioid analgesic; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; BZD, benzodiazepine; OD, overdose; OTP, federally certified opioid treatment program; OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder; MI, mental illness; RD, respiratory disease; ISS, injury severity score.

Patients need only to satisfy one, rather than all, of these criteria for a given law’s provisions to apply.

Maine has another law, 10-144 CMR Ch. 101 §80.07-12 (effective 9/1/2017) requiring MaineCare prescribers to consider offering naloxone if medically indicated and if opioid therapy is continued beyond 3 months to members with current use of benzodiazepines, a mental health or substance use disorder, or a medical condition that increases sensitivity.

Worker’s compensation indicates that these laws apply only when an employee files a worker’s compensation claim and receives medical expense benefits for harm incurred while performing work-related duties.

Naloxone prescription laws generally apply to all patients meeting at least one of the aforementioned criteria, with select exceptions. California and Ohio specify exemptions from the mandated prescription offer for terminally ill patients and opioid administration in an inpatient setting. Colorado and North Carolina established the guidelines only for the workers’ compensation context. New Mexico’s earlier laws applied only to patients treated in opioid treatment programs or to inmates discharged from corrections facilities with a diagnosis of OUD.

3.2. Penalties and education requirements

The mandated naloxone prescription laws do not explicitly set forth penalties for prescriber violation, although the prescriber can or, in California, must, be referred to the appropriate licensing board for potential imposition of administrative sanctions deemed appropriate by the board. Seven states (CA, CO, ME, MD, NM, UT, WA) require or encourage the prescribing healthcare professional to provide patient education regarding opioid overdose prevention and the use of naloxone.

4. Discussion

There is a growing trend towards state enactment of naloxone prescription laws, with 17 states having implemented laws since January 2016. However, the patient criteria that trigger naloxone prescribing, and whether prescribing is required or merely recommended, differ among these laws in ways that may meaningfully influence policy impact. As more states consider these laws, it will be important to see whether laws begin to converge on a consistent determination of patient overdose risk or whether they continue to exhibit substantial variation. Furthermore, it will be critical to evaluate whether these laws are adequately targeting those individuals who could benefit from naloxone prescribing and whether they are promoting equitable and effective naloxone access.

4.1. Potential benefits and limitations

While CDC relied upon evidence—including patient risk factors for overdose—in forming its Guideline, it recently clarified that the recommendations were not meant to be bright-line rules or to induce dramatic reductions in prescription opioid analgesic supply. Rather, CDC encouraged individualized assessments and determinations be made based upon patient factors when prescribing opioid analgesics (Dowell et al., 2019). This particular guideline regarding naloxone prescribing raises less cause for concern than others, given that naloxone is a harm reduction medication without serious adverse side effects. Nonetheless, many states go beyond what the CDC recommended to include patient risks factors such as prior opioid therapy, history of mental illness, or history of respiratory disease.

While there is strong evidence that naloxone administration is effective at reversing overdoses (Giglio et al., 2015), one may question whether naloxone prescription laws would have limited impact given the pre-existing naloxone policy environment in states that have implemented these laws. All 17 states that passed naloxone prescription requirements or recommendations had already implemented innovative pharmacy-based naloxone distribution mechanisms (Davis and Carr, 2017) and expanded naloxone administration authority to non-paramedic emergency medical personnel (Kinsman and Robinson, 2018). Furthermore, many of the states that have adopted naloxone prescription requirements (e.g., RI, NM, WA) are well-served by community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs (Lambdin et al., 2018), which have been shown to reduce fatal overdose rates by as much as 46 % in communities where the drug is widely accessible (McDonald and Strang, 2016).

However, recent analyses highlight that there remain missed opportunities in prescribing naloxone to patients at increased risk of overdose. For instance, in 2018 only one naloxone prescription was dispensed for every 69 high-dose opioid prescriptions (Guy et al., 2019). In addition, 98.5 % of commercially insured patients at “high-risk” of overdose did not receive naloxone, despite many interactions with the health care system (Follman et al., 2019). Encouraging increased naloxone prescribing to these populations, as the laws we characterize generally seek to do, seizes the clinical encounter setting to engage patients in overdose harm reduction. Patients may be more likely to view naloxone possession and administration as legitimate if recommended by their treating clinician. Although about half of naloxone prescription laws lack an explicit education requirement, information about naloxone and overdose risk is likely to be delivered by the clinician at the time of recommending, offering, or writing the prescription. Even if patients do not ultimately fill a naloxone prescription, they are better educated about the risks of overdose due to this co-prescription initiative. If patients do fill naloxone prescriptions, the drug is available to them or their acquaintances to potentially reverse an overdose in an informed manner. Thus, mandated naloxone prescriptions may be warranted to change prescriber behavior, destig-matize naloxone, and facilitate effective use of the medication.

Still, these laws are not without limitations. Surveys suggest that providers lack information about how to prescribe naloxone and would prescribe more if better trained (Binswanger et al., 2015; Freise et al., 2018), yet with one exception (ME), no naloxone prescription laws include a prescriber education component. Similarly, these laws do not directly address other prescriber-identified barriers to naloxone prescribing (e.g., time, payer logistics) (Allen et al., 2019; Behar et al., 2017; Binswanger et al., 2015; Freise et al., 2018) or the out-of-pocket cost or stigmatizing concerns of naloxone prescriptions to many patients (Allen et al., 2019). For patients of less established overdose risk, the cost of purchasing naloxone, which is of particular import for branded formulations (Gupta et al., 2016), may not outweigh potential health benefits—highlighting the need for cost/benefit evaluations. Mandating naloxone prescribing may be viewed by providers as just adding to a growing list of opioid prescribing requirements. Less severe alternatives could lend clinical support for providing the naloxone prescription and training (Freise et al., 2018) without imposing a mandate. Finally, these prescribing requirements will do little to reach high-risk patients not interfacing with the health care system, who may be using more potent illicit synthetic opioids and in greater need of robust naloxone access. In all, improving naloxone access through a variety of channels—health care, community-based programs, and pharmacies—may be necessary to ensure that more populations in need are reached.

5. Conclusion

Given the rapid expansion in naloxone prescription laws over the past two years and new laws under consideration in a number of jurisdictions (e.g., TN, NY, DE), further quantitative and qualitative evaluation of these laws is warranted to understand the nature of any effects, including on overdose, and unintended consequences. Some work has demonstrated the acceptability of naloxone prescription requirements to primary care providers, but provider and patient concerns are relatively complex (Allen et al., 2019; Behar et al., 2017) and research should probe what additional levers could complement these laws to sustain their impacts and address persistent barriers to naloxone access in clinical settings. Furthermore, states that could benefit from naloxone prescription requirements, such as those in the Midwest where prescription opioids still account for a sizeable proportion of opioid harms (Jalal et al., 2018), may want to consider adopting these laws (Fig. 1). Although naloxone prescription laws seem well-intentioned and generally grounded in solid evidence, careful adoption and rollout may maximize their acceptability and effectiveness in reducing opioid overdose harms.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding

This research was supported by NIDA grant R21DA04595 and has benefited from our roles within the NIDA-funded Opioid Policy Tools and Information Center (P50-DA046351). Study supporters had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- Abouk R, Pacula RL, Powell D, 2019. Association between state laws facilitating pharmacy distribution of naloxone and risk of fatal overdose. JAMA Intern. Med. 179 (6), 805–811. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM, 2018. Increasing naloxone awareness and use: the role of health care practitioners. JAMA 319 (20), 2073–2074. 10.1001/jama.2018.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ST, White RH, O’Rourke A, Grieb SM, Kilkenny ME, Sherman SG, 2019. Take-home naloxone possession among people who inject drugs in rural West Virginia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 204, 107581 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMA, 2017. Help Save Lives: Co-Prescribe Naloxone to Patients at Risk of Overdose. Retrieved from. https://www.end-opioid-epidemic.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AMA-Opioid-Task-Force-naloxone-one-pager-updated-August-2017-FINAL-1.pdf.

- Behar E, Rowe C, Santos GM, Coffa D, Turner C, Santos NC, Coffin PO, 2017. Acceptability of naloxone co-prescription among primary care providers treating patients on long-term opioid therapy for pain. J. Gen. Intern. Med 32 (3), 291–295. 10.1007/s11606-016-3911-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, Gardner EM, Goddard K, Glanz JM, 2015. Overdose education and naloxone for patients prescribed opioids in primary care: a qualitative study of primary care staff. J. Gen. Intern. Med 30 (12), 1837–1844. 10.1007/s11606-015-3394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert ASB, Guy GP Jr., Losby JL, 2018. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Ann. Intern. Med 169 (6), 367–375. 10.7326/M18-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2016. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. Retrieved from Washington, DC:. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm?s_cid=rr6501e1_w.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Carr D, 2017. State legal innovations to encourage naloxone dispensing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc 57 (2), S180–S184. 10.1016/j.japh.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C, 2019. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: a national systematic legal review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 194, 166–172. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell D, Compton WM, Giroir BP, 2019. Patient-centered reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics: the HHS guide for clinicians. JAMA 1–3. 10.1001/jama.2019.16409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evoy KE, Hill LG, Groff L, Mazin L, Carlson CC, Reveles KR, 2018. Naloxone accessibility without a prescriber encounter under standing orders at community pharmacy chains in Texas. JAMA 320 (18), 1932–1937. 10.1001/jama.2018.15892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follman S, Arora VM, Lyttle C, Moore PQ, Pho MT, 2019. Naloxone prescriptions among commercially insured individuals at high risk of opioid overdose. JAMA Network Open 2 (5), e193209 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman PR, Goodin A, Troske S, Strahl A, Fallin A, Green TC, 2017. Pharmacists’ role in opioid overdose: kentucky pharmacists’ willingness to participate in naloxone dispensing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc 57 (2S), S28–S33. 10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freise JE, McCarthy EE, Guy M, Steiger S, Sheu L, 2018. Increasing naloxone co-prescription for patients on chronic opioids: a student-led initiative. J. Gen. Intern. Med 33 (6), 797–798. 10.1007/s11606-018-4397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertner AK, Domino ME, Davis CS, 2018. Do naloxone access laws increase outpatient naloxone prescriptions? Evidence from Medicaid. Drug Alcohol Depend. 190, 37–41. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio RE, Li G, DiMaggio CJ, 2015. Effectiveness of bystander naloxone administration and overdose education programs: a meta-analysis. Inj. Epidemiol 2 (1), 10 10.1186/s40621-015-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Case P, Fiske H, Baird J, Cabral S, Burstein D, Bratberg J, 2017. Perpetuating stigma or reducing risk? Perspectives from naloxone consumers and pharmacists on pharmacy-based naloxone in 2 states. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. Am. Pharm. Assoc 57 (2). 10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.013. S19−+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Shah ND, Ross JS, 2016. The rising price of naloxone - risks to efforts to stem overdose deaths. N. Engl. J. Med 375 (23), 2213–2215. 10.1056/NEJMp1609578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy GP, Haegerich TM, Evans ME, Losby JL, Young R, Jones CM, 2019. Vital signs: pharmacy-based naloxone dispensing — United States, 2012–2018. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 68 (31). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal H, Buchanich JM, Roberts MS, Balmert LC, Zhang K, Burke DS, 2018. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science 361 (6408). 10.1126/science.aau1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman JM, Robinson K, 2018. National systematic legal review of state policies on emergency medical services licensure levels’ authority to administer opioid antagonists. Prehospital Emerg. Care 22 (5), 650–654. 10.1080/10903127.2018.1439129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambdin BH, Davis CS, Wheeler E, Tueller S, Kral AH, 2018. Naloxone laws facilitate the establishment of overdose education and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 188, 370–376. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, Mutter R, Davis CS, Wheeler E, Kral AH, 2018. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addictive Behaviors. Behav 86, 90–95. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Strang J, 2016. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 111 (7), 1177–1187. 10.1111/add.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson BE, Agley JD, Davis A, Jayawardene W, Hoss A, Shannon DJ, Gassman R, 2018. Predicting pharmacy naloxone stocking and dispensing following a statewide standing order, Indiana 2016. Drug and Alcohol DependenceAlcohol Depend. 188, 187–192. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzantian T, Gasper JJ, 2018. Provision of naloxone without a prescription by California pharmacists 2 years after legislation implementation. JAMA 320 (18), 1931–1932. 10.1001/jama.2018.12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DI, Sabia JJ, Argys LM, Dave D, Latshaw J, 2019. With a little help from my friends: the effects of good samaritan and naloxone access laws on opioid-related deaths. J. Law Econ 62 (1), 1–27. 10.1086/700703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2018. Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit. Retrieved from Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, Lofwall MR, Freeman PR, 2019. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2 (6), e196215 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EL, Rao PSS, Hayes C, Purtill C, 2019. Dispensing naloxone without a prescription: survey evaluation of Ohio pharmacists. J. Pharm. Pract 32 (4), 412–421. 10.1177/0897190018759225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VG, Dwibedi N, 2017. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc 57 (2). 10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070. S12−+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Davis CS, Cruz M, Lurie P, 2018. State naloxone access laws are associated with an increase in the number of naloxone prescriptions dispensed in retail pharmacies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 189, 37–41. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller ND, Yokell MA, Green TC, Gaggin J, Case P, 2013. The feasibility of pharmacy-based naloxone distribution interventions: a qualitative study with injection drug users and pharmacy staff in Rhode island. Subst. Use Misuse 48 (8), 590–599. 10.3109/10826084.2013.793355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]