Abstract

The One Health concept is no longer new, but remains an accepted concept in modern disease control – where the interactions between animal health, human health, and the environment in which we live are recognised as being of importance. However, emerging infectious diseases often garner the greatest attention and resources. Parasitic infections, many of which are zoonotic but cannot truly be considered as emerging, must ensure that they retain their place under the One Health umbrella.

Keywords: emerging infectious disease, environment, One Health, zoonosis

Ten years have passed since the ‘Building Interdisciplinary Bridges to Health’ symposium was held at Rockefeller University, New York, resulting in the publication of a set of 12 priorities, the Manhattan Principles (Box 1 ; http://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/pdf/manhattan/twelve_manhattan_principles.pdf) and the emergence of the contemporary understanding of the ‘One Health’ concept – based on an international, interdisciplinary approach to disease prevention. Thus, the ‘One Health’ model should no longer be considered as a paradigm shift in our consideration of diseases but as an established and solid brick in modern disease control. However, although there has clearly been a rapid growth in acceptance of this concept over the last decade, as exemplified in a 2006–2012 literature review [1] that shows a continuous upward trend, this pattern is not globally distributed – and in the developing world, where zoonoses may have the greatest impact, the One Health approach has not been similarly taken on board.

Box 1. The Manhattan Principles.

The Manhattan Principles, which were developed in 2004 during the meeting ‘Building Interdisciplinary Bridges to Health in a “Globalized World”’ (http://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/pdf/manhattan/twelve_manhattan_principles.pdf), urge world leaders, civil society, the global health community, and institutions of science to approach holistically the prevention of epidemic/epizootic disease and the maintenance of ecosystem integrity by:

-

(i)

Recognizing the link between human, domestic animal, and wildlife health, and the threat disease poses to people, their food supplies and economies, and the biodiversity essential to maintaining the healthy environments and functioning ecosystems we all require.

-

(ii)

Recognizing that decisions regarding land and water use have real implications for health. Alterations in the resilience of ecosystems and shifts in patterns of disease emergence and spread manifest themselves when we fail to recognise this relationship.

-

(iii)

Including wildlife health science as an essential component of global disease prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation.

-

(iv)

Recognizing that human health programs can greatly contribute to conservation efforts.

-

(v)

Devising adaptive, holistic, and forward-looking approaches to the prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation of emerging and resurging diseases that fully account for the complex interconnections among species.

-

(vi)

Seeking opportunities to integrate biodiversity conservation perspectives and human needs fully, including those related to domestic animal health, when developing solutions to infectious disease threats.

-

(vii)

Reducing demand for, and better regulating, the international live wildlife and bushmeat trade, not only to protect wildlife populations but also to lessen the risks of disease movement, cross-species transmission, and the development of novel pathogen–host relationships. The costs of this worldwide trade in terms of impact upon public health, agriculture, and conservation are enormous, and the global community must address this trade as the real threat it is to global socioeconomic security.

-

(viii)

Restricting the mass culling of free-ranging wildlife species for disease control to situations where there is a multidisciplinary and international scientific consensus that a wildlife population poses an urgent, significant threat to human health, food security, or wildlife health more broadly.

-

(ix)

Increasing investment in the global human and animal health infrastructure commensurately with the serious nature of emerging and resurging disease threats to people, domestic animals, and wildlife. Enhanced capacity for global human and animal health surveillance, and for clear and timely information-sharing (taking language barriers into account), can only help to improve coordination of responses among governmental and nongovernmental agencies, public and animal health institutions, vaccine/pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other stakeholders.

-

(x)

Forming collaborative relationships among governments, local people, and the private and public (i.e., non-profit) sectors to meet the challenges of global health and biodiversity conservation.

-

(xi)

Providing adequate resources and support for global wildlife health surveillance networks that exchange disease information with the public health and agricultural animal health communities as part of early warning systems for the emergence and resurgence of disease threats.

-

(xii)

Investing in educating and raising awareness worldwide and in influencing the policy process to increase recognition that we must better understand the relationships between health and ecosystem integrity to succeed in improving prospects for a healthier planet.

Much of the One Health arena is dominated by reflections on, and approaches to, emerging infectious disease (EID) control (e.g., [2]). EIDs can indubitably represent a significant burden in terms of public health resources and national economies [3]. In addition, in some cases oubreak reportage spreads – quite rightly – into the news media, for example, regarding the ongoing spread of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [4] or the recent outbreak of Ebola in Guinea [5]. For this reason, infectious diseases that are categorised as EIDs tend to receive the lion's share of scientific and public attention and resources, although for some pathogens the ‘emerging’ label is often applied subjectively and without any quantitative support [6].

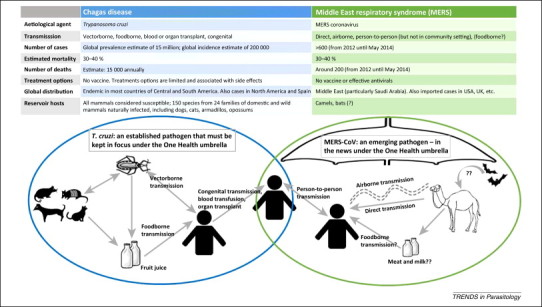

Nevertheless, from a One Health perspective it is important that not only EIDs take our attention. Analysis of a database of 335 EID events indicated that over 50% of these ‘emerging’ pathogens involved were bacterial, with the emergence of drug-resistant strains predominating, and over 25% were viral or prions [3]. This means that only around 10% of events were related to protozoa, whereas helminths, at a little over 3%, provided the least rattle on the EID Richter scale. Thus, from the EID perspective, parasitic infections are of relatively little significance, but that does not mean they are unimportant in terms of One Health as an approach to mitigation and control. In Figure 1 we compare some basic facts regarding MERS (an emerging viral infection) and Chagas disease (an established parasitic infection) to demonstrate that both emerging and established diseases should be considered to be significant.

Figure 1.

Chagas Disease and Middle East respiratory syndrome. Some facts and figures are presented for these important zoonotic diseases that both belong under the One Health umbrella.

There is no doubt that the spread of MERS and of other EIDs with high mortality and no available treatment options is important from a public health perspective, and unravelling the transmission routes deserves attention. However, established diseases such as Chagas, which are also associated with high morbidity, inadequate treatment options, and a variety of potential transmission routes, should also stay in focus under the One Health umbrella. Other important, but generally established and neglected, parasitic diseases that should be considered from a One Health perspective include fascioliasis, chlonorchiasis, cysticercosis, cryptosporidiosis, toxoplasmosis, and many others including vector-borne parasitoses such as leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, babesiosis, and filarial infections.

Thus, One Health seems to be recognised and accepted, with courses and, indeed, entire Masters degree studies dedicated to the subject being included on the curricula of different veterinary colleges and medical schools; for example, the One Health Institute of the University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, USA; the Center for One Health, University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, USA; Department of Environmental and Global Health, University of Florida, USA; Man-Animal-Food Health, Transdisciplinary Management of Global Health and Nutritional Safety, Oniris, France; Center for Global Health at the University of Wisconsin, USA; the Global Health Academy, University of Edinburgh, UK. Furthermore, various platforms addressing the One Health topic have been established, including for example The One Health Global Network (OHGN; http://www.onehealthglobal.net). Nevertheless, how we are to ensure the inclusion of parasitic infections into this enthusiasm for One Health seems less clear. In addition, care must be taken to make sure that parasitic infections do not become marginalised in the One Health fora as they compete for attention with more prominent and newsworthy topics.

In our opinion, it is disingenuous that researchers should try to seek the term ‘emerging’ for important pathogens to give them that extra focus; for instance, as recently as 2012 cryptosporidiosis was described in a publication as an ‘emerging zoonosis’ [7]. Although rare or unusual species of Cryptosporidium crossing between host species may perhaps be correctly described as emerging (e.g., C. ubiquitum in human infections [8]), cryptosporidiosis is well recognised as an established cause of diarrhoea, particularly in paediatric patients. That it is no longer ‘emerging’ does not mean it is not a serious public health concern, as exemplified by the study of Kotloff et al. [9], which demonstrated cryptosporidiosis to be the second most common cause of paediatric diarrhoea in various developing countries and is also associated with mortality in toddlers. Although this study [9] was able to identify the pathogens of greatest importance as a cause for paediatric diarrhoea, the One Health perspective of transmission and prevention was not considered; inclusion of this aspect in such studies, or as follow-up, could be of enormous value in countries where prevention may be a more practical approach to control than other strategies such as medication and hospital admission.

However, emerging or not, various parasites may have a relatively benign effect upon their human hosts unless particular circumstances arise; for example, (i) toxoplasmosis is often an uneventful infection, unless the host becomes immunosuppressed or first becomes exposed to the infection during pregnancy, and (ii) Taenia solium, despite its impressive size, has little serious effect on humans in their role as a definitive host, but when the human acts as an aberrant intermediate host the health outcome for the infected individuals may be critical. Similarly, when humans are not actually part of the regular lifecycle but become infected, such as in anisakiasis or alveolar echinococcosis, the pathology that occurs may be relatively severe. Thus, control of such parasites is important and, given that these four examples are all zoonotic, a One Health approach is clearly pertinent.

How adoption of One Health approaches to tackling both emerging and non-emerging zoonotic parasitoses can best be achieved remains an open question. Of the various scientific disciplines among health professionals, parasitologists have been described as being those who are most familiar with the long list of diseases in their specialty that affect both humans and animals [10]. However, as also pointed out, veterinary students tend to have far greater exposure to parasitology than do students of human medicine, largely owing to the greater volume of important parasitic infections among animals. This disparity results in considerable requirements for optimizing management in both human and animal species by utilizing One Health principles [10]. Furthermore, environmental scientists and other related non-health professionals, who nevertheless have a role to play in the One Health paradigm given the potential impacts of environmental factors on disease emergence and establishment [11], tend to have a limited overview, at best, of parasitic infections and their zoonotic potential. This knowledge is especially crucial today with globalisation and climate change apparently on the march; pathogens that were previously geographically restricted are now able to travel further – and survive the trip – and this is especially valid for the parasites with their vast biodiversity 12, 13.

Nevertheless, parasite-centric platforms and fora that use a One Health perspective are gradually becoming more prominent. Advocacy tools are being developed, such as www.theviciousworm.org that considers Taenia solium control from a One Health perspective. Furthermore, an FAO/WHO ‘expert’ group that considered from a global perspective the relative ranking of foodborne parasitic infections – the majority of which are zoonotic or have zoonotic potential – included individuals from a range of backgrounds: medical, veterinary, biology, etc. [14]. As a follow-up to this, a recent parasite-focus One Health workshop for medical/biomedical postgraduate students at a medical research establishment in India conducted a similar foodborne parasite ranking exercise, but at the national (Indian) rather than global level, and also discussed control options from a One Health standpoint (L.J.R. et al., unpublished). We believe that inclusion of One Health as a concept and a discussion point during parasitology sessions for medical students and veterinary students would be helpful. Simultaneously, and from the opposite angle, we believe it is important to safeguard that parasitic diseases continue to retain their place in both existing and developing One Health settings. Thus, the challenge as we see it may not be in adding parasites to the One Health bandwagon, but in ensuring that these frequently neglected infections, which are not necessarily acute but often represent an insidious burden, are not forgotten in the drama and panic surrounding other emerging zoonotic diseases that are hitting the headlines.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education for funding the ZooPa project (Project number: UTF-2013/10018) through the UTFORSK Programme that has enabled fruitful discussions among the authors on One Health and parasitology.

References

- 1.Bidaisee S., Macpherson C.N. Zoonoses and One Health: a review of the literature. J. Parasitol. Res. 2014;2014:874345. doi: 10.1155/2014/874345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabinowitz P., Conti L. One health and emerging infectious diseases: clinical perspectives. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;365:17–29. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones K.E. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialek S.R. First confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States, updated information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection, and guidance for the public, clinicians, and public health authorities – May 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014;63:431–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baize S. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea – preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funk S. Quantifying trends in disease impact to produce a consistent and reproducible definition of an emerging infectious disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;14:e69951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimani V.N. Social and gender determinants of risk of cryptosporidiosis, an emerging zoonosis, in Dagoretti, Nairobi, Kenya. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012;44(Suppl. 1):S17–S23. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li N. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:217–224. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.121797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotloff K.L. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case–control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan B. ‘One Health’ and parasitology. Parasit. Vectors. 2009;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones B.A. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:8399–8404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208059110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson L.J. Impacts of globalisation on foodborne parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utaaker, K.S. and Robertson, L.J. Climate change and foodborne transmission of parasites: a consideration of possible interactions and impacts for selected parasites. Food Res. Int., 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.06.051. [DOI]

- 14.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization Multicriteria-Based Ranking for Risk Management of Food-borne Parasites (Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Meeting, 3–7 September 2012, FAO Headquarters Rome Italy); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]