The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia, believed to have originated in a wet market in Wuhan, Hubei province, China at the end of 2019, has gained intense attention nationwide and globally. To lower the risk of further disease transmission, the authority in Wuhan suspended public transport indefinitely from Jan 23, 2020; similar measures were adopted soon in many other cities in China. As of Jan 25, 2020, 30 Chinese provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions covering over 1·3 billion people have initiated first-level responses to major public health emergencies. A range of measures has been urgently adopted,1, 2 such as early identification and isolation of suspected and diagnosed cases, contact tracing and monitoring, collection of clinical data and biological samples from patients, dissemination of regional and national diagnostic criteria and expert treatment consensus, establishment of isolation units and hospitals, and prompt provision of medical supplies and external expert teams to Hubei province.

The emergence of the 2019-nCoV pneumonia has parallels with the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which was caused by another coronavirus that killed 349 of 5327 patients with confirmed infection in China.3 Although the diseases have different clinical presentations,1, 4 the infectious cause, epidemiological features, fast transmission pattern, and insufficient preparedness of health authorities to address the outbreaks are similar. So far, mental health care for the patients and health professionals directly affected by the 2019-nCoV epidemic has been under-addressed, although the National Health Commission of China released the notification of basic principles for emergency psychological crisis interventions for the 2019-nCoV pneumonia on Jan 26, 2020.5 This notification contained a reference to mental health problems and interventions that occurred during the 2003 SARS outbreak, and mentioned that mental health care should be provided for patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonitis, close contacts, suspected cases who are isolated at home, patients in fever clinics, families and friends of affected people, health professionals caring for infected patients, and the public who are in need. To date, epidemiological data on the mental health problems and psychiatric morbidity of those suspected or diagnosed with the 2019-nCoV and their treating health professionals have not been available; therefore how best to respond to challenges during the outbreak is unknown. The observations of mental health consequences and measures taken during the 2003 SARS outbreak could help inform health authorities and the public to provide mental health interventions to those who are in need.

Patients with confirmed or suspected 2019-nCoV may experience fear of the consequences of infection with a potentially fatal new virus, and those in quarantine might experience boredom, loneliness, and anger. Furthermore, symptoms of the infection, such as fever, hypoxia, and cough, as well as adverse effects of treatment, such as insomnia caused by corticosteroids, could lead to worsening anxiety and mental distress. 2019-nCoV has been repeatedly described as a killer virus, for example on WeChat, which has perpetuated the sense of danger and uncertainty among health workers and the public. In the early phase of the SARS outbreak, a range of psychiatric morbidities, including persistent depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychomotor excitement, psychotic symptoms, delirium, and even suicidality, were reported.6, 7 Mandatory contact tracing and 14 days quarantine, which form part of the public health responses to the 2019-nCoV pneumonia outbreak, could increase patients' anxiety and guilt about the effects of contagion, quarantine, and stigma on their families and friends.

Health professionals, especially those working in hospitals caring for people with confirmed or suspected 2019-nCoV pneumonia, are vulnerable to both high risk of infection and mental health problems. They may also experience fear of contagion and spreading the virus to their families, friends, or colleagues. Health workers in a Beijing hospital who were quarantined, worked in high-risk clinical settings such as SARS units, or had family or friends who were infected with SARS, had substantially more post-traumatic stress symptoms than those without these experiences.8 Health professionals who worked in SARS units and hospitals during the SARS outbreak also reported depression, anxiety, fear, and frustration.6, 9

Despite the common mental health problems and disorders found among patients and health workers in such settings, most health professionals working in isolation units and hospitals do not receive any training in providing mental health care. Timely mental health care needs to be developed urgently. Some methods used in the SARS outbreak could be helpful for the response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak. First, multidisciplinary mental health teams established by health authorities at regional and national levels (including psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, and other mental health workers) should deliver mental health support to patients and health workers. Specialised psychiatric treatments and appropriate mental health services and facilities should be provided for patients with comorbid mental disorders. Second, clear communication with regular and accurate updates about the 2019-nCoV outbreak should be provided to both health workers and patients in order to address their sense of uncertainty and fear. Treatment plans, progress reports, and health status updates should be given to both patients and their families. Third, secure services should be set up to provide psychological counselling using electronic devices and applications (such as smartphones and WeChat) for affected patients, as well as their families and members of the public. Using safe communication channels between patients and families, such as smartphone communication and WeChat, should be encouraged to decrease isolation. Fourth, suspected and diagnosed patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia as well as health professionals working in hospitals caring for infected patients should receive regular clinical screening for depression, anxiety, and suicidality by mental health workers. Timely psychiatric treatments should be provided for those presenting with more severe mental health problems. For most patients and health workers, emotional and behavioural responses are part of an adaptive response to extraordinary stress, and psychotherapy techniques such as those based on the stress-adaptation model might be helpful.7, 10 If psychotropic medications are used, such as those prescribed by psychiatrists for severe psychiatric comorbidities,6 basic pharmacological treatment principles of ensuring minimum harm should be followed to reduce harmful effects of any interactions with 2019-nCoV and its treatments.

In any biological disaster, themes of fear, uncertainty, and stigmatisation are common and may act as barriers to appropriate medical and mental health interventions. Based on experience from past serious novel pneumonia outbreaks globally and the psychosocial impact of viral epidemics, the development and implementation of mental health assessment, support, treatment, and services are crucial and pressing goals for the health response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak.

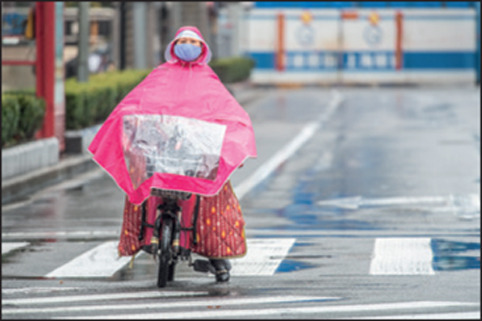

© 2020 VW Pics/Science Photo Library

Acknowledgments

Y-TX, YY, WL, LZ, and QZ contributed equally to this work. We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. published online Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X. Coronavirus outbreak: 444 new cases added on Friday. Jan 25, 2020. China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202001/25/WS5e2bad63a310128217273336.html

- 3.Xiang YT, Yu X, Ungvari GS, Correll CU, Chiu HF. Outcomes of SARS survivors in China: not only physical and psychiatric co-morbidities. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2014;24:37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. published online Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Commission of China Principles for emergency psychological crisis intervention for the new coronavirus pneumonia (in Chinese) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202001/6adc08b966594253b2b791be5c3b9467.shtml

- 6.Liu TB, Chen XY, Miao GD. Recommendations on diagnostic criteria and prevention of SARS-related mental disorders. J Clin Psychol Med. 2003;13:188–191. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei YL, Han B, Liu W, Liu G, Huang Y. Psychosomatic discomfort and related factors among 1,411 first-line SARS staff in Beijing. Manual of the 7th national experimental medicine symposium of Chinese Society of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine; Beijing, China; July, 2004: 6–12 (in Chinese).

- 10.Folkman S, Greer S. Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: when theory, research and practice inform each other. Psychooncology. 2000;9:11–19. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<11::aid-pon424>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]