Abstract

The most common atypical pneumonias are caused by three zoonotic pathogens, Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis), Francisella tularensis (tularemia), and Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), and three non-zoonotic pathogens, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Legionella. These atypical agents, unlike the typical pathogens, often cause extrapulmonary manifestations. Atypical CAPs are systemic infectious diseases with a pulmonary component and may be differentiated clinically from typical CAPs by the pattern of extrapulmonary organ involvement which is characteristic for each atypical CAP. Zoonotic pneumonias may be eliminated from diagnostic consideration with a negative contact history. The commonest clinical problem is to differentiate legionnaire's disease from typical CAP as well as from C. pneumoniae or M. pneumonia infection. Legionella is the most important atypical pathogen in terms of severity. It may be clinically differentiated from typical CAP and other atypical pathogens by the use of a weighted point system of syndromic diagnosis based on the characteristic pattern of extrapulmonary features. Because legionnaire's disease often presents as severe CAP, a presumptive diagnosis of Legionella should prompt specific testing and empirical anti-Legionella therapy such as the Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's weighted point score system. Most atypical pathogens are difficult or dangerous to isolate and a definitive laboratory diagnosis is usually based on indirect, i.e., direct flourescent antibody (DFA), indirect flourescent antibody (IFA). Atypical CAP is virtually always monomicrobial; increased IFA IgG tests indicate past exposure and not concurrent infection. Anti-Legionella antibiotics include macrolides, doxycycline, rifampin, quinolones, and telithromycin. The drugs with the highest level of anti-Legionella activity are quinolones and telithromycin. Therapy is usually continued for 2 weeks if potent anti-Legionella drugs are used. In adults, M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae my exacerbate or cause asthma. The importance of the atypical pneumonias is not related to their frequency (~15% of CAPs), but to difficulties in their diagnosis, and their nonresponsiveness to β-lactam therapy. Because of the potential role of C. pneumoniae in coronary artery disease and multiple sclerosis (MS), and the role of M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae in causing or exacerbating asthma, atypical CAPs also have public health importance.

Keywords: Atypical pneumonias, clinical diagnosis of legionnaire's disease, community-acquired pneumonia, doxycycline, legionnaire's disease, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Chlamydia pneumonia, quinolones, review, telithromycin, therapy of Legionella

INTRODUCTION

The term ‘atypical pneumonia’ was first applied to viral community-aquired pneumonias (CAP) that were clinically and radiologically distinct from bacterial CAPs. Over the past decades, atypical pneumonia has come to mean lower respiratory tract infections due to specific respiratory pathogens, i.e., Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis), Francisella tularensis (tularemia), Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Legionella species [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The newly recognised causes of CAP, i.e., severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), hantavirus, and avian influenza, are not considered ‘atypical pneumonias', but should be regarded as viral CAPs [5, 6].

Atypical CAPs represent approximately 15% of all CAPs. While outbreaks due to atypical pneumonia pathogens occur in the community, most cases of atypical CAP are sporadic. Atypical pulmonary pathogens causing pneumonia may also cause outbreaks of nursing home-acquired pneumonia (NHAP) or nosocomial pneumonia (NP). Atypical pneumonia as a cause of NHAP or NP is rare. Atypical pathogens are more common than typical bacterial pathogens in mild or ambulatory CAP in adults. Legionella is an important cause of severe CAP in hospitalised patients [4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10].

The atypical pneumonias may be classified clinically as those that are zoonotically transmitted and those that are not. The zoonotic atypical pneumonias include psittacosis, Q fever, and tularaemia, and the non-zoonotic atypical pneumonias include Mycoplasma, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella CAPs. Both the zoonotic and non-zoonotic atypical pneumonias differ fundamentally from bacterial CAPs. However, the main feature differentiating atypical from typical CAP pathogens is the presence or absence of extrapulmonary findings. All atypical pulmonary pathogens, both zoonotic and non-zoonotic, cause systemic infectious disease with a pulmonary component, i.e., pneumonia. Pneumonias caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis are typical CAPs with clinical and laboratory findings limited to the lungs. Once this distinction is made in CAP with extrapulmonary findings, the clinician can then determine the characteristic pattern of organ involvement and narrow down the diagnostic possibilities [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

Each atypical pulmonary pathogen has a predilection for certain extrapulmonary organ systems. It is the characteristic pattern of organ involvement rather than individual clinical or laboratory findings, that distinguishes the atypical pneumonias from each other. The extrapulmonary pattern of organ involvement of Legionella, for example, is very different and distinct from C. pneumoniae or Mycoplasma CAP, and provides the basis for a presumptive clinical diagnosis. If the distinctive patterns of extrapulmonary organ involvement associated with each atypical pathogen are recognised, a presumptive clinical diagnosis is usually straightforward and accurate. Presumptive clinical diagnosis is not definitive but should prompt specific diagnostic testing to confirm or rule out specific pathogens [1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10].

In the literature, most studies have been unable to clearly differentiate typical from atypical pneumonias. The main difficulty with such studies is that they have compared individual clinical and laboratory findings of atypical and typical pathogens. These studies correctly concluded that there are few, if any, discernible differences in isolated findings. Only rarely have studies used a syndromic diagnosis, and only one has used a weighted syndromic point system of diagnosis. Using a weighted syndromic approach based on the relative clinical specificity of characteristic clinical findings, it is clear that with good sensitivity and specificity, clinicians can not only differentiate typical from atypical pneumonias, but can accurately presumptively diagnose legionnaire's disease [11, 12, 13, 14].

The importance of the atypical pneumonias is not based on their clinical incidence per se, which is important enough, but rather on other clinical and public health aspects. The atypical pneumonias require a different therapeutic approach than that for typical CAPs [1, 2, 15]. Atypical CAP pathogens, particularly M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae constitute the majority of CAPs in young adults in the ambulatory or outpatient setting. The outpatient setting is the area where atypical pathogens are quantitatively more important than their typical CAP counterparts. Atypical pathogens, particularly Legionella, also are an important cause of severe CAP. Typical bacterial pathogens have classically responded to β-lactam antimicrobial therapy because they have a cell wall amenable to β-lactam disruption. In contrast, most of the atypical pathogens do not have a bacterial cell wall and some are intracellular, e.g., Legionella, and still others are paracellular, e.g., M. pneumoniae [1, 2, 9, 10].

Antimicrobials that inhibit or eradicate microorganisms by interfering with intracellular protein synthesis enzymes are effective against atypical pathogens. Macrolides and tetracyclines interfere with intracellular bacterial protein synthesis. Quinolones, and most recently ketolides, have been shown to be the most highly effective antimicrobials against atypical pathogens, particularly Legionella. Because some of the atypical pathogens are intracellular, e.g., Legionella, intracellular antibiotic penetration into alveolar macrophages (AM), is also important. Macrolides, tetracyclines, quinolones and ketolides concentrate in AMs [12, 16, 17, 18, 19].

Atypical CAP pathogens are quantitatively more important in the outpatient setting, and qualitatively important in hospitalised patients with severe CAP. There are also public health considerations that add to the importance of some atypical CAP pathogens. Aside from the potential role of C. pneumoniae in coronary artery disease and multiple sclerosis, it is clear that C. pneumoniae and M. pneumoniae infection may be complicated by asthma. M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae infection are also important causes of Non-exudative pharyngitis [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28].

Zoonotic atypical pneumonias have always been important causes of CAP in areas endemic for these infectious diseases. Psittacosis remains an important cause of CAP among those in contact with psittacine birds. Q fever occurs sporadically in those in close contact with parturient cats, or in sheep-raising areas. Endocarditis is an infrequent but important problem in endemic Q fever areas. Tularemia has six clinical presentations, any of which may be accompanied by pneumonia. In endemic areas tularaemia remains an important and potentially serious infectious disease [4, 7, 10, 29, 30, 31, 32].

Atypical pathogens are thus more important than estimates of their relative incidence would suggest in terms of diagnostic difficulties, nonβlactam susceptibility and their severity/complications.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF ATYPICAL PNEUMONIAS

If a patient presents with pneumonia, and in addition there are extrapulmonary findings, the patient has an atypical pneumonia. Patients with CAP plus extrapulmonary findings should, for clinical purposes, be further subdivided into those with zoonotic or non-zoonotic CAP. Zoonotic atypical CAPs due to Q fever, psittacosis, or tularaemia occur after contact with the respective vectors. Psittacosis is an exception and may be contracted after contact with well or ill psittacine birds. Tularemia and Q fever CAP are not random occurrences and a recent epidemiological contact history is required before considering the diagnosis. If a patient with an atypical pneumonia has a negative epidemiological contact history for psittacosis, Q fever, or tularaemia, it is extremely unlikely that the patient has a zoonotic atypical CAP, [6, 7, 21, 22, 23, 24] and it may be correctly assumed that the patient has a non-zoonotic atypical pneumonia due to Legionella, M. pneumoniae, or C. pneumoniae (Table 1 ) [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38].

Table 1.

Diagnostic features of the non-zoonotic atypical pneumonias. Adapted from Cunha, 2006 [6]

| Key Characteristics | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Legionnaire's disease | Chlamydophilia (Chlamydia) pneumoniae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Mental confusion | ±a | + | – |

| Prominent headache | – | ± | – |

| Meningismus | – | – | – |

| Myalgias | ± | ± | ± |

| Ear pain | ± | – | ± |

| Pleuritic pain | – | ± | – |

| Abdominal pain | – | + | – |

| Diarrhoea | + | + | – |

| Signs | |||

| Rash | ±b | – | – |

| Non-exudative pharyngitis | + | – | + |

| Haemoptysis | – | ± | – |

| Lobar consolidation | – | ± | – |

| Cardiac involvement | ±c | – | – |

| Splenomegaly | – | – | – |

| Relative bradycardia | – | + | – |

| Shock/hypotensiong | – | + | – |

| Chest X-ray | |||

| Infiltrates | Patchy | Rapidly progressive Asymmetrical ± consolidation | ‘Circumscribed’ lesions |

| Bilateral hilar adenopathy | – | – | – |

| Pleural effusion | ± (small) | ± | ± |

| Laboratory Abnormalities | |||

| WBC count | ↑/ N | ↑ | N |

| Hyponatraemia | – | + | – |

| Hypophosphataemia | – | + | – |

| Mild/early transient increased AST/ALT (SGOT/SGPT) | – | + | – |

| ↑ Cold agglutinins (≥ 1 : 64) | + | – | – |

| Microscopic haematuria | – | ± | – |

| Diagnostic Tests | |||

| Direct isolation (culture) | +d | +d | +d |

| Serology | CF | IFA | CF |

| Psittacosis CF litres | – | ↑ | ↑ |

| Legionella IFA litres | – | ↑↑↑ | – |

| Legionella DFA | – | +e | – |

| Legionella urinary antigen | – | +f | – |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CF, complement fixation; DFA/IFA, direct/indirect fluorescent antibody test; N, normal; WBC, white blood cell; +, usually present; ±, sometimes present; –, usually absent; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; ↑↑↑, markedly increased

rarely, only with Mycoplasma mengoencephalitis (cold agglutinins > 1 : 512)

erythema multiforme

myocarditis, heart block, or pericarditis

requires special media

rapidly becomes negative with anti-Legionalla therapy

may be falsely negative early, useful only Legionella pneumophila (serotype 01)

without acute cardiac/pulmonary events.

CLINICAL DIFFERENTIATION OF LEGIONELLA FROM OTHER TYPICAL AND ATYPICAL CAPS

To differentiate Legionella from S. pneumoniae CAP, cardiac, hepatic and renal abnormalities are most reliable. CNS manifestations may occur with S. pneumoniae CAP in patients who display mental confusion secondary to fever or hypoxemia. Patients with legionnaire's disease will have other non-CNS findings which will readily permit clinical differentiation between these two entities. The patient with S. pneumoniae and mental confusion will have no other extrapulmonary abnormalities, eliminating any potential diagnostic confusion. CNS abnormalities clearly illustrate the point that individual findings, e.g., mental confusion as an isolated clinical entity, are not helpful in distinguishing between typical and atypical pathogens. It is the pattern of extrapulmonary abnormalities that provides the basis for a syndromic diagnosis. The more abnormalities that are present, the more statistically certain is the presumptive clinical diagnosis [1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37].

Because each atypical pulmonary pathogen has a different pattern of extrapulmonary organ involvement, a presumptive clinical diagnosis can be made if the characteristic pattern of organ involvement is recognised by the clinician. It is relatively straightforward to differentiate Legionella from M. pneumoniae, but more difficult to differentiate M. pneumoniae from C. pneumoniae. In practice, the main clinical problem is to differentiate Legionella from S. pneumoniae and to differentiate Legionella from M. pneumoniae CAP. Based on the characteristic pattern of organ involvement, Legionella patients invariably have several of the following clinical or laboratory features: CNS abnormalities (headache, mental confusion, encephalopathy, lethargy); cardiac abnormalities (relative bradycardia); gastrointestinal manifestations (watery diarrhoea, abdominal pain); hepatic involvement (early or mild transient elevations of the serum transaminases); renal abnormalities (microscopic haematuria, increased creatinine); muscle involvement (elevated CPK and aldolase), and/or electrolyte abnormalities (hypophosphataemia, hyponatraemia). In contrast, the pattern of organ involvement characteristic of M. pneumoniae CAP excludes CNS involvement (except rarely in patients with meningoencephalitis); includes upper respiratory tract involvement (otitis, bullous myringitis, non-exudative pharyngitis); excludes cardiac involvement (no relative bradycardia, rarely myocarditis); includes gastrointestinal involvement (watery diarrhoea but not abdominal pain); excludes hepatic involvement; excludes muscle involvement; includes skin involvement (erythema multiforme); excludes renal involvement (rarely glomerulonephritis); and excludes electrolyte abnormalities. The distinctive laboratory feature of M. pneumoniae CAP is a highly elevated cold agglutinin titre (≥ 1 : 64) in ~75% of patients. It should be apparent that the most important characteristic features that distinguish Legionella from M. pneumoniae CAP are the presence of CNS, cardiac, hepatic, renal, and electrolyte abnormalities in Legionella infection, none of which are features of M. pneumoniae CAP [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38].

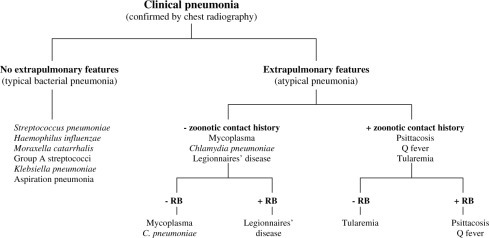

Not every patient with Mycoplasma pneumonia has an increase in cold agglutinins and those who do have increases that are early or transient. Thus the absence of increased cold agglutinins does not rule out M. pneumoniae infection. Highly elevated cold agglutinin titres (≥ 1 : 64) rule out non M. pneumoniae etiologies [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 37, 38] (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Clinical diagnostic approach to community-acquired pneumonias. RB, relative bradycardia. Adapted from Cunha BA [6, 36, 44].

CAP CO-INFECTIONS

Because co-infections, i.e., dual typical bacterial pathogens, dual atypical pathogens, or typical plus an atypical pathogen, are exceedingly rare there is no need to expend diagnostic resources looking for copathogens in patients with CAP. Studies that have reported typical or atypical copathogens have been based on culture for one and serology for the other. Serological diagnoses, particularly those based upon IgG titres, are problematic and are fraught with interpretational difficulties. Increased M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae IgG titres in a patient with CAP indicate past exposure and not active or concurrent infection. A patient with pneumococcal pneumonia and elevated IgG titres to M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae does not have co-pathogenicity but rather serological evidence of preexposure in a patient who actively has a single pathogen, i.e., S. pneumoniae [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43].

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF LEGIONNAIRE'S DISEASE

Legionella, among the non-zoonotic atypical pathogens, is the one that is most likely to be misdiagnosed or present as severe CAP. The presumptive diagnosis of legionnaire's disease may be made syndromically if the characteristic pattern of organ involvement of legionnaire's disease is present. As with other infectious diseases, some findings have greater diagnostic significance than others. The clinician should try to distinguish between clinical findings that are compatible with the diagnosis (nonspecific) and those that are characteristic in combination (specific). Some findings, such as mild transient elevations of the serum transaminases, often go unnoticed, or their diagnostic significance is unappreciated in a patient with CAP. Excluding noninfectious causes of mild serum transaminase elevations, and if Q fever and psittacosis can be eliminated on epidemiological grounds, the only non-zoonotic atypical CAP pathogen with mildly elevated transaminases is legionnaire's disease. Neither the diagnosis nor the suspicion of the diagnosis is based upon such a nonspecific finding alone. The mild elevations of the serum transaminases in a patient with CAP are important in the context of accompanying abnormalities, not because such elevations per se are diagnostic. Similarly, an otherwise unexplained borderline low normal or decreased serum phosphorous level in a patient with CAP should suggest the possibility of legionnaire's disease. No other typical or atypical CAP is associated with mild hypophosphataemia. Hyponatraemia, secondary to syndrome of inappropriate ADH(SIADH), may occur because of a variety of pulmonary disorders. Hyponatraemia is more common and severe in legionnaire's disease compared with other CAPs, but hyponatraemia is less diagnostically specific than hypophosphataemia. Without an alternate explanation, microscopic haematuria associated with CAP should also suggest the possibility of legionnaire's disease. Mild increases in serum creatinine which may be elevated due to a variety of other disorders, occur with Legionella. Microscopic haematuria is relatively more important than mild serum creatinine elevations in patients with possible Legionella CAP. Other laboratory tests that suggest Legionella are a highly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (≥ 30 units) in patients with CAP and extrapulmonary findings. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated in Legionella but is not helpful diagnostically compared with highly elevated CRP levels. In legionnaire's disease with muscle involvement or rhabdomyolysis, serum aldolase and creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels may be elevated. No other CAP with extrapulmonary manifestations is associated with these findings. Patients with legionnaire's disease invariably have some, but not all, of the aforementioned laboratory abnormalities, and the absence of any of them does not mean that the patient does not have legionnaire's disease. As mentioned previously, a highly elevated cold agglutinin titre (≥ 1 : 64) argues for the diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and strongly against the diagnosis of Legionella or C. pneumoniae [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 39] (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Clinical features of legionnaire's disease

| Organ | Common Features | Uncommon Features | Argues against involvement of legionnaire's disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | |||

| CNS | Headache, mental confusion, dullness, lethargy | Dizziness | Meningeal signs, seizures |

| HEENT | None | Vertigo | Sore throat, ear pain, bullous myringitis, otitis media |

| Cardiac | Relative bradycardia | Legionella endocarditis | Emboli to heart, joints, lungs, spleen, CNS |

| GI | Loose stools, watery diarrhoea | Abdominal pain | Hepatic tenderness, peritoneal signs |

| Renal | ↑ Creatinine | Acute renal failure | CVA tenderness, chronic renal failure |

| Laboratory features | |||

| CSF | Normal | Mild pleocytosis | RBCs, ↓ glucose,↑ lactic acid |

| WBC count (blood) | Leukocytosis | Leukopenia thrombocytopeniaThrombocytosis, | |

| Gram stain (sputum) | No bacteria | Few mononuclear cells, mixed flora | PMN predominance, predominant organismPurulent sputum, single |

| Pleural fluid | Exudative pattern | ↑ WBCs | RBCs,↓ pH, ↓ glucose |

| SGOT/SGPT | Mildly elevated (< 2 × normal) | Moderately elevated (> 2 × normal) | Markedly elevated (> 10 × normal) |

| Urine analysis | Microscopic haematuria | Proteinuria Myoglobulinuria | Gross haematuria, pyuria, hemoglobinuria |

CN, cranial nerve; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CVA, costovertebral angle; GI, gastrointestinal; HEENT, head, eyes, ears, nose and throat; LUQ, left upper quadrant; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis; RBC, red blood cell; RLQ, right lower quadrant; SBE, subacute bacterial endocarditis; WBC, white blood cell.

WINTHROP-UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL INFECTIOUS DISEASE DIVISION'S WEIGHTED POINT SCORE SYSTEM TO DIAGNOSE LEGIONNAIRE'S DISEASE

Particularly with Legionella CAP, it is key to distinguish extrapulmonary features compatible with the diagnosis from those characteristic of the diagnosis. Much of the problem in the literature is centred on this point. The failure of some studies to clinically differentiate legionnaire's diease from other typical or atypical pneumonias is based either on a comparison of isolated clinical or laboratory findings or an incorrect aggregation of findings. For a syndromic diagnosis to be accurate, it must be weighted, since characteristic findings have more diagnostic importance than those which are only consistent with the diagnosis [37, 38, 44, 45].

The single most important misunderstood and misinterpreted clinical sign associated with legionnaire's disease is relative bradycardia. In the literature, relative bradycardia, if described at all as a finding in legionnaire's disease, is never defined or is loosely described as a ‘pulse temperature deficit'. Relative bradycardia is a regular feature of legionnaire's disease and is a characteristic sign and constant finding in legionnaire's disease irrespective of the Legionella species [37, 38, 46].

If psittacosis and Q fever can be ruled out on epidemiological grounds in patients with CAP, relative bradycardia should suggest the possibility of legionnaire's disease. Relative bradycardia cannot be used as a diagnostic criterion in patients with pacemaker-induced rhythms, arrhythmias, or those on β-blocker medications. Temperature increases the pulse by ten beats/minute/°F in febrile states, and this relationship defines appropriate pulse/temperature relationships with any given degree of fever > 102°F. For example, in a patient with a 103°F temperature, the appropriate pulse response is ~120 beats/minute. In this patient, if relative bradycardia is present, the pulse is ≤ 120 beats per minute and often in the 80–90 beats per minute range. Pulse/temperature relationships are not altered by digitalis preparations, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, or ACE inhibitors, but only by β-blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem, verapamil). Any patient on a β-blocker who develops a fever will have relative bradycardia. For this reason, clinicians must be wary of incorrectly ascribing relative bradycardia to legionnaire's disease in cardiac patients on βblockers and fever. Exclusions and criteria aside, relative bradycardia is the most constant and important physical sign in legionnaire's disease. Relative bradycardia may also be associated with psittacosis or Q fever, but is not M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, or typical bacterial CAPs. A rapid way to clinically differentiate M. pneumoniae from Legionella CAP is by the presence or absence of relative bradycardia. Relative bradycardia in a patient with a zoonotic CAP should suggest Q fever or psittacosis but not tularemia. Relative bradycardia strongly favours the diagnosis of legionnaire's disease and effectively rules out M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae from further diagnostic consideration (Table 3, Table 4 ) [37, 38, 44].

Table 3.

Causes of relative bradycardia. Adapted from Cunha 2000, [46]

| Infectious Causes | Non-infectious Causes |

|---|---|

| Legionella | β-blockers diltiazem verapami |

| Psittacosis | CNS lesions |

| Q fever | Lymphomas |

| Typhoid fever | Factitious fever |

| Typhus | Drug fever |

| Babesiosis | |

| Malaria | |

| Leptospirosis | |

| Yellow fever | |

| Dengue fever | |

| Viral hemorrhagic fevers | |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | |

Table 4.

Determination of relative bradycardia. Reproduced with permission from Cunha, 2000 [46]

| Inclusive criteria: |

| (1) Patient must be an adult (2) Temperature ≥ 102°F (3) Pulse must be taken simultaneously with the temperature elevation Exclusive criteria: |

| (1) Patient has no arrhythmias, 2nd/3rd degree heart block, or a pacemaker-induced rhythm (2) Patient must not be on β-blocker medications, diltiazem verapami |

| Appropriate temperature-pulse relationships: |

| Temperature | Beats/min |

|---|---|

| 41.1 °C (106 °F) | 150 |

| 40.6 °C (105 °F) | 140 |

| 40.7 °C (104 °F) | 130 |

| 39.4 °C (103 °F) | 120 |

| 38.9 °C (102 °F) | 120 |

| 38.3 °C (101 °F) | 110 |

Symptoms characteristic of legionnaire's disease should be carefully looked for. In a patient with CAP, the presence of otherwise unexplained loose stools or diarrhoea limits diagnostic possibilities to M. pneumoniae and legionnaire's disease. Loose stools are more common than diarrhoea, and diarrhoea is watery with Mycoplasma and Legionella CAP. If a patient with CAP has abdominal pain with or without loose stools or diarrhoea, then Legionella is highly likely since no other cause of CAP is associated with acute abdominal pain [37, 38].

Negative findings argue strongly for an alternate diagnosis and are also helpful in ruling out legionnaire's disease. Upper respiratory tract involvement is characteristic of M. pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae CAP, but not of Legionella CAP. The presence of ear signs, laryngitis, or non-exudative pharyngitis in a patient with CAP suggests M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae as the most likely diagnostic possibilities, but also effectively rules out legionnaire's disease. Meningism or seizures argue strongly against Legionella infecion, but headache, mental confusion, encephalopathy or lethargy are consistent with it. Dermatological findings also effectively rule out legionnaire's disease from diagnostic consideration in a patient with CAP. A maculopapular facial rash (Horder's spots) should suggest psittacosis, a purple papule or extremity ulcer should suggest tularaemia, and erythema multiforme should suggest M. pneumoniae [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 37, 38, 44].

Combining positive and negative signs, symptoms, and laboratory features is the basis of a syndromic diagnosis based upon a weighted point system. The Winthrop-University Hospital point system for diagnosing legionnaire's disease has very good sensitivity and specificity. To date, it remains the best system for diagnosing legionnaire's disease. The weighted point system was intended to give the clinician a probability index to prompt specific testing for Legionella. The system was intended to increase awareness of Legionella, arrive at a presumptive clinical diagnosis, and prompt specific testing for Legionella. It has recently been modified with even better sensitivity and specificity than originally described in 1996. The weighted point system has been in use by the Infectious Disease Division at Winthrop-University Hospital for over a decade and the modified version remains the best way to diagnose legionnaire's disease [15, 46]. It is easily used and readily available for clinicians to assess the probability of legionnaire's disease in patients with CAP. If the system indicates high probability for Legionella, anti-Legionella therapy should be included in the empirical therapeutic regimen and specific tests for Legionella should be ordered (Table 5 ) [20, 47, 48, 49].

Table 5.

Modified Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's point system for diagnosing legionnaire's disease in adults. Adapted from Cunha, 2006 [6]

| Qualifying conditions | Point score | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | ||

| Temperature > 103°Fa | With relative bradycardia | + 5 |

| Headache | Acute onset | + 2 |

| Mental confusion/lethargya | Not drug-induced or metabolically/ hypoxemia related | + 4 |

| Ear pain | Acute onset | − 3 |

| Nonexudative pharyngitis | Acute onset | − 3 |

| Hoarseness | Acute not chronic | − 3 |

| Sputum (purulent) | Excluding chronic bronchitis | − 3 |

| Haemoptysisa | Mild/moderate | − 3 |

| Chest pain (pleuritic) | acute onset | − 3 |

| Loose stools/watery diarrhoeaa | Not drug induced | + 3 |

| Abdominal paina | With/without diarrhoea | + 5 |

| Renal failurea | Acute not chronic | + 3 |

| Shock/hypotensiona | Not 2° to acute cardiac | − 5 |

| /pulmonary causes | + 5 | |

| Splenomegaly | Excluding non-CAP causes | − 5 |

| Lack of response to β-lactams | After 72 h (excluding viral pneumonias) | + 5 |

| Laboratory Features | ||

| Chest X-ray | Rapidly progressive asymmetrical infiltratesa (excluding severe influenza/SARS) | + 3 |

| ↓ PO2 with ↑ A-a gradient (> 35)a | (Excluding severe influenza/SARS) | − 5 |

| ↓ Na+ | Acute onset | + 1 |

| ↓ PO4a | Acute onset | + 5 |

| ↑ SGOT/SGPT (early mild/transient) | Acute onset | + 4 |

| ↑ Total bilirubin | Otherwise unexplained | + 1 |

| ↑ LDH (> 400)a | Excluding HIV/PCP | − 5 |

| ↑ CPK/aldolase | Otherwise unexplained | + 4 |

| ↑ CRP (> 30) | Acute onset | + 5 |

| ↑ Cold agglutinins (≥ 1 : 64) | Acute onset | − 5 |

| ↑ Creatinine | Acute onset | + 2 |

| Microscopic haematuriaa | Excluding trauma, BPH, Foley catheter, bladder/renal neoplasms | + 2 |

| Likelihood of Legionella (total points) | ||

| > 15 Legionella very likely | ||

| 5–15 Legionella likely | ||

| < 5 Legionella unlikely | ||

Otherwise unexplained (acute and associated with pneumonia).

M. PNEUMONIAE AND C. PNEUMONIAE CAP

M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae CAP closely resemble each other in their clinical manifestations, but have some important distinguishing features. Firstly, M. pneumoniae is an acute infectious disease, while in contrast, C. pneumoniae may be acute but is typically a chronic disease. M. pneumoniae pneumonia, like other atypical pneumonias, is characterised by its pattern of extrapulmonary organ involvement [1, 2]. Mycoplasma has a predilection for the upper, as well as the lower, respiratory tract and thus patients with CAP who have upper respiratory tract involvement are most likely to have M. pneumoniae. Common upper respiratory tract manifestations of M. pneumoniae in a patient with CAP include otitis, bullous myringitis, and mild Non-exudative pharyngitis. These findings are less frequent with C. pneumoniae CAP. The most important clinical finding to differentiate Mycoplasma from C. pneumoniae is the presence or absence of laryngitis. Although all patients with C. pneumoniae CAP do not have laryngitis, the majority of them do. Patients presenting with a ‘mycoplasma-like illness’ with pneumonia-associated hoarseness should be considered as having C. pneumoniae until proven otherwise. Patients with CAP plus upper respiratory tract involvement and highly elevated cold agglutinin titres, i.e., ≥ 1 : 64, should be considered as having M. pneumoniae CAP until proven otherwise. Neither M. pneumoniae nor C. pneumoniae infection is characterised by cardiac or pulmonary involvement. Gastrointestinal involvement is typical for Mycoplasma, and is much less common with C. pneumoniae pneumonia. In a patient with CAP and otherwise unexplained watery diarrhoea associated with pneumonia, the differential diagnostic possibilities are limited to Legionella and Mycoplasma [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58]. In patients with advanced cardiopulmonary disease and in compromised hosts, M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae CAP may present as severe CAP [59, 60]. C. pneumoniae has been associated with outbreaks in nursing home aquired pneumonia (NHAP) [4, 57, 61].

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF ATYPICAL CAPS

Atypical pathogens are difficult to culture or dangerous to isolate. For this reason, clinical syndromic diagnosis is essential to increase suspicion of the diagnosis and begin appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy as well as to prompt specific diagnostic testing. Specific diagnostic testing is available for the atypical pathogens causing CAP. Legionella may be rapidly diagnosed by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) staining of sputum or respiratory secretions, pleural fluid, or lung specimens. DFA positivity in sputum decreases rapidly after initiation of anti-Legionella therapy. Indirect fluorescent antibody testing (IFA) showing a single titre ≥ 1 : 512 is also diagnostic. Alternately, a four-fold or greater rise in IFA IgG titres between acute and convalescent specimens is also diagnostic of legionnaire's disease. The Legionella antigen test has been useful in increasing Legionella awareness and providing another diagnostic test for L. pneumophila. If the Legionella antigen test is positive, it is (diagnostic of) L. pneumophila (serotype 01), but a negative test does not rule out legionnaire's disease. The Legionella antigen test is negative in non-L. pneumophila species and nonserotype 01 whose frequency depends on geographic distribution. The main advantage of the Legionella antigen test is that it remains positive for weeks to months after the onset of antigenuria, long after clinical resolution of the infection. The main disadvantage of the Legionella antigen test is that it is limited to one species, although L. pneumophila (serotype 01) is the most common Legionella species encountered. It takes several days for antigenuria to develop in the course of legionnaire's disease. If the test is ordered too early, it may be falsely negative as with early serological tests. Legionella may also be cultured on casitone-yeast extract (CYE) agar from sputum or respiratory secretions [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae may be cultured from respiratory secretions in special viral media. More commonly, the diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae is serological [56]. An acutely elevated M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae IgM titre in a patient with CAP is diagnostic. A four-fold increase in IgG M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae titres is indicative of past exposure or infection and is not diagnostic of acute infection or concurrent infection [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 62].

Because C. psittaci is difficult to isolate, diagnosis is entirely based on serological methods. Elevated tube agglutination (TA) tests for C. psittaci are diagnostic in nonimmune or previously unexposed patients. The diagnosis of tularemia and Q fever is also serological, since these organisms are highly infectious, dangerous, and difficult to isolate. In nonimmune, nonexposed persons acute elevations of F. tularensis IgM/IgG titres are diagnostic. Excluding high initial acute titres for Q fever or tularemia, the diagnosis of these zoonotic CAPs is based on a four-fold increase in titres between acute and convalescent specimens 4–8 weeks apart. Persistently highly elevated C. burnetii IgG levels indicate chronic Q fever infection rather than acute infection 4–10,29–32].

Radiologically, viral pneumonias typically have bilateral diffuse interstitial infiltrates without pleural effusion (with the exception of adenoviral pneumonia) or focal or segmental infiltrates plus or minus pleural effusion. Atypical pneumonias have no distinctive chest X-ray pattern. Pleural effusions may be seen with tularemia and Legionella and small effusions with M. pneumoniae. There is no specific chest X-ray pattern for Legionella, but rapidly progressive asymmetrical infiltrates are typical [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 63, 64, 65].

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY FOR ATYPICAL CAPS

Macrolides and Rifampin

During the initial outbreak of legionnaire's disease in Philadelphia, it was realised that patients did not respond to β-lactam therapy, but it soon became apparent that antimicrobials that worked intracellularly, i.e., macrolides and tetracyclines, were effective. Erythromycin was usually effective, but therapeutic failures did occur. For this reason, rifampin was added to increase anti-Legionella activity. Doxycycline has more inherent anti-Legionella activity than erythromycin or conventional tetracyclines, and has been used as an effective anti-Legionella agent for decades.

In addition to anti-Legionella activity, the other therapeutic consideration in treating legionnaire's disease is intracellular penetration. Legionella is an obligate intracellular organism and resides in the alveolar macrophage (AM). The eradication of intracellular pathogens is ordinarily difficult because many antibiotics do not concentrate intracellularly. Fortunately, all agents active against Legionella concentrate in the AM. The efficacy of erythromycin despite its limited anti-Legionella potency may be explained because it concentrates within the AM. Rifampin has anti-Legionella activity in vitro, but clinical experience with rifampin in combination therapy is limited. Rifampin should not be used alone because of the potential for the rapid development of resistance to other organisms. With doxycycline and newer more potent anti-Legionella agents, the rationale for erythromycin plus rifampin combination therapy has essentially been eliminated [5, 15, 61, 62, 66, 67].

Doxycycline

Doxycycline had a high degree of anti-Legionella activity and is more active than either erythromycin or tetracycline. If doxycycline is used to treat moderate to severe legionnaire's disease, then a loading regimen, not a loading dose, should be used to optimise the therapeutic response. For moderate to severe Legionella CAP, doxycycline should be administered at a dose of 200 mg (IV/PO) every 12 h for 72 h, and then the dose may be decreased to 100 mg (IV/PO) every 12 h for the duration of therapy. Because doxycycline displays concentration-dependent killing kinetics at high dose, it may also be administered as a single daily dose of 400 mg (IV/PO) every 24 h as part of the 3-day loading regimen or as 200 mg (IV/PO) for completion of therapy. To the best of my knowledge, there has not been a therapeutic failure using doxycycline when administered with a loading regimen in treating even severe Legionella CAP [4, 5, 6, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76].

Respiratory Quinolones

The quinolones have revolutionised anti-Legionella antimicrobial therapy. As good as doxycycline is, the fluoroquinolones are vastly superior in terms of anti-in-vitro activity. Fluoroquinolones, like other anti-Legionella antimicrobials, concentrate inAMto achieve high intracellular concentrations. Because of the potency of quinolones, particularly the ‘respiratory quinolones’ against Legionella species, there is no rationale for adding rifampin or any other anti-Legionella drug to quinolone therapy. There is sufficient clinical experience to confirm the in-vivo efficacy of the fluoroquinolones in treating legionnaire's disease. Because of the importance of atypical organisms in CAP (~15%), and in particular because of the potential for severe CAP with Legionella, the preferred empirical monotherapy for moderate/severe CAP is a ‘respiratory fluoroquinolone'. ‘Respiratory quinolones’ are highly active against the typical pathogens causing CAP, and are highly active against all of the zoonotic and non-zoonotic pathogens as well. Empirical ‘respiratory quinolone’ monotherapy offers many advantages including the simplicity, cost savings, pharmacokinetics and minimal drug reactions and as well as providing optimal coverage for typical and atypical pathogens using a single antimicrobial.

‘Respiratory quinolones’ have excellent bioavailability and lend themselves readily to intravenous/oral switch programmes. Patients receiving ‘respiratory quinolone’ oral therapy have the same blood and lung levels as those receiving the same dose intravenously. Critically ill patients may be started on intravenous therapy and should be switched to the oral equivalent as soon as the patient responds, if oral therapy can be given. With erythromycin and tetracycline, therapy for legionnaire's disease continued for 4–6 weeks to prevent relapse. Although clinical experience is limited, it appears that 2 weeks of therapy with highly active, anti-Legionella antibiotics, e.g., ‘respiratory quinolones', appear to provide adequate therapy [77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82].

Telithromycin

Ketolides also have a high degree of anti-Legionella activity. Telithromycin is a ketolide that is available at the present time only as an oral formulation. Telithromycin is useful therefore as monotherapy for the empirical treatment of mild to moderate typical/atypical CAP when oral therapy is desired. Telithromycin also may be used in switch therapy when therapy has been initiated with an intravenous anti-Legionella agent [83, 84, 85].

SEVERE CAP DUE TO ATYPICAL PATHOGENS

The severity of CAP is related primarily to the underlying immune status and cardiopulmonary function of the host. For this reason, pathogens of relatively low virulence, e.g., M. pneumoniae, in a patient with advanced lung disease can present as severe CAP. Of the atypical pathogens, Legionella is most likely to present as severe CAP requiring hospitalisation and ICU admission. Therapy of severe CAP is usually initiated intravenously, and after clinical defervescence, therapy may be switched to an oral equivalent [86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93].

IMPORTANCE OF M. PNEUMONIAE AND C. PNEUMONIAE

C. pneumoniae CAP closely resembles M. pneumoniae CAP. The epidemiology of C. pneumoniae also parallels that of M. pneumoniae except in NHAP. C. pneumoniae has been shown to cause outbreaks in patients in chronic care facilities and this has not been the case with M. pneumoniae. Both M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae CAP are most common in the ambulatory setting in young adults, but are responsible for a small number of patients who are hospitalised with CAP. M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae may present in patients with severely compromised respiratory function as severe CAP. M. pneumoniae, and to a lesser extent C. pneumoniae, may precipitate an attack of asthma or exacerbate existing asthma. Some patients who have recently had M. pneumoniae CAP develop post-CAP asthma which may be permanent. It would seem that M. pneumoniae which resides on the surface of the respiratory epithelium is in a perfect position to cause bronchial or hyper-reactivities and/or bronchospasm. The treatment of M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae CAP is important, not because of the severity of the illness, but if for no other reason, to decrease communicability and to decrease post-CAP asthma [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 94, 95].

C. pneumoniae has important public health implications in addition to CAP. C. pneumoniae chronic infection has been implicated in the aetiology of MS and coronary artery disease. Researchers at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine have used PCR and sophisticated diagnostic techniques to diagnose Chlamydia pneumoniae in patients with MS. They have achieved very good results, even in patients with far advanced MS, using prolonged anti-C. pneumoniae treatment. The role of C. pneumoniae in coronary artery disease remains controversial. Some trials have been conducted to evaluate the prophylactic value of antichlamydial prophylaxis in the prevention of CAD, but these studies have been inconclusive. Future studies will determine the role of C. pneumoniae in CAP and MS as well as other chronic infectious diseases [80, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100].

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray HW, Tuazon C. Atypical pneumonias. Med Clin North Am. 1980;64:507–527. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RE, Bates JH. Atypical pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1991;5:585–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi F. Atypical pathogens and respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:171–181. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00135703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrie TJ, editor. Community‐Acquired Pneumonia. Kluwer Academic; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karetzky M, Cunha BA, Brandstetter RD. The Pneumonias. Springer‐Verlag; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha BA. Pneumonia Essentials. Physicians Press; Royal Oak, MI: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levison ME, editor. The Pneumonias. John Wright PSG, Inc.; Boston: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennington JE, editor. Respiratory Infections. 3rd edn. Raven Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th edn. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR, editors. Infectious Diseases. 3rd edn. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT. Comparative clinical and laboratory features of Legionella with pneumococcal and mycoplasma pneumonias. Br J Dis Chest. 1987;81:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(87)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sopena N, Sabria‐Leal M, Pedro‐Botet ML. Comparative study of the clinical presentation of Legionella pneumonia and other community‐acquired pneumonias. Chest. 1998;113:1195–1200. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulazimoglu L, Yu VL. Can Legionnaire's disease be diagnosed by clinical criteria? A critical review. Chest. 2001;120:1049–1053. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez‐Sabé N, Roson B, Carratala B. Clinical diagnosis of Legionella pneumoniae revisited: evaluation of the community‐based pneumonia incidence Study Group scoring system. Clin Inect Dis. 2003;15:483–489. doi: 10.1086/376627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta SK, Sarosi GA. The role of atypical pathogens in community‐acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:1441–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunha BA. Antibiotic pharmokinetic considerations in pulmonary infection. Semin Respir Infect. 1991;6:168–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuler P, Zemper K, Borner K. Penetration of sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin into alveolar macrophages, epithelial lining fluid, and polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1130–1136. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10051130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honeybourne D. Antibiotic penetration in the respiratory tract and implications for the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1997;3:170–174. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199703000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller‐Serieys C, Soler P, Cantalloube C. Bronchopulmonary disposition of the ketolide telithromycin (HMR 3647) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3104–3108. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3104-3108.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunha BA. Antibiotic Essentials. Physicians Press; Royal Oak, MI: 2003. Antibiotic therapy; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esposito S, Principi N. Asthma in children: are Chlamydia or mycoplasma involved? Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3:159–168. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daian CM, Wolff AH, Bielory L. The role of atypical organisms in asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2000;21:107–111. doi: 10.2500/108854100778250860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdowell AL, Bacharier LB. Infectious triggers of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:45–66. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Micillo E, Bianoc A, D'Auria D. Respiratory infections and asthma. Allergy. 2000;55:42–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sessa R, Di Pietro M, Santino I. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerotic coronary disease. Am Heart J. 1999;137:1116–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ericson K, Saldeen TG, Lindquist O. Relationship of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection to severity of human coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2000;101:2568–2571. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamorano J, Garcia‐Tejada J, Suarez A. Chlamydia pneumoniae in the atherosclerotic plaques of patients with unstable angina undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: does it have prognostic implications? Int J Cardiol. 2003;90:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haim M, Tanne D, Battler A. Chlamydia pneumoniae and future risk in patients with coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2004;93:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg AN. Respiratory infections transmitted from animals. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1991;5:649–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill MV, Cunha BA. Tularemia pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;3(61):67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stubbs R, Dralle W, Williams J. Psittacosis pneumonia. J Tenn Med Assoc. 1989;82:189–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotton LM, Strampfer MJ, Cunha BA. Legionella and Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a community hospital experience. Clin Chest Med. 1987;8:441–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunha BA. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to the atypical pneumonias. Postgrad Med. 1991;90:89–101. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11701073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha BA. Community‐acquired pneumonia: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:43–77. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Atypical pneumonias. Postgrad Med. 1993;93:69–82. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1993.11701702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunha BA. Atypical pneumonias. In: Conn RB, Borer WZ, Snyder JW, editors. Current Diagnosis 9. W B Saunders; Philadelphia: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunha BA, Ortega AM. Atypical pneumonia. Extrapulmonary clues guide the way to diagnosis. Postgrad Med. 1996;99:131–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunha BA. The extrapulmonary manifestations of community‐acquired pneumonias. Chest. 1998;112:945. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lieberman D, Ben‐Yaakov M, Lazarowich Z. Chlamydia pneumoniae community‐acquired pneumonia: a review of 62 hospitalized adult patients. Infection. 1996;24:109–113. doi: 10.1007/BF01713313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marrie TJ. Community‐acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:501–505. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cunha BA. Community‐acquired pneumonias: reality revisited. Am J Med. 2000;108:436–437. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jokinen C, Heiskanen L, Juvonen H. Microbial aetiology of community‐acquired pneumonia in the adult population of 4 municipalities in eastern Finland. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1141–1154. doi: 10.1086/319746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.File TH, Jr, Tan JS, Plouffe JF. The role of atypical pathogens: Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila in respiratory infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;12:569–592. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunha BA. Clinical diagnosis of Legionnaire's disease. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13:115–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta SK, Imperiale TF, Sarosi GA. Evaluation of the Winthrop‐University Hospital criteria to identify Legionalla pneumonia. Chest. 2001;120:1064–1071. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunha BA. The diagnostic significance of relative bradycardia in infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:633–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.0194f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cunha BA. Pneumonia in the elderly. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:581–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marrie TJ. Community‐acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1066–1078. doi: 10.1086/318124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, Mandell LA. Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults: Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:347–382. doi: 10.1086/313954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beovic B, Bonac B, Kese D. Aetiology and clinical presentation of mild community‐acquired bacterial pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:584–591. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bochud PY, Moser F, Erard P. Community‐acquired pneumonia. A prospective outpatient study. Medicine. 1993;80:75–87. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marrie TJ. Epidemiology of mild pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Falguera M, Sacristan O, Nogues A. Nonsevere community‐acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1866–1872. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Honeybourne D. Community‐acquired pneumonia in ambulatory patients: relative importance of atypical pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:S57–S61. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marrie T, Peeling RW, Fine MJ. Ambulatory patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: the frequency of atypical agents and clinical course. A J Med. 1996;101:508–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hammerschlag MR. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almirall J, Morato I, Riera F. Incidence of community‐acquired pneumonia and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: a prospective multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunha BA. Ambulatory Community‐acquired pneumonia: The predominance of atypical pathogens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:579–583. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0996-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feldman C. Pneumonia in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2001;86:1493–1509. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurman G, Alkan M. Infectious atypical pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Isr J Med Sci. 1991;27:408–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mylotte JM. Nursing home‐acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1205–1211. doi: 10.1086/344281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hindiyeh M, Carroll KC. Laboratory diagnosis of atypical pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect. 2000;15:101–113. doi: 10.1053/srin.2000.9592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lynch DA, Armstrong JD., 2nd A pattern‐oriented approach to chest radiographs in atypical pneumonia syndromes. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12:203–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim EA, Lee KS, Primack SL. Viral pneumonias in adults: radiologic and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22:S137–S149. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc15s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sahn SA. Pleural effusions in the atypical pneumonias. Semin Respir Infect. 1988;3:322–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nightingale CH, Ambrose PG, File TM Jr, editors. Community‐Acquired Respiratory Infections. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alvarez‐Elcoro S, Enzler MJ. The macrolides. erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:613–634. doi: 10.4065/74.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smilack JD. The tetracyclines. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:727–729. doi: 10.4065/74.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunha BA. Pharmacokinetics of doxycycline. Postgrad Medical Comm. 1979;September:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Segreti J, House HR, Siegel RE. Principles of antibiotic treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia in the outpatient setting. Am J Med. 2005;118:21S–28S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marrie TJ. Empiric treatment of ambulatory community‐acquired pneumonia: always include treatment for atypical agents. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18:829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cunha BA. The virtues of doxycycline and evils of vancomycin. Adv Ther. 1997;14:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cunha BA. Macrolides, doxycycline and fluoroquinolones in the treatment of Legionnaire's disease. Antibiotics for Clinicians. 1998;2:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cunha BA. Doxycycline. Antibiotics for Clinicians. 1999;3:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cunha BA. Doxycycline re‐visited. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1006–1007. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cunha BA, Domenico PD, Cunha CB. Pharmacodynamics of doxycycline. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;6:270–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00058-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quintiliani R, Nightingale CH. Transitional antibiotic therapy. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1994;3:S161–S167. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge: a prospective observational study of 200 consecutive patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2449–2454. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.20.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramirez JA. Managing antiinfective therapy of community‐acquired pneumonia in the hospital setting: focus on switch therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:79S–82S. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.10.79s.34530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rhew D, Tu G, Ofman J. Early switch and early discharge strategies in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: a meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:722–727. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Castro‐Guardiola A, Viejo‐Rodriguez A‐L, Soler‐Simon S. Efficacy and safety of oral and early‐switch therapy for community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2001;111:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cunha BA. Intravenous to oral switch therapy in community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2001;23:78–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Quintiliani R. Clinical management of respiratory tract infections in the community: experience with telithromycin. Infection. 2001;29:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yassin HM, Dever LL. Telithromycin: a new ketolide antimicrobial for treatment of respiratory tract infections. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2001;10:353–367. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hammerschlag MR, Roblin PM, Bebear CM. Activity of telithromycin, a new ketolide antibacterial, against atypical and intracellular respiratory tract pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:25–32. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_2.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amsden GW. Treatment of Legionnaire's disease. Drugs. 2005;65:605–614. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marrie TJ, Durant H, Yates L. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: 5 year prospective study. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:586–599. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vergis N, Akbas E, Yu VL. Legionella as a cause of severe pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Medical. 2000;21:295–304. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garninger W, Zeitlinger M. Clinical applications of levofloxacin for severe infections. Chemotherapy. 2004;50:16–21. doi: 10.1159/000079818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cunha BA. Hepatic involvement in Mycoplasma pneumoniae community‐acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3456–3457. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3456-3457.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cunha BA. Severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Determinants of severity and approach to therapy. Infect Med. 2005;22:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cunha BA. Empiric oral monotherapy for hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: an idea whose time has come. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;22:579–583. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cunha BA. Severe community‐acquired pneumonias. J Crit Illness. 1997;12:711–712. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Plouffe JF. Importance of atypical pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:S35–S39. doi: 10.1086/314058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schlick W. The problems of treating atypical pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:111–120. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_c.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pucci E, Tauas C, Cartechini E. Lack of Chlamydia infection of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:390–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hao Q, Miyashita N, Matsui M. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection associated with enhanced MRI spinal lesions in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2002;8:436–440. doi: 10.1191/1352458502ms840oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Munger KL, Peeling RW, Hernan MA. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae and risk of multiple sclerosis. Epidemiology. 2003;14:141–147. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000050699.23957.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fainardi E, Castellazi M, Casetta I. Intrathecal production of Chlamydia pneumoniae‐specific high‐affinity antibodies is significantly associated to a subset of multiple sclerosis patients with progressive forms. J Neurol Sci. 2004;217:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Subramaniam S, Ljunggren‐Rose A, Yao S‐Y, Whetsell WO., Jr. Detection of chlamydial bodies and antigens in the central nervous system of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1219–1228. doi: 10.1086/431518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]