Dear Editor

We have read the article of Yavarian et al. [1], showing the prevalence of influenza and not of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in pilgrims and the general population. We would like to discuss the relevance of other respiratory viruses, including other CoV different to MERS-CoV, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoV (SARS-CoV) and the 2019 novel CoV (2019nCoV) [2] in relation to a case of coinfection between HCoV-229E, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and HIV we had in Colombia.

The three highly pathogenic viruses, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, 2019n-CoV, cause severe respiratory syndrome in humans, and the other four human coronaviruses (HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1) induce only mild upper respiratory diseases in immunocompetent hosts, although some of them can cause severe infections in infants, young children and elderly individuals [3].

Two years ago, a 32-year-old man admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for acute respiratory failure, five days after hospitalization, due to continuous productive cough (yellow secretion), nasal flaring, respiratory distress, intercostal retractions, sweating, chills and mucocutaneous paleness. During this admission, the patient tested HIV positive by ELISA and Western-blot. His initial CD4 cell count and viral load were 20 cells/μl and 759,780 copies/ml (PCR), respectively. Patient was started on combination antiretroviral treatment (ART) with a regimen of abacavir, lamivudine and efavirenz.

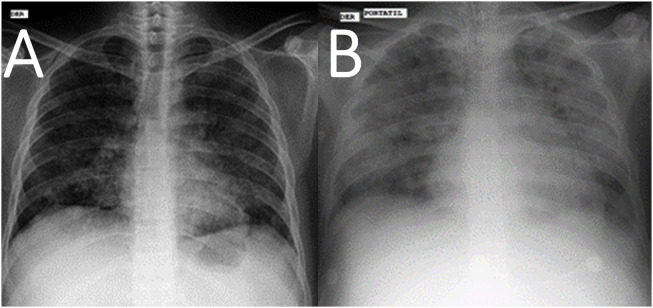

On ICU admission, he had fever of 37.6 °C (99.68 °F) and was mildly tachypnoeic. His blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg, with a pulse rate of 128/min. A chest radiograph showed bilateral micronodular infiltrates (Fig. 1 ). The patient's condition deteriorated rapidly, requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Arterial blood gas analysis showed severe hypoxemia with PaO2 of 70 mmHg and oxygen saturation of 60%, respiratory acidosis with PaCO2 of 52.3 mmHg, bicarbonate of 168 mmol/L, base excess of −6, lactate of 0.59 mmol/L. The ventilatory support consisted of controlled MV with low tidal volume (6 mL/kg), high respiratory rate (progressively increased up to 50/min), positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 10 cmH2O and FiO2 of 100%. Laboratory findings revealed acute renal failure (creatinine level, 2.0 mg/dl), anemia (hemoglobin, 7.1 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (58,000 platelets/mm3) and hyperkalemia (potassium 5 m eq/L). C-reactive protein, 96 mg/L; ESR, 20 mm/1h; CPK, 122 U/L; LDH, 1328 U/L. Patient received empirical antibiotic treatment with meropenem and vancomycin.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray of the patient at income (A) and ten days later (B).

A real-time RT-PCR test performed from a throat swab at the National Virology Reference Laboratory (Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogotá) confirmed the diagnosis of human coronavirus infection and typed the virus as 229E strain (HCoV-229E), but negative for HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HUK1 strains. Real-time RT-PCR for RSV also revealed a positive result, but negative for Influenza A, Influenza B, Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV), Adenovirus (AdV), Parainfluenza viruses (PIV) 1, 2, 3 and 4, Rhinovirus (RV), human Bocavirus (HBoV) and Enterovirus (EV).

Fourteen days after admission to ICU, and despite treatment with oseltamivir and aggressive supportive care with mechanical ventilation, fluid resuscitation, and high dose norepinephrine infusion, refractory hypoxia rapidly led to a fatal multiorgan failure. No autopsy was performed. Cultures of BAL fluid, blood and urine specimens remained negative for mycobacteria, and fungi. Only Escherichia coli from urine and Proteus mirabilis from BAL (both were susceptible to meropenem) were detected.

There is a lack of reported cases of a human coronavirus infection in HIV infected patients from Colombia and South America, confirmed by RT-PCR. HCoV-229E causes common cold but occasionally it can be associated with more severe respiratory infections in children [3,4], elderly and persons with underlying illness [3,5], which would be the case of HIV infection, as seen in this report [4,6].

The identification of coronavirus in high-risk immunocompromised patients may lead to early adoption of a specific therapeutic strategy, but, in the absence of proof of the efficacy of antiviral drugs, the treatment remains only supportive [5,7].

Evidence for a zoonotic origin of HCoV (eg. involving bats, camels), have been documented extensively over the past decade, including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and now the 2019n-CoV, which is causing epidemic and led to the World Health Organization to declare it as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [5]. In Colombia, the unique previous reference to coronaviruses was the identification of avian infectious bronchitis virus strains (an avian coronavirus, genus Gammacoronavirus) in Antioquia [8], a department close to Sucre, where our patient was diagnosed. The patient denied travelling recently to other regions of the country as well as internationally.

This case, similar to other non-MERS HCoV infection cases reported [7], is a reminder that although most infections with human coronaviruses are mild and associated with common colds, certain animal and human coronaviruses may cause severe and sometimes fatal infections in humans.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wilmer E. Villamil-Gómez: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Methodology. Álvaro Sánchez: Writing - review & editing. Libardo Gelis: Writing - review & editing. Luz Alba Silvera: Writing - review & editing. Juliana Barbosa: Writing - review & editing. Octavio Otero-Nader: Writing - review & editing. Carlos David Bonilla-Salgado: Writing - review & editing. Alfonso J. Rodríguez-Morales: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no reported conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

To Dr. Ziad Memish, Chair, Working Group on Zoonoses, International Society for Chemotherapy, for his critical review and advice for improve of the manuscript. This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Luz Alba Silvera, in memoriam.

References

- 1.Yavarian J., Shafiei Jandaghi N.Z., Naseri M., Hemmati P., Dadras M., Gouya M.M., Mokhtari Azad T. Influenza virus but not MERS coronavirus circulation in Iran, 2013-2016: comparison between pilgrims and general population. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2018;21:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biscayart C., Angeleri P., Lloveras S., Chaves T.D.S.S., Schlagenhauf P., Rodríguez-Morales A.J. The next big threat to global health? 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): what advice can we give to travellers? - interim recommendations January 2020, from the Latin-American society for Travel Medicine (SLAMVI) Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101567. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes M.C., Kuschner Z., Rabede Z. Clinical epidemiology of bocavirus, rhinovirus, two polyomaviruses and four coronaviruses in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African children. PloS One. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pene F., Merlat A., Vabret A. Coronavirus 229E-related pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(7):929–932. doi: 10.1086/377612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong A.T., Tsang O.T., Wong M.Y. Coronavirus infection in an AIDS patient. AIDS. 2004;18(5):829–830. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarado I.R., Villegas P., Mossos N., Jackwood M.W. Molecular characterization of avian infectious bronchitis virus strains isolated in Colombia during 2003. Avian Dis. 2005;49(4):494–499. doi: 10.1637/7202-050304R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]