Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to analyse characteristics and outcome of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in adults hospitalized with influenza-like illness (ILI).

Methods

Patients hospitalized with ILI were included in this prospective, multicentre study carried out in six French hospitals during three consecutive influenza seasons (2012–2015). RSV and other respiratory viruses were detected by multiplex PCR in nasopharyngeal swabs. Risk factors for RSV infection were identified by backward stepwise logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 1452 patients hospitalized with ILI were included, of whom 59% (861/1452) were >65 years and 83% (1211/1452) had underlying chronic illnesses. RSV was detected in 4% (59/1452), and influenza virus in 39% (566/1452). Risk factors for RSV infection were cancer (adjusted OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.1, p 0.04), and immunosuppressive treatment (adjusted OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.8, p 0.03). Patients with RSV had a median length of stay of 9 days (6–25), and 57% of them (30/53) had complications, including pneumonia (23/53, 44%) and respiratory failure (15/53, 28%). Fifteen per cent (8/53) were admitted to an intensive care unit, and the in-hospital mortality rate was 8% (4/53). Pneumonia was more likely to occur in patients with RSV than in patients with RSV-negative ILI (44% (23/53) versus 26% (362/1393), p 0.006) or with influenza virus infection (44% versus 28% (157/560), p 0.02).

Conclusion

RSV is an infrequent cause of ILI during periods of influenza virus circulation but can cause severe complications in hospitalized adults. Risk factors for RSV detection in adults hospitalized with ILI include cancer and immunosuppressive treatment. Specific immunization and antiviral therapy might benefit patients at risk.

Keywords: Respiratory syncytial virus, Pneumonia, Adults, Influenza-like illness, Influenza, Elderly

Introduction

Over the past decade, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been increasingly recognized as an important pathogen in adults [1], and especially the elderly [2], [3], [4], immunocompromised patients [5], [6] and individuals with underlying chronic respiratory diseases [7], [8]. In the elderly population, RSV is one of the three most common causes of respiratory disease, along with influenza virus and rhinovirus [3], [7].

Respiratory virus detection has improved with the development of highly sensitive and specific molecular methods, which are providing interesting new epidemiological information. However, for reasons of cost and the lack of RSV-specific antiviral drugs, adult inpatients with influenza-like illness (ILI) are frequently not tested for RSV but rather only tested for influenza virus. Influenza surveillance systems based on ILI and acute respiratory illness definitions are unsuitable for capturing cases of RSV in children and adults [9], [10], [11]. More studies are needed to determine the burden of RSV infection, and to characterize at-risk populations that could be targeted by vaccination and antiviral treatment. The aims of this study were to describe (a) the prevalence, (b) the clinical features, and (c) the outcome of RSV infection in adults hospitalized with ILI.

Materials and methods

Study design

We analysed cases of laboratory-confirmed RSV infection during three consecutive influenza seasons (2012/13, 2013/14 and 2014/15), in a post hoc analysis of patients hospitalized with ILI in the FLUVAC study. FLUVAC is a French prospective observational study of influenza vaccine efficacy conducted in six university hospitals (Cochin Hospital, Paris; Bichat Hospital, Paris; Pontchaillou Hospital, Rennes; Limoges Hospital; University Hospital, Montpellier; Edouard Herriot Hospital, Lyon). The FLUVAC study design is further described in Rondy et al. and Loubet et al. [12], [13]. Each season, enrolments take place during periods of influenza circulation (from November to March). Data on adults hospitalized for at least 24 h for ILI, with symptom onset <7 days before sampling, were collected. ILI was defined as a combination of the following: (a) at least one of the following systemic symptoms: fever (≥38°C), headache, myalgia or malaise, and (b) at least one of the following respiratory symptoms: cough, sore throat or dyspnoea [14]. Each participant was interviewed, and nasopharyngeal samples were obtained at enrolment.

Study population and data collection

We collected demographic characteristics, chronic underlying diseases and their treatments, the characteristics of the current ILI episode: clinical presentation, hospitalization ward, the length of hospital stay and outcome (occurrence of complication, intensive care unit admission and death). Data were retrieved from the medical charts, interviews with the patients and families, and laboratory databases. All variables collected are detailed in the Supplementary material (Appendix S1).

Laboratory data

Respiratory viruses were detected in nasopharyngeal swabs from all the patients by means of multiplex RT-PCR. Any bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples or tracheal aspirates ordered by the physician in charge were also tested.

Samples were first tested in the virology laboratory of each participating hospital by means of real-time influenza A and B PCR after manual nucleic acid extraction. All samples were then sent to the French National Influenza Reference Centre (CNR-Lyon) for influenza confirmation and screening for other respiratory viruses. RNA and DNA were extracted with the automated Easymag system from BioMérieux (Marcy l’Etoile, France), and influenza viruses were detected with an in-house real-time RT-PCR protocol [15]. The samples were also screened for a panel of other respiratory viruses (adenoviruses, bocaviruses, coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1–4, picornavirus and RSV) by real-time PCR using the Respiratory Multiwell System r-gene® on an ABI 7300 analyser.

Statistical analysis

We first described the characteristics of all the patients hospitalized with ILI. Then, univariate analysis was used to compare RSV-positive patients with (a) RSV-negative patients (including patients infected by other respiratory viruses and patients free of viral infection) and (b) influenza virus-positive patients. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), and qualitative variables as number and percentage. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test or Fisher’s exact test for univariable comparisons. Missing data for each variable were excluded from the denominator.

Factors associated with RSV infection were identified by using RSV-negative individuals as the comparison group. Individuals with influenza virus and RSV co-infection were excluded from the analysis. We used a backward stepwise logistic regression model, with RSV test results (positive/negative) as the dependent variable. All covariates with a p value <0.2 in univariate analysis were tested in the multivariate model, namely age (considered as a binary variable (<65 and ≥65 years)), dyspnoea, fever, myalgia, chronic lung disease, cancer (solid and haematological malignancies), diabetes, chronic renal failure, and immunosuppressive treatment. Factors associated with pneumonia onset were analysed among all ILI patients. Individuals with influenza virus and RSV co-infection were excluded from the analysis. We used a backward stepwise logistic regression model in which pneumonia (positive/negative) was the dependent variable. Covariates with a p value <0.2 in univariate analysis were tested in the multivariate model, namely age (considered as a continuous variable), chronic heart disease, chronic respiratory disease, cancer (solid and haematological malignancies), diabetes, chronic renal failure, immunosuppressive treatment, RSV infection, influenza virus infection, and influenza vaccination. The final model was adjusted for chronic respiratory disease and age because of their known role in the onset of pneumonia. Results from both regression models were expressed as odds ratios (OR) and adjusted ORs (aOR) with their 95% CI. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses used Stata software (V12, © Copyright 1996–2014 StataCorp LPt, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The FLUVAC study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02027233) respected Good Epidemiological and Clinical Practices in Clinical Research, and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by regional ethics committees. All the study participants gave their informed consent for respiratory virus testing.

Results

Characteristics of the patients with ILI, and virus distribution

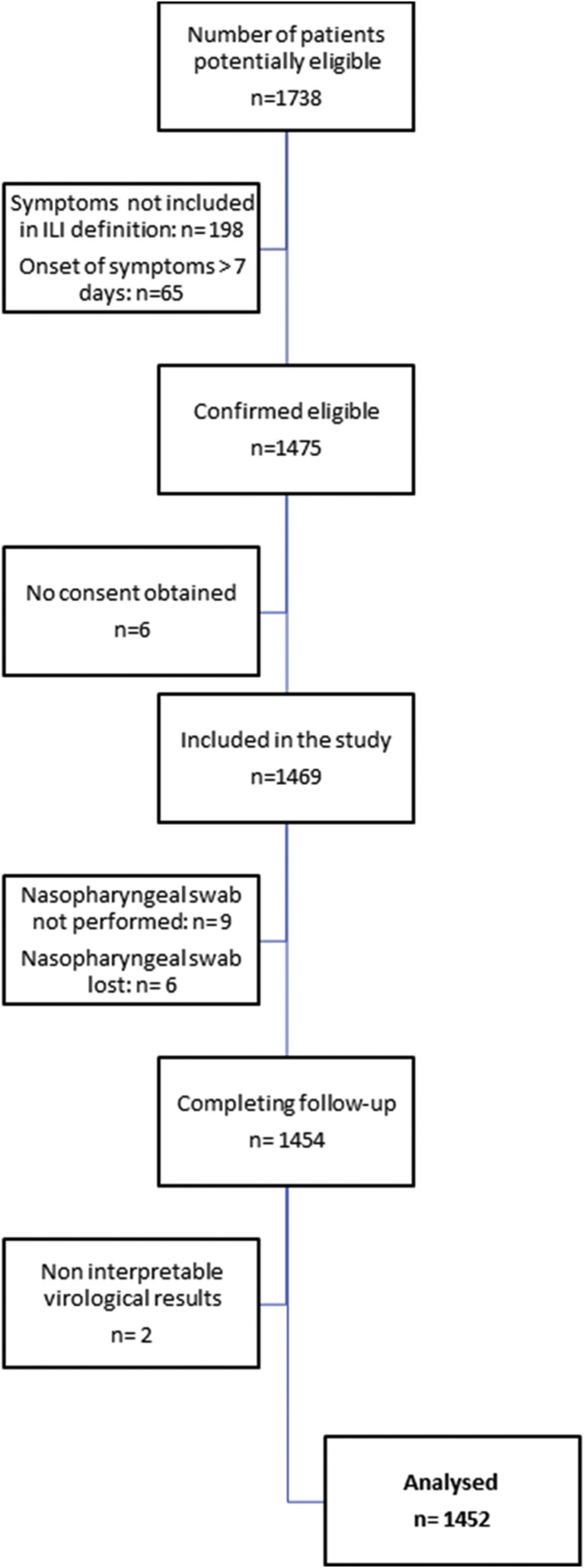

Overall, 1452 patients hospitalized with ILI were included during the three periods of influenza circulation (Fig. 1 ). Median age was 70 years (IQR 54–82), 83% of patients (1211/1452) had at least one chronic underlying disease (mainly chronic respiratory disease or chronic heart disease), 46% of patients (661/1452) had already been hospitalized in the previous 12 months, and 45% of patients (644/1431) had been vaccinated against influenza in the respective season.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart.

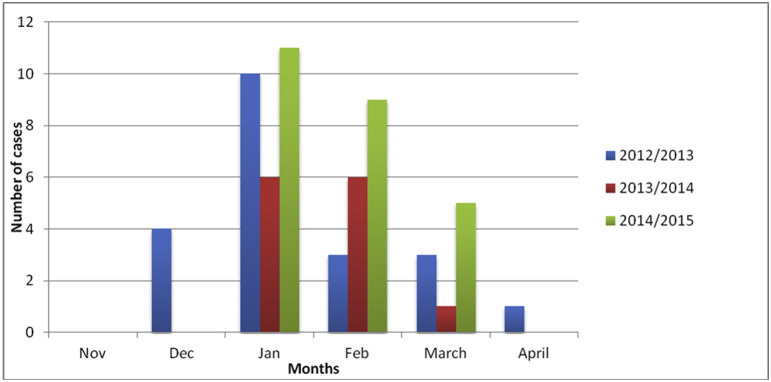

Among the 1452 patients tested, 777 patients (777/1452, 54%) were positive for at least one respiratory virus. Fifty-nine cases of RSV infection were detected in total (4% (59/1452) of patients with ILI, 8% (59/777) of patients with at least one respiratory virus), 21 in 2012/13, 13 in 2013/14 and 25 in 2014/15 (Table 1 , Fig. 2 ).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of patients hospitalized with influenza-like illness who tested positive for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus or any respiratory virus

| Season | At least one respiratory virus detected, n (%) | RSV n (%) |

Influenza n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012/13 n = 448 | 226 (50) | 21 (5) | 162 (36) |

| 2013/14 n = 407 |

188 (46) | 13 (3) | 112 (28) |

| 2014/15 n = 597 |

363 (61) | 25 (4) | 292 (49) |

| Total n = 1452 |

777 (54) | 59 (4) | 566 (39) |

Fig. 2.

Monthly distribution of respiratory syncytial virus infections in the FLUVAC study.

Respiratory syncytial virus was the third most frequent virus, after influenza virus (39% (566/1452) of patients with ILI, 73% (566/777) of patients with at least one virus) and picornavirus (5% (68/1452) of patients with ILI, 9% (68/777) of patients with at least one virus). The other detected viruses were coronavirus (3.5% (51/1452) and 7% (51/777) respectively), human metapneumovirus (3% (41/1452) and 5% (41/777)), adenovirus (1% (18/1452) and 2% (18/777)) and bocavirus (0.5% (8/1452) and 1% (8/777)). Six patients (6/1452, 0.4%) were diagnosed with both influenza virus and RSV infection and so were removed from further analyses.

Characteristics and outcome of RSV-positive patients

The median age of the 53 patients with RSV infection alone was 74 years (IQR, 61–84) (Table 2 ). Chronic underlying diseases were present in 45 cases (45/53, 85%), and consisted mainly of chronic respiratory diseases (29/53, 55%), chronic heart disease (24/53, 45%) and cancer (18/53, 34%; 12 solid tumours, 6 haematological malignancies). Fifteen patients (15/53, 28%) were on immunosuppressive therapy. Twenty-six patients (26/53, 49%) had been hospitalized in the previous year, an average of 1.4 times (SD 2.3).

Table 2.

Characteristics, clinical presentation and outcome of patients hospitalized with influenza virus or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection between 2012 and 2015 in six French university hospitals (excluding patients infected with both RSV and influenza virus).

| RSV + (n = 53) |

RSV– (n = 1393) |

p a | Influenza+ (n = 560) |

p b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Men, n (%) | 29/53 (55) | 751/1393 (54) | 1.0 | 284/560 (51) | 0.7 |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 74 (61–84) |

70 (54–82) |

0.13 | 68 (52–81) |

0.05 |

| Age ≥65 years, n (%) | 35/53 (66) | 825/1393 (59) | 0.39 | 321/560 (57) | 0.24 |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 23.4 (20.8–27.7) | 24.8 (21.5–28.7) | 0.15 | 24.8 (21.8–28.4) | 0.14 |

| Chronic diseases (at least one) | 45/53 (85) | 1162/1393 (83) | 1.0 | 466/560 (83) | 0.85 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 29/53 (55) | 630/1391 (45) | 0.21 | 249/559 (45) | 0.2 |

| Chronic heart disease | 24/53 (45) | 584/1391 (42) | 0.67 | 231/559 (41) | 0.66 |

| Diabetes | 8/53 (15) | 349/1391 (25) | 0.11 | 139/559 (25) | 0.13 |

| Chronic renal failure | 11/53 (21) | 182/1391 (13) | 0.15 | 69/559 (12) | 0.09 |

| Solid cancer | 12/53 (23) | 152/1391 (11) | 0.01 | 49/559 (9) | 0.003 |

| Haematological malignancy | 6/53 (11) | 67/1393 (5) | 0.04 | 25/559 (4) | 0.04 |

| Cirrhosis | 0 | 31/1391 (2) | 0.63 | 10/559 (2) | 1.0 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 15/53 (28) | 205/1393 (15) | 0.01 | 78/560 (14) | 0.01 |

| Pregnancy | 0 | 20/957 (2) | 1.0 | 9/421 (2) | 1.0 |

| Current smokers | 31/53 (58) | 693/1377 (50) | 0.27 | 271/551 (49) | 0.25 |

| Influenza vaccination in current season | 31/53 (58) | 610/1373 (44) | 0.05 | 234/555 (42) | 0.03 |

| ICU admission | 8/53 (15) | 205/1393 (15) | 0.85 | 81/560 (14) | 0.84 |

| Hospitalization in the previous 12 months | 26/53 (49) | 634/1389 (45) | 0.67 | 246/559 (44) | 0.56 |

| Mean number of hospitalizations in the previous 12 months (SD) among patients hospitalized at least once | 1.4 (2.3) | 1.1 (2.3) | 0.37 | 1.0 (2.1) | 0.24 |

| Presence of children <5 years old in household | 0 | 108/1393 (8) | 0.03 | 54/560 (10) | 0.01 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Median time from symptom onset to hospitalization, days (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.65 | 2 (1–3) | 0.35 |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 44/53 (83) | 1146/1392 (82) | 1.0 | 501/560 (89) | 0.17 |

| Cough | 43/53 (81) | 1087/1392 (78) | 0.74 | 457/560 (82) | 1.0 |

| Dyspnoea | 45/53 (85) | 1040/1393 (75) | 0.11 | 408/560 (73) | 0.07 |

| Sudden symptom onset | 12/31 (39) | 400/819 (48) | 0.28 | 139/271 (51) | 0.26 |

| Weakness/malaise | 12/53 (23) | 435/1393 (31) | 0.22 | 173/560 (31) | 0.27 |

| Headache | 10/53 (19) | 351/1392 (25) | 0.34 | 147/560 (26) | 0.32 |

| Myalgia | 6/53 (11) | 315/1391 (23) | 0.06 | 124/559 (22) | 0.08 |

| Outcome and treatment | |||||

| At least one complication during the hospital stay | 30/52 (58) | 635/1390 (46) | 0.09 | 275/560 (49) | 0.25 |

| Pneumonia | 23/52 (44) | 362/1390 (26) | 0.006 | 157/560 (28) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory failure | 15/52 (29) | 297/1390 (21) | 0.23 | 130/560 (23) | 0.39 |

| Acute heart failure | 10/52 (19) | 180/1390 (13) | 0.21 | 80/560 (14) | 0.31 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 7/52 (13) | 119/1390 (9) | 0.21 | 56/560 (10) | 0.47 |

| Median length of stay, days (IQR) | 9 (6–25) | 9 (4–22) | 0.4 | 10 (5–23) | 0.74 |

| Death | 4/53 (8) | 62/1393 (4) | 0.3 | 23/560 (4) | 0.28 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range

Comparison between RSV+ and RSV– patients.

Comparison between RSV+ and influenza virus+ patients.

The median time from symptom onset to admission was 2 days (IQR, 1–3). Cough (43/53, 81%), fever (44/53, 83%) and dyspnoea (45/53, 85%) were the main symptoms in patients with RSV infection.

The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (IQR 6–25). A total of 55 medical complications occurred in 30 patients (30/52, 58%) during their hospital stay, including pneumonia (23 episodes, 42% (23/55) of complications), respiratory failure (15/55, 27%), heart failure (10/55, 18%), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (7/55, 13%). Intensive care unit admission was necessary for eight patients (8/53, 15%). Four patients (4/53, 8%) died during the hospital stay; all of them were men >65 years old with chronic respiratory diseases. Furthermore, three patients had chronic heart disease. The mean time from admission to death was 13 days (SD 2.9).

RSV-positive patients versus RSV-negative patients and influenza virus-positive patients

Patients with RSV were older than patients with influenza virus (74 years (IQR 1–84) versus 68 years (IQR 52–81), p 0.05) (Table 2).

Patients with RSV were more likely to have cancer or immunosuppressive treatment than patients without RSV (respectively 34% (18/53) versus 16% (219/1393), p 0.002; 28% (15/53) versus 15% (205/1393), p 0.003) and influenza virus-positive patients (34% (18/53) versus 13% (74/560), p 0.004; 28% (15/53) versus 14% (78/560), p 0.01).

Multivariate analysis of all patients with ILI showed that cancer (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.1–4.1, p 0.04) and immunosuppressive treatment (OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.1–3.8, p 0.03) were significantly associated with RSV detection (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Factors associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in multivariable logistic regression (excluding patients infected with both RSV and influenza virus)

| Crude OR (95%CI) |

p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 years | 1.3 (0.8–2.4) | 0.39 | ||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1.5 (0.8–2.5) | 0.21 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.11 | ||

| Chronic renal failure | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | 0.15 | ||

| Cancer | 2.4 (1.2–4.6) | 0.01 | 2.1 (1.1–4.1) | 0.04 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 2.3 (1.2–4.2) | 0.01 | 2.0 (1.1–3.8) | 0.03 |

| Malaise at presentation | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.22 | ||

| Dyspnoea at presentation | 1.9 (0.9–4.1) | 0.11 | ||

| Myalgia at presentation | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.06 | ||

| Influenza vaccination | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | 0.05 |

The outcome analysed was RSV infection.

The patients with RSV and influenza virus infection did not differ in terms of the length of stay, ICU admission or mortality.

After adjustment for chronic respiratory disease and age, we found that RSV infection (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.2–3.8, p 0.008), chronic renal failure (OR 1.8; 95% CI 1.3–2.5, p 0.001) and active smoking (OR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0–1.7, p 0.02) were significantly associated with the onset of pneumonia (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Factors associated with pneumonia occurrence (n = 385) among hospitalized patients with influenza-like illness in multivariable logistic regression (excluding patients infected with both respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza virus)

| n/N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) |

p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | — | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.20 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.20 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 0.7 | 0.9 | |||

| No | 206/784 (26) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 179/657 (27) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | ||

| Chronic cardiac disease | 0.03 | — | — | ||

| No | 205/835 (25) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 180/606 (30) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | |||

| Diabetes | 0.9 | — | — | ||

| No | 291/1025 (27) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 94/356 (26) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | |||

| Chronic renal failure | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| No | 313/1249 (25) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 72/192 (38) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | ||

| Cancer | 0.15 | — | — | ||

| No | 314/1210 (26) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 71/232 (31) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | |||

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 0.6 | — | — | ||

| No | 323/1222 (26) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 62/220 (28) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |||

| Influenza vaccination | 0.5 | — | — | ||

| No | 205/783 (26) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 177/640 (28) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | |||

| Active smoking | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| No | 170/705 (24) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 212/722 (29) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | ||

| RSV infection | 0.005 | 0.008 | |||

| No | 362/1390 (26) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 23/52 (44) | 2.3 (1.3–3.9) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) | ||

| Influenza virus infection | 0.4 | — | — | ||

| No | 228/882 (26) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 157/760 (28) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.4 |

The outcome analysed was the occurrence of pneumonia during the hospital stay (n = 385).

The multivariate model was adjusted for 'chronic respiratory disease' and 'age >65'.

Continuous variable.

Discussion

In this study conducted during three consecutive influenza seasons among 1452 adults hospitalized for ILI in France, RSV was the third most common respiratory virus, being detected in 4% of patients, compared with 39% for influenza virus. This rate is lower than that found in the USA by Sundaram et al. in a community-based cohort of adults aged >50 years during six influenza seasons (184/2225, 8%) [3], or by Falsey et al. among community-based elderly individuals from 14 countries with moderate to severe ILI (41/556, 7%) [7]. In the latter study, the rate was even higher (8/64, 12.5%) among hospitalized patients. In another study, Falsey et al. reported a 10% (142/1388) prevalence of RSV among adults aged ≥65 years or with underlying cardiopulmonary diseases who were admitted with acute respiratory symptoms during four consecutive winters in Rochester, NY [1]. Several reasons may explain the broad range of reported RSV detection rates. For example, our study was restricted to periods of influenza virus circulation, which may not have included the peak of RSV circulation, although enrolments in the two studies by Falsey et al. started in mid-November. Another factor is age: we included all adults >18 years, whereas Sundaram et al. and Falsey et al. included only older subjects, in whom RSV infection may be more frequent. Furthermore, the laboratory methods used in the Rochester study included viral culture and serological tests, and RT-PCR was the only positive test in only two-thirds of cases. Finally, the clinical definition used to trigger swab collection also differed among the studies.

The median age of the RSV-infected patients in our study was 74 years but, contrary to other studies, we found no association between RSV infection and older age [3], [16], [17]. Most of the patients with RSV infection had chronic underlying conditions (45/53, 85%), consisting mainly of chronic respiratory disease (29/53, 55%) or chronic heart disease (24/53, 45%). This is consistent with the report by Walsh et al. that underlying pulmonary disease was a significant risk factor for severe RSV illness requiring hospitalization [18].

We found that the two underlying conditions independently associated with RSV infection were cancer and immunosuppressive treatment. This association was statistically significant whether RSV-positive patients were compared with all RSV-negative patients or only with influenza virus-positive patients. Although immunocompromised patients (especially patients with haematological malignancies) are known to be more susceptible to RSV infection [19], solid cancers and immunosuppressive therapy are not classical risk factors.

Respiratory syncytial virus was associated with significant morbidity: the median length of hospital stay was 9 days; 15% (8/53) of RSV-infected patients were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 8% (4/53) died. These findings are consistent with the literature [1], [20]. Similar percentages were noted in the influenza group of our study. Patients with RSV were significantly more likely than patients with influenza or without RSV to develop pneumonia (44% versus 28% and 26%, respectively). Falsey et al. and Lee et al. also found a high rate of pneumonia among 159 RSV-infected patients >65 years admitted for ILI in the USA (70/159, 44%) and among 607 RSV-infected adults admitted to three hospitals in Hong Kong (261/603, 43%) [20], [21]. Jain et al. [22] found at least one respiratory virus in 23% of 2259 American adults with community-acquired pneumonia requiring admission to one of five participating hospitals between 2010 and 2012. RSV was found in 3% (67/2259) of all patients.

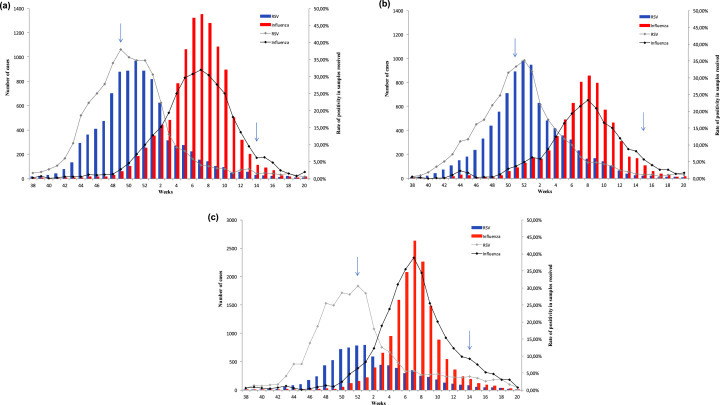

The strengths of this study include the large number of adults hospitalized with ILI, the prospective multicentre design, standardized patient screening in the participating centres, centralized confirmation of respiratory viruses in an influenza reference centre and the lengthy study period spanning three consecutive influenza seasons. Several limitations must, however, be acknowledged. First, as all the participating centres were teaching hospitals, the proportion of patients with underlying diseases may have been higher than in the general ILI population, owing to a referral bias. Second, although the sample was large, the study was probably underpowered to identify a possible impact of RSV on morbidity and mortality in multivariate analysis. Third, the ILI definition used here captures only a subset of RSV infections [10]. Our study does not reflect the real burden of severe RSV infection, which may include other clinical manifestations. Fourth, we report post hoc results of the FLUVAC study, which was not designed to answer this research question. Indeed, as the FLUVAC study was designed to assess influenza vaccine efficacy, patients were enrolled during periods of influenza virus circulation, which differ slightly from periods of RSV circulation. This means that our data reflect the prevalence of RSV among patients hospitalized for ILI during periods of influenza virus circulation and not during peak RSV circulation, which usually occurs earlier, owing to epidemiological interference [23]. However, French surveillance data (RENAL system) show that the peak of the RSV epidemic overlapped with the beginning of influenza virus circulation during the three seasons of interest, and that the two viruses co-circulated for at least 2–3 weeks (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus circulation in France during the 2012/13 (a), 2013/14 (b) and 2014/15 (c) seasons (data from the GROG, RENAL and Sentinelles surveillance networks) (arrows correspond to the start and end of fluvac study period).

In conclusion, this prospective observational study conducted in France during three influenza seasons reveals that 4% of adults hospitalized for ILI had RSV infection, of whom 58% developed cardiopulmonary complications and 8% died. It also shows that elderly individuals and patients with cancer and/or immunosuppressive treatment are more likely to have RSV isolated when hospitalized for ILI. Potential benefits of enhanced RSV testing, antiviral treatment, and vaccine development in these groups should be considered.

Transparency declaration

The authors declare no competing interest related to the study. O Launay is an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Janssen and other companies and received travel support to attend scientific meetings from pharmaceutical companies.

Funding

The current work received no funding. However, the study sites received funding from Sanofi Pasteur and Sanofi Pasteur MSD for the FLUVAC study. Vaccine producers had no role in the study design, data analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the RENAL network laboratories and the CNR laboratory for agreeing to share their data on influenza and RSV epidemics. We specifically thank Vincent ENOUF (CNR Influenza, Paris) for creation of Fig. 3.

We are very grateful to the following persons and institutions who made significant contributions to the FLUVAC study: Réseau National d’Investigation Clinique en Vaccinologie (I-REIVAC): K. Seddik, Z. Lesieur, N. Lenzi; InVS, France: I. Bonmarin; FLUVAC Study group: Hôpital Cochin, Paris: O. Launay, P. Loulergue, H. Bodilis, M. Servera-Miyalou, I. Sadler, S. Momcilovic, R. Kanaan, N. Coolent, K. Tan Boun, P. Blanche, J. Charpentier, F. Daviaud, N. Mongardon, A. Bretagnol, YE. Claessens, F. Rozenberg, A. Krivine. Hôpital Bichat Claude-Bernard, Paris: Y. Yazdanpanah, C. Burdet, S. Harent, M. Lachatre, C. Rioux, A. Bleibtreu, E. Casalino, C. Choquet, A. Leleu, K. Belghalem, L. Colosi, M. Ranaivoson, V. Verry, L. Pereira, E. Dupeyrat, J. Bernard, N. Emeyrat, P. Chavance, A. Debit, M. Aubier, P. Pradere, A. Justet, H. Mal, O. Brugiere, T. Papo, T Goulenok, M. Boisseau, R. Jouenne, JF. Alexandra, A. Raynaud-Simon, M. Lilamand, A. Cloppet-Fontaine, K. Becheur, AL. Pelletier, N. Fidouh, P. Ralaimazava, F. Beaumale, Y. Costa, X. Duval. Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon: E. Munier, F. Betend, S. Amour, S. Loeffert, K. Francourt. Hôpital Saint-Eloi, Montpellier: C. Merle, F. Galtier, F. Letois, V. Foulongne, P. Géraud, V. Driss, S. Noslier, M. Ray, M. Sebbane, A. Konaté, A. Bourdin, K Klouche, M.S. Léglise. CHU Dupuytren, Limoges: D. Postil, E. Couve-Deacon, D. Fruit, C. Fenerol, C. Vallejo, S. Alain, S. Rogez; CHU Pontchaillou, Rennes: P. Tattevin, S. Jouneau, F. Lainé, E. Thébault, G. Lagathu, P. Fillatre, C. Le Pape, L. Beuzit; Institut Pierre Louis d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique (IPLESP UMRS 1136): F. Carrat, F. Chau, I. Goderel et de Santé Publique (IPLESP UMRS 1136): F. Carrat, F. Chau, I. Goderel.

The authors thank Hélène Bricout, Laurence Pagnon and Christine Sadorge from Sanofi Pasteur MSD for their inputs during the study design phase and for critical review of the results.

Editor: C. Pulcini

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.014.

Contributor Information

O. Launay, Email: odile.launay@aphp.fr.

the FLUVAC Study Group:

K. Seddik, Z. Lesieur, I. Bonmarin, P. Loulergue, H. Bodilis, M. Servera-Miyalou, I. Sadler, S. Momcilovic, R. Kanaan, N. Coolent, K. Tan Boun, P. Blanche, J. Charpentier, F. Daviaud, N. Mongardon, A. Bretagnol, Y.E. Claessens, F. Rozenberg, Y. Yazdanpanah, C. Burdet, S. Harent, M. Lachatre, C. Rioux, A. Bleibtreu, E. Casalino, C. Choquet, A. Leleu, K. Belghalem, L. Colosi, M. Ranaivoson, V. Verry, L. Pereira, E. Dupeyrat, J. Bernard, N. Emeyrat, P. Chavance, A. Debit, M. Aubier, P. Pradere, A. Justet, H. Mal, O. Brugiere, T. Papo, T. Goulenok, M. Boisseau, R. Jouenne, J.F. Alexandra, A. Raynaud-Simon, M. Lilamand, A. Cloppet-Fontaine, K. Becheur, A.L. Pelletier, N. Fidouh, P. Ralaimazava, F. Beaumale, Y. Costa, E. Munier, F. Betend, S. Amour, S. Loeffert, K. Francourt, C. Merle, F. Letois, P. Géraud, V. Driss, S. Noslier, M. Ray, M. Sebbane, A. Konaté, A. Bourdin, K. Klouche, M.S. Léglise, E. Couve-Deacon, D. Fruit, C. Fenerol, C. Vallejo, S. Jouneau, F. Lainé, E. Thébault, P. Fillatre, C. Le Pape, L. Beuzit, F. Chau, F. Carrat, F. Chau, and I. Goderel

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following supplementary materials are available for this article:

Appendix S1.

References

- 1.Falsey A.R., Hennessey P.A., Formica M.A., Cox C., Walsh E.E. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang Z., Gonzalez R., Ren L., Xiao Y., Chen L., Zhang J. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of human respiratory syncytial virus in Chinese adults with acute respiratory tract infection. J Med Virol. 2013;85:348–353. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundaram M.E., Meece J.K., Sifakis F., Gasser R.A., Belongia E.A. Medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults aged ≥50 years: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:342–349. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClure D.L., Kieke B.A., Sundaram M.E., Simpson M.D., Meece J.K., Sifakis F. Seasonal incidence of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infection in a community cohort of adults ≥50 years old. PLOS One. 2014;9:e102586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson NW, Binnicker MJ, Harris DM, Chirila RM, Brumble L, Mandrekar J, et al. Morbidity and mortality among patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection: a 2-year retrospective review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (internet) (accessed 20 May 2016). Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S073288931630092X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Billings J.L., Hertz M.I., Wendt C.H. Community respiratory virus infections following lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2001;3:138–148. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2001.003003138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falsey A.R., McElhaney J.E., Beran J., van Essen G.A., Duval X., Esen M. Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viral infections in older adults with moderate to severe influenza-like illness. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1873–1881. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta J., Walsh E.E., Mahadevia P.J., Falsey A.R. Risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus illness among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2013;10:293–299. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.744741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S, Pandey BG, Choudekar A, Krishnan A, Gerber SI, Rai SK, et al. Evaluation of case definitions for estimation of respiratory syncytial virus associated hospitalizations among children in a rural community of northern India. J Glob Health (internet) (accessed 3 August 2016). Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4652925/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Talbot H.K., Falsey A.R. The diagnosis of viral respiratory disease in older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:747–751. doi: 10.1086/650486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meerhoff T.J., Mosnier A., Schellevis F., Schweiger B. 2009. Progress in the surveillance of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in Europe: 2001–2008.http://edoc.rki.de/browsing/docviews/abstract.php?lang=ger&id=321 (accessed 3 August 2016). Available at: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rondy M., Puig-Barbera J., Launay O., Duval X., Castilla J., Guevara M. 2011–12 Seasonal influenza vaccines effectiveness against confirmed A(H3N2) influenza hospitalisation: pooled analysis from a European network of hospitals. A pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loubet P., Samih-Lenzi N., Galtier F., Vanhems P., Loulergue P., Duval X. Factors associated with poor outcomes among adults hospitalized for influenza in France: a three-year prospective multicenter study. J Clin Virol. 2016;79:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Influenza case definitions (internet). (accessed 17 June 2015). Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/activities/surveillance/eisn/surveillance/pages/influenza_case_definitions.aspx.

- 15.Bouscambert Duchamp M., Casalegno J.S., Gillet Y., Frobert E., Bernard E., Escuret V. Pandemic A(H1N1)2009 influenza virus detection by real time RT-PCR : is viral quantification useful? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widmer K., Zhu Y., Williams J.V., Griffin M.R., Edwards K.M., Talbot H.K. Rates of hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and influenza virus in older adults. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:56–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou H., Thompson W.W., Viboud C.G., Ringholz C.M., Cheng P.-Y., Steiner C. Hospitalizations associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States, 1993–2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1427–1436. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh E.E., Peterson D.R., Falsey A.R. Risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly persons. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:233–238. doi: 10.1086/380907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falsey A.R., Walsh E.E. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:371–384. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.371-384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee N., Lui G.C.Y., Wong K.T., Li T.C.M., Tse E.C.M., Chan J.Y.C. High morbidity and mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1069–1077. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falsey A.R., Cunningham C.K., Barker W.H., Kouides R.W., Yuen J.B., Menegus M. Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A infections in the hospitalized elderly. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:389–394. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain S., Self W.H., Wunderink R.G., Fakhran S., Balk R., Bramley A.M. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:415–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casalegno J.S., Ottmann M., Bouscambert-Duchamp M., Valette M., Morfin F., Lina B. Impact of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic wave on the pattern of hibernal respiratory virus epidemics, France, 2009. EuroSurveillance Mon. 2010;1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.