Abstract

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was first diagnosed in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and has now spread throughout the world, being verified by the World Health Organization as a pandemic on March 11. This had led to the calling of a national emergency on March 13 in the US. Many hospitals, healthcare networks, and specifically, departments of surgery, are asking the same questions about how to cope and plan for surge capacity, personnel attrition, novel infrastructure utilization, and resource exhaustion. Herein, we present a tiered plan for surgical department planning based on incident command levels. This includes acute care surgeon deployment (given their critical care training and vertically integrated position in the hospital), recommended infrastructure and transfer utilization, triage principles, and faculty, resident, and advanced care practitioner deployment.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACS, acute general surgery; APP, advanced practice provider; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EGS, emergency general surgery; PPE, personal protective equipment; SCC, surgical critical care

The novel coronavirus that began in Wuhan, China in December 2019, now termed SARS-CoV-2, has caused a global impact on the health, politics, and economy in 3 short months. The clinical syndrome from the virus, now termed COVID-19, can consist of mild respiratory symptoms and fever, to adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death in severe cases. This has led to the disease being officially classified as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, and the US declared a State of Emergency on March 13, 2020.1 At the time of this writing (March 19), there are more than 220,000 confirmed cases worldwide, and 9,415 cases in the US, with 150 deaths.2 Many countries, states, and cities have instituted school, gathering, restaurant, and travel bans to mitigate its spread. Older patients and those with medical comorbidities are at the greatest risk of requiring hospitalization, ICU care, and at risk for death. In one of the largest epidemiologic studies to date from China, with widescale testing, 81% of all infected individuals had mild symptoms (fever, cough, malaise), 19% required hospitalization, and 5% required critical care; with an overall case-mortality rate of 2.3%. However, age ≥ 80 years was associated with a 14.9% case-fatality rate, 8% in the age 70 to 79 decade, and 49.0% in critically ill patients.3

As surgeons watching this event unfold in the US, we urge everyone to be prepared and to create a surgical department action plan in conjunction with key stakeholders and content experts vital to institutional response such as: emergency medicine, anesthesia, pulmonary critical care, infectious disease, internal medicine, facility and nursing management, and ultimately coordinated under the Incident Command System.4 Implementing screening by symptoms and exposure risk and mitigating healthcare personnel exposure to COVID-19 patients who require surgery is a key first step. Experience out of China5 and Singapore6 has demonstrated that screening by symptoms and routine testing, use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), and a coordinated plan involving all aspects of perioperative care are essential. However, the early and continued experience in Italy7 and Iran have demonstrated that when measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 are not implemented early enough, catastrophic scenarios requiring advanced triage criteria, resource management, and extreme flexibility within the healthcare system are required to save as many lives as possible. A review of crisis management principles relevant to healthcare in this pandemic and a tiered plan to take these factors into account was developed at our facility and is presented here. Key to understanding these concepts is the fact that patient surge is unlike typical mass casualty plans to which we have become accustomed, with an acute event (minutes to hours) followed by an acute and relatively short response (hours to days), but instead is a prolonged course of resource and personal exhaustion (weeks to months).

Our center

Atrium Health is one of the largest, integrated, public, not-for-profit healthcare systems in the US, compromising more than 7,500 licensed beds, employing nearly 70,000 people, and accounting for more than 12 million patient encounters, including 230,000 procedures, on an annual basis across acute care and ambulatory facilities in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center, Atrium Health Mercy Hospital, and Levine Children’s Hospital comprise the Central Division Campus in Charlotte. Carolinas Medical Center is an 874 bed, quaternary care hospital, American College of Surgeons-verified level I adult and pediatric trauma center. It serves as the University of North Carolina School of Medicine-Charlotte Campus and is the lead institution for the regional Metrolina Trauma Advisory Committee (MTAC). Carolinas Medical Center features a 29-bed dedicated surgical/trauma ICU, a separate 29-bed neurosurgical ICU, a 40-bed medical ICU, a 14-bed cardiac ICU, and virtual critical care services for Atrium Health. More than 300 ICU beds in Atrium Health are monitored virtually. Based on lessons from history, those already learned in the COVID-19 pandemic, and the following principles were used to create a tiered response plan for use in surgery departments throughout the US. Led by our division of acute care surgery (ACS) in coordination with emergency management and other stakeholders, this plan has been developed for, and is being disseminated through, our department of surgery and throughout all surgical subspecialties at all our facilities.

Social distancing

In the earliest weeks of the epidemic in Wuhan, isolation of patients, and then eventual quarantine of family, communities, and then whole cities, was seen. Although these concepts may be familiar to many, in the past weeks, an old concept, but new to many, has been disseminated to the country to decrease the spread of COVID-19: social distancing. This term includes measures from simply limiting unnecessary activities like large gatherings such as concerts, marathons, and sports games, to more drastic measures like banning all gatherings more than 50 people, closing schools city-wide and in some cases state-wide, and furloughing nonessential personnel from businesses.8 The goal of these measures is to reduce the spread of the virus so that the doubling time of the virus is increased, the purpose being to have fewer patients present in a shorter time period to hospitals.

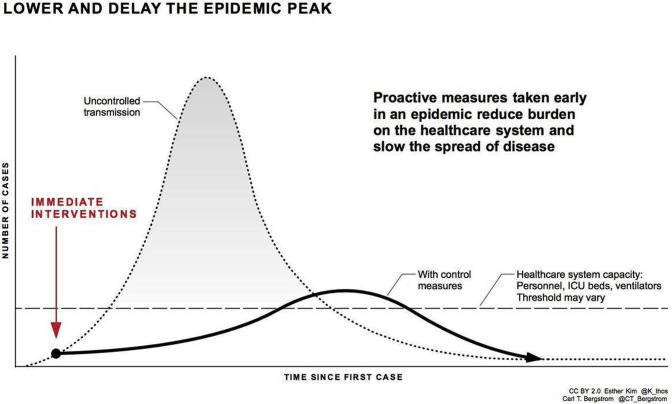

This has gone viral in the #flattenthecurve movement, with the publication of Carl Bergstrom’s graph illustrating the surge in patients on an exponential scale in relationship to the healthcare capacity as a flat line (Fig. 1 ). Measures such as social distancing would act to slow the spread and prolong the time frame of patients presenting to hospitals. As we have seen in Italy, when the steeper rise occurs, a higher number of deaths occur as patients who need intensive care and ventilators have long out-paced the available resources, and a rationing and triage of patients is required.7 However, with increased testing, meticulous contact tracing, and measured social distancing, South Korea has been able to decrease the rate of spread, and healthcare facilities have not become overburdened.9

Figure 1.

Principle of social distancing to reduce the curve of uncontrolled transmission to levels more sustainable to the healthcare system capacity. (Represented with permission from Carl T Bergstrom).

Resource management

Optimal disaster response necessitates knowledge, preparedness, and coordination to ensure adequate resource availability and allocation. This often requires difficult capacity and financial decisions during a preparation phase to make room for the anticipated influx of patients. Inherent in this is assessing the number of currently occupied beds, planned procedures, and admissions, and the maximum capacity for floor and ICU beds. More novel is what beds could be created in austere conditions by double bedding hospital and ICU rooms, conversion of postanesthesia care unit (PACU), operating rooms, and even hallways into ICU beds. A typical operating room could house 3 to 6 patients, depending on its size, and could be staffed by certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) and anesthesiologists as elective and even urgent cases are cancelled. Early and proactive bed management is key, as reports from Italy indicate that all noncritical and nonemergent care has ceased as the hospitals are now at 200% capacity.7 Given these capacity issues, systems are unable to provide adequate care for patients with everyday emergencies like stroke, myocardial infarction, and trauma. Therefore, the early COVID-19 mortality numbers fail to account for many patients who will have a concurrent preventable mortality from other causes as the result of this unanticipated surge and subsequent resource exhaustion.

Oxygen delivery and mechanical ventilation will undoubtedly be the highest-value resource given the presence in critically ill COVID-19 patients of respiratory failure (54%) and ARDS (31%).10 In general, the experience has been that noninvasive oxygenation modalities such as nasal cannula and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), are ineffective, and patients at this stage will need mechanical ventilation. Ingenuity with methods to create new ventilators from spare parts and retrofit old machines such as intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB) into working ventilators will be required. Additionally, if all patients are COVID-19 positive, as many as 4 patients could be linked in parallel on pressure control settings to attain reasonable minute ventilation and tidal volumes if required.11 Finally, while ventilators will be in high demand, endotracheal tubes are copious, and if family members are willing, bagging of patients by family members when no ventilator is available may be required.

Personnel attrition

First and foremost, a proactive response is needed to limit the unnecessary interactions and contact of all personnel in an effort to minimize exposure risk as early as possible. As the situation evolves, staffing will become dynamic, requiring a coordinated effort among physicians, advanced practice providers, and residents. Clear and definitive leadership will be required to best determine staffing and provider labor allocation for each facility. Buy-in from all respective division chiefs and departmental coordination will define and facilitate staffing levels. Situational flexibility will be paramount in conjunction with clear and efficient communication and multidisciplinary collaboration. All staffing plans must inherently assume attrition, and furloughs are required not only as the result of iatrogenic and community exposures, but also due to social instability, and/or resource consumption. As such, agreements should be in place to allow emergency credentialing and expansion of scope of practice to other facilities, as necessitated by the needs of the community. In large health systems, or even regional cooperatives, a pool of surgeons can be mobilized to start covering cases at satellite hospitals, as surgeons at these facilities are furloughed. Consideration should also be taken to minimize the risk to more senior partners to lower risk roles outside the hospital. Quarantined and senior surgeons can participate in telemedicine and even virtual critical care to increase the capacity to triage patients and care for the critically ill. Additionally, because this will be a prolonged surge if measures of social distancing are successful, there should be consideration of weekly rotating teams off service of faculty, advanced practice providers (APPs), and residents to not deplete or expose all providers at once.

Principles of the crisis standard of care should be used in disaster response when healthcare needs overwhelm available resources.12 At the highest response levels, plans for the advancement of senior residents and fellows to attending status may be required. Given the increased need for critical care expertise at this highest level, emergency general surgery (EGS) and trauma coverage should be transitioned to general surgery-trained elective surgeons to allow deployment of any surgical critical care (SCC)-trained physicians solely to the intensive care setting. We recommend a tiered reallocation of acute care surgeon (ACS) faculty as appropriate for each respective facility. At severe manpower shortage levels, non-ACS familiar with high-acuity priorities and hemorrhage control, like vascular, transplant, and hepatobiliary surgeons may be required to take trauma call. Additionally, at supra-maximum patient capacity, with decreasing providers in critical care and internal medicine, subspecialized surgeons will likely be called upon to become general physicians to treat the noncritical patients with COVID-19. However, every nurse, therapist, ancillary staff, and physician, regardless of specialty, should have some basic training in ventilator management, given the possibility of provider depletion and expansion of ICUs.

Trainee allocation

Learners inevitably play a role in large-scale responses, and preparations must strike a balance between patient safety and residents’ personal safety. Although an emergency plan is focused on patient care, it must also support workforce sustainability in the event of quarantine, illness, or injury. Resident participation in emergency preparedness plans is essential in hospitals with training programs. Planning for trainee allocation or quarantine has not been extensively studied. A hospital and graduate medical education department must decide the role trainees will play before their deployment is required, which will likely involve graduated promotion at the highest response level. The role of medical students should be carefully considered, with the default response being for them to be dismissed to isolation with the general public. The benefit provided to the affected population by students would be minimal compared with the risk of their exposure.

Evaluations and planning have focused on mass casualty incidents isolated to specific communities.13, 14, 15 There has been no published and distributed plan instituted for residents in a population health scenario such as that presented by COVID-19. For example, residents’ roles in the disaster response to the Boston Marathon bombing was unclear. There was no understanding if residents would be expected to provide surge staffing or if they would be stratified by experience.13 Though most hospitals train nurses and attendings for mass-casualty events, fewer than half train residents.14 , 15 This is a gap in medical education that should be addressed because these incidences are, unfortunately, becoming more frequent. Most resident staffing during crises is managed ad hoc by chief residents or program directors. Communications should be in place, whether by group text, online meeting applications, or other local mechanism, so that chief residents act as liaisons between institutional command, attending physicians, and resident teams. It is likely that trainees could be asked to work beyond scheduled duty hours. Local graduate medical education leadership should be involved in preparations, and knowledge of ACGME program requirements is essential. It is possible that residents will be asked to work beyond accepted duty hours, and these exceptions should be made known to the ACGME, but exemptions should be provided given the national emergency. Graduated autonomy and extension of attending physicians by senior residents as well as battlefield promotions of fellows and chief residents will be the most logical progression as the response to the crisis escalates and personnel are furloughed or quarantined.

Advanced triage criteria

Unfortunately, in a resource exhaustion and surge capacity, difficult ethical decisions will have to be made about which patients merit the use of a scarce resource. These types of discussions are usually reserved for organ allocation and in cases that require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Even in a normal situation in which your hospital only has 1 ICU bed, 1 ventilator, or 1 ECMO circuit left, the default is to still give it to the first patient who needs that resource. However, more complex in our current pandemic scenario is that the ventilator you are allocating today to the person with a poor chance of survival may deprive that resource tomorrow to the patient with a moderate chance of survival. Several schemas have been created in the past to rationalize the choices that are now in front of many healthcare providers, some of which are to maximize number of life years (favors the young), social value (favors occupations that are deemed valuable in preserving society infrastructure and culture), and instrumental value (those that would have impact on the current outbreak, like physicians and nurses).16

Currently in Italy, reports from over-capacity facilities describe making hard decisions to not intubate patients over 65 years old, and no ICU care to patients over 80.17 This type of rationing is unthinkable to most Americans with the perception that all aspects of healthcare are an inherent right up to and escalating toward death. Although many practitioners in the US will, rightly, not want to set hard limits like this, the withholding of surgery with recognition of futility is readily decided upon. Surgeons inherently understand futility in end-stage cancer, overwhelming sepsis, and advanced age and comorbidities. COVID-19 patients, with progression to ARDS and multiple risk factors, will have similarly dismal potential for survival. Therefore, in the vein of justice and maximizing benefit to all of society, advanced triage criteria based on individual risk factors should be performed before resources become exhausted to ensure that the next salvageable patient has the opportunity to benefit where the current patient likely will not.

Clinic triage and telemedicine

Given the rapid changes in technology as well as societal healthcare pressures due to the global pandemic, telemedicine should be the frontline triage for specialty surgery clinics.18

The limitations for use, such as costs, training, or HIPPA-related concerns, may limit the ability to rapidly upload and use these platforms for virtual visits, especially when faced with a rapidly progressing pandemic.19 However, many of these can be circumvented or expedited in the current state of emergency. For example, during the H1N1 pandemic, North and colleagues20 were able to use telephone screening triage to reduce unnecessary clinic visits, yet preserve medical access. In our specific ACS clinics, preoperative visits were stopped when the pandemic was declared and the US was seeing increasing numbers. Postoperative patients still need to be evaluated and managed for many issues, such as drains, wounds, and suture removal.

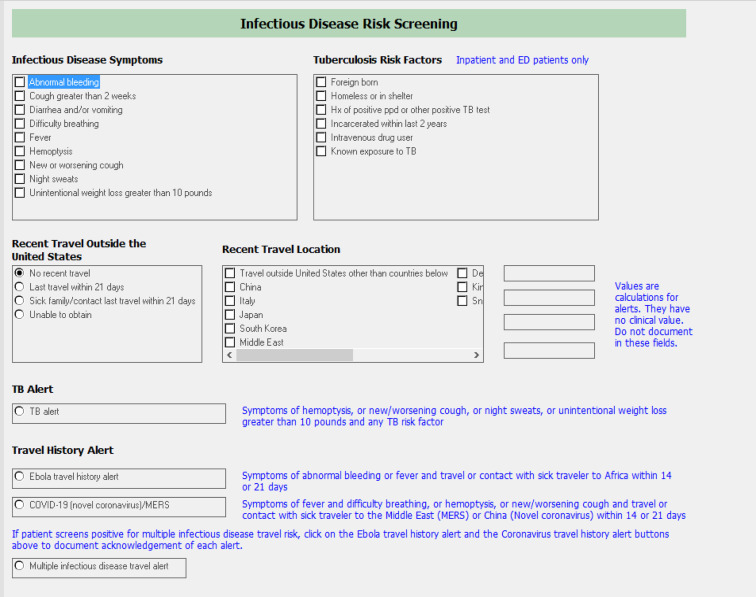

Due to the time constraints given the increasing community spread, we rapidly developed an ACS clinic patient screening process (eDocument 1), which started with already-scheduled patients for return to our trauma and EGS clinics. If a patient was determined not to need a virtual or physical visit, a telephone call was used to discuss the appointment and manage patient expectations. This tool evaluated not only whether they had medical issues requiring evaluation, but also screened for potential COVID infections, using the institutional infectious disease risk screening questions, embedded within the screening tool (eDocument 2). Using this risk tool allowed a patient who was high risk to be directed to a COVID-19 testing site. All patients designated for upcoming clinics are assessed the week before the clinic appointment and determined to: Not need to be seen physically nor virtually, and their situation is evaluated by a clinic nurse phone conversation; be an ideal candidate for a virtual clinic visit; or in need of objective data, such as a radiograph or laboratory blood work before clinic so the type of clinic visit can be determined. Due to the limited socioeconomic resources of most of our patients, many of our patients have access to only Android or Apple smart telephones, if any, so a computer video platform is not always viable.

We outfitted our clinic with 2 computers with video capability for patients calling into a virtual communication app (TEAMS) so these patients can connect with a computer, or Android or i-Phone device. We elected to use these technology methods for more rapid preparations for virtual evaluations in the clinics and due to the time constraints of the forced social distancing mandates of the community. After reviewing the previously completed screening tool on a patient, an ACS physician or APP perform the virtual visit using a standard virtual exam template (eDocument 3). With the information gleaned from the screening tool and the virtual exam, a management plan is individualized for each patient and the forms are scanned into patients’ electronic medical records along with a documented clinic note.

If patients require a physical appointment in our ACS clinic, they are screened again on arrival for symptoms of a potential COVID-19 infection. Only 1 additional caregiver or family member can accompany the patient. In order to improve social distancing in the waiting rooms, all chairs are kept 6 feet apart. On arrival to the clinic, if a patient has any active symptoms of a COVID-19 infection, he or she is directed to a testing site appropriate for their symptoms, per institution protocols. Only 1 nurse and 1 attending can evaluate the patient. Using these methods, in the first week of implementation, of 21 scheduled ACS clinic patients, we have already identified 19 patients able to be managed by virtual or telephone visits (91% reduction in clinic visit exposure). Contact has been completed and they are being managed virtually, revealing a potential 91% reduction in clinic visits. Objective data are being obtained for 2 patients (chest radiographs and laboratory values) to determine whether they will require a physical clinic visit. One of these 2 patients has staples that will be removed via a nurse visit or at their primary care provider’s office, since they live more than 1 hour away from our clinic office. Although we are early in the process, transitioning our ACS clinics to a virtual/telemedicine process, with appropriate resources, will continue to allow us to keep patients safe from exposure, preventing potential exposure risk to healthcare staff, as well as maintaining patient safety and perioperative surgical expectations.

Tiered response

In reflection of the above principles, led by acute care surgeons with familiarity in disaster preparedness and public health, in conjunction with the incident command structure, and in an effort to keep in mind a prolonged surge of COVID-19 patients, the following Surgery Department COVID-19 Response Plan was created (Table 1 ). This has now been disseminated and adapted to each facility and subspecialty surgical service, and is being pivoted to other specialties such as pulmonary critical care and internal medicine within Atrium Health. Key in understanding the response level is each individual facility’s incident command response level, which follows a similar structure to that set by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).4 , 12 However, new to this schema is ConditionZero, which indicates patient surge and acuity beyond the capacity of the infrastructure and manpower available, a scenario currently being experienced in Italy, Iran, and progressively, around the world. Advancement to higher tiers should follow incident command structure, but may also be required within individual specialties, departments, or division plans given manpower and resource depletion.

Table 1.

Surgery COVID-19 Activation and Response Plan

| Activation | Threshold for activation/possible ACS impact | Surgery department response | Recommended facility response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alert |

|

|

|

| Level 2 |

|

|

|

| Level 1 |

|

|

|

| Level 0 |

|

|

|

ACS, acute care surgery; APP, advanced practice provider; CAD, coronary artery disease; CC, critical care; CV, cardiovascular; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EGS, emergency general surgery; GI, gastrointestinal; HTN, hypertension; IC, incident command; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; NORA, nonoperating room anesthesia; OR, operating room; PACU, postanesthesia care unit; QI, quality improvement; SCC, surgical critical care; sitrep, situation report.

At Alert level, which many facilities in the US have already surpassed, disaster preparedness must begin in earnest and non-time–sensitive elective cases, or many cases in high risk patients, should be delayed, cancelled, and rescheduled for no sooner than 3 months in the future. Limitations on nonemergent transfers, nonoperating room anesthesia (NORA) cases, and furlough of nonessential nonclinical staff should occur. Clinic triage and telemedicine should be performed whenever able. Prioritization to develop plans for further tiers and organization of surgeons into potential call back-up pools should be performed. Additionally, in large health systems and regional collaboratives, efforts to back up community facilities from larger tertiary departments should be performed to limit transfers required due to quarantined or furloughed surgeons at these sites.

In progression to further tiers, great focus is given to the acute care surgeon’s ability to staff trauma, SCC, and EGS services, given their true vertical integration in the hospital from the emergency department, operating room, floor, and ICU. Given their flexibility, and critical care training, it will be key to support these ACS faculty with non-ACS surgeons to manage EGS and eventually, even trauma. This will allow the ACS surgeons to support expanded ICUs, operating room ICU conversion, and ECMO patients. At nontrauma centers, in the community, or with no ACS faculty, general surgeon coverage and adaptation of this plan will be paramount to cover all surgical and COVID-19 patients. At level 2, healthcare providers will begin to be furloughed, and decreased resources like blood, ventilators, and personal protective equipment (PPE) will be available. Subsequently, a 50% drawdown of all elective cases should be performed, with focus on completing necessary cardiovascular and cancer cases, but patients with high risk factors should be deferred (age > 60 years, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking history, COPD, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease). A good resource for deciding on the necessity is the Elective Surgery Acuity Scale, just released by the American College of Surgeons.21 Rearrangements of schedule and service coverage responsibility for residents, APP, and faculty should begin, and cycling of on-call teams by several days or a week should be encouraged.

Response level 1 will have accumulating provider and staff attrition due to quarantine and illness. Additionally, stocks of personal protective equipment, blood, ventilators, and other essential infrastructure will be diminished by increasing numbers of COVID-19 patients. Therefore, all nonemergent cases should be cancelled, and transfer requests managed at the requesting facility. All surgical transfers should be vetted by an ACS surgeon with situational awareness to assess its acuity, available resources and beds, and whether care may be futile. Expanded ICU beds and staffing by the ACS faculty will be required, and nonACS surgeons required to flex to cover EGS. Teams of younger ACS faculty can be deployed to cover medical ICUs if needed, and expect SCC fellows to have battlefield promotions to junior ICU attending status. ECMO should be reserved for young, noncomorbid patients, with single organ dysfunction and acceptable prognosis. Expect decreasing staff and blood availability as quarantine and social distancing affect the community. Graduated resident autonomy and chief resident-run floor services will be expected.

Finally, if the surge in patients comes as a tsunami, as it did in Italy and Wuhan, condition zero will require stretching the infrastructure and manpower beyond the breaking point. In this scenario, ACS surgeons should focus on just ICU patient care, and non-ACS surgeons cover trauma and EGS in a tiered response. Nonemergent cases should not be performed, and nonoperative modalities should be pursued if possible for all urgent disease processes. The export of urgent EGS cases may be required to other centers. Advanced triage criteria with consideration of available resources, expected increase in surge volume, patient risk factors, and principles of justice and value unfortunately must be considered for the continuation and betterment of our society. Novel ventilation strategies should be pursued whenever able, and even emergent non-COVID care may need to be triaged or suspended for certain disease processes if the system, facility, and providers are over-leveraged. At this level, COVID-19 positive healthcare workers may need to continue treating COVID-19 patients, given the extreme attrition of personnel at this level.

Principles for success

Do not lose hope. As Wuhan has taught us with social distancing, strict quarantine, and abundant testing, we can beat back this disease and mitigate its effect on our communities. In any rapidly evolving crisis, certain principles remain key to combating a constantly evolving and austere situation. Act with speed of the plan above perfection of the plan. Flexibility in the face of adversity is required, and those who are not able to deftly change strategies with new information will be battling the past and not preparing for the future. Even in this response plan, adaptation and integration of individual situations will be required. Communication with an assigned structure is vital to ensuring the entire team, service, facility, and system are working on the same page and criteria. Situation reports within each of these strata are vital to understand the situation on the ground as well as the plan for the institution. However, succinctness is required so that worried and overwhelmed providers can quickly process and implement new information and protocols. Most of all, a sense of community, purpose, and legacy is paramount to keep us mission-focused on the health of our patients and community; support and acknowledgement of our risk and sacrifice as physicians, providers…as healers, are not in vain.

Conclusions

The current COVID-19 pandemic is causing a paradigm shift for our globalized world in every sector: economic, social, cultural, and even a religious impact. The brunt of the initial surge of patients was weathered in China and has now expanded to almost every country on earth. All estimates point that the US is on track to have a similar surge of patients as did Italy, and therefore, now is the time to prepare, coordinate among key stakeholders, set up incident command, and plan for every conceivable contingency. The authors desperately hope that social distancing measures will prevail and that our tiered response plan will not be required at its highest level. However, failure to plan for these eventualities would make the outcome all the worse if or when they are needed; please use, adapt, share, and disseminate for the good of all our patients. This is the defining moment of our generation; leave a legacy worthy of remembrance. Godspeed.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Ross, Lauer, Green, Miles, Christmas, May, Matthews

Drafting of manuscript: Ross, Lauer, Green, Miles, Christmas, May, Matthews

Critical revision: Ross, Lauer, Green, Miles, Christmas, May, Matthews

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Appendix

eDoc. 1. Trauma and Emergency General Surgery Clinic Virtual Visit Process During COVID-19 Crisis

Purpose: To minimize risk to patients and staff by reducing unnecessary clinic visits as well as rapidly identifying patients who may need attention earlier to reduce hospital readmission. The goal is to allow social distancing while protecting our patients from potential issues that could require hospital admission.

-

1.

Designated acute care surgery (ACS) attending and advanced practice provider (APP) will review both the upcoming trauma and emergency general surgery (EGS) clinic appointments and review patient on electronic medical record (EMR). In addition, the attending physician will handle requests phoned into the nurse line that may be able to prevent a clinic visit.

-

2.

Patients not needing follow-up will be notified by nurse staff.

-

3.Patients deemed appropriate for virtual visit will be listed for virtual visit screening by nursing staff. (See Virtual visit screening tool)

-

a.If patient has virtual access, then appointment scheduled.

-

b.ACS attending or APP will call patient using technology device deemed appropriate from screening tool.

-

i.All x-rays and labs will be determined prior to call and patient to get labs and x-rays performed at closest site.

-

ii.Medications and supplies and therapies will be ordered as outpatient and an EMR note will be completed.

-

i.

-

a.

-

4.If patient deemed a physical appointment presence is needed (either from screening or from virtual appointment):

-

i.The patient and ONLY 1 family member are allowed to attend clinic appointment.

-

ii.COVID-19 screening will be done at triage front desk. If screening is positive, they will be asked to get testing for COVID-19.

-

iii.If the patient still needs to be seen that day due to emergency, a mask will be worn by family member and patient and a dedicated room will be used.

-

iv.Only 1 nurse and 1 physician/APP will examine patient using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and N95 mask.

-

v.After completion, PPE will be discarded in red bag and room wiped down per protocol.

-

i.

-

5.

If patient calls into clinic number with a problem, he or she will be screened by nurse and referred to dedicated ACS clinic attending to be handled immediately via virtual device or phone call to prevent need for physical appointment.

Notes:

-

1.

If a patient and/or family member is suspected of having COVID-19 they are sent for testing.

-

2.

This is a dynamic process and process may change. The goal is to protect patients and staff by allowing safe social distancing while identifying complex issues early so they may be handled.

-

3.

We will attempt to use virtual visit capture via “whatsapp” or SKYPE IF patients have access. If not, we will use dedicated I-phone or Samsung video or pictures to evaluate patients and their wounds or concerns.

-

4.

If a patient has staples or sutures, ask them to use the primary care physician. If not available, they can attend clinic appointment and be screened for COVID-19 infections.

-

5.

If physical patient presence is necessary, all trauma and EGS patients will be seen.

-

6.

All medications, dressing materials, and ostomy supplies will attempt to be handled as a virtual visit and home health scheduled appointments.

eDocument 2. Trauma and Emergency General Surgery Clinic Screening Tool for Virtual Evaluation (COVID-19 Crisis)

-

1.Infectious Disease Risk Screening Questions (If + then referred for testing per admitting hospital Protocol)

-

2.Do you have access to a smart phone with video capability?

-

a.If so, which type: Samsung: ____________ I-Phone: ______________ Other: ____________

-

a.

-

3.

Do you have access to computer with video camera? Yes______ No_______

-

4.

Are you able to download a free app such as “WhatsAPP” or SKYPE or TEAMS to assist in videoconferencing? Yes _________ No_________

(We will provide a free app access, if needed!)

-

5.Functional Status:

-

a.Pain level: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10. Medication needs: __________________

-

b.Ambulation: Normal ________________ Limitations__________________

-

c.Wounds/Incisions: 1. ___________________ 2. _________________________ 3. ______________________

-

i.Staples/Sutures:__________________

-

ii.Clean and dry or drainage?____________

-

iii.Amount of drainage:_______________

-

i.

-

d.Drains: None: ________________ Yes: 1. _________ 2. ___________Amount(s)___________ ___________

-

a.

-

6.

Hygiene: Bathing: Yes________ NO________ if NO, were you told not to bathe? _______

-

7.

PO Intake: Percentage of daily meals: 25%______ 50%______ 75%_____ 100%______

-

8.

Fluid intake______________________________

-

9.

Bowel Function: constipation___________ Normal___________ Diarrhea___________

-

10.

Urination: Normal_______ Abnormal_________

-

11.Other issues that patient may have to be addressed:

-

a.____________________________________________________

-

b.____________________________________________________

-

c._____________________________________________________

-

d._____________________________________________________

-

e._____________________________________________________

-

a.

eDocument 3. Virtual / Telemedicine Acute Care Surgery Clinic History and Virtual Exam Template

History of present illness:

Perform Infectious risk screen. If positive, direct patient to Covid-19 testing center

Discuss and document any presenting symptoms patient may have

Review the previously completed screening tool assessing specific organ issues, diet, breathing, drains, and potential infection

Vitals:

Assess pulse by coaching the patient on how to take their own pulse

Assess respiratory rate and work of breathing

Assess whether patient has fever. If so, document temperature

Exam:

Assess appearance of the individual; mildly ill, moderately, toxic

Note presence of signs of infection

Ask patient to show respiratory effort and use of accessory muscles. Have them take a few deep breaths

Have patient show areas of abdomen, incisions, or previously trauma or surgery. Document areas separately with appearance, swelling, or drainage.

Have patient point to areas of pain and have them describe the pain: site, type, and level

Ask patient to show anything else that they feel is important for your assessment

Have patient palpate the area of concern and document ability to do so

Evaluate any incision sites, redness, swelling, drainage and document

Evaluate time frame of staples or stitches and document appearance and when they should be removed

Evaluate drains and document amounts and appearances

Assessment:

Reconfirm with patient the reasons for “distancing” and supportive therapies as needed

Reiterate with patient the limitations that clinic has using a virtual visit

Discuss with patient any issues determined based on virtual exam

Discuss any labs or radiographs or consultations needed

Recommend any emergency evaluations if issues are noted

Discuss with patient timing of staples, stitches, or drain removal

Discuss with patient the plan, management, and any prescriptions needed

Discuss with patient and/or caregiver timing of next visit

References

- 1.Control C.F.D. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). CDC. Situation Summary Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html Available at: Published 2020. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- 2.COVID-19 Map Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Availablae at:

- 3.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. Feb 24 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai M.C., Arnold J.L., Chuang C.C. Implementation of the Hospital Emergency Incident Command System during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) at a hospital in Taiwan, ROC. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen X., Li Y. Anesthesia procedure of emergency operation for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Surg Infect. 2020;21:299. doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ti L.K., Ang L.S., Foong T.W., Ng B.S.W. What we do when a COVID-19 patient needs an operation: operating room preparation and guidance. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grasselli G., Pesenti A., Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020 Mar 13 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020 Mar 13;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covid-19 National Emergency Response Center E, Case Management Team KCfDC, Prevention Contact transmission of COVID-19 in South Korea: Novel investigation techniques for tracing contacts. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11:60–63. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.1.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neyman G., Irvin C.B. A single ventilator for multiple simulated patients to meet disaster surge. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1246–1249. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chacko S., Randolph R., Morsch G. Disaster medicine: public health preparedness for natural disasters. FP Essent. 2019;487:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlosser K.R., Creedon J.K., Michelson K.A., Michelson C.D. Lessons from the 2013 Boston Marathon: Incorporating residents into institutional emergency plans. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niska R.W., Burt C.W. Bioterrorism and mass casualty preparedness in hospitals: United States, 2003. Adv Data. 2005;(364):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin S.D., Bush A.C., Lynch J.A. A national survey of terrorism preparedness training among pediatric, family practice, and emergency medicine programs. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e620–e626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White D.B., Katz M.H., Luce J.M., Lo B. Who should receive life support during a public health emergency? Using ethical principles to improve allocation decisions. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:132–138. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monella L.M. Coronavirus: Italy doctors 'forced to prioritise ICU care for patients with best chance of survival'. Euronews. Published March 13, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/12/coronavirus-italy-doctors-forced-to-prioritise-icu-care-for-patients-with-best-chance-of-s Available at:

- 18.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 11 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nittari G., Khuman R., Baldoni S. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J E Health. 2020 Feb 12 doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0158. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.North F., Varkey P., Bartel G.A. Can an office practice telephonic response meet the needs of a pandemic? Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:1012–1016. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.COVID-19: Guidance for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures [press release]. March 17, 2020. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage. Accessed April 17, 2020.